Submitted:

17 July 2024

Posted:

18 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

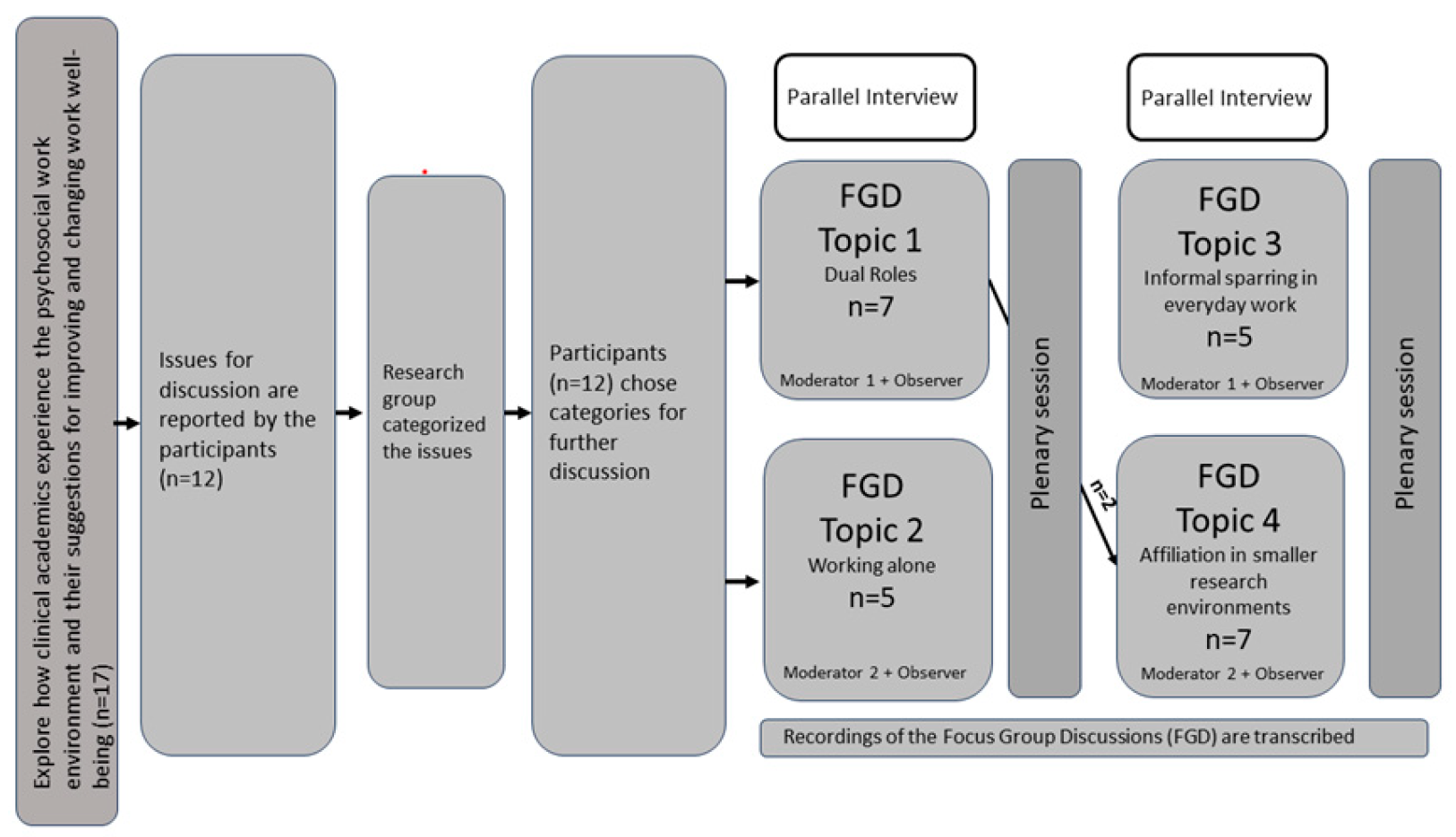

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approvals

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

3.2. Main Theme: Lack of Integration of Research in Clinical Practice

3.3. Theme I: The Fine Line between Research and Clinical Practice

3.4. Theme II: A Wish to Belong

3.5. Theme III: The Impact of Motivational Factors and Role Models

4. Discussion

Methodological Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raine, G.; Raine, G.; Evans, C.; Evans, C.; Uphoff, E.P.; Uphoff, E.P.; Brown, J.V.E.; Brown, J.V.E.; Crampton, P.E.S.; Crampton, P.E.S.; et al. Strengthening the clinical academic pathway: a systematic review of interventions to support clinical academic careers for doctors and dentists. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aspinall, C.; Slark, J.; Parr, J.; Pene, B.; Gott, M. The role of healthcare leaders in implementing equitable clinical academic pathways for nurses: An integrative review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, A.M. The National Institutes of Health Physician-Scientist Workforce Working Group Report: A Roadmap for Preserving the Physician-Scientist. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2014, 7, 289–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health NIo. Physician-scientist workforce working group report. 2014. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health 2021.

- Health MotIa. The government is launching several initiatives in the emergency plan for the healthcare system [Regeringen lancerer flere initiativer i akutplan for sundhedsvæsenet]. Website of the Ministry of the Interior and Health of Denmark, 2023:1-2.

- Labrague, L.J.; McEnroe-Petitte, D.M.; Leocadio, M.C.; Van Bogaert, P.; Cummings, G.G. Stress and ways of coping among nurse managers: An integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 1346–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eva, G.; Amo-Setién, F.; César, L.; Concepción, S.; Roberto, M.; Jesús, M.; Carmen, O. Effectiveness of intervention programs aimed at improving the nursing work environment: A systematic review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2023, 71, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silistraru, I.; Olariu, O.; Ciubara, A.; Roșca. ; Alexa, A.-I.; Severin, F.; Azoicăi, D.; Dănilă, R.; Timofeiov, S.; Ciureanu, I.-A. Stress and Burnout among Medical Specialists in Romania: A Comparative Study of Clinical and Surgical Physicians. Eur. J. Investig. Heal. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, G.A.B.; Lantheaume, S.; Fiault, R.; Shankland, R. Mindfulness-Based Programs Improve Psychological Flexibility, Mental Health, Well-Being, and Time Management in Academics. Eur. J. Investig. Heal. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 1035–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sermeus, W.; Smith, H.L.; Kutney-Lee, A.; van den Heede, K.; Sloane, D.M.; Busse, R.; McKee, M.; Bruyneel, L.; Rafferty, A.M.; et al. Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: cross sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States. BMJ 2012, 344, e1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization & Burton, J. WHO healthy workplace framework and model: background and supporting literature and practices. Geneva: World Health Organization 2010:93 p.

- Buch A, Andersen V, Sørensen OH. Knowledge work and stress: between excitement and strain [Videnarbejde og stress: mellem begejstring og belastning]: Jurist-og Økonomforbundets Forlag 2009.

- Fisher, CD. Conceptualizing and measuring wellbeing at work. In: Cooper PYCaCL, ed. Work and wellbeing Wiley Blackwell 2014:9-93.

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker AB, Demerouti E. Job demands-resources theory. Work and wellbeing, Vol III. Hoboken, NJ, US: Wiley Blackwell 2014:37-64.

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory. Handbook of theories of social psychology, Vol 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd 2012:416-36.

- Berndt, J.D.; Ortelli, T.A.P. Creating a Healthy Work Environment. AJN, Am. J. Nurs. 2023, 123, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copanitsanou, P.; Fotos, N.; Brokalaki, H. Effects of work environment on patient and nurse outcomes. Br. J. Nurs. 2017, 26, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliman, M.; Aljezawi, M. Nurses’ work environment: indicators of satisfaction. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinsky, C.A.; Biddison, L.D.; Mallick, A.; Dopp, A.L.; Perlo, J.; Lynn, L.; Smith, C.D. Organizational Evidence-Based and Promising Practices for Improving Clinician Well-Being. NAM Perspect. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, E.; Jones, A.A.; Sivapragasam, M.; Nath, S.; Mak, L.E.M.; Rosenblum, N.D.M. The Integration of Clinical and Research Training: How and Why MD–PhD Programs Work. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzea, V.-E.; Mechili, E.A.; Melidoniotis, E.; Petrougaki, E.; Nikiforidis, G.; Argyriadis, A.; Sifaki-Pistolla, D. Recommendations for young researchers on how to better advance their scientific career: A systematic review. Popul. Med. 2022, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazeley, P. Defining 'Early Career' in Research. High. Educ. 2003, 45, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, K.J. , Wichmann-Hansen G., T.K. J. Quality in Ph.D. courses [Kvalitet i ph.d.-forløb]. Aarhus: Aarhus University, 2014:1-144.

- Chevalier JM, Buckles D. Participatory Action Research: Theory and Methods for Engaged Inquiry: Routledge 2013.

- Holden, R.J.; Scott, A.M.M.; Hoonakker, P.L.T.; Hundt, A.S.; Carayon, P. Data collection challenges in community settings: insights from two field studies of patients with chronic disease. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, A. Participatory Action Research: SAGE Publications 2008.

- Patton, MQ. Choosing a Sample: The Logic of Purposeful Sampling. In: MQ P, ed. Program evaluation Kit How to Use Qualitative Methods in Evaluation. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications, Inc. 1987:44-70.

- Halkier, B. Focus groups as social enactments: integrating interaction and content in the analysis of focus group data. Qual. Res. 2010, 10, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B. Clinical-academic partnerships research: converting the rhetoric into reality. . 2005, 11, 1218–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.; Bradbury, A.; Shortland, S.; Hewett, F.; Storey, K. Clinical academic careers for general practice nurses: a qualitative exploration of associated barriers and enablers. J. Res. Nurs. 2021, 26, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, K.R.; Strohschein, F.J.; Horill, T.C.; Lambert, L.K.; Powell, T.L. A survey of nurses' experience integrating oncology clinical and academic worlds. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2840–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hølge-Hazelton, B.; Kjerholt, M.; Berthelsen, C.B.; Thomsen, T.G. Integrating nurse researchers in clinical practice - a challenging, but necessary task for nurse leaders. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trusson, D.; Rowley, E. Qualitative study exploring barriers and facilitators to progression for female medical clinical academics: interviews with female associate professors and professors. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oostveen, C.J.; Goedhart, N.S.; Francke, A.L.; Vermeulen, H. Combining clinical practice and academic work in nursing: A qualitative study about perceived importance, facilitators and barriers regarding clinical academic careers for nurses in university hospitals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 4973–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.V. What motivates radiographers to start working with research? Radiography 2022, 29, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, P.A.; Gallimore, D.; Jordan, S. Transition from clinician to academic: an interview study of the experiences of UK and Australian Registered Nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichaud-Ekstrand, S. New Brunswick nurses' views on nursing research, and factors influencing their research activities in clinical practice. Nurs. Heal. Sci. 2016, 18, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Christensen, M. Positive Participatory Organizational Interventions: A Multilevel Approach for Creating Healthy Workplaces. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 696245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Yarker, J.; Munir, F.; Bültmann, U. IGLOO: An integrated framework for sustainable return to work in workers with common mental disorders. Work. Stress 2018, 32, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Heal. Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malterud, K. The art and science of clinical knowledge: evidence beyond measures and numbers. Lancet 2001, 358, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malterud, K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 2001, 358, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Organized Topics | Submitted Issues |

| Dual roles | Motivation Work life balance |

| Working alone | Loneliness Working from home versus working at the office (pros & cons) Structuring administrative tasks, emails, and research tasks. |

| Employment conditions | Terms of employment (Part time/temporary employment) Insecurities towards future employment |

| Informal sparring in everyday work | Collaboration Cooperation Missing/lack of recognition Colleagueship |

| Affiliation in smaller research environments | Competitive environment Sharing knowledge Chemistry between main supervisor and PHD student New employees’ experiences of inclusion in the research environment |

| Organized Topics | Submitted Issues |

| Dual roles |

Motivation Work life balance |

| Working alone | Loneliness Working from home versus working at the office (pros & cons) Structuring administrative tasks, emails, and research tasks. |

| Employment conditions | Terms of employment (Part time/temporary employment) Insecurities towards future employment |

| Informal sparring in everyday work |

Collaboration Cooperation Missing/lack of recognition Colleagueship |

| Affiliation in smaller research environments | Competitive environment Sharing knowledge Chemistry between main supervisor and PHD student New employees’ experiences of inclusion in the research environment |

| Participants (P#)1 | Age (years) | Sex | Education | Position | Focus Group (#) | Employed2 (Months) | ||

| P1 | 33 | Male | Physician | PHD student | 1 | 3 | 36 | |

| P2 | 53 | Female | Nurse | Adjunct | 2 | 4 | 48 | |

| P3 | 30 | Female | Nurse | PHD student | 2 | 4 | 15 | |

| P4 | 29 | Male | Physician | PHD student | 2 | 4 | 6 | |

| P5 | 39 | Male | Physician | PHD student | 1 | 3 | 15 | |

| P6 | 62 | Male | Nurse | Adjunct | 1 | 3 | 108 | |

| P7 | 31 | Female | Pharmacist | PHD student | 1 | 4 | 14 | |

| P8 | 44 | Female | Radiographer | Associated professor | 1 | 4 | 140 | |

| P9 | 32 | Female | Physician | PHD student | 2 | 4 | 24 | |

| P10 | 36 | Female | Physician | PHD student | 1 | 3 | 25 | |

| P11 | 38 | Female | Physician | PHD student | 2 | 4 | 24 | |

| P12 | 36 | Male | Physician | PHD student | 1 | 3 | 14 | |

| Codes | Sub-Themes | Theme | Main Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double workload Time management is hard with unpredictable tasks and cloudy functions The researcher’s choice has consequences and risks for individuals and patients Focus on the positive in combining research and clinic to manage stress Leadership responsibilities |

Dissolved boundaries between the two functions makes navigation necessary. Unclear task functions results in potential consequences, self-management strategies, and a need for support from leaders |

The fine line between research and clinical practice |

Lack of integration of research in clinical practice |

| Need of fellowship ‘No’ generates an internal conflict. Difficult choices affect work well-being It takes a certain someone who has certain skills |

Loneliness is decreased by sparring and collaboration Dilemmas emerge between duty and personal interest |

A wish to belong | |

| Competition drives effort and pushes to keep you going Incongruent expectations and interests Progression, workflow, and autonomy are motivational factors Structure and fellowship maintain motivation Sparring, reaching out and connecting in a broader network can be difficult, but is needed Companionship increases motivation to succeed |

Competition is a killer and a driver Reinforce motivational factors Impact of role models |

The impact of role models and motivational factors |

| Themes | Quotes (samples) |

|---|---|

| The fine line between research and clinical practice | P6: Some believe that those in research and clinic go hand in hand - and that there is not much of a difference P1: I think it can be rather stressful, even though you don’t physically have to be in the clinic, you still need to do the patient work, such as their tests, and all of my patients get bloodwork done and the results end up in my mailbox. So, if you have somewhat of a conscience, then you have to be in control of the test. Even though you actually are in the middle of a week delegated for research P4: You have obligations, which applies to all with clinical research, the issue is, that we have an additional job, which has nothing to do with the clinic. P5: … It (research) should not affect the patients. P9: Time – for the clinic, those days disappear, and you cannot continue with funding application and project. On the other hand, the clinic affects research days, because there is something with a patient, which cannot wait. So, if I am not strict with time, then you are easily absorbed P5: It’s hard to say no - I frequently find myself in departments where numerous studies are incorporated into everyday practice. This blurs the distinction between being solely a clinician; suddenly, one becomes involved in research P12: It is a management task to tell the hospital department what the researcher should use their time on, and that they should not plan other tasks for the person P11: Tips could be to make a bullet journal, which clearly illustrates when to do what, but also allows for marking the tasks as completed or removing them once finished. It grants the experience of momentum |

| A wish to belong | P7: It is hard even though you are physically together – it is a feeling of loneliness, it can be lonely to sit with your own when you research different things… you sit with your own challenges P9, P3: If you are barely in the clinic, then you will not be a part of the fellowship they already have P9: I have been there two days, but I have no clue what is going on. You become an outsider P5: … That it is not just me who is researching, but it is the whole department who is researching. Everyone is part of the research – and that we remember to celebrate all our victories P3: Being in the clinic is a breather - being together with others, having one's colleagues again P5: It's important to have others whom I can casually chat with, informally discussing issues I face P2: We should not underestimate the relational aspect of formal as well as informal meetings P4: … If you want a research unit to work, then you have to put aside your own needs P3: I have accepted the fact that, even when you do it as well as you possibly can, then you still cannot do it on time P8: ... But you must be able to endure the environment |

| The impact of role models and motivational factors | P4: I believe that within the medical field, competition is everywhere, however, it is the level of competition that changes across each field of research. I worked incredibly much, also more than what I thought was comfortable, I knew I was controlled by the competition in my daily work. … Being first in the field is our goal; we aim for the highest impact. It should be the first thing published. … When I have a combined position, there are expectations from both sides regarding the clinical part and the research part P3: There is also a prioritization of what is most important in the themes one researches. It is controlled by the main supervisor's interests and the competition regarding which focus is emphasized. It would be nice if everyone had equal opportunities, including those who were not highlighted as much P8: Our positioning is at stake; we thrive on being involved and being present, and it is really tough P4: Personally, I would like a work life where I thrive, and if I keep ending up in situations where I need to say yes and no because I want to succeed with my research, then I do not think one publication can weigh up for it. It is important that I have others who I can small talk with, talk informally about the problems I face P2: Something, which I need, is constructive feedback. I do not need to hear that I am a clown. I approach people best if I feel like I have a good relationship P7: We have a fine work environment. It is the projects, i.e. advising, sparring, where we have a common ground P6: We must have a binding sense of responsibility towards each other, which is currently missing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).