1. Introduction

Climate changes are leading farmers to rethink specialized farming systems mainly in most vulnerable areas like the Mediterranean. The main forecasting scenarios for this area show summer rainfall decreasing by 10 to 30% and more frequent extreme events (heat waves, droughts, floods and fires) (Pouffary et al., 2019; MedECC, 2020). Decrease on water availability is already considered an issue by decision makers in this area (OECD, 2012; Fader et al., 2020), and it could be worsened considering the expected demographic growth and increase on agricultural needs (Fraga et al., 2018; Funes et al., 2021). The advancement of plants phenological phases (Gordo and Sanz, 2010; Ivits et al 2012) have caused increasing spring frost risk after bud burst, mainly on perennial crops (Lereboullet et al., 2013) and it becomes an important concern for farmers in those regions (Legave at al., 2013; Lereboullet et al., 2013). Furthermore, volatile global markets can still become more uncertain in the future, thanks to climate change affecting farms and households economic (Gurgel et al., 2021). Building up the capacity of farms to adapt face impacts of climate change is an important challenge for the agricultural sector and become a key research topic (Marshall et al., 2014; Vanschoenwinkel et al., 2019; Vernooy et al., 2022). Different solutions can be adopted by farmers to adapt their productions to climate change. In particular, the possible solutions can go from the incremental ones, such us the improvement of the irrigation systems (Fader et al. 2016) or the adoption of more resistant varieties (Tack et al., 2015), until the most transformative ones, such as the implementation of mixed agroecological practices (Morugán-Coronado et al., 2020; Ioannidou et al., 2022) or the change on the type of production (Karimi et al., 2020).

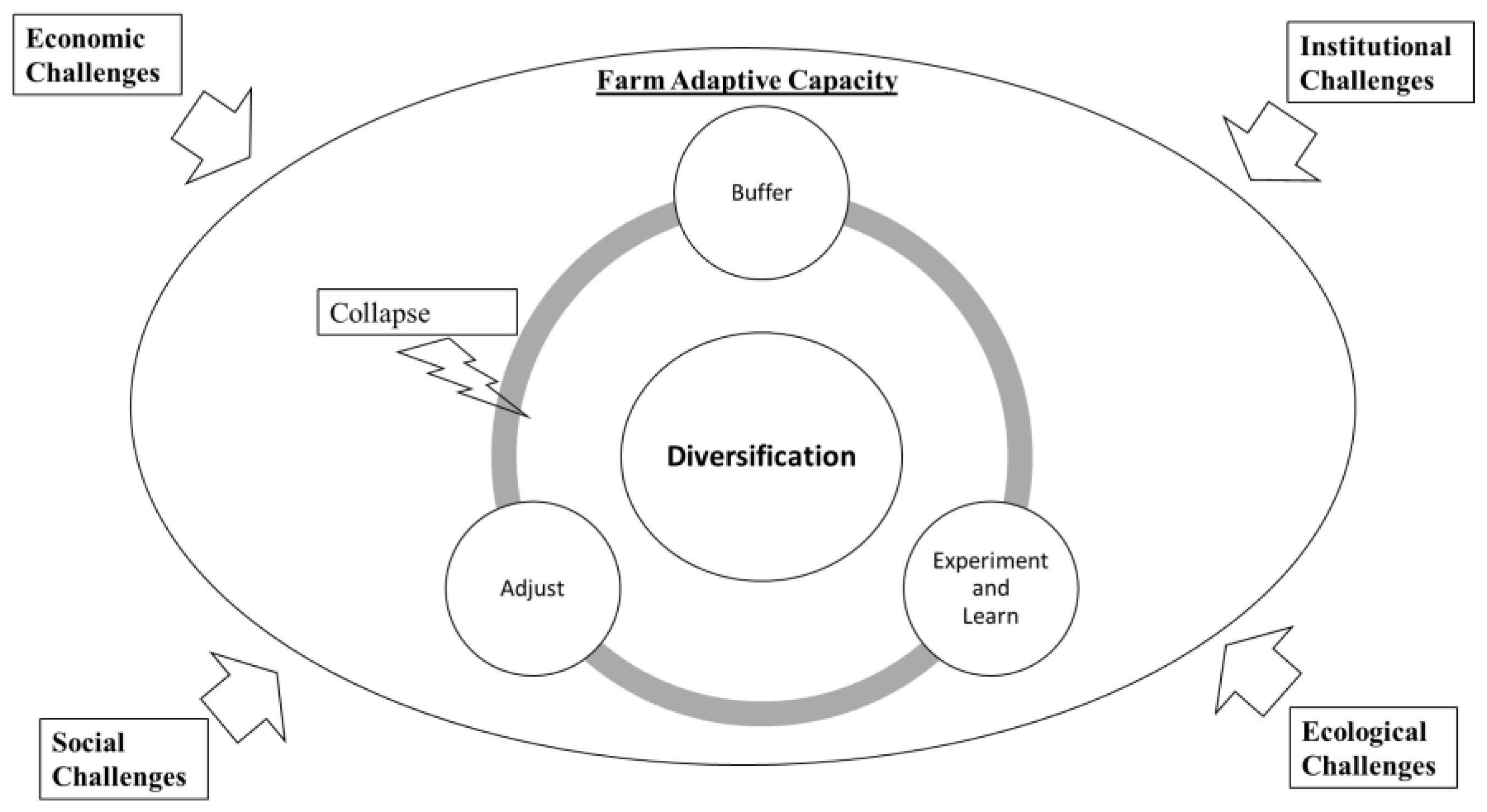

The capacity of farmer to adapt is one of the main components of the farms’ resilience (Darnhofer, 2014; 2021; Meuwissen et al., 2019; Slijper et al., 2022). Farms resilience is defined as the ability of farming systems to cope with disturbances (Darnhofer, 2014; Meuwissen et al., 2019). According to Darnhofer (2014), farms resilience covers three main aspects: buffer capability, adaptive capability and transformative capability. The buffer capability represents the robustness of the system and refers to the processes allowing farms to anticipate, absorb and resist to shocks (Darnhofer et al., 2010; Meuwissen et al., 2019). The adaptive capability is the ability of a system to adjust face of changing external drivers and internal preferences while do not completely change the faming systems (Darnhofer 2014; Meuwissen et al., 2019). Transformative capability relates to the ability to implement radical changes leading to a completely new farming system (Darnhofer, 2014; Meuwissen et al., 2019) and in some cases also a different way of living (Darnhofer, 2014 ;2021).

The concept of resilience implies to switch from the farm’s mainstream economic approaches interested in hypothetical resources optimisation under constraints, to how farms develop their adaptive capability to continually cope with change in a world with growing uncertainties due to climate change. Many authors stressed out the interest of a renewed way to analyse farming systems integrating a socio-ecological and organizational approach to consider a farm as organization endowed of resources, perceptions, preferences in a continuous process of adaptation to its environment (Van der Ploeg, 2006; Darnhofer et al., 2010; 2021; Siqueira et al., 2021).

Crop diversification is commonly considered as an important component of farms adaptive capacity (Darnhofer et al., 2010; Urruty et al., 2016; Altieri et al., 2015, 2017). Crop diversification can help farmers to cope with unexpected ecological and climatic events (Altieri et al., 2017; Gunathilaka et al., 2018) and promote options to seize new economic opportunities (Darnhofer et al., 2010; Meuwissen et al., 2019). Most of the empirical studies about the role of diversification on the improvement of farm’s adaptation are focused on biological processes related to species interactions and competition, on the assessment of farm’s diversity indicators (Martin and Magne, 2015; Bouttes et al., 2018), or on the driving factors of diversification (Pfeifer et al., 2009; Lancaster and Torres, 2019). However, few studies focus on farmers perception about the crop diversification process and its willingness to improve farm’s adaptive capacity. In particular, most of the existing literature on farmers' capacity to respond to climate change is based on case studies located in developing countries (e.g. Phuong et al., 2017; Mertz et al., 2009; Asrat and Simane., 2018), but they are not focus on a specific adaptation option, such as the diversification one.

Moreover, most of empirical studies on this subject are focused in annual crops (Meynard et al., 2018) or on agroforestry systems (Altieri, 2015), whereas there is lack of works about crop diversification on specialized orchard farms (Lancaster and Torres, 2019) mainly in vulnerable areas like the Mediterranean. Orchards are particularly challenging because of the high initial investments (price of plants, irrigation, etc), long-term return on investments, and climate risks. At the same time, orchards farmer’s diversification initiatives emerge in these zones as an important strategy to face current and future climate changes (later frost and summer drought) and economic constraints. It is worthy to understand how crop diversification activities can be implemented at the territorial scale and how farmers perceive this implementation process, mainly for bottom-up initiatives.

This paper aims to understand what aspects of crop diversification can contribute to enhancing the farmers’ adaptive capacities. In particular, we explored how crop diversification can contribute to three main aspects: (1) the robustness of the system to buffering climate, economic and workforce uncertainties; (2) the development of learning and experimentation skills; (3) adjust to societal challenges and increase farmers personal satisfactions. These aspects were analysed for the introduction of pistachio into Mediterranean orchards in the Vaucluse’s department in France.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Case Study: The Pistachio Trees on the Vaucluse Department

Case studies is well suited to the exploratory study of a particular contemporary subject on which there is little data (Yin, 2018). This approach allows for an analysis of socially complex phenomena from a holistic perspective and when there is little or no control over behavioural events (Yin, 2018). A case study allows researchers to investigate and analyse of a context placed phenomenon (Yin, 2018). This approach seems well suited for analysing how farmers perceives a crop diversification strategy as a way to enhance farm’s adaptive capacity face to current and future climate change impacts in Mediterranean orchards. Furthermore, there is little to no statistics on this topic allowing a deep analysis of the evolutive process relating crop diversification strategies and the development of farms’ adaptive capacity.

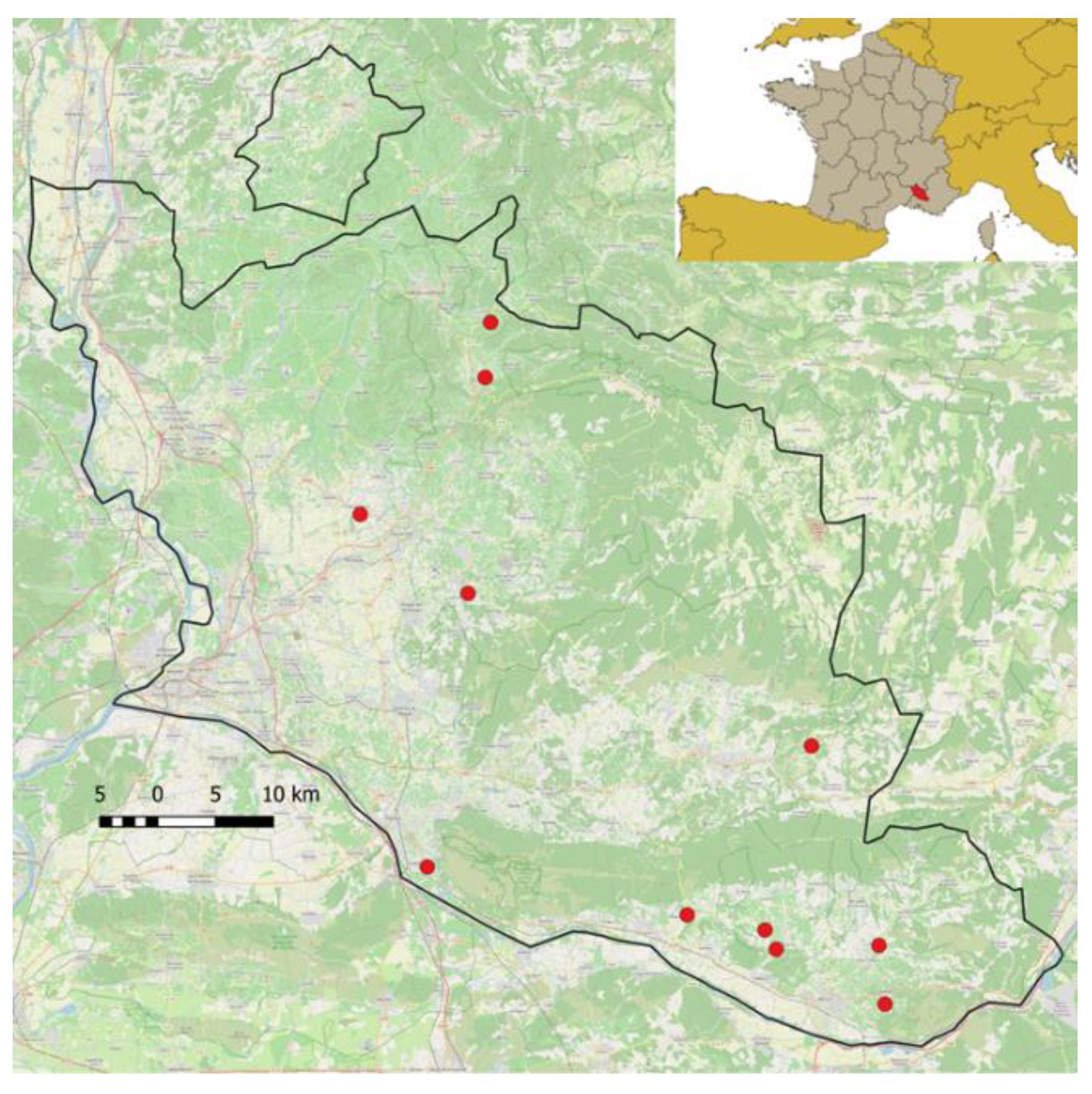

The Vaucluse department is located in south-eastern France (

Figure 1), and the overall area covers more than 3600 km

2 going from the Durance and Rhone plain around Avignon to the Mont Ventoux (1912 m above the see level—-a.s.l.). The climate is Mediterranean with well-defined seasons: hot, dry summers and mild winters. Annual precipitation is between 600 and 700 mm, spread over about 80 days, with a concentration of rainfall in autumn and spring. Wind is an important climatic feature, with an average of 128 days a year marked by the mistral (north-westerly wind), playing also on the solar radiation, which is highly evident for more than 2 800 hours per year. In terms of agricultural production, the region is characterized by a very productive plain (the Comtadine plain) where high value-added horticultural productions are located, and a hilly area with a strong presence of perennial crops, such as vineyards and orchards (currently around 60% of the total utilized agricultural area—-UAA).

On the last years, this area undergone a strong process of specialization of traditional farming systems, with a progressive abandonment of the mixed system cherry-table grapes typical of the Mont Ventoux area towards the increasing cultivation of vineyards (Scorsino and Debolini, 2020). In this context, we analysed the case study of the pistachio production (Pistacia vera L.). The plant is resistant to adverse climate conditions thanks to it physiological characteristics (Amara et al., 2017). This perennial species, already cultivated in the Mediterranean areas of Tunisia, Turkey and Spain, disappeared from France as a commercial production in the 20th century (Amir, 2020). In the last few years, few orchard farmers chose the pistachio as adaptation solution to current water stresses and later frost making difficult traditional fruit production in that region (cherry, apricot, grape, etc). In 2021, more than 30 commercial farms have pistachio trees and it represents around 50 hectares in the region.

2.2. Farmers Interviews

The local Chamber of Agriculture provided complete list of the pistachio growers in the department (n= 30). We contacted all of them and met the farmers that accepted to joining the study. We did in-depth semi-structured interviews with 12 farmers. The interviews took place between April and July 2021 and they ranged from 1h15 to 2h30. A preliminary list of questions was tested with 3 farmers before the final version of the interview guide. We reached data saturation (Fusch and Ness, 2015) with 12 interviews, because of the low number of pistachio growers at the period of the study (n= 30) and no extra information obtained after the last interviews.

The main activity of the interviewed farmers were orchards with fruits and vines productions (

Table 1). These are the main productions on the Vaucluse department (French Agricultural Census, 2010). There were only two female farmers in the group. The age of the farmers varies from 32 to 70 and the average is 48 very close to the national (49,3) and regional averages (54) (French Agricultural Census, 2010). We can also observe the most of them planted the pistachio in 2020. The average size of the pistachio orchards is 1,41 hectares but it can vary from 0,5 to 3 hectares.

We have left plenty of room for the interviewee's free expression and used a historical approach of the crop diversification through the pistachio trees: from the first time he/she thought about planting pistachio, through the implementation of the orchard until plant care nowadays. More, we have also explored three main points during the interviews:

Motivations and constraints related to the crop diversification strategy trough pistachio trees;

Main resources (actors, capital, knowledge, network, etc.) mobilized to face the challenges related to the crop diversification trough the pistachio trees;

Farmers perceptions about the climate change effects on their farms (drought, extreme temperatures, lack/ excess of water, change on plant phenology, frozen, new diseases or pests) and adaptive strategies (already in place or for the future).

We recorded and fully transcript all the interviews. Then, we focused our analysis in farmers perceptions about the role of crop diversification through the pistachio according to the literature about the adaptive capacity (Darnhofer et al., 2010; Darnhofer, 2014; Marshall et al., 2014; Meuwissen et al., 2019). We analysed how the crop diversification is related to farms adaptive strategy under climate change (

Figure 2). More into detail we analysed how the crop diversification contributes: (1) improve the robustness thanks to buffering climate, economics and workforce uncertainties; (2) develop learning and experimentation abilities; (3) adjust to societal challenges and increase personal satisfaction (

Figure 2). We use the excerpts from farmer’s interviews (verbatim) to illustrate our results.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crop Diversification to Strengthen Robustness through Improvement of Buffering Capacities

The robustness of a system is related with its capacity to resist to economic, social, environmental and institutional shocks and stresses (Meuwissen et al., 2019). System robustness is commonly associated with the buffer capacity of a system. The last is defined as the ability to assimilate a perturbation trough new inputs and marketing strategies without change the main farming structure or functions (Darnhofer, 2014). Improve farm robustness trough the buffering capacity seems an important issue to enhance farm adaptive capacity. We are mainly interested on improving the understanding of how farm pistachio diversification case can contribute to strengthen the robustness trough the improvement of the buffering capacities to (3.1.1) Climate impacts (3.1.2.) Economic and institutional uncertainties (3.1.3.) Workforce scarcity.

3.1.1. Buffering Climate Impacts through Robust Plant

Our results show that a crop diversification strategy, based on the introduction of robust species, is perceived to be a way to improve system buffer capacity to climate impacts. The buffer capacity is improved providing resistance and flexibility to face water scarcity conditions. The resistance is related to the withstanding or tolerance of perturbation (Urruty et al., 2016) by the introduction of a plant with lower water requirements requirements (De Boni et al., 2022) “Pistachios, if we don't have water we can produce. It grows everywhere, and also in very arid mountains” (A10). The flexibility is related to the ability to adapt the configuration of the system in other to limit the damages (Urruty et al., 2016). In the case of limited water availability, it can allow the farmers to allocate water use for other plants “I planted pistachio to save water to keep it for other fruits or vegetables (A10)”.

The interviewers also believe that crop diversification improve the buffer capacity face to more frequent late freezing episodes “The cherry has lot of problems with the frequent late frosts…Nuts like almonds and pistachios seems to be a solution. In particular, in the pistachio flowering is later and it can avoid late frost” (A9). A2 complemented “I planted the Kerman variety which has a late flowering time”. Crop diversification can also be a strategy to improve buffer capacity face to rising temperatures “If temperatures rise with global warming it will always be positive for pistachios. We see pistachio in warmer regions than our ones” (A12). Finally, it seems that crop diversification through pistachio improve the robustness thanks to an overall robustness of face to intense climatic events “I suffered recurring hazards (frost, hail and drought) ... I realized that every year, on my wild pistachio trees, I have fruits, no matter what happens… It is a robust tree that know how to adapt” (A11).

3.1.2. Buffering Market Uncertainties by Exploring Niche and Local Markets

Diversification also have an important role on improving the buffering capacity to market uncertainties. Market uncertainties are related with prices, costs and market access (Komarek et al., 2020). Low prices and uncertainties associated with international market seems to be perceived as an important barrier to profitability for farmers who seems to be trapped by other actors in the value chain (Bouttes et al., 2019; Siqueira et al., 2023) That is also the case for the farmer A5 “The American [pistachio] is selling at the supermarket at 11 € per kg. At this price we are not competitive with them. Moreover, industrials make promises, and then afterwards they always find good excuses.”

COVID-19 and past crises showed the unpredictability of external events in agricultural markets. Diversification to reach niche and local markets (Siqueira et al., 2023) seems to be a farm well-known strategy to risk spreading and to insure against market uncertainties (Meert et al., 2005; Darnhofer et al., 2010). Farmer A12 highlight the importance of diversification strategy to explore local and qualitative markets to buffering market uncertainties “I try to make exceptional, qualitative products and add value as much as possible. For pistachios, there is a huge local consumption and demand. In addition, the Provence appellation sells very well. […] I will sell locally for pastry, ice cream or cosmetics. The strong point of France is the quality, and we have to play on that. The pistachio for appetizers is to the Spanish and Californian producers”. Farmer A7 added “I think the investment will pay off fairly quickly. That is not the case to other productions. The situation is very favorable: French and local consumption is increasing and small and medium enterprises are looking for French ingredients to label it”. Farm A10 complemented “Everyone we know loves pistachio. I’m sure we will find French consumers interested in local and high-quality products”. Perrin and Martin, (2021) also show that after COVID-19, farmers who have already a diversified market channel had proved to have a better buffer capacity and adapted better to market uncertainties.

Finally, diversification can also be seen as a strategy to developpe a buffer capacity to institutional changes. Dervillé and Allaire, (2014), for instance, showed that changes in regulation regimes in Europe (“the end of quota system”) push many dairy farmers out of the market because of the lack of competitiveness. At the same time, Siqueira et al., (2023) showed successful farmers’ collective strategies to absorb the impacts of these institutional changes: the diversification through new brands focusing in local and niche markets.

3.1.3. Buffering Workforce Scarcity trough Mechanisation and Low-Intensive Labour Production

Crop diversification to buffering a present or expected situation of a lack of workforce is also an important mechanism to develop farm robustness and adaptability. This buffer capacity is related to the farm’s ability to organize its labour use to maintain farming activities along the time (Darnhofer, 2014). Labour availability is a struggle point to farmers leading to farmers to choose mechanisation strategies or low-labour intensive production.

Diversification through pistachio can be associated with a strategy to adapt to the lack external workforce as in the highlighted by farmer A7 “Nowadays, find labor force is very complicated in our region. People don’t want to work in the fields anymore. Pistachio is a mechanizable culture and need low interventions” or to reduce the higher workload and the risk to isolated work in the farm “I work alone on the farm, and with livestock we need to work every day. If I broke a leg for instance, it will be hard to find someone to replace me every day. I diversified through the pistachio to reduce my work” (A9). Farmer A8 added “The workload is nothing compared to vegetable production. It [pistachio] allows my children to take over the farm and to continue in their job alongside”. It can also be related workforce organizational optimization “My main activity is between March and August, after which I hit a low to restart in November. So, this would complement the activities already in place” (A11) or the optimization of farm’s machinery” This plant makes possible to reuse the available farm’s equipment, that is clear advantage” (A3).

3.2. Crop Diversification to Improving Learning Abilities

Crop diversification can also be seen as a way to enhance adaptive capacity because it is often related with the development of the abilities of learning to better face changes (Darnhofer et al., 2010; Marshall, 2014; Nguyen et al., 2016). Diversification allow farms to develop their experimentation capacities to learning by doing and learning to perceive (Nguyen et al., 2016; Darnhofer, 2021). Experimentation enable farmers to test alternatives adapted to their conditions, tinkering, monitoring and draw their own conclusions adapted (Darnhofer 2021; Siqueira et al., 2021). Agriculture as an open system under the influence of unpredictable factors asks for the abilities to learning trough experimentation to find locally adapted solutions (Darnhofer, 2014, Vogl et al., 2015, Bouttes et al., 2019). Diversification create a road to de development of individual or collective learning abilities to enhance farmer’s adaptation to climate change.

3.2.1. Develop the Abilities to Learning trough Individual Experimentations

Farmers can also see the crop diversification as an opportunity for developing their learning skills through experimentation “[Pistachio] It is a new production. I didn't want to start with preconceptions. That's why I said to myself, let’s put in place a test plot. This will tell me if it is feasible, adapted to the soil, etc. Before, the trial I made a bibliographical research, but the only thing sure is to set up locally” (A4).

Farmers also seems be motivated by the innovative and challenging content of the diversification trough the Pistachio “It's good to learn. And that's what's interesting about this project. Discover a new crop, a new plant, open up a new perspective, take on a new challenge. It's nice!” (A3). Still in the logic of a learning by experimenting with an unknown result farmer A9 said “I don't know where I'm going, of course, but on the other hand, an adventure fills a project, and projects you need to have to get up every morning”. Bouttes et al. (2019) also stressed out that diversification trough organic conversion was motived by the novelty and the opportunity to move out from the routine.

Others see a sort of opportunity to learn and test new options for the future “Pistachio is a small R&D plot. It's a bet on the future” (A4). Farmer A11 added “I like to thinking and anticipate developments, I said to myself, why not see if it's possible. I saw this project as an adventure and a shared experimentation. The capacity to plan, experiment and learn in face of the change is important to seize opportunities (Darnhofer et al. 2010).

Finally, we show that crop diversification can contribute to develop learning abilities. In line with Van der Ploeg et al., (2006), Darnhofer et al., (2010) and Nguyen et al., (2016) our results show that learning abilities developed thanks to crop diversification is understanding as a way to deal with important challenges. More, throughs experimentation of novelties it can also be a way to learning to perceive the impacts and enhance their adaptive capacity. It is also seen as a way to transform challenges in opportunities by an on-going recombination of social and material resources (Van der Ploeg et al., 2006; Siqueira et al., 2021).

3.2.2. Develop the Abilities to Learning through Collective Experimentation

Peers’ exchange seems to be the main way to share experience and promote collective learning. Social media seems to be the main way to promote collective learning “[In the WhatsApp group] We discuss the problems we can have (frozen, lack of nutrients, prune methods, diseases, etc.), we also give each other advices and we try to think together about what to do, when, why and how. We also exchange photos to show our pistachio plants” (A2). It can be done through collective field training “When I planted, I didn't know how to prune pistachio trees. We went to training in A5 farm and a Spanish engineer came and explained us how to prune the trees”. Study tours in other countries also seems an important way to get information in this collective experimentation “Then we went to Spain, Greece, I contacted my friends in Italy, California, everyone helped me. (A5). Farmer A3 added “We went to Spain with many questions and we come back with still more questions. I haven't heard anyone say that they haven't learned”.

The interactions between different organisations promoting diversification through pistachio is also seen as collective experimentation as farmer A6 suggested “We are all leaning together. The advisors from the chamber of agriculture, the farmers; the pistachio association, the pistachio farmers’ union…We are all in the same boat!”. Farmer A6 develops about the collective structuration of the project “I did bibliographic research in the archives of Avignon and Marseille, then with former professionals, gardeners, etc, a real treasure hunt game! […] After we created the association, everyone got involved, we were motivated for this collective project”. Farmer A12 complemented “In addition, the plant nursery found the plants to us, the “Association Pistache in Provence” organized the study trip in Spain. We also recently created a farmer union to represent pistachio growers (A12)”.

The collective project is also supported by public organisations as explained by Farmer A12 “The DRAF follows us and make possible to advance with chemicals tests and temporary approvals”. Farmer A3 complement “I'm pretty confident, because the chamber mobilizes resources and technicians to follow us” (A3). The farmer A10 also mentioned the credibility of the collective experimentation. “The collective organization behind the project is an asset, a strength, to solve technical problems. Even, it gave me more insurance to plant pistachio. Together we have a weight” (A11) farmer A10 complemented “When we saw all the local famous agricultural personalities who planted, we said that if they plant the sector will start. It reassured us right in!” (A10).

Our results are in line with the literature showing that a diversity of sources of knowledge from experiential and experimental can benefit farmers learning (Darnhofer et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2016). These authors also highlight that discuss new ideas with other people can allow farmers to interpret and explain a phenomenon in a different way and thus discover new ways to act. Our results also corroborate (Bouttes et al., 2019) showing that learning trough experimentation, seems to be enhanced by a collective organisation. As Darnhofer (2014; 2021) and Siqueira et al., (2021; 2023) our study highlights the importance of farmers’ ability to mobilize external resources through a collective action to build up a collective experimentation based in mutual help and exchanges. Indeed, farmers state that group discussions allow them to increase they learning abilities thanks to the process of building up common methods, implement these methods, analyse the results to find out common insights in a collective experimentation.

3.3. Crop Diversification to Adjust to Change and to Increase Satisfaction

Crop diversification can also be seen as way to enhance adaptive capacity to face a changing and unpredictable environment. The ability to cope with change means to be aware of internal and external drivers of changing and develop a capacity to transform to evolve with (Darnhofer 2014; 2021; Marshall et al., 2014, Meuwissen et al., 2019). Therefore, diversification is connected with changes in the decision’s rules due to context change or due to changes in personal perceptions and preferences (Darnhofer et al., 2010). More than financial, familiar and emotional issues are also associated with behaviour change to adapt and increase farmers’ personal satisfaction.

3.3.1. Crop Diversification to Cope with Societal Issues

Farmer’s see crop diversification through the pistachio as a way to better cope with multiple societal issues. As Bouttes et al., (2019) few farmers refer to actively engage with societal demands and do not perceive it like a burden to be endured “The idea is to adapt to society. I tried to be in the vanguard” (A9). Coping with ecological issues seems to be important for few farmers “There is many environmental issues, you can hear all the time in the news” (A10). More specifically about the water issues in the region the farm A10 added “When we know the problems we will have in terms of water management in the future. I find it absurd to plant irrigated crops. Pistachio is supposed to work well without irrigation”. But he also highlights that many farmers do not few concerned about ecological issues and few attached to them believes mainly related with irrigation and water issues “We planted pistachio without irrigation to save water. We tell ourselves that we are doing our part but when we look around our surroundings, it’s not the same! Goulet and Vinck (2012) highlights that changing practices is perceived as a necessity to keep connected with societal and environmental changes:

Diversification trough pistachio production is also a way to deal with important institutional changes related to societal demands to chemical-free production. Farmer A3 explained “With the frequent evolutions in chemical authorizations. We are reaching a limit for many crops and we will not be able to keep some productions in the farm anymore. I need to diversify and pistachio seems a good candidate”. Farmer A4 complemented “Pistachio seems to be less susceptible to diseases and insects. So, we will not need to do many chemicals to manage these problems”. These results are in line with the perception of farmers that considers that spreading chemicals as a burden (Chantre et al., 2015; Bouttes et al., 2019).

3.3.2. Crop Diversification to Increase Farmers’ Satisfaction

Farmers see crop diversification as a way to put in place a project to increase individual and family’s satisfaction. Farmers related increased satisfaction through a personal affection to the plant “Pistachio trees are really beautiful. It's been 2 years since I listed trees in the nature, then I went to photograph them. So, I followed them throughout the year, to see how they were evolving, to see the inflorescence” (A10). Farmer A6 added, when I went to Spain and Greece I found the tree very beautiful and then I told to my-self ‘Why not to grow this plant in my farm” (A6). The personal affection related to a diversification project was commonly highlighted in the literature (Bouttes et al., 2019; Siqueira et al., 2021)

Indeed, maintaining the quality of life and work satisfaction for all members of the farm family is a core consideration to farmer’s (Darnhofer, 2014; 2021; Siqueira et al., 2021). Our results, also shows that family’s satisfaction is also in the core of crop diversification choice as explained by farmer (A9) “My family were always telling me, mom you work a lot, I should stop a bit. I never take holidays. This kind of comments push me to find solutions. I believe that the pistachio can be a solution. My youngest boy is starting to take more interest in the farm, he says if there is something other than the sheep, why not to take over the farm. My husband doesn’t like the heard either, he’s not from a farming background. But in the pistachio project he fully supports and helps me!” (A9). Farmers that perceive their practices as problematic are actively looking for alternatives (Chantre et al., 2015). Bouttes et al. (2019) showed that diversification, through organic conversion, is perceived as an opportunity to increase personal satisfaction due to workload reduction and as a way to maintain family farming

Other farmers also see the diversification trough the pistachio as symbolic way to let some heritage “Today we plant an apple tree, apricot, etc. and we tear them after maximum 10 years. We like the fact that [pistachio] it is a tree that can become a hundred years old, or even bicentenary. I like the idea of leaving a mark for my grand-children and for the future generations” (A10).

4. Conclusions

Climate change impacts are leading farmers to diversify specialized farming systems, mainly in most vulnerable areas like the Mediterranean. Crop diversification trough the introduction of new species of plants in orchards is considered an important adaptive strategy to face these impacts. Despite, little attention has been paid in the literature. The case of the crop diversification trough the introduction of pistachios in Vaucluse’s orchards witness this phenomenon and bring new insights to that topic. This paper explored farmers’ perceptions on crop diversification trough pistachio as a strategy to enhance farm’s adaptive capacity under climate change conditions.

The results show that crop diversification is supposed to enhance 3 main components of farms adaptative capacity: (1) strengthening robustness through improvement of buffering capacities to climate impacts (trough robust and adapted plants), economic uncertainties (by exploring local/niche markets) and labour scarcity (by lowering workforce requirements and mechanization); (2) Learning by experimenting, monitoring and exchanging with pairs and advisors (3) Cope with change related with societal demands and increase personal satisfaction.

Finally, the results also showed that crop diversification is not only seen as an agronomic advantage to farmers. Diversification is also related to a farm’s systemic strategy to enhance its adaptive capacity through the development of this multiple farm’s components. To improve the efficiency of diversification targeted policies it seems important to facilitate the understanding and encourage the development of farm’s adaptive capacity components.

To go further on the research about the role of the diversification to enhancing farms’ adaptive capacity we propose to combine two main approaches.. First, it would be insightful to assess the level of importance of each aspect of the adaptive capacity to each farm to better consider heterogeneity in farms’ profiles and preferences. Second, it also would be useful to develop a comparative study in other regions and about other productions. The combination of the approaches allows to better identify and explore territorial and sectoral lock-ins to the development of crop diversification strategies. Moreover, these approaches allow us to identify local strategies to enhance farm’s adaptive capacities considering farm’s heterogeneity and territorial specificities.

References

- Altieri, M.A.; Nicholls, C.I.. The adaptation and mitigation potential of traditional agriculture in a changing climate. Clim. Change 2017, 140, 33–45. [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Nicholls, C.I.; Henao A.; Lana M.A. Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 869-890. [CrossRef]

- Amara, M.; Bouazza, M.; Al-Saghir, M.G. Anatomical and adaptation features of Pistacia atlantica Desf. to adverse climate conditions in Algeria. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 137-153. [CrossRef]

- Amir, M. Le pistachier: Un arbre d’avenir – Histoire, culture et cuisine. Ed. Rustica Editions, Paris, FR, 2020; 128 p.

- Asrat, P.; Simane, B. Farmers’ perception of climate change and adaptation strategies in the Dabus watershed, North-West Ethiopia. Ecol Process. 2018, 7, 7.

- Bouttes, M.; Darnhofer, I.; Martin, G. Converting to organic farming as a way to enhance adaptive capacity. Org. Agric. 2019, 9, 235–247.

- Bouttes M.; Cristobal M.S.; Martin, G. Vulnerability to climatic and economic variability is mainly driven by farmers’ practices on French organic dairy farms. Eur. J. Agron. 2018, 94, 89-97.

- Chantre, E.; Cerf, M.; Le Bail, M. Transitional pathways towards input reduction on French field crop farms. Int. J. Agric Sustain. 2015, 13, 69–86. [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I; Bellon, S.; Dedieu, B.; Milestad, R. Adaptiveness to enhance the sustainability of farming systems. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 30, 545–555. [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I. Resilience and why it matters for farm management. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2014, 41, 461–484. [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I. Resilience or how do we enable agricultural systems to ride the waves of unexpected change? Agric. Syst. 2021, 187, 102997.

- De Boni, A.; D’Amico, A.; Acciani, C.; Roma, R. Crop Diversification and Resilience of Drought-Resistant Species in Semi-Arid Areas: An Economic and Environmental Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9552.

- Fader, M.; Giupponi, C.; Burak S.; Dakhlaoui, H.; Koutroulis, A.; Lange, M.A.; Llasat, M.C.; Pulido-Velazquez, D.; Sanz-Cobeña, A. Water. In: Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin – Current Situation and Risks for the Future. First Mediterranean Assessment Report; Cramer,W.; Guiot, J.; Marini, K.; Ed. Union for the Mediterranean, Plan Bleu, UNEP/MAP, Marseille, France, 2020, p 57.

- Fader, M.; Shi, S.; von Bloh, W.; Bondeau, A.; Cramer, W. Mediterranean irrigation under climate change: more efficient irrigation needed to compensate for increases in irrigation water requirements, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 20, 953–973.

- Fraga, H.; Atauri I.G.C.; Santos J.A. Viticultural irrigation demands under climate change scenarios in Portugal. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 196, 66-74.

- French Agricultural Census (2010) – Recensement Agricole 2010.

- Funes, I.; Savé, R.; Herralde, F.; Biel, C.; Pla, E.; Pascual, D.; Zabalza, J.; Cantos, G.; Borràs, G.; Vayreda, J.; Aranda, X. Modeling impacts of climate change on the water needs and growing cycle of crops in three Mediterranean basins, Agric. Water Manag., 2021, 249, 106797.

- Fusch, P.I.; Ness, L.R. Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research. The Qualitative Report 2015, 20, 9, 1408-1416. [CrossRef]

- Gordo, O.; Sanz, J.J. Impact of climate change on plant phenology in Mediterranean ecosystems, Glob. Change Biol., 2010. 16, 3, 1082-1106. [CrossRef]

- Goulet, F.; Vinck, D. L’innovation par retrait. Contribution à une sociologie du détachement. Innovation by withdrawal. Contribution to a sociology of detachment. Revue Française de Sociologie 2012, 53, 195.

- Gunathilaka, R.P.D.; Smart, J.C.R.; Fleming, C.M. Adaptation to climate change in perennial cropping systems: Options, barriers and policy implications. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2018, 82, 108-116. [CrossRef]

- Gurgel, A.C.; Reilly, J.; Blanc, E. Challenges in simulating economic effects of climate change on global agricultural markets. Clim. Change, 2021, 166, 29. [CrossRef]

- Ioannidou, S.; Litskas, V.; Stavrinides, M.; Vogiatzakis, I.Ν. Placing Ecosystem Services within the Water–Food–Energy–Climate Nexus: A Case Study in Mediterranean Mixed Orchards. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2224.

- Ivits, E.; Cherlet, M.; Tóth, G.; Sommer, S.; Mehl, W.; Vogt, J., Micale, F. Combining satellite derived phenology with climate data for climate change impact assessment. Glob. Planet. Change, 2012, 88-89, 85-97.

- Karimi, V.; Karami, E.; Karami, S.; Keshavarz, M.. Adaptation to climate change through agricultural paradigm shift. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 5465–5485.

- Komarek A.M.; De Pinto, A.; Smith, V.H. A review of types of risks in agriculture: What we know and what we need to know. Agric. Syst. 2020, 178, 102738.

- Lancaster, N.A.; Torres, A.P. Investigating the Drivers of Farm Diversification Among U.S. Fruit and Vegetable Operations. Sustainability, 2019, 11, 3380.

- Lereboullet, A-L.; Beltrando, G.; Bardsley, D.K. Socio-ecological adaptation to climate change: A comparative case study from the Mediterranean wine industry in France and Australia, Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 164, 273-285.

- Legave, J.M.; Blanke, M.; Christen, D; Giovannini, D.; Mathieu, V.; Oger, R. A comprehensive overview of the spatial and temporal variability of apple bud dormancy release and blooming phenology in Western Europe. Int J Biometeorol, 2013, 57, 317–331.

- Meert, H.; Van Huylenbroeck, G.; Vernimmen, T.; Bourgeois, M.; van Hecke, E. Farm household survival strategies and diversification on marginal farms. J. Rural Stud. 2005, 21, 81-97. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, N. A.; Stokes, C.J.; Webb, N.P.; Marshall, P.A.; Lankester, A.J. Social vulnerability to climate change in primary producers: A typology approach. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 186, 86–93. [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Magne, M.A. Agricultural diversity to increase adaptive capacity and reduce vulnerability of livestock systems against weather variability – A farm-scale simulation study. Agric., Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 199, 301–311. [CrossRef]

- Mertz, O.; Mbow, C.; Reenberg, A.; Diouf, A. Farmers’ Perceptions of Climate Change and Agricultural Adaptation Strategies in Rural Sahel. Environ. Manag., 2009, 43, 804–816.

- Nguyen, T.P.L., Seddaiu, G.; Virdis, S.G.; Tidore, C.; Pasqui, M.; Roggero, P.P. Perceiving to learn or learning to perceive? Understanding farmers’ perceptions and adaptation to climate uncertainties, Agric. Syst. 2016, 143, 205–216.

- Meynard, J.-M.; Charrier, F.; Fares, M.; Le Bail, M.; Magrini, M.-B.; Charlier, A.; Messéan, A. Socio-technical lock-in hinders crop diversification in France. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 54.

- Meuwissen, M.; Feindt, P.; Spiegel, A.; Termeer, C.; Mathijs, E.; de Mey, Y.; Finger, R.; Balmann, A.; Wauters, E.; Urquhart, J.; Vigani, M.; Zawalinska, K.; Herrera, H.; Nicholas-Davies, P.; Hansson, H.; Paas, W.; Slijper, T.; Coopmans, I.; Vroege, W.; Ciechomska, A.; Accatino, F.; Kopainsky, B.; Poortvliet, P.M;, Candel, J.; Maye, D.; Severini, S.; Senni, S.; Soriano, B.; Lagerkvist, C.-J.; Peneva, M.; Gavrilescu, C.; Reidsma, P. A framework to assess the resilience of farming systems. Agric. Syst. 2019 176, 102656. [CrossRef]

- Morugán-Coronado, A.; Linares, C.; Gómez-López, M.D.; Faz, Á.; Zornoza, R. The impact of intercropping, tillage and fertilizer type on soil and crop yield in fruit orchards under Mediterranean conditions: A meta-analysis of field studies. Agric. Syst. 2020. 178, 102736. [CrossRef]

- OECD Environmental Outlook to 2050. OECD Publishing, 2012.

- Pfeifer, C.; Jongeneel, R.A.; Sonnevelda, M.P.W.; Stoorvogel J.J. Landscape properties as drivers for farm diversification: A Dutch case study. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 1106–1115.

- Perrin, A.; Martin, G. Resilience of French organic dairy cattle farms and supply chains to the Covid-19 pandemic. Agric. Syst. 2021, 190, 103082.

- Phuong, L.T.H.; Biesbroek, G.R.; Sen, L.T.H.;Wals, A.E.J. Understanding smallholder farmers’ capacity to respond to climate change in a coastal community in Central Vietnam. Climate and Development, 2018, 10, 701–716.

- Pouffary, S.; de Laboulaye, G.; Antonini, A.; Quefelec, S.; Dittrick, L. Rapport Scientifique. Les Défis du changement climatique en méditerranée. Mediterranean experts on climate and environmental change, 2019, p 188.

- Scorsino, C.; Debolini, M. Mixed Approach for Multi-Scale Assessment of Land System Dynamics and Future Scenario Development on the Vaucluse Department (Southeastern France), Land, 2020. 9, 180. [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, T.T.d.S.; Galliano, D.; Nguyen, G.; Bánkuti, F.I. Organizational Forms and Agri-Environmental Practices: The Case of Brazilian Dairy Farms. Sustainability, 2021 13, 3762. [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, T.T.S.; Gonçalves, A.; Bouroullec-Machado M.; Mur, L. Governance of sustainability standards in new farmers collective’s brands: the case of Occitania dairy sector. Farmers’ brands and sustainability standards, Cahiers Costech, 2023, 6.

- Slijper, T.; Mey, Y.;.Poortvliet, P. M.; Meuwissen, M.P.M. Quantifying the resilience of European farms using FADN, Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2022, 49, 121–150.

- Tack, J.; Barkley, A.; Rife, T.W.; Poland, J.A.; Nalley, L.L. Quantifying variety-specific heat resistance and the potential for adaptation to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22: 2904-2912.

- Urruty N.; Tailliez-Lefebvre D.; Huyghe C. Stability, robustness, vulnerability and resilience of agricultural systems: A review Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 15.

- Van der Ploeg, J. D.; Verschuren, P.; Verhoeven, F.; Pepels, J. Dealing with novelties: a grassland experiment reconsidered. J. Environ. Policy Plan., 2006, 8, 199 –218.

- Vanschoenwinkel J.; Moretti, M.; Van Passel, S. The effect of policy leveraging climate change adaptive capacity in agriculture. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2019, 47, 138–156. [CrossRef]

- Vernooy, R. Does crop diversification lead to climate-related resilience? Improving the theory through insights on practice. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 46, 877–901. [CrossRef]

- Vogl, C.R.; Kummer, S.; Leitgeb, F.; Schunko, C.; Aigner, M. Keeping the actors in the organic system learning: the role of organic farmers’ experiments. Sustain. Agric. Res. 2015, 4, 140–148. [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case study research and applications: design and methods. Sixth Edition. SAGE Publications, 2018, Inc. Los Angeles.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).