Submitted:

16 July 2024

Posted:

17 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. A Legal Approach to the Problem

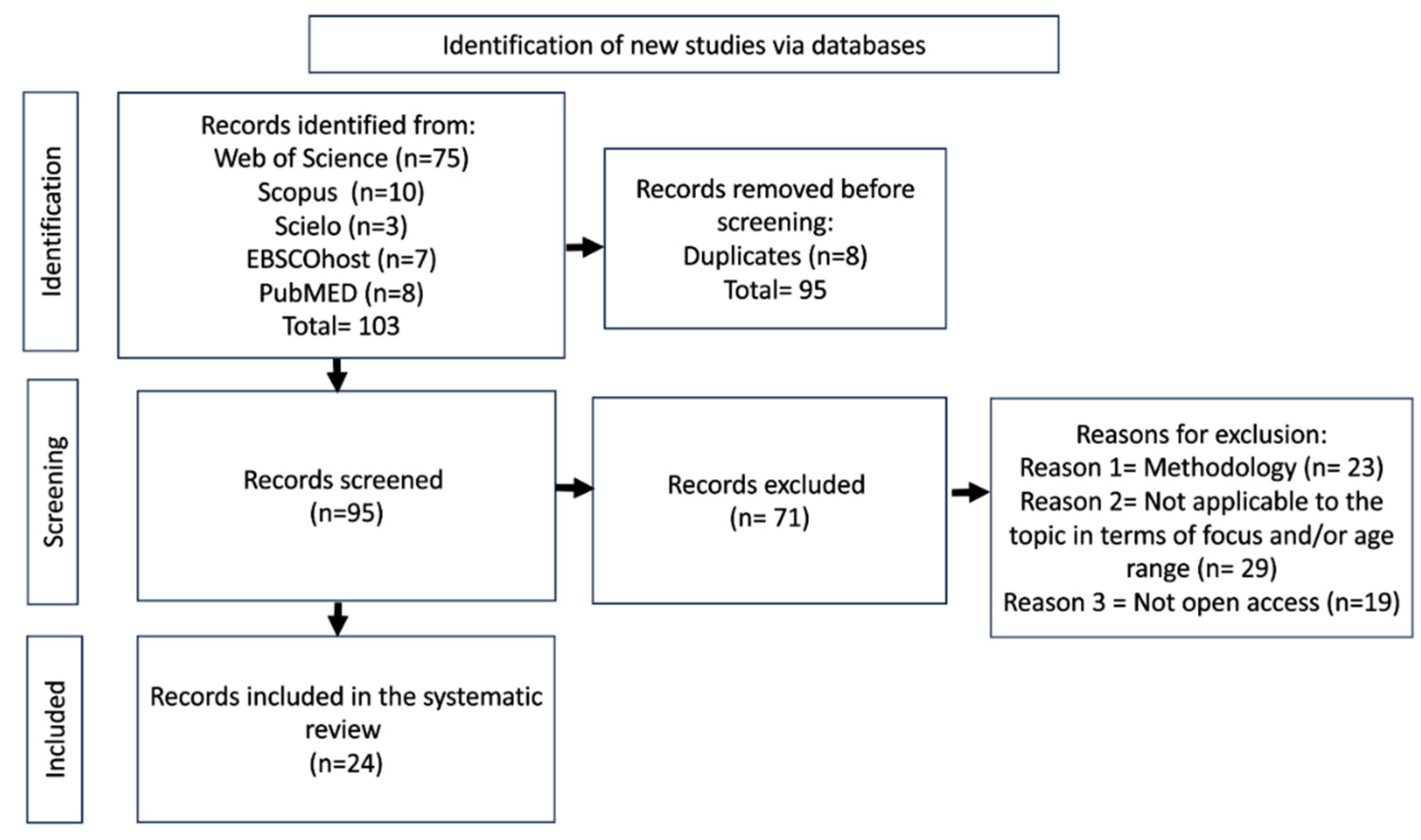

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Selection

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Article Characterization

3.2. Contents of the Selected Articles

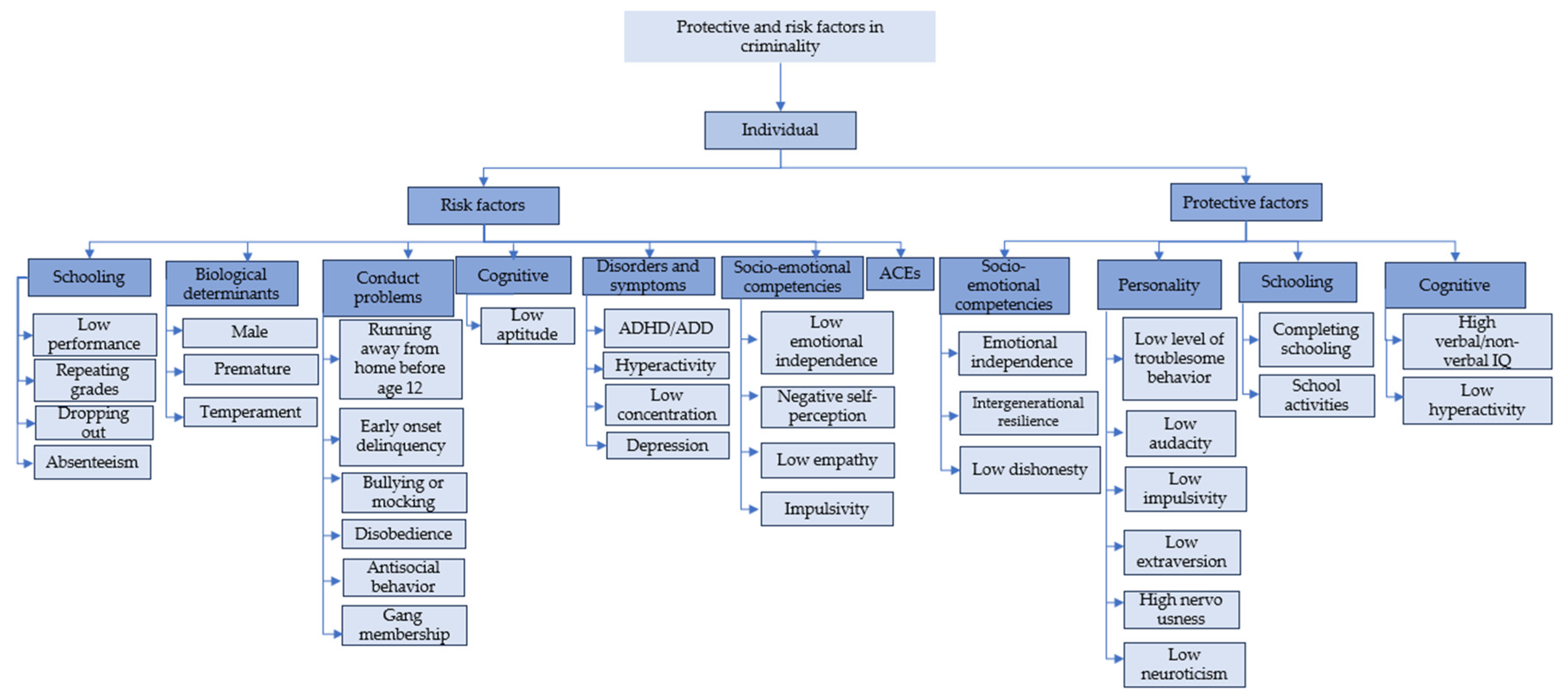

3.2.1. Individual Risk Factors

3.2.2. Individual Protective Factors

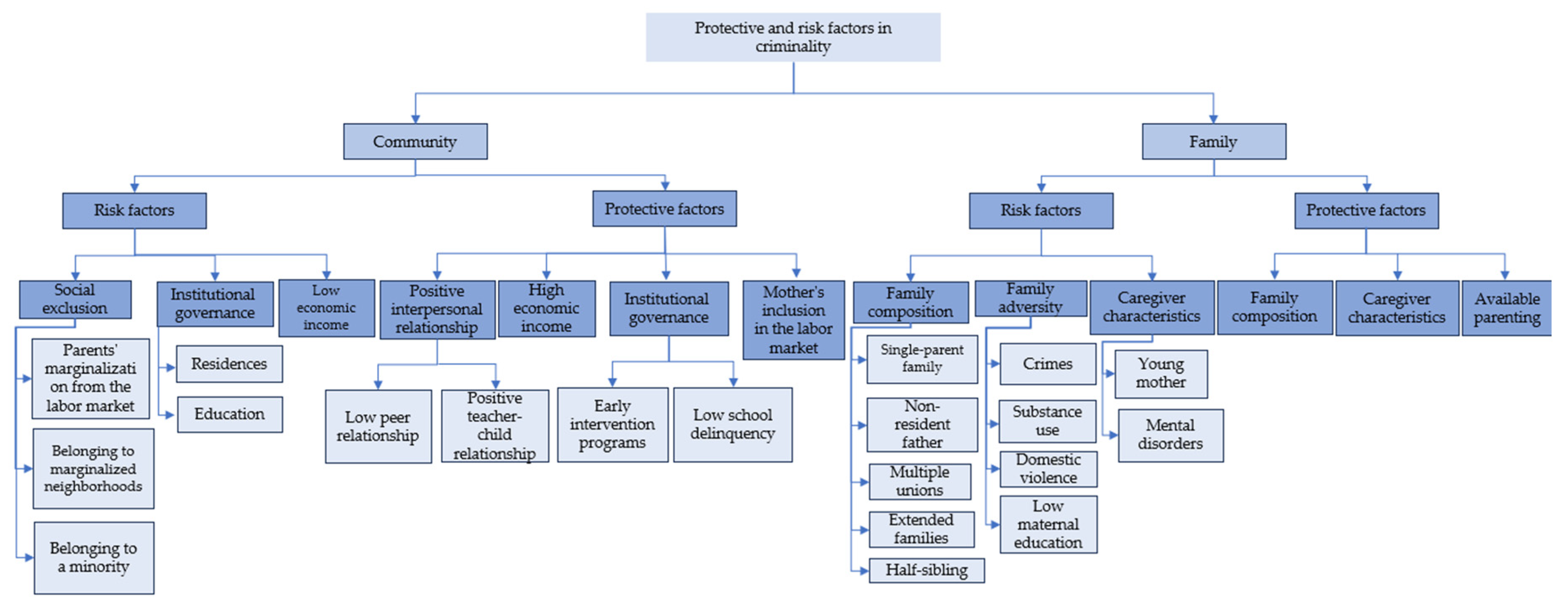

3.2.3. Family Risk Factors

3.2.4. Family Protective Factors

3.2.5. Community Risk Factors

3.2.6. Community Protective Factors

4. Discussion

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De la Peña, M., & Gómez, J. Agresión y conducta antisocial en la adolescencia: una integración conceptual. Psicopatología Clínica Legal y Forense. 2006, 6, 9-24. ISSN 1576-9941.

- Milano, W. Entre la psicología criminal, la psicología forense y la psicología penitenciaria. Ciencia Digital, 2019, 3, 23-39. [CrossRef]

- Verde, M., & Roca, D. Psicología criminal; Cañizal, A. & Bazaco, E., Eds.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Madrid, España, 2006; ISBN 978-84-8322-306-2.

- Carreón, W. Criminología del Desarrollo: estudio del desarrollo en la formación de la conducta criminal. Ratio Juris UNAULA 2023, 18, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, T. & Farrington, D. Developmental and Life-Course Explanations of Offending. Psychology, Crime & Law. 2018; 25, 609–625. [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D., Ttofi, M. & Piquero, A. Risk, promotive, and protective factors in youth offending: Results from the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2016; 45, 63–70. [CrossRef]

- Loeber, R., Farrington, D. & Waschbusch, D. Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions, Loeber, R & Farrington, D., Ed.; Thousand Oaks: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; 313–345ISBN 978-14-5224-374-0.

- Moffitt, T. Adolescence limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review 1993, 100, 674–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrington, D. The School Years: Current issues in the socialization of young people Chapter 6: Juvenile Delinquency, 2nd ed.; Coleman, J., Ed.; Routledge, London, UK, 1992a; pp. 123–163. ISBN: 9780415061704.

- Farrington, D. Criminal career research in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Criminology, 1992b; 32, 521– 536. [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, M. & Trudeau Le Blanc, P. La réadaptation de l’adolescent antisocial: Un programme cognitivo-émotivo-comportemental. Presses de l’Université de Montréal, Montreal, Canada, 2014. ISBN: 9782760633537.

- Farrington, D., Kazemian, L. & Piquero, A. The Oxford handbook of developmental and life-course criminology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2019, ISBN: 9780190201388.

- McAra, L., & McVie, S. Developmental and life-course criminology: innovations, impacts, and applications, 6th ed; Liebling, A., Maruna, S. & McAra, L., Eds.; Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2017. ISBN: 9780190201371.

- McGee, T. & Farrington, D. Handbook of Criminological Theory. Piquero, A., Ed.; Wiley- Blackwell, Chinchester, UK, 2016, pp. 336-354, ISBN: 978-0190201371.

- Farrington, D. Integrated Developmental and Life-Course Theories of Offending: Advances in Criminological Theory. Farrington, D., Ed.; Transaction Publisher, New York, USA, 2005; Volume 4, pp. 73-92. ISBN: 9871412807999.

- Catalano, R., Hawkins, J., Kosterman, R., Bailey, J., Oesterle, S., Cambron, C. & Farrington, D. Applying the social development model in middle childhood to promote healthy development: Effects from primary school through the 30s and across generations. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology. 2021, 7, 66-86. [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T. Life-course persistent versus adolescence limited antisocial behavior. In Developmental Psychopathology; Cicchetti, D. & Cohen, D, Wiley: USA, 2006; pp. 570–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R. & Laub, J. Desistance from crime over the life course. In Handbook of the life course, Springer US: Boston, 2003, pp. 295-309. [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R. & Laub, J. Life-Course and Developmental Criminology: Looking back, moving forward. ASC Division of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology inaugural David P. Farrington lecture, 2017. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology. 2020, 6, 158-171. [CrossRef]

- Wikström, P., & Treiber, K. What drives persistent offending? The neglected and unexplored role of the social environment. In The development of persistent criminality; Savage, J, Ed.; Oxford University Press: United Kingdom, 2009, pp. 389-420. ISBN 9780190295004.

- Wikström, P., & Treiber, K. The Dynamics of Change: Criminogenic Interactions and Life-Course Patterns in Crime. In The Oxford handbook of developmental and life-course criminology. Farrington, D., Kazemian, L. & Piquero, A, Eds.; Oxford University Press: United Kingdom, 2019, pp. 272-294.

- 22. Thornberry, T., & Krohn, M. Applying Interactional Theory to the explanation of continuity and change in antisocial behaviour. In Integrated Developmental and Life-Course Theories of Offending; Farrington, D, Ed.; Transaction Publishers: USA, 2005, pp. 183-209.

- Thornberry, T., & Krohn, M. Interactional Theory. In The Oxford handbook of developmental and life-course criminology; Farrington, D., Kazemian, L. & Piquero, A, Eds.; Oxford University Press: United Kingdom, 2019, pp. 248-271.

- Requena, L. Principios generales de criminología del desarrollo y las carreras criminales; JM Bosch: España, 2014; pp. 11-104.

- Faas, A. E. Psicología del desarrollo de la niñez; Editorial Brujas: Córdoba, Argentina, 2018; pp. 13–417. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, D. The Development of Offending and Antisocial Behavior from Childhood: Key Findings from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. J. Child Psychol, psychiat. 1995, 360, 929-964.

- Schneider, F. Measuring the Size and Development of the Shadow Economy. Can the Causes be Found and the Obstacles be Overcome?. In Essays on Economic Psychology; Brandstätter, H &, Güth, W, Eds.; Springer: Alemania, 1994, pp. 193-212.

- Meza-Lopehandía, M. Niños, niñas y adolescentes: La nomenclatura en proyecto de ley que crea el Servicio de Reinserción Juvenil a la luz del derecho internacional y nacional, 2020, Biblioteca Congreso Nacional de Chile.

- Aedo, M. y Varela, P. Algunas reflexiones sobre las diferencias de género en las conductas infractoras de niñas y adolescentes en Chile. Oñati Socio-Legal Serie. 2020, 10, 218-242.

- Pérez-Luco, R., Alarcón, P., Zambrano, A., Alarcón, M., Chesta, S. & Wegner, L. Taxonomía de la delincuencia adolescente con base en evidencia chilena. In Psicología Jurídica, conocimiento y práctica; Bringas, C. & Novo, M, Ed.; Sociedad Española de Psicología Jurídica y Forense: España, 2017, pp. 259-268.

- Tremblay, R. Early development of physical aggression and early risk factors for chronic physical aggression in humans. In Neuroscience of aggression; Miczek, K & A. Meyer-Lindenberg, A, Eds.; Springer-Verlag Publishing: USA, 2014, pp. 315-327.

- Molinedo-Quílez, M. Factores de riesgo psicosociales en menores infractores. Revista española de sanidad penitenciaria. 2020, 22, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, C. Predicción y prevención de la delincuencia juvenil según las teorías del desarrollo social (social development theories). Revista de Derecho. 2003, 14, 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Maggi, S., Zaccaria, V., Breda, M., Romani, M., Aceti, F., Giacchetti, N., Ardizzone, I. y Sogos, C. A Narrative Review about Prosocial and Antisocial Behavior in Childhood: The Relationship with Shame and Moral Development. Children. 2022, 9, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Morizot, J. The contribution of temperament and personality traits to criminal and antisocial behavior development and desistance. In The Development of Criminal and Antisocial Behavior; J. Morizot & L. Kazemian, Eds.; Springer International Publishing: USA, 2015, pp. 137–165. [CrossRef]

- Senado de Chile. Boletín N° 14.959-07. https://www.senado.cl/appsenado/templates/tramitacion/index.php?boletin_ini=14559-07.

- Cousiño, L. Delincuencia Juvenil. In Clásicos de la literatura penal en Chile. La Revista de Ciencias Penales en el siglo XX: 1935-1995; Londoño, F. & Maldonado, F., Tirant Lo Blanch: Chile, 2018, p. 932.

- Estrada, F. Principios del procedimiento de aplicación de medidas de protección de derechos de niños y niñas. Revista de Derecho. 2015, 8, 84–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos Ortiz, L.T. La responsabilidad penal para adolescentes: un sistema entre la zanahoria y el garrote. Derecho Penal y Criminología. 2022, 43, 229-266. [CrossRef]

- Garland, D. Castigo y sociedad moderna., 2nd ed.; Editorial Siglo XXI: Mexico, 1999; pp. 321–339. [Google Scholar]

- De Geest, G. & Dari-Mattiacci, G. The Rise of Carrots and the Decline of Sticks. University of Chicago Law Review. 2013, 80, 341-393. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41825878.

- Cancian, M., Meyer D. & Wood R. Do Carrots Work Better than Sticks? Results from the National Child Support Noncustodial Parent Employment Demonstration. Journal of Policy Analysis and Managment. 2022; 41, 552–578. [CrossRef]

- Adolf, S. Utilidad y revisión de literatura. Revista de enfermería. 2015, 9, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes-Nuñez, J., Urrutia, G., Romero-García, M. & Alonso-Fernández, S. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790-799. [CrossRef]

- Koegl, C., Farrington, D. & Augimeri, L. Predicting Future Criminal Convictions of Children Under Age 12 Using the Early Assessment Risk Lists. Journal of Developmental and Life-course criminology. 2021, 7, 17-40. [CrossRef]

- Basto-Pereira, M., & Farrington, D. Advancing knowledge about lifelong crime sequences. The British Journal of Criminology. 2019, 59, 354-377. [CrossRef]

- Whitten, T., McGee, T., Homel, R., Farrington, D. & Ttofi, M. Comparing The Criminal Careers and Childhood Risk Factors of Persistent, Chronic, and Persistent- Chronic Offenders. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 2019, 52, 151-173. [CrossRef]

- Martins, R., Gonçalves, H., Blumenberg, C., Könsgen, B., Houvèssou, G., Carone, C. & Murray, J. School performance and young adult crime in a Brazilian birth cohort. Journal of developmental and life-course criminology. 2022, 8, 647-668. [CrossRef]

- Gushue, K., Mccuish, E. & Corrado, R. Developmental Offending Patterns: Female Offending Beyond the Reference Category. Criminal justice and Behavior. 2021, 48, 139-156. [CrossRef]

- Van Hazebroek, B., Blokland, A., Wermink, H., De Keijser, J., Popma, A., & Van Domburgh, L. Delinquent development among early-onset offenders: Identifying and characterizing trajectories based on frequency across types of offending. Criminal justice and behavior. 2019, 46, 1542-1565. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, K., Baglivio, M., Vaughn, M., DeLisi, M. & Piquero, A. For males only? The search for serious, violent, and chronic female juvenile offenders. Journal of developmental and life-course criminology. 2017, 3, 168-195. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, V. & Stuewig, J. Gender differences in pathways to delinquency: The impact of family relationships and adolescent depression. Journal of Developmental and Life- Course Criminology. 2017, 3, 221-240. [CrossRef]

- Givens, E., & Reid, J. Developmental Trajectories of Physical Aggression and Nonaggressive Rule-Breaking During Late Childhood and Early Adolescence. Criminal justice and Behavior. 2019, 46, 395-414. [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales; Editorial Médica Panamericana: USA, 2013.

- Han, S. & Park, Y. Which risk factors plays the most critical role for delinquent behavior? Examining integrated cognitive antisocial potencial theory. Crime & Delinquency. 2023, 69, 1947-1972. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S., Savolainen, J., Mason, W., Miettunen, J., January, S. & Järvelin, M. Does educational marginalization mediate the path from childhood cumulative risk to criminal offending?. Journal of developmental and life-course criminology. 2017, 3, 326-346. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., McCuish, E. & Corrado, R. Is the Foster Care-Crime Relationship a Consequence of Exposure? Examining Potential Moderating Factors. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2021, 19, 94-112. [CrossRef]

- Basto-Pereira, M. & Farrington, D. Lifelong conviction pathways and self-reported offending: towards a Deeper comprehension of criminal career development. The British Journal of Criminology. 2020, 60, 285-302. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, M., Fox, B. and Jennings, W. Do Developmental and Life-Course Theory Risk Factors Equally Predict Age of Onset Among Juvenile Sexual and Nonsexual Offenders?. Sexual Abuse. 2020, 32, 55-78. [CrossRef]

- Fox, B., Kortright, K., Gill, L., Oramas, D., Moule, R. & Verona, E. Heterogeneity in the Continuity and Change of Early and Adult Risk factor Profiles of Incarcerated Individuals: A latent Transition Analysis. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2021, 19, 68-93. [CrossRef]

- Craig, J., Piquero, A., Farrington, D. & Ttofi, M. A little early risk goes a long bad way: Adverse childhood experiences and life-course offending in the Cambridge study. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2017, 53, 34- 45. [CrossRef]

- Thornberry, T. Intergenerational Patterns in Offending: Lessons from the Rochester Intergenerational study-ASC Division of Developmental and Life Course Criminology David P. Farrington Lecture, 2019. Journal of Developmental and Life- Course Criminology. 2020, 6, 381-397. [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, D., Wiesner, M., Kerr, D., Owen, L. & Tiberio, S. Intergenerational associations in crime for an at-risk sample of US men: Factors that may mitigate or exacerbate transmission. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology. 2021, 7, 331-358. [CrossRef]

- Neaverson, A., Murray, A., Ribeaud, D. & Eisner, M. Disrupting the Link Between Corporal Punishment Exposure and Adolescent Aggression: The Role of Teacher- child Relationships. Journal of youth and adolescence. 2022, 51, 2265-2280. [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D. Childhood Risk Factors for Criminal Career Duration: Comparisons with Prevalence, Onset, Frequency and Recidivism. Criminal behaviour and mental health. 2020, 30, 159-171. [CrossRef]

- Valdivia-Devia, M., Oyanedel, J. & Andrés-Pueyo, A. Trayectoria y reincidencia criminal. Revista Criminalidad. 2018, 60, 251-267. ISSN-e 1794-3108.

- Andolfi, M. El niño consultante. Cahiers critiques de therapie familial et des pratiques de reseaux. 2001, 2, 99-116.

- Barudy, J. Dolor invisible de la infancia, Paidós: España, 1998.

- Ortega, B., Jimeno, M. V., Topino, E., & Latorre, J. M. Direct and indirect childhood victimization and their influence on the development of adolescents antisocial behaviors. Psychological trauma: theory, research, practice, and policy. 2023, 16, 72–80. [CrossRef]

- Chopin, J., Fortin, F., & Paquette, S. Childhood victimization and poly-victimization of online sexual offenders: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Child Abuse & Neglect..2022, 129, 105-659. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, K. T., Cuevas, C., Intravia, J., Baglivio, M. T., & Epps, N. The effects of neighborhood context on exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACE) among adolescents involved in the juvenile justice system: Latent classes and contextual effects. Journal of youth and adolescence. 2018, 47, 2279-2300. [CrossRef]

- Miley, L., Fox, B., Muniz, C., Perkins, R., & DeLisi, M. Does childhood victimization predict specific adolescent offending? An analysis of generality versus specificity in the victim-offender overlap. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020, 101, 2–12. [CrossRef]

- Hein, A. Factores de riesgo y delincuencia juvenil: revisión de la literatura nacional e internacional. Fundación Paz Ciudadana. 2004, 1-21.

- Berg M. & Mulford C. Reappraising and redirecting research on the victim-offender overlap. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2020, 21, 16–30. [CrossRef]

- Kushner M., Botchkovar E., Antonaccio O., & Hughes L. Exploring vulnerability to deviant coping among victims of crime in two Post-Soviet cities. Justice Quarterly. 2020 38, 1182–1209. [CrossRef]

- Kushner, M. Betrayal Trauma and Gender: An Examination of the Victim-Offender Overlap. Journal of interpersonal violence. 2022, 37, NP3750–NP3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Costa, E., Faúndes, A., & Nunes, R. The association between victim-offender relationship and the age of children and adolescents who suffer sexual violence: a cross-sectional study. Jornal de pediatria. 2022, 98, 310–315. [CrossRef]

- Beckley, A., Caspi, A., Arseneault, L., Barnes, J., Fisher, H., Harrington, H., Moffitt, T. The Developmental Nature of the Victim-Offender Overlap. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology. 2017, 4, 24–49. [CrossRef]

- Silva, C., Moreira, P., Moreira, D., Rafael, F., Rodrigues, A., Leite, A., Lopes, S. y Moreira, D. Impact of adverse Childhood Experiences in Young Adults and Adults: A Systematic Literature Review. Pediatric Reports. 2024, 16, 461-481. [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, P., Luco, R., Chesta, S. & Wenger, L. Examinando factores de riesgo y recursos para la intervención con adolescentes infractores. In Psicología Jurídica, conocimiento y práctica; Bringas, C. & Novo, M, Ed.; Sociedad Española de Psicología Jurídica y Forense: España, 2017, pp. 425-442. ISBN 978-84-8408-326-9.

- Zambrano, V., Gemignani, M., Fernández-Pacheco, G., & Ergas, L. Resiliencia en adolescentes infractores con trayectorias en los sistemas chilenos de bienestar infantil y de justicia adolescente. Revista de Estudios Sociales. 2024, 88, 59–78. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, J., Garrido, Á., & Henríquez, S. Trayectorias de vida de jóvenes infractores de ley internados y respuesta educativa en el servicio nacional de menores de Chile. Interciencia, 2022, 47, 191-198. ISSN 0378-1844.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).