1. Introduction

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is a debilitating condition that affects between 6 and 25% of women worldwide, depending on the inclusion criteria [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. CPP is linked to poor health-related quality of life and decreased work efficiency [

6]. Indeed, a recent systematic review estimated that the yearly cost of CPP is 2.8 billion dollars [

7]. CPP accounts for nearly 10% of gynecology consultation, 12% hysterectomies and more than 40% of diagnostic laparoscopies [

8,

9]. However, the WHO defined it as “a neglected reproductive health morbidity” since, despite its significance, healthcare planning ignored it and failed in resource allocation due to a lack of primary epidemiological data [

6]. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the ReVITAlize initiative define CPP as the presence of non-cyclic pelvic pain which lasts for 6 months or longer, unrelated to pregnancy, that can be exacerbated by sexual intercourse or menstrual cycles and often associated with negative cognitive, behavioral, sexual and emotional consequences [

10,

11]. In addition to this, studies reveal a frequently delay in the diagnosis with up to 50% of women without one even after many years of follow-up [

12,

13,

14].

The pain is related to the pelvis and both patients and clinicians localize the pain as perceived there. The experience of pain is the result of activities within the central nervous systems (CNS) [

15], therefore, women with CPP have changes in brain morphology or function similar to the ones with other chronic pain conditions [

16]. These changes activate specific brain regions and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adnexal axis linked to an increased psychologic distress [

17].

Central sensitization is important for the perpetuation of chronic pain syndromes since it explains allodynia (feeling of pain in response to innocuous stimuli) and hyperalgesia (feeling a heightened response to painful stimuli) [

17].

There are differential diagnosis for CPP, ACOG recommends to organize the possibilities into visceral, neuromusculoskeletal and psychosocial contributors (

Table 1), however it is pivotal to maintain awareness of the multifactorial etiology which requires an interdisciplinary model of care [

18].

Endometriosis is a chronic disease which causes CPP in up to 80% of cases [

19,

20]. Endometriosis symptoms are commonly dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia and perimenstrual lower abdominal pain; however patients with endometriosis may refer dyschezia, dysuria and even urinary frequency [

20,

21]. Indeed, symptoms have little correlation to the extent of endometriosis, therefore in a woman with CPP, even if endometriosis is found it is always mandatory to consider other causes. After endometriosis is suspected, the confirmation is the laparoscopic visualization with positive biopsy [

20]; however, the latest guidelines of the European Society for Reproductive Medicine (EHSRE) [

22] highlighted also the role of ultrasound evaluation and empirical treatment as first step in the management of patients with endometriosis.

Interstitial cystitis / bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) is a chronic condition characterized by an unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure or discomfort) perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than six weeks duration in the absence of any other identifiable pathology (such as urinary tract infections, bladder carcinoma or cystitis) [

23].

It was thought that this was a rare condition, however now it is known that the prevalence is between 2.7% and 6.5% [

24] of all women.

According to the results of the Interstitial Cystitis Data Base (ICBD) Study sponsored by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK), 93,6% of classic interstitial cystitis patients report various degrees of pain [

25], mainly located in the lower abdomen, in the lower back, in the vaginal area and in the rectum. The other most frequent symptom is urgency (80.4% of patients).

According to European Association of Urology [

26] and the European Society for the Study of Interstitial Cystitis (ESSIC) [

26] the diagnosis of IC/PBS is based on clinical symptoms. Since it is a clinical diagnosis, it is important to exclude confusable diseases as the cause of the pain, such as carcinoma of the bladder, infections, radiation, chemotherapy. The cystoscopy with hydrodistension and biopsies can document positive signs of PBS, making the diagnosis more probable, especially in patients in which the presence of Hunner’s lesions is more frequent (patients older then 50 years old) or who fail first line treatment [

27]. According to cystoscopy findings, sub-phenotypes of IC/PBS were found. Patients who are Hunner’s lesions negative and non-low anesthetic bladder capacity (> 400 ml) have a non-bladder centritic phenotypes which is more commonly associated with systemic pain disorders [

28].

The purpose of this systematic review was to estimate the prevalence of the coexistence of endometriosis and IC/PBS in women with CPP. Previous papers have suggested a strong relationship between IC/PBS and endometriosis, also named the evil twins. However, update only a little data is available, mainly in case reports and small series. Consequently, this systematic review aimed to estimate the prevalence of the coexistence of endometriosis and IC/PBS in women with CPP.

2. Materials and Methods

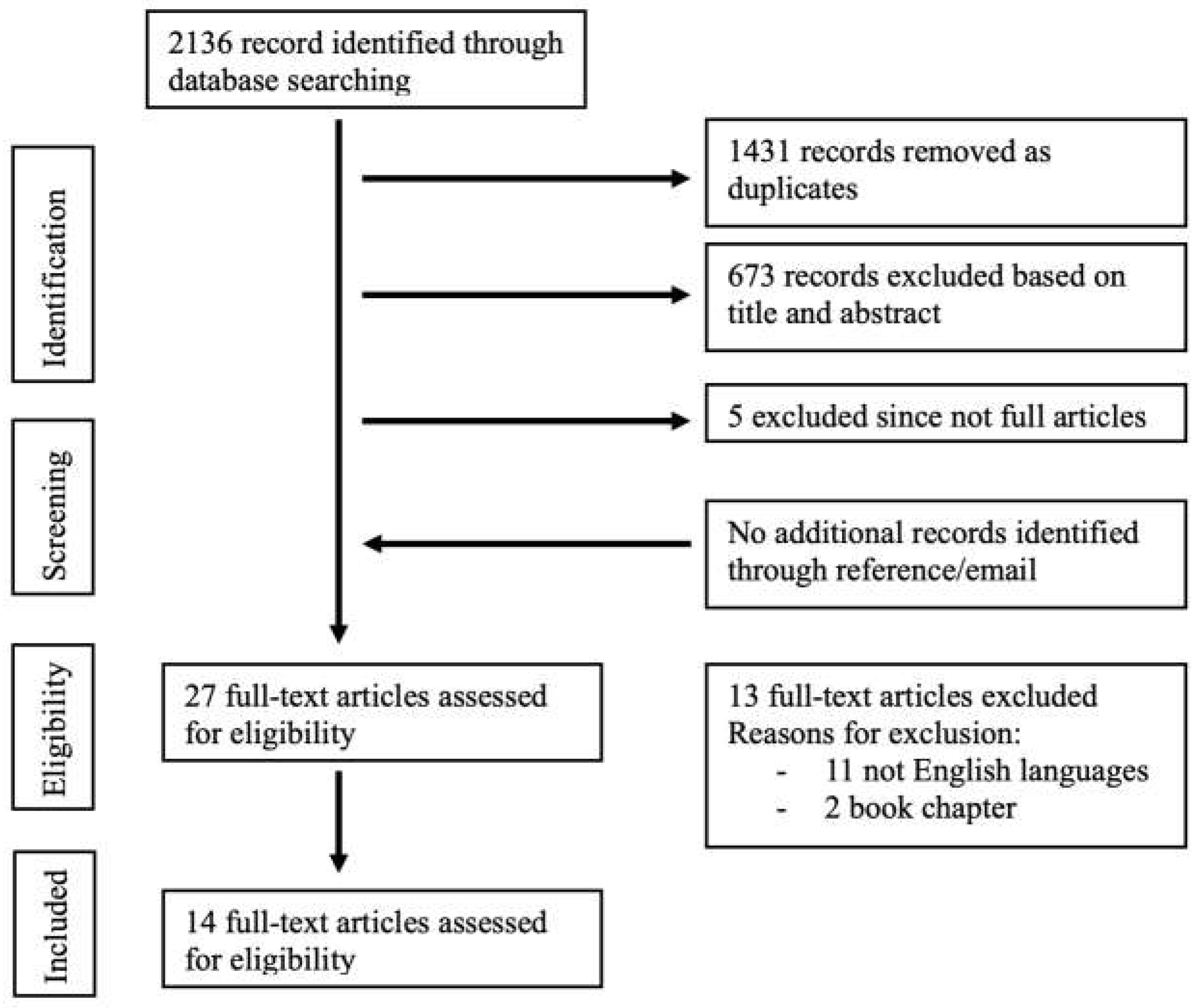

We performed a systematic search of literature indexed on PubMed, Scopus, ISI Web of Science, Cochrane (from the start to 04th of March 2024—start date of search), using EndNote x8 (Clarivate Analytics). We used a combination of keywords and text words represented by “painful bladder syndrome” AND “endometriosis”, “interstitial cystitis” AND “endometriosis”, “bladder pain syndrome” AND “endometriosis”. A complete search strategy is provided in

Figure 1. Four reviewers (AI, VC, FM, MB) independently screened titles and abstracts of the records that were retrieved through the database searches. No article type restrictions were applied. We considered only articles in the English language. We also performed a manual search to include additional relevant articles, using the reference lists of key articles. Full texts of records recommended by at least one reviewer were screened independently by the same two reviewers and assessed for inclusion in the systematic review. Disagreements between reviewers were solved by consensus. Data selection and extraction were conducted in accordance with PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study type) using a piloted form specifically designed for capturing information on study and characteristics. Data were extracted independently by two authors to ensure accuracy and consistency.

3. Results

3.1. Sudy Assessment

The electronic database search provided a total of 2136 results. After duplicate exclusion, there were 705 citations left. Of them, 673 were not relevant to the review based on title and abstract screening and 5 studies were excluded since were not full articles. Twenty-seven studies were considered for full-text assessment, of which 13 were excluded for the following reasons: 2 book chapters and 11 papers were excluded for being in languages other than English. No paper was added through reference list searching. Overall, 14 studies met the inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the review process. The papers included mostly retrospective and prospective studies and 1 cohort study; they were all published after 2002 with the most recent in 2016 [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42].

3.2. Main Findings

This review includes a total of 747 patients, the characteristics of the studies are listed in

Table 2.

3.2.1. Prevalence

The incidence of the coexistence between IC/PBS and endometriosis depended on the reference population.

3.2.2. The Prevalence of IC/PBS in Women with Endometriosis

Wu et al. [

42] published a population-based study of patients with endometriosis and random controls. During a follow-up of three years, IC/BPS was diagnosed in 0,20% of patients with endometriosis and 0,05% of patients without endometriosis. The hazard risk (HR) for the development of IC/PBS in patients with endometriosis was 3,74 after adjusting for comorbid associations (diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease, obesity, hyperlipidemia, chronic pelvic pain, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, depression, panic disorder, migraine, sicca syndrome, allergy, asthma and overactive bladder). Although a small number of patients developed IC/PBS during follow-up (30 subjects with a sample size of 36.764 patients), this study suggests that endometriosis is associated with BPS/IC. Indeed, a possible explanation for this small number is the relatively low follow-up time and the identification of the diagnoses through ICD-9-CM codes, which may exclude patients who need to be classified correctly.

Smorgick et al. [

40] retrospectively evaluated young women with surgical diagnosis of endometriosis prior than 21 years old for the presence of other comorbid pain syndromes. Most patients had I or II stage endometriosis (84%). IC/PBS was found in 16% patients with endometriosis. As in the previous cited one, also in this study the follow up period was short (25 months on average) and this can justify the low number of patients with IC/PBS who were identified.

3.2.3. The Prevalence of IC/PBS and Endometriosis in Women with CPP

Most studies however focused on the diagnosis of IC/PBS in women with CPP since it has been underestimated for many years. In the studies included in this review, data about the coexistence of IC/PBS and endometriosis in women with CPP were present.

Chung et al. [

31] were among the first to verify the association between IC/PBS and endometriosis. They performed a retrospective study in 2002, including patients with CPP who underwent laparoscopy, cystoscopy and hydrodistensions. Interestingly, of the 60 patients included, 58 were diagnosed with IC/BPS, and 56 had received a diagnosis of endometriosis; of them, 48 had biopsy-confirmed lesions at laparoscopy, while 8 had negative laparoscopy. In the group of patients with IC/BPS, 47 (81%) had a history of biopsy-proven endometriosis, while 7 had a history of endometriosis with negative biopsies at diagnostic laparoscopy. In the group of patients with a history of endometriosis, 54 (96,6%) had a diagnosis of IC made by cystoscopy or hydrodistensions. This study highlights the high prevalence of both these conditions in patients suffering from CPP. Besides, the presence of IC/PBS in women with a diagnosis of endometriosis not confirmed by diagnostic laparoscopy may mean that in those patients the reason for CPP was IC/PBS and not endometriosis. Interestingly, this study also included patients without symptoms of IC/PBS, but many of them were diagnosed with IC/PBS (13, 22,5% of patients with IC/PBS). Therefore, the authors suggest that cystoscopy should be routinely performed in order to avoid missing the diagnosis of IC/PBS in CPP patients.

In 2005, the same authors [

30] prospectively evaluated the presence of both endometriosis and IC/PBS in patients with CPP through diagnostic laparoscopy, cystoscopy and the potassium sensitivity test (PTS). Of the 178 patients with CPP evaluated, 115 (65%) had both IC and endometriosis. However, they included patients with CPP and bladder base/anterior vaginal wall and uterine tenderness with or without voiding symptoms. Therefore, the prevalence of CPP in this study could be overestimated more than that of patients with CPP.

In a prospective study, Clemons et al. [

32] evaluated the presence of IC/PBS in patients scheduled for a diagnostic laparoscopy for CPP. They made the diagnosis of IC/PBS with a combination of urgency, frequency or nocturia and positive cystoscopic findings. In their sample size of 45 women, 17 (38%) had IC/PBS, and 21 (48%) had endometriosis; however, seven patients with endometriosis were diagnosed with IC/PBS (16% of women with CPP). If we also include patients with adhesions and IC/PBS (4 patients), the percentage rises to 24%.

In this study the presence of IC/PBS was not associated with laparoscopic findings, this may highlight the need to perform cystoscopy regardless of the presence of endometriosis or adhesion. However, according to all the new diagnostic criteria for IC/PBS, it is not mandatory to perform cystoscopy to make the diagnosis. Secondly, all women with endometriosis had stage I or II (only one woman had bladder endometriosis). Therefore, the coexistence of these IC/PBS and endometriosis is also found in the early stage of the disease.

Also Cheng et al. [

29] evaluated the prevalence of IC/PBS in patients with CPP. The percentage of IC/PBS was different depending on the diagnostic criteria which were used (IC as the presence of CPP with at least one urinary symptom and the presence of glomerulations at cystoscopy; PBS as per the ESSIC [

26] definition which is a clinical one without the confirmation by cystoscopy). In their population, 50% of those with endometriosis had BPS and 60% of women with BPS had endometriosis. Interestingly, in this study a high prevalence of urinary symptoms was found in women with dysmenorrhea (94%).

Rackow et al. [

38] focused on young women ages 13 to 25 with CPP. They performed diagnostic laparoscopy and cystoscopy in 28 patients referred for CPP.

Eleven patients (39%) were diagnosed with IC and 18 (64%) with endometriosis. The coexistence of these two conditions was found in 7 (25%) of cases. In these patients, there was no association between some urinary symptoms (urgency or nocturia) and IC, and this is probably linked to the natural history of the disease and the age of the patients included. In this study, the routine evaluation of symptoms did not differ between IC and endometriosis, suggesting the need to evaluate both the pelvis and bladder constantly; however, a possible explanation for this is that the authors did not use validated questionnaires since the retrospective nature of this study.

Paulson et al. performed two studies, since the latter were preospective and with similar inclusion criteria [

36,

37], we can not exclude that some patients were included in both of them. Therefore, we will focus on the results from the last one.

They evaluated 284 patients with CPP who underwent cystoscopy or laparoscopy. Of them, 172 (61%) had both endometriosis and interstitial cystitis.

Finally, Stanford et al. [

39] screened women with CPP through diagnostic laparoscopy and PST. Of 64 women included, 48 (69%) had positive PST, 18 (28%) biopsy-proven endometriosis and 41 (64%) adhesions. 42% (27 patients) had positive PST and a diagnosis of endometriosis or adhesions or both. The authors did not specify the prevalence of a positive PST in women with only endometriosis (excluding the ones with adhesions).

3.2.4. The Prevalence of Endometriosis in Women with IC/PBS

Overholt et al. [

35] evaluated as reference population women with non-bladder centritic IC/PBS, through the use of a registry. The patients were divided into women with a known history of endometriosis and women without. Of all women with IC/PBS, 19% had co-occuring endometriosis. Compared to patients without coexistence of endometriosis, patients with both of them had higher prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), CPP, fibromyalgia and vulvodynia.

Also Warren et al. [

41] through a case-control study found that the prevalence of endometriosis was higher in women with IC/PBS than controls (20% vs 6%) with an odds ratio of 3.6. This again was true also for migraine, IBS and and fibromyalgia.

Both these studies suggest that some patients with IC/PBS have a more systemic syndrome not confined to the bladder.

3.2.5. Burden of Coexistence between Endometriosis and IC/PBS

As we have seen, the coexistence between endometriosis and IC/PBS is frequent regardless of the population studied. For this reason, over the years, it is possible that many useless surgeries have been performed in patients with CPP for the differential diagnosis. Ingber et al. [

33] pointed this out in their study, which evaluated the rate of pelvis surgeries patients with IC/PBS perform.

They performed a retrospective cross-sectional case-control study included 406 women with established diagnosis of IC/PBS from clinical databases and 5000 randomly matched controls. This was part of a larger study evaluating risk factors, natural history and comorbidities of IC [

43]. Patients with IC/PBS reported more frequently all types of pelvic surgery included than control. In particular, they more often performed hysterectomy, bladder suspensions, laparoscopic pelvic surgeries, dilatation and curettage (D&C). Interestingly, some surgeries were done before or the same years as the diagnosis of IC/PBS was made (68,4% of all hysterectomies before and 10,5% the same years; 25% of all bladder suspensions before and 39,3% the same year); while some was mostly made after the diagnosis of IC/PBS (60% of cystocele repairs and 66% of rectocele repairs). In besides, in this study women with IC/PBS were more commonly diagnosed with endometriosis and fibroids than controls.

Lentz et al. [

34] focused retrospectively on women with intractable IC who were referred to a tertiary urology centre. Twenty-three of them had symptoms that fluctuated during menstrual cycles with premenstrual exacerbation of pain. Of these, 18 underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, and in 10 of them, a diagnosis of endometriosis was made. Fifteen women (out of the 18 who underwent surgery) were treated with hormonal therapy, 9 with a GnRH analogue and 6 with cyclic oral contraceptive pills (OCPs). Thirteen (87%) of women who were treated with hormonal therapy had an improvement in symptoms; this accounts for all women with a coexistence between endometriosis and IC/PBS except for two women.

This study underlines the role of excluding other pain disorders in women with intractable IC. This is pivotal since we know that endometriosis is a chronic condition which can progress over time. Therefore, a punctual diagnosis is mandatory to prevent higher stages of disease.

3.2.5. Clinical Evaluation and Diagnosis

Pauslon et al. [

37] focused on the role of anterior vaginal wall tenderness (AVWT) as a diagnostic marker for the coexistence between endometriosis and IC/PBS. AVWT was present in 96% patients with only IC, and in 39% of patients with only endometriosis. However, when evaluated in patients with both of them, the percentage raised to 94%. This underlines the use of physical examination prior to invasive tests to rule out the diagnosis of endometriosis and IC/PBS.

4. Discussion

Patients with CPP can face difficulties in the evaluation and management of their pain. Since years endometriosis is considered the leading cause of CPP; however nowadays we know that not all women with endometriosis have pain and that, even in the presence of endometriosis, gynecologists need to have high suspicious for other disease [

19,

20,

44]. In recent years, the possible coexistence between endometriosis and IC/PBS raised awareness, thus leading to different studies. This comes from the increasingly evident need to find an answer to chronic pelvic pain for women who live with psychological distress and who underwent surgeries without beneficial effects. Indeed, few studies [

33,

45] demonstrated that women with IC/PBS undergo more frequently than healthy controls pelvic surgery. Similarly, Gretchen et al. [

34] treated with success women with IC/PBS who were refractory to all standard therapy for IC/PBS with hormonal therapy, which is commonly prescribed for endometriosis. Notably, in this study, the mean duration of symptoms was 9.5 years (range 1-26).

This justifies the term “evil twin syndrome” which was coined by Chung et al. [

31] to refer to the coexistence between endometriosis and IC/PBS (

Figure 3).

Studies from the literature suggest that in women with CPP the coexistence between endometriosis and IC/PBS is frequent.

Table 3 summarizes the results from the studies, the prevalence ranges between 15,5-78,3%.

One of the central limits in evaluating the prevalence of this coexistence is the need for more solid data about the prevalence of endometriosis and IC/PBS taken alone.

Since we lack strict guidelines or diagnostic procedures for IC/PBS, the prevalence in women with CPP varies much across countries, and many studies probably underestimate it [

46]. In the same way, the exact prevalence of endometriosis is not known; however, nowadays, we see that it is much more common than what was thought before, even if it remains underdiagnosed and with an essential diagnostic delay [

47]. In besides, the laparoscopic visualitation of endometriosis may be influenced by the expertise of the surgeon, and the presence of active lesions can be hidden by long-term hormonal therapy. Finally, difference between studies may be linked to the diagnostic criteria they used for the diagnosis of IC/PBS and above all to the selection bias. It is reasonable that urongynecological center selected more women with IC/PBS than center specialized in endometriosis. This is supported by the fact that the prevalences are similar when studies are performed by the same authors. Unfortunately, few studies evaluated the diagnosis of IC/PBS after this term was proposed by ESSIC in 2008 [

26].

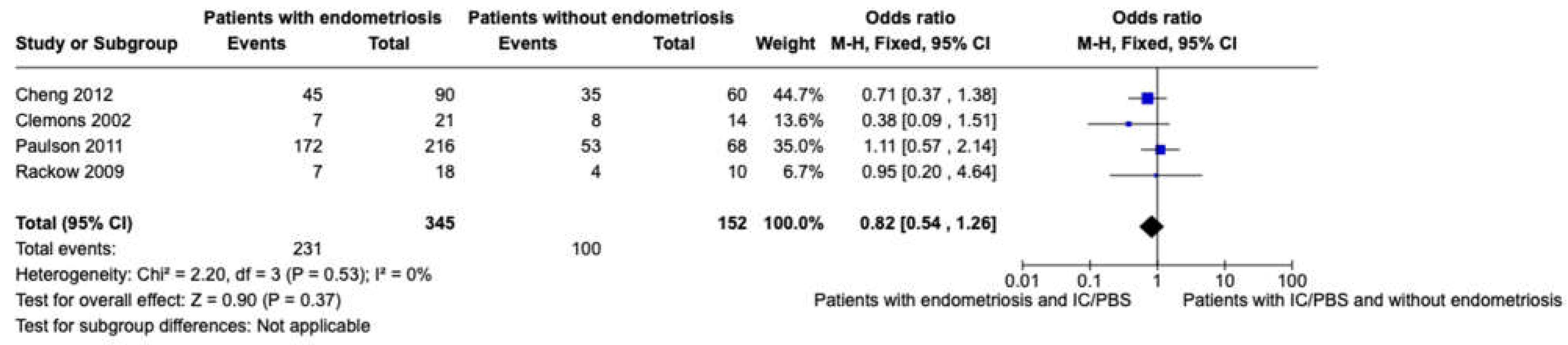

After excluding studies where there was not a distinction between patients with endometriosis and adhesions [

39] and where the absence of both of them was not evaluated [

30,

31], we performed a meta-analysis of women with CPP with or without endometriosis considering the presence of IC/PBS as the event, including only studies where women with CPP were evaluated with laparoscopy and concurrent cystoscopy [

29,

32,

37,

38] (

Figure 2).

An interesting point is that IC/PBS prevalence in the general population is lower (2-17.3%) [

48] than we reported for patients with coexistent endometriosis; and this highlights the shared pathway for the genesis of chronic pelvic pain syndromes.

Hysterectomy is the second most commonly frequently performed surgery after caesarean delivery in women of reproductive age. As we reported, CPP is the reason for hysterectomy in up to 12% of women [

8,

9]. However, nearly 20-25% [

49,

50] of patients will undergo surgery without relief in pain; therefore, hysterectomy should be considered only after the exclusion of other gynaecological or not diseases. As for endometriosis, IC can also have a significant delay in the diagnosis. Indeed, Driscoll et al. [

51] found that patients are symptomatic for IC for a median of 5 years before being diagnosed; patients present more frequently with just one symptom (in 89% of cases) and progressively develop the full spectrum of symptoms. This is consistent with the higher rate of surgery in women with IC/PBS. Besides, in women with persistent pain after a hysterectomy, IC/PBS is diagnosed with high rates and can be resolved with the correct treatment [

52]. However, even if the causative role of surgery in the development of IC/PBS can not be excluded at all since pelvic surgeries can harm the physiology of the bladder [

33], it is more plausible that many women with endometriosis refractory to medical treatment who are counselled correctly about surgical treatment with hysterectomy, already have IC/PBS. This means that even if the diagnosis of IC/PBS is of exclusion, the presence of endometriosis does not exclude the presence of IC/PBS. However, the fact that hysterectomy may not cure the symptoms or the disease is also probably dependent on the radicality of the surgery or the centralisation of pain, and European guidelines suggest to counsel women that hysterectomy may not be a definitive treatment [

22].

Women with symptoms of IC/PBS can report less the presence also of dysmenorrhea or dyspareunia since they do not link the symptoms together; in this point of view, the use of validated questionnaire may play a role in screening for IC/PBS. Concerning this, a multidisciplinary approach may help in overcoming the diagnostic limits of these two conditions, and in treating both of them correctly.

The first-line approach for endometriosis is medical therapy with a combined contraceptive pill or progestin therapy [

22]. When treatment fails, the second-line approach is surgery. The radicality of surgery depends on the desire for childbearing; when a woman has ended her childbearing desire, the choice is for a hysterectomy. The recurrence of endometriosis after hysterectomy is extremely low and depends on the radicality of the surgery and on the concomitant bilateral ovariectomy [

53,

54].

First-line treatment of IC/PBS is with oral drugs (pentosan polysilfate sodium, hydroxyzine, amitriptyline, pregabalin). Several intravescical therapies can be used, such as endovescical hyaluronic acid/chondroitin sulfate, in combination or not with oral drugs [

55].

5. Conclusions

The diagnosis of both endometriosis and IC/PBS requires specific expertise, so women should be referred to a center with a multidisciplinary approach. Additionally, due to the consistent burden of IC/PBS in women with endometriosis, it should be mandatory to screen for urinary symptoms even if the presence of endometriosis is confirmed. If the suspected presence of IC/PBS is indicated, a specialized doctor must take care of the patient.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F., P.P and A.I.; methodology, M.F. and A.I.; formal analysis, M.F.; investigation, V.C., M.B., A.C., M.F., S.P.; resources, V.C., M.B., A.C., M.F., S.P.; data curation, V.C., M.B., A.C., M.F., S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.I.; writing—review and editing, A.I., M.F., V.C., M.B., A.C., M.F., S.P.; visualization, M.F..; supervision, M.F. and P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Analyzed or generated during the study can be requested to corresponding authot upon reasonable rewquest.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- García-Pérez, H.; Harlow, S.D.; Erdmann, C.A.; Denman, C. Pelvic Pain and Associated Characteristics among Women in Northern Mexico. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2010, 36, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, V.M.; Zondervan, K.T. Chronic Pelvic Pain in New Zealand: Prevalence, Pain Severity, Diagnoses and Use of the Health Services. Aust N Z J Public Health 2004, 28, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahangari, A. Prevalence of Chronic Pelvic Pain among Women: An Updated Review. Pain Physician 2014, 17, E141–E147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Yudkin, P.L.; Vessey, M.P.; Jenkinson, C.P.; Dawes, M.G.; Barlow, D.H.; Kennedy, S.H. Chronic Pelvic Pain in the Community—Symptoms, Investigations, and Diagnoses. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001, 184, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayorinde, A.A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Druce, K.L.; Jones, G.T.; Macfarlane, G.J. Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women of Reproductive and Post-reproductive Age: A Population-based Study. European Journal of Pain 2017, 21, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latthe, P.; Latthe, M.; Say, L.; Gülmezoglu, M.; Khan, K.S. WHO Systematic Review of Prevalence of Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Neglected Reproductive Health Morbidity. BMC Public Health 2006, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Le, A.-L.; Goddard, Y.; James, D.; Thavorn, K.; Payne, M.; Chen, I. A Systematic Review of the Cost of Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2022, 44, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.C. A Profile of Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1990, 33, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Howard, F.M. The Role of Laparoscopy in Chronic Pelvic Pain: Promise and Pitfalls. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1993, 48, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, M.; Baranowski, A.P.; Elneil, S.; Engeler, D.; Hughes, J.; Messelink, E.J.; Oberpenning, F.; de C Williams, A.C. EAU Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain. Eur Urol 2010, 57, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ReVitalize. Gynecology Data Definitions.

- Grace, V.M.; Zondervan, K.T. Chronic Pelvic Pain in New Zealand: Prevalence, Pain Severity, Diagnoses and Use of the Health Services. Aust N Z J Public Health 2004, 28, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, V.M. Problems of Communication, Diagnosis, and Treatment Experienced by Women Using the New Zealand Health Services for Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Quantitative Analysis. Health Care Women Int 1995, 16, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Yudkin, P.L.; Vessey, M.P.; Dawes, M.G.; Barlow, D.H.; Kennedy, S.H. Patterns of Diagnosis and Referral in Women Consulting for Chronic Pelvic Pain in UK Primary Care. BJOG 1999, 106, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, I.; Mantyh, P.W. The Cerebral Signature for Pain Perception and Its Modulation. Neuron 2007, 55, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, S.; Hermans, L.; Willems, T.; Roussel, N.; Meeus, M. Literature Review Central Sensitization In Urogynecological Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Systematic Literature Review.

- Brawn, J.; Morotti, M.; Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Vincent, K. Central Changes Associated with Chronic Pelvic Pain and Endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update 2014, 20, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetric and Gynecology Practice Bulletin Num 218: Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists Chronic Pelvic Pain; 2020.

- Carter, J.E. Combined Hysteroscopic and Laparoscopic Findings in Patients with Chronic Pelvic Pain. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1994, 2, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins--Gynecology ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 11: Medical Management of Endometriosis. Obstetrics and gynecology 1999, 94, 1–14.

- Sircus, S.I.; Sant, G.R.; Ucci, A.A. Bladder Detrusor Endometriosis Mimicking Interstitial Cystitis. Urology 1988, 32, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESHRE Endometriosis Guidelines; 2022.

- Hanno, P.M.; Erickson, D.; Moldwin, R.; Faraday, M.M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome: AUA Guideline Amendment. Journal of Urology 2015, 193, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkle, K.S.; Berry, S.H.; Elliott, M.N.; Hilton, L.; Suttorp, M.J.; Clauw, D.J.; Clemens, J.Q. Comparison of an Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome Clinical Cohort with Symptomatic Community Women from the RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology Study. J Urol 2012, 187, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, L.J.; Landis, J.R.; Erickson, D.R.; Nyberg, L.M. The Interstitial Cystitis Data Base Study: Concepts and Preliminary Baseline Descriptive Statistics. Urology 1997, 49, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Merwe, J.P.; Nordling, J.; Bouchelouche, P.; Bouchelouche, K.; Cervigni, M.; Daha, L.K.; Elneil, S.; Fall, M.; Hohlbrugger, G.; Irwin, P.; et al. Diagnostic Criteria, Classification, and Nomenclature for Painful Bladder Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis: An ESSIC Proposal. Eur Urol 2008, 53, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, J.Q.; Erickson, D.R.; Varela, N.P.; Lai, H.H. Diagnosis and Treatment of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. Journal of Urology 2022, 208, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.J.; Zambon, J.; Andersson, K.-E.; Langefeld, C.D.; Matthews, C.A.; Badlani, G.; Bowman, H.; Evans, R.J. Bladder Capacity Is a Biomarker for a Bladder Centric versus Systemic Manifestation in Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. J Urol 2017, 198, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Rosamilia, A.; Healey, M. Diagnosis of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Prospective Observational Study. Int Urogynecol J 2012, 23, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, M.K.; Chung, R.P.; Gordon, D. Interstitial Cystitis and Endometriosis in Patients With Chronic Pelvic Pain: The “Evil Twins” Syndrome; 2005.

- Chung, M.K.; Chung, R.R.; Gordon, D.; Jennings, C. The Evil Twins of Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: Endometriosis and Interstitial Cystitis. JSLS 2002, 6, 311–314. [Google Scholar]

- Clemons, J.L.; Arya, L.A.; Myers, D.L. Diagnosing Interstitial Cystitis in Women With Chronic Pelvic Pain; 2002.

- Ingber, M.S.; Peters, K.M.; Killinger, K.A.; Carrico, D.J.; Ibrahim, I.A.; Diokno, A.C. Dilemmas in Diagnosing Pelvic Pain: Multiple Pelvic Surgeries Common in Women with Interstitial Cystitis. Int Urogynecol J 2008, 19, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, G.M.; Bavendam, T.; Stenchever, M.A.; Miller, J.L.; Smalldridge, J. Hormonal Manipulation in Women with Chronic, Cyclic Irritable Bladder Symptoms and Pelvic Pain. In Proceedings of the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology; Mosby Inc., 2002; Vol. 186, pp. 1268–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Overholt, T.L.; Evans, R.J.; Lessey, B.A.; Matthews, C.A.; Hines, K.N.; Badlani, G.; Walker, S.J. Non-Bladder Centric Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome Phenotype Is Significantly Associated with Co-Occurring Endometriosis. Can J Urol 2020, 27, 10257–10262. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson, J.D.; Delgado, M. The Relationship Between Interstitial Cystitis and Endometriosis in Patients With Chronic Pelvic Pain; 2007.

- Paulson, J.D.; Paulson, J.N. Anterior Vaginal Wall Tenderness (AVWT) as a Physical Symptom in Chronic Pelvic Pain. Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons 2011, 15, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rackow, B.W.; Novi, J.M.; Arya, L.A.; Pfeifer, S.M. Interstitial Cystitis Is an Etiology of Chronic Pelvic Pain in Young Women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2009, 22, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, E.J.; Koziol, J.; Feng, A. The Prevalence of Interstitial Cystitis, Endometriosis, Adhesions, and Vulvar Pain in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2005, 12, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smorgick, N.; Marsh, C.A.; As-Sanie, S.; Smith, Y.R.; Quint, E.H. Prevalence of Pain Syndromes, Mood Conditions, and Asthma in Adolescents and Young Women with Endometriosis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2013, 26, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, J.W.; Howard, F.M.; Cross, R.K.; Good, J.L.; Weissman, M.M.; Wesselmann, U.; Langenberg, P.; Greenberg, P.; Clauw, D.J. Antecedent Nonbladder Syndromes in Case-Control Study of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome. Urology 2009, 73, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.C.; Chung, S.D.; Lin, H.C. Endometriosis Increased the Risk of Bladder Pain Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis: A Population-Based Study. Neurourol Urodyn 2018, 37, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, I.A.; Diokno, A.C.; Killinger, K.A.; Carrico, D.J.; Peters, K.M. Prevalence of Self-Reported Interstitial Cystitis (IC) and Interstitial-Cystitis-like Symptoms among Adult Women in the Community. Int Urol Nephrol 2007, 39, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontoravdis, A.; Hassan, E.; Hassiakos, D.; Botsis, D.; Kontoravdis, N.; Creatsas, G. Laparoscopic Evaluation and Management of Chronic Pelvic Pain during Adolescence. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 1999, 26, 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, M.K.; Jarnagin, B. Early Identification of Interstitial Cystitis May Avoid Unnecessary Hysterectomy; 2009.

- Patnaik, S.S.; Laganà, A.S.; Vitale, S.G.; Butticè, S.; Noventa, M.; Gizzo, S.; Valenti, G.; Rapisarda, A.M.C.; La Rosa, V.L.; Magno, C.; et al. Etiology, Pathophysiology and Biomarkers of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2017, 295, 1341–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.S.; Kotlyar, A.M.; Flores, V.A. Endometriosis Is a Chronic Systemic Disease: Clinical Challenges and Novel Innovations. The Lancet 2021, 397, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, N.F.; Gnanappiragasam, S.; Thornhill, J.A. Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome: The Influence of Modern Diagnostic Criteria on Epidemiology and on Internet Search Activity by the Public. Transl Androl Urol 2015, 4, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- As-Sanie, S.; Till, S.R.; Schrepf, A.D.; Griffith, K.C.; Tsodikov, A.; Missmer, S.A.; Clauw, D.J.; Brummett, C.M. Incidence and Predictors of Persistent Pelvic Pain Following Hysterectomy in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021, 225, 568.e1–568.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovall, T.G.; Ling, F.W.; Crawford, D.A. Hysterectomy for Chronic Pelvic Pain of Presumed Uterine Etiology. Obstetrics and gynecology 1990, 75, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Driscoll, A.; Teichman, J.M. How Do Patients with Interstitial Cystitis Present? J Urol 2001, 166, 2118–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.K. Interstitial Cystitis in Persistent Posthysterectomy Chronic Pelvic Pain. JSLS 2004, 8, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ceccaroni, M.; Bounous, V.E.; Clarizia, R.; Mautone, D.; Mabrouk, M. Recurrent Endometriosis: A Battle against an Unknown Enemy. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care 2019, 24, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizk, B.; Fischer, A.S.; Lotfy, H.A.; Turki, R.; Zahed, H.A.; Malik, R.; Holliday, C.P.; Glass, A.; Fishel, H.; Soliman, M.Y.; et al. Recurrence of Endometriosis after Hysterectomy. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 2014, 6, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R.J. Treatment Approaches for Interstitial Cystitis: Multimodality Therapy. Rev Urol 2002, 4, S16–S20. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).