Submitted:

18 July 2024

Posted:

19 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Statistical Analysis

2.2. Analysis of Free-Text Answers

3. Results

3.1. Predictors of Psychological Distress

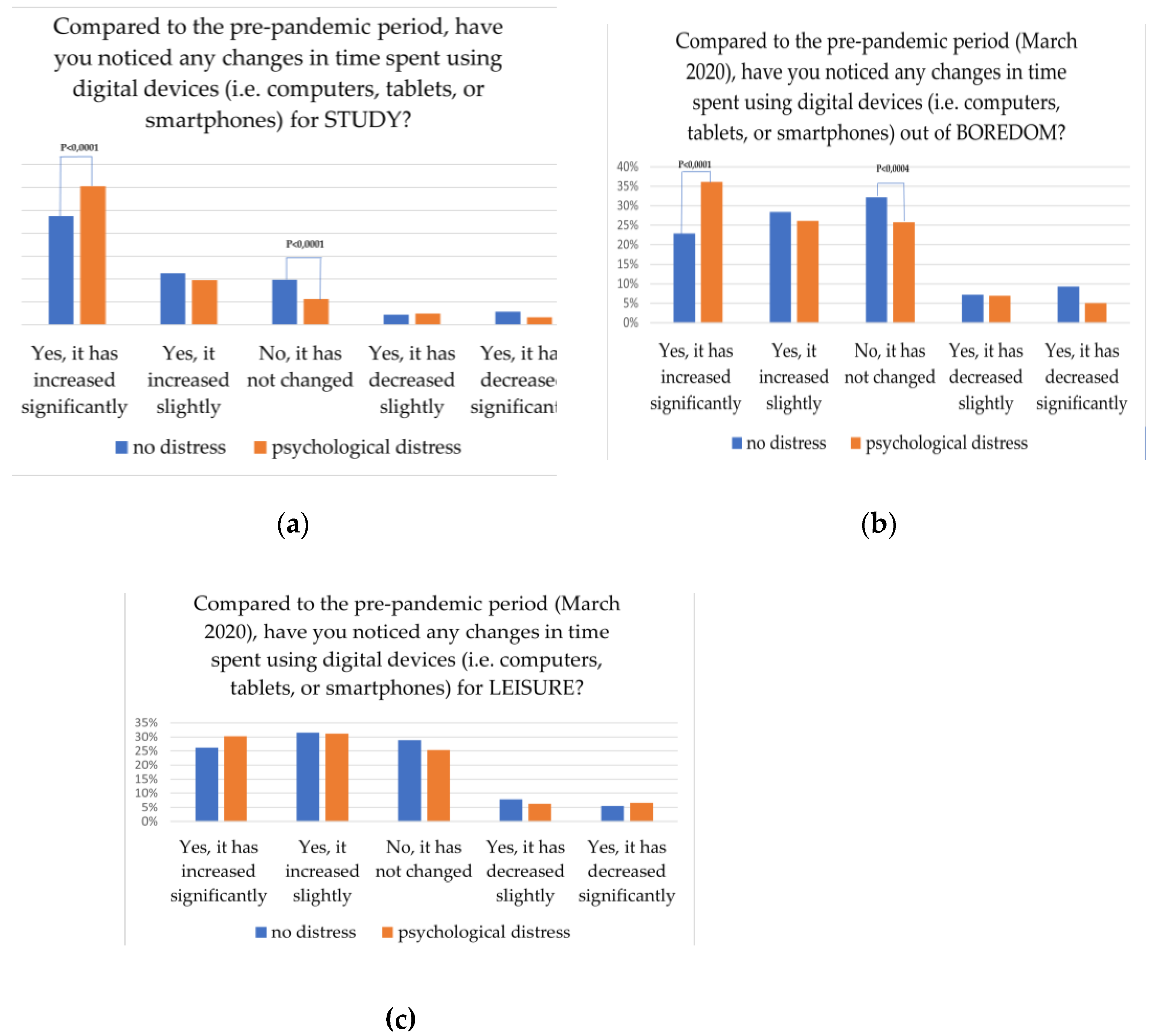

3.2. Time Spent on Device According to Possible Presence of Psychological Distress

3.3. Analysis of Free-Text Answers

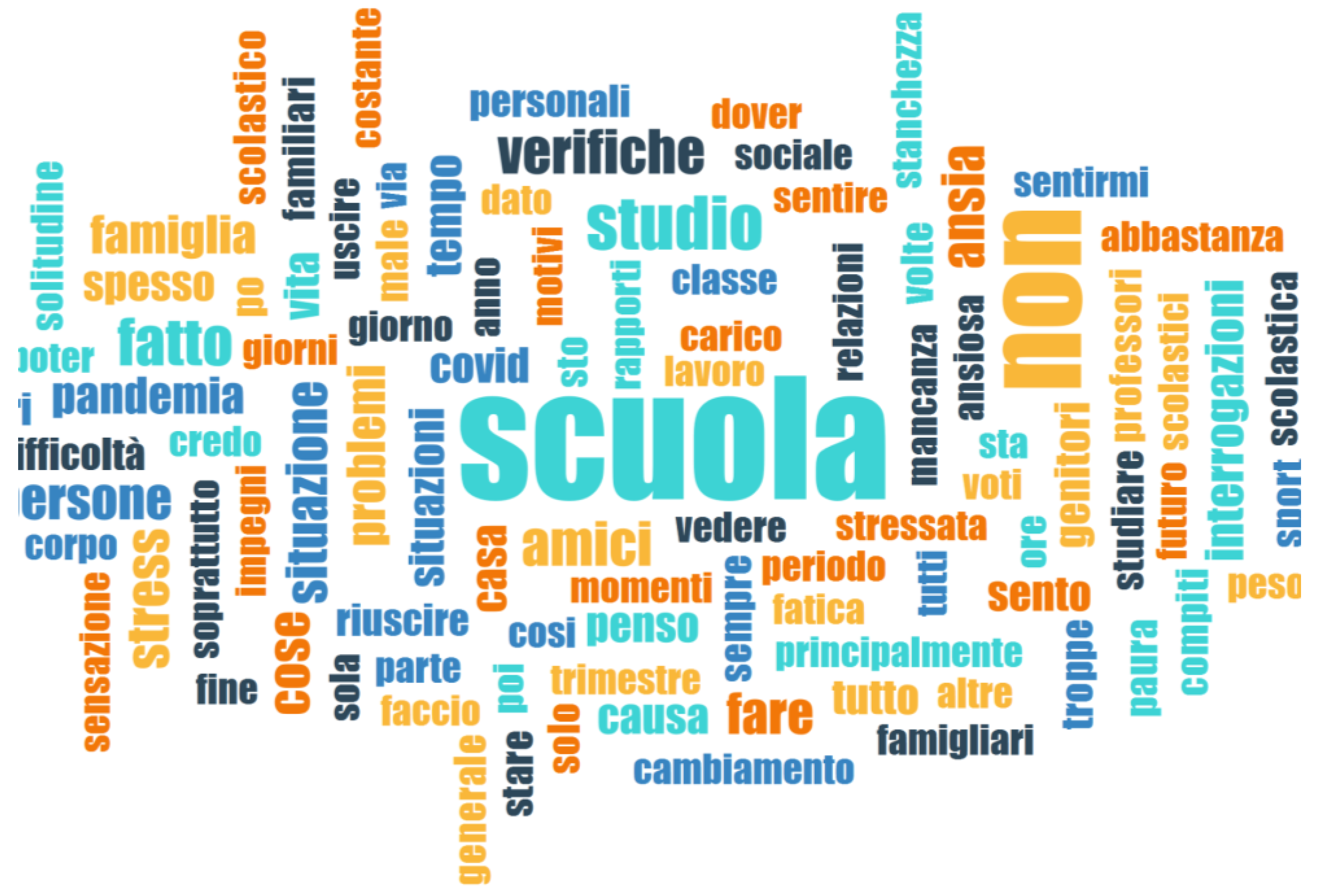

3.3.1. Lexical Analysis

3.3.2. Thematic Analysis

- School: school, study load, and distress caused by teachers, tests and marks were mentioned in 428 answers (57%).

- Interpersonal relationships: difficulties relating with classmates, friends, and/or family members were mentioned in 218 answers (29%).

- Negative emotional states: negative emotional states such as anxiety, fear of failure, or lack of motivation were mentioned in 107 answers (14%). Some of these answers (12% of the subset, 1.7% of the total) described profound psychological distress such as depression, eating disorders, panic attacks, self-harm, and suicidal ideation.

- Covid-19 pandemic: 85 answers (11%) mentioned the consequences of the restrictions and/or fears of catching Covid.

- Overall negative, but otherwise unspecified, emotional state: 68 answers (9%) described a general, but otherwise unspecified, feeling of distress, and/or the writer’s inability to identify one or more specific cause/s for distress.

- Feelings of isolation and loneliness: were mentioned in 43 answers (6%).

-

Other: this category comprises 71 answers (9%) where participants mentioned other, less frequent causes for distress, such as:

- concerns for one’s physical appearance and/or food behaviors, mentioned in 22 answers (3%);

- distress caused by sports activities and training, mentioned in 16 answers (2%);

- distress caused by overuse of digital devices and/or social media, mentioned in 13 answers (2%);

- tiredness and/or poor sleep quality, mentioned in 9 answers (1%);

- dissatisfaction with one or more personality traits, mentioned in 5 answers (0,7%);

- dissatisfaction with one’s job and/or economic situation, mentioned in 4 answers (0,5%).

3.3.3. Examples from the Corpus

- School makes me feel anxious. I feel as if I couldn’t face all the pressure that is exerted on me by all the things I have to do and the expectations. (Girl, 14 years old)

- I think the main causes have been: school activities and the pressure exerted on me by my parents due to school. (Girl, 15 years old)

- Accumulation of written/oral tests because of the end of the term. I felt the pressure of doing well at school and having not to disappoint expectations. (Girl, 18 years old)

- The overload of homework and the teachers’ lack of understanding of the fact that we are coming out of a difficult period. They increase homework and punish more often, they are more frustrated than before!!! (Boy, 15 years old)

- School has recently made me feel very anxious because of tests and some teachers who don’t care about their students. (Boy, 15 years old)

- Because of covid, distance learning, studying increased considerably. So I was tired at the end of the day because I was studying too much and had too much homework. I no longer had time for myself, to have fun, etc … I used to spend hours and hours in front of the computer every day at all times. (Girl, 17 years old)

- The return to in-presence school has upset me a lot, I cannot keep up with the lessons, focus and study (Girl, 17 years old)

- I think school has made me feel depressed and changed me for the worse because I don’t feel inspired to do anything anymore. (Boy, 14 years old)

- Too much study, the overlapping written and oral tests. My mind was shattered and my body felt the consequences. (Girl, 15 years old)

- I had problems at school: I suffer from panic attacks and anxiety and when I have too many things to do I get anxious. I have attempted suicide twice in twenty days taking an exaggerated number of pills, even ending up in hospital. I felt overburdened with school and full of responsibilities, also due to the fact that I am a senior in high school. (Girl, 18 years old)

- Arguments with my classmates, they have “insulted”, excluded, isolated me, and they have turned most of the class against me. (Boy, 14 years old)

- Not feeling understood, being less energetic, feeling a void inside due to disappointments caused by people who were once important in my life and consequently not being able to trust people anymore. (Girl, 15 years old)

- The causes are my oppressive parents who would not accept my homosexuality, given that they already do not accept me. (Girl, 13 years old)

- They keep telling me the same things over and over, it’s tiring. My parents should talk about something else besides school, otherwise my self-esteem keeps getting lower and lower. (Boy, 15 years old)

- The lack of relationships has caused a loss in my ability to relate with others, causing a feeling of inadequacy when I am in a group. (Girl, 15 years old)

- There are many things that make me feel anxious, I am constantly feeling strained. (Girl, 18 years old)

- Depression and anxiety which have caused difficult situations such as self-harm. (Girl, 15 years old)

- Lately I have been losing the desire to go out, I prefer to stay in my comfort zone, in my room. I no longer find stimuli to go out and I am not interested in taking care of myself. […] I have also noticed that I have been more sensitive and irritable since the pandemic started. In the initial period of this tragedy I unfortunately started to feel very lonely and I found relief in self-harm, which I have, sadly, recently resumed. (Girl, 13 years old)

- My mind during this long period coinciding with the beginning of the pandemic until today has undergone a radical change, and today the situation is certainly very negative compared to before, due to the emergence of countless situations of discouragement, panic attacks and moments of pressure or depression, which have had a great emotional impact. Certainly all this is also linked with the emergence of problems and obsessive behavior towards my body, which has totally changed due to a loss of more than 30 kg, both in terms of training and above all nutrition, which today have led me to have to follow a psychological and nutritional counseling course. (Boy, 17 years old)

- I started thinking about life, how it could end at any moment. I started to think that I am not enough for others (but it’s me who thinks so). I am also frightened of myself because I sometimes think about the option of suicide and I am terrified just thinking that I might do something that could make other people suffer. (Girl, 15 years old)

- The fact that I stayed at home with my parents and my sister and I have not seen my friends for a long time. (Girl, 15 years old)

- I think the fact that I stayed at home and never went out, that I no longer had contact with people and did not play the sport I loved. (Boy, 15 years old)

- During the pandemic I had a lot of time to think and to spend time with my very toxic family, and this has harmed me a lot, and several times I have thought about ending it, I was and still am mentally shattered but no one notices it. (Girl, 14 years old)

- A general dissatisfaction with several aspects of life which I am struggling with and which make me unable to focus on other aspects on which I should be more serene. (Boy, 18 years old)

- Well I don’t know.. I don’t know there’s no valid reason.. (Girl, 15 years old)

- Inexplicable anxiety, for I don’t know what! (Girl, 17 years old)

- The fact that I felt extremely lonely, I was looking for help but no one could help me, neither within the family nor outside. (Boy, 13 years old)

- Probably this difficult situation we find ourselves in, digital devices which are addictive. This in my case heavily affects sleep, it’s difficult to fall asleep and I often wake up in the middle of the night. (Girl, 14 years old)

- I waste too much time with my smartphone and I can’t restrict its use, I find it difficult to organize myself with my studies both because of the smartphone and because I struggle to focus, I am aware that I’m wasting my time but I can’t change this situation. (Girl, 15 years old)

- Problems with my body and food. (Girl, 16 years old)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO International Health Regulations Emergency Committee for the COVID-19 Outbreak. Epidemiol. Health 2020, 42, e2020013. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): STRATEGIC PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE PLAN, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/srp-04022020.pdf.

- Salzano, G.; Passanisi, S.; Pira, F.; Sorrenti, L.; La Monica, G.; Pajno, G.B.; Pecoraro, M.; Lombardo, F. Quarantine Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic from the Perspective of Adolescents: The Crucial Role of Technology. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cereda, D.; Manica, M.; Tirani, M.; Rovida, F.; Demicheli, V.; Ajelli, M.; Poletti, P.; Trentini, F.; Guzzetta, G.; Marziano, V.; et al. The Early Phase of the COVID-19 Epidemic in Lombardy, Italy. Epidemics 2021, 37, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Italian Prime Minister. Law Decree February 23rd 2020.

- Viner, R.M.; Ozer, E.M.; Denny, S.; Marmot, M.; Resnick, M.; Fatusi, A.; Currie, C. Adolescence and the Social Determinants of Health. The Lancet 2012, 379, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samji, H.; Wu, J.; Ladak, A.; Vossen, C.; Stewart, E.; Dove, N.; Long, D.; Snell, G. Review: Mental Health Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Youth – a Systematic Review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aknin, L.B.; De Neve, J.E.; Dunn, E.W. Mental Health During the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review and Recommendations for Moving Forward. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 17, 915–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The Age of Adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardin, A.P.; Hackell, J.M.; Simon, G.R.; Boudreau, A.D.A.; Baker, C.N.; Barden, G.A.; Meade, K.E.; Moore, S.B.; Richerson, J.; COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE AND AMBULATORY MEDICINE. Age Limit of Pediatrics. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20172151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussong, A.M.; Benner, A.D.; Erdem, G.; Lansford, J.E.; Makila, L.M.; Petrie, R.C.; The SRA COVID-19 Response Team. Adolescence Amid a Pandemic: Short- and Long-Term Implications. J. Res. Adolesc. 2021, 31, 820–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; Norton & Co.: Oxford, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Adolescents, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health.

- Ghafari, M.; Nadi, T.; Bahadivand-Chegini, S.; Doosti-Irani, A. Global Prevalence of Unmet Need for Mental Health Care among Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2022, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santomauro, D.F.; Mantilla Herrera, A.M.; Shadid, J.; Zheng, P.; Ashbaugh, C.; Pigott, D.M.; Abbafati, C.; Adolph, C.; Amlag, J.O.; Aravkin, A.Y.; et al. Global Prevalence and Burden of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in 204 Countries and Territories in 2020 Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. The Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine, N.; McArthur, B.A.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Zhu, J.; Madigan, S. Global Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrell, T.D.; Kim, S.; Mohadikar, K.; Jonas, C.; Ortiz, N.; Horberg, M.A. Family Structure and Adolescent Mental Health Service Utilization During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 73, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, G.; Apicella, M.; Iannoni, M.E.; Trasolini, M.; Andracchio, E.; Chieppa, F.; Averna, R.; Guidetti, C.; Maglio, G.; Reale, A.; et al. Urgent Psychiatric Consultations for Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors in Italian Adolescents during Different COVID-19 Pandemic Phases. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, D.-J.; Cho, H.; Yang, S. The Smartphone Addiction Scale: Development and Validation of a Short Version for Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F.; et al. Eating Habits and Lifestyle Changes during COVID-19 Lockdown: An Italian Survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Kuwahara, K. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Adolescents’ Lifestyle Behavior Larger than Expected. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 531–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, O.; Malorgio, E.; Doria, M.; Finotti, E.; Spruyt, K.; Melegari, M.G.; Villa, M.P.; Ferri, R. Changes in Sleep Patterns and Disturbances in Children and Adolescents in Italy during the Covid-19 Outbreak. Sleep Med. 2022, 91, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, V.; Wiedermann, C.J.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Piccoliori, G.; Plagg, B.; Mahlknecht, A.; Ausserhofer, D.; Engl, A.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents after the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Large Population-Based Survey in South Tyrol, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Devine, J.; Schlack, R.; Otto, C. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents in Germany. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, S.; Skogen, J.C.; Sandal, G.M.; Haug, E.; Bjørknes, R. Emerging Mental Health Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Presumably Resilient Youth -a 9-Month Follow-Up. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orban, E.; Li, L.Y.; Gilbert, M.; Napp, A.-K.; Kaman, A.; Topf, S.; Boecker, M.; Devine, J.; Reiß, F.; Wendel, F.; et al. Mental Health and Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1275917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourghazi, F.; Eslami, M.; Ehsani, A.; Ejtahed, H.-S.; Qorbani, M. Eating Habits of Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Era: A Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1004953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanini, B.; Covolo, L.; Marconi, S.; Marullo, M.; Viola, G.C.V.; Gelatti, U.; Maroldi, R.; Latronico, N.; Castellano, M. Change in Eating Habits after 2 Years of Pandemic Restrictions among Adolescents Living in a City in Northern Italy: Results of the COALESCENT Observational Study (Change amOng ItAlian adoLESCENTs). BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2024, e000817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerniglia, L.; Cimino, S. Eating Disorders and Internalizing/Externalizing Symptoms in Adolescents before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 2023, 42, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shawon, M.S.R.; Rouf, R.R.; Jahan, E.; Hossain, F.B.; Mahmood, S.; Gupta, R.D.; Islam, M.I.; Al Kibria, G.M.; Islam, S. The Burden of Psychological Distress and Unhealthy Dietary Behaviours among 222,401 School-Going Adolescents from 61 Countries. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marconi, S.; Covolo, L.; Marullo, M.; Zanini, B.; Viola, G.C.V.; Gelatti, U.; Maroldi, R.; Latronico, N.; Castellano, M. Cooking Skills, Eating Habits and Nutrition Knowledge among Italian Adolescents during COVID-19 Pandemic: Sub-Analysis from the Online Survey COALESCENT (Change amOng ItAlian adoLESCENTs). Nutrients 2023, 15, 4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pasquale, C.; Sciacca, F.; Hichy, Z. Validation of the Italian Version of the Dissociative Experience Scale for Adolescents and Young Adults. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2016, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Vedova, A.M.; Covolo, L.; Muscatelli, M.; Loscalzo, Y.; Giannini, M.; Gelatti, U. Psychological Distress and Problematic Smartphone Use: Two Faces of the Same Coin? Findings from a Survey on Young Italian Adults. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 132, 107243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthey, S.; Valenti, B.; Souter, K.; Ross-Hamid, C. Comparison of Four Self-Report Measures and a Generic Mood Question to Screen for Anxiety during Pregnancy in English-Speaking Women. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 148, (2–3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthey, S.; Souter, K.; Valenti, B.; Ross-Hamid, C. Validation of the MGMQ in Screening for Emotional Difficulties in Women during Pregnancy. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 256, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthey, S.; Della Vedova, A.M. A Comparison of Two Measures to Screen for Emotional Health Difficulties during Pregnancy. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2018, 36, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.M.; De Boer, M.R.; Van Der Windt, D.A.W.M.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; De Vet, H.C.W. Quality Criteria Were Proposed for Measurement Properties of Health Status Questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, M.M.; Capone, L.; Rogantini, C.; Orlandi, M.; Ballante, E.; Borgatti, R. COVID-19-related Psychiatric Impact on Italian Adolescent Population: A Cross-sectional Cohort Study. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensi, M.M.; Iacopelli, M.; Orlandi, M.; Capone, L.; Rogantini, C.; Vecchio, A.; Casini, E.; Borgatti, R. Psychiatric Symptoms and Emotional Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Italian Adolescents during the Third Lockdown: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth; Bonnie, R.J., Backes, E.P., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, M. The Relationship between Eating Habits and Mental Development in Adolescents. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2023, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.E.; Ethier, K.A.; Hertz, M.; DeGue, S.; Le, V.D.; Thornton, J.; Lim, C.; Dittus, P.J.; Geda, S. Mental Health, Suicidality, and Connectedness Among High School Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic — Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Suppl. 2022, 71, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montomoli, C.; Costantino, M.A.; Filosa, A.; Franchi, M.; Borgatti, R.; Cantarutti, A.; Fazzi, E.; Galli, J.; Ghisoni, R.; Leoni, O.; Limosani, I.; Loi, E.; Mensi, M.; Poli, V.; Sacchi, P.; Villani, S.; Corrao, G. Neurosviluppo, salute mentale e benessere psicologico di bambini e adolescenti in Lombardia 2015-2022.

- Ionio, C.; Ciuffo, G.; Villa, F.; Landoni, M.; Sacchi, M.; Rizzi, D. Adolescents in the Covid Net: What Impact on Their Mental Health? J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2024, 17, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.M. What Makes Adolescents Psychologically Distressed? Life Events as Risk Factors for Depression and Suicide. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loscalzo, Y.; Giannini, M. Studyholism and Study Engagement in Adolescence: The Role of Social Anxiety and Interpretation Bias as Antecedents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steare, T.; Gutiérrez Muñoz, C.; Sullivan, A.; Lewis, G. The Association between Academic Pressure and Adolescent Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambelli, R.; Cimino, S.; Marzilli, E.; Ballarotto, G.; Cerniglia, L. Late Adolescents’ Attachment to Parents and Peers and Psychological Distress Resulting from COVID-19. A Study on the Mediation Role of Alexithymia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 10649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzilli, E.; Cerniglia, L.; Tambelli, R.; Trombini, E.; De Pascalis, L.; Babore, A.; Trumello, C.; Cimino, S. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impact on Families’ Mental Health: The Role Played by Parenting Stress, Parents’ Past Trauma, and Resilience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 11450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner-Seidler, A.; Perry, Y.; Calear, A.L.; Newby, J.M.; Christensen, H. School-Based Depression and Anxiety Prevention Programs for Young People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 51, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, A.J.; Hoffmann, M.S.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Ziebold, C.; De Miranda, C.T.; Mcdaid, D.; Tomasi, C.; Ribeiro, W.S. Efficacy of School-Based Interventions for Mental Health Problems in Children and Adolescents in Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1012257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therriault, D.; Lane, J.; Houle, A.A.; Dupuis, A.; Gosselin, P.; Thibault, I.; Dionne, P.; Morin, P.; Dufour, M. Effects of the HORS-PISTE Universal Anxiety Prevention Program Measured According to Initial Level of Student Problems. Psychol. Sch. 2022, 60, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, U.; Salazar De Pablo, G.; Franco, M.; Moreno, C.; Parellada, M.; Arango, C.; Fusar-Poli, P. The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Child and Adolescent Mental Health: Systematic Review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 1151–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Presence of distress | P value | AdjOR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| Age (Years) | N (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| 13-15 | 369 (44.8) | Reference | ||

| 16-18 | 455 (56.2) | 1.64 (1.29-2.08) | <0.0001 | |

| 19-21 | 24 (45.3) | 1.04 (0.53-2.04) | ns | |

| Gender | <0.0001 | |||

| Male | 251 (31.9) | Reference | ||

| Female | 567 (67.0) | 2.27 (1.77-2.90) | <0.0001 | |

| Not specified | 30 (55.6) | 1.34 (0.68-2.63) | ns | |

| Type of School | 0.019 | |||

| State-funded | 632 (48.7) | Reference | ||

| Private | 216 (55.5) | 1.15 (0.79-1.66) | ns | |

| Parents’ education (n=1,470) | 0.053 | |||

| High school degree or less | 427 (48.8) | Reference | ||

| University degree1 | 321 (54.0) | 1.17 (0.86-1.58) | ns | |

| Change in eating habits compared to pre-pandemic period (food amount) | <0.0001 | |||

| I eat as before | 200 (35.1) | Reference | ||

| I eat more | 224 (51.5) | 1.09 (0.79-1.51) | ns | |

| I eat less | 272 (69.7) | 1.90 (1.35-2.69) | <0.0001) | |

| I don’t know | 152 (52.2) | 1.24 (0.88-1.76) | ns | |

| Change in eating habits compared to pre-pandemic period (food quality) | <0.0001 | |||

| They did not change | 218 (33.9) | Reference | ||

| They are healthier | 219 (50.6) | 1.21 (0.89-1.65) | ns | |

| They are less healthy | 129 (66.2) | 1.63 (1.07-2.49) | 0.024 | |

| They changed but I don’t know how | 282 (68.1) | 2.00 (1.45-2.78) | <0.0001 | |

| Weight change compared to pre-pandemic period | <0.0001 | |||

| My weight is the same | 270 (42.7) | Reference | ||

| My weight has increased | 227 (49.2) | 1.00 (0.69-1.47) | ns | |

| My weight has decreased | 236 (65.0) | 1.49 (0.97-2.29) | ns | |

| I don’t know/I prefer not to answer | 115 (50.2) | 0.91 (0.54-1.53) | ns | |

| Comfort food consumption | <0.0001 | |||

| No/I don’t know | 399 (37.9) | Reference | ||

| Yes, more than before the pandemic | 203 (73.0) | 1.50 (1.05-2.14) | 0.025 | |

| Yes, less than before the pandemic | 65 (70.7) | 1.88 (1.11-3.18) | 0.019 | |

| Yes, both before and during the pandemic | 181(68.6) | 2.02 (1.44-2.83) | <0.0001 | |

| Change in moderate physical activity compared to pre-pandemic period | <0.0001 | |||

| Unchanged | 339 (45.4) | Reference | ||

| Decreased | 201 (61.5) | 1.44 (0.98-2.11) | ns | |

| Increased | 308 (50.2) | 1.17 (0.86-1.60) | ns | |

| Physical activity2 | 0.05 | |||

| Active | 226 (46.6) | Reference | ||

| Inactive | 622 (51.8) | 0.89 (0.64-1.24) | ns | |

| Engagement in a sport club before the pandemic3 | 0.026 | |||

| Yes No |

554 (48.4) 294 (54.2) |

|||

| Maintenance of commitment with the sport club4 | 0.049 | |||

| Yes No |

290 (45.8) 264 (51.7) |

Reference 0.78 (0.59-1.04) |

ns | |

| Sleep duration | <0.0001 | |||

| > 8 hours | 254 (40.4) | Reference | ||

| < 8 hours | 594 (56.2) | 1.45 (1.14-1.85) | 0.003 | |

| Change in sleep quality compared to pre-pandemic period | <0.0001 | |||

| Unchanged | 369 (40.6) | Reference | ||

| Improved | 135 (46.6) | 0.89 (0.60-1.33) | ns | |

| Worsened | 344 (70.6) | 1.23 (0.84-1.79) | ns | |

| Smartphone addiction (mean ± SD) | 33.7±9.1 vs 29.9±8.95 | <0.0001 | 1.02 (1.0-1.03) | 0.007 |

| Increased anxiety perception compared to pre-pandemic period | <0.0001 | |||

| No/I don’t know/I prefer not to answer Yes |

284 (30.4) 564 (74.8) |

Reference 3.37 (2.88-4.68) |

<0.0001 | |

| Increased fear of getting sick compared to pre-pandemic period | 0.001 | |||

| No/I don’t know/I prefer not to answer | 216 (58.2) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 632 (48.1) | 0.95 (0.66 -1.37) | ns | |

| Increased need of health professional support compared to pre-pandemic period | <0.0001 | |||

| No/I prefer not to answer | 649 (45.5) | Reference | ||

| Yes | 199 (76.8) | 1.84 (1.29-2.62) | 0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).