Submitted:

17 July 2024

Posted:

18 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

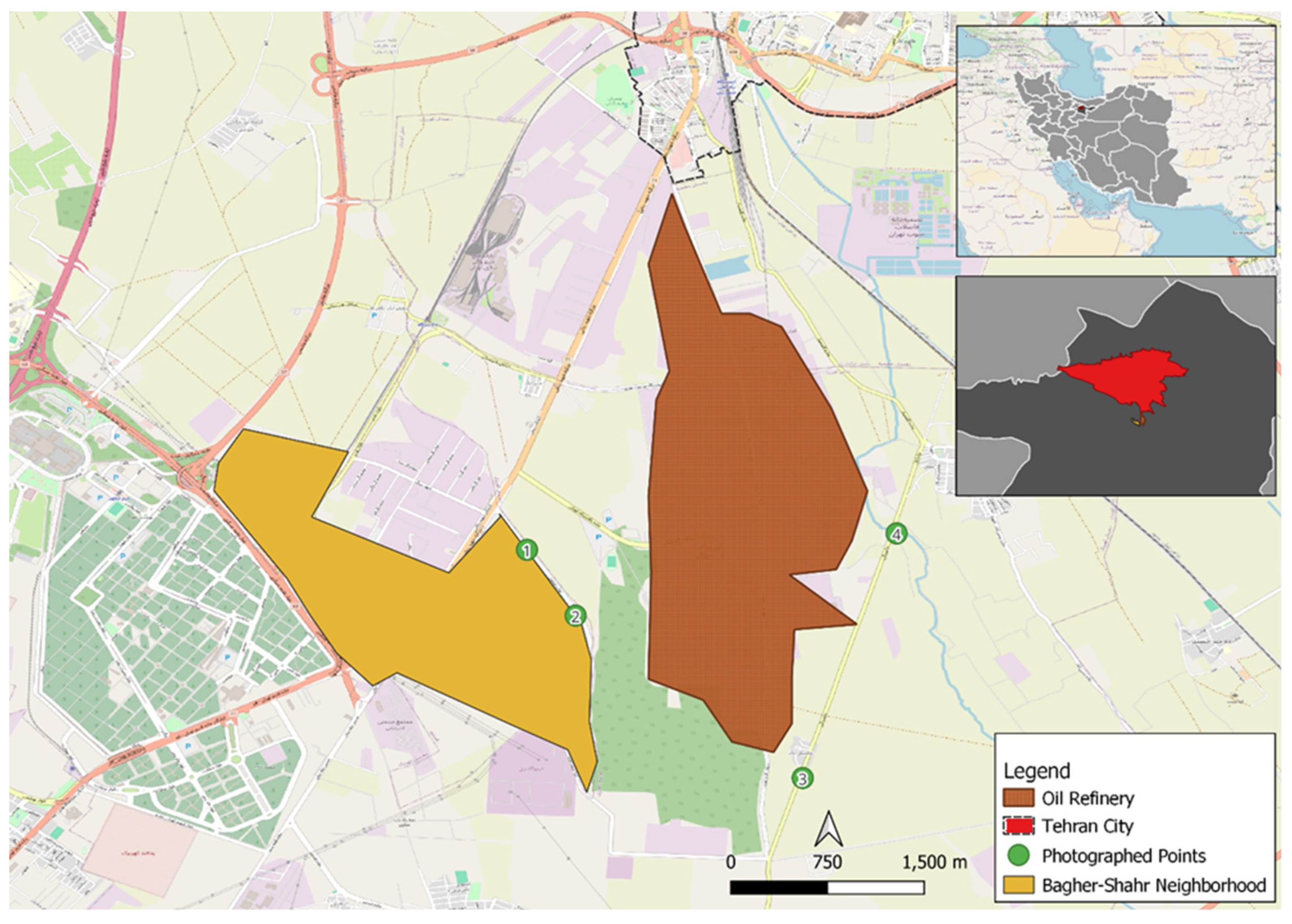

- To assess landscape values perception at the Tehran oil refinery.

- To examine the relationship between landscape values perception and stress levels at the Tehran oil refinery.

2. Materials and Methods

Design of the Survey

- How often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?

- How often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems?

- How often have you felt that things were going your way?

- How often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?

- Anxious/Serene

- Restless/Tranquil

- Tense/Calm

3. Results

Social- Demographic Findings

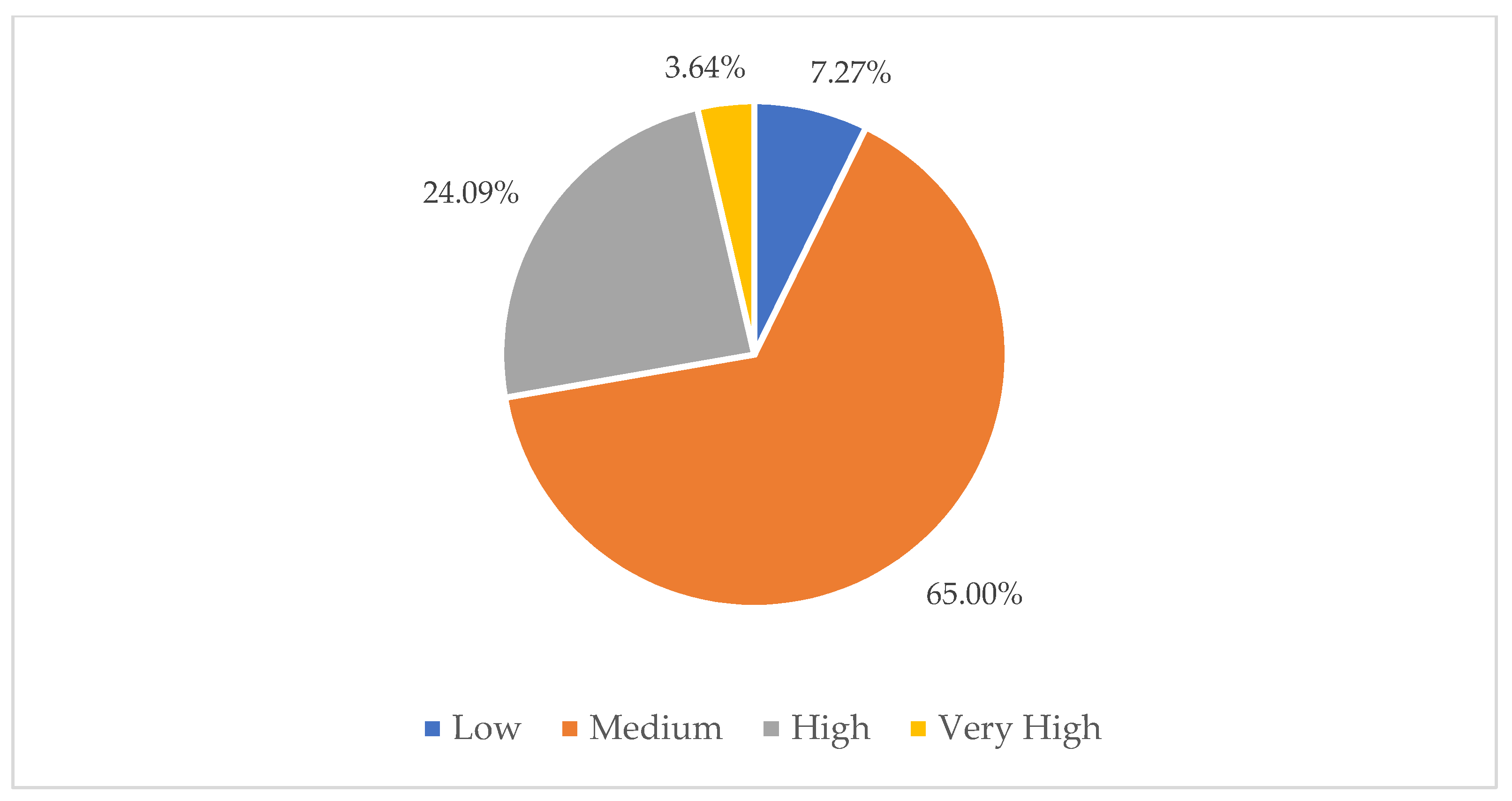

Perceived Stress Scale

Landscape Values Perception Findings

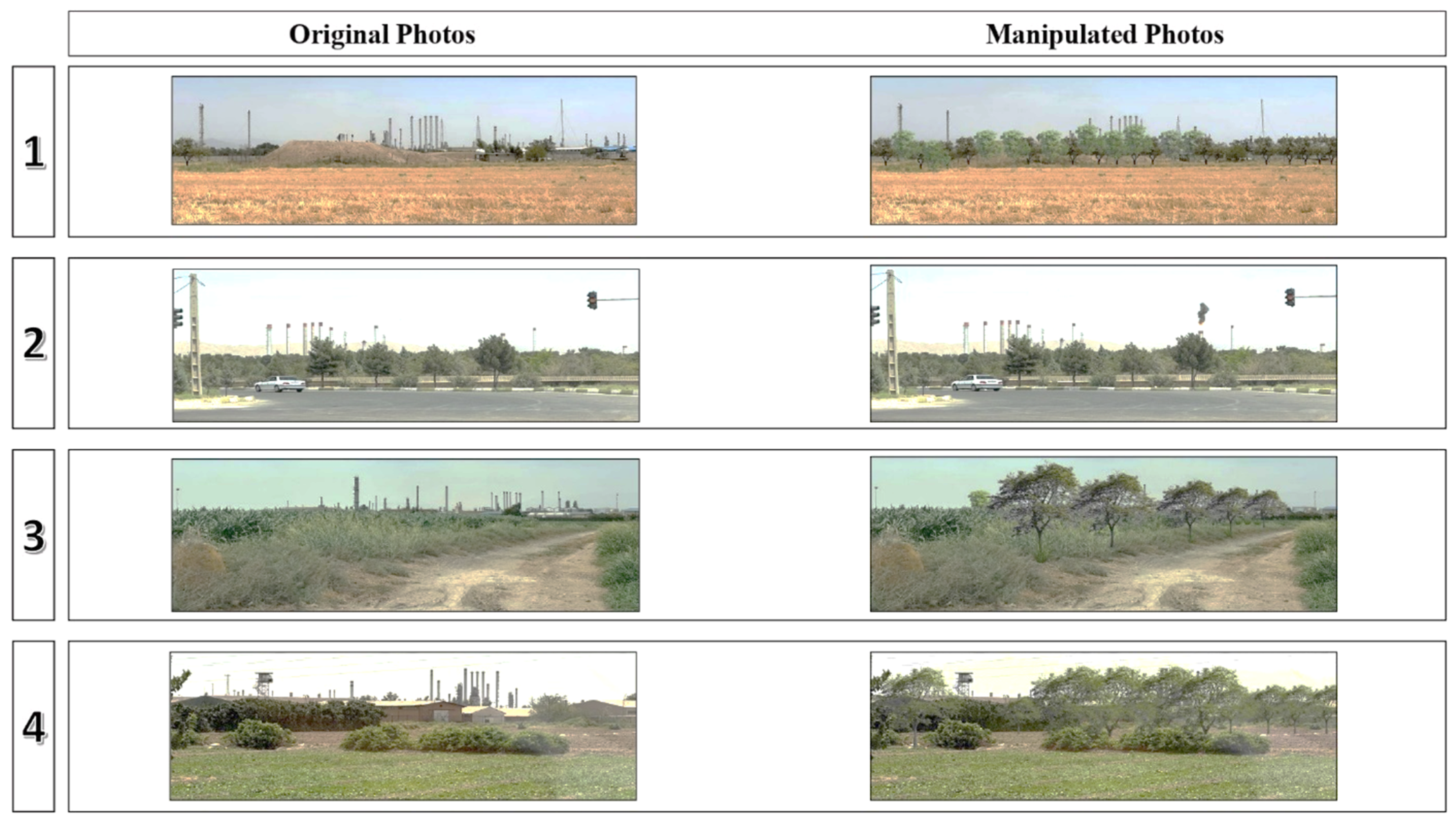

Original Photographs versus Manipulated Photographs

Relationship Between Stress Level and Landscape Values Perception

4. Discussion

General Observations

Implications For Planning

Consideration of The Applied Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. Matar and L. F. Hatch, Chemistry of petrochemical processes, 2nd ed. Boston: Gulf Professional Pub, 2001.

- World Health Organization, “Environment and Health Risks: A Review of the Influence and Effects of Social Inequalities.,” WHO Reg. Off. Eur., 2010.

- T.-H. Yuan, Y.-C. Shen, R.-H. Shie, S.-H. Hung, C.-F. Chen, and C.-C. Chan, “Increased cancers among residents living in the neighborhood of a petrochemical complex: A 12-year retrospective cohort study,” Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health, vol. 221, no. 2, pp. 308–314, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C.-K. Lin, H.-Y. Hung, D. C. Christiani, F. Forastiere, and R.-T. Lin, “Lung cancer mortality of residents living near petrochemical industrial complexes: a meta-analysis,” Environ. Health, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 101, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C.-K. Lin, Y.-T. Hsu, D. C. Christiani, H.-Y. Hung, and R.-T. Lin, “Risks and burden of lung cancer incidence for residential petrochemical industrial complexes: a meta-analysis and application,” Environ. Int., vol. 121, pp. 404–414, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C.-K. Lin, Y.-T. Hsu, K. D. Brown, B. Pokharel, Y. Wei, and S.-T. Chen, “Residential exposure to petrochemical industrial complexes and the risk of leukemia: A systematic review and exposure-response meta-analysis,” Environ. Pollut., vol. 258, p. 113476, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C.-H. S. Chen, T.-H. Yuan, R.-H. Shie, K.-Y. Wu, and C.-C. Chan, “Linking sources to early effects by profiling urine metabolome of residents living near oil refineries and coal-fired power plants,” Environ. Int., vol. 102, pp. 87–96, 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Vicens, L. Heredia, E. Bustamante, Y. Pérez, J. L. Domingo, and M. Torrente, “Does living close to a petrochemical complex increase the adverse psychological effects of the COVID-19 lockdown?,” Plos One, vol. 16, no. 3, p. e0249058, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Calderón-Garcidueñas, R. Torres-Jardón, R. J. Kulesza, S.-B. Park, and A. D’Angiulli, “Air pollution and detrimental effects on children’s brain. The need for a multidisciplinary approach to the issue complexity and challenges,” Front. Hum. Neurosci., vol. 8, p. 613, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Block et al., “The outdoor air pollution and brain health workshop,” Neurotoxicology, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 972–984, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Gayman, R. L. Brown, and M. Cui, “Depressive symptoms and bodily pain: the role of physical disability and social stress,” Stress Health, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 52–63, Feb. 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Peters and B. S. McEwen, “Stress habituation, body shape and cardiovascular mortality,” Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., vol. 56, pp. 139–150, 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. Olson and M. A. Surrette, “The interrelationship among stress, anxiety, and depression in law enforcement personnel,” J. Police Crim. Psychol., vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 36–44, 2004. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Bardeen, T. A. Fergus, and H. K. Orcutt, “Experiential avoidance as a moderator of the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and perceived stress,” Behav. Ther., vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 459–469, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Pu, and H. Hou, “Effect of perceived stress on depression of Chinese ‘Ant Tribe’ and the moderating role of dispositional optimism,” J. Health Psychol., vol. 21, no. 11, pp. 2725–2731, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. Grahn and U. A. Stigsdotter, “Landscape planning and stress,” Urban For. Urban Green., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1–18, Jan. 2003. [CrossRef]

- J. Appleby, “Spending on health and social care over the next 50 years. Why think long term ?,” presented at the Spending on health and social care over the next 50 years. Why think long term ?, 2013. Accessed: Apr. 04, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=26923988.

- W. Thompson, “Urban open space in the 21st century,” Landsc. Urban Plan., vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 59–72, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Evered, “The role of the urban landscape in restoring mental health in Sheffield, UK: service user perspectives,” Landsc. Res., vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 678–694, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Skärbäck, “COMMENTARY: Landscape Planning to Promote Well Being: Studies and Examples from Sweden,” Environ. Pract., vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 206–217, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- C. Ward Thompson, J. Roe, P. Aspinall, R. Mitchell, A. Clow, and D. Miller, “More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns,” Landsc. Urban Plan., vol. 105, no. 3, pp. 221–229, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. E. van den Berg, J. Maas, R. A. Verheij, and P. P. Groenewegen, “Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health,” Soc. Sci. Med., vol. 70, no. 8, pp. 1203–1210, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- U. K. Stigsdotter, O. Ekholm, J. Schipperijn, M. Toftager, F. Kamper-Jørgensen, and T. B. Randrup, “Health promoting outdoor environments - Associations between green space, and health, health-related quality of life and stress based on a Danish national representative survey,” Scand. J. Public Health, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 411–417, Jun. 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. Grahn and U. K. Stigsdotter, “The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration,” Landsc. Urban Plan., vol. 94, no. 3, pp. 264–275, Mar. 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. Lottrup, P. Grahn, and U. K. Stigsdotter, “Workplace greenery and perceived level of stress: Benefits of access to a green outdoor environment at the workplace,” Landsc. Urban Plan., vol. 110, pp. 5–11, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Vujcic, J. Tomicevic-Dubljevic, I. Zivojinovic, and O. Toskovic, “Connection between urban green areas and visitors’ physical and mental well-being,” Urban For. Urban Green., vol. 40, pp. 299–307, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shu, C. Wu, and Y. Zhai, “Impacts of Landscape Type, Viewing Distance, and Permeability on Anxiety, Depression, and Stress,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, vol. 19, no. 16, Art. no. 16, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Ha, H. J. Kim, and K. A. With, “Urban green space alone is not enough: A landscape analysis linking the spatial distribution of urban green space to mental health in the city of Chicago,” Landsc. Urban Plan., vol. 218, p. 104309, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Korpilo, E. Nyberg, K. Vierikko, H. Nieminen, G. Arciniegas, and C. M. Raymond, “Developing a Multi-sensory Public Participation GIS (MSPPGIS) method for integrating landscape values and soundscapes of urban green infrastructure,” Landsc. Urban Plan., vol. 230, p. 104617, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Schüpbach and S. Kay, “Validation of a visual landscape quality indicator for agrarian landscapes using public participatory GIS data,” Landsc. Urban Plan., vol. 241, p. 104906, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Valánszki, L. S. Kristensen, S. Jombach, M. Ladányi, K. Filepné Kovács, and A. Fekete, “Assessing Relations between Cultural Ecosystem Services, Physical Landscape Features and Accessibility in Central-Eastern Europe: A PPGIS Empirical Study from Hungary,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Stahl Olafsson et al., “Comparing landscape value patterns between participatory mapping and geolocated social media content across Europe,” Landsc. Urban Plan., vol. 226, p. 104511, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Garcia, M. Benages-Albert, D. Pavón, A. Ribas, J. Garcia-Aymerich, and P. Vall-Casas, “Public participation GIS for assessing landscape values and improvement preferences in urban stream corridors,” Appl. Geogr., vol. 87, pp. 184–196, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Pykett et al., “Developing a Citizen Social Science approach to understand urban stress and promote wellbeing in urban communities,” Palgrave Commun., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–11, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, A. Ojala, K. Korpela, T. Lanki, Y. Tsunetsugu, and T. Kagawa, “The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment,” J. Environ. Psychol., vol. 38, pp. 1–9, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- OICO, “Tehran Oil Refinery,” Oil Industries’ Commissioning And Operation Company. Accessed: Dec. 11, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.oico.ir/en/Projects/tehran-oil-refinery.

- S. Cohen, T. Kamarck, and R. Mermelstein, “A global measure of perceived stress,” J. Health Soc. Behav., pp. 385–396, 1983. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Warttig, M. J. Forshaw, J. South, and A. K. White, “New, normative, English-sample data for the Short Form Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4),” J. Health Psychol., vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 1617–1628, Dec. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Svobodova, P. Sklenicka, K. Molnarova, and J. Vojar, “Does the composition of landscape photographs affect visual preferences? The rule of the Golden Section and the position of the horizon,” J. Environ. Psychol., vol. 38, pp. 143–152, 2014. [CrossRef]

- “Cambridge Free English Dictionary and Thesaurus.” Accessed: Feb. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/.

| Adjectives | description |

| Anxious | feeling or showing worry, nervousness, or unease about something with an uncertain outcome. |

| Serene | peaceful and calm; worried by nothing. |

| Restless | unwilling or unable to stay still or to be quiet and calm, because you are worried or bored. |

| Tranquil | calm and peaceful and without noise, violence and worry. |

| Tense | nervous and worried and unable to relax. |

| Calm | peaceful, quiet, and without worry. |

| Age group | Female | Male | N/A | Total |

| N/A | 8.18% | 9.09% | 1.36% | 18.64% |

| 16–24 years | 14.55% | 7.73% | 0.45% | 22.73% |

| 25–34 years | 16.82% | 14.55% | 0.00% | 31.36% |

| 35–44 years | 7.27% | 10.00% | 0.00% | 17.27% |

| 45–54 years | 2.73% | 1.82% | 0.45% | 5.00% |

| More than 55 years | 2.73% | 2.27% | 0.00% | 5.00% |

| Total | 52.27% | 45.45% | 2.27% | 100.00% |

| Score | PSS-1 | PSS-4 | Score | PSS-2 | PSS-3 |

| Never (0) | 16.82% | 20.45% | Never (4) | 14.09% | 10.00% |

| Almost Never (1) | 20.00% | 20.91% | Almost Never (3) | 31.36% | 43.18% |

| Sometimes (2) | 8.64% | 10.00% | Sometimes (2) | 6.36% | 4.09% |

| Fairly Often (3) | 50.91% | 44.55% | Fairly Often (1) | 45.00% | 34.55% |

| Very Often (4) | 3.64% | 4.09% | Very Often (0) | 3.18% | 8.18% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | Total | 100% | 100% |

| Photographs/Adjectives | Anxious/Serene | Restless/Tranquil | Tense/Calm | |

| Photograph 1 | Original | Anxious (50.45%) | Restless (35.35%) | Tense (52.73%) |

| Manipulated | Anxious (39.09%) | Tranquil (37.73%) | Tense (43.18%) | |

| Photograph 2 | Original | Anxious (48.40%) | Restless (45%) | Tense (48.64%) |

| Manipulated | Anxious (49.55%) | Restless (49.55%) | Tense (50%) | |

| Photograph 3 | Original | Anxious (53.18%) | Restless (31.82%) | Tense (51.82%) |

| Manipulated | Serene (45.45%) | Tranquil (56.36%) | Calm (34.55%) | |

| Photograph 4 | Original | Anxious (46.82%) | Restless (40.91%) | Tense (45.91%) |

| Manipulated | Anxious (35%) | Tranquil (44.55%) | Tense (38.64%) | |

| Model Fit Measures | ||||||

| Overall Model Test | ||||||

| Deviance | AIC | BIC | R²McF | χ² | df | p |

| 229 | 523 | 1022 | 0.442 | 182 | 144 | 0.019 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||||||||||

| Level of stress | Predictor | Estimate | Lower | Upper | SE | Z | p | ||||||||

| High - Low | Intercept | 4.6995 | -2.3343 | 11.7332 | 3.58873 | 1.3095 | 0.190 | ||||||||

| Photograph 1-(Anxious/Serene): | |||||||||||||||

| Anxious – Neutral | 2.1149 | -1.1772 | 5.4069 | 1.67964 | 1.2591 | 0.208 | |||||||||

| Serene – Neutral | 1.1958 | -2.7228 | 5.1143 | 1.99931 | 0.5981 | 0.550 | |||||||||

| Very Serene – Neutral | -14.2037 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | |||||||||

| Very anxious – Neutral | 20.1354 | -64.4262 | 104.6971 | 43.14450 | 0.4667 | 0.641 | |||||||||

| Photograph 2-(Anxious/Serene): | |||||||||||||||

| Anxious – Neutral | -5.4329 | -10.2025 | -0.6633 | 2.43353 | -2.2325 | 0.026 | |||||||||

| Serene – Neutral | -9.2535 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | |||||||||

| Very Serene – Neutral | -12.8545 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | |||||||||

| Very anxious – Neutral | -3.1994 | -10.8985 | 4.4997 | 3.92820 | -0.8145 | 0.415 | |||||||||

| Photograph 3-(Anxious/Serene): | |||||||||||||||

| Anxious – Neutral | 4.7599 | -1.1784 | 10.6982 | 3.02981 | 1.5710 | 0.116 | |||||||||

| Serene – Neutral | -1.6589 | -6.9051 | 3.5873 | 2.67667 | -0.6198 | 0.535 | |||||||||

| Very Serene – Neutral | 1.3853 | -4.6191 | 7.3898 | 3.06355 | 0.4522 | 0.651 | |||||||||

| Very anxious – Neutral | 17.4496 | -51.6138 | 86.5130 | 35.23706 | 0.4952 | 0.620 | |||||||||

| Photograph 4-(Anxious/Serene): | |||||||||||||||

| Anxious – Neutral | -1.1640 | -5.7256 | 3.3976 | 2.32740 | -0.5001 | 0.617 | |||||||||

| Serene – Neutral | -1.4336 | -5.2306 | 2.3634 | 1.93727 | -0.7400 | 0.459 | |||||||||

| Very Serene – Neutral | 7.5441 | -1.6046 | 16.6927 | 4.66778 | 1.6162 | 0.106 | |||||||||

| Very anxious – Neutral | -7.3304 | -15.1242 | 0.4633 | 3.97649 | -1.8434 | 0.065 | |||||||||

| Photograph 1-(Restless/Tranquil): | |||||||||||||||

| Restless – Neutral | -1.3410 | -5.1444 | 2.4624 | 1.94055 | -0.6910 | 0.490 | |||||||||

| Tranquil – Neutral | -0.0192 | -3.1819 | 3.1435 | 1.61366 | -0.0119 | 0.990 | |||||||||

| Very Tranquil – Neutral | 22.6392 | 21.7142 | 23.5642 | 0.47196 | 47.9685 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Very restless – Neutral | 14.9166 | -144.8612 | 174.6945 | 81.52081 | 0.1830 | 0.855 | |||||||||

| Photograph 2-(Restless/Tranquil): | |||||||||||||||

| Restless – Neutral | 4.1601 | -0.2208 | 8.5410 | 2.23518 | 1.8612 | 0.063 | |||||||||

| Tranquil – Neutral | -0.2035 | -4.6895 | 4.2826 | 2.28885 | -0.0889 | 0.929 | |||||||||

| Very Tranquil – Neutral | 9.3087 | -154.5762 | 173.1935 | 83.61627 | 0.1113 | 0.911 | |||||||||

| Very restless – Neutral | 1.2321 | -5.8739 | 8.3381 | 3.62559 | 0.3398 | 0.734 | |||||||||

| Photograph 3-(Restless/Tranquil): | |||||||||||||||

| Restless – Neutral | 19.2499 | -63.6016 | 102.1015 | 42.27198 | 0.4554 | 0.649 | |||||||||

| Tranquil – Neutral | 1.6671 | -2.9020 | 6.2362 | 2.33122 | 0.7151 | 0.475 | |||||||||

| Very Tranquil – Neutral | -0.9003 | -5.7378 | 3.9372 | 2.46815 | -0.3648 | 0.715 | |||||||||

| Very restless – Neutral | -4.2033 | -39.3953 | 30.9888 | 17.95547 | -0.2341 | 0.815 | |||||||||

| Photograph 4-(Restless/Tranquil): | |||||||||||||||

| Restless – Neutral | 0.8658 | -4.1287 | 5.8604 | 2.54828 | 0.3398 | 0.734 | |||||||||

| Tranquil – Neutral | 0.4577 | -2.5142 | 3.4295 | 1.51628 | 0.3018 | 0.763 | |||||||||

| Very Tranquil – Neutral | -6.8524 | -14.2658 | 0.5610 | 3.78241 | -1.8116 | 0.070 | |||||||||

| Very restless – Neutral | 18.1303 | -103.2041 | 139.4647 | 61.90645 | 0.2929 | 0.770 | |||||||||

| Photograph 1-(Tense/Calm): | |||||||||||||||

| Calm – Neutral | -2.0745 | -6.5029 | 2.3539 | 2.25942 | -0.9182 | 0.359 | |||||||||

| Tense – Neutral | -3.7870 | -8.0405 | 0.4665 | 2.17020 | -1.7450 | 0.081 | |||||||||

| Very calm – Neutral | -2.4014 | -8.3044 | 3.5017 | 3.01182 | -0.7973 | 0.425 | |||||||||

| Very tense – Neutral | -20.8973 | -103.2092 | 61.4145 | 41.99662 | -0.4976 | 0.619 | |||||||||

| Photograph 2-(Tense/Calm): | |||||||||||||||

| Calm – Neutral | -5.5131 | -11.9175 | 0.8912 | 3.26759 | -1.6872 | 0.092 | |||||||||

| Tense – Neutral | -1.2143 | -7.0962 | 4.6677 | 3.00107 | -0.4046 | 0.686 | |||||||||

| Very calm – Neutral | -31.1297 | -31.1297 | -31.1297 | 3.23e-8 | -9.63e−8 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Very tense – Neutral | -3.2254 | -10.7030 | 4.2523 | 3.81521 | -0.8454 | 0.398 | |||||||||

| Photograph 3-(Tense/Calm): | |||||||||||||||

| Calm – Neutral | 2.8066 | -0.9492 | 6.5625 | 1.91628 | 1.4646 | 0.143 | |||||||||

| Tense – Neutral | -0.7021 | -5.7671 | 4.3629 | 2.58423 | -0.2717 | 0.786 | |||||||||

| Very calm – Neutral | -1.3507 | -5.5685 | 2.8671 | 2.15198 | -0.6276 | 0.530 | |||||||||

| Very tense – Neutral | -8.4144 | -17.9133 | 1.0844 | 4.84643 | -1.7362 | 0.083 | |||||||||

| Photograph 4-(Tense/Calm): | |||||||||||||||

| Calm – Neutral | -0.4287 | -4.4682 | 3.6108 | 2.06102 | -0.2080 | 0.835 | |||||||||

| Tense – Neutral | 6.0316 | -0.2591 | 12.3223 | 3.20960 | 1.8792 | 0.060 | |||||||||

| Very calm – Neutral | 3.2780 | -2.2398 | 8.7959 | 2.81528 | 1.1644 | 0.244 | |||||||||

| Very tense – Neutral | 21.5797 | -44.7373 | 87.8967 | 33.83583 | 0.6378 | 0.524 | |||||||||

| Medium - Low | Intercept | 5.2528 | -1.6813 | 12.1870 | 3.53791 | 1.4847 | 0.138 | ||||||||

| Photograph 1-(Anxious/Serene): | |||||||||||||||

| Anxious – Neutral | 1.8543 | -1.3422 | 5.0507 | 1.63086 | 1.1370 | 0.256 | |||||||||

| Serene – Neutral | 1.4828 | -2.2499 | 5.2155 | 1.90446 | 0.7786 | 0.436 | |||||||||

| Very Serene – Neutral | 17.9843 | 17.9840 | 17.9846 | 1.46e-4 | 122913.8936 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Very anxious – Neutral | 19.0630 | -65.4704 | 103.5965 | 43.13012 | 0.4420 | 0.658 | |||||||||

| Photograph 2-(Anxious/Serene): | |||||||||||||||

| Anxious – Neutral | -4.8493 | -9.5388 | -0.1597 | 2.39267 | -2.0267 | 0.043 | |||||||||

| Serene – Neutral | 16.2681 | 16.2661 | 16.2702 | 0.00105 | 15466.8847 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Very Serene – Neutral | -30.4460 | -30.4460 | -30.4460 | 1.12e-5 | -2.71e−6 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Very anxious – Neutral | -2.5419 | -10.1186 | 5.0348 | 3.86572 | -0.6576 | 0.511 | |||||||||

| Photograph 3-(Anxious/Serene): | |||||||||||||||

| Anxious – Neutral | 4.6028 | -1.2304 | 10.4359 | 2.97617 | 1.5465 | 0.122 | |||||||||

| Serene – Neutral | -1.1342 | -6.2639 | 3.9956 | 2.61725 | -0.4333 | 0.665 | |||||||||

| Very Serene – Neutral | 2.9104 | -2.8587 | 8.6795 | 2.94347 | 0.9888 | 0.323 | |||||||||

| Very anxious – Neutral | 19.3867 | -49.6427 | 88.4161 | 35.21974 | 0.5505 | 0.582 | |||||||||

| Photograph 4-(Anxious/Serene): | |||||||||||||||

| Anxious – Neutral | -0.8112 | -5.2726 | 3.6502 | 2.27625 | -0.3564 | 0.722 | |||||||||

| Serene – Neutral | -0.9796 | -4.5997 | 2.6405 | 1.84703 | -0.5304 | 0.596 | |||||||||

| Very Serene – Neutral | 5.4433 | -3.5797 | 14.4663 | 4.60367 | 1.1824 | 0.237 | |||||||||

| Very anxious – Neutral | -8.7050 | -16.4425 | -0.9675 | 3.94777 | -2.2050 | 0.027 | |||||||||

| Photograph 1-(Restless/Tranquil): | |||||||||||||||

| Restless – Neutral | -0.9996 | -4.6794 | 2.6803 | 1.87753 | -0.5324 | 0.594 | |||||||||

| Tranquil – Neutral | 0.6944 | -2.3422 | 3.7310 | 1.54932 | 0.4482 | 0.654 | |||||||||

| Very Tranquil – Neutral | 22.2857 | 21.3607 | 23.2107 | 0.47196 | 47.2191 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Very restless – Neutral | 14.1970 | -145.5799 | 173.9739 | 81.52033 | 0.1742 | 0.862 | |||||||||

| Photograph 2-(Restless/Tranquil): | |||||||||||||||

| Restless – Neutral | 4.1021 | -0.1943 | 8.3984 | 2.19206 | 1.8713 | 0.061 | |||||||||

| Tranquil – Neutral | 0.6743 | -3.6219 | 4.9706 | 2.19199 | 0.3076 | 0.758 | |||||||||

| Very Tranquil – Neutral | 7.8182 | -156.1162 | 171.7526 | 83.64155 | 0.0935 | 0.926 | |||||||||

| Very restless – Neutral | 2.2883 | -4.6603 | 9.2369 | 3.54527 | 0.6455 | 0.519 | |||||||||

| Photograph 3-(Restless/Tranquil): | |||||||||||||||

| Restless – Neutral | 19.7659 | -63.0708 | 102.6026 | 42.26439 | 0.4677 | 0.640 | |||||||||

| Tranquil – Neutral | 1.4255 | -3.0346 | 5.8856 | 2.27562 | 0.6264 | 0.531 | |||||||||

| Very Tranquil – Neutral | -1.0140 | -5.6939 | 3.6660 | 2.38779 | -0.4246 | 0.671 | |||||||||

| Very restless – Neutral | -4.4225 | -39.5804 | 30.7354 | 17.93805 | -0.2465 | 0.805 | |||||||||

| Photograph 4-(Restless/Tranquil): | |||||||||||||||

| Restless – Neutral | 0.7631 | -4.1926 | 5.7187 | 2.52844 | 0.3018 | 0.763 | |||||||||

| Tranquil – Neutral | 0.3786 | -2.4111 | 3.1684 | 1.42336 | 0.2660 | 0.790 | |||||||||

| Very Tranquil – Neutral | -7.9392 | -15.3128 | -0.5656 | 3.76212 | -2.1103 | 0.035 | |||||||||

| Very restless – Neutral | 17.6491 | -103.6811 | 138.9792 | 61.90429 | 0.2851 | 0.776 | |||||||||

| Photograph 1-(Tense/Calm): | |||||||||||||||

| Calm – Neutral | -1.4782 | -5.8054 | 2.8490 | 2.20780 | -0.6696 | 0.503 | |||||||||

| Tense – Neutral | -3.1430 | -7.3019 | 1.0160 | 2.12195 | -1.4812 | 0.139 | |||||||||

| Very calm – Neutral | -4.9258 | -10.8244 | 0.9729 | 3.00959 | -1.6367 | 0.102 | |||||||||

| Very tense – Neutral | -21.6336 | -103.9102 | 60.6430 | 41.97862 | -0.5153 | 0.606 | |||||||||

| Photograph 2-(Tense/Calm): | |||||||||||||||

| Calm – Neutral | -6.1634 | -12.4447 | 0.1179 | 3.20481 | -1.9232 | 0.054 | |||||||||

| Tense – Neutral | -1.8393 | -7.6322 | 3.9536 | 2.95560 | -0.6223 | 0.534 | |||||||||

| Very calm – Neutral | -5.5442 | -13.6020 | 2.5135 | 4.11117 | -1.3486 | 0.177 | |||||||||

| Very tense – Neutral | -3.5975 | -10.9240 | 3.7290 | 3.73809 | -0.9624 | 0.336 | |||||||||

| Photograph 3-(Tense/Calm): | |||||||||||||||

| Calm – Neutral | 2.3387 | -1.3210 | 5.9984 | 1.86723 | 1.2525 | 0.210 | |||||||||

| Tense – Neutral | -1.1078 | -6.0398 | 3.8243 | 2.51638 | -0.4402 | 0.660 | |||||||||

| Very calm – Neutral | -1.4103 | -5.4198 | 2.5992 | 2.04568 | -0.6894 | 0.491 | |||||||||

| Very tense – Neutral | -9.2410 | -18.5987 | 0.1167 | 4.77443 | -1.9355 | 0.053 | |||||||||

| Photograph 4-(Tense/Calm): | |||||||||||||||

| Calm – Neutral | 0.3186 | -3.5597 | 4.1969 | 1.97874 | 0.1610 | 0.872 | |||||||||

| Tense – Neutral | 5.7890 | -0.3843 | 11.9624 | 3.14972 | 1.8380 | 0.066 | |||||||||

| Very calm – Neutral | 3.8337 | -1.5243 | 9.1917 | 2.73372 | 1.4024 | 0.161 | |||||||||

| Very tense – Neutral | 23.1036 | -43.2034 | 89.4106 | 33.83072 | 0.6829 | 0.495 | |||||||||

| Very High - Low | Intercept | -26.5160 | -316.5767 | 263.5446 | 147.99285 | -0.1792 | 0.858 | ||||||||

| Photograph 1-(Anxious/Serene): | |||||||||||||||

| Anxious – Neutral | 10.7056 | -333.2569 | 354.6681 | 175.49428 | 0.0610 | 0.951 | |||||||||

| Serene – Neutral | -3.7956 | -289.8616 | 282.2704 | 145.95471 | -0.0260 | 0.979 | |||||||||

| Very Serene – Neutral | -1.4589 | -1.4592 | -1.4586 | 1.47e-4 | -9919.0120 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Very anxious – Neutral | 21.7959 | -126.4369 | 170.0287 | 75.63037 | 0.2882 | 0.773 | |||||||||

| Photograph 2-(Anxious/Serene): | |||||||||||||||

| Anxious – Neutral | -5.9914 | -276.2947 | 264.3119 | 137.91239 | -0.0434 | 0.965 | |||||||||

| Serene – Neutral | -0.8896 | -0.8914 | -0.8878 | 9.18e-4 | -969.4100 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Very Serene – Neutral | -6.3288 | -7.3901 | -5.2675 | 0.54150 | -11.6876 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Very anxious – Neutral | 1.8782 | -255.6415 | 259.3979 | 131.39000 | 0.0143 | 0.989 | |||||||||

| Photograph 3-(Anxious/Serene): | |||||||||||||||

| Anxious – Neutral | -5.5638 | -201.5949 | 190.4674 | 100.01772 | -0.0556 | 0.956 | |||||||||

| Serene – Neutral | 4.9162 | -265.2728 | 275.1053 | 137.85407 | 0.0357 | 0.972 | |||||||||

| Very Serene – Neutral | -17.9057 | -232.8648 | 197.0534 | 109.67504 | -0.1633 | 0.870 | |||||||||

| Very anxious – Neutral | 24.9166 | -125.9910 | 175.8242 | 76.99510 | 0.3236 | 0.746 | |||||||||

| Photograph 4-(Anxious/Serene): | |||||||||||||||

| Anxious – Neutral | -18.0372 | -323.5809 | 287.5064 | 155.89249 | -0.1157 | 0.908 | |||||||||

| Serene – Neutral | -27.5125 | -339.6767 | 284.6517 | 159.27037 | -0.1727 | 0.863 | |||||||||

| Very Serene – Neutral | 22.8097 | -223.9838 | 269.6032 | 125.91736 | 0.1811 | 0.856 | |||||||||

| Very anxious – Neutral | -23.1986 | -244.3849 | 197.9876 | 112.85220 | -0.2056 | 0.837 | |||||||||

| Photograph 1-(Restless/Tranquil): | |||||||||||||||

| Restless – Neutral | 9.9340 | -250.1160 | 269.9840 | 132.68102 | 0.0749 | 0.940 | |||||||||

| Tranquil – Neutral | 5.6066 | -167.0692 | 178.2825 | 88.10154 | 0.0636 | 0.949 | |||||||||

| Very Tranquil – Neutral | 8.2108 | 8.2106 | 8.2110 | 8.99e-5 | 91318.9991 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Very restless – Neutral | -6.6587 | -326.1989 | 312.8814 | 163.03368 | -0.0408 | 0.967 | |||||||||

| Photograph 2-(Restless/Tranquil): | |||||||||||||||

| Restless – Neutral | 16.2813 | -294.4418 | 327.0044 | 158.53511 | 0.1027 | 0.918 | |||||||||

| Tranquil – Neutral | 23.7384 | -264.3237 | 311.8006 | 146.97317 | 0.1615 | 0.872 | |||||||||

| Very Tranquil – Neutral | -0.0321 | -0.0323 | -0.0320 | 8.55e-5 | -375.8820 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Very restless – Neutral | 19.9280 | -261.9520 | 301.8079 | 143.81895 | 0.1386 | 0.890 | |||||||||

| Photograph 3-(Restless/Tranquil): | |||||||||||||||

| Restless – Neutral | 30.3006 | -368.9689 | 429.5702 | 203.71271 | 0.1487 | 0.882 | |||||||||

| Tranquil – Neutral | 1.1550 | -223.9985 | 226.3085 | 114.87635 | 0.0101 | 0.992 | |||||||||

| Very Tranquil – Neutral | -14.8075 | -183.8176 | 154.2026 | 86.23123 | -0.1717 | 0.864 | |||||||||

| Very restless – Neutral | -3.4429 | -35.0953 | 28.2096 | 16.14952 | -0.2132 | 0.831 | |||||||||

| Photograph 4-(Restless/Tranquil): | |||||||||||||||

| Restless – Neutral | -1.7501 | -262.6201 | 259.1198 | 133.09936 | -0.0131 | 0.990 | |||||||||

| Tranquil – Neutral | 2.7264 | -262.4988 | 267.9516 | 135.32146 | 0.0201 | 0.984 | |||||||||

| Very Tranquil – Neutral | -8.1195 | -20.1809 | 3.9419 | 6.15387 | -1.3194 | 0.187 | |||||||||

| Very restless – Neutral | -4.7047 | -247.2398 | 237.8303 | 123.74465 | -0.0380 | 0.970 | |||||||||

| Photograph 1-(Tense/Calm): | |||||||||||||||

| Calm – Neutral | 4.9525 | -303.9748 | 313.8799 | 157.61889 | 0.0314 | 0.975 | |||||||||

| Tense – Neutral | -22.6183 | -238.5635 | 193.3270 | 110.17817 | -0.2053 | 0.837 | |||||||||

| Very calm – Neutral | -3.2255 | -172.1436 | 165.6925 | 86.18427 | -0.0374 | 0.970 | |||||||||

| Very tense – Neutral | -28.5373 | -453.9261 | 396.8516 | 217.03912 | -0.1315 | 0.895 | |||||||||

| Photograph 2-(Tense/Calm): | |||||||||||||||

| Calm – Neutral | -26.2947 | -491.2659 | 438.6765 | 237.23456 | -0.1108 | 0.912 | |||||||||

| Tense – Neutral | -7.7818 | -234.8986 | 219.3349 | 115.87803 | -0.0672 | 0.946 | |||||||||

| Very calm – Neutral | 23.3459 | -185.6352 | 232.3270 | 106.62496 | 0.2190 | 0.827 | |||||||||

| Very tense – Neutral | -13.7971 | -227.3986 | 199.8043 | 108.98232 | -0.1266 | 0.899 | |||||||||

| Photograph 3-(Tense/Calm): | |||||||||||||||

| Calm – Neutral | 17.7439 | -141.8107 | 177.2985 | 81.40692 | 0.2180 | 0.827 | |||||||||

| Tense – Neutral | 4.3553 | -215.6174 | 224.3280 | 112.23303 | 0.0388 | 0.969 | |||||||||

| Very calm – Neutral | 15.8358 | -249.5955 | 281.2671 | 135.42661 | 0.1169 | 0.907 | |||||||||

| Very tense – Neutral | 15.7802 | -174.8174 | 206.3777 | 97.24542 | 0.1623 | 0.871 | |||||||||

| Photograph 4-(Tense/Calm): | |||||||||||||||

| Calm – Neutral | -4.8382 | -264.2047 | 254.5283 | 132.33226 | -0.0366 | 0.971 | |||||||||

| Tense – Neutral | -2.0770 | -148.2941 | 144.1401 | 74.60193 | -0.0278 | 0.978 | |||||||||

| Very calm – Neutral | -25.5973 | -143.0798 | 91.8852 | 59.94116 | -0.4270 | 0.669 | |||||||||

| Very tense – Neutral | 47.0470 | -73.6793 | 167.7733 | 61.59619 | 0.7638 | 0.445 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).