1. Introduction

In Romania, balneal healthcare involves therapeutic treatments conducted in thermal stations/resorts using natural or artificially produced therapeutic factors, alongside diet, medication, psychotherapy, and health education. Traditionally, treatment courses lasted 18 to 21 days, but modern practices have reduced this to 12 days, with 10 days allocated to balneal treatment.

Mud is a complex mixture of organic and inorganic substances with unique biophysical properties and biochemical compositions, making it a distinct natural therapeutic agent. Techirghiol Lake, situated on Romania’s Black Sea coast, is renowned for its hypersaline water and deposits of organic mud. The lake’s water contains high concentrations of salts (66-86 g/l), primarily sodium chloride and sulfates. The mud from its deposits is rich in organic substances (9.6 g/l), including waxes, resins, fats, amino acids, and humic acids, with a high water content (71.24%) and abundant minerals (28.73 g/l), such as calcium, manganese, sodium, potassium, iodides, bromides, and sulfur compounds.

Techirghiol mud exhibits high thermal capacity and low thermal conductivity, capable of storing substantial heat without causing harm at temperatures up to 42°C. The optimal thermal neutrality temperature is 38°C, which does not require circulatory adaptation. Outdoor application of mud is recommended between July and early September, when air temperatures exceed 24°C and the lake’s water temperature surpasses 20°C. Daily temperature measurements and application protocols are displayed at the solarium.

Balneotherapy utilizes natural therapeutic factors (mineral/thermal waters, mud, clay, peat) in structured balneal courses as a form of physical therapy. Topical application of mud and natural mineral water (cold, warm, hot) induces temperature modifications that lead to physiological changes in the dermis and muscles to maintain thermal homeostasis.

The skin responds to biophysical stimuli such as temperature and pressure, primarily through peripheral blood circulation. Biochemical compounds in mud, including hydrogen sulfide, ions, humic acids, and amino acids, penetrate the skin and disseminate within bodily fluids and organs. Studies have linked the therapeutic effects of balneotherapy to these inorganic components.

The dermis and muscles are highly vascularized, facilitating blood transport, distribution, exchange with tissues, and blood storage. Dermis vascularization exceeds the skin’s biological needs and plays a crucial role in thermoregulation.

Direct application of topical heat on the skin increases tissue temperature and local blood flow. For instance, studies have shown that applying a heating pad at 40ºC to the lower back region increased deep muscle tissue temperature by 5ºC, 3.5ºC, and 2ºC at depths of 19 mm, 28 mm, and 38 mm below the skin surface, respectively [

5]. Similarly, applying heat to the knees increased popliteal artery blood flow by 29%, 94%, and 200% with heating pad temperatures of 38ºC, 40ºC, and 43ºC, respectively [

6]. There is a well-established linear relationship between local temperature increases (skin and muscle) and corresponding increases in local blood flow [

7]. Animal model studies under experimental conditions have demonstrated capillary growth and increased blood vessel density in response to increased blood flow [

8,

9].

This study aims to investigate the response of skin and muscle tissue to heat stimulation (hyperthermal, thermal neutral, thermal contrast) using hypersaline water and mud from Techirghiol Lake under real-life conditions, following established therapeutic protocols. Statistical analysis will be employed to analyze the data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

- -

natural therapeutic factors specific for Techirghiol ecosystem: mud from the bottom of the lake and hypersaline water of Techirghiol Lake, as they are described in balneal law [

10] ;

- -

facilities for treatment of Techirghiol Balneal and Rehabilitation Sanatorium: bathes tubs, beds, swimming pool, solarium (beach in front side of lake and its` facilities) as they are described in methodological norms [

11] and applied according to therapeutic protocol;

- -

laboratory reagents, fixators, solvents, specific dyestuffs, microtome, research microscope, equipped with automatic expometer and video camera, soft of image analysis LUCIA© G;

- -

IBM computer, SPSS statistics software version 23,

- -

facilities of Emergency Unit from Constanta University Emergency Clinical Hospital.

2.2. Development of the Study

Therapeutic Intervention:

According to the therapeutic protocol, mud therapy at the Techirghiol Balneal and Rehabilitation Sanatorium is applied as follows:

- ⮚

Cold Mud Ointment: Applied outdoors during the summer season, combined with heliotherapy and immersion in the lake’s water.

- ⮚

Mud Pack: Applied indoors year-round, using hyperthermal mud (42°C) for 20-30 minutes.

- ⮚

Mud Bath: Applied indoors year-round, using thermally neutral mud (38°C) for 20-30 minutes, alternating with thermally neutral hypersaline water baths (37°C) as part of a ten-day balneal course, within a twelve-day stay at the thermal station.

Patients underwent clinical evaluation and biological investigation before and after the treatment. Heart rate and blood pressure were monitored throughout the course, in accordance with the sanatorium’s therapeutic protocol.

The study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013). The project received legal approval from the Bioethics Committee of Techirghiol Balneal and Rehabilitation Sanatorium. Participants were informed of the risks and discomforts associated with the biopsy procedure and provided written informed consent. They also agreed to the processing of personal data and the publication of the study results while maintaining confidentiality.

Admission to the balneal course is regulated by a Framework Contract with the National Insurance House, which reimburses 65% of the hospitalization costs per day [

12]. Admission requires a referral and a medical recommendation detailing the primary diagnosis and any comorbidities (secondary diagnosis).

Participants:

Thirty-five inpatients participated in this study, divided into groups based on the type of mud application: ten patients for each type of mud application (cold mud ointment, mud pack, mud bath), and five patients in the control group who received thermally neutral tap water baths.

Inclusion Criteria:

Participants included in the study were inpatients who met the criteria for admission to the balneal course, hospitalized for chronic rheumatologic conditions (osteoarthritis) and post-traumatic sequelae. They were prescribed whole-body balneotherapy with hypersaline water and mud.

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

Cardiovascular conditions (recent myocardial infarction or cardiovascular surgery), heart failure, uncontrolled hypertension, vasodilatory medication.

Skin conditions (psoriasis, eczema).

Chronic inflammatory conditions (rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, lupus).

Neurological conditions (multiple sclerosis, hemiparesis following a recent stroke).

Muscular conditions (Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, Juvenile Dermatomyositis).

Chronic organ failure (kidney, lung).

Clinical and/or biological signs of inflammation.

Cropping, samples numbering and fixation.

Biopsy Collection:

Biopsies were collected from the belly of the deltoid muscle 24 hours after the completion of the balneal cure. A surgeon performed the procedure at the Emergency Unit of Constanța University Clinical Hospital, adhering to all requirements for minor surgical interventions. The biopsies were taken through a perpendicular incision on the skin, using contact anesthesia (spray). The incision was closed with a stitch and covered with a compress. The skin was first incised up to the muscle fascia, followed by the collection of the muscle fragment. The dimensions of the tissue samples were approximately 1.5 cm x 0.5 cm x 0.5 cm.

Immediately after collection, the tissue fragments were placed in glass test tubes containing fixative solution. The volume ratio of the tissue to the fixative solution was maintained at 1:10 to 1:15 to prevent tissue alteration. Each test tube was labeled and indexed according to the type of treatment and the patient number.

Processing the Assays for the Histological Study:

For microtome sectioning, the samples were first fixed in aldehydes, then dehydrated in ethanol, clarified with xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin blocks were sectioned using a microtome, and the sections were transferred and adhered to glass slides. The serial sections were stained with routine (hematoxylin-eosin) and specific stains (Masson’s trichrome, GS trichrome) [

13]. The stained sections were examined using a Nikon E–600 microscope equipped with a Sony video camera.

For histometric measurements, a 40x lens was used, calibrated with a Carl-Zeiss Jena standard slide. From the collection of slides for each patient, one slide was randomly selected, and 100 microscopic fields were analyzed in a zigzag pattern, similar to the method used for a leukogram.

Statistical Analysis:

The statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 23. Tests for Normality: Nonparametric tests were employed for comparisons between categories of the Group variable when the numerical variables did not meet the condition of a normal distribution (p < 0.05, Shapiro-Wilk Test).

Hypotheses Testing: Kruskal-Wallis tests and the Median test were used for hypotheses testing. The significance level was set at α = 0.05 and adjusted to α’ = 0.0125 (using Bonferroni correction for post hoc tests).

Comparative Analysis: The Mann-Whitney U Test was utilized to evaluate differences in the number of blood vessels between the dermis and muscle.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Participants in this study were patients admitted to the Techirghiol Balneal and Rehabilitation Sanatorium for a balneal course. Admission was conducted in accordance with the requirements of the admission protocol, which specifies indications and contraindications for the balneal course. The total number of participants was thirty-five, consisting of fifteen women and twenty men, aged between thirty-six and seventy-three years. Participants were distributed into three study groups of ten patients each and a control group of five patients (

Table 1).

The lowest age (36 years), lowest mean age (48.60 ± 8.8 years), and the broadest age range (36-64 years) were observed in the cold mud ointment group, which requires adequate peripheral circulation and thermoregulatory capacity.

The cold mud ointment therapy involves contrasting thermal treatments that demand strong adaptive cardiovascular capacity. This therapeutic procedure consists of six short alternations (10-15-20 minutes each) of temperature exposure, as follows:

- -

Heating under sun radiation,

- -

Cooling by immersion in the lake’s water,

- -

Heating under sun radiation,

- -

Cooling by applying cold mud,

- -

Heating under sun radiation, and

- -

Cooling by immersion in the lake to remove the mud.

This procedure requires rapid vasoconstriction and vasodilation, as well as quick adjustments in blood flow. Sweating is partially possible when the body is not covered by mud, reducing the need to dissipate heat.

Mud pack therapy is a hyperthermal treatment that covers the entire body, preventing sweating and demanding a significant adaptive response from the cardiovascular system. This therapy increases skin temperature, necessitating vasodilation and increased skin blood flow. Elderly individuals (over 70 years) with functional vulnerabilities may be contraindicated for hyperthermal and contrast thermotherapies due to the cardiovascular strain involved.

In the hyperthermal mud pack group, the mean age was 60.4 ± 7.5 years, with an age range of 49-69 years. Mud packs are applied indoors at a controlled temperature of 22-24°C, involving a single passive heat transfer from the mud (42°C) to the body (36-37°C) for 20-30 minutes. This treatment is suitable for patients with mild cardiovascular conditions.

In the mud bath group, the highest age (73 years) and highest mean age (60.9 ± 11.24 years) were recorded. Mud baths, applied at a thermally neutral temperature (38°C), are suitable for patients with cardiovascular conditions controlled by medication.

Cardiovascular status is a critical factor influencing overall homeostasis during the balneal course. Evaluations at admission are crucial, particularly in the summer season. Chronic heart failure patients are contraindicated for contrast therapy, as studies have shown that thermal tolerance to heat stress can be compromised by factors affecting stroke volume regulation, as well as neurological and hormonal factors influencing heart rate and vascular resistance. These impairments may limit thermoregulatory responses, increasing the risk of heat stroke and heat exhaustion during periods of elevated temperatures .

3.2. Histologic Aspect in Dermis and Muscle

The general histologic aspect of the dermis and muscle tissues was analyzed from the biopsies. Using histometric techniques, the number of angiogenesis vessels per microscopic field was quantified.

3.2.1. Dermis

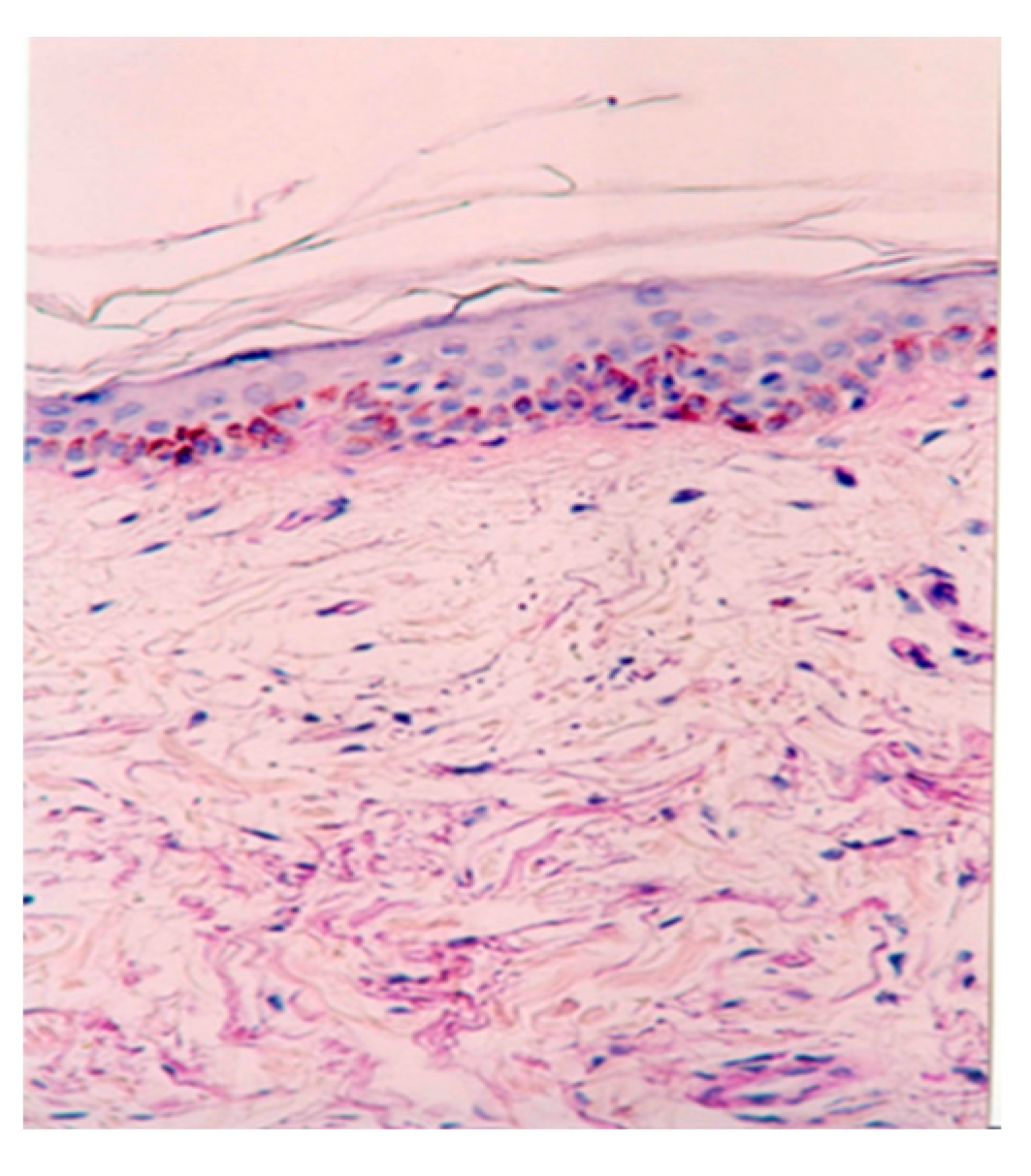

Routine (haematoxylin-eosin) and special (Mason’s trichrome) staining were performed on all biopsy samples, revealing normal histologic aspects across all slides. In the superficial dermis, a normal loose arrangement of connective tissue was observed (

Figure 1). Additionally, there was an increased number and calibre of open capillaries and angiogenesis vessels. Perivascular areas showed the presence of lymphocytes, plasma cells, mast cells, and pericytes.

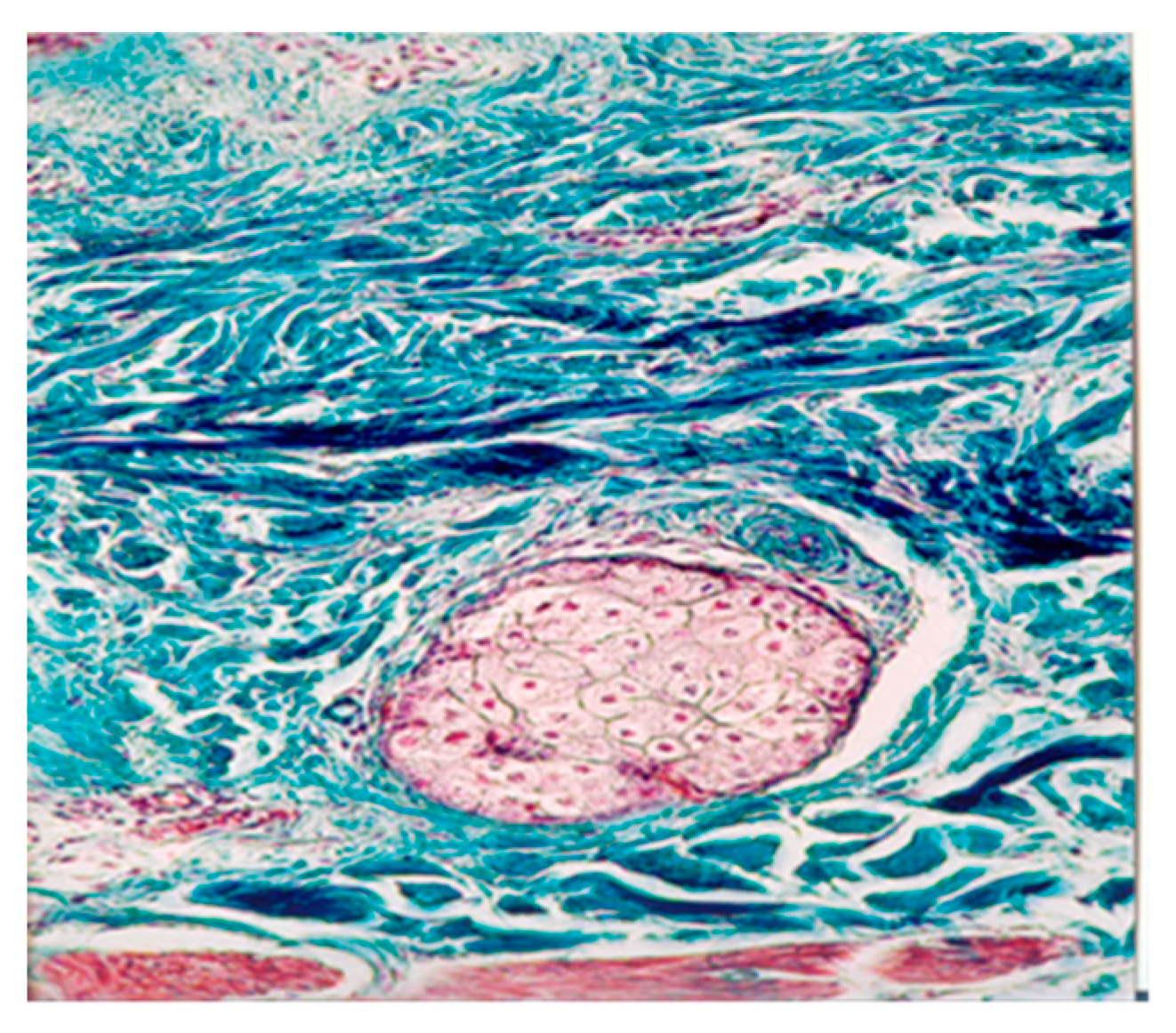

In the deep dermis, a semi-arranged dense connective tissue aspect was maintained (

Figure 2). Histological examination revealed an increased number and calibre of open capillaries and angiogenesis vessels. Additionally, perivascular areas showed the presence of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and pericytes. The pilo-sebaceous follicles, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands did not exhibit histological modifications.

The increased number and caliber of capillaries result from vasodilation and the opening of shunts, directly influenced by heat on the vessels and indirectly by the neuro-endocrine control system. Vasodilation and increased skin blood flow, along with sweating, play crucial roles in heat dissipation. However, application of mud over the entire skin surface (excluding the head) abolishes sweat evaporation and disrupts thermoregulation. During exposure to cold, skin vasoconstriction reduces heat loss from the body to prevent hypothermia. Any alteration in the control of skin blood flow can significantly impair the body’s ability to maintain normal temperature [

14].

Pericytes, located around capillaries, post-capillary venules, and angiogenesis vessels, perform crucial functions for vascular homeostasis, including the regulation of blood flow, vessel formation, and control of vascular growth and function. The molecular mechanisms underlying these processes have yet to be fully elucidated [

15]. In the analyzed biopsy samples, pericytes are observed participating in the occurrence, growth, and regulation of new vessels.

3.2.2. Muscle

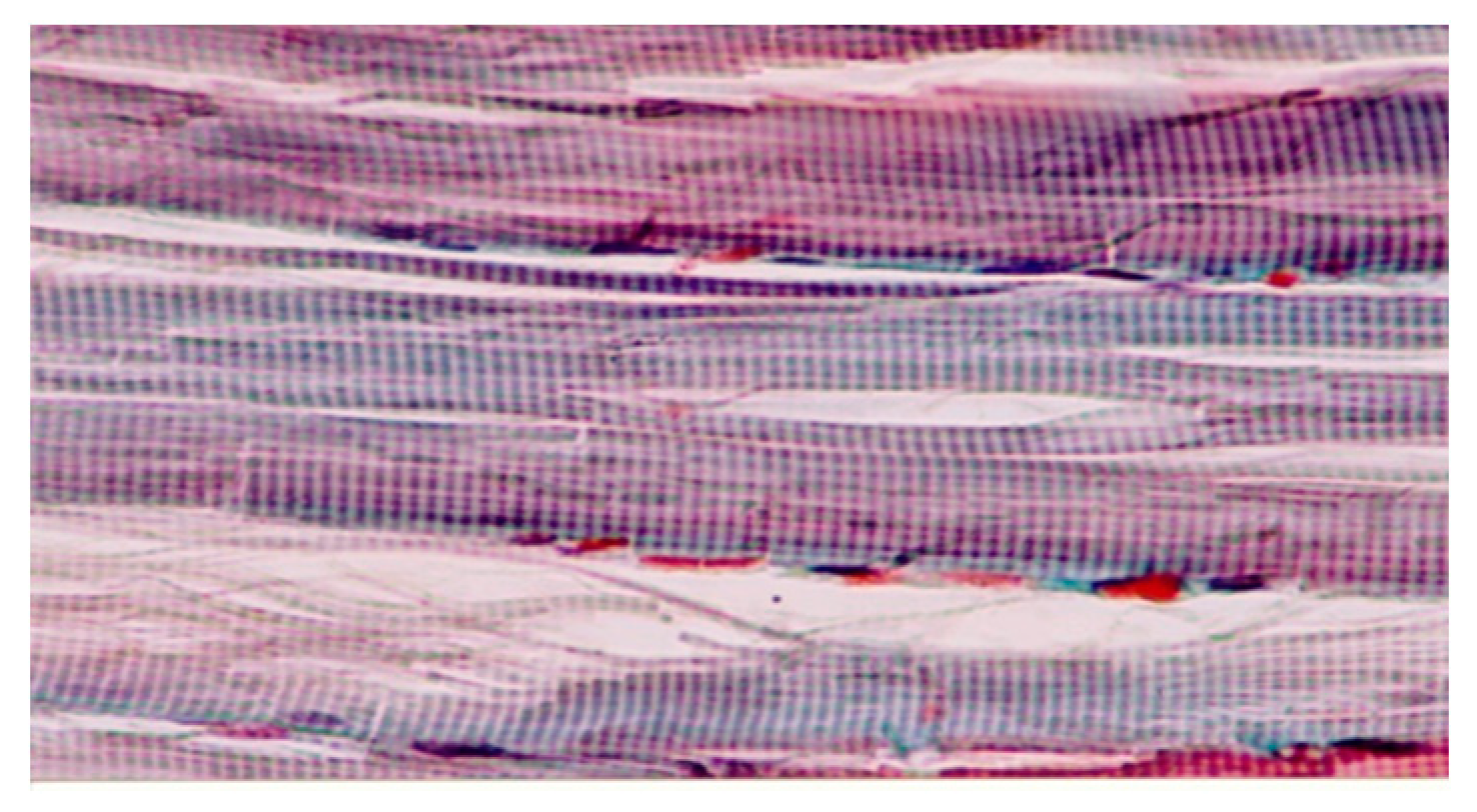

Microscopic examination of the muscle biopsy samples revealed a normal histologic structure of muscle tissue, characterized by a normal banding pattern and unaltered structure of the extracellular matrix (

Figure 4).

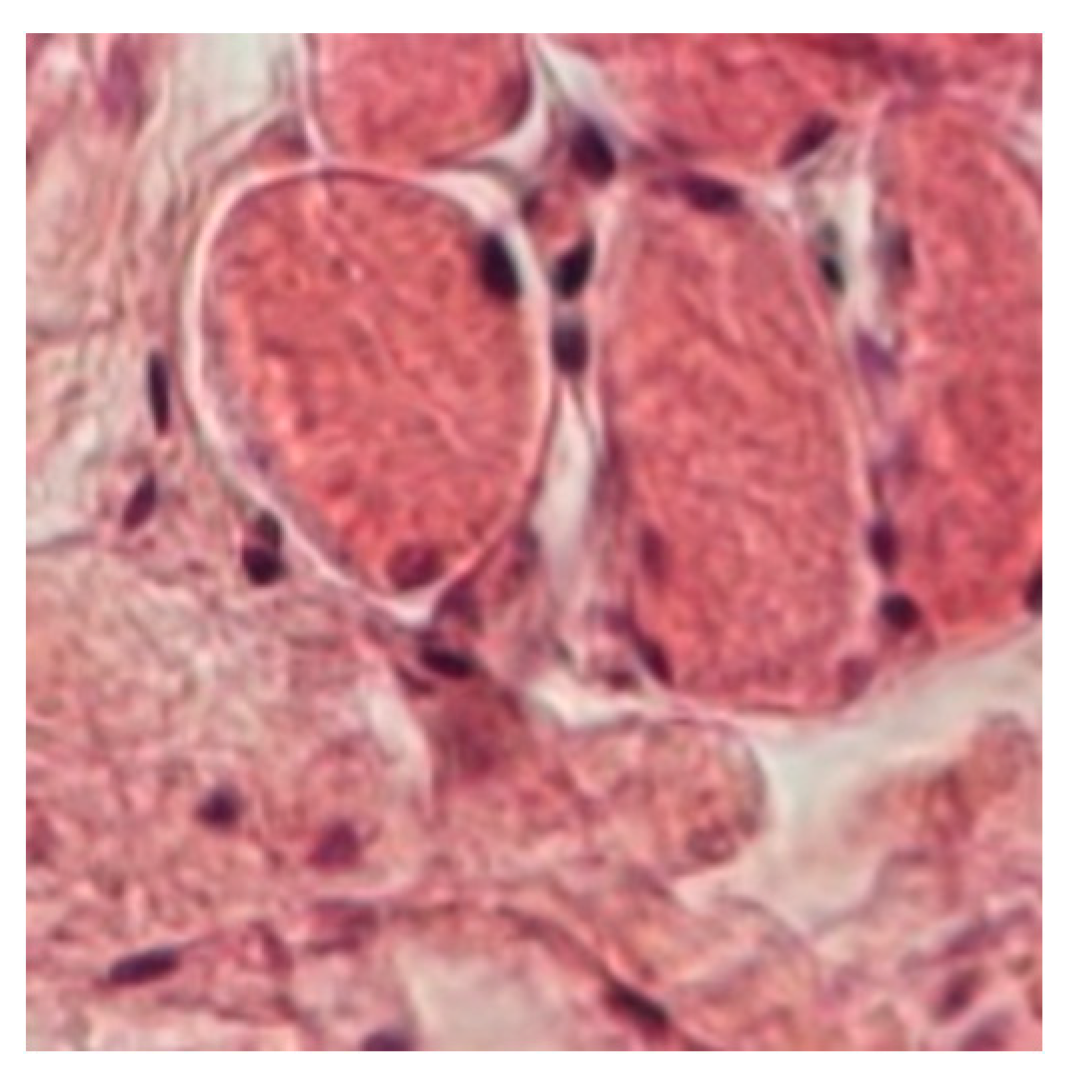

In the inter-fibrillary space of the muscle biopsy samples, an increased number and caliber of capillaries and angiogenesis vessels were observed, alongside connective tissue cells such as lymphocytes, other leukocytes, plasma cells, mast cells, fibroblasts, and pericytes (

Figure 5). Pericytes play essential roles as integral components of microvessel walls, contributing to metabolic support, signaling functions, and mechanical support for endothelial cells, roles that vary depending on tissue type and angiogenic stage.

Thermotherapy enhances local peripheral tissue perfusion through thermosensitive mechanisms that increase microvascular blood flow, correlating linearly with muscle temperature. This cascade includes increased muscle temperature, vasodilation, and enhanced oxygen consumption, which can trigger metabolically induced vasodilation [

7]. The regulation of skeletal muscle blood flow involves various compounds sourced from different cells, ensuring vital oxygen delivery to contracting skeletal muscle [

16].

Hydrogen sulfide, present in the biochemical composition of Techirghiol mud, has been recognized as a third gas signaling transmitter alongside nitric oxide and carbon monoxide, despite its historical classification as a toxic gas. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide modulates numerous physiological and pathological processes such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell apoptosis, crucial for vascular function [

17,

18].

Exogenous hydrogen sulfide from mineral/thermal waters and mud, including Techirghiol mud, can be absorbed through the skin and integrate into biological systems. Research in Romania has demonstrated that increased mud temperature enhances skin permeability to soluble substances from the liquid phase of mud, facilitating the passage of sulfur compounds into the skin [

19,

20]. Hydrogen sulfide has been shown to exert proangiogenic effects and improve regional blood flow [

21]. Recent studies highlight its vasculoprotective properties, influencing various cellular pathways involved in endothelial cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation within the vasculature. Despite its recognized benefits, the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying these pathways require further exploration [

22].

3.3. Number of Angiogenesis Vessels/Microscopic field

Histometric analysis was conducted to evaluate the number of angiogenesis vessels per microscopic field. The resulting values were tabulated and subjected to statistical analysis.

3.3.1. In the Dermis

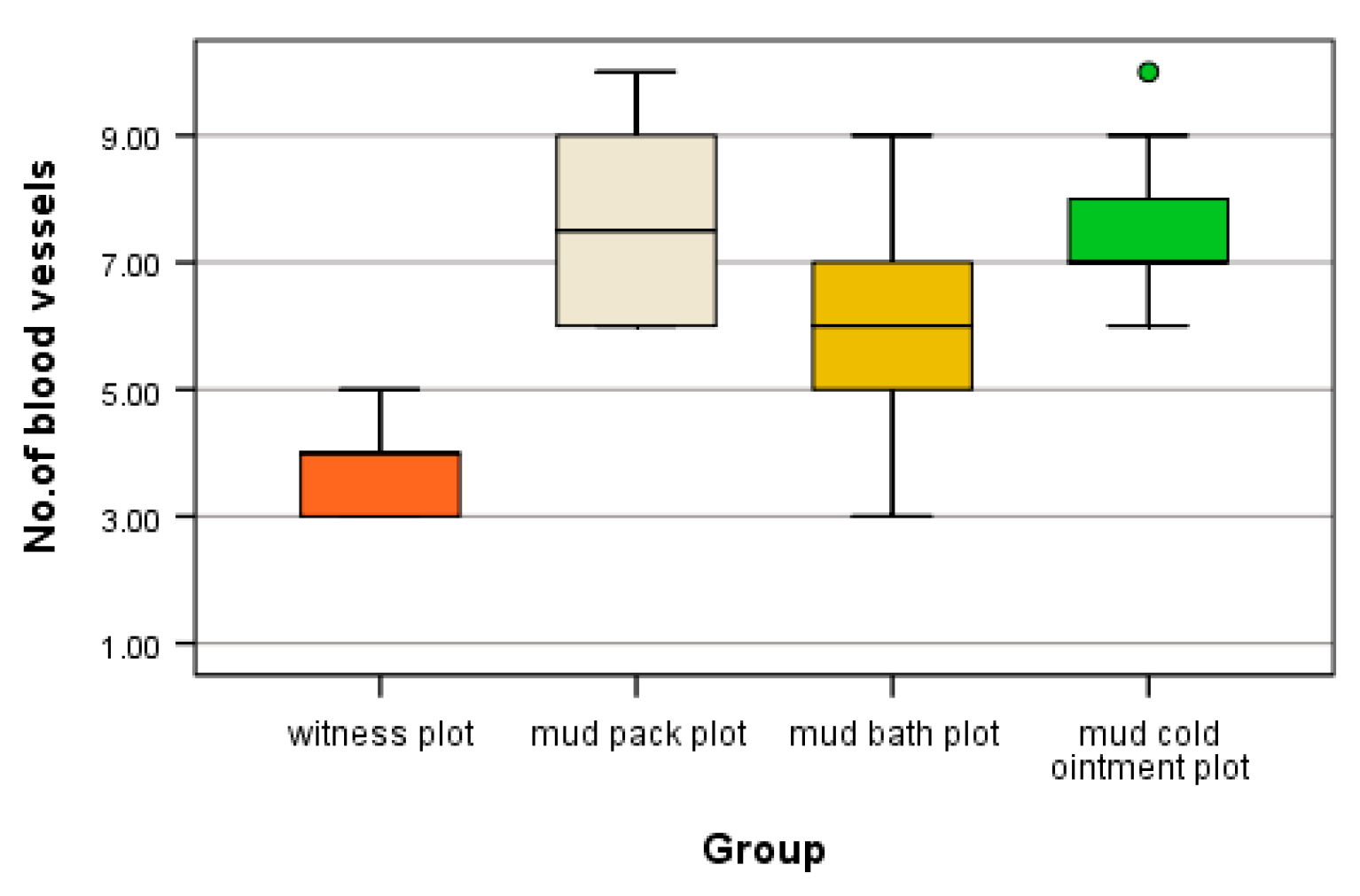

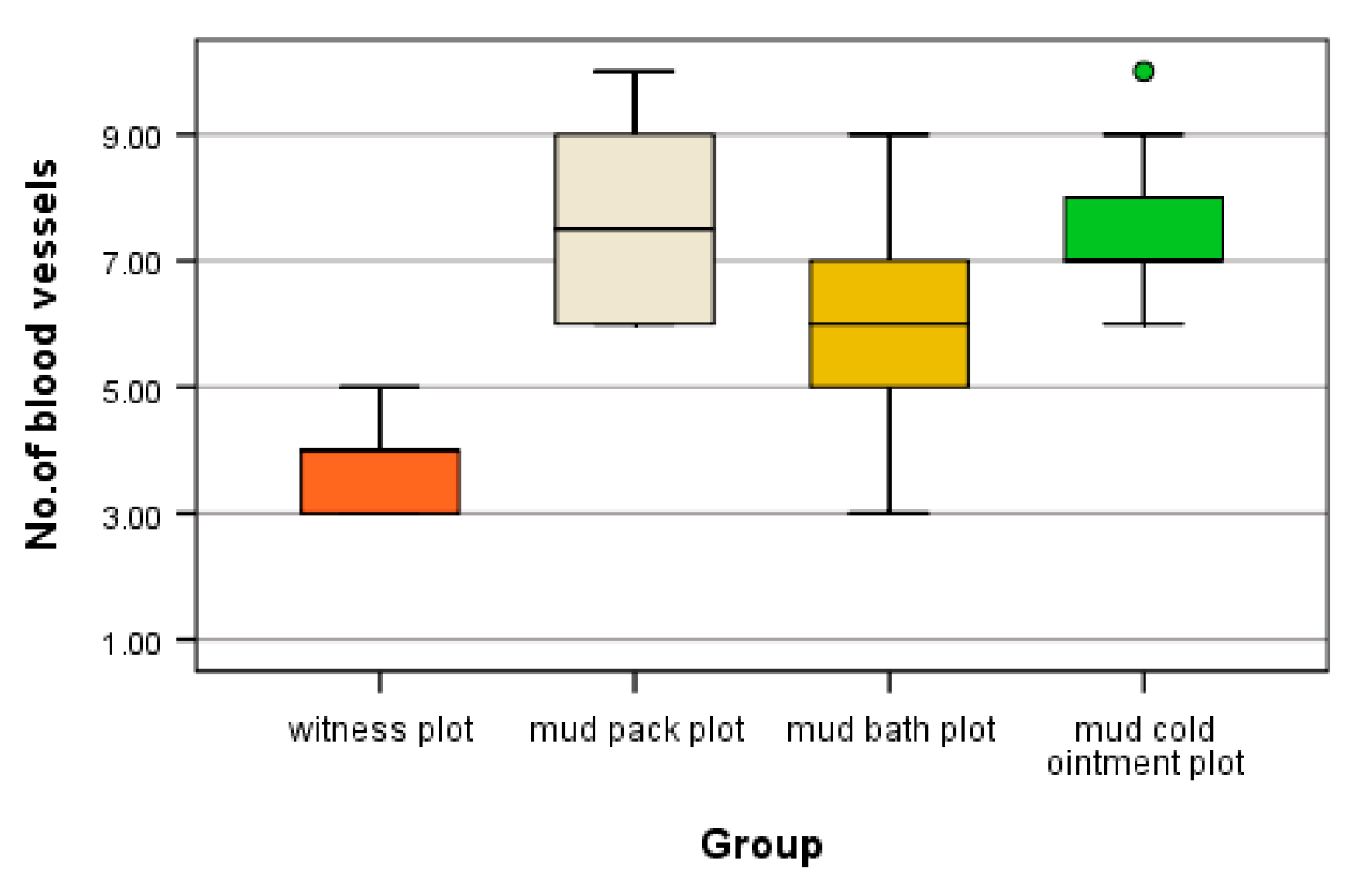

the count of angiogenesis vessels per microscopic field revealed varying values. The highest count, with ten angiogenesis vessels per microscopic field, was observed in the mud pack and cold mud ointment groups (

Table 2).

The blades from patients who received mud therapy exhibited a high mean and standard deviation of angiogenesis vessels: 7.60 ± 1.43 for the mud pack group, 7.50 ± 1.27 for the cold mud ointment group, 5.90 ± 1.79 for the mud bath group, and the lowest values of 4 ± 0.71 were observed in the witness plot (

Table 3).

Compared to the witness plot, the number of angiogenesis vessels differed significantly in all mud thermotherapy plots (H = 15.586, df = 3, p = 0.001 < α = 0.05, mean ranks: 4.60 for witness plot, 23.40 for mud pack plot, 14.20 for mud bath plot, and 23.10 for cold mud ointment plot).

Further statistical analysis revealed significant differences between the witness plot and the mud pack plot (padj = 0.004 < α = 0.05), as well as between the witness plot and the cold mud ointment plot (padj = 0.004 < α = 0.05). No statistically significant differences were found between the other categories (padj = Bonferroni-adjusted p value) (

Figure 6).

3.3.2. Muscle

Skeletal muscle is highly vascularized and exhibits adaptive responses in microvessels based on muscle demand. Patients who underwent mud therapy (in all three modalities of application) demonstrated an increased number of angiogenesis vessels per microscopic field (

Table 4).

In muscle tissue, the cold mud ointment plot exhibited the highest mean of angiogenesis vessels per microscopic field, with 5.70 ± 0.82, similar to the mud pack plot, which had 5.40 ± 0.84. This was significantly different compared to the witness plot, where 2.2 ± 0.84 were counted, and the mud bath plot, where 3.20 ± 0.79 were counted (

Table 5).

The high number of angiogenesis vessels observed in the cold mud ointment plot reflects an adaptive microvascular response to the decrease in muscle temperature. Compared to the witness plot, significant differences in the number of angiogenesis vessels per microscopic field were found in muscle tissue for the mud pack, mud bath, and cold mud ointment plots (H = 26.217, df = 3, p < 0.001 < α = 0.05). The mean ranks of scores were 5.00 for the witness plot group, 24.40 for the mud pack plot group, 9.70 for the mud bath plot group, and 26.40 for the cold mud ointment plot group.

Post hoc tests revealed statistically significant differences between mud pack and mud cold ointment (padj = 0.001 < α = 0.05) and between mud bath and mud cold ointment (padj = 0.006 < α = 0.05). However, there was no significant difference between mud pack and mud bath in terms of angiogenesis vessel count (padj > 0.05). Additional confirmation with the median test showed significant differences only between mud pack and mud cold ointment (χ2 = 9.348, df = 3, p = 0.025 < α = 0.05). The distribution of the number of angiogenesis vessels is illustrated graphically in

Figure 7.

Statistical analysis revealed that patients who received mud therapy in all three modalities exhibited a higher number of angiogenesis vessels, with statistically significant differences observed in mud pack and mud cold ointment treatments. However, there was no statistically significant difference between mud pack and mud cold ointment treatments. Conversely, the number of angiogenesis vessels observed in the thermal neutral applications (witness plot and mud bath plot) did not show statistical significance.

This indicates that mud pack and mud cold ointment therapies elicit distinct microvascular responses compared to both thermal neutral applications and each other.

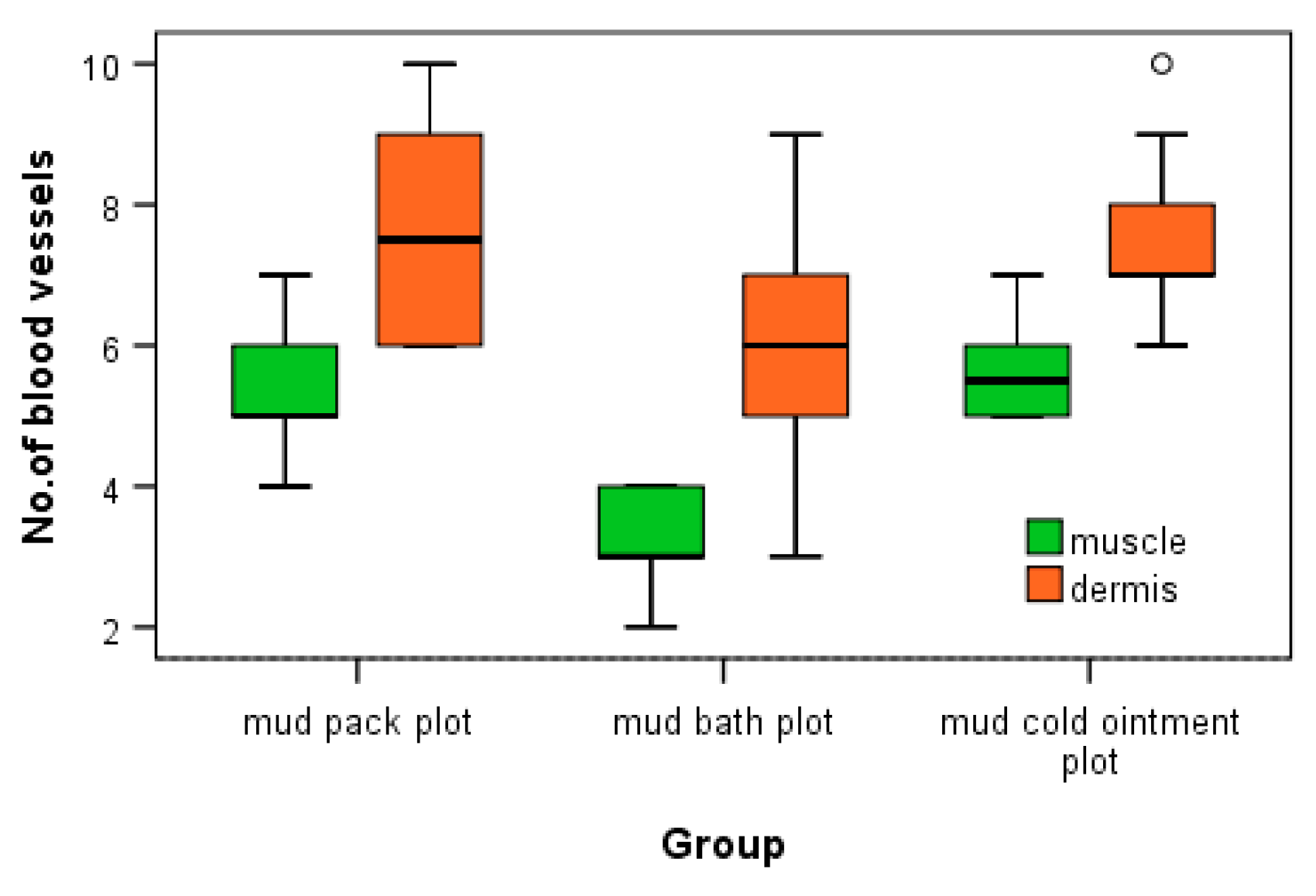

3.4. Comparison between Angiogenesis Vessels in Dermis and Muscle Tissue

Statistical analysis indicated a statistically significant increase in the number of angiogenesis vessels per microscopic field for both mud cold ointment and mud pack treatments in both dermal and muscle tissues. To assess the differences in the number of angiogenesis vessels between dermal and muscle tissues within each type of mud application, Mann-Whitney U tests were performed. In all cases, the tests showed significant differences in the number of blood vessels between dermal and muscle tissues (p < 0.05*), as summarized in

Table 6.

Statistical analysis reveals that the increase in the number of angiogenesis vessels in both dermis and muscle tissues is statistically significant across all forms of mud therapy. The graphic representation of the distribution of angiogenesis vessels in dermis and muscle tissues highlights the differences observed in the number of angiogenesis vessels (

Figure 8).

The increased number of angiogenesis vessels in both dermis and muscle following mud therapy demonstrates statistical significance, with variations influenced by several factors: the thermal regimen (significant for hyperthermal and contrast thermal therapy), tissue depth and temperature (significant in dermis for mud pack and in muscle for mud cold ointment), and the abolishment of sweating in a humid environment (significant for mud pack). The number of angiogenesis vessels in dermis after mud bath may be influenced by the abolishment of sweating in a humid environment and the participation of hydrogen sulfide. Heat plays a critical role in opening capillary shunts and increasing capillary caliber.

4. Discussion

Angiogenesis, the process of new capillary growth from existing vasculature, is enhanced in conditions involving increased local and central temperatures and the abolishment of sweating in a humid environment, as observed in mud pack therapy. We hypothesize that to maintain thermal homeostasis, an increased vascular network is necessary to store and dissipate heat effectively, including the opening of capillary shunts and the formation of new blood vessels through angiogenesis, which is stimulated by exogenous hydrogen sulfide present in mud.

In cold mud ointment therapy, rapid alternations between local and central temperature changes through heating and cooling promote swift transitions from vasodilation to vasoconstriction. This mechanism ensures adequate muscle blood flow by locally adjusting the number of open capillaries and facilitating non-shivering thermoregulation.

Due to these distinct mechanisms, mud pack therapy (hyperthermal) results in higher angiogenesis in the dermis, whereas cold mud ointment therapy shows superior angiogenesis in muscle tissue.

In mud bath therapy (thermal neutral), the number of angiogenesis vessels is higher compared to the witness plot but lower than mud pack and cold mud ointment therapies. The difference between the witness plot and mud bath plot (both thermal neutral) may be attributed to mud compounds, such as hydrogen sulfide, which penetrate the skin and contribute to angiogenesis.

The presence of pericytes in the dermis and muscle tissue twenty-four hours after completing the therapy course suggests that morphological changes continue even after treatment cessation.

5. Conclusions

This histological approach provides a visual representation of morphological changes induced in the dermis and muscle following a two-week balneotherapy regimen with hypersaline water and mud. Statistical analysis helps to elucidate the empirical aspects surrounding balneology and balneotherapy.

Our study demonstrates that natural therapeutic factors are pivotal in eliciting histological modifications through functional stimulation. Repeated topical heat treatments under various thermal regimens (hyperthermal, thermal neutral, thermal contrast), with options for sweating or its abolishment, and the penetration of biochemical compounds (such as hydrogen sulfide and sulfur species) from hypersaline water and mud during a balneal course, lead to statistically significant histological modifications in both dermis and muscle tissues, persisting for at least twenty-four hours post-treatment.

However, the study has limitations including a small sample size for each type of mud application, lack of follow-up data, and absence of temperature measurements. Building upon these histological findings, further research is warranted to explore the cellular and molecular mechanisms of angiogenesis induced by balneotherapy. Additionally, investigations into the broader impact of the entire balneal environment (including climate, heat energy transfer, entropy variations, epigenetics, and nanoparticles) on the human body are crucial for a comprehensive understanding.

Author Contributions

OS – conceptualisation; MCM and TVS– Methodology; AP Software; RET and MCM – Validation; OS and TVS - Formal analysis; RET and MS – Investigation; MCM and MS and TVS – Resources; OS and AP and AIT - Data curation; OS and TVS and MS - Writing - original draft preparation; OS and TVS and RET - Writing review and editing; AP – Visualisation; OS – Supervision; OS - Project administration;

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Techirghiol Balneal and Rehabilitation Sanatorium no 23/11/07/2018)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study before enrolment. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper keeping their confidentiality..

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The histological blades and acquired images are in the histoteque of Faculty of Medicine of Constanta.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Carbajo, J.M.; Maraver, F. Sulphurous Mineral Waters: New Applications for Health. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carretero, M. Clay minerals and their beneficial effects upon human health. A review. Appl. Clay Sci. 2002, 21, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.; Carretero, M.I.; Pozo, M.; Maraver, F.; Cantista, P.; Armijo, F.; Legido, J.L.; Teixeira, F.; Rautureau, M.; Delgado, R. Peloids and pelotherapy: Historical evolution, classification and glossary. Appl. Clay Sci. 2013, 75-76, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, M.; Carretero, M.I.; Maraver, F.; Pozo, E.; Gómez, I.; Armijo, F.; Rubí, J.A.M. Composition and physico-chemical properties of peloids used in Spanish spas: A comparative study. Appl. Clay Sci. 2013, 83-84, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulkern R, McDannold N, Hynynen K et al. Temperature distribution change in low back muscles during applied topical heat: A magnetic resonance thermometry study. 22 May 1999; -28.

- Reid, R.W.; Foley, J.M.; Prior, B.M.; Weingand, K.W.; Meyer, R.A. MILD TOPICAL HEAT INCREASES POPLITEAL BLOOD FLOW AS MEASURED BY MRI. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1999, 31, S208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch EN, Gibson OR, Khir AW, González-Alonso J Regional thermal hyperemia in the human leg: evidence of the importance of thermosensitive mechanisms in the control of the peripheral circulation. Physiol Rep 9:14953. [CrossRef]

- Egginton, S.; Zhou, A.-L.; Brown, M.; O Hudlická, O. Unorthodox angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Cardiovasc. Res. 2001, 49, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, R.L.; Pevec, W.C.; Ndoye, A.; Cheung, A.T.; Sasse, J.; Pearson, D.N. Regulation of new blood vessel growth into ischemic skeletal muscle. J. Vasc. Surg. 1998, 28, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- law 343/31st, May, 2002.

- Norms for application of balneal law approved by Decision No. 1154 of 23 July 2004.

- Framework Contract 2021 – 2022 approved June, the 28th 2021 and;

- Leiva-Cepas, et All (2018). Laboratory methodology for the histological study of skeletal muscle. Archivos de Medicina del Deporte. 35. 254-262.

- Kolarsick, P.A.J.B.; Kolarsick, M.A.M.; Goodwin, C.A.-B. Anatomy and Physiology of the Skin. J. Dermatol. Nurses' Assoc. 2011, 3, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooventhan, A.; Nivethitha, L. Scientific evidence-based effects of hydrotherapy on various systems of the body. North Am. J. Med Sci. 2014, 6, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortensen, S.P.; Saltin, B. Regulation of the skeletal muscle blood flow in humans. Exp. Physiol. 2014, 99, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Wei, R.; Ge, T.; Zheng, X.; Li, B.; Liu, K.; Cui, R. Hydrogen sulfide: A new therapeutic target in vascular diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 934231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, J.; Tyagi, S.C.; Tyagi, N. Role of hydrogen sulfide in the musculoskeletal system. Bone 2019, 124, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunescu R.; et al. Studii şi cercetări de balneologie şi fizioterapie. Ed. Medicală Bucureşti 1967. Vol. IX pag. 485 - 486.

- Agirbiceanu T. Et al, Studii şi cercetări de balneologie şi fizioterapie”, vol VI, Ed. Medicală Bucureşti, 1964;

- Wang, M.-J.; Cai, W.-J.; Li, N.; Ding, Y.-J.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.-C. The Hydrogen Sulfide Donor NaHS Promotes Angiogenesis in a Rat Model of Hind Limb Ischemia. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2010, 12, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streeter, E.; Ng, H.H.; Hart, J.L. Hydrogen sulfide as a vasculoprotective factor. Med Gas Res. 2013, 3, 9–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).