Submitted:

12 July 2024

Posted:

15 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Design of the Training Capsule

2.3. Assessment of the Training Capsule

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Bibliographic Search

3.2. Preparation of Teaching Materials

3.2.1. Basic Introduction of Theoretical Concepts

3.3. Design of the Session

3.3.1. Step 1. Who Is Who and Clinical Settings (15 Minutes)

3.3.2. Step 2. Theory (45 Minutes)

3.3.3. Step 3. Practicum (1 Hour)

- 1)

- The acquisition and unification of recognition criteria of the three elements of non-verbal communication on which the PAIC scale is based: facial expressions, body movements and vocalizations.

- 2)

- The identification of these components in clinical cases demonstrates their validity for differential diagnosis, overcoming confounding intrinsic/extrinsic factors (i.e., facial expression and posture in old age, environmental noises, etc).

- 3)

- The applicability in the clinical environment in a situation of rest and transfer (chair-to-chair or chair-to-bed displacements, for example).

- 4)

- Specific observation 1: Pain assessment in cognitive impairment can be challenging: To observe the difficulty in detecting pain (when it is present, but not obvious), also assessing the degree of reliability of the verbal response given by the patient. Using the PAIC 35 can help to gain skills for this type of assessment.

- 5)

- Specific observation 2: Incongruence between verbal self-report and non-verbal response: To contrast the non-verbal response (measure with the PAIC observational scale, in its three components) and the verbal response (VAS scale, the most used, as the standard).

- 6)

- Specific observation 3: PAIC 35 intersubject validity with/without pain in a situation of rest: To recognize the observable changes in the facial and body components and the vocalizations in the same patient in two rest situations, one in which it is known that there is pain and a second one where it is known that there is no pain.

- 7)

- Specific observation 4: PAIC 35 intersubject validity with/without pain during a transfer: To recognize the observable changes in the facial and body components and the vocalizations in the same patient in a new situation that implies transfer and possible elicitation of pain.

- 8)

- Specific observation 5: Rest and transfer conditions comparison: To contrast the changes in PAIC 35 observed in one situation (resting) and another (transfer) and assess whether there is a correlation between them.

- 9)

- Specific observation 6: PAIC 35 in experimental pain: To observe that in front of mild pressure stimuli (2 Kpa) in the shoulder administered with an algesimeter, the verbal and non-verbal response can be of null perception, hyperalgesia or normal, as compared to healthy controls.

- 10)

- Simplification to PAIC 15. Once the criteria and skills were trained, the PAIC 15 brief version was presented to the participants, to highlight the most important items of observation and the time feasibility of its use. Thereafter, students were informed that they could further increase the reliable handling of the PAIC 15 scale through a 30-minute free online training available at https://paic15.com/e-training/

3.4. Assessment of the ‘Training Capsule’

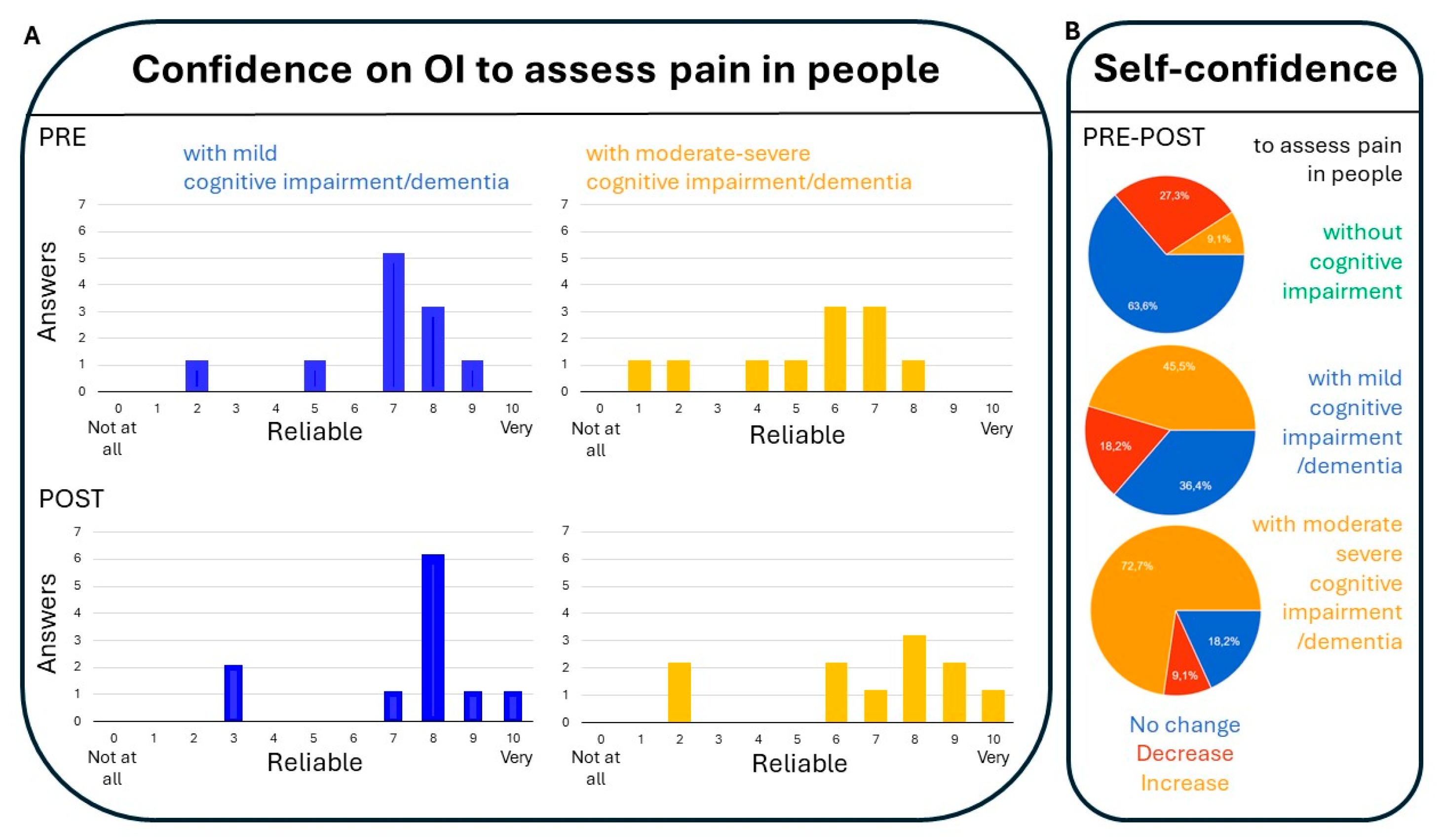

3.4.1. Confidence on Observational Items (OI) to Assess Pain in People with Mild Cognitive Impairment/Dementia and Those with Moderate Impairment (Figure 1):

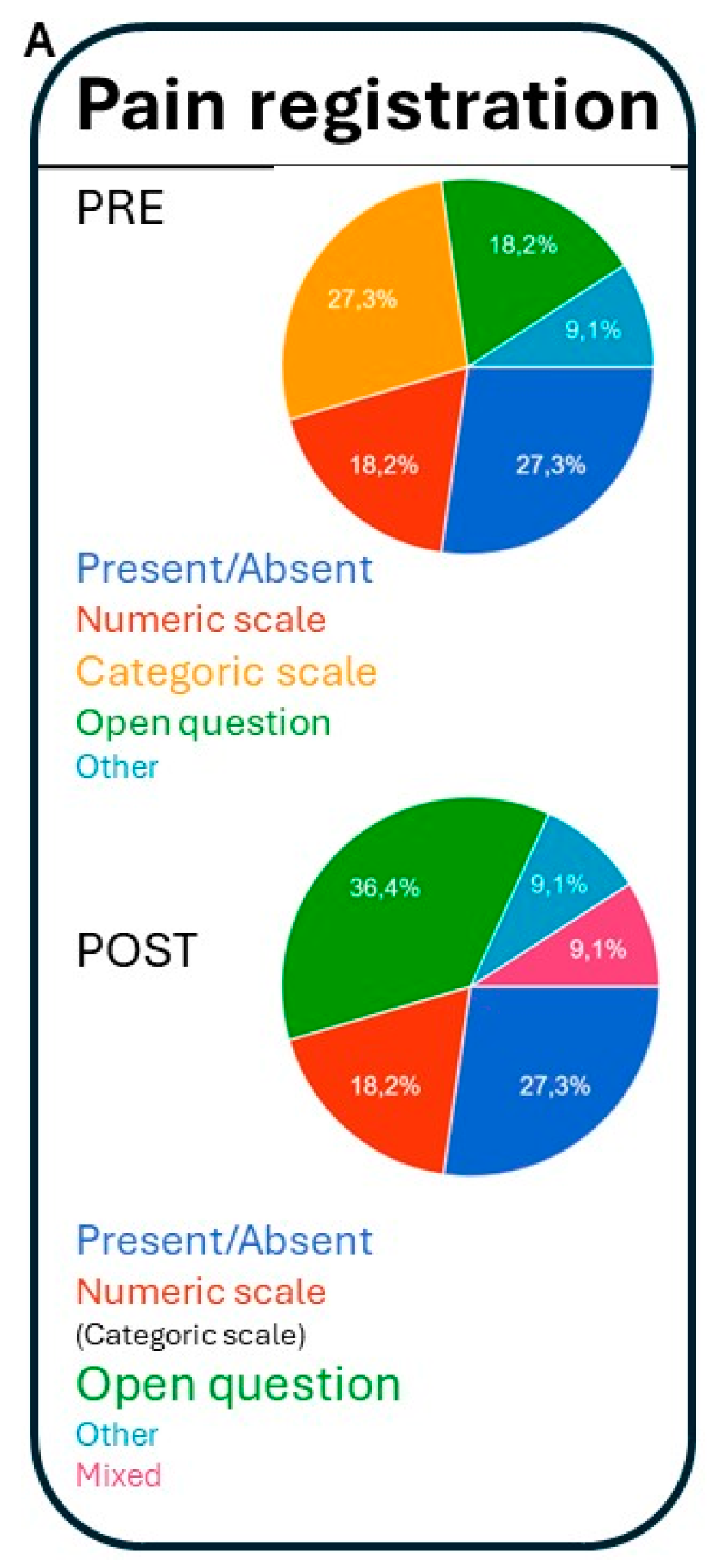

3.4.2. Professional Preference About How to Register Pain (Figure 2):

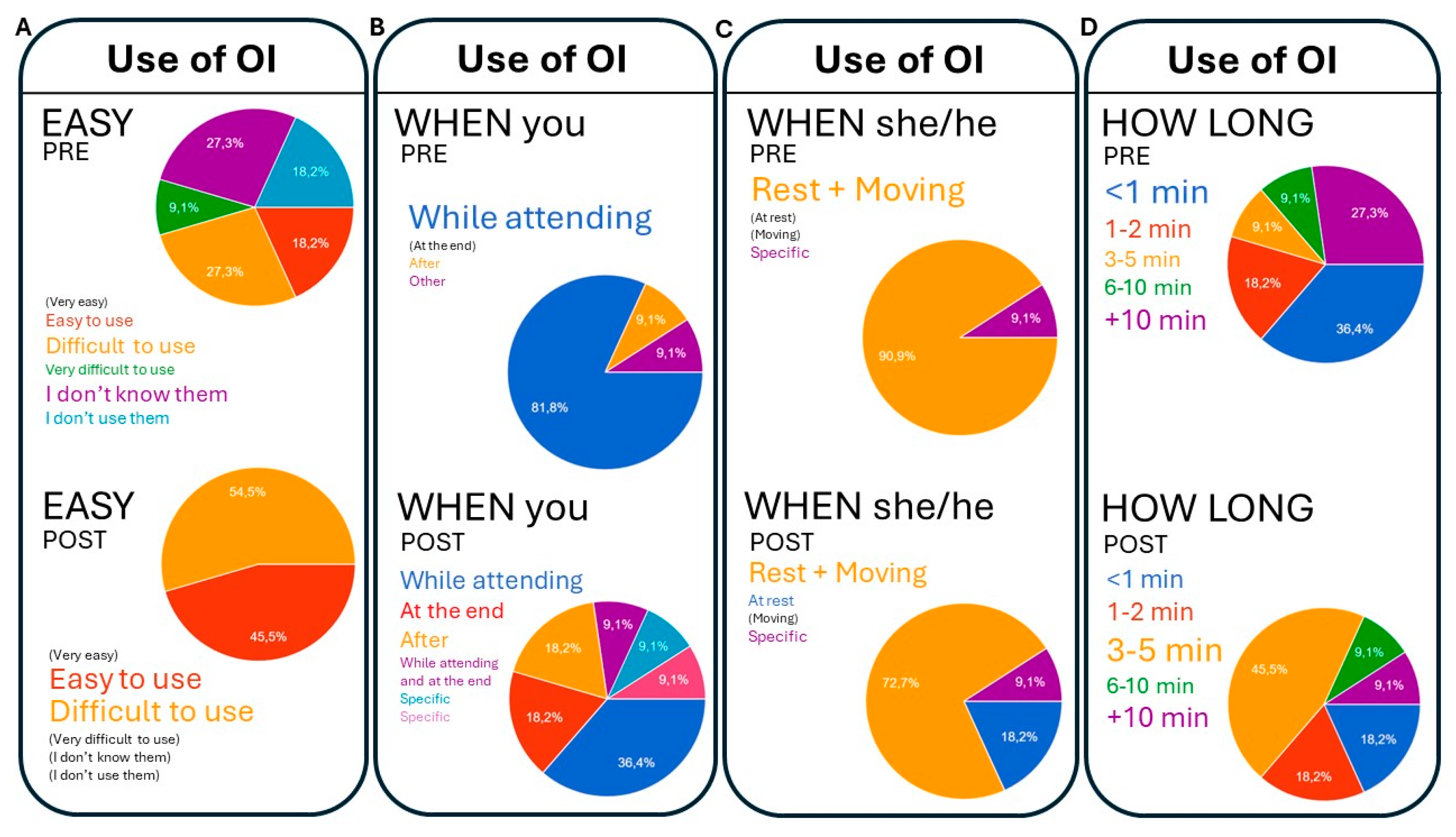

3.4.3. Feasibility and Conditioning Factors for the Use of Observational Instruments (Figure 3):

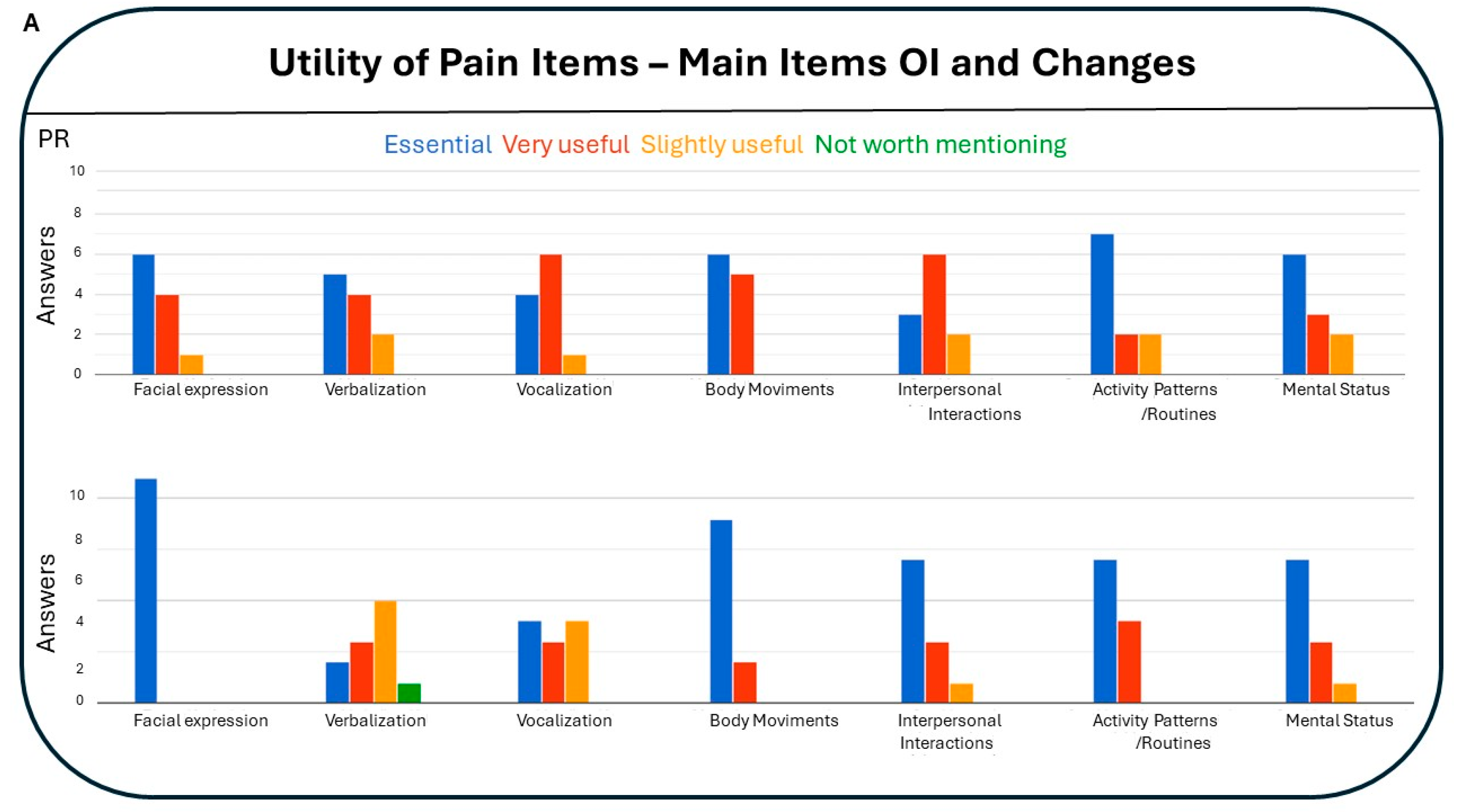

3.4.4. Utility of Pain Items: Main Items of Observational Instruments and Changes (Figure 4):

4. Discussion

- 1)

- The acquisition and unification of recognition criteria of the three elements of non-verbal communication on which the PAIC scale is based: Facial expressions, body movements and vocalizations.

- 2)

- The identification of these components in clinical cases that demonstrate their validity for differential diagnosis, overcoming confounding intrinsic/extrinsic factors (i.e., facial expression and posture in old age, environmental noises, etc).

- 3)

- The applicability in the clinical environment in a situation of rest and transfer (chair-to-chair or chair-to-bed displacements, for example).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vollset, S.E.; Ababneh, H.S.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasgholizadeh, R.; Abbasian, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Magied, A.H.A.A.A.; ElHafeez, S.A.; Abdelkader, A.; et al. Burden of disease scenarios for 204 countries and territories, 2022–2050: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2204–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Aflatoxins; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/ foodsafety/FSDigest_Aflatoxins_EN.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- World Health Organization. Long-term care for older people: package for universal health coverage. World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/376585 (accessed May 22 2024).

- Cole, C.S.; Carpenter, J.S.; Chen, C.X.; Blackburn, J.; Hickman, S.E. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Pain in Nursing Home Residents: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 1916–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viderman, D.; Tapinova, K.; Aubakirova, M.; Abdildin, Y.G. The Prevalence of Pain in Chronic Diseases: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Akkala, S.; Nayak, M.; Kotlo, A.; Poondla, N.; Raza, S.; Stankovich, J.; Antony, B. Impact of Pain on Activities of Daily Living in Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA). Geriatrics 2024, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwakhalen, S.M.; Koopmans, R.T.; Geels, P.J.; Berger, M.P.; Hamers, J.P. The prevalence of pain in nursing home residents with dementia measured using an observational pain scale. Eur. J. Pain 2009, 13, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwakhalen, S.M.; Koopmans, R.T.; Geels, P.J.; Berger, M.P.; Hamers, J.P. The prevalence of pain in nursing home residents with dementia measured using an observational pain scale. Eur. J. Pain 2009, 13, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntyselkä, P.; Hartikainen, S.; Louhivuori-Laako, K.; Sulkava, R. Effects of dementia on perceived daily pain in home-dwelling elderly people: a population-based study. Age and Ageing 2004, 33, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björk, S.; Juthberg, C.; Lindkvist, M.; Wimo, A.; Sandman, P.-O.; Winblad, B.; Edvardsson, D. Exploring the prevalence and variance of cognitive impairment, pain, neuropsychiatric symptoms and ADL dependency among persons living in nursing homes; a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helvik, A.-S.; Bergh, S.; Tevik, K. A systematic review of prevalence of pain in nursing home residents with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherder EJ, Bouma A. Is decreased use of analgesics in Alzheimer disease due to a change in the affective component of pain? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(3):171–174. [CrossRef]

- Achterberg, W.P.; Erdal, A.; Husebo, B.S.; Kunz, M.; Lautenbacher, S. Are Chronic Pain Patients with Dementia Being Undermedicated? J. Pain Res. 2021, ume 14, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.M. Pain relief at the end-of-life: a clinical guide. 2003, 99, 556–9. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, A.; Husebo, B.; Malcangio, M.; Staniland, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Aarsland, D.; Ballard, C. Assessment and treatment of pain in people with dementia. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 8, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, A.; Husebo, B.; Malcangio, M.; Staniland, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Aarsland, D.; Ballard, C. Assessment and treatment of pain in people with dementia. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 8, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achterberg, W.; Pieper, M.J.; van Dalen-Kok, A.H.; de Waal, M.W.; Husebo, B.S.; Lautenbacher, S.; Kunz, M.; Scherder, E.J.; Corbett, A. Pain management in patients with dementia. Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 1471–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, C.; Smith, J.; Corbett, A.; Husebo, B.; Aarsland, D. The role of pain treatment in managing the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2011, 17, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, C.; Smith, J.; Corbett, A.; Husebo, B.; Aarsland, D. The role of pain treatment in managing the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2011, 17, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nygaard, H.A.; Jarland, M. Are nursing home patients with dementia diagnosis at increased risk for inadequate pain treatment? Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briesacher, B.A.; Limcangco, M.R.; Simoni-Wastila, L.; Doshi, J.A.; Levens, S.R.; Shea, D.G.; Stuart, B. The Quality of Antipsychotic Drug Prescribing in Nursing Homes. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 1280–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briesacher, B.A.; Limcangco, M.R.; Simoni-Wastila, L.; Doshi, J.A.; Levens, S.R.; Shea, D.G.; Stuart, B. The Quality of Antipsychotic Drug Prescribing in Nursing Homes. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 1280–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipori, J.P.; Tu, E.; Shireman, T.I.; Gerlach, L.; Coe, A.B.; Ryskina, K.L. Factors Associated with Potentially Harmful Medication Prescribing in Nursing Homes: A Scoping Review. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 1589–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, A.; Husebo, B.S.; Achterberg, W.P.; Aarsland, D.; Erdal, A.; Flo, E. The importance of pain management in older people with dementia. Br. Med Bull. 2014, 111, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, A.; Achterberg, W.; Husebo, B.; Lobbezoo, F.; de Vet, H.; Kunz, M.; Strand, L.; Constantinou, M.; Tudose, C.; Kappesser, J.; et al. An international road map to improve pain assessment in people with impaired cognition: the development of the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC) meta-tool. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, M.; de Waal, M.W.M.; Achterberg, W.P.; Gimenez-Llort, L.; Lobbezoo, F.; Sampson, E.L.; van Dalen-Kok, A.H.; Defrin, R.; Invitto, S.; Konstantinovic, L.; et al. The Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition scale (PAIC15): A multidisciplinary and international approach to develop and test a meta-tool for pain assessment in impaired cognition, especially dementia. Eur. J. Pain 2019, 24, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Waal, M.W.M.; van Dalen-Kok, A.H.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Gimenez-Llort, L.; Konstantinovic, L.; de Tommaso, M.; Fischer, T.; Lukas, A.; Kunz, M.; Lautenbacher, S.; et al. Observational pain assessment in older persons with dementia in four countries: Observer agreement of items and factor structure of the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition. Eur. J. Pain 2019, 24, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, M.; Crutzen-Braaksma, P.; Giménez-Llort, L.; Invitto, S.; Villani, G.; Detommaso, M.; Petrini, L.; Vase, L.; Matthiesen, S.T.; Gottrup, H.; et al. Observing Pain in Individuals with Cognitive Impairment: A Pilot Comparison Attempt across Countries and across Different Types of Cognitive Impairment. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeta-Corral, R.; Defrin, R.; Pick, C.G.; Giménez-Llort, L. Tail-flick test response in 3×Tg-AD mice at early and advanced stages of disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 600, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañete, T.; Giménez-Llort, L. Preserved Thermal Pain in 3xTg-AD Mice With Increased Sensory-Discriminative Pain Sensitivity in Females but Affective-Emotional Dimension in Males as Early Sex-Specific AD-Phenotype Biomarkers. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defrin, R.; Amanzio, M.; de Tommaso, M.; Dimova, V.; Filipovic, S.; Finn, D.P.; Gimenez-Llort, L.; Invitto, S.; Jensen-Dahm, C.; Lautenbacher, S.; et al. Experimental pain processing in individuals with cognitive impairment. Pain 2015, 156, 1396–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwakhalen, S.; Docking, R.E.; Gnass, I.; Sirsch, E.; Stewart, C.; Allcock, N.; Schofield, P. Pain in older adults with dementia. Der Schmerz 2018, 32, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Llort, L.; Bernal, M.L.; Docking, R.; Muntsant-Soria, A.; Torres-Lista, V.; Bulbena, A.; Schofield, P.A. Pain in Older Adults With Dementia: A Survey in Spain. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global report on ageism. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- World Health Organization. Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, 2016–2021: Towards Ending Viral Hepatitis. 2016. Available online: http://apps. who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246177/1/WHO-HIV-2016.06-eng.pdf (accessed on).

- Liao, Y.-J.; Jao, Y.-L.; Berish, D.; Hin, A.S.; Wangi, K.; Kitko, L.; Mogle, J.; Boltz, M. A Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitators of Pain Management in Persons with Dementia. J. Pain 2023, 24, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravell, M.E. Pain-related palliative care challenges in people with advanced dementia call for education and practice development in all care settings. Évid. Based Nurs. 2017, 20, 118–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo-Coscollola, M.; Marquès-Graells, P. Classroom 2.0 Experiences and Building on the Use of ICT in Teaching. Comunicar 2011, 19, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, T. Hug, T. (2005). Micro learning and narration: Exploring possibilities of utilization of narrations and storytelling for the designing of “micro units” and didactical micro-learning arrangements. MiT4: The Work of Stories, Proceedings of the fourth Media in Transition conference, May 6-8, 2005, MIT, Cambridge (MA), USA.

- Hug, T. (2012). Microlearning. In: Seel, N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. [CrossRef]

- Molinuevo, B. (2017) Molinuevo, B. La comunicación no verbal en la relación médico-paciente [The non-verbal communication in the doctor-patient relationship]. Editorial UOC, ISBN: 9788491169734.

- Göller, P.J.; Reicherts, P.; Lautenbacher, S.; Kunz, M. How gender affects the decoding of facial expressions of pain. Scand. J. Pain 2022, 23, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, T.; Swede, M.J. Transforming Preprofessional Health Education Through Relationship-Centered Care and Narrative Medicine. Teach. Learn. Med. 2016, 31, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriana de la Olla, I. , Pajuelo González, L.M. & Giménez-Llort. Mejora de las competencias profesionales en la enfermería geriátrica en la detección y evaluación de dolor en pacientes con demencia [Improvement of professional skills in geriatric nursing in the detection and evaluation of pain in patients with dementia ] In: Conocimientos, investigación y prácticas en el campo de la salud [Knowledge, research and practices in the field of health]. Editor 1, Pérez-Fuentes, M.C., Editor 2, Gázquez, J.J., Editor 3, Molero, M.M., Editor 4, Simón, M.M., Editor 5, Martos, A. Editor 6, Barragán, A.B. Volumen II. Publisher: ASUNIVEP, Almería, Spain, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 933-938.

- Lautenbacher, S.; Sampson, E.L.; Pähl, S.; Kunz, M. Which Facial Descriptors Do Care Home Nurses Use to Infer Whether a Person with Dementia Is in Pain? Pain Med. 2016, 18, 2105–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lautenbacher, S.; Walz, A.L.; Kunz, M. Using observational facial descriptors to infer pain in persons with and without dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J.; Carstensen, L.L.; Pasupathi, M.; Tsai, J.; Skorpen, C.G.; Hsu, A.Y.C. Emotion and aging: Experience, expression, and control. Psychol. Aging 1997, 12, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatesta, C.Z.; Izard, C.E.; Culver, C.; Nicolich, M. Emotion communication skills in young, middle-aged, and older women. Psychol. Aging 1987, 2, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).