1. Introduction

Fallopian tubes are one of the least affected organs in gynecological cancers, accounting for less than 2% of all gynecological malignancies [

1,

2]. Tubal precancerous lesions play a crucial role in the development of ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC), making close clinical monitoring of these pathologies necessary [

3]. HGSC is one of the most aggressive ovarian cancers, with a 5-year survival rate of 49% [

4] andis responsible for the majority of deaths for ovarian malignant neoplasm, mainly because it is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage. It generally affects postmenopausal women, and has been widely associated with the BRCA 1-2 mutation, with an incidence of 16-44% in this population [

5]

.

A strong association has been found between HGSC and a tubal lesion considered to be a precursor, known as serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC)[

6].

Tubal cancer, serous ovarian and primary peritoneal carcinomas share overlapping ultrasonographic features, treatment strategies and prognoses, and therefore in most guidelines [

7,

8] these three entities are considered jointly. In addition, it can often be misdiagnosed and confused either with a benign pathology due to overlapping ultrasonographic features or with a primary ovarian tumor as a result of the fallopian tube being partially or completely involved in the tubo-ovarian mass. However, tubal cancer is considerably rarer than ovarian cancer and the aim of this review is to discuss the diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic aspects of tubal cancer to raise awareness of this disease which, although rare, deserves special attention.

2. Materials and Methods

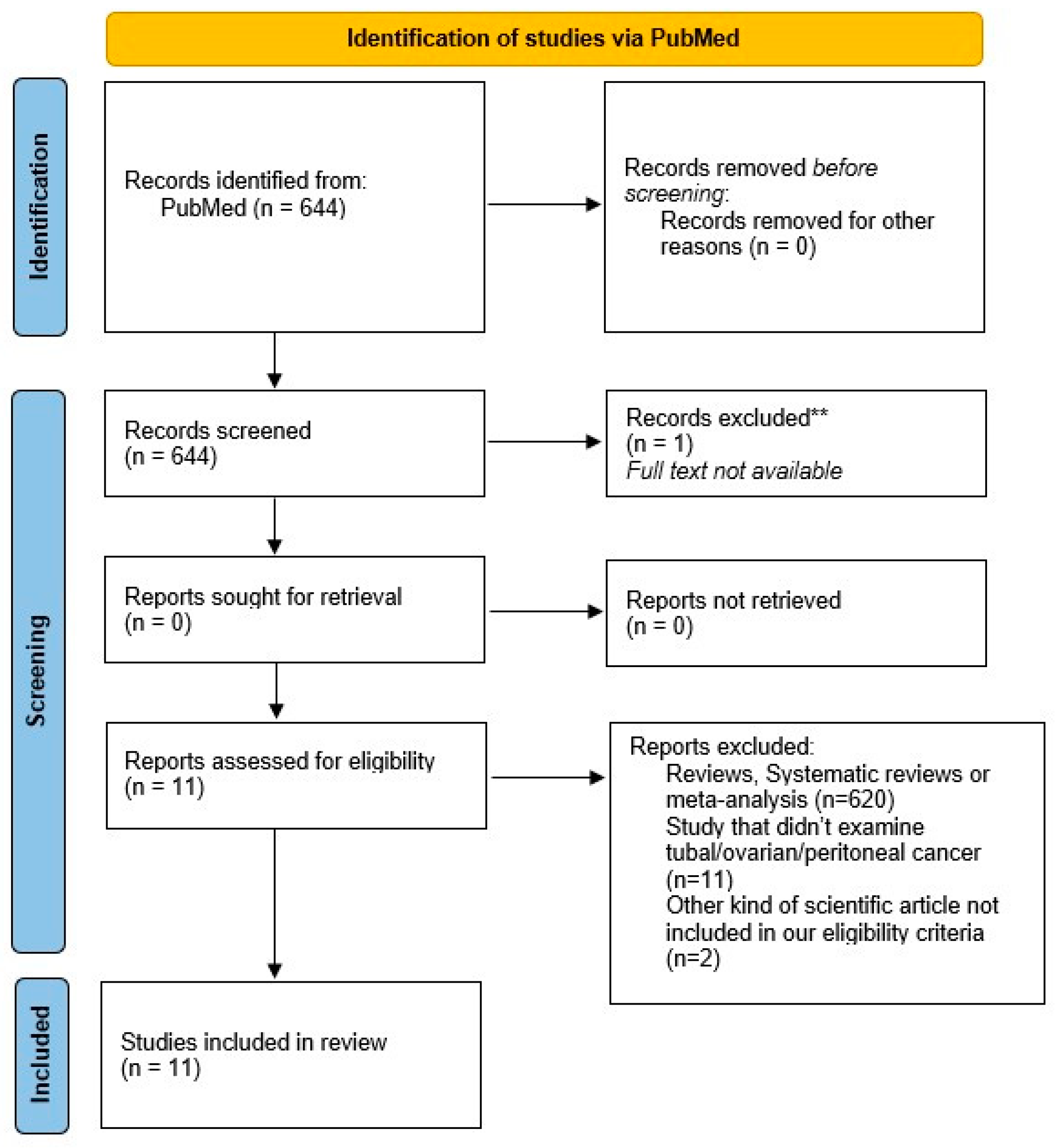

A search for relevant articles was conducted in PubMed from July 2014 to July 2024. The MeSH used for the search was: “tubal cancer AND surgery”.

We found 644 publications, 1 of which was excluded because the full text was not available. After excluding meta-analyses, reviews and systematic reviews, a total of 24 publications remained to be included in our review. All titles and abstracts were carefully assessed, and 13 trials were finally excluded because they did notfocus on the topic of the current review. The process followed the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The protocol has not been registered.

In order to provide an accurate description of the background to tubal precancerous lesions, possible progression to invasive cancer, imaging diagnosis, anatomopathological diagnosis, and staging a further electronic search was carried out using the MEDLINE online medical database (accessed via PubMed) to evaluate the existing literature on this topic. The following terms were used in our literature search: serous intraepithelial carcinoma or STIC, high-grade serous intraepithelial tubal neoplasia, isolated serous intraepithelial tubal carcinoma, prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy, tubal cancer and BRCA mutation. The titles and abstracts of the articles were carefully examined to select those relevant to our research question. We also conducted a thorough review of the bibliographies of the selected articles to identify additional papers for inclusion.

All selected articles were carefully assessed for relevance and scientific merit by two independent reviewers (I.C., F.P.).

A total of 31 articles were included for the purposes of our narrative review, i.e., a state of the art review of knowledge on fallopian tube cancer.

Figure 1 shows the literature search diagram.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram which included searches of Pubmed.

3. Tubal Cancer: From Precancerous Lesion to Invasive Carcinoma

The development of high grade serous ovarian cancer from the tubal epithelium has been widely described in the literature.

One of the most accepted theories on the pathogenesis of serous ovarian cancer suggests that it may originate from a precancerous tubal lesion known as serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma, referred to as STIC [

10], which may progress into invasive carcinoma of the fallopian tube or implant on the ovarian surface determining the development of ovarian carcinoma [

11].

During ovulation, the fluid ruptured from the follicles determines the release of free radicals, reactive oxygen species and other genotoxic substances that contribute to the carcinogenesis process through DNA damage and the consequent acquisition of somatic mutations and epigenetic alterations by the tubal epithelium and clonal expansion. This process appears to be accelerated in the presence of germline mutations and epigenetic inactivation of genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2.

In support of this hypothesis, tubal sterilization has been associated with a reduced risk of ovarian cancer, as well as bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, both in women with and without a BRCA mutation [

10]. On the other hand, some authors postulate that STIC can theoretically spread before salpingo-ophorectomy, explaining why peritoneal HGSC can develop even after salpingectomy [

12].

STIC is a rare finding, occurring in < 0.1% of the general population [

13] and approximately 2.3% of women at high risk of HGSC [

6].

Although rare, given its potential for evolutionary malignancy, in several centers, prophylactic salpingectomy is also performed during pelvic surgery for benign pathologies, even in low-risk patients, leaving the ovaries in situ, to preserve hormonal function, but reducing the risk of future development of ovarian cancer.

Even in low-risk women undergoing surgery for benign pathologies, the fimbriated end of the tube must be carefully examined by the anatomopathologist, as occult tubal cancer may be present. If STIC is detected in the fimbriated tube, the entire organ must be analyzed as invasive carcinoma may be present [

14]. For this reason, complete tubal specimen collection with detailed Sectioning and Extensively Examining the FIMbriated End (SEE-FIM) protocols are recommended [

7]. However, the clinical significance and management of those patients diagnosed with STIC but at low risk of developing ovarian neoplasia remains controversial.

In literature a progression of STIC in serous ovarian carcinoma is reported in 10% [

15] of women at high risk, although it is still not possible to conclude whether disease progression is absolutely related to the STIC or if it is a

de novo lesion. In addition, intraepithelial tubal metastasis may be indistinguishable from STIC [

7].

Tubal proliferation can sometimes be difficult to interpret as it may not be consistent with a diagnosis of STIC. Some tubal or mucosal proliferations may be atypical without showing features of intraepithelial carcinoma. These lesions, sometimes referred to as early serous proliferations (ESP), may be diagnosed as a serous intraepithelial lesion of the fallopian tube (STIL) or a tubal intraepithelial lesion in transition (TILT), but even in these cases the management has not been defined.

A possible evaluation for BRCA mutation has been suggested to identify women at higher risk, but data are still insufficient [

14].

In a recent review, Patrono et al. [

16] found that isolated STIC in patients with BRCA mutations developed into primary peritoneal cancer in 4.5% of cases underlining the need for appropriate follow-up to detect recurrence at an early stage.

Nevertheless, there is insufficient data to determine the most appropriate follow-up for women with an incidental diagnosis of STIC, and the use of CA125 sampling or pelvic ultrasound remains controversial [

16].

In a recent review Steenbeek et al. [

17] highlighted that in patients with mutated BRCA, the risk of subsequent HGSC at 5 years is 10.5% and at 10 years is 27.5%, which is significantly higher than the risk of HGSC after adnexectomy in patients without STIC findings, reported in this case to be 0.3% at 5 years and 0.9% at 10 years.

Although the potential for malignant progression of STIC is known, there is still a lack of data on the management of these women. A German survey [

18] found that as the progression of STIC to invasive cancer is estimated to be around 7 years, follow-up is generally prolonged and usually consists of annual TVS and associated serum CA125. In the case of isolated STIC, some centers propose BRCA mutation testing and laparoscopic staging surgery, although data are lacking. In addition, some centers suggest ipsilateral oophorectomy in premenopausal women and bilateral oophorectomy in menopausal women while adjuvant chemotherapy is not generally recommended.

2024 NCCN guidelines [

8] suggest follow-up with or without CA-125 testing in the absence of invasive cancer, and surgical staging with surveillance or chemotherapy if invasive cancer is present in specimens.

As with other guidelines, NCCN also agree that genetic counselling and testing should be performed if not previously done in the event of STIC, but they also agree that the beneficial role of surgical staging and/or adjuvant chemotherapy in the incidental finding of STIC is still being debated.

An accurate study of the STIC entity is essential in future prospectives, whether to perform only salpingectomy in premenopausal women at high risk of HGSC and deepening ovariectomy after menopause [

5]

.

4. Imaging Diagnosis

The diagnosis of both primary peritoneal cancer and fallopian tube cancer is generally postoperative [

8], although the literature describes pathological aspects on imaging modalities of the fallopian tubes.

Affected fallopian tubes appear macroscopically as enlarged structures with irregular inner walls due to the presence of solid tissue protruding into the lumen. Hemorrhage or necrosis are very common. [

2]. Ludovisi et al. [

2] described the main ultrasonographic features of tubal carcinoma. In most cases, the affected tube shows a cystic, sausage-like appearance. In contrast to acute inflammation, it presents thin walls with an irregular inner surface due to the presence of solid tissue and papillary projections. On power Doppler, the walls and solid tissue are strongly vascularized. Tubal carcinoma may present alternatively, as a tubal structure with a voluminous solid component or as a completely solid mass with no fluid content. If present, the inner cystic fluid is usually anechoic, and the affected tube may be erroneously misdiagnosed as a hydrosalpinx.

In flogistic pathology the appearance of the fallopian tubes is quite different and may be confusing to the untrained observer. Acutely infected tubes often have a “cogwheel” appearance in transverse section due to the edematous inner wall protruding into the lumen, whereas in longitudinal section the same walls determine the presence of incomplete septa. These septa are usually highly vascularized. In chronic salpingitis the internal protrusions are thinner and delineate a characteristic sign called “beard on a string”, the tube appears elongated, the walls are thinner and less vascularized. These sonographic aspects overlap with those of tubal cancer and make the differential diagnosis difficult. If the tubal mass is carefully examined, the internal protrusion within the lumen is composed of a solid component, the fluid content in acute flogosis is usually ground glass due to the presence of pus in the tube, and the tubal walls are thicker. For this reason, the lesion must be examined both longitudinally and transversely, and in the latter case the presence of incomplete septa or the cogwheel appearance tilts the balance towards a benign diagnosis.

Tongsong et al. [

19] confirmed these ultrasound patterns, stating that in their series the affected tubes also showed a sausage-shaped structure on TVS with solid tissue protruding into it. In contrast to benign tubal pathologies, incomplete septa were present in only 33.3% of cases. In 40% of patients, the ovaries appeared normal.

In their series, they also reported a few cases that were misdiagnosed as tubal carcinoma preoperatively but were found to be ovarian carcinoma after surgery. According to Tongsong et al., the misdiagnosis was due to the presence of an ovarian cystic structure with overlapping characteristics with tubal pathology, mimicking a sausage-shaped aspect. In 62% of cases, tubal cancer is an incidental finding in asymptomatic women and is often discovered at an advanced stage [

2]. Tubal cancer can be predicted on TVS by applying IOTA simple rules with pattern recognition with a sensitivity of 86.7% and a specificity of 97.4% [

19].

In the presence of an adnexal cyst, it is essential to search carefully for the ipsilateral ovary. In the case of a malignant lesion, it isimportant to distinguish between ovarian or tubal origin, but in difficult cases this is not primary, as these pathologies share the same classification for staging, treatment and prognosis [

2].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a second line imaging technique often used in preoperative staging of gynecological diseases. Tubal carcinomas appear on MR as a hyperintense T2-weighted signal and a hypointense T1-weighted signal showing a solid aspect [

20].

The actual staging system for ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal cancer according to the FIGO [

21] classification should be based on the surgical findings of primary debulking surgery (PDS). Nevertheless, some authors argue that imaging modalities, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance, can also be used to recognize the origin of the lesions and tumor stage when combined with cytological examination and tumor marker levels without resorting to diagnostic surgery in advanced stages [

22].

5. Anatomopathological Diagnosis

The diagnosis of tubal pathology can be challenging, particularly in the case of incidental pre-cancerous lesions. To provide a standardized, reproducible diagnosis, the Sectioning and Extensively Examining the FIMbri-ated End, SEE-FIM, protocol has been developed. The SEE-FIM procedure consists of embedding the entire fallopian tube with an explicit focus on the fimbriated end [

13]. Nevertheless, the SEE-FIM protocol cannot be applied by default, given the low probability of finding a STIC lesion in the general population, and the fact that STIC has no clinical consequence when diagnosed concomitantly with HGSC. Therefore, this protocol should be used in selected cases, in women at high risk, or in the presence of atypical findings on initial anatomopathological evaluation [

13].

In order to standardize the diagnosis of STIC, Bogaerts et al. [

13], based on a consensus statement, developed a few recommendations to describe the diagnostic workup that should be performed by a pathologist. The proposed process is divided into five domains, including processing and macroscopy, microscopy, immunohistochemistry, interpretation and reporting, and miscellaneous. Consensus was reached through a Delphi study involving 34 expert pathologists from 11 countries worldwide.

The examination starts from a slide at low magnification, maximum 5 times magnification, looking for areas of cytological atypia which, if present, are mandatory to examine at higher magnification with the aim of recognizing the distinctive morphological features proposed by the consensus for the diagnosis of STIC.

Characteristic cytological changes are nuclear pleomorphism, nuclear enlargement, high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio and nuclear hyperchromasia.

A second step is the evaluation of immunohistochemistry, which is performed in all cases of atypical morphology, especially p53 and Ki67. An abnormal p53 must always be found to establish the diagnosis of STIC, while for Ki67 the data are confused, a proliferation index higher than 10% is considered abnormal, even if the cut-off values are still unclear.

Diagnosis is more difficult in lesions that do not meet the diagnostic criteria for STIC, for example in so-called p53 signatures, characterized by an aberrant p53 staining pattern in at least 12 adjacent cells but no clear cytomorphological atypia on haematossilin and eosin staining, or in STIL and TILT, which resemble STIC but where immunohistochemical staining for p53 and Ki-67 does not fully support the diagnosis. Secretory or stem cell outgrowths (SCOUTs) are a group of proliferative lesions in the fallopian tube epithelium that are not associated with p53 mutation but show overlapping cytological changes that make the diagnosis difficult [

13].

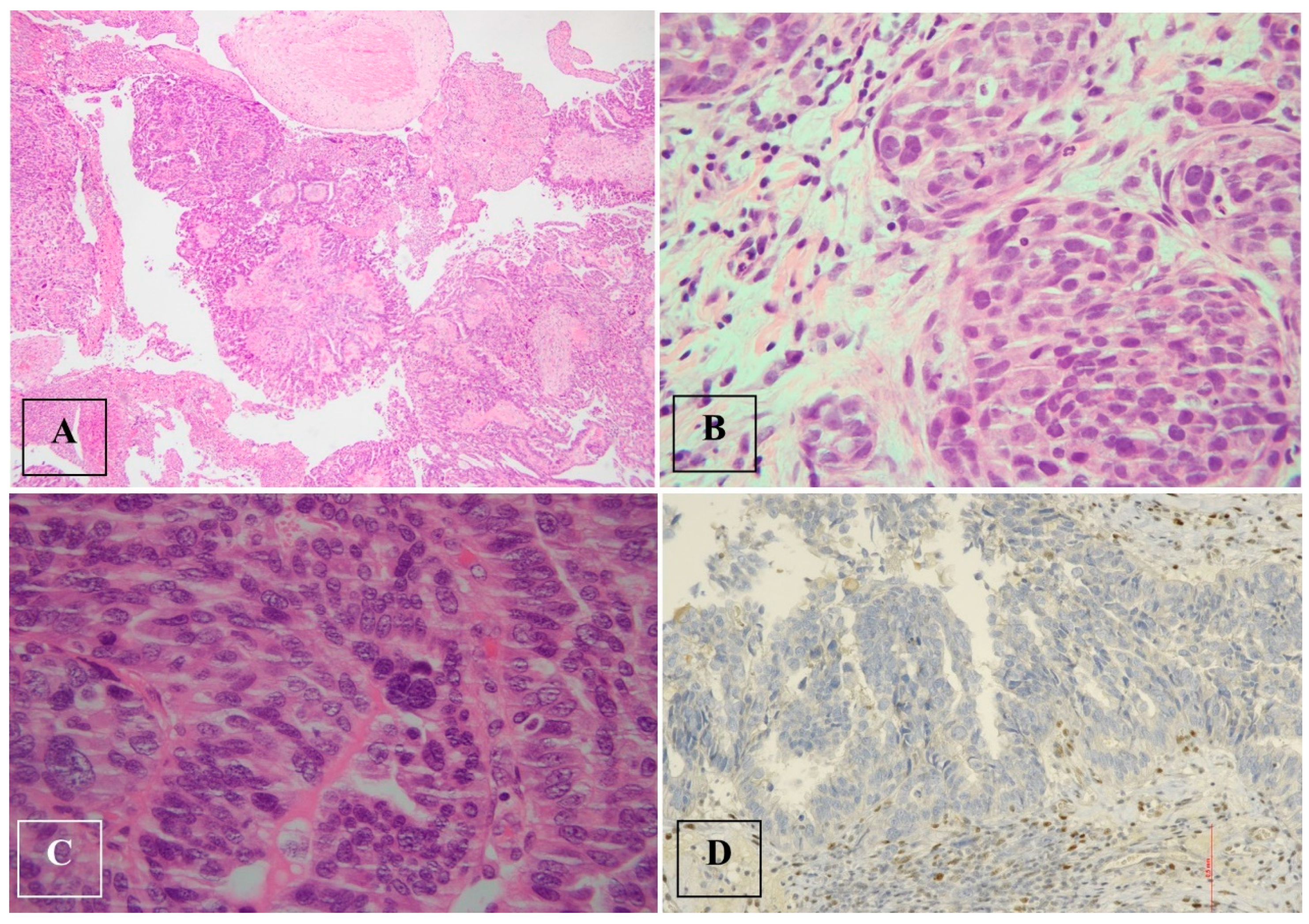

HGSC is an inhomogeneous disease with different histological features, coexisting with STIC, occurring at different ages, and showing different clinical outcomes [

23].

The histological features of HGSC classically show a papillary, micropapillary or infiltrative pattern in more than 50% of the tumors, often with a desmoplastic stroma [

23].

6. Staging and Management

Fallopian tube, primary peritoneal and ovarian cancer are considered together in almost all major guidelines because of their common diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, especially in the case of HGSC, where the pathogenesis is also shared.

The 2019 ESGO-ESMO Consensus Conference Recommendations on Ovarian Cancer [

7] state that most cases of HGSC of the fallopian tube arise from STIC and therefore SEE-FIM is recommended with a level of evidence III and strength of recommendation A, even in low-risk cases.

Standardized diagnosis of STIC is essential. One of the main reasons is that it has prognostic implications related to an increased risk of peritoneal carcinomatosis, which opens the debate about the usefulness of surgical staging or chemotherapy in women with isolated and incidental STIC. In any case, there is consensus among clinicians that the findings of STIC require follow-up strategies for the prevention of tubo-ovarian or peritoneal cancer [

13].

According to NCCN guidelines [

8], follow-up options include observation alone with or without CA-125 testing if there is no evidence of invasive cancer, but it is still not clear whether surgical staging and/or adjuvant chemotherapy would be beneficial. There is consensus that genetic evaluation is mandatory in women with incidental findings of STIC.

On the other hand, in the case of invasive cancer, surgical staging with observation or chemotherapy is usually required.

For surgical staging, minimally invasive surgery is generally the first choice to assess the extent of the disease, to allow the eventual diagnosis through frozen section or to decide in cases with peritoneal carcinomatosis the need to perform a PDS or an interval debulking surgery (IDS) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) [

24]. The upper abdomen, bowel surfaces, omentum, appendix and pelvic organs should be carefully examined and abnormal findings should be biopsied and cytology obtained by peritoneal washings. If cytoreduction is possible, a total bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is required as well as removal of 2 cm of the infundibolo-pelvic ligament and the peritoneum surrounding the ovaries and fallopian tubes. To avoid traumatic exfoliation of the cells, an endobag should always be used to retrieve the specimens.

Hysterectomy should be considered in women with an increased risk of endometrial cancer, BRCA1 mutations, Lynch syndrome or exposure to Tamoxifen.

Recognizing the primary origin of HGSC is fundamental. It should only be classified as ovarian in origin if both tubes appear normal on macroscopic examination and SEE-FIM protocol. Staging is IIA tubal HGSC if STIC and ovarian HGSC are present simultaneously.

Synchronous independent neoplasms are very rare; in the presence of lesions in both the ovary or fallopian tubes and the endometrium, they should be considered as metastases from one of these sites.

The 2024 NCCN guidelines [

8] recommend the following elements to be evaluated for staging: location and size of lesions, presence or absence of surface involvement, integrity of specimen; histological type and grading; presence of implants supposed to biopsy; cytology of fluid collected; evaluation of lymph nodes examined and evidence of STIC, endometriosis and endosalpingiosis.

The treatment of primary peritoneal and fallopian tube cancer is the same as the treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer and it usually consists of surgical staging and debulking surgery, which may be followed by systemic chemotherapy. However, in advanced stages, when primary debulking surgery is not possible due to advanced age, frailty, poor performance status, co-morbidities, or inability to perform cytoreduction,

neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) with interval debulking surgery (IDS) should be considered. In early-stage disease, instead, surgery alone and close follow-up may be enough [

8].

Debulking surgery for suspected malignant ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal neoplasm should be performed by open laparotomy with a vertical midline abdominal incision; minimally invasive techniques may be an option only in early-stage disease or when the surgeon judges that optimal debulking, i.e., residual disease less than 1 cm, can be achieved in selected patients after NACT.

Fertility spearing may be considered in selected patients who wish to achieve pregnancy and who appear to have unilateral stage IA tumors, or in those with bilateral stage IB tumors where the uterus is preserved.

7. Exceptional Scenarios

Although tubal carcinoma is a rare disease, it may be encountered in clinical practice and it is therefore important to be able to recognize it and to be up to date with the management of these patients. To this purpose, we report two clinical cases from our clinical practice: a case of incidental STIC with the occurrence of peritoneal carcinoma years later and a case of primary tubal cancer.

7.1. Case 1

We present the case of a 60-year-old woman who underwent prophylactic adnexectomy for BRCA 2 mutation. The patient was tested, after genetic counseling, because of a family history of breast cancer in her mother, maternal aunt and paternal cousin. Prior to surgery, the patient had undergone a six-monthly surveillance protocol with pelvic ultrasound and CA125 combined with Eco mammary and breast examinations every six months and annual mammography and breast magnetic resonance.

She was in good clinical condition, nonsmoking, with a body mass index (BMI) of 26.7 and had been in physiological menopause since the age of 47. The patient’s personal medical history revealed hypertension on medication, no previous abdominal surgery.

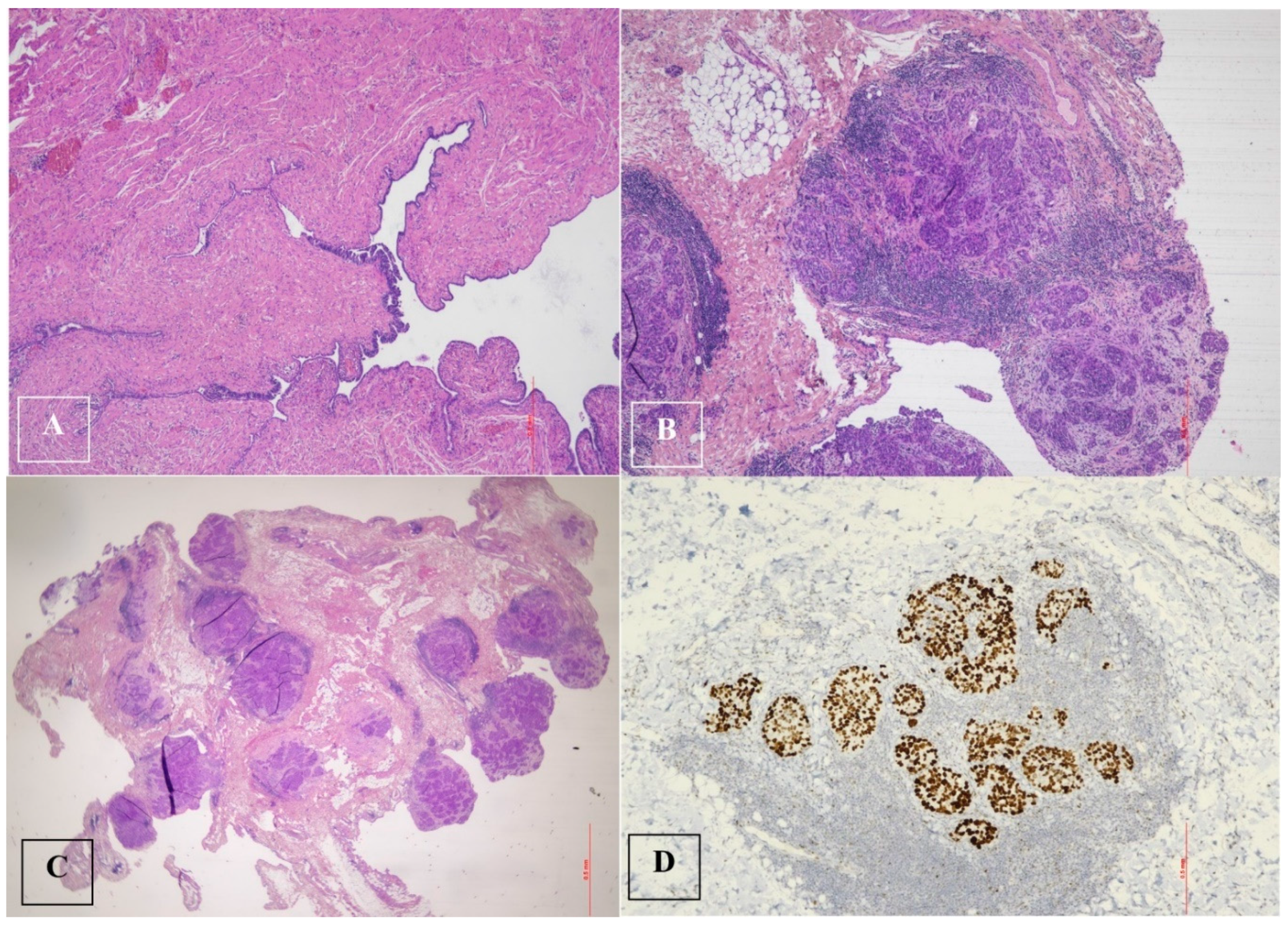

Histological examination after adnexectomy of the distal part of the right salpinx showed the presence of focal papillary proliferation with multilayered epithelium with marked cytological and immunophenotypic atypia characterized by p53+Wt-/+. The proliferative index, assessed with KI 67, was equal to 60% of cellularity, showing no signs of clear invasiveness, however the presence of discoid cells in the tubal lumen was consistent with the diagnosis of STIC serous intraepithelial tubal carcinoma (

Figure 2).

No documentable neoplastic proliferation in the left adnex was detected. The first post-operative transvaginal ultrasound scan showed a regular pelvis with normal uterus and endometrium, adnexal fields without any detectable tumefactions.

The case was discussed by the multidisciplinary oncology board and the patient was referred for follow-up and underwent six-monthly mammography and gynecological check-ups with ovarian tumor markers. Due to a senological indication for prophylactic purposes, the patient underwent a bilateral mastectomy one year after the pelvic surgery. All follow up tests were negative for the next 4 years.

Four years later, the serum CA125 level was slightly elevated at 46 U/ml. The simultaneous transvaginal ultrasound examination showed a normal pelvis following bilateral adnexectomy, but with a minimal fluid collection in the adnexal field of 15 mm on the right side and 20 mm on the left side.

Less than one month later, CA125 was elevated to 72 U/ml and a CT scan was requested. The CT showed a pelvic layer of endoperitoneal fluid between the intestinal loops and in the right inferior parietocolic area.

In the hypogastric region, several mesenteric lymph nodes were noted, the largest of which had a maximum diameter of approximately 9 mm and in the mesogastric region, an anterior paracaval lymph node measuring approximately 11 mm was detected.

No lymph node swelling was seen in the retroperitoneal spacepara-aortic region or along the iliac vessels.

Colonoscopy was negative.

Positron emission tomography (PET) with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) showed suspicion of lymph node heteroplasticity and peritoneal involvement.

Diagnostic laparoscopy was therefore indicated and revealed the presence of an abundant ascitic effusion sent for cytological examination.

A picture of miliariform disease was described, mainly involving the right hemidiaphragm, the omentum, the parietocolic duct, the colon and cecum, both pelvic infundibula, the vaginal rectus septum and the peritoneum of the uterine bladder. Large excisions of the peritoneum were made for histological evaluation.

Final histological examination revealed metastasis of high grade serous carcinoma.

3 cycles of chemotherapy were administered according to the Carboplatin and Paclitaxel scheme. CA125 levels decreased from 1337 u/ml before the first cycle to 295 before the third cycle.

The CT of the chest and abdomen performed after the third cycle of chemotherapy showed a peritoneal carcinomatosis that had progressed compared to the previous control. The patient underwent a tentative interval debulking surgery. The preliminary laparoscopic view showed the diaphragm bilaterally affected by plaque carcinomatosis, sparse carcinomatous nodules at the level of the greater curvature of the stomach, small omentum, several intestinal loops and mesentery affected by carcinomatosis. Omental cake and peritoneal carcinomatosis were described.

The pelvis appeared frozen and inaccessible with the uterus firmly attached to the wall of the sigmoid colon. Because of the impossibility of cytoreduction based on the laparoscopic predictive model for optimal cytoreduction known as “Fagotti score” [

25], extensive biopsies were performed.

A histological examination revealed multiple neoplastic nodules of carcinomatosis infiltrating the tissue with a minimal fibroinflammatory reaction and areas of necrosis.

7.2. Case 2

We present the case of a 72-year-old woman with an incidental finding at TVS of an adnexal cyst. Family history was positive for endometrial cancer and gastrointestinal tumors while patient anamnesis was positive only for hypertension. She had a history of abdominal surgery for appendicitis, cesarean section, and laparotomy for diverticulitis more than 30 years ago.

A pelvic mass was found during a routine gynecological examination.

The tumor marker CA 125 was negative. The patient was asymptomatic and did not report any vaginal discharge, pelvic mass or abdominal pain.

A contrast MRI confirmed the presence of right tubal dilatation with solid tissue of 27x18 mm.

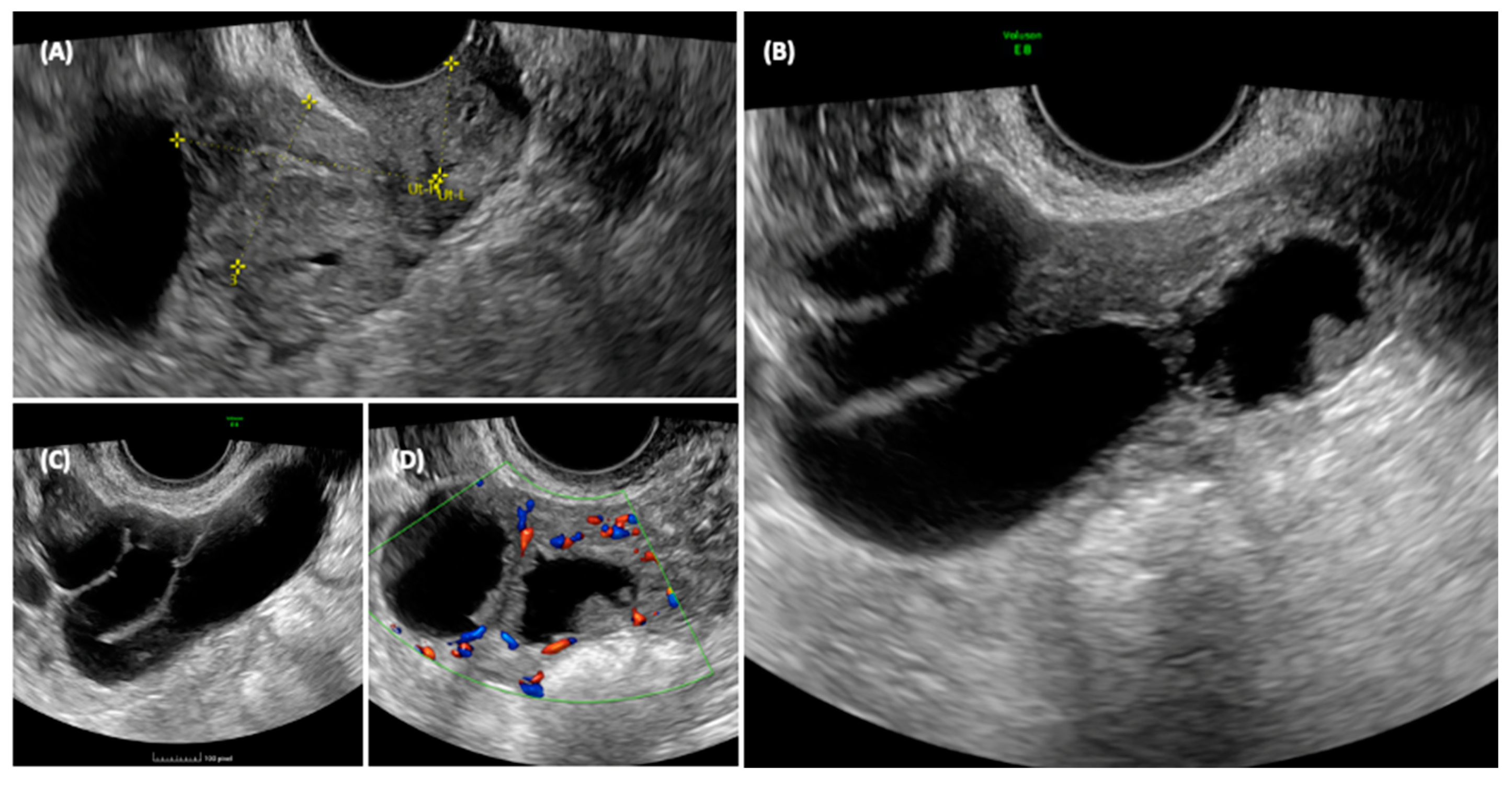

She was sent for an outpatient II level ultrasound. On transvaginal ultrasound, a 70 x 45 mm multilocular elongated cystic formation was described in the right adnexal field, posterior to the uterus, with anechoic content, characterized by irregular internal walls due to the presence of multiple papillae, the largest measuring 15 x 8 mm, vascularized on color Doppler with color score 3. Approximately 3 cm of solid tissue was visualized cranially to this structure, with inhomogeneous content and poorly vascularized on color Doppler (

Figure 3). The ipsilateral ovary was not visualized while the uterus and contralateral ovary appeared normal. Endometrial polyps were suspected due to the presence of a hyperechogenic structure within the endometrium.

Ultrasonographic aspect of the pelvis is shown in

Figure 3.

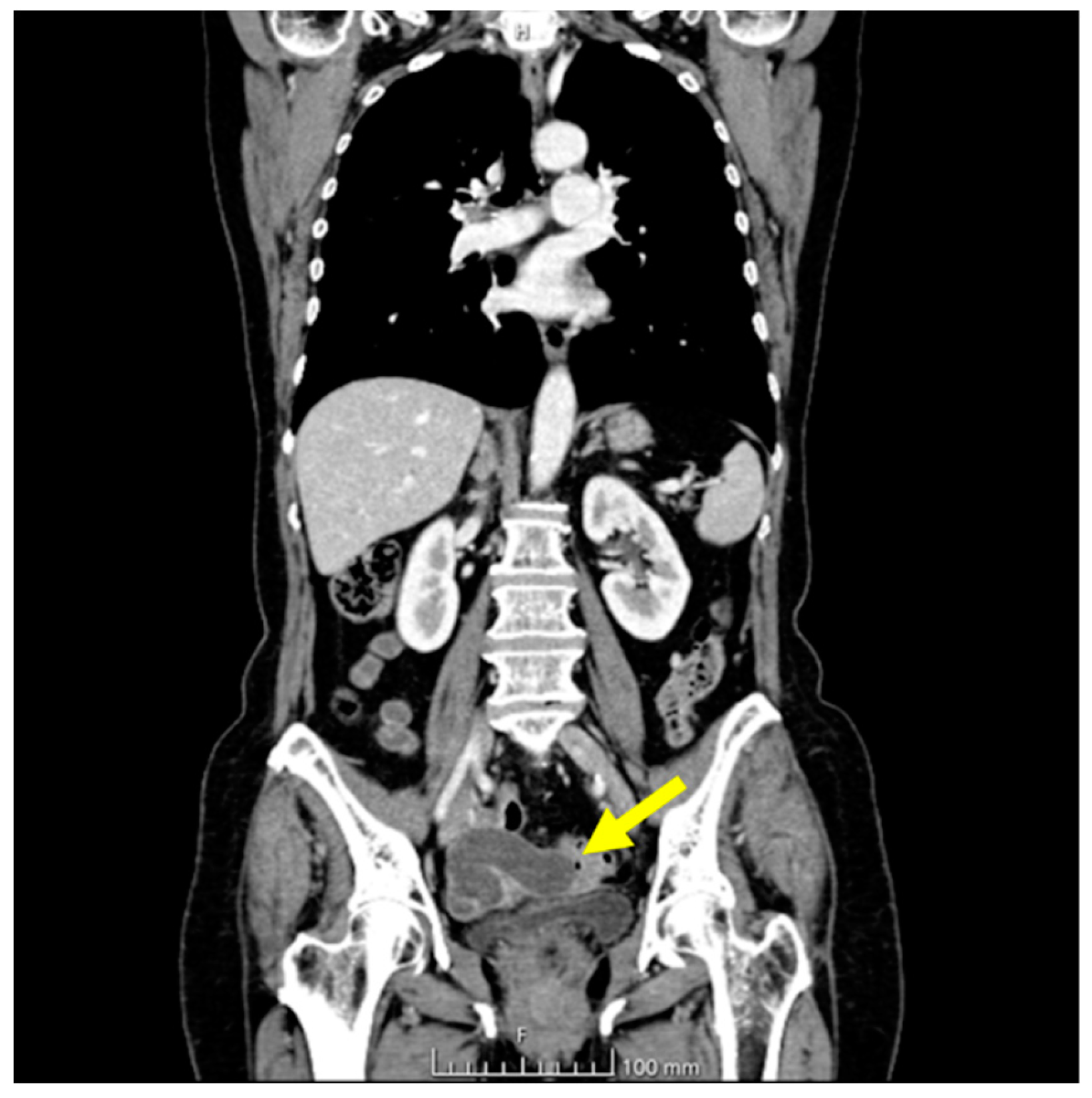

The ultrasonographic appearance was considered suspicious for tubal neoplasia and the patient was referred for surgery. Prior to surgery, the patient underwent a CT scan with contrast, which showed the uterus and adnexa with poorly visible cleavage planes, with the presence of a tubular cystic mass compatible with hydrosalpinx. The uterus and adnexa also appeared difficult to separate from the small bowel and sigmoid colon. No ascites or metastatic lesions were present (

Figure 4).

An exploratory laparoscopy was performed, showing an upper abdomen with regular diaphragmatic surface peritoneum, normal liver, stomach and omentum morphology. Observation of the lower abdomen revealed a serpiginous swelling due to an actasic process of the right fallopian tube,about 10 cm in length, adhering tenaciously to the rectus sigmoid and the posterior wall of the uterus, leading to an obstruction of the Douglas. Cerebroid, whitish, friable and frankly neoplastic material was observed oozing from the fimbriated portion. A Fagotti score of 2 was obtained and the conversion from laparotomy to cytoreductive surgery was decided. The patient underwent bilateral adnexectomy, radical class B1 hysterectomy according to Querleu-Morrow, pelvic peritonectomy of the Douglas and parietocolic ducts, omentectomy, aspiration of peritoneal fluid. An extemporaneous histological examination of the neoformation was requested, which was positive for a carcunomatous epithelial proliferation of tubal origin.

The final histological examination revealed a high-grade serous carcinoma of the right tuba involving the ipsilateral ovarian surface, parenchyma and adnexal tissues (

Figure 5).

Complete absence of expression in tumor cell nuclei, corresponding to p53 nonsense mutation (non-neoplastic stroma serves as internal positive control).

Neoplastic angiolymphatic permeation was documented. Uterus, omentum and peritoneum were free of carcinomatous infiltration.

The case was discussed at the gynecological oncological multidisciplinary group, a genetic counselling was provided, and BRCA1 mutation testing was requested. The patient was considered then eligible for adjuvant chemotherapy.

8. Discussion

Fallopian tubes are 11-12 cm long seromuscular structures originating from the uterine horns and extending laterally, connected to the ovary by the mesosalpinx. In the physiological state, the lumen is 1 mm, while the tubular structure is constituted by three strata which are from the outside to the inside: the serosal, the muscular layer divided into an inner circular and an outer longitudinal stratum, and the inner mucosa covered by cilia [

26]. They are classically divided into 4 parts: the intramural portion, the isthmus, the ampulla and the infundibulum [

26] and receive vascular apport from anastomoses between the ovarian artery and the ascending branches of the uterine artery.

Inflammatory cytokines resulting from exposure to ovulation and retrograde menstruation may support carcinogenic mutations in the fimbriated portion of the fallopian tube determining the occurrence of preneoplastic lesions [

27].

As reported above, a strong association has been found between HGSC and serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. This association suggests a possible progression from STIC to ovarian and peritoneal HGSC, although the STIC itself is likely to have metastatic potential [

6].

A milestone in the understanding of epithelial ovarian carcinogenesis is the work of Kurman [

3]. Historically, his group proposed a dualistic model of epithelial ovarian carcinogenesis, dividing lesions into type I and type II tumors. Type I tumors include endometrioid, low-grade serous, clear cell and mucinous carcinoma, while type II comprises high-grade serous carcinoma, carcinosarcoma and undifferentiated carcinoma. Type I neoplasms generally show an indolent nature and are responsible for 10% of deaths due to ovarian cancer, while type II are generally detected in an advanced stage and are highly aggressive with a massive interest of mesentery and omentum at diagnosis. Type II tumors account for 90% of deaths from ovarian cancer, moreover, type II neoplasms show chromosomal instability, which is generally not present in type I cancers and are characterized by TP53 mutations.

This pattern supports the close relationship between tubal preneoplastic lesions and ovarian cancer, hence the presence of a p53 mutation has been recognized in both entities [

5]. Type I carcinomas generally develop from benign or borderline precursors, whereas in type II the development of malignant lesions is generally

de novo, with the only precursor found being STIC [

3].

Even though STIC is a precancerous lesion confined within the epithelium, it presents cells that are able to spread even without invading the surrounding tissue [

3]. The most widely accepted theory is that dissemination is achieved by the detachment of cells from the surface of the fallopian tube [

28]. The necessary time for this event progression is not yet known, determining a problem in programming screening; moreover the majority of high risk women for developing ovarian cancer who received an effective sonographic diagnosis of tubal/ovarian neoplasm, had had a previous regular examination 6-12 months before [

3].

Because of their proximity to the fimbriated ends of the fallopian tubes, the ovaries are usually the first organ to be affected by the desquamative process of STIC cells and the consequent possible development of ovarian HGSC, although the cells may also directly adhere to the peritoneal surface or omentum to form peritoneal primary HGSC [

12].

Visvanathan et al. [

28] conducted a multi-centre study to comprehensively examine risk and protective factors associated with tubal precancerous lesions in women at high risk of ovarian cancer. They found a prevalence of unique tubal lesions in 6.3% of the cases, with no significant differences in BRCA 1 or 2 mutations. Invasive cancer was found in older women, making age the only significant predictor of having a malignant lesion.

Tubal cancer may display several histotypes the most frequent is adenocarcinoma, mainly serous papillary carcinoma (80%), followed by clear cell carcinoma (2%), endometrioid carcinoma (7%) and squamous cell carcinoma, although in most cases this cannot be clearly distinguished from ovarian cancer [

2].

In the majority of cases, 87-97%, lesions are unilateral, with an estimated mean tumor size of 5 cm [

2]. Patients usually have a history of vaginal discharge, abnormal uterine bleeding and lower abdominal pain with a palpable pelvic mass or ascites [

2]. Latzko’s triad of symptoms is rare (10%) but highly diagnostic of tubal cancer and is defined by the presence of intermittent colicky pelvic pain, a pelvic mass and bloody aqueous vaginal discharge known as ‘hydropstubae profluence’.

Sherman et al. [

29] reported a rate of clinically occult cancer in 2.6% of high-risk patients undergoing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. BRCA 1-2 mutations, postmenopausal status, elevated CA125 levels and abnormal findings on transvaginal ultrasound were identified as risk factors in these patients.

An open question is the relationship between the benefits of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomies (RRSO) and the potential complications of early surgical menopause. It remains unclear at what age surgery provides the most appropriate protection with minimal adverse effects due to hormone withdrawal. Recent data suggests that salpingo-oophorectomy should be performed between the ages of 30 and 35 years in patients with the BRCA 1 mutation, while it can be delayed to around 40-45 years in patients with the BRCA 2 mutation. Hence the idea of performing an early salpingectomy and delaying oophorectomy to a later age to reduce hormonal complications, although this approach is still under investigation.

Follow-up protocols are the only available strategy to detect early disease in high-risk patients. Despite this, Sherman et al. [

29] found normal CA125 levels and TVS in all patients diagnosed with STIC.

In the case of metastases from serous endometrial tumors, lesions resembling STIC may be observed, which poses a problem for a differential diagnosis. Some authors suggest that in these cases a careful microscopic examination of the endometrium should be performed in patients undergoing RRSO [

29].

An aspect that needs to be taken into account is that women with a known BRCA mutation may experience high levels of psychological distress due to the possible occurrence of cancer and may need psychological support, even though most cancer concerns seem to recede after RRSO [

30].

The current literature review, including the works selected through the search string on PubMed, showed that tubal carcinoma is often classified under the term “ovarian cancer” both in clinical trials and in guidelines. From a clinical perspective, in terms of surgical therapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy in cases of advanced disease, adjuvant chemotherapy in cases of early disease, and follow-up, the entities are indeed similar. However, it is necessary to consider the distinction between the two entities in the diagnostic phase and during the preoperative radiological staging. The primary tubal carcinoma, in fact, shares the characteristic with ovarian carcinoma of being definitively diagnosed only after a surgical procedure that involves the removal of the lesion and subsequent histological examination. During the diagnostic suspicion phase, tubal carcinoma is differentially diagnosed with various pelvic diseases, both tubal and extra-tubal (such as intestinal, peritoneal, retroperitoneal diseases), both benign and malignant. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the clinical entity of tubal carcinoma itself to avoid a diagnostic delay and consequently a therapeutic delay that could negatively impact the patient’s prognosis.

The 11 studies selected from the search string reveal that recent clinical trials have focused on the role of RRSO in women carrying BRCA gene mutations [

29], on the possibility of diagnostic radiological/biochemical screening to prevent or early diagnose tubal/ovarian cancer [

27,

31,

32], on the role of CT in the preoperative staging of advanced ovarian-tubal diseases [

22], on the identification of risk and protective factors for tubal/ovarian neoplasms to target high-risk populations to control through closer preventive clinical surveillance [

27,

31,

33], and on the comparison between PDS and IDS in the surgical therapy of advanced stage diseases [

34,

35,

36]. The datasets from which these data arise are often the same [

22,

34,

35] or come from the same research project that has published preliminary and definitive data [

31,

33,

37].

As highlighted in the specific columns of

Table 1, the percentage of tubal/ovarian patients undergoing PDS and IDS varies widely depending on the patient populations, the protocol implemented in each Center, and the expertise of the surgeon managing tubal/ovarian disease. To homogenize this trend, it would be crucial to standardize intraoperative surgical staging and utilize validated, reproducible, and well-acquired tools, such as the so-called Fagotti score (laparoscopic predictive model for optimal cytoreduction in advanced ovarian carcinoma) [

24,

25] and the Vizzielli score (laparoscopic risk-adjusted model to predict major complications after primary debulking surgery in ovarian cancer) [

38].

9. Conclusions

The cornerstone of tubal/ovarian tumor treatment is optimal cytoreduction with the surgical removal of all the disease to ensure the absence of any macroscopic residual tumor and possibly adjuvant chemotherapy according to the FIGO staging [

8]. Obtaining a correct radiological differential diagnosis in the initial diagnostic suspicion phase in order to promptly refer the patient with tubal/ovarian cancer to the appropriate referral Center is essential to ensure the best possible prognosis for that woman. Having a dedicated surgical team and an expert pathology anatomy service for the differential diagnosis of neoplastic and preneoplastic lesions of the tubes is mandatory.

This review demonstrates that the multidisciplinary team managing the oncological gynecological patients must have a complete understanding of the pathophysiology, biology, and natural history of tubal neoplasm for adequate treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and F.P. .; methodology,I.C., A.M., A.C., AF.C., F.P.; investigation, I.C., S.P., M.G., EV. D., A.C.; resources, I.C., A.M., F.P. data curation, I.C., L.L., E.Z., F.P.; writing—original draft preparation, I.C. and F.P.; writing—review and editing, A.M., E.Z., AF.C., F.P.; visualization, S.P., M.G., L.L., M.D.; supervision, AF.C., A.M., A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be asked to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Prof. Georgina Porro for the support in English language revision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gottschau, M.; Mellemkjaer, L.; Hannibal, C.G.; Kjaer, S.K. Ovarian and tubal cancer in Denmark: an update on incidence and survival. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016, 95, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludovisi, M.; De Blasis, I.; Virgilio, B.; Fischerova, D.; Franchi, D.; Pascual, M.A.; Savelli, L.; Epstein, E.; Van Holsbeke, C.; Guerriero, S.; Czekierdowski, A.; Zannoni, G.; Scambia, G.; Jurkovic, D.; Rossi, A.; Timmerman, D.; Valentin, L.; Testa, A.C. Imaging in gynecological disease (9): clinical and ultrasound characteristics of tubal cancer. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014, 43, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurman, R.J.; Shih, I.e.M. The Dualistic Model of Ovarian Carcinogenesis: Revisited, Revised, and Expanded. Am J Pathol. 2016, 186, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaerts, J.M.A.; Steenbeek, M.P.; van Bommel, M.H.D.; Bulten, J.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; de Hullu, J.A.; Simons, M. Recommendations for diagnosing STIC: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Virchows Arch. 2022, 480, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanciu, P.I.; Ind, T.E.J.; Barton, D.P.J.; Butler, J.B.; Vroobel, K.M.; Attygalle, A.D.; Nobbenhuis, M.A.E. Development of Peritoneal Carcinoma in women diagnosed with Serous Tubal Intraepithelial Carcinoma (STIC) following Risk-Reducing Salpingo-Oophorectomy (RRSO). J Ovarian Res. 2019, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, N.; Sessa, C.; du Bois, A.; Ledermann, J.; McCluggage, W.G.; McNeish, I.; Morice, P.; Pignata, S.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Vergote, I.; Baert, T.; Belaroussi, I.; Dashora, A.; Olbrecht, S.; Planchamp, F.; Querleu, D.; ESMO-ESGO Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference Working Group. ESMO-ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours and recurrent disease†. Ann Oncol. 2019, 30, 672–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, M.B.; Pal, T.; Maxwell, K.N.; Churpek, J.; Kohlmann, W.; AlHilli, Z.; Arun, B.; Buys, S.S.; Cheng, H.; Domchek, S.M.; Friedman, S.; Giri, V.; Goggins, M.; Hagemann, A.; Hendrix, A.; Hutton, M.L.; Karlan, B.Y.; Kassem, N.; Khan, S.; Khoury, K.; Kurian, A.W.; Laronga, C.; Mak, J.S.; Mansour, J.; McDonnell, K.; Menendez, C.S.; Merajver, S.D.; Norquist, B.S.; Offit, K.; Rash, D.; Reiser, G.; Senter-Jamieson, L.; Shannon, K.M.; Visvanathan, K.; Welborn, J.; Wick, M.J.; Wood, M.; Yurgelun, M.B.; Dwyer, M.A.; Darlow, S.D. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 2.2024. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023, 21, 1000–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corzo, C.; Iniesta, M.D.; Patrono, M.G.; Lu, K.H.; Ramirez, P.T. Role of Fallopian Tubes in the Development of Ovarian Cancer. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017, 24, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludovisi, M.; Bruno, M.; Capanna, G.; Di Florio, C.; Calvisi, G.; Guido, M. Sonographic features of pelvic tuberculosis mimicking ovarian-tubal-peritoneal carcinoma. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023, 61, 536–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, I.M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.L. The Origin of Ovarian Cancer Species and Precancerous Landscape. Am J Pathol. 2021, 191, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaerts, J.M.A.; van Bommel, M.H.D.; Hermens, R.P.M.G.; Steenbeek, M.P.; de Hullu, J.A.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; STIC consortium; Simons, M. Consensus based recommendations for the diagnosis of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: an international Delphi study. Histopathology. 2023, 83, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabban, J.T.; Garg, K.; Crawford, B.; Chen, L.M.; Zaloudek, C.J. Early detection of high-grade tubal serous carcinoma in women at low risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome by systematic examination of fallopian tubes incidentally removed during benign surgery. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014, 38, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.X.; Lu, Z.H.; Shen, K.; Cheng, W.J.; Malpica, A.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J.J.; Zhang, Z.H.; Liu, J. Advances in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: correlation with high grade serous carcinoma and ovarian carcinogenesis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014, 7, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patrono, M.G.; Iniesta, M.D.; Malpica, A.; Lu, K.H.; Fernandez, R.O.; Salvo, G.; Ramirez, P.T. Clinical outcomes in patients with isolated serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC): A comprehensive review. Gynecol Oncol. 2015, 139, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenbeek, M.P.; van Bommel, M.H.D.; Bulten, J.; Hulsmann, J.A.; Bogaerts, J.; Garcia, C.; Cun, H.T.; Lu, K.H.; van Beekhuizen, H.J.; Minig, L.; Gaarenstroom, K.N.; Nobbenhuis, M.; Krajc, M.; Rudaitis, V.; Norquist, B.M.; Swisher, E.M.; Mourits, M.J.E.; Massuger, L.F.A.G.; Hoogerbrugge, N.; Hermens, R.P.M.G.; IntHout, J.; de Hullu, J.A. Risk of Peritoneal Carcinomatosis After Risk-Reducing Salpingo-Oophorectomy: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2022, 40, 1879–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Ven, J.; Linz, V.C.; Anic, K.; Schmidt, M.W.; Loewe, A.; Krajnak, S.; Schmidt, M.; Kommoss, S.; Schmalfeldt, B.; Sehouli, J.; Hasenburg, A.; Battista, M.J. A questionnaire-based survey on the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for patients with STIC in Germany. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2023, 308, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongsong, T.; Wanapirak, C.; Tantipalakorn, C.; Tinnangwattana, D. Sonographic Diagnosis of Tubal Cancer with IOTA Simple Rules Plus Pattern Recognition. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 3011–3015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fedoua, W.; Mouna, H.; Hasana, S.; Boufettal, H.; Mahdaoui, S.; Samouh, N. Tubal adenocarcinoma: Report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023, 109, 108494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berek, J.S.; Renz, M.; Kehoe, S.; Kumar, L.; Friedlander, M. Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021, 155 (Suppl 1), 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onda, T.; Tanaka, Y.O.; Kitai, S.; Manabe, T.; Ishikawa, M.; Hasumi, Y.; Miyamoto, K.; Ogawa, G.; Satoh, T.; Saito, T.; Kasamatsu, T.; Nakanishi, T.; Japan Clinical Oncology Group. Stage III disease of ovarian, tubal and peritoneal cancers can be accurately diagnosed with pre-operative CT. Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG0602. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2021, 51, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howitt, B. E.; Hanamornroongruang, S.; Lin, D. I.; Conner, J. E.; Schulte, S.; Horowitz, N.; Crum, C.P.; Meserve, E.E. Evidence for a Dualistic Model of High-grade Serous Carcinoma. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology 2015, 39, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagotti, A.; Perelli, F.; Pedone, L.; Scambia, G. Current Recommendations for Minimally Invasive Surgical Staging in Ovarian Cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagotti, A.; Ferrandina, G.; Fanfani, F.; Garganese, G.; Vizzielli, G.; Carone, V.; Salerno, M.G.; Scambia, G. Prospective validation of a laparoscopic predictive model for optimal cytoreduction in advanced ovarian carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008, 199, 642.e1–642.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Sadiq, N.M. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Fallopian Tube. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Terada, K.Y.; Ahn, H.J.; Kessel, B. Differences in risk for type 1 and type 2 ovarian cancer in a large cancer screening trial. J Gynecol Oncol. 2016, 27, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvanathan, K.; Shaw, P.; May, B.J.; Bahadirli-Talbott, A.; Kaushiva, A.; Risch, H.; Narod, S.; Wang, T.L.; Parkash, V.; Vang, R.; Levine, D.A.; Soslow, R.; Kurman, R.; Shih, I.M. Fallopian Tube Lesions in Women at High Risk for Ovarian Cancer: A Multicenter Study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2018, 11, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, M.E.; Piedmonte, M.; Mai, P.L.; Ioffe, O.B.; Ronnett, B.M.; Van Le, L.; Ivanov, I.; Bell, M.C.; Blank, S.V.; DiSilvestro, P.; Hamilton, C.A.; Tewari, K.S.; Wakeley, K.; Kauff, N.D.; Yamada, S.D.; Rodriguez, G.; Skates, S.J.; Alberts, D.S.; Walker, J.L.; Minasian, L.; Lu, K.; Greene, M.H. Pathologic findings at risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy: primary results from Gynecologic Oncology Group Trial GOG-0199. J Clin Oncol. 2014, 32, 3275–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bommel, M.H.D.; Steenbeek, M.P.; IntHout, J.; Hermens, R.P.M.G.; Hoogerbrugge, N.; Harmsen, M.G.; van Doorn, H.C.; Mourits, M.J.E.; van Beurden, M.; Zweemer, R.P.; Gaarenstroom, K.N.; Slangen, B.F.M.; Brood-van Zanten, M.M.A.; Vos, M.C.; Piek, J.M.; van Lonkhuijzen, L.R.C.W.; Apperloo, M.J.A.; Coppus, S.F.P.J.; Prins, J.B.; Custers, J.A.E.; de Hullu, J.A. Cancer worry among BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant carriers choosing surgery to prevent tubal/ovarian cancer: course over time and associated factors. Support Care Cancer. 2022, 30, 3409–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry-Maharaj, A.; Glazer, C.; Burnell, M.; Ryan, A.; Berry, H.; Kalsi, J.; Woolas, R.; Skates, S.J.; Campbell, S.; Parmar, M.; Jacobs, I.; Menon, U. Changing trends in reproductive/lifestyle factors in UK women: descriptive study within the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). BMJ Open. 2017, 7, e011822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, T.; Belau, M.H.; von Grundherr, J.; Schlemmer, Z.; Patra, S.; Becher, H.; Schulz, K.H.; Zyriax, B.C.; Schmalfeldt, B.; Chang-Claude, J. Randomised controlled trial testing the feasibility of an exercise and nutrition intervention for patients with ovarian cancer during and after first-line chemotherapy (BENITA-study). BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e054091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.A.; Burnell, M.; Ryan, A.; Karpinskyj, C.; Kalsi, J.K.; Taylor, H.; Apostolidou, S.; Sharma, A.; Manchanda, R.; Woolas, R.; Campbell, S.; Parmar, M.; Singh, N.; Jacobs, I.J.; Menon, U.; Gentry-Maharaj, A. Association of hysterectomy and invasive epithelial ovarian and tubal cancer: a cohort study within UKCTOCS. BJOG. 2022, 129, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onda, T.; Satoh, T.; Saito, T.; Kasamatsu, T.; Nakanishi, T.; Nakamura, K.; Wakabayashi, M.; Takehara, K.; Saito, M.; Ushijima, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Kawana, K.; Yokota, H.; Takano, M.; Takeshima, N.; Watanabe, Y.; Yaegashi, N.; Konishi, I.; Kamura, T.; Yoshikawa, H.; Japan Clinical Oncology Group. Comparison of treatment invasiveness between upfront debulking surgery versus interval debulking surgery following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for stage III/IV ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal cancers in a phase III randomised trial: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG0602. Eur J Cancer. 2016, 64, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Onda, T.; Satoh, T.; Ogawa, G.; Saito, T.; Kasamatsu, T.; Nakanishi, T.; Mizutani, T.; Takehara, K.; Okamoto, A.; Ushijima, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Kawana, K.; Yokota, H.; Takano, M.; Kanao, H.; Watanabe, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Yaegashi, N.; Kamura, T.; Yoshikawa, H.; Japan Clinical Oncology Group. Comparison of survival between primary debulking surgery and neoadjuvant chemotherapy for stage III/IV ovarian, tubal and peritoneal cancers in phase III randomised trial. Eur J Cancer. 2020, 130, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouzier, R.; Gouy, S.; Selle, F.; Lambaudie, E.; Floquet, A.; Fourchotte, V.; Pomel, C.; Colombo, P.E.; Kalbacher, E.; Martin-Francoise, S.; Fauvet, R.; Follana, P.; Lesoin, A.; Lecuru, F.; Ghazi, Y.; Dupin, J.; Chereau, E.; Zohar, S.; Cottu, P.; Joly, F. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab-containing neoadjuvant therapy followed by interval debulking surgery in advanced ovarian cancer: Results from the ANTHALYA trial. Eur J Cancer. 2017, 70, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, U.; Gentry-Maharaj, A.; Burnell, M.; Ryan, A.; Kalsi, J.K.; Singh, N.; Dawnay, A.; Fallowfield, L.; McGuire, A.J.; Campbell, S.; Skates, S.J.; Parmar, M.; Jacobs, I.J. Mortality impact, risks, and benefits of general population screening for ovarian cancer: the UKCTOCS randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2023 May 11, 1–81. [CrossRef]

- Vizzielli, G.; Costantini, B.; Tortorella, L.; Pitruzzella, I.; Gallotta, V.; Fanfani, F.; Gueli Alletti, S.; Cosentino, F.; Nero, C.; Scambia, G.; Fagotti, A. A laparoscopic risk-adjusted model to predict major complications after primary debulking surgery in ovarian cancer: A single-institution assessment. Gynecol Oncol. 2016, 142, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).