Submitted:

16 July 2024

Posted:

18 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Terminology

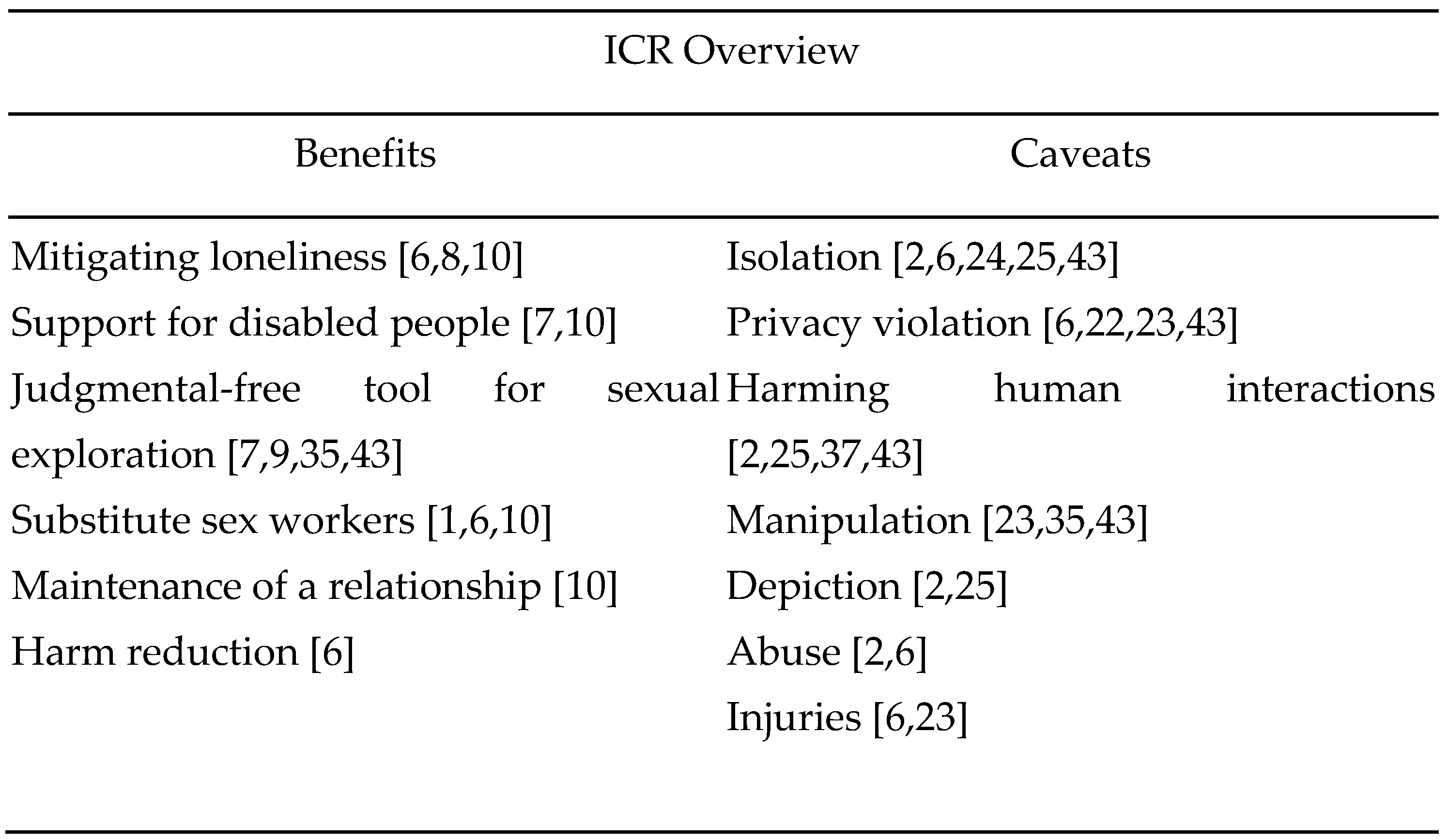

3. Perceived Benefits of ICR

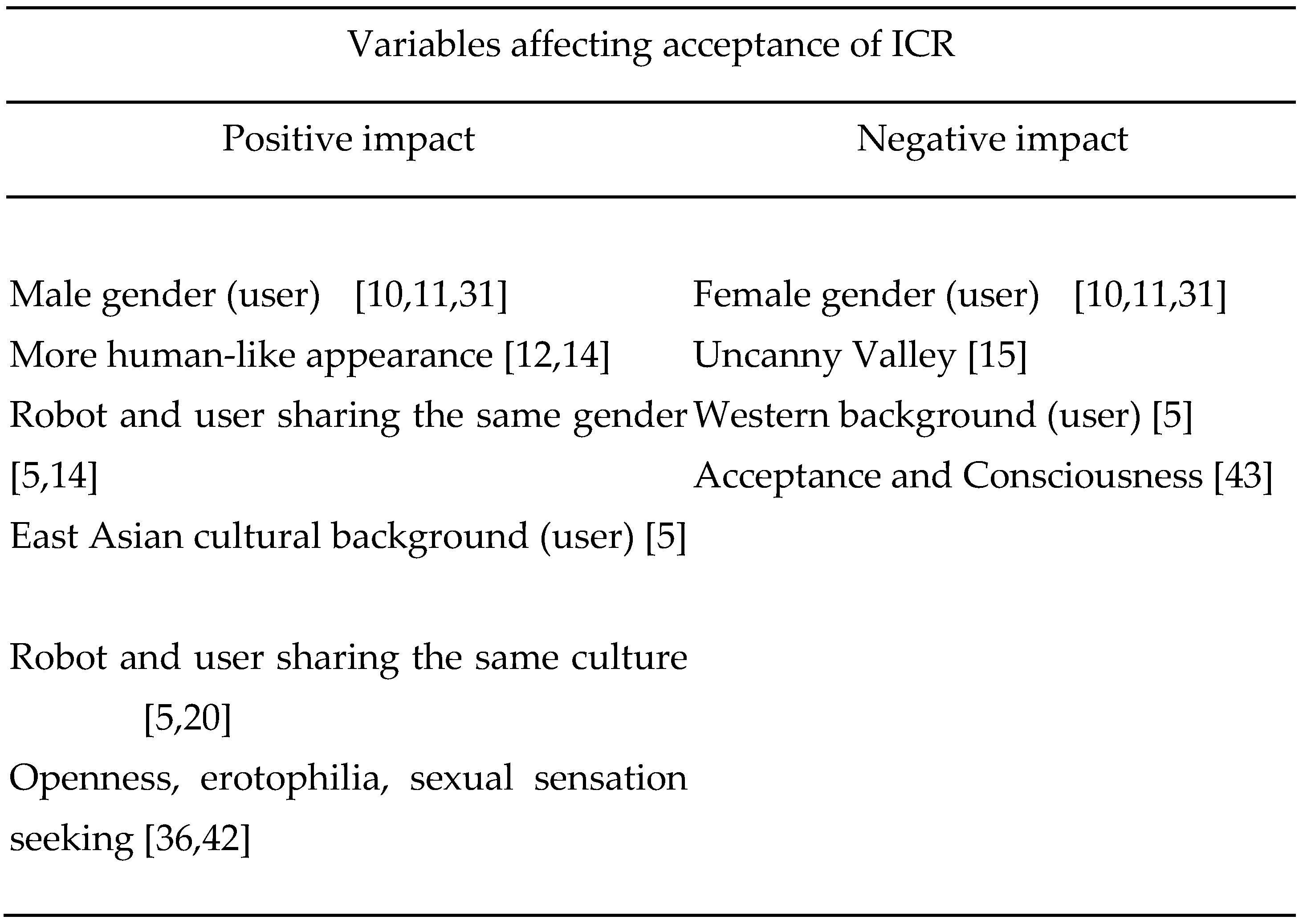

4. Acceptance and Intimacy of ICR

4.1. Robot and User Characteristics

4.2. Robotic Touch

4.3. Cultural Influences in ICR Acceptability

5. Possible Caveats of ICRs

5.1. Technological Implications

5.2. Psychological and Behavioral Implications of ICR Use

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Levy, "Love and sex with robots: The evolution of human-robot relationships," New York, 2009, p. 352.

- N. Massa, P. Bisconti, and D. Nardi, "The psychological implications of companion robots: a theoretical framework and an experimental setup," International Journal of Social Robotics, vol. 15, no. 12, pp. 2101-2114, 2023.

- World Health Organization, "Social isolation and loneliness among older people: advocacy brief," 2021.

- J. M. Twenge, J. Haidt, A. B. Blake, C. McAllister, H. Lemon, and A. Le Roy, "Worldwide increases in adolescent loneliness," Journal of Adolescence, vol. 93, pp. 257-269, 2021.

- R. Moberg and A. Khan, "Humanoid Robot Acceptance: A Concise Review of Literature," in 2022 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), 2022, pp. 1223-1228.

- K. R. Hanson and C. C. Locatelli, "From sex dolls to sex robots and beyond: A narrative review of theoretical and empirical research on human-like and personified sex tech," Current Sexual Health Reports, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 106-117, 2022.

- E. Fosch-Villaronga and A. Poulsen, "Sex robots in care: Setting the stage for a discussion on the potential use of sexual robot technologies for persons with disabilities," in Companion of the 2021 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Mar. 2021, pp. 1-9.

- H. Robinson, B. MacDonald, N. Kerse, and E. Broadbent, "The psychosocial effects of a companion robot: a randomized controlled trial," Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, vol. 14, no. 9, pp. 661-667, 2013.

- Bianchi, “Considering sex robots for older adults with cognitive impairments”. Journal of medical ethics, vol. 47, no 1, pp. 37-38, 2021.

- M. Scheutz and T. Arnold, "Are we ready for sex robots?," in 2016 11th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), March 2016, pp. 351-358. [CrossRef]

- M. Nordmo, J. Ø. Næss, M. F. Husøy, and M. N. Arnestad, "Friends, lovers or nothing: Men and women differ in their perceptions of sex robots and platonic love robots," Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 11, 2020, Article 501020. [CrossRef]

- Edirisinghe, A. D. Cheok, and N. Khougali, "Perceptions and Responsiveness to Intimacy with Robots; A User Evaluation," Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 10715, pp. 138-157, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. K. Rempel, J. G. Holmes, and M. P. Zanna, "Trust in close relationships," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 49, no. 1, p. 95, 1985.

- X. Zheng, M. Shiomi, T. Minato, and H. Ishiguro, "How can Robots make people feel intimacy through Touch?," Journal of Robotics and Mechatronics, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 51-58, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Mori, K. F. MacDorman, and N. Kageki, "The uncanny valley [from the field]," IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 98-100, June 2012.

- J. Willemse, A. Toet, and J. B. Van Erp, "Affective and behavioral responses to robot-initiated social touch: toward understanding the opportunities and limitations of physical contact in human–robot interaction," Frontiers in ICT, vol. 4, Article 12, 2017. [Online]. Available: . [CrossRef]

- Collins English Dictionary, "Waifu," Accessed: 10-Jun-2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/waifu.

- Sakura, "Robot and ukiyo-e: implications to cultural varieties in human–robot relationships," AI & Soc, vol. 37, pp. 1563–1573, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Castelo and M. Sarvary, "Cross-cultural differences in comfort with humanlike robots," International Journal of Social Robotics, vol. 14, no. 8, pp. 1865-1873, 2022.

- V. Lim, M. Rooksby, and E. S. Cross, "Social robots on a global stage: establishing a role for culture during human–robot interaction," International Journal of Social Robotics, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 1307-1333, 2021.

- P. Mundy and W. Jarrold, "Infant joint attention, neural networks and social cognition," Neural Networks, vol. 23, no. 8-9, pp. 985-997, 2010.

- Bendel, "Love dolls and sex robots in unproven and unexplored fields of application," Paladyn, Journal of Behavioral Robotics, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1-12, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Galaitsi, C. O. Hendren, B. Trump, and I. Linkov, "Sex robots—a harbinger for emerging AI risk," Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, vol. 2, p. 27, 2019.

- N. Döring and S. Pöschl, "Sex toys, sex dolls, sex robots: Our under-researched bed-fellows," Sexologies, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. e51-e55, 2018.

- J. Borenstein and R. Arkin, "Robots, ethics, and intimacy: the need for scientific research," in On the Cognitive, Ethical, and Scientific Dimensions of Artificial Intelligence: Themes from IACAP 2016, 2019, pp. 299-309.

- S. Nyholm and L. E. Frank, "It loves me, it loves me not: Is it morally problematic to design sex robots that appear to love their owners?" Techne: Research in Philosophy & Technology, vol. 23, no. 3, 2019.

- K. Winkle and N. Mulvihill, "Anticipating the Use of Robots in Domestic Abuse: A Typology of Robot Facilitated Abuse to Support Risk Assessment and Mitigation in Human-Robot Interaction," in Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 2024, pp. 781-790.

- Marečková et al., “Men with Paraphilic Interests and Their Desire to Interact with a Sex Robot,” 1 Jan. 2022, pp. 39-48.

- G. Ara, S. Veggi, and D. P. Farrington, "Sexbots as Synthetic Companions: Comparing Attitudes of Official Sex Offenders and Non-Offenders," Int. J. Soc. Robotics, vol. 14, pp. 479–498, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Uluer, H. Kose, B. K. Oz, T. C. Aydinalev, and D. E. Barkana, "Towards an affective robot companion for audiology rehabilitation: How does pepper feel today?," in 2020 29th IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 2020, pp. 567-572.

- Kuo, J. M. Rabindran, E. Broadbent, Y. I. Lee, N. Kerse, R. M. Stafford, and B. A. MacDonald, "Age and gender factors in user acceptance of healthcare robots," in RO-MAN 2009 - The 18th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, 2009, pp. 214-219.

- W. Johal, S. Pesty, and G. Calvary, "Towards companion robots behaving with style," in The 23rd IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, 2014, pp. 1063-1068.

- S. Alesich and M. Rigby, "Gendered robots: Implications for our humanoid future," IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 50-59, 2017.

- Hancock, "Should society accept sex robots? Changing my perspective on sex robots through researching the future of intimacy," Paladyn, Journal of Behavioral Robotics, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 428-442, 2020.

- Koumpis and T. Gees, "Sex with robots: a not-so-niche market for disabled and older persons," Paladyn, Journal of Behavioral Robotics, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 228-232, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Dubé, M. Santaguida, C. Y. Zhu, S. Di Tomasso, R. Hu, G. Cormier, and D. Vachon, "Sex robots and personality: It is more about sex than robots," Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 136, p. 107403, 2022.

- N. J. Rothstein, D. H. Connolly, E. J. de Visser, and E. Phillips, "Perceptions of infidelity with sex robots," in Proceedings of the 2021 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 2021, pp. 129-139.

- M. Appel, C. Marker, and M. Mara, "Otakuism and the appeal of sex robots," Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 10, p. 569, 2019.

- M. Buss and M. Haselton, "The evolution of jealousy," Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 9, no. 11, pp. 506-506, 2005.

- D. Fincham and R. W. May, "Infidelity in romantic relationships," Current Opinion in Psychology, vol. 13, pp. 70-74, 2017.

- T. Oleksy and A. Wnuk, "Do women perceive sex robots as threatening? The role of political views and presenting the robot as a female-vs male-friendly product," Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 117, p. 106664, 2021.

- Z. Deniztoker, "Lovotics and the big-five: An exploration of the psychology of human-robot intimacy," in 7th International Student Research Conference - ISRC, Prague, Czech Republic, 2019.

- S. Dubé and D. Anctil, "Foundations of Erobotics," International Journal of Social Robotics, vol. 13, pp. 1205-1233, 2021. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).