1. Introduction

In the city transition, the issue of sustainable development requires improving the quality of life, including improving urban green spaces in urban areas [1-12]. The green space is fundamental for a sustainable city and community [

6]. Another urban planning has a significant role in retaining and maximizing urban green space [5-13]. Furthermore, the role of urban planners is to promote a strategic vision of sustainable development. By determining and implementing interdependent uses, urban planner aims to resolve conflicts between different interests. According to Campbell, urban planners are a central part of the triangle model in which they work for “environmental protection, economic development, and social justice” [

13]. In addition, the physical environment is one of the crucial tasks of sustainability in governance equilibrium tetrahedron [

14]. Peters pointed out that city authorities and institutions have a significant role in sustainable development and urban planning is related to city government. The elected city government has a majority. Thus, municipal authorities and "visionary leaders" are the leading actors in strategic planning regarding development [

15].

Land use planning is the most powerful tool for urban planners [

13]. However, land-use policy domains have been incoherent green space policies. Another legal protection for green space is insufficient, and the property structure is fragmented [

6]. The issue of land use is to determine the distinction between the public and the common good [16-17]. Public spaces in the city have always been at the center of attention of the city authorities. However, these spaces and goods do not necessarily create common goods. In the urban practice of creating common goods, the principle applies that the relationship between a social group and an aspect of the environment treats common goods for all. In addition, common goods will not be subject to trade beyond the market exchange and valuation.

In the post-socialist sustainable transition, urban theories are influenced by crises in other ways. The post-socialist crises are reflected in the chaotic urban development, which is the weakening of the state as a central entity and, on the other hand, the arbitrariness of the city administration [

18]. The main issue with public policy in the post-socialist context of sustainable development is whether the spatial, institutional, and action capacities of the public sector from national to local. The disconnection between policies is reflected in the poor formulation, implementation, and regulation of urban development in post-socialist cities [

19]. The transfer of responsibility at the national and local levels often favors the interests of private investors instead of protecting public space [18-19].

By contrast to Western European cities, the transition to a new framework weakens the authority of professionals to regulate initiatives based on professionalism. In addition, urban planners lose their professional autonomy. Thus, urban planners focus on land-use-oriented planning that supports market-oriented issues [

20]. This research hypothesizes that post-socialist city planning reduces urban green areas due to the lack of new mechanisms in documents for the planning of urban green space. In the post-socialist city, urban planners "need to redefine their role from reactive guardians who serve the interests of the political and economic elite to active defenders of public interests [18-19]. Urban planners must implement their cultural capacities to improve the degree of professional autonomy [18-21].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Studies

Belgrade was selected as a post-socialist city of the former Yugoslavia to analyze the reduction of urban green spaces in the post-socialist transition. To understand the dynamics of changes in the planning documents, we define two contexts for analysis: socialist and post-socialist contexts. The socialist context includes the period from 1974 (the new concept of work and social agreements) to 1990 (the breakup of Yugoslavia and the collapse of the socialist system of government). The post-socialist context analyzes the period since 2000 and the new concept of the neoliberal capitalist system.

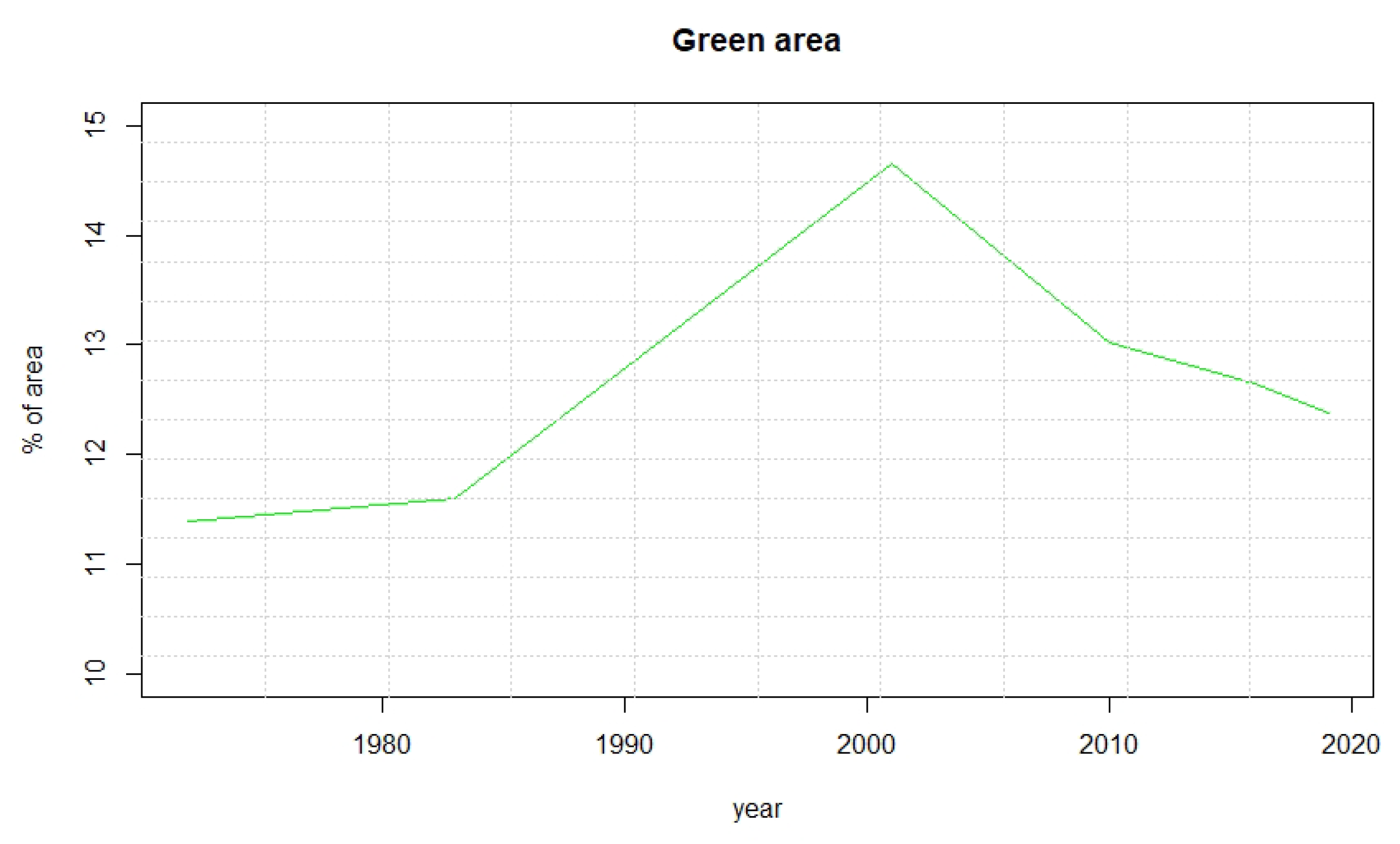

Figure 1 presents the percentage of green areas from 1974 to 2020. The dynamics of change in the post-socialist context are fast decreasing.

2.2. Interviews

This research applied a semi-structured interview as a qualitative research method. The criteria were chosen for structuring the questions into four categories: strategic, spatial, institutional, and social. The first criterion analyzes the dynamics of change in strategic vision and how urban planners participate in defining strategic vision. The second criterion analyzes how urban planners design and implement a plan for urban green areas. The third criterion analyzes the role of urban planners in the institutional context and identifies institutional barriers through urban legislation and planning. The fourth criterion analyzes the role of urban planners through citizens' participation in planning.

Criteria of selection of respondents:

Urban experts/planners from various fields: urban sociology, spatial planning, urban planning, architecture and landscape architecture;

Urban experts/planners from various institutions: faculties/institutes, Urban Institutes, city administration, and civil sector organizations;

Significant experience in urban development in the socialist and post-socialist context, urban practice in planning and implementation of planning documents, and planning with citizens.

The research is based on semi-structured interviews with ten urban planners. The interviews were realized in the period from January to April 2022. All respondents have a university education and significant experience in the urban development of Belgrade. Respondents who include group A are respondents from academic institutions (3 respondents are professors, of which one is retired). The work experience of respondents of group A is over 35 years of work in the profession. Respondents who include group B are respondents from the city administration and urban planning institutions (three are urban planners, of which three are retired from the city administration, and two are from the urban planning institute). The work experience of respondents of group B is over 35 years and over 15 years in the profession. Respondents in group C are respondents from the civil sector with experience working in the urban planning institute (two respondents). The work experience of respondents of group C is over 15 years of work in the profession.

Table 1.

List of respondents.

Table 1.

List of respondents.

| Group |

Affiliation |

Institution |

Experiences |

| A [22]

|

Urban sociologist

Professor |

Institute for Sociologist Research |

>35 years

|

| A [23]

|

Spatial&urban planner

Urban expert |

Institute of Architecture, and Urban & Spatial Planning |

>35 years |

| A [24]

|

Professor

Urban expert

Professor |

Faculty of Architecture,

University of Belgrade |

>35 years |

| B [25]

|

Urban planner |

City administration

Urban planning institute |

>35 years |

| B [26]

|

Urban planner |

City administration |

>35 years |

| B [27]

|

Urban planner |

City administration |

>35 years |

| B [28]

|

Urban planner |

Urban planning institute |

>15 years |

| B [29]

|

Landscape architect |

Urban planning institute |

>15 years |

| C [30]

|

Urban planner |

NGO |

>15 years |

| C [31]

|

Urban planner |

NGO |

>15 years |

3. Results

3.1. Perceptions of Urban Experts from Academic Institutions

The main problem of reducing urban green spaces in a post-socialist city such as Belgrade is the systematic change in the land [

22]. The post-socialist transformation brings a new valorization of the land. Land becomes a commodity, use value is left aside, and traffic is primary. In the era of socialism, private property did not exist. In the socialist city, land was valued differently and developed according to its principles and standards [22-23]. As a result of the changes in the post-socialist city, the land becomes a commodity, resulting in valuable locations that can bring the highest rent, profit, commercial facilities, luxury housing, etc. A decrease in green space becomes equivalent to an increase in investors' profits, and investors pay more to use the land for construction. Urban areas that are not profitable are excluded, such as urban green spaces. Regarding the planning of urban green spaces, Stojkov proposes introducing the concept of common land as part of the urban legislation [

23].

In the era of post-socialism, urban planners have identified a problem of weak city institutions. The public interest is threatened by political influence. Under the influence of international organizations and pressures on the public sector, abolish and weaken control mechanisms [

24]. For illustration, the Republican Agency for Spatial Planning, introduced at the initiative of spatial and urban planners in the urban legislation in 2003, was abolished because it began to "interfere" in spatial plans for political purposes, which are in the hands of politicians and capital. Another institution, the Urban Institute of Belgrade, which was a professional institution, lost its reputation and authority. Namely, in the post-socialist period, the Urban Institute became an administrative institution as a good government mask, which works for the highest levels of government, incomparable to the role of the Institute from the previous period, in the late seventies and early eighties [

23].

Urban planners have always subordinated to politics. In socialism, in a highly politicized society (politics was the dominant field), the professional autonomy of urban planners has been respected. During socialism, architects and urban planners made very unusual developments [

22]. With the transition to the post-socialist phase, the profession experienced a decline and even greater subordination to interest. Directly from the politicians, the capital occupied place [

24]. The double coordination of urban planners toward capital through politics significantly narrows the autonomy of expert competence [

22]. As a result, urban planners have a template for each planning document and an administrative procedure for creating plans by command. Thus, urban planners spend the least time on development and planning because the actors of urban legislation seek to shorten the procedures for issuing permits [

23]. Technical standards are social. In other words, by reducing planning to technical determinism, “we can do what we want with urbanism.” [

22]

With the transition to the post-socialist period, one of the problems in city institutions is the separation of preparation and implementation of planning documents. While urban planners from public and private companies plan, on the other hand, the city administration implements the plans. Urban planners who participate in the development of plans have no feedback on how planning documents are implemented. There is no synergy between feedback that causes problems and the system that forms creates parallel institutions, procedures, and instruments [

24].

According to urban experts, public interest cannot exist without elementary trust in social communities, citizens, and responsibility. That is why urban planners must have an autonomous field. Without that autonomy, they cannot communicate and achieve two-way communication (who makes the decisions - the city government, and who is affected by the decisions - the citizens). Urban planners must have an institutional background to show critical and respect it [

22]. However, there must be trust between those who make decisions in institutions and those who plan. The role of academic institutions should be one of the capillary contributions in the future as a form of strengthening institutions. Following the question of the role of urban planners, urban planners need a new instrument in planning, which implies a balance between the private and civil sectors [

24].

In conclusion, the role of urban planners is to find a common denominator between the public interest, citizens, investors, and spheres of established program development principles of international institutions. In addition, the role is to reach the public to the common interest so that some common interests are not expensive of fragmented private interests [

24]. From the aspect of the civil sector, urban experts pointed out that activism is the main issue, and active participation of citizens can achieve results in planning, especially in planning urban green spaces. The urban legal procedure foresees three stages (decisions, early public insight, and public insight), and city institutions should provide opportunities for implementation [

24]. Furthermore, the role of the civil sector is in essential institutional changes and as a bearer of institutional changes and improvement of the quality of the role of urban planners in planning.

Table 2.

List of tasks of group A. Source: adapted based on [22-24].

Table 2.

List of tasks of group A. Source: adapted based on [22-24].

| Criteria |

Task |

| Strategic |

Strategic vision

New valorization of land: common land

Professional autonomy of urban experts and urban planners

Professional autonomy of urban institution

|

| Spatial |

Introduce technical standards in urban planning as a social |

| |

|

| Institutional |

Abolish parallel institutions, procedures and instrument

Establish control mechanism in urban legislation

Strengthen city institutions by cooperating with academic institutions |

| Social |

Active participation of citizens in urban planning |

3.2. Perceptions of Urban Planners from City Administration

This part of the analysis deals with the perception of urban planners from different city institutions and levels of government. Based on the analysis of respondents, urban planners identified several problems in reducing green areas in the city:

Lack of strategic vision of the city

Investor urbanism

Innovative planning documentation

Lack of typology of urban green spaces

Lack of a spatial database

Lack of cooperation between urban planners of different professions

Lack of cooperation between urban planners of different institutions

Lack of cooperation between different departments within the city administration.

Implementing a strategic vision in urban planning is one of the main parts of sustainability. In the neoliberal capitalist concept, the driver of the construction industry is private capital. It needs to understand the issues of the city's development priorities in creating a strategic vision. The city government should have a clear strategy for the city's development priorities, while urban planners should implement this [25-29]. According to urban planners from the Institute of Urban Planning, the main problem of decreasing urban green spaces in Belgrade is the city's expansion [28-29], financed by private capital [

25]. Therefore, the construction zone within the planning documents is increasing, which decreases urban green spaces. For illustration, green areas within open blocks (built-up blocks) decrease, and new building zones are created through innovative planning documentation. When preparing planning documents, urban planners are often under pressure from investors (interested groups), city authorities (politicians), and even citizens [

25]. Urbanism, as noted by urban planners in new planning documents, is the trend of decreasing urban green spaces and planning according to minimalism [25-29]. Thus, urban planning becomes a "service" for investors, which creates as many square meters of residential and business space as possible. As a result, urban parameters increase in planning documents, which represents pressure on infrastructure, including green infrastructure [25-26]. Another problem of decreasing urban green spaces is a consequence of urban legislation adopted in 2003, which deletes the protection of the common good and public interest and introduces the interest of investors. In urban legislation, it is necessary to mark green spaces as an interest of public health [

26].

The lack of data on green spaces by institutions, the inconsistency in the typology of green space, and the unregulated cadastral state of green space are some of the problems in planning urban green spaces. There is no database on green spaces, and the typology of green space differs between different institutions [

28]. On the other hand, the lack of cooperation in the planning process within the Urban Institute between urban planners and landscape architects does not exist [

29], and the low initiative of urban planners and landscape architects to plan urban green spaces [

28]. Furthermore, there is a lack of communication between the urban planners who make the plan and the urban planners who implement the plan. Due to the institutional separation of the preparation and implementation of planning documents, there is no possibility of the Urban Institute's insight into planning decisions during the implementation of plans by the city administration [

29]. There is no intersectional cooperation when it comes to the implementation of plans within the competent institutions of the city administration. For illustration, according to green spaces, the Secretariat for Urban Planning plans while the Secretariat for Communal and Housing Affairs implements those [

26]. In urban legislation, participation as a model of civic control should be the standard [26-29]. Urban planners must be crucial in planning urban green spaces, and city government should follow them. Specifically, everyone's role should show the connection and interaction of three groups: citizen-urban planners, citizen-administration, and urban planners-administration [

25].

Table 3.

List of tasks of group B. Source: adapted based on [25-29].

Table 3.

List of tasks of group B. Source: adapted based on [25-29].

| Criteria |

Task |

| Strategic |

Strategic vision (strategic priorities: public health) |

| Spatial |

Typology of urban green space

Database of urban green space |

| Institutional |

New mechanism in urban planning |

| Social |

Participation as a model of civic control |

Figure 1 presents the percentage of green areas from 1974 to 2020. The dynamics of change in the post-socialist context are fast decreasing.

3.2. Perceptions of Urban Planner from Civic Sectors

This part of the analysis deals with the perception of urban planners from the civil sector. Based on the analysis of respondents, urban planners identified several problems in decreasing urban green spaces in the city:

Land-use policy

Innovative planning documentation

Decision-making process

Urban parameters of green spaces

No active participation of citizens in green planning.

According to the opinion of urban planners who are part of the civil sector, everything related to the public interest, such as urban green spaces, is on the second plan and is not systematically supported. Urban green spaces decrease by the influence of private investments and private capital. Furthermore, land-use policy focuses on capital, and one of the main goals is the maximum profit use of space [30-31]. Because planning documents are a tool for politicians to change the land, planning has become instrumental in politics in legitimizing political decisions [

30]. For illustration, a politician can submit an amendment to the adopted plan despite being accepted by urban expert control. This amendment requests the amendment of the paragraph of the plan, which relativists the entire planning document.

Additionally, innovative planning documentation became part of the urban legislation and the role that spatial planners, urban planners, and landscape architects should play in the plan. Therefore, the profession must confirm the political decision through a technical solution. Urban planners cannot criticize it or give different arguments. Thus, the decision-making process is problematic and favors investors. Decisions are made ad hoc, without analysis, statistics, or studies. There is no input data, only formal documents as legal documents in planning [30-31]. As a result, each proposal can change and adopt a completely different solution than the urban planners' suggestion. Moreover, legal solutions created a conflict of interest [

30].

Furthermore, urban planners indicate that urban parameters of urban green spaces are not the result related to the norm about the number of inhabitants and are not strategic. According to urban planners from civic sectors, the parameter requires strategic implementation and cannot be implemented equally from location to location. As a solution, urban planners highlight the creative power of citizens and the civil sector in planning. The rule of city government should be to provide the active participation of citizens in planning because, in urban practice, participation is the legal minimum. Due to dissatisfaction, citizens increasingly use initiatives, and urban planners do not have the mechanism in these newly created situations.

Table 4.

List of tasks of group C. Source: adapted based on [30-31].

Table 4.

List of tasks of group C. Source: adapted based on [30-31].

| Criteria |

Task |

| Strategic |

Land-use policy

Decision-making process |

| Spatial |

Parameter of urban green space |

| Institutional |

New mechanism in implementation |

| Social |

Active participation of citizens in urban planning |

4. Discussion

Post-socialist society is a pre-political society that has not gone through the evolutionary path of developing institutions for the new neoliberal concept. In contrast to the neoliberal capitalist system, in socialism, the high level of that political society is the national government's favor of the public interest and the welfare state. In the neoliberal concept, when capital begins to impose itself more directly on the public sector, the public sector is more forced to cooperate with the private sector because it has to provide more diverse services. Thus, urban planners need to find a common denominator between public interest, citizens, investors, and spheres determined by the sustainability principles of the development. The importance of a society is to develop and apply standards to protect the public sector in market democratic systems.

According to respondents, the role of urban planners needs to be systematically (re)started in the post-socialist city. First, defining strategic vision should be the starting point for urban planners. Still, the city authorities are actors in the strategic planning of the city development. For a strategic vision, it is necessary to involve several interested parties, and urban planners should have a central place between city authorities and citizens. Respondents from group A agreed that academic institutions should be involved in the city's strategic plan as one of the capillary contributions in the future as a form of strengthening institutions. The vision must be a process of participation and consideration of different actors in the city. Respondents from group C believe that urban planners should use the creative energy of citizens in future perspectives of urban development. It highlights the importance of community participation by promoting local culture and social values by organizing urban green spaces that will enable the diverse activities of city residents. In this way, it could reduce conflicting interests and establish a socio-economic balance that is very crucial in terms of defining urban green policy. Urban renewal, as one of the strategic decisions, implies consideration of every civic initiative and acceptance of it by the urban planning profession.

The research showed that land-use policy has a significant role in post-socialist urban transformation. A respondent from group A suggested that urban green space gets a new status as common land. Thus, the principle applies that the relationship between a social group and an aspect of the environment treats common goods for all. Common land will not be subject to trade beyond the market exchange and valuation. By analyzing the interviews of respondent B, the land-use policy domains have been incoherent in green space policies. Furthermore, urban planners focus on land-use-oriented planning that supports market-oriented issues. An integrated approach to urban green space planning is to balance social with environmental and to combine techniques and skills by balancing spatial and socio-ecological issues.

Planners need to understand planning as a social standard. Therefore, the green parameter requires strategic formulation defining the index of urban green space as a form of control of the built-up area and urban green space related to the number of inhabitants.

In conclusion, urban planners need a new mechanism to balance the private and civil sectors. Moreover, the role of urban planners is to restore participation in local communities and conduct public consultations with citizens. City authorities should provide opportunities for those standards. With a new approach, both urban planners and city authorities would work on the concept of a sustainable and green city.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.; methodology, S.M.; validation, S.M. and K.S.; formal analysis, S.M.; investigation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, I.C., K.S. and A.D..; visualization S.M.; supervision, I.C, K.S. and A.D.; project administration, I.C. and A.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by Seoul Metropolitan Government under the International Cooperation Fund-ODA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, W.; Wu, T.; Li, Y.; Xie, S.; Han, B.; Zheng, H.; Ouyang, Z. Urbanization Impacts on Natural Habitat and Ecosystem Services in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao “Megacity”. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Martín, E.; Giordano, R.; Pagano, A.; van der Keur, P.; Máñez Costa, M. Using a system thinking approach to assess the contribution of nature based solutions to sustainable development goals. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 139693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolch, J. R. , Byrne, J. , & Newell, J. P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landscape and urban planning 2014, 125, pp. 234–244. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, P.Y.; A Diehl, J. A conceptual framework for studying urban green spaces effects on health. J. Urban Ecol. 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baycan-Levent, T. , & Nijkamp, P. Urban green space policies: performance and success conditions in European cities. 2004.

- Kwartnik-Pruc, A.; Trembecka, A. Public Green Space Policy Implementation: A Case Study of Krakow, Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidt, V.; Neef, M. Benefits of Urban Green Space for Improving Urban Climate. In Ecology, Planning, and Management of Urban Forests; Carreiro, M.M., Song, Y.C., Wu, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Lafortezza, R. Urban green infrastructure in Europe: Is greenspace planning and policy compliant? Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, J. Why not to green a city? Institutional barriers to preserving urban ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, J. The role of local government greening policies in the transition towards nature-based cities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2020, 35, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, K.; Sbarcea, M.; Panagopoulos, T. Creating Green Space Sustainability through Low-Budget and Upcycling Strategies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- aldarović, O. , & Šarinić, J. Socijalna važnost prirode u urbanom kontekstu. Društvena istraživanja: časopis za opća društvena pitanja, 19(4-5), 2010, pp. 733-747.

- Campbell, S. Green Cities, Growing Cities, Just Cities? Urban Planning and the Contradictions of Sustainable Development. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1996, 62, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contin, A. , & Ortiz, P. B. New metropolitan discipline: Foundational significance of Madrid 2016 Plan. Urban, (08-09), 2016, pp. 125-153.

- Pieterse, D. E. City futures: Confronting the crisis of urban development. Zed Books Ltd., 2013, pp.84-107.

- Harvey, D. Rebel cities: From the right to the city to the urban revolution. Verso books, 2012.

- Josifidis, K. Losonc, A. Neoliberalizam sudbina ili izbor. Graphic, Novi Sad, 2007, pp. 204-212.

- Stanilov, K. (Ed.) . The post-socialist city: urban form and space transformations in Central and Eastern Europe after socialism (Vol. 92). Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- Petrovic, M. Transformacija gradova: Ka depolitizaciji urbanog pitanja. Beograd: Institut za socioloska istrazivanja, Filozofski fakultet, 2009, pp.55-69.

- Nedović-Budić, Z. Adjustment of Planning Practice to the New Eastern and Central European Context. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2001, 67, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujosevic, M. Petovar, K. Javni interes i strategije aktera u urbanistickom i prostornom planiranju. Sociologija, Vol. XLVIII (4), 2006, pp.357-382.

- Petrovic. M. 2022. interview by Sladana Milovanovic in 2022.04.14.

- Stojkov. B. 2022. interview by Sladana Milovanovic in 2022.02.04.

- Colic. R. 2022. interview by Sladana Milovanovic in 2022.04.21.

- Novakovic. Lj. 2022. interview by Sladana Milovanovic in 2022.04.10.

- Vujosevic. N. 2022. interview by Sladana Milovanovic in 2022.04.07.

- Popovic. N. 2022. interview by Sladana Milovanovic in 2022.03.17.

- Lazovic. A. 2022. interview by Sladana Milovanovic in 2022.02.16.

- Jeftic. N. 2022. interview by Sladana Milovanovic in 2022.01.31.

- Graovac. A. 2022. interview by Sladana Milovanovic in 2022.04.18.

- Zindovic. M. 2022. interview by Sladana Milovanovic in 2022.01.24.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).