1. Introduction

Despite material abundance, modern people experience physical fatigue and stress and strive to improve their quality of life and pursue happiness through mental health enhancement. Various prior studies [

2,

3,

4] have indicated that experiential consumption provides greater happiness to consumers compared to material consumption. Even before the novel coronavirus 2019 pandemic, studies consistently emphasized the importance of offering a higher-level experience to meet travelers’ rapidly changing tourism desires [

5,

6,

7]. Following the pandemic, there has been an increase in travelers seeking psychological stability and happiness through daily trips and various experiences. For instance, according to the 2023 and 2024 consumer trends reports issued by the global market research agency Euromonitor International, consumers sought to escape the mundanity and tediousness of daily life to alleviate stress and anxiety (delightful distractions), with personal happiness and well-being emerging as top priorities in the post-COVID era (the thrivers) and a growing trend toward seeking joy in the “here and now”.

Recent tourism studies have emphasized the importance of experience and have attempted to understand it from various perspectives. Specifically, the relationship between experience and happiness has attracted significant attention from many researchers [

5,

8,

9]. Csikszentmihalyi [

10] viewed life as a series of experiences involving seeing, hearing, tasting, feeling, and smelling through the senses, as well as experiencing emotions, thoughts, actions, and relationships with people and things, which aligns with Schmitt’s [

1] strategic experiential modules (SEMs) of sense, feel, think, act, and relate.

While traditional marketing viewed consumers as rational decision-makers preferring functional features and benefits, Schmitt saw consumers as rational and emotional beings interested in sensory and enjoyable experiences. Specifically, he emphasized the importance of a holistic experience rather than the combination or superiority of individual experiential elements. Schmitt’s experiential marketing strategy is distinct in that it provides customers with an experience that integrates sensory, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and relational factors.

While everyone pursues happiness, the experience of happiness varies for each individual. Differences in experiences arise because the subjects of the experiences differ, and the basis for experiencing and evaluating life differently stems from mental differences [

11]. Prior studies have shown a lack of interest and understanding in the role of organically connecting and reinforcing the relationship between experience and happiness. Wiking and Wiking [

12] emphasized that happiness exists even in close relationships with others and that it is important to pay attention to the present moment to feel happiness in escapism. This aligns with Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of flow, where one can experience happiness by achieving a state of inner order and well-being through escaping the routine, a state where time seems to pass unnoticed owing to focusing one’s thoughts and mind on a specific task [

13].

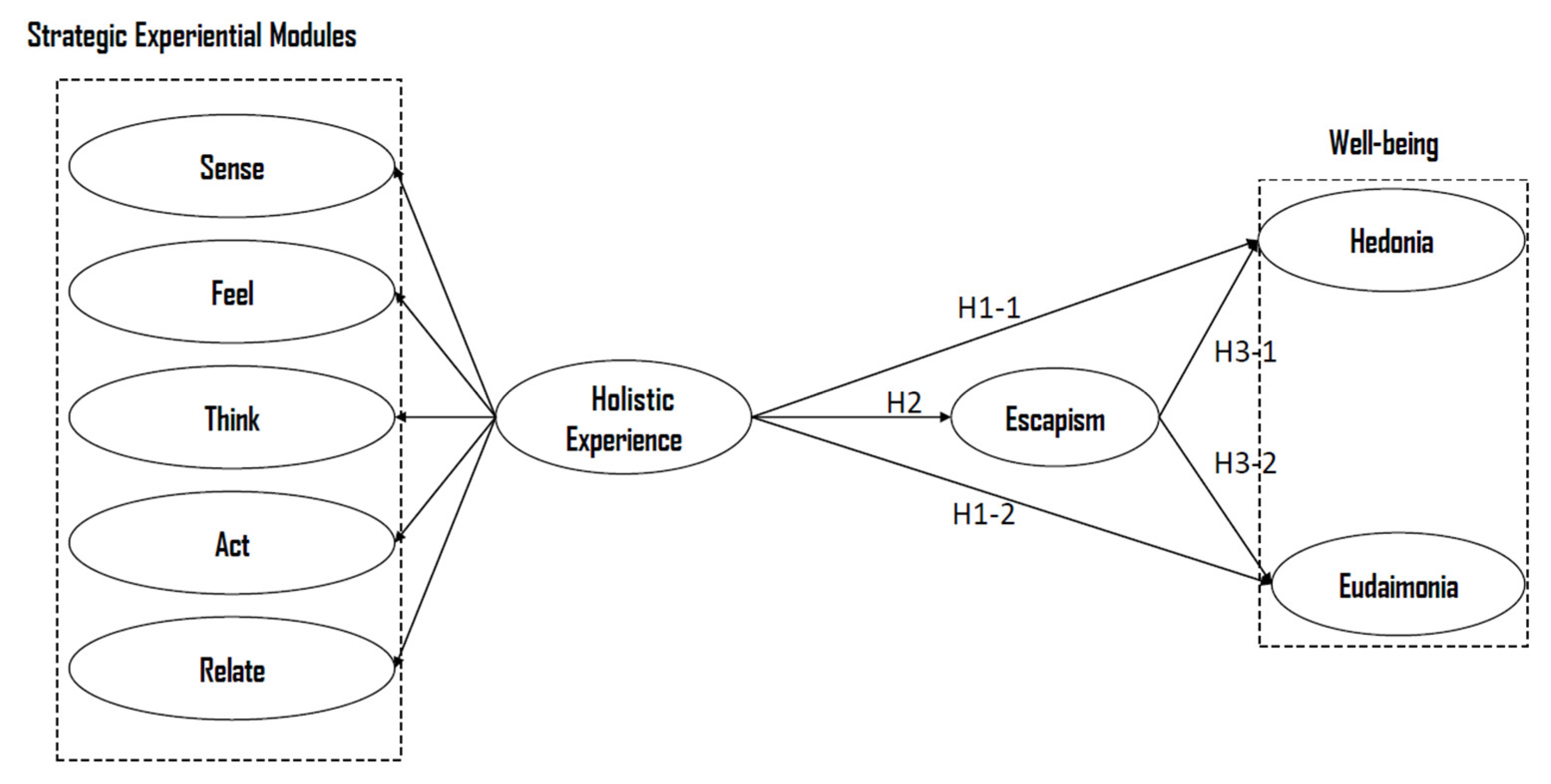

Accordingly, this study aims to expand on theory in the field of tourism by empirically examining the mediating role of escapism from the routine in the relationship between experience and travelers’ well-being. Additionally, instead of emphasizing the economic value and individual superiority of experience, as most prior studies have done, this study seeks to confirm the importance of holistic experience (i.e., sense, feel, think, act, and relate), as proposed by Schmitt’s [

1] SEM theory. By verifying the mediating role of escaping the routine in achieving well-being through experiences that make everyday life a journey and travel a part of escapism, this study aims to contribute to the establishment of a mature and desirable travel culture where travelers are the main subjects.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Holistic Experience and Well-being

Everyone pursues happiness, but the definition of happiness varies across academic fields and researchers. Happiness has been described using various terms such as well-being, subjective well-being, subjective quality of life, and life satisfaction, which are often used interchangeably [

14]. In philosophy, Aristotle argued that the ultimate goal is to experience happiness, stating that the aim of work is leisure, and a leisurely life equates to happiness. In psychology, individual life satisfaction or happiness is defined as subjective, emotional, and psychological quality of life, well-being, and contentment, with well-being encompassing life satisfaction and happiness from a macro perspective [

15]. Well-being is approached through the concepts of hedonia and eudaimonia, which, as distinguished by Aristotle, involve not only simple emotional pleasure but also striving for greater meaning and self-realization in life [

16].

Csikszentmihalyi [

10] emphasized that experience occurs over time and that one’s quality of life is determined by its content. Schmitt [

1] explained experience in his book “Experiential Marketing” as being composed of five modules: sensory, emotional, cognitive, relational, and behavioral, termed SEM. Unlike traditional marketing, which views consumers as rational decision-makers, Schmitt considers consumers to be emotional beings interested in enjoyable experiences. Experience is interconnected organically, forming holistic experiences (rather than isolated ones) in which the five modules are integrally connected. Son Seon-Mi [

17] agreed that experience involves interactions with various elements, leading to emotional and knowledge gains through seeing, touching, hearing, and feeling.

In tourism studies, various experiential research based on the SEM theory has been conducted. However, research on cultural heritage experience is relatively lacking, with most previous studies focusing on multidimensional experience without confirming the effects of holistic experience, as emphasized by Schmitt [

18]. Most research has been conducted from the perspective of tourist destinations or suppliers, with insufficient discussion focused on enjoyment and true happiness from the travelers’ perspective [

19]. Therefore, this study aimed to apply Schmitt’s SEM theory to identify to what extent holistic experience (sensory, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and relational) enhances travelers’ well-being compared to individual experience. Previous studies empirically demonstrating the close relationship between well-being and experience [

2,

6,

20] showed that various experiences increasing enjoyment from the hedonic perspective. On the other hand, some studies have identified a link between experience and eudaimonia, suggesting that interactions with others and self-reflection during travel contribute to living a self-realized life [

21]. Unlike previous studies that focused on one aspect of well-being, this study argues for an integrated composition that includes temporary pleasure (hedonia) and greater meaning, self-realization, and subjective life satisfaction (eudaimonia) [

9,

22,

23,

24]. Only a few studies applying Schmitt’s holistic experiential modules theory [

18] have incorporated interconnected modules of sensory, emotional, cognitive, relational, and behavioral experience. Therefore, this study seeks to verify the impact of Schmitt’s holistic experience on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being rather than a multidimensional approach to experience [

21,

25] and proposes the following hypotheses:

H1 Holistic experience has a significant positive impact on well-being.

H1-1 Holistic experience has a significant positive impact on hedonia.

H1-2 Holistic experience has a significant positive impact on eudaimonia.

2.2. Holistic Experience and Escapism

In “The Experience Economy,” Pine and Gilmore [

26] mentioned that escapism experienced by consumers through products or environments presupposes active participation and immersion. Csikszentmihalyi defined immersion as a state in which a person’s mind and thoughts are fully concentrated on a particular activity, arguing that this enables an individual to attain inner order and well-being, which he equates with happiness [

13]. This concept is akin to the story in “Zhuangzi”, where the butcher, Pao Ding, experiences happiness by being completely absorbed in the act of cutting up an ox [

27]. However, while Csikszentmihalyi views immersion itself as a state of happiness, Zhuangzi contends that happiness is felt after one returns to a normal state of consciousness after immersion.

In modern society, despite enjoying material abundance in a highly industrialized environment, people often feel alienated and powerless, seeking to recover their sense of self through escapism [

28]. Escapism is defined as actions taken to escape from the complexity and monotony of life to find pleasure and relaxation [

29,

30].

Based on previous studies, we define escapism as breaking away from routine tasks, stress, fatigue, frustration, boredom, and ennui. We discuss the mediating effect of active participation and immersion in the sensory, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and relational experience of travel on hedonic well-being through the novelty of experiencing new environments that differ from everyday life.

Escapism is a positive deviant behavior aimed at satisfying the desire to escape from the complexity and monotony of life to seek enjoyment and relaxation [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. In the field of tourism, experiential activities have been shown to positively impact escapism through physical and voluntary activities [

33,

34]. Particularly, it is argued that experiencing festivals allows individuals to find new vitality and return to their daily lives with renewed vigor [

31,

35]. Additionally, experiences have been found to reduce the perception of everyday worries and anxieties by exposing individuals to new environments [

31,

34].

Based on these previous research findings, this study hypothesizes a significant positive relationship between holistic experience and escapism and aims to verify this through the following hypothesis:

2.3. Escapism and Well-being

Research indicates that travelers’ escapism behaviors are often driven by a desire to pursue hedonic pleasures [

9,

36]. However, other findings suggest that escaping from daily routines through new experiences can enhance positive emotions and overall life satisfaction [

37]. Additionally, escapism has been shown to reduce stress, increase positive emotions, and enrich life with greater diversity [

38]. Engaging positively in desired activities and immersing in leisure activities as a form of escapism can be seen as opportunities for self-development and self-expansion [

39]).

Based on these previous research findings, this study hypothesizes the following regarding the impact of escapism from experience on well-being:

H3 Holistic escapism has a significant positive impact on well-being.

H3-1 Holistic escapism from experience has a significant positive impact on hedonia.

H3-2 Escapism from experience has a significant positive impact on eudaimonia.

3. Method

3.1. Research Model

Figure 1 presents the research framework.

3.2. Data Collection

A cultural heritage experience involves visiting historically and culturally significant places or objects to enjoy related experiences [

40]. In this study, we applied mindfulness, a Buddhist practice, to survey visitors at Buddhist cultural heritage sites. The survey was conducted at the exits of major historical and cultural sites in Gyeongju City, South Korea, specifically Bulguksa Temple, Seokguram Groffo , and Bunhwangsa Temple. The survey period lasted 11 days (April 13 to April 23, 2023), and a total of 520 questionnaires were collected. After excluding 11 questionnaires with duplicate responses or missing information, 509 questionnaires were used for the final analysis. Reliability and validity were confirmed through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), Cronbach’s alpha, and discriminant validity analysis (DVA). Path analysis was used to test the research hypotheses, bootstrapping indirect effect analysis was used for mediating effects, and multi-group analysis was used for moderating effects.

3.3. Research Instrument

In this study, drawing from Schmitt’s [

1] research and subsequent studies by Yoon Seol-Min et al. [

21], Oh Min-Jee et al. [

41], and Park et al. [

42], we utilized the SEM theory to formulate four items each for sensory, emotional, cognitive e, and relational experience. Well-being is bifurcated into hedonia and eudaimonia. Referencing research by Kim Myung-Sun [

43], Lengieza and Swim [

44], hedonia was developed using three items, while eudaimonia was constructed with a total of seven items. Based on the works of Pine and Gilmore [

26], Hosany and Witham [

45], and Oh et al. [

46], escapism was represented through a total of four items. All variables were assessed utilizing a 5-point Likert scale, I for strongly disasree and 5 for strongly agree [

Table 1].

3.4. Data Analysis

The questionnaire was based on prior research and consisted of 20 items divided into five factors of travel experience: sense, feel, think, act, and relate [

1,

19,

21,

25,

41,

42,

47,

48] with four items for each factor. Additionally, well-being was measured using three sub-variables: hedonia (4 items) [

9,

43,

44], eudaimonia [

9,

43,

44,

49] (7 items), and escapism from routine (4 items) [

25,

26,

45,

50]. The questionnaire was reviewed and revised twice by three tourism experts and two graduate students.

To test the research hypotheses, we conducted an analysis of reliability and validity using CFA and correlation analysis. We further evaluated the research hypotheses and questions by comparing SEMs, performing path analysis, and employing bootstrap indirect effect analysis. Additionally, we analyzed differences between tourists in the daily and non-daily living spheres and used multigraph analysis.

The empirical analysis was conducted using SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 26.0. Descriptive and frequency analyses were performed to identify sample’s characteristics, and reliability and validity were confirmed through CFA, DVA, and Cronbach’s alpha. Path analysis was used to test the research hypotheses, bootstrapping indirect effect analysis was used for the mediating effects, and multi-group analysis was used for the moderating effects.

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Demographics

The study comprised a sample of 509 participants. In terms of gender distribution, 60.9% were females, 38.7% were males, and 0.4% identified in other categories, signifying a larger number of female travelers. Regarding marital status, 66% were married, 32.8% were unmarried, and 1.2% identified as other. Delving into the age distribution, the largest group was the 40–49 age bracket at 32.5%, followed by the 30–39 group at 22.6%, the 50–59 group at 18.7%, the 20–29 group at 14.2%, those aged 60 or older at 10%, and 2% fell into other age categories. Regarding residence, a majority (50.8%) hailed from regions outside of the cities of Daegu, Gyeongbuk, and Ulsan, while 34% resided within this area. On the religious front, 49.8% professed no religious affiliation, 32.9% were Buddhists, and 17.3% adhered to other religious denominations.

4.2. Traveler Type

The choice of companion varied among travelers going on cultural heritage trips. A significant number (48.1%) traveled with family or relatives; 31.4% with friends or lovers; 11.2% with social groups, clubs, or work colleagues; and 7.5% preferred to travel alone. As for the nature of these trips, 54.6% were group outdoor trips involving two or more individuals, 28.7% were solo outdoor trips, 10.6% took part in group indoor trips, and 5.1% engaged in individual indoor trips. Regarding the frequency of visits to Gyeongju City’s cultural and historical sites in the past three years, 43.2% were first-time visitors. Those who made 2–3 visits constituted 27.3%, those who made 4–5 visits accounted for 8.4%, more than once a year were 6.3%, 6–10 visits made up 6.1%, and 4.3% visited monthly or more. The remaining 1.6% fell into other categories of visit frequencies.

4.3. Reliability and Validity

We conducted CFA on the measurement items. To gauge the derived measurement model’s adequacy, a range of fit and modification indices — including factor loadings, standardized factor loadings, t-values, p-values, and fit indices — were studied. A holistic evaluation of the model employed absolute fit indices (e.g., χ², CMIN/df (targeted below 3.00)) and incremental fit indices, specifically the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) (targeted above .900) and comparative fit index (CFI) (targeted above .900), benchmarked against an independent model. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was also analyzed for the parsimonious fit index, with a target of less than .080, which indicates the model’s simplicity [

51]. The outcomes for the CFA fit were as follows: χ²=1964.545 (df=739), CMIN/df=2.658, p<.000, CFI=.937, TLI=.931, RMSEA=.057, indicating a satisfactory model fit. Diving deeper into convergent validity, we found that the average variance extracted (AVE) was above .747. Convergent validity measures the correlation between items gauging the same concept, with higher correlations suggesting robust agreement [

51,

52]. We employed three techniques to affirm convergent validity: factor loadings, composite construct reliability (CCR), and AVE [

53]. Acceptable benchmarks include standardized factor loadings and AVE values both exceeding .50. In this research, concept reliability was beyond .877 and AVE surpassed .616. To further ensure the validity of findings, we verified the reliability of the measurement items, which speaks to the consistency of results on repeated measurements and was assessed using Cronbach’s α coefficient. In the context of social sciences, a Cronbach’s α surpassing .6 denotes reliability [

54]. Notably, the reliability coefficients for the elements of daily leisure activity experience, hedonia, eudaimonia, awareness, and escape from routine all exceeded .881, cementing their reliability.

Table 2 details the results.

The directionality of the hypotheses and the consistent relationships between latent factors were confirmed through a correlation analysis (CA). When there’s a positive correlation between the measurement tools of two latent factors, as affirmed in previous studies or logically accepted, these tools are deemed to possess construct validity [

51,

55]. Our CA results showed a positive causal connection between the factors, which aligns with the pre-set hypotheses about their inter-relationships. This supports the construct validity, as it is consistent with the hypothesized relationships. Discriminant validity was assessed by verifying that the AVE of each latent factor exceeds the squared correlation coefficient (∅) between latent factors [

56]. Given the arduousness of validating all variables, researchers typically select a pair of conceptually related or strongly correlated variables for this purpose [

53]. This method is favored as a higher inter-variable correlation often implies a greater likelihood of compromised discriminant validity. For the two highest correlated variables in this analysis (i.e., cultural heritage experience and cultural heritage travel activity experience) the squared correlation coefficient was calculated to be (.767)^2 = .588. This figure is overshadowed by the AVE values for sensory experience (AVE = .720), feel experience (AVE = .728), think experience (AVE = .640), act experience (AVE = .746), relate experience (AVE = .759), escapism (AVE = .727), hedonia (AVE = .792), and eudaimonia (AVE = .616). Hence, the data confirms the discriminant validity. This sets the stage for utilizing an SEM approach on the validated factors. Detailed results of this evaluation can be found in [

Table 3].

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

We delved into the interplay between cultural heritage experience, well-being, and escapism using SEM for hypothesis testing. The detailed outcomes, outlined in [

Table 4], underscore the statistical significance of all five proposed pathways. Measured against conventional standards for covariance structure analysis models, the indices, χ²= 1596.105 (df=546), CMIN/df=2.923, p<.000, CFI=.935, TLI=.930, and RMSEA=.062, indicate a commendable fit for the model. Delving deeper, cultural heritage experience exerted a noteworthy positive influence on both hedonia (β=.568, p<.001) and eudaimonia (β=.675, p<.001), affirming H1-3 and H1-4. Moreover, a marked positive relationship was found between cultural heritage travel experience and escapism (β=.562, p<.001), which supports H2-2. Escapism also positively impacted hedonia (β=.154, p<.001) and eudaimonia (β=.106, p< .017), confirming H3-3 and H3-4. These results collectively emphasize the profound relationships interlinking cultural heritage experience, well-being, and escapism.

4.5. Mediating Effect Analysis

In examining the relationships between cultural heritage experience, escapism, and hedonia, the bootstrapping results revealed an indirect effect coefficient of 0.084. This coefficient has a two-tailed significance level of 0.040, denoting statistical significance. Similarly, when evaluating the relationships between cultural heritage experience, escapism, and eudaimonia, the bootstrapping results showed an indirect effect coefficient of 0.062, with a two-tailed significance level of 0.001, which is also statistically significant. Based on these findings, H4-1 and H4-2 were accepted. The results suggest that as cultural heritage experience intensifies, both hedonia and eudaimonia act as mediators through escapism.

4.6. Multi-Group Analysis

When evaluating the goodness of fit indices for the unconstrained model, the following observations were made: the TLI is 0.887, the chi-squared (χ²) value stands at 2,634.800 with 1,100 degrees of freedom, the CFI is 0.896, and the RMSEA is 0.055. Meanwhile, for the measurement weights model, the TLI is 0.890, the χ² value is 2,661.242 with 1,127 degrees of freedom, the CFI is 0.896, and RMSEA remains at 0.055. These metrics suggest a satisfactory fit for both models.

Table 5 provides a detailed analysis of the results.

We executed a multiple-group analysis to discern variations in the standard path coefficients regarding the influence of cultural heritage experience on well-being in daily and non-daily living contexts. To ascertain the significance of these path differences between contexts, we used a multiple-group SEM analysis. The established thresholds for determining significance were as follows: for the p<.05 level, a critical ratio (CR) greater than ±1.96; for the p<.01 level, a CR greater than ±2.58; and for the p<.001 level, a CR exceeding ±3.30. In our research model, the path to hedonia within cultural heritage experience was significant for both the daily (p<.001) and non-daily living (p<.001) groups. However, with a path difference of -0.21 and a CR value of ±2.58, there was no statistical significance at the p<.01 level. Similarly, the path to eudemonia in cultural heritage experience was significant for both contexts (p<.001 for each). Still, with a path difference of -0.53 and the same CR value, there was no discernible statistical difference at the p<.01 level. When examining the path from escapism to hedonia in cultural heritage travel, both groups showed significance (p<.001 for each). However, a path difference of 1.453 and a CR value of ±2.58 suggests no statistical significance at p<.01. Finally, the path from escapism to eudemonia in cultural heritage travel was not statistically significant in either the daily (p<.001) or the non-daily living groups (p<.056). As detailed in Table 8, both groupings yielded CR values below the ±2.58 threshold, indicating no significant path difference between them.

Table 6 provides detailed analysis results.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In this research, we explored the mediating role of escapism to understand how cultural heritage experience impacts well-being. Analyzing data from 509 participants through SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 26.0, the findings showed that cultural heritage travel experience positively correlates with well-being and ha a robust relationship with escapism. Intriguingly, there was no discernible difference in how experience, escapism, and well-being interplay between travelers immersed in escapism spheres and those in non-daily living spheres. Three primary hypotheses emerged from the study. First, cultural heritage experience has a favorable influence on escapism, which aligns with the insights of Bai, Lin, and Jin [

57] and Kim [

43]. Second, these experiences positively affect well-being, a finding corroborated by studies such as Choi and Lee [

58] and Park and Shim [

59]. Third, escapism, in itself, enhances well-being, as noted by researchers such as Cho and An [

60]. Moreover, when delving deeper, it is evident that cultural heritage experience influences well-being with escapism acting as a mediator — a relationship supported by an array of research, including [

61], among others.

The validation of the connection between cultural heritage experience and well-being (as indicated by the adoption of H1) resonates with findings from various domestic and international studies. These studies, which are similar in context, corroborate our observations. However, where our research stands apart is in its nuanced application of Schmitt’s [

1] transformative module of experience, which encompasses the facets of sensory, affective, cognitive, active, and relational experience. By doing so, we critically examine the interplay between the well-being dimensions, hedonia, and eudaimonia. Furthermore, Schmitt’s [

1] module’s incorporation into tourism research is pivotal. It signifies a shift toward a more consumer-centric approach that transcends traditional metrics such as loyalty and revisit intention. This orientation becomes particularly salient in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. The emphasis post-pandemic has perceptibly tilted toward activities offering stress-relief and happiness. Consequently, travel activities, especially those set in familiar and secure environments as opposed to distant locales, have gained prominence. This trend underscores the rise of “everyday tourism” — a form characterized by cozy, secure sojourns in known spaces, highlighting small-scale, independent, and localized experience.

Reports from sources such as the Korea Health Promotion Institute [

62] highlight that the COVID-19 pandemic has adversely affected individuals’ well-being, with a notable surge in feelings of anxiety and depression underscoring the urgent need for a re-evaluation of the tourism sector. Instead of persisting with conventional strategies that prioritize quantitative metrics, such as the number of travelers or tourism revenue, there is a pressing need to emphasize policies that cater to enhancing individual well-being. This pivot will address the emergent mental health concerns while aligning tourism with the current zeitgeist.

6. Limitations and Future Research

One limitation of this study is its narrowed focus on the cultural heritage travel experience of visitors within a specific target area, leading to a somewhat constrained perspective on experience. This constraint underlines the importance of diversifying future research. Subsequent studies should categorize participants by the type of experiential programs, delving deeper into the psychological shifts associated with each distinct experience. Furthermore, recognizing that interests and emotional responses can fluctuate based on age, it becomes imperative for future research endeavors to target a broader age demographic, which will enable a more comprehensive understanding of the variances across different age groups.

Author Contributions

Gamanamu: writing—original draft, investigation, Analysis. Jeong-Ja-Choi: Conceptualization, methodology, review, editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted by corresponding author Jeong-Ja Choi’s grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-K-2022-A0163-00076).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. Journal of Marketing Management. 1999, 15, 53–67.

- Yoon, Yang; Cho, Ga-Ran. The influence of purchase type, purchase context, and self-construal on consumer happiness. Korean Society for Consumer and Advertising Psychology. 2015, 16, 83–104.

- Henderson, L.W.; Knight, T. Integrating the hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives to more comprehensively understand wellbeing and pathways to wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing. 2012, 2, 196–221.

- Van Boven, L. Experientialism, materialism, and the pursuit of happiness. Review of General Psychology. 2005, 9, 132–142.

- Dong Woo-Ko; Seo Hyun-Sook. A structural framework on psychological adaptation and sequential changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Korean Psychological Association of Culture and Social Issues. 2021, 27, 351–389.

- Lee So-Jeong; Lee, Hoon. The effect of memorable tourism experiences reminiscence on subjective well-being: focus on the functions of autobiographical memory. Journal of Hospitality &Tourism Studies. 2022, 24, 50–68.

- Mackenzie, S.H.; Raymond, E. A conceptual model of adventure tour guide well-being. Annals of Tourism Research. 2020, 84, 102977. [CrossRef]

- Kwon Jang-Wook; Lee Hoon. A study on the travel experiences to prolong happiness. Journal of Tourism Studies. 2016, 28, 171–192.

- Kim Myung-Sun; Lee Gye-Hee. The effects of temple stay experience on hedonia, eudaimonia, and quality of life: Applying self-determination theory (SDT). Journal of Hospitality. 2023, 25, 39–58.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. Harper Perennial. New York, 1997, Vol. 39, 1-16.

- Kang Young-Ahn. Everyday life and happiness. Sogang Journal of Philosophy. 2016, 46, 41–68.

- Wiking, M.; Wiking, M. The little book of Hygge Danish secrets to happy living. Harper Collins. 2017, Vol. 240.

- Tswikai. When I blur: The prescription of the minds of 20 Great Psychologists. 2022.

- Ryu Yeon- Jae; Lee Seong-Joon. Influence of mindfulness on happiness: Focus on materialism and self-esteem. Korean Journal of Social and Personality Psychology. 2015, 20, 91–110.

- Lee Hye-Rim; Jeong Eui-Jun. The influence of players’ self-esteem, game-efficacy, and social capital on life satisfaction focused on hedonic and eudaimonic happiness. Journal of Korea Multimedia Society. 2015, 18, 1118–1130.

- Kler, B.K.; Tribe, J. Flourishing through SCUBA: Understanding the pursuit of dive experiences. Tourism in Marine Environments. 2012, 8(1-2), 19-32. [CrossRef]

- Son Seon-Mi. The relations between the programs, physical elements, visiting intention with experience orientation of Festivals. Event and Convention Research. 2007, 6, 1–23.

- Shieh, H.S.; Lai, W.H. The relationships among brand experience, brand resonance and brand loyalty in experiential marketing: Evidence from smart phone in Taiwan. Journal of Economics and Management. 2017, (28), 57-73.

- Santos, Vasco; Caldiera, Ana; Santos, Eulália; Oliveria, Simão; Ramos, Paulo. Wine tourism experience in the Tejo region: The influence of sensory impressions on post-visit behaviour intentions. International Journal of Marketing, Communication and New Media. 2019.

- Oh Sun-Young; Kang Hae-Sang. The effect of satisfaction and psychological well-being on festival experience. Northeast Asia Tourism Research. 2013, 9, 189–206.

- Yoon Seol-Min; Lee Tae-Hee. Effect relationship of the on emotion and satisfaction and emotion and satisfaction in theme park: Focusing on the perspective of experience marketing, Journal of Tourism and Leisure Research. 2012, 24, 289–308.

- Kim Myung-Sun; Lee Gye-Hee. The effects of temple stay experience on hedonia, eudaimonia, and quality of life: Applying self-determination theory (SDT). Journal of Hospitality. 2023, 25, 39–58.

- Yang Myung-Hwan. Physical activity and psychological well-being: Development of cognitive-affective states scale. Korean Society of Sport Psychology. 1998, 9, 113–123.

- Jung Young-Joo; Kwak Yi-Sub. The post experience emotion of marine sports on the psychological wellbeing, Terms of intermediation effects. Korea Coaching Development Center. 2018, 20, 21–31.

- Yoon Seol-Min. The effects of tourist experience from festival on satisfaction from perspectives of experience economy(4Es) and experiential marketing(SEMs): Focusing on the Seosan Haemieupseong Festival. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Studies. 2015, 17, 337–360.

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review. 1998, 76, 97–105.

- Oh Gang-Nam. Jangja. Seoul: Hyunamsa Temple. 1999.

- Kang Na-Hyun; Chan Lee. A study on non-everydayness characteristics in Jaime Hayon` s space. Journal of Korea Institute of Spatial Design. 2017, 12, 115–125.

- Song Kee-Hyun. The ethical consumption attitudes and the effects of tourists’ deviant behavior. Journal of Tourism Management Research. 2017, 21, 469–487.

- Oh, H., Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. Journal of Travel Research. 2007, 46, 119–132. [CrossRef]

- Park Jin-Sil. Escapefulness experience on festival satisfaction: A case of the Boryeong Mud Festival. (Master’s Dissertation), Seoul: Hanyang University. 2007.

- Lee Kyung-Yur; Lee, Hoon. Scale development of deviant festival behavior. Journal of Tourism and Leisure Research. 2020, 32, 99–119.

- Park Jun-Beum; Shim, Woo-Suk. A study on the influence of tourist attractions experience factors on experiential values and deviations. Journal of Tourism Management Research. 2021, 25, 209–227.

- Jung San-Seol. An analysis of changes in physiological and psychological well-being by travel stage. [Hanyang University]. Settlement theory. 2022.

- Kim Yong-Ho. Festival culture of Spain: Festivals in which the prototype is alive: European festival culture, focusing on fireworks festivals and saffron festivals. Yonsei University Press. 2003.

- Jung San-Seol; Lee, Hoon. A comparative analysis of psychological happiness and heart rate variability among travelers: Focusing on nature-based travel. Journal of Tourism Studies. 2023, 35, 99–133.

- Newman, A.; Ucbasaran, D.; Zhu, F.E.I.; Hirst, G. Psychological capital: A review and synthesis. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2014, 35(S1), S120-S138. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Kamgarpour, M., Georghiou, A., Goulart, P.; Lygeros, J. Robust optimal control with adjustable uncertainty sets. Automatica. 2017, 75, 249–259. [CrossRef]

- Stenseng, F. A dualistic approach to leisure activity engagement: On the dynamics of passion, escapism, and life satisfaction. 2009.

- Yan, Q., James, H.S., Xin, W.; Ben, H.Y. Examining the ritualized experiences of intangible cultural heritage tourism. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management. 2024, 31, 100843. [CrossRef]

- Oh Min-Jae; Lee Hyun-Jon. Effect of camping experience based on strategic experiential modules of experiential marketing on satisfaction and behavioral intention. Journal of Tourism and Leisure Research. 2019, 31, 387–406.

- Park Soo-Kyung; Ryu Mi-Ok; Jun Jae-Kyoon. The effects of Hanbok tourism experience on perceived value and satisfaction: A focus on Schmitt’s strategic experiential modules. Journal of Tourism and Leisure Research. 2019, 31, 39–57.

- Kim Myung-Sun. The effects of temple stay experience on hedonia, eudaimonia, and quality of life: Applying self-determination theory. [Seok Kim Mi-jin’s thesis, Kyung Hee University]. RISS Academic Research Information Service. 2021.

- Lengieza, M. L, Hunt, C.A.; Swim, J.K. Measuring eudaimonic travel experiences. Annals of Tourism Research. 2019, 74, 195–197. [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Witham, M. Dimensions of cruisers’ experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research. 2010, 49, 351–364.

- Oh Sang-Joon. The relationship between escapism, flow, perceived value and continuance intention - Focused on scuba divers. The Service Industries Journal. 2015, 13, 91–108.

- Lee Yeon-Hwa. Effect of experiential marketing on brand equity in local festival. Journal of Tourism Management Research. 2012, 16, 231–251.

- Yoon Seol-Min; Lee Choong- Ki. Analysis of the extended value-attitude-behavior hierarchy toward visitors to ancient palace by applying the individual and shared experiences of experience marketing. International Journal of Tourism Science. 2018, 33, 83–100.

- Garland, E.L., Farb, N.A., R. Goldin, P.; Fredrickson, B.L. Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: A process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry. 2015, (4), 293-314.

- Brülde, B. Happiness theories of the good life. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2007, 8, 15–49. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R. Black, W. Multivariate data analysis. London: Prentice Hall. 1998.

- Byung, Yul-Bae. AMOS 21. Modeling the old type equation. 2014.

- Yu, Jong-Pil. concept and understanding of structural equation models. Seoul: Han Narae Publishing. 2017.

- Byung Suh-Kang; Kim Gye-Soo. Spss17.0 Social science statistical analysis. 2002.

- Lee Hak-Sik; Lim Ji-Hoon. Concepts and understanding of structural equation models. Seoul: Han Narae Publishing, 2017.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research.1981, 18, 39-50.

- Bai, Lin-Zheng; Jin, Soo-Hahn. The impact of tourists’ experience on subjective happiness, psychological happiness and quality of life of healing tourism: Based on experience economy theory. Korean Journal of Hospitality and Tourism (KJHT). 2017, 26, 1–17.

- Choi, Un-Hoi; Lee, Mu-Yong. The patterns of deviation in urban music festival: Focusing on the ACC World Music Festival. Journal of Arts Management and Policy. 2019, 50, 65–100. [CrossRef]

- Jun Beum-Park; Shim Woo-Suk. A study on the influence of tourist attractions experience factors on experiential values and deviations. Journal of Tourism Management Research. 25, 209-227, 2021.

- Cho, Won-Deuk; An, Myoung-Sik. Effects of leisure experience on leisure flow and psychological happiness for leisure sports activity of elderly. Korean Journal of Leisure, Recreation & Park. 2015, 39, 25–36.

- Park Sung-Ho. A study on the Aristotle s eudaimonia. Journal of the Society of Philosophical Studies. 2017, 141, 63–84.

- Korea Tourism Organization. Korea Tourism Organization Innovation Promotion Plan. Daily Life Like Travel, Safety Like Daily Life. 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).