Submitted:

15 July 2024

Posted:

16 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

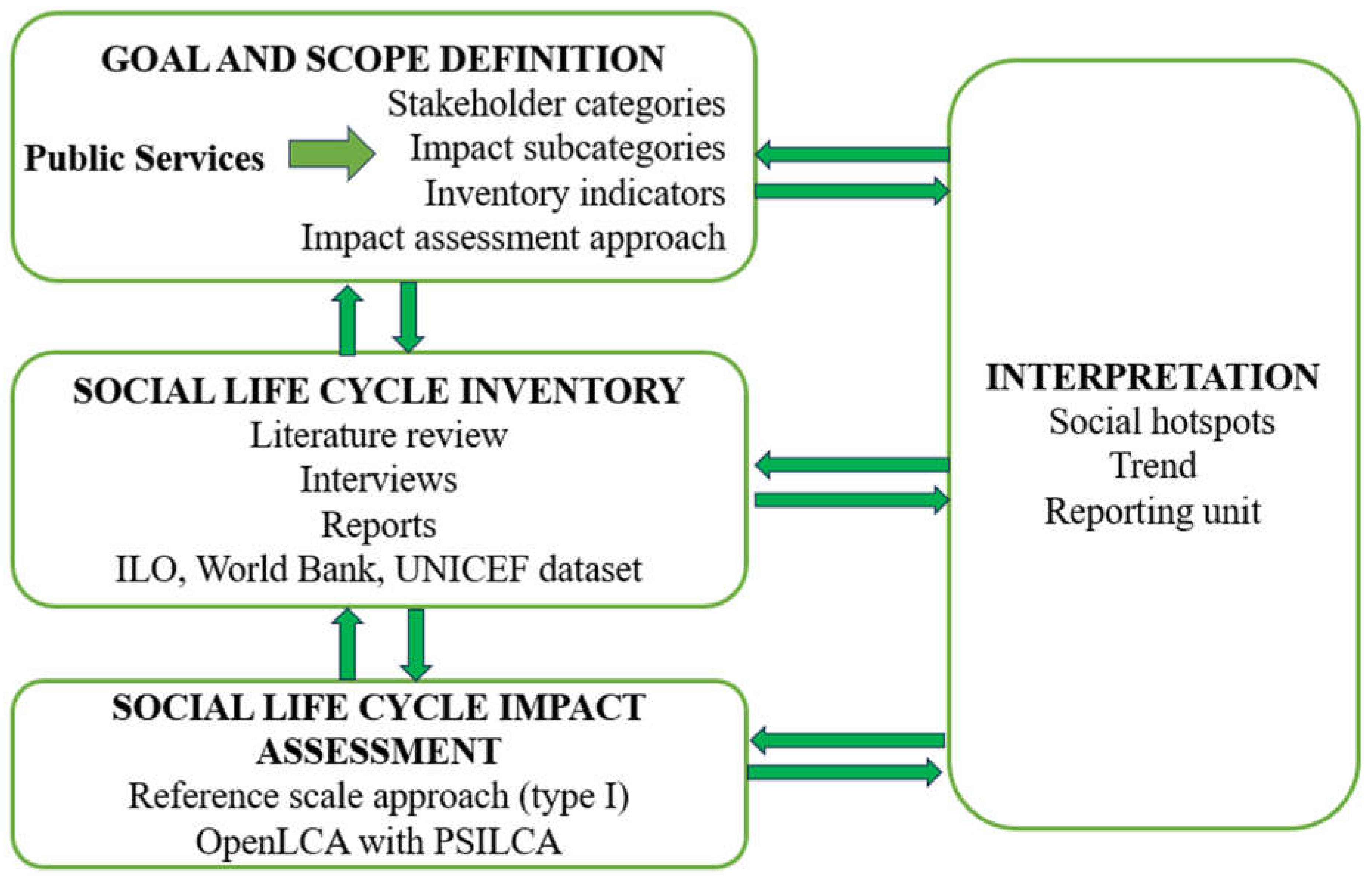

- Chapter 2 provides a detailed description of the methodology used in the process of developing a S-LCA research framework for public services. This includes an explanation of the research protocol, the software used, the data review process, and the analysis technique used.

- -

- Chapter 3 presents the qualitative and quantitative results obtained and the associated impact assessment methods. This also includes the stakeholder categories, impact subcategories, and indicators (hereafter referred to as components) identified for the case of public services.

- -

- Finally, Chapter 4 presents a discussion of the results obtained and the various conclusions on the research objectives as well as challenges or limitations identified in operationalizing S-LCA applications for public services.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Questions and Structure

2.2. Methodology

3. Results

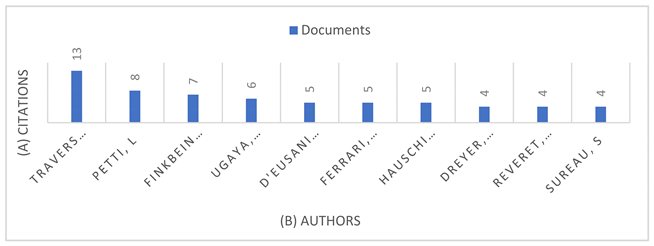

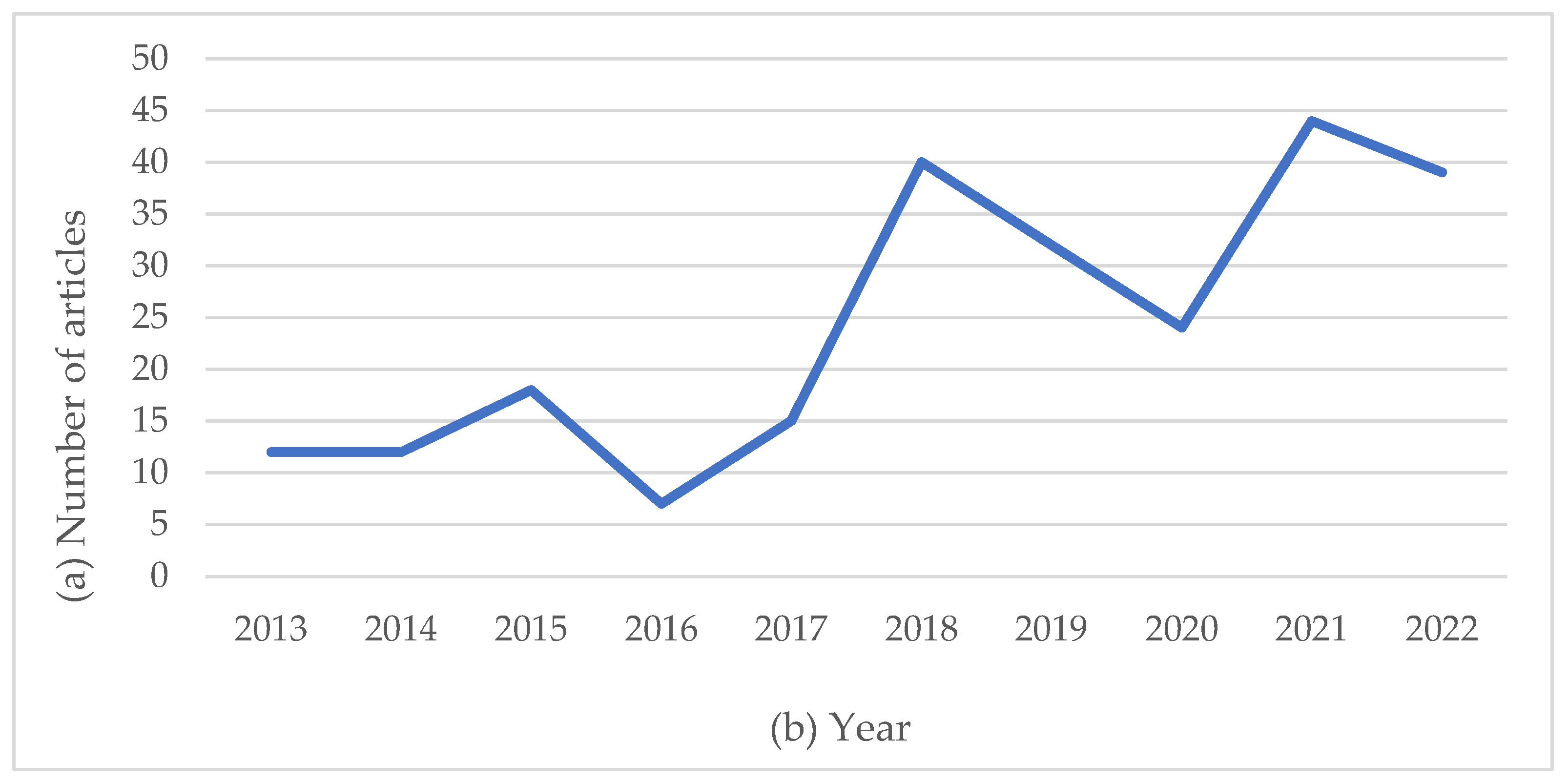

3.1. Evolution of the Scientific Production of S-LCA in Terms of the Publication, Sources, and Main Authors

3.2. Content Analysis

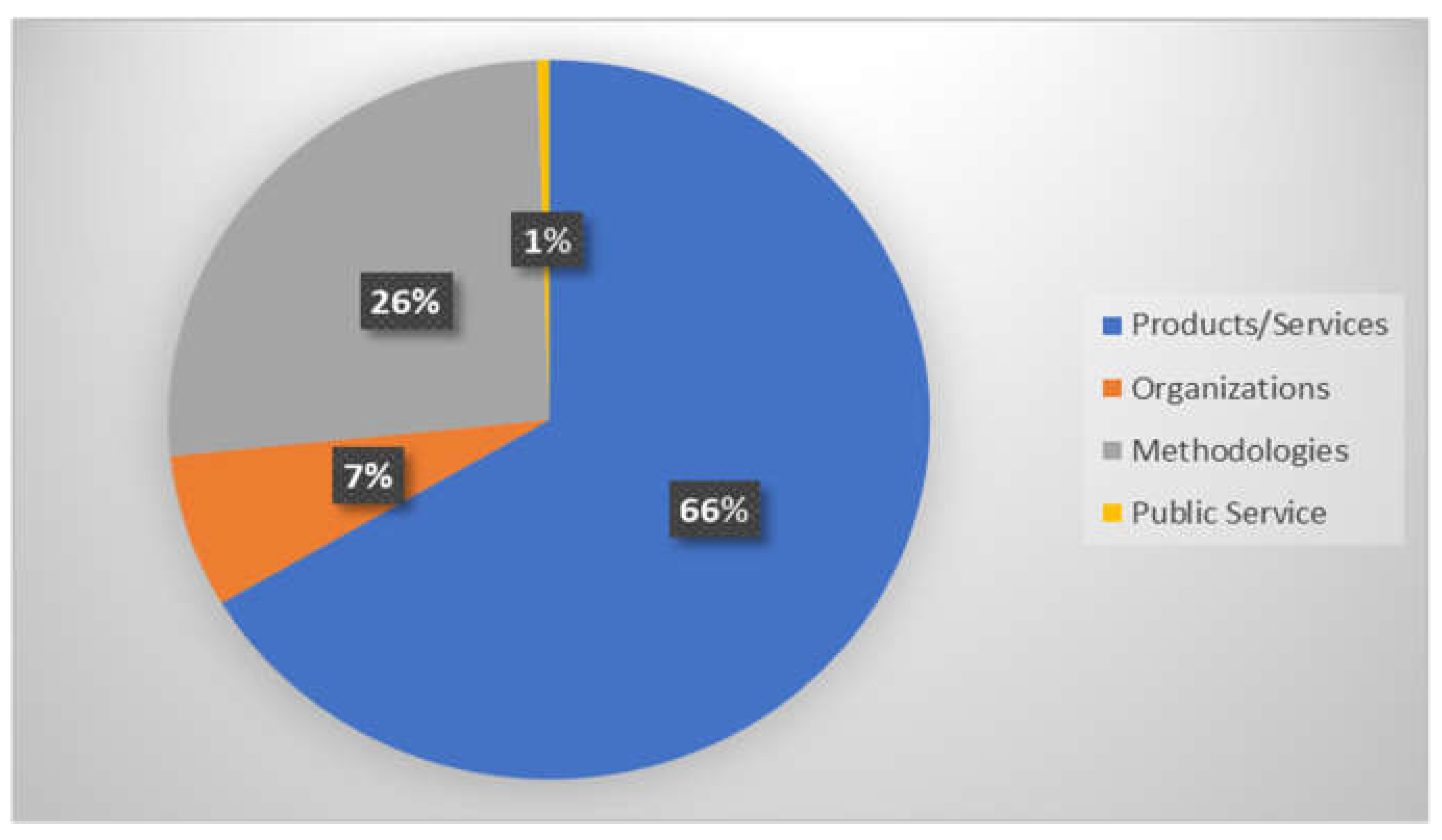

3.2.1. Research Topics and Objectives

3.3. Methodological Analysis

3.3.1. Approach to Selecting Stakeholder Categories

3.3.2. Approach to Selecting Impact Subcategories

3.3.3. Indicator Selection Approach

4. Discussion

4.1. Limit

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Assembly, U. G, Universal declaration of human rights, UN General Assembly, 1948, 302(2), 14-25.

- Cohen, É. , Champsaur, P., Service public, secteur public. La Documentation Française, France, 1997, (Vol. 3).

- Fournier, J, l’économie des besoins : une nouvelle approche du service public Odile Jacob, 2013.

- DE Vries, H.; Bekkers, V.; Tummers, L. Innovation in the public sector: A systematic review and future research agenda. Public Adm. 2015, 94, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.M.; Boyne, G.A. Public management reform and organizational performance: An empirical assessment of the U.K. Labour government's public service improvement strategy. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2006, 25, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dočekalová, M. Construction of corporate social performance indicators for Czech manufacturing industry. Acta Univ. Agric. et Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2013, 61, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odobaša, R.; Marošević, K. Expected contributions of the European corporate sustainability reporting directive (CSRD) to the sustainable development of the European Union. ECLIC 2023, 7, 593–612. [Google Scholar]

- Finkbeiner, M.; Schau, E.M.; Lehmann, A.; Traverso, M. Towards Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment. Sustainability 2010, 2, 3309–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, A.; Lai, L.C.H.; Hauschild, M.Z. Assessing the validity of impact pathways for child labour and well-being in social life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2009, 15, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompf, K.; Traverso, M.; Hetterich, J. Applying social life cycle assessment to evaluate the use phase of mobility services: a case study in Berlin. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme). Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products and Organizations 2020; Norris, C.B., Traverso, M., Neugebauer, S., Ekener, E., Schaubroeck, T., Garrido, S.R., Berger, M., Valdivia, S., Lehmann, A., Finkbeiner, M., et al., Eds.; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2020.

- UNEP. Methodological Sheets for Subcategories in Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA); Traverso, M.; Valdivia, S.; Luthin, A.; Roche, L.; Arcese, G.; Neugebauer, S.; Petti, L.; D’Eusanio, M.; Tragnone, B.M.; Mankaa, R.; et al. (Eds.) United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2021.

- Dubois-Iorgulescu, A.-M.; Saraiva, A.K.E.B.; Valle, R.; Rodrigues, L.M. How to define the system in social life cycle assessments? A critical review of the state of the art and identification of needed developments. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 23, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, A.; Bezama, A.; O’keeffe, S.; Thrän, D. Social life cycle assessment: in pursuit of a framework for assessing wood-based products from bioeconomy regions in Germany. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 23, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Valdivia, I.; Ferrari, A.M.; Settembre-Blundo, D.; García-Muiña, F.E. Social Life-Cycle Assessment: A Review by Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Life Cycle Initiative and Social Life Cycle Alliance, 2022 Pilot Projects on Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products and Organizations 2022 Traverso, M., Mankaa, M. N., Valdivia, S., Roche, L., Luthin, A., Gar rido, S. R., Neugebauer, S., (eds). Life Cycle Initiative.

- Petti, L.; Serreli, M.; Di Cesare, S. Systematic literature review in social life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesson, J. K. , & Lacey, F. M. How to do (or not to do) a critical literature review. Pharm. Educ 2006, 6(2), 139-148.

- Meho, L.I.; Yang, K. Impact of data sources on citation counts and rankings of LIS faculty: Web of science versus scopus and google scholar. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2007, 58, 2105–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homrich, A.S.; Galvão, G.; Abadia, L.G.; Carvalho, M.M. The circular economy umbrella: Trends and gaps on integrating pathways. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafa, W.; Sharaai, A.H.; Matthew, N.K.; Ho, S.A.J.; Akhundzada, N.A. Organizational Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (OLCSA) for a Higher Education Institution as an Organization: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morioka, S.N.; de Carvalho, M.M. A systematic literature review towards a conceptual framework for integrating sustainability performance into business. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camana, D.; Manzardo, A.; Toniolo, S.; Gallo, F.; Scipioni, A. Assessing environmental sustainability of local waste management policies in Italy from a circular economy perspective. An overview of existing tools. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macombe, C. , & Loeillet, D Social LCA in progress: 4th SocSem. In 4th International seminar in social LCA CIRAD 2014, (p. 207).

- Lu, Y.-T.; Lee, Y.-M.; Hong, C.-Y. Inventory Analysis and Social Life Cycle Assessment of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Waste-to-Energy Incineration in Taiwan. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erauskin-Tolosa, A.; Bueno, G.; Etxano, I.; Tamayo, U.; García, M.; de Blas, M.; Pérez-Iribarren, E.; Zuazo, I.; Torre-Pascual, E.; Akizu-Gardoki, O. Social organisational LCA for the academic activity of the University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 1648–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Eusanio, M. , Tragnone, B. M., & Petti, L. Social organizational life cycle assessment and social life cycle assessment: Different twins? Correlations from a case study. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2022, 27(1), 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryati, Z. , Subramaniam, V., Noorb, Z. Z., Loha, S. K., & Abd Aziza, A. Complementing social life cycle assessment to reach sustainable development goals-A case study from the Malaysian oil palm industry. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 83.

- Rafiaani, P.; Kuppens, T.; Thomassen, G.; Van Dael, M.; Azadi, H.; Lebailly, P.; Van Passel, S. A critical view on social performance assessment at company level: social life cycle analysis of an algae case. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 25, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, N.; Ustaoglu, E.; Benoit, C.; Norris, G.; Rosenbaum, E.; Vasta, A.; Sala, S. Social sustainability in trade and development policy. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 23, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillain, B.; Viana, L.R.; Lefeuvre, A.; Jacquemin, L.; Sonnemann, G. Social life cycle assessment framework for evaluation of potential job creation with an application in the French carbon fiber aeronautical recycling sector. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 1729–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Tejada, J.L.; Llera-Sastresa, E.; Scarpellini, S.; Morales-Pinzón, T. Social Organizational Life Cycle Assessment of Transport Services: Case Studies in Colombia, Spain, and Malaysia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Blanco, J.; Lehmann, A.; Chang, Y.-J.; Finkbeiner, M. Social organizational LCA (SOLCA)—a new approach for implementing social LCA. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 1586–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Questions | Sections | Method of analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Q1: What is the evolution of research activities in S-LCA in general and S-LCA of public services in particular? What is the trend in terms of a number of publications, scientific journals, and main authors? | 3.1 | Bibliometric analysis of combined data from Web of Science and Scopus, and use of the RAYYAN software |

| Q2: What are the specific research themes and objectives related to the S-LCA of products/services, organizations, and public services? | 3.2 | Qualitative data analysis |

| Q3: What are the different methodologies adopted in S-LCA and S-OLCA studies and that can be applied in the identified study for public services? | 3.3 | Qualitative analysis of identified articles on S-LCA and S-OLCA |

| Q4: What are the limitations and shortcomings of the studies in general and what is the potential of the S-LCA methodology for the public service? | 4 | Critical analysis of the results, emerging issues, and different perspectives. |

|

Keywords |

Number of studies in Web of Science | Number of studies in Scopus | Total number of studies | Number of duplicates found | Number of documents after extracting duplicates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-LCA | 159 | 163 | 322 | 266 | 189 |

| Social-LCA | 64 | 79 | 143 | 100 | 92 |

| S-LCA and Stakeholders | 64 | 69 | 133 | 104 | 81 |

| S-LCA and Case Studies | 81 | 79 | 160 | 134 | 93 |

| S-LCA of Products/services | 17 | 19 | 36 | 28 | 22 |

| Indicators of S-LCA | 83 | 78 | 161 | 132 | 95 |

| SO-LCA | 10 | 09 | 19 | 14 | 12 |

| Methodology of S-LCA | 80 | 76 | 156 | 124 | 94 |

| S-LCA and Public transport | 01 | 01 | 02 | 01 | 01 |

| S-LCA and Waste management/ municipal solid waste |

10 |

16 |

26 |

10 |

16 |

| S-LCA and water supply | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 |

| S-LCA and education | 01 | 01 | 02 | 01 | 01 |

| S-LCA and heath | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 |

| S-LCA and Public Service | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 |

|

TOTAL |

600 |

||||

| Final sample after extraction of duplicates and intruded documents | 222 | ||||

| Rank | Journal | No. Of documents |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LIFE CYCLE ASSESSMENT | 72 |

| 2 | SUSTAINABILITY | 26 |

| 3 | JOURNAL OF CLEANER PRODUCTION | 23 |

| 4 | RESOURCES-BASEL | 7 |

| 5 | SUSTAINABLE PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION | 6 |

| 6 | JOURNAL OF INDUSTRIAL ECOLOGY | 6 |

| 7 | RESOURCES CONSERVATION AND RECYCLING | 3 |

| 8 | SOCIAL LIFE CYCLE ASSESSMENT | 3 |

| 9 | CLEAN TECHNOLOGIES AND ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY | 2 |

| 10 | CHEMICAL ENGINEERING TRANSACTIONS | 2 |

| Nº | Authors | Year | Title | Objective | Journal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Gompf K et al. [10] | 2022 | Applying Social Life Cycle Assessment to Evaluate the Use Phase of Mobility Services: A Case Study in Berlin | Analyze the social impacts of the use phase of mobility services in a holistic manner, considering both positive and negative impacts | INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LIFE CYCLE ASSESSMENT |

|

2 |

Lu, Y.-T et al. [25] |

2017 | Inventory analysis and social life cycle assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from waste-to-energy incineration in Taiwan | Identify or raise key issues to be promoted for WtE incineration plants due to existing management systems and complex issues mixed with GHG, energy, and solid waste treatment. |

SUSTAINABILITY |

|

3 |

Erauskin-Tolosa, A et al. [26] | 2022 | Social organizational LCA for the academic activity of the University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU | Estimate the social footprint of a higher education institution (HEI) and its potential contribution to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) under the life cycle assessment (LCA) perspective | INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LIFE CYCLE ASSESSMENT |

|

4 |

D’Eusanio, M et al. [27] | 2022 | Social organizational life cycle assessment and social life cycle assessment: different twins? correlations from a case study | Attempt to implement SO-LCA and correlation analysis between social life cycle assessment (S-LCA) and SO-LCA | INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LIFE CYCLE ASSESSMENT |

|

5 |

Haryati, Z et al. [28] | 2021 | Complementing social life cycle assessment to reach sustainable development goals - A case study from the Malaysian oil palm industry | Coping with the social impacts associated with the oil palm industry is through the social life cycle evaluation (ACV-S) | CHEMICAL ENGINEERING TRANSACTIONS |

|

6 |

Rafiaani, P et al. [29] | 2020 | A critical view on social performance assessment at company level: social life cycle analysis of an algae case | Assess the social impacts of a company working on algae production systems in Belgium through social life cycle analysis (SLCA | INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LIFE CYCLE ASSESSMENT |

|

7 |

Pelletier, N et al. [30] | 2018 | Social sustainability in trade and development policy | Assess the social risks associated with trade-based consumption in EU Member States using a life-cycle approach versus a non-life-cycle approach | INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LIFE CYCLE ASSESSMENT |

|

8 |

Pillain, B et al. [31] | 2019 |

Social life cycle assessment framework for evaluation of potential job creation with an application in the French carbon fiber aeronautical recycling sector | Bringing in a significant amount of carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP) products in the coming years at the end of their life cycle | INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LIFE CYCLE |

|

9 |

Osorio-Tejada, JL et al. [32] | 2022 | Social organizational life cycle assessment of transport services: case studies in Colombia, Spain, and Malaysia | Analyze the social performance of companies involved in the supply chain of road transport companies located in different contexts such as Latin America, Europe, and Asia. | SUSTAINABILITY |

|

10 |

Martinez-Blanco, J et al. [33] | 2015 | Social Organizational LCA (SOLCA) a new approach for implementing social LCA | Propose a new organizational perspective to energize the SLCA - the social organizational LCA (SOLCA) | INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LIFE CYCLE ASSESSMENT |

| Title & Authors | Type of impact evaluation | Stakeholders’ categories identified | sub-categories identified | Indicators identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applying social life cycle assessment to evaluate the use phase of mobility services: a case study in Berlin (Gompf, K et al. 2022) | Reference scale approach (type I) | 5 | 28 |

39 |

| Inventory Analysis and Social Life Cycle Assessment of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Waste-to-Energy Incineration in Taiwan (Lu, Y.-T et al. 2017) | Risk assessments: Methods from the 2006 IPCC Guidelines to GHG |

8 | 9 |

18 |

| Social organizational LCA for the academic activity of the University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU (Erauskin-Tolosa, A et al. 2021) | Risk assessments: PSILCA-based Soca add-on for the Ecoinvent v3.3 database | 8 |

21 | 41 |

| Social Organizational Life Cycle Assessment and Social Life Cycle Assessment: Different Twins? Correlations from a case study (D’Eusanio, M et al. 2022) | Reference scale approach (type I) | 4 | 21 | 32 |

| Complementing social life cycle assessment to reach sustainable development goals - A case Study from the Malaysian oil palm industry (Haryati, Z et al. 2022) | Reference scale approach (type I) with performance reference point (PRP) approach. | 9 | 16 | 17 |

| A critical view on social performance assessment at company level: social life cycle analysis of an algae case (Rafiaani, P et al. 2020) | Performance reference points (PRPs) method | 3 | 10 | 10 |

| Social Sustainability in Trade and Development Policy (Pelletier, N et al. 2018) | Risk assessments: Eurostat ComEx import data at the HS06 level, Global Trade Analysis Project, sector codes, Social Hotspots Database (SHDB) | 5 | 10 | 4 |

| Social life cycle assessment framework for evaluation of potential job creation with an application in the French carbon fiber aeronautical recycling sector (Pillain, B et al. 2019) | Risk assessments: Social Hotspots Database (SHDB) | 8 | 2 | 8 |

| Social Organizational Life Cycle Assessment of Transport Services: Case Studies in Colombia, Spain, and Malaysia (Osorio-Tejada, JL et al. 2022) | Reference scale approach (type I) | 7 | 26 | 8 |

| Social organizational LCA (SOLCA)-a new approach for implementing social LCA (Martinez-Blanco, J et al. 2015) | Performance reference points (PRPs) method | 5 | 3 |

17 |

| Common stakeholders categories | Different stakeholders categories | Stakeholders’ categories that can be used for public services |

|---|---|---|

| Local Communities, Consumers, Workers, Value Chain Actors, Society, Governmental Authorities, Producers, Suppliers, Ngos, Investors, Employees | Environmental Organizations, Waste-To-Energy Incineration Industry, International Organizations, Transport Service Providers, Shareholders, Commuters & Passengers, Private Sector Companies, Regulators, Citizens, Companies, Manufacturers of Transport-Related Goods and Services, Business Partners, Faculty Members Students, Administrative Staff, Researchers, And Academics. | Local Communities, Consumers, Workers, Society, Governmental Authorities, Producers, Suppliers, NGOs, Investors, Employees, International Organizations, Transport Service Providers, Shareholders, Citizens, Companies, Regulators, and Business Partners. |

| Common impact subcategories | Different impact subcategories | Impact Subcategories that can be used for public services |

|---|---|---|

| 28 such as Local employment, community engagement, Safety, Feedback mechanism, Fair salary, discrimination, Child labor, Freedom of association and collective bargaining, forced labor, fair competition, etc. | 46 such as public space, air quality, Noise pollution, Space occupancy, consumer Accessibility, Convenience, Inclusiveness, Affordability, Privacy, Work-life balance, Supplier relationships, Society Health, Tax income, urban development, etc. | 74 such as Local employment, community engagement, Safety, Feedback mechanism, Fair salary, discrimination, Child labor, Freedom of association and collective bargaining, forced labor, fair competition, Intellectual property rights, Promoting social responsibility, contribution to economic development, Health, and safety, Social benefits, access to immaterial resources, access to material resources, Safe and healthy living conditions, Migration, fair competition, Corruption, Equal Opportunities/Discrimination, Secure Living Conditions, etc. |

| Common Indicators | Different Indicators | Indicators that can be used for public services |

|---|---|---|

|

34 such as Minimum wage paid, Minimum wage rate, late wage payment, paid below, schedule of wage paid, working hours, Average weekly working hour, working hours per week, Weekly hours of work per employee, Child labor female, Child labor male, Child labor total, frequency of forced labor, goods produced by forced, labor Presence of social benefits, etc. |

152 such as Green and open space per capita, the Emission intensity of NOx, Emission intensity of PM10, Emission intensity of PM2.5, Emission intensity of SO2, Percentage of employees hired, Percentage of employees hired locally, Noise pollution greater than 65 dB, Average emissions of noise, Degree of population participation, Infrastructure efficiency, Infrastructure space occupancy, Space occupancy about green and open space, Number of transport points Number of passengers, Fatal and non-fatal traffic accidents, Punctuality of delivery, etc. | 178 such as Minimum wage paid, Minimum wage rate, late wage payment, paid below, schedule of wage paid, working hours, Average weekly working hour, Working hours per week, Weekly hours of work per employee, Child labor female, Child labor male, Child labor total, frequency of forced labor, goods produced by forced, labor Presence of social benefits, Formal policy of safety and health, the average number of workdays lost per worker per year, Rate of female to male employees, Health and safety policies and records, culture and heritage, human rights, education and training, community involvement, labor rights and equal opportunities, greenhouse gas emissions, waste generation, Water consumption, etc. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).