Submitted:

12 July 2024

Posted:

15 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

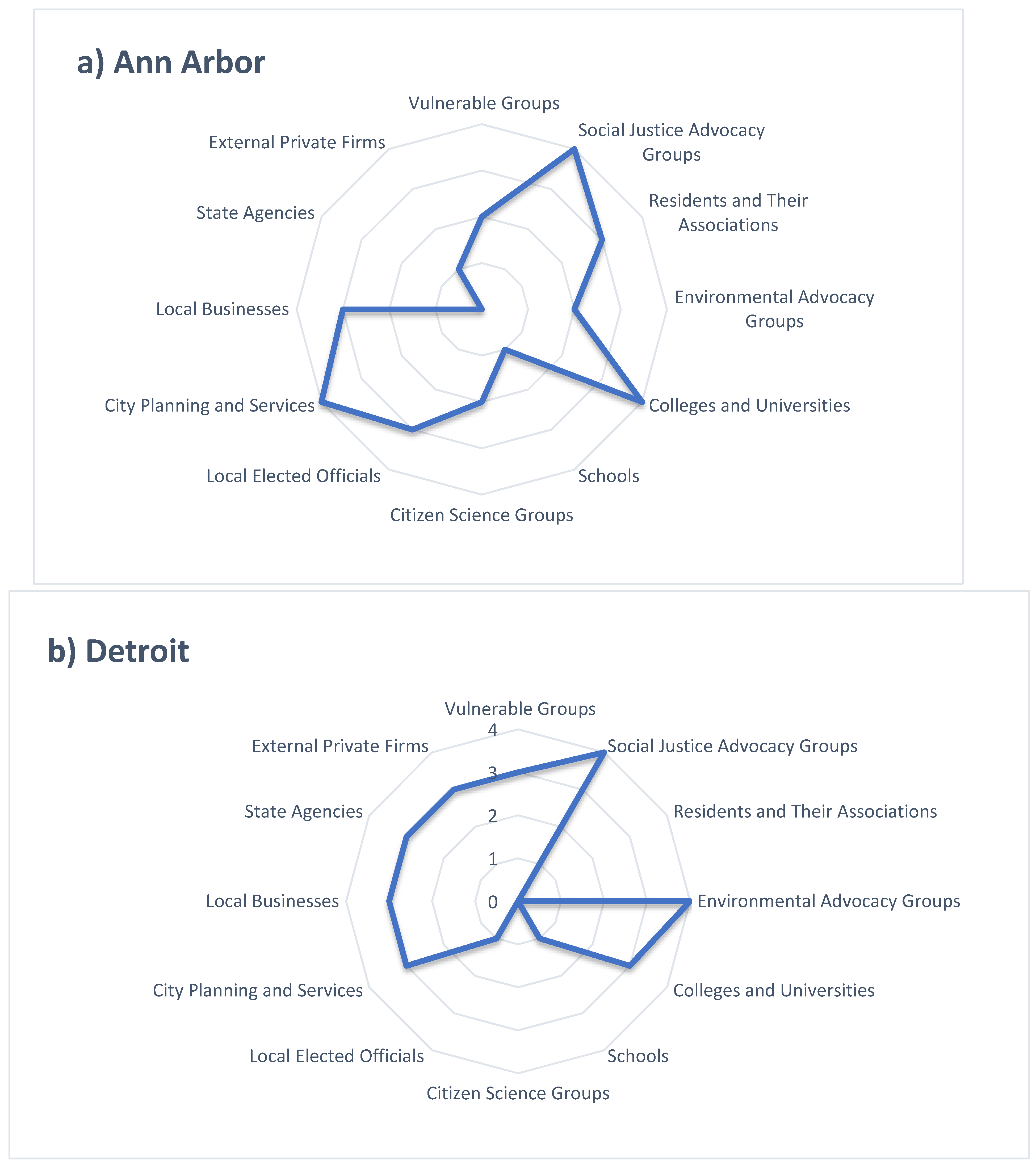

- How have Michigan cities addressed equity in their climate plans across various sectors and what groups of stakeholders have been included in the planning process?

- How the Two-Eyes Seeing approach reflected in the TCAM strategies could help cities to improve their planning efforts?

- To evaluate and compare consideration of equity in climate action and adaptation plans of Michigan cities.

- To evaluate and compare inclusion of various groups of stakeholders engaged in development of existing and forthcoming climate action and adaptation plans in Michigan; and

- To evaluate how the TCAM framework could inform and improve cities’ climate adaptation planning strategies.

2. Methodology

2.1. Selection of Climate Action and Adaptation Plans

2.2. Assessment Framework for Equity and Diversity of Stakeholders

2.3. Interviews and a Survey

3. Results and discussion

4. Conclusions

- Develop and enforce statewide guidelines that include DEI standards to ensure uniformity while allowing for adaptations to local conditions.

- Improve the capability of local governments to manage and implement climate strategies through comprehensive training and resources.

- Create forums for cities to share best practices and lessons learned, promoting a collaborative atmosphere that expedites the adoption of effective climate solutions.

- Establish formal collaboration frameworks between cities and tribal governments to ensure climate strategies are respectful and integrative of traditional ecological knowledge.

- Develop participatory planning processes that actively involve all community members, especially underrepresented groups, to ensure that diverse perspectives are considered in climate planning.

- Shift focus from planning to execution, with robust mechanisms to monitor and evaluate the impact of climate strategies, allowing for continuous feedback and improvement.

Acknowledgement

References

- ICLEI Local Governments for Sustainability, "Changing Climate Changing Communities: Guide and Workbook for Municipal Change Adaptation," ICLEI-Canada, 2019.

- M. Araos, L. Berrang-Ford, J. D. Ford, S. E. Austin, R. Biesbroek and A. Lesnikowski, "Climate adaptation planning in large cities: A ystematic global assessment.," Environmental Science and Policy, pp. 375-382, 2016.

- Georgetown Climate Center, "Adaptation Clearinghouse," 27 10 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.adaptationclearinghouse.org/.

- Sharifi, "Trade-offs and conflicts between urban climate change mitigation and adaptation measures: A literature review," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 276, p. 122813, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C.-F. Chi, S.-Y. Lu, W. Hallgren, D. Ware and R. Tomlison, "Role of Spatial Analysis in Avoiding Climate Change Maladaptation: A Systematic Review," Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 3450, 2021. [CrossRef]

- ADEME — Agence de la transition écologique, "Observatoire Territoires et Climat," 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.territoires-climat.ademe.fr/observatoire.

- National Institute for Environmental Studies, "A-Plat: Climate Change Adaptation Information PLatform," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://adaptation-platform.nies.go.jp/en/index.html. [Accessed 30 05 2024].

- R. Bierbaum, J. Smith, A. Lee, M. Blair, L. Carter, F. Chapin, P. Fleming, S. Ruffo, M. Stults, S. McNeeley, E. Wasley and L. Verduzco, "A comprehensive review of climate adaptation in the United States: More than before, but less than needed.," Mitigation and Adaption Strategies for Global Change, vol. 18, p. 361–406, 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Herrick and J. Vogel, "Climate Adaptation at the Local Scale: Using Federal Climate Adaptation Policy Regimes to Enhance Climate Services," Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 13, p. 8132, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Woodruff and M. Stults, "Numerous strategies but limited implementation guidance in US local adaptation plans.," Nature Climate Change, vol. 6, p. 796, 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. Lioubimtseva, "The role of inclusion in climate vulnerability assessment and equitable adaptation goals in small American municipalities," Discover Sustainability, vol. 3, no. 3, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE), "MI Healthy Climate Plan," 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.michigan.gov/egle/about/organization/climate-and-energy/mi-healthy-climate-plan. [Accessed 07 05 2024].

- Michigan Legislature, "Bills," 2023. [Online]. Available: https://legislature.mi.gov/Bills/. [Accessed 2024].

- Michigan Climate Action Council, "Michigan Climate Action Plan," 2009. [Online]. Available: https://uccrnna.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Michigan_2009_Climate-Action-Plan.pdf. [Accessed 07 05 2024].

- US EPA, "Summary of Inflation Reduction Act provisions related to renewable energy," 25 10 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/green-power-markets/summary-inflation-reduction-act-provisions-related-renewable-energy. [Accessed 13 03 2024].

- E. K. Chu and C. E. Cannon, "Equity, inclusion, and justice as criteria for decision-making on climate adaptation in cities.," Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, vol. 51, pp. 85-94, 2021. [CrossRef]

- AECF, "The Annie E. Casey Foundation," 16 October 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.aecf.org/blog/racial-justice-definitions?gclid=CjwKCAjw8KmLBhB8EiwAQbqNoHL0r04pzkQfSOyPGFt0r5_J3Ksk1JgEG84EQFCvCEiFp6CC4Qvm-BoCBA0QAvD_BwE.

- D. Reckien, S. Lwasa, D. Satterthwaite, D. McEvoy and F. Creutzig, "Equity, Environmental Justice, and Urban Climate Change," in Climate Change and Cities: Second Assessment Report of the Urban Climate Change Research Network, New York, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 173-224.

- Q. M. Roberson, "Disentangling the Meanings of Diversity and Inclusion," Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies/Cornell University Working Paper Series, Vols. CAHRS WP 04-05 , pp. 2-31, June 2004.

- Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan, "Adapt: Collaborative Tribal Climate Adaptation Planning.," 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.itcmi.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Climate-Adaptation-Planning-Booklet.pdf. [Accessed 10 04 2024].

- Tribal Adaptation Menu Team, "Dibaginjigaadeg Anishinaabe Ezhitwaad: A Tribal Climate Adaptation Menu," Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, Odanah, Wisconsin, 2019.

- T. McMillan, "Anishinaabe Values and Servant Leadership: A Two-Eyed Seeing Approach. The Journal of Values-Based Leadership.," The Journal of Values-Based Leadership, vol. 12, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Townsend , B. Kirk and M. Powers, "City of Traverse City Climate Action Plan," SEEDS Inc., Traverse City, MI, 2011.

- L. e. a. White, "Climate Adaptation in the Great Lakes Region A Case Study of Traverse City, Michigan.," University of Michigan School of Natural Resources and Environment., Ann Arbor, 2015.

- City of Grand Rapids, "Climate Action and Adaptation Plan," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.grandrapidsmi.gov/Government/Departments/Sustainability/Climate-Change/Climate-Action-and-Adaptation-Plan. [Accessed 12 05 2024].

- E. Lioubimtseva, "The role of inclusion in climate vulnerability assessment and equitable adaptation goals in small American municipalities," Discover Sustainability, vol. 3, no. 3, p. 1686, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Lioubimtseva and C. da Cunha, "The Role of Non-Climate Data in Equitable Climate Adaptation Planning: Lessons from Small French and American Cities," Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 2, p. 1556, 2023. [CrossRef]

- City of Ann Arbor Office of Sustainability and Innovations, "A2ZERO Action Plan 4.0," City Of Ann Arbor, Ann Arbor, 2020.

- PopulationU, " PopulationU.com," 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.populationu.com/cities/ann-arbor-mi-population. [Accessed 02 04 2024].

- U.S. Census Bureau, "QuickFacts: Ann Arbor City, Michigan," 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/annarborcitymichigan/PST045223. [Accessed 2 4 2024].

- Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice, "Detroit Climate Action Plan," DetroitEnvironmentalJustice.org, Detroit, 2017.

- U.S. Census Bureau, " QuickFacts: Detroit city, Michigan; United States.," 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/detroitcitymichigan,US/INC110222. [Accessed 2 4 2024].

- U.S. Census, "QuickFacts: Traverse City city, Michigan," 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/traversecitycitymichigan,wixomcitymichigan/LND110210. [Accessed 3 4 2024].

- H. Caggiano, D. Kocakuşak, P. Kumar and M. O. Tier, "U.S. cities’ integration and evaluation of equity considerations into climate action plans.," npj Urban Sustainability, vol. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Lioubimtseva and C. da Cunha, "Community Engagement and Equity in Climate Adaptation Planning: Experience of Small- and Mid-Sized Cities in the United States and in France.," in Justice in Climate Action Planning. Strategies for Sustainability., D. H. Petersen B., Ed., Springer, 2022, pp. 257-276.

- Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan, Inc., "Member Tribes," 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.itcmi.org/home/tribes/. [Accessed 25 06 2024].

- K. Sangha, I. J. Gordon and R. Constanza, "Ecosystem Services and Human Wellbeing-Based Approaches Can Help Transform Our Economies," Frintiers in Ecology and Evolution, vol. 13, pp. 1-11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians, "Climate Change Adaptation Plan," Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians, Gun Lake Tribe, 2015.

- Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, "Keweenaw Bay Indian Community Hazards Mitigation Plan," Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, 2021.

- Grand Traverse Band of Ottawaand Chippewa Indians, "Grand Traverse Band of Ottawaand Chippewa Indians Natural Hazard Mitigation Plans," Grand Traverse Band of Ottawaand Chippewa Indians, 2023.

- K. Menzies, E. Bowles, M. Gallant, H. Patterson, C. Kozmik and S. Chiblow, "“I see my culture starting to disappear”: Anishinaabe perspectives on the socioecological impacts of climate change and future research needs," FACETS, vol. 7, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, L. Shi, E. Chu, D. Gallagher, K. Goh, Z. Lamb, K. Reeve and H. Teicher, "Equity Impacts of Urban Land Use Planning for Climate Adaptation: Critical Perspectives from the Global North and South," Journal of Planning Education and Research, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 333-348, 2016. [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, "Climate Adaptation," 19 06 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/climate-adaptation.

- Institute for Local Government, "Climate Adaptation and Resilience," 26 10 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.ca-ilg.org/.

- California Energy Commission, State of California, "Cal-Adapt," 2021. [Online]. Available: https://cal-adapt.org/. [Accessed 5 7 2022].

- MICAN, "Michigan Communities Leading on Climate," Michigan Climate Action Network, 2022.

- E. Lioubimtseva and C. Da Cunha, "Local climate change adaptation plans in the US and France: Comparison and lessons learned in 2007-2017," Urban Climate, vol. 31, p. 100577, 2020. [CrossRef]

| City | Title | Goals | Year |

| Ann Arbor | A2Zero: Ann Arbor Living Carbon Neutrality Plan | Mitigation with elements of adaptation | 2020 |

| Detroit | Detroit Climate Action Plan: Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice | Mitigation with elements of adaptation | 2017 |

| East Lansing | Climate Sustainability Plan: Meeting our Climate Action and Green Community Goals | Mitigation with elements of adaptation | 2012 |

| Grand Rapids | Climate Action and Adaptation Plan | Mitigation and adaptation | 2024 (expected) |

| Marquette | Adapting to Climate Change and Variability | Adaptation | 2013 |

| Royal Oak | Royal Oak Sustainability and Climate Action Plan | Mitigation and adaptation | 2022 |

| Traverse City | City of Traverse City Climate Action Plan Climate Adaptation in the Great Lakes Region: A Case Study of Traverse City, Michigan |

Mitigation Adaptation |

2011 2015 |

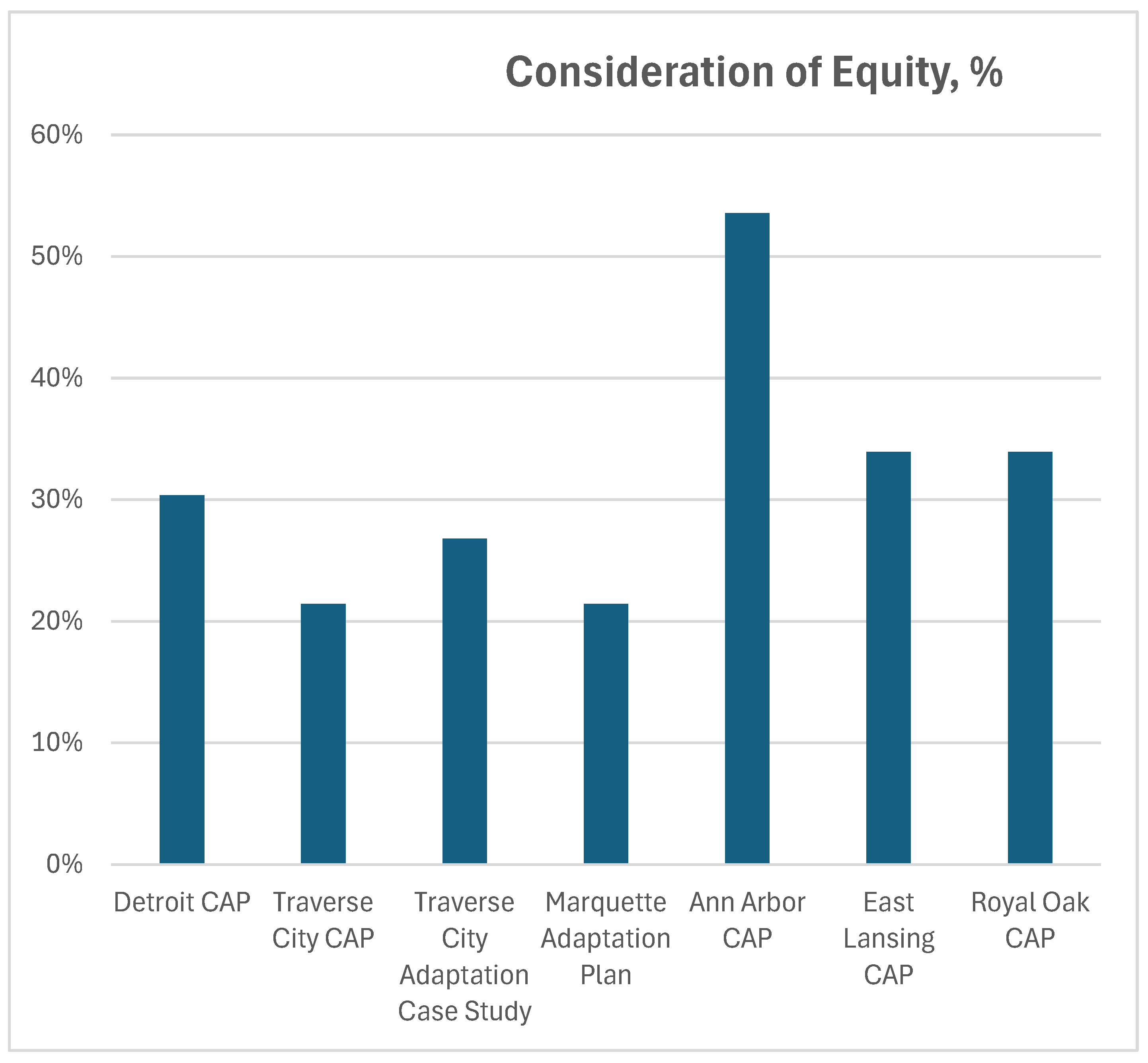

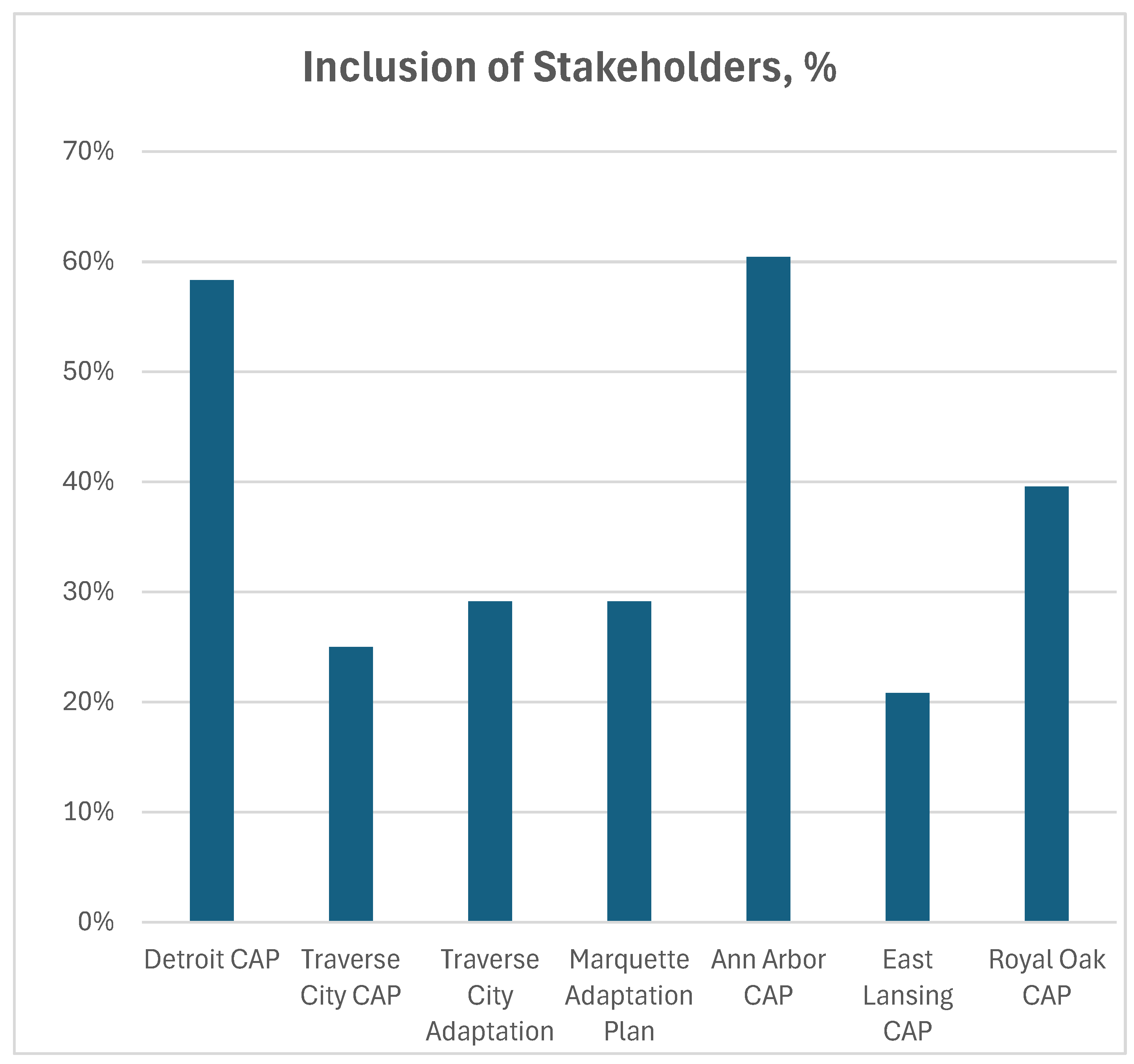

| # | Consideration of climate equity in each adaptation planning domain | Diversity and inclusion of stakeholders |

| 0 | Planning domain is absent | None |

| 1 | Planning domain is present in general, but does not address equity measures | Participant (attended community meetings, participated in surveys or interviews, recognized in the plan) |

| 2 | Planning domain is present, and equity is mentioned as a value or aspirational goal but strategies for achieving equity are not explained | Content co-creator (contributed specific data and information, referenced in the plan) |

| 3 | Planning domain is present and strategies for achieving equity are explained | Collaborator (engaged in decision making, acknowledged in the plan) |

| 4 | Planning domain is present and strategies for achieving equity are explained. Evaluation plan is provided. | Author/Co-author (listed on a cover page) |

| Participant | Equity Consideration | Collaboration Across Sectors | Inclusion of Stakeholders | Funding Sources | Specific Actions or Goals |

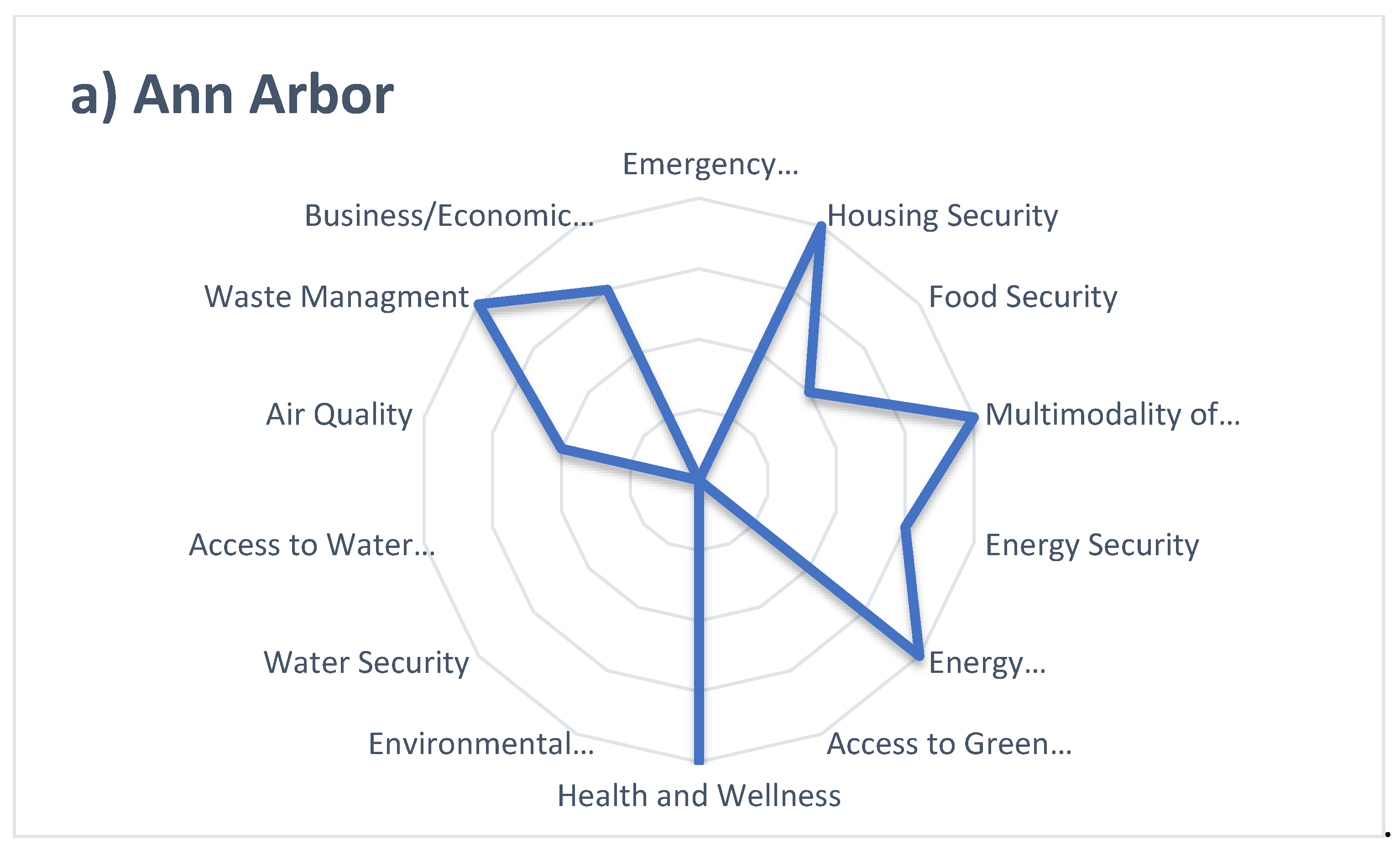

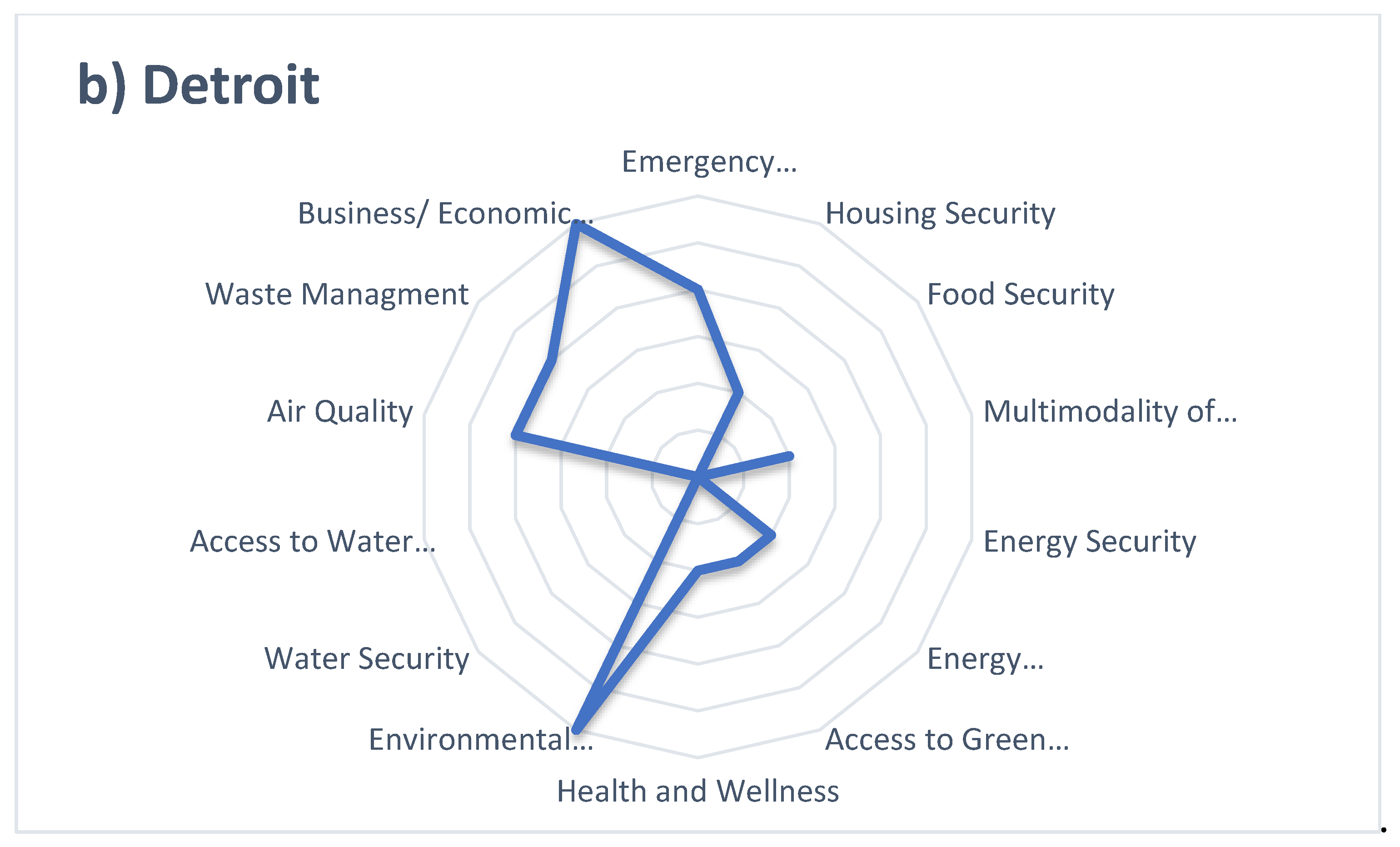

| 1 | Equity and adaptation recently integrated more deeply. Formation of a community steering committee shows a community-driven approach. | Focus on connecting housing to mobility and development of warming/cooling centers. Community-driven efforts highlighted. | Local officials and community groups' involvement emphasizes community-driven implementation. | Public and private funding with a focus on aligning with DEI goals. Highlights funding strategy aimed at equity. | Decarbonization and transportation improvements with community input. Reflects targeted action towards sustainability and equity. |

| 2 | Creation of equity frameworks for advisory teams to ensure decision-making includes equity. Partnership with C4 for diverse community voices. | Advisory teams with mixed expertise and resident experience for transportation planning. Emphasizes structured collaboration. | C4 ensures inclusion of diverse voices in planning. Reflects a partnership model for inclusivity. | Grants from foundations for projects indicate targeted funding approach. Partnership with C4 for specific community projects. | Sustainability and equity are key in the citywide strategic plan, indicating an integrated approach to planning. |

| 3 | Focus on initiatives like the '0' program for energy efficiency in low-income areas. Proactive community engagement for BIPOC inclusion. | BIPOC community engagement for input into planning through surveys and sessions. Specific efforts to engage underrepresented communities. | Efforts to include BIPOC communities through targeted engagement strategies. Focus on accessible participation. | Mentions possible federal funds without specifics. Indicates a need for exploring diverse funding sources. | Energy efficiency pilot projects in focus neighborhoods. Demonstrates actionable steps towards equity in climate action. |

| 4 | Each action in the climate plan has an equity section, emphasizing a systematic integration of equity across the board. | Wide range of stakeholders involved, including housing commissions, CBOs, and universities, illustrating an inclusive collaboration approach. | Rethought engagement for inclusivity with tactical models and targeted outreach. Engagement positions outside traditional settings. | Climate tax and philanthropic funding for community partners. Innovative funding approaches for community-based initiatives. | Actions include energy, circular economy, and comprehensive engagement. Highlights a holistic approach to climate action. |

| 5 | Prioritizations of equitable climate solutions by engaging with financially constrained communities, ensuring climate actions benefit those who need it the most. | Involvement in multi-city pilot programs, particularly in the area of waste management and sustainability. They also work with labor unions and housing commissions. | Advocating for union participation in green installations and fostering community engagement. Various stakeholders, including those from labor, housing, and marginalized communities, have a voice in climate action planning and implementation. | Utilized philanthropic funds for climate advocacy and has adapted to incorporate various public funding sources. Strategic use of county rebates and city mileages, which provided significant financial resources for Ann Arbor's sustainability office and their climate action efforts. | Actions include advocating for the development of affordable, green housing projects, contributing to public policy for sustainable city planning, and engaging in community projects such as the establishment of resilience hubs and tree planting campaigns to mitigate the heat island effect and enhance urban green spaces |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).