Submitted:

19 July 2024

Posted:

19 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

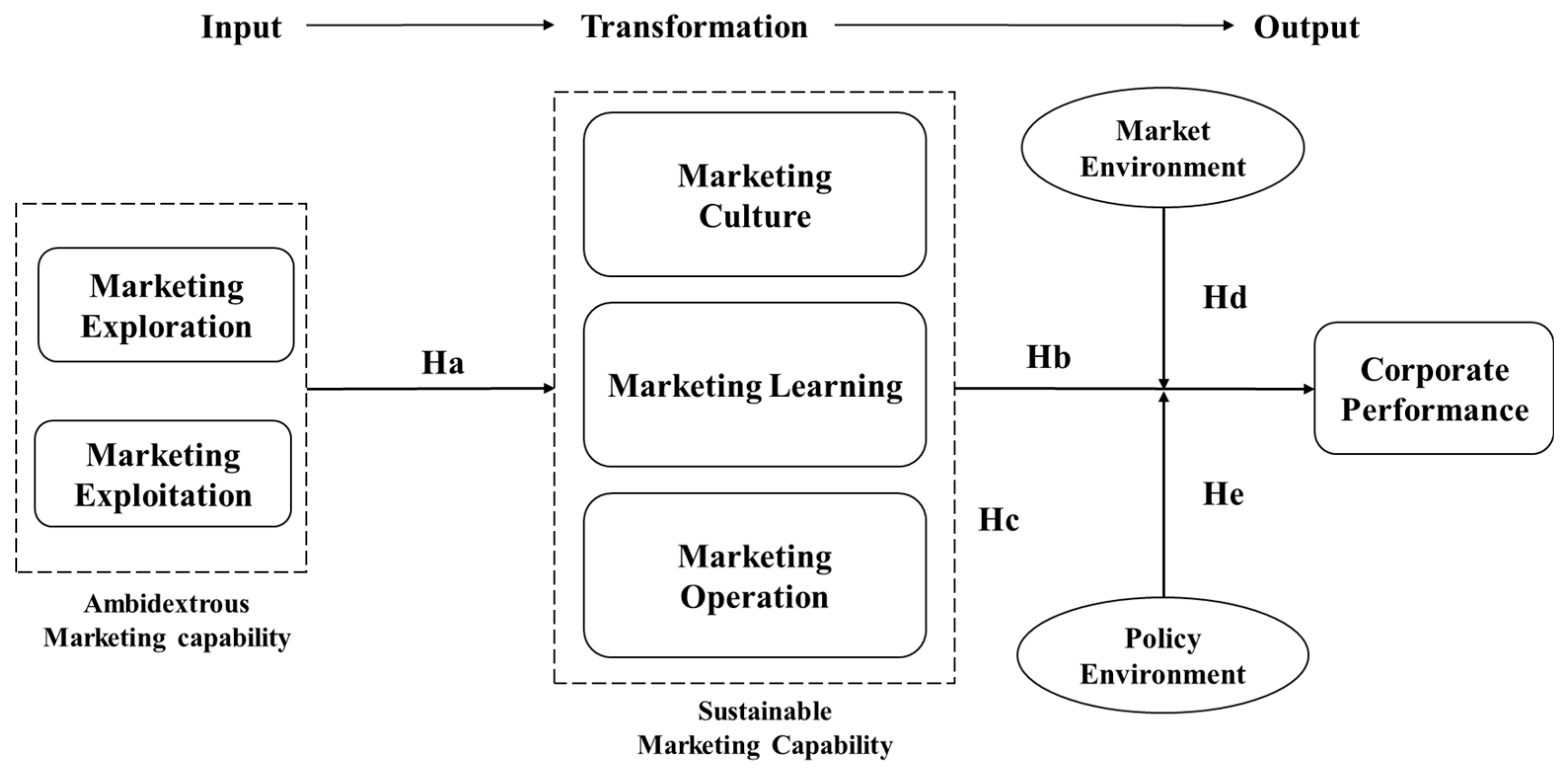

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Ambidexterity Theory

2.2. Ambidextrous Marketing Capability

2.3. Sustained Marketing Capability

2.4. Ambidextrous Marketing Capability and Sustained Marketing Capability

2.5. Sustainable Marketing Capability and Corporate Performance

2.6. The Mediating Role of Sustainable Marketing Capability

2.7. The Moderating Effect of Policy and Market Environments

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement

3.2. Sampling

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Reliability and Validity

4.3. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlation Analysis of Variables

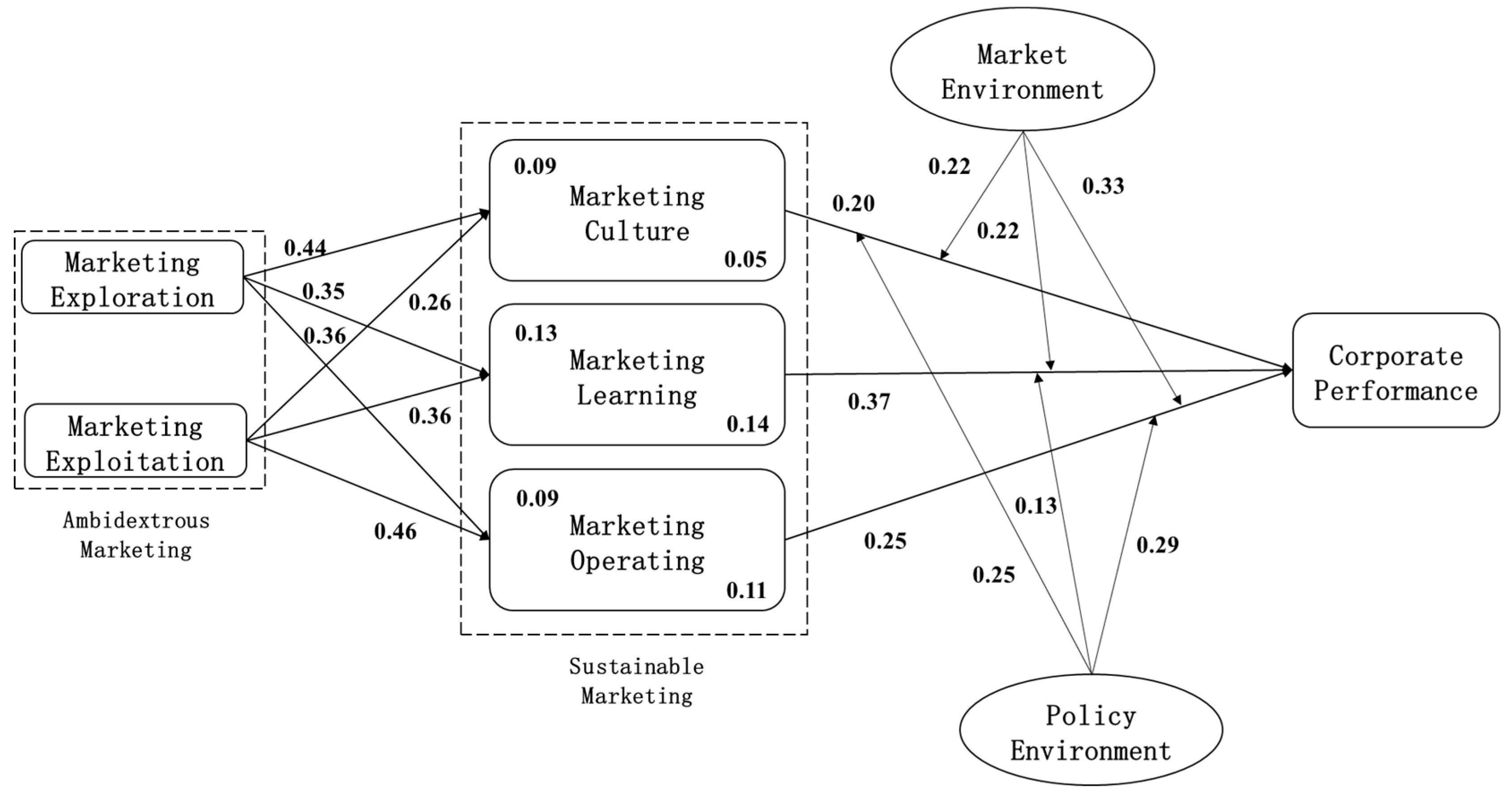

4.4. Structural Model Analysis

4.5. Mediation Analysis

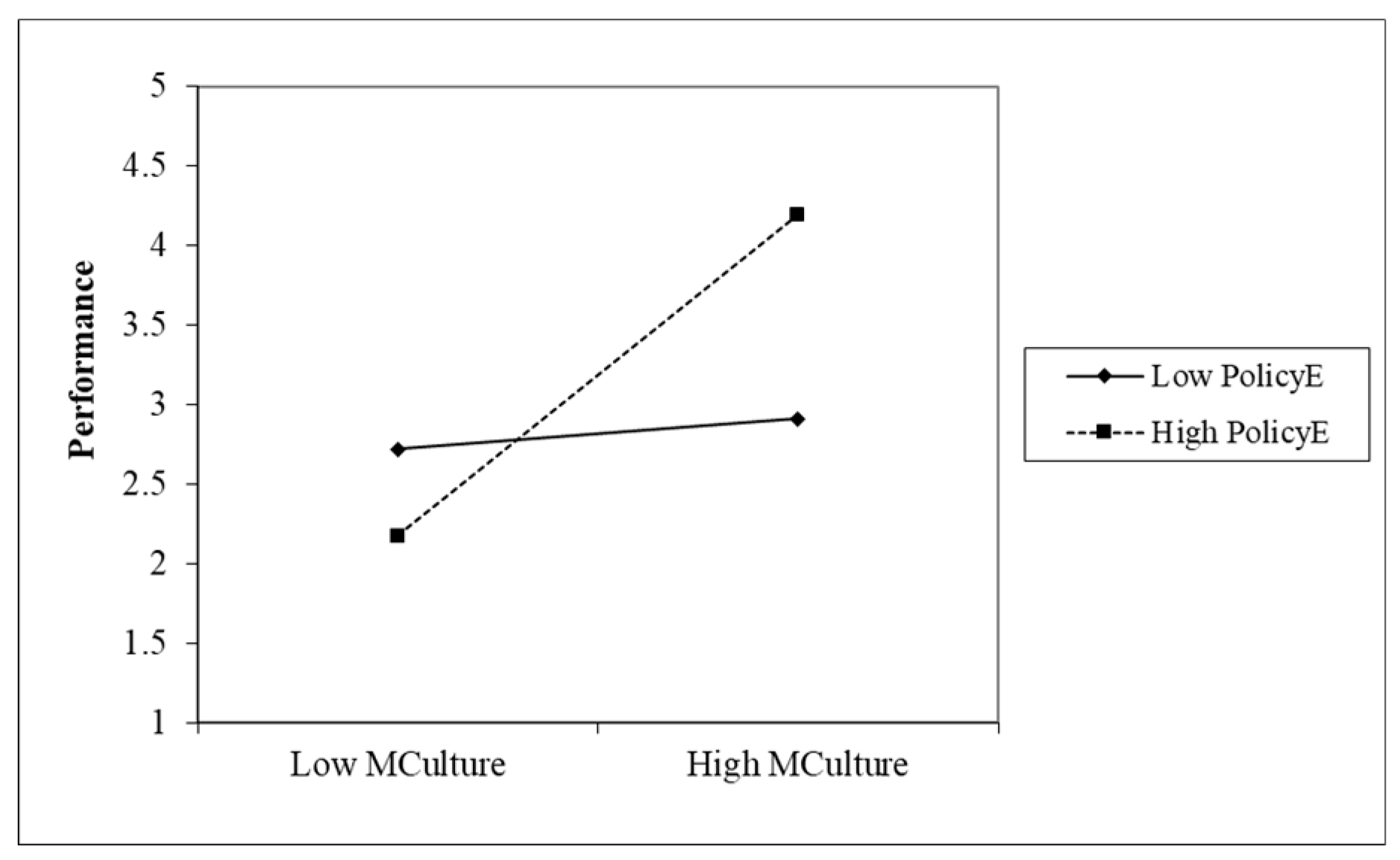

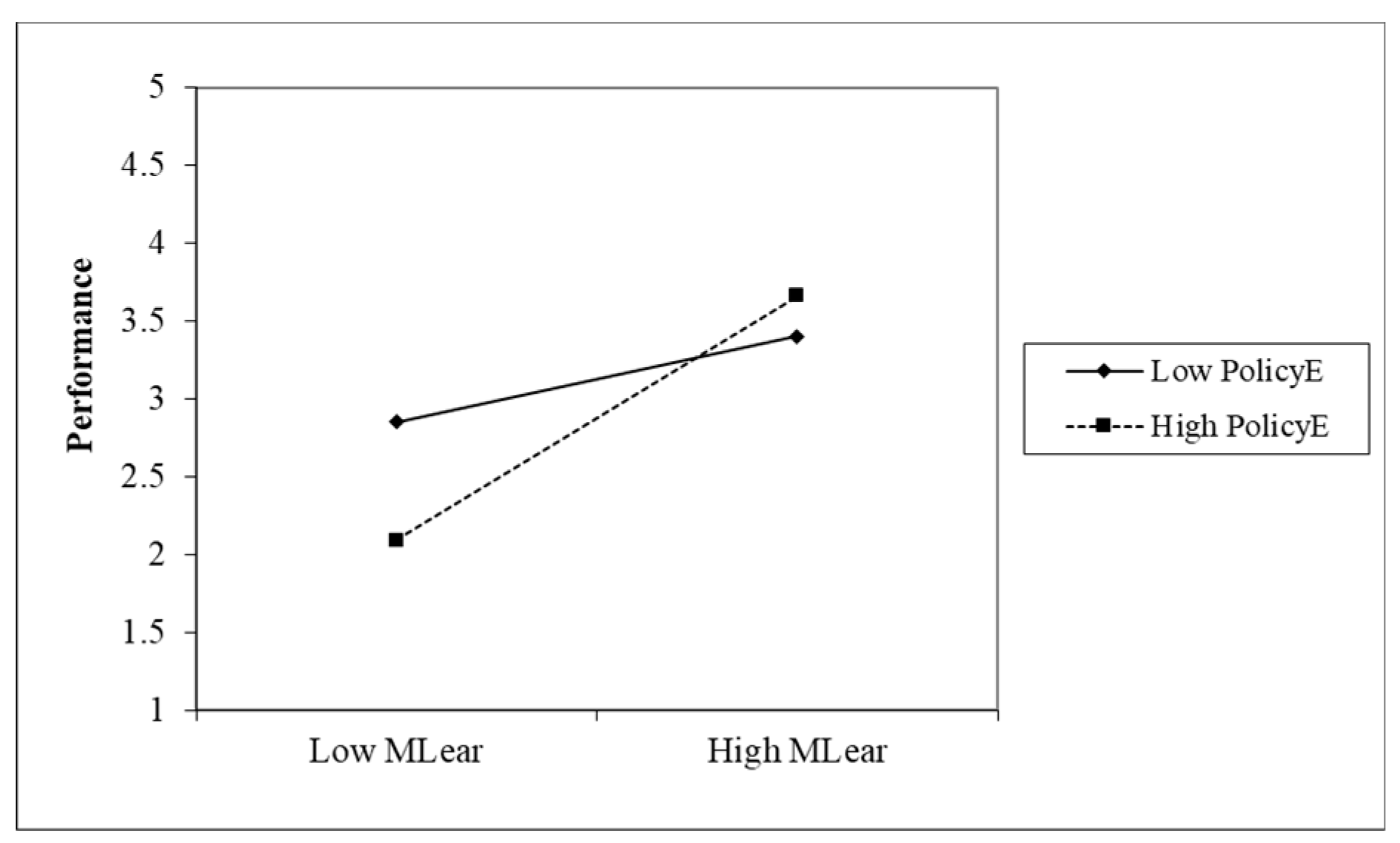

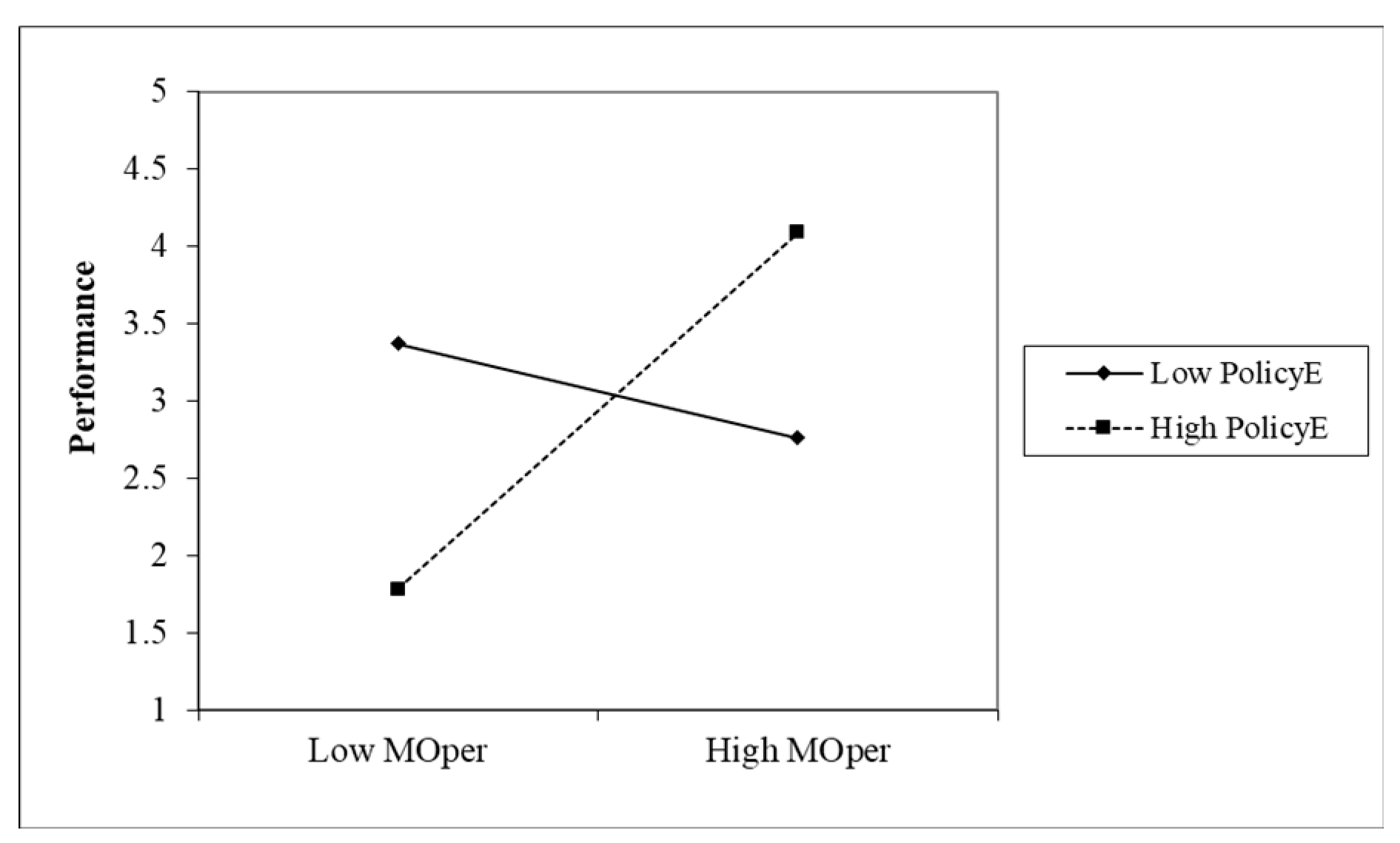

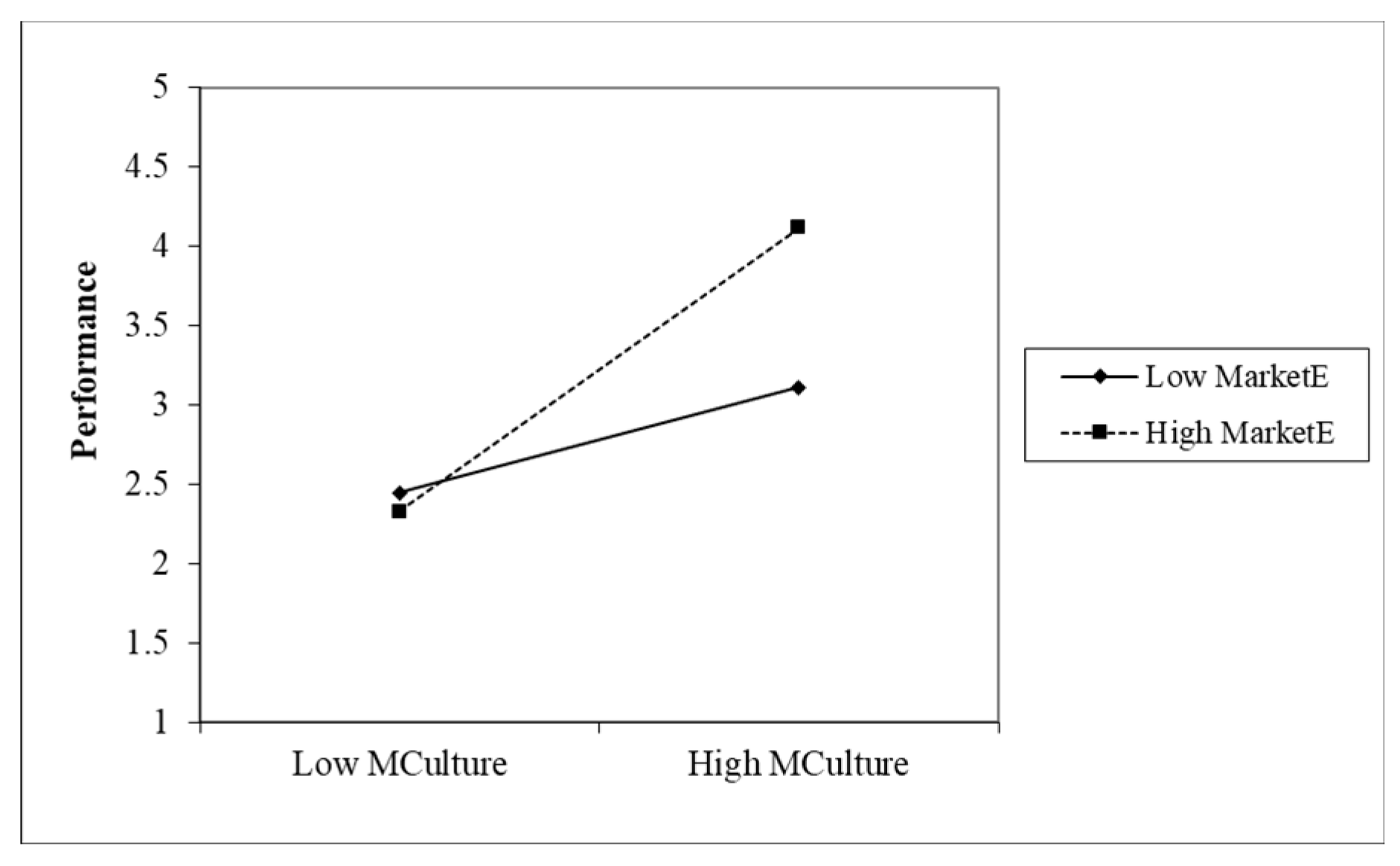

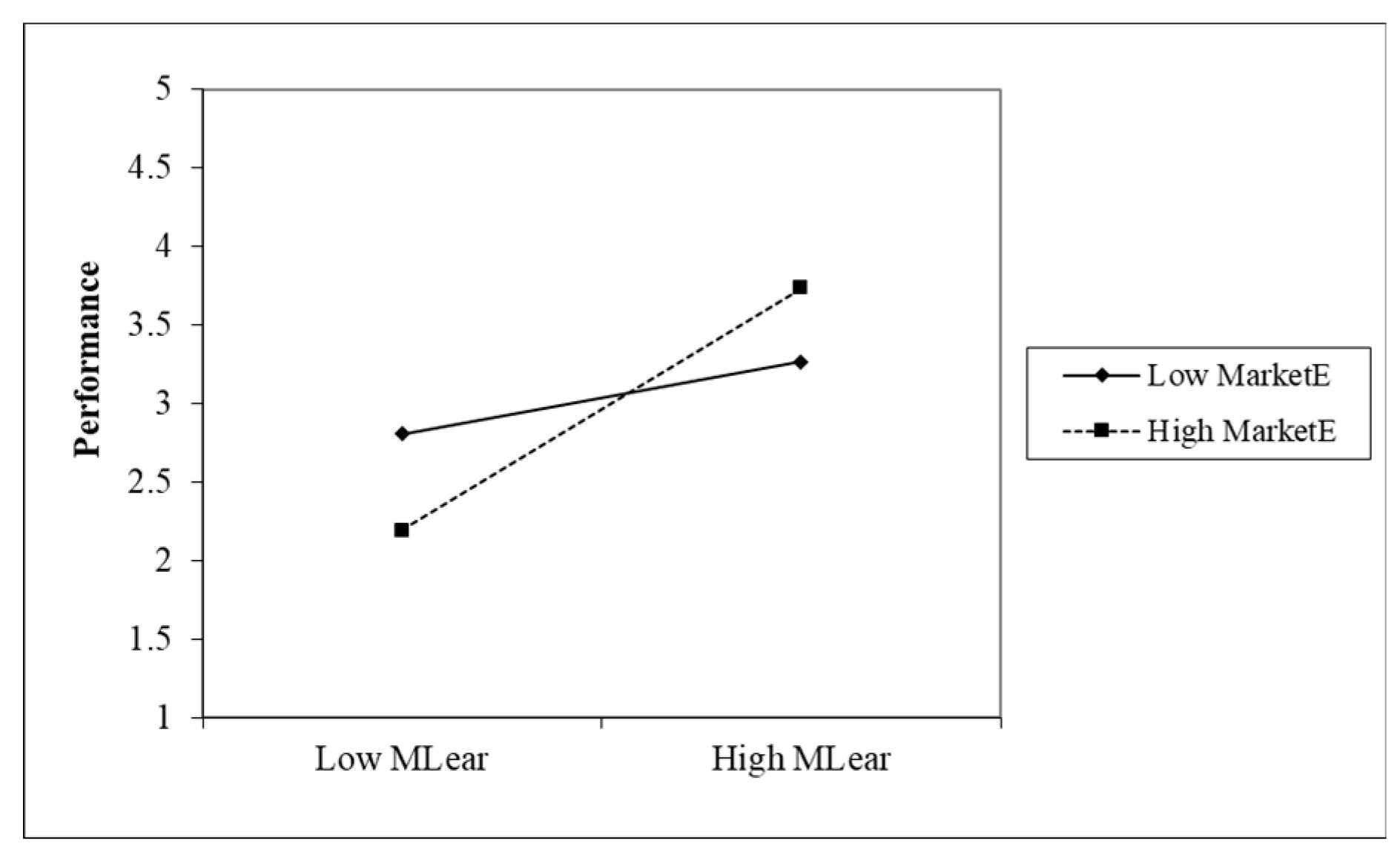

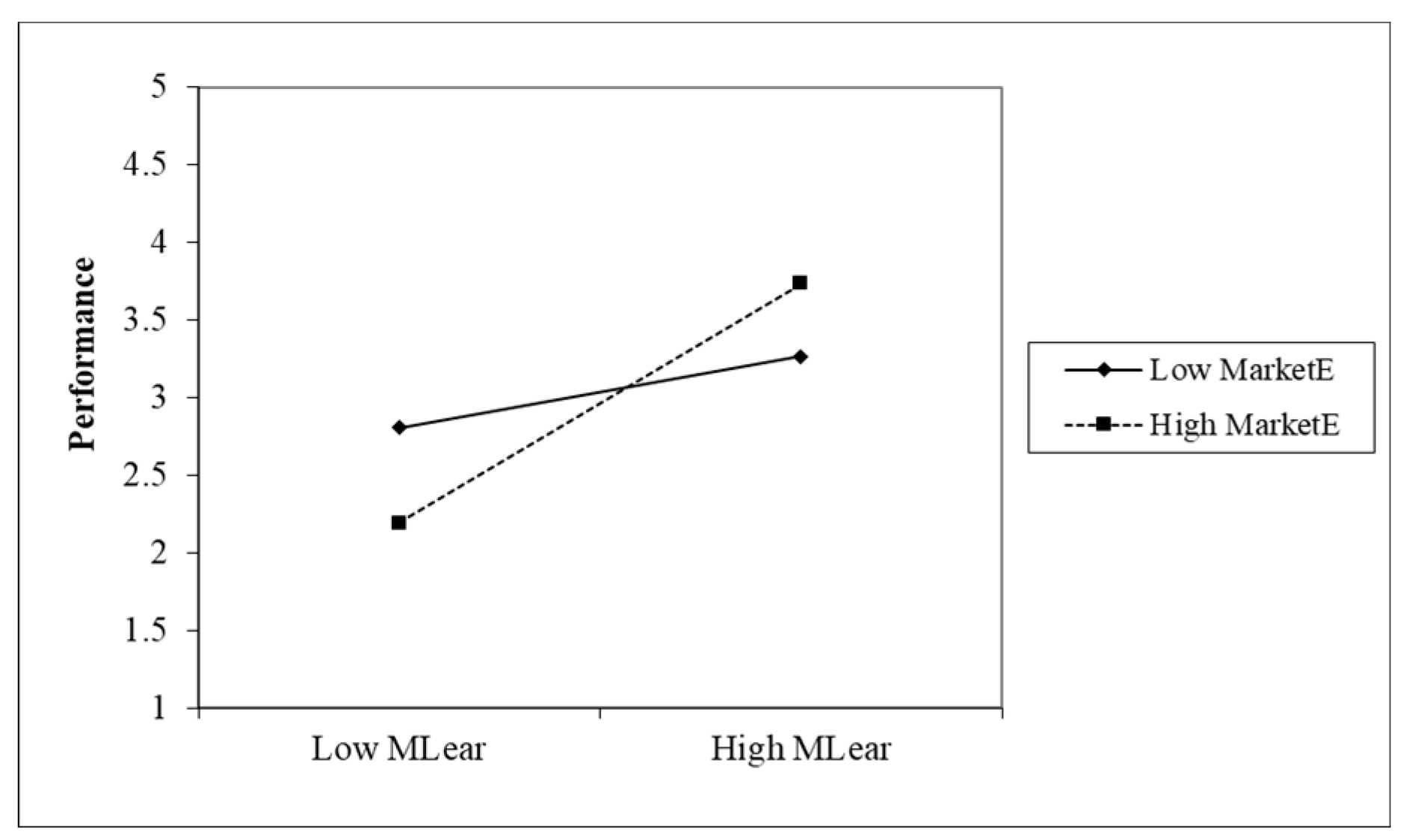

4.6. Moderating Effects Test

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Finding

5.2. Management Insights

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

References

- Li, C.; Cui, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhou, N. Brand Revitalization of Heritage Enterprises for Cultural Sustainability in the Digital Era: A Case Study in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1769. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-N.; Li, Y.-Q.; Liu, C.-H.; Ruan, W.-Q. A Study on China’s Time-Honored Catering Brands: Achieving New Inheritance of Traditional Brands. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2021, 58, 102290. [CrossRef]

- Ke, D.; Li, G.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Research on the Innovation of Time-Honored Brands from the Perspective of Dual Ethical Patterns. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1041022. [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Peng, C. The Effect of Dynamic Capability on Sustained Competitive Advantage of Enterprise: The Mediating Role of Ambidextrous Innovation Synergy. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Economic Management and Cultural Industry (ICEMCI 2022); Mallick, H., B., G.V., San, O.T., Eds.; Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research; Atlantis Press International BV: Dordrecht, 2023; Vol. 231, pp. 1096–1105 ISBN 978-94-6463-097-8.

- Wei, H, S. Study on the Relationship between Sustainable Marketing Capability of Xinjiang SMES and Enterprises Performance. Science Technology and Industry 2015, 15, 9–14. [CrossRef]

- Boumgarden, P.; Nickerson, J.; Zenger, T.R. Sailing into the Wind: Exploring the Relationships among Ambidexterity, Vacillation, and Organizational Performance. Strategic Management Journal 2012, 33, 587–610. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, N. Know Yourself and Find Your Partners: Achieving Ambidexterity and Inter-Organizational Collaboration. MRR 2019, 42, 1333–1352. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C, L., Shen, H., Zhang, J., Huang, Y. Slack Resources, Ambidextrous Innovation and Sustained Competitive Advantages—Based on the Perspective of Resource Bricolage. East China Economic Management. 2017, 31, 124–133. [CrossRef]

- Lučić, A. Measuring Sustainable Marketing Orientation—Scale Development Process. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1734. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Hu, A. Big Data Capability and Sustainable Competitive Advantage: The Mediating Role of Ambidextrous Innovation Strategy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8249. [CrossRef]

- Kotler P. Rethinking Marketing: Sustainable Market-ing Enterprise in Asia Text and Cases. Beijing. China Renming University Press, 2004, P3; ISBN 978-7-300-05092-8.

- Wang,L,Z., & Xu,Z,L. A research on the structure of sustainable marketing capability of enterprises. Journal of Industrial Technological Economics 2007, 11–14.

- Kunieda, Y.; Takashima, K. Dynamic Resource Allocation between Exploration and Exploitation. MRR 2021, 44, 738–756. [CrossRef]

- Xu,W.,Yang,W,C.,Li,Y,F. The Innovation Achievement Path and Its Model of Time-Honored Brand. Chinese Journal of Management. 2020, 17, 1535–1543. [CrossRef]

- Wang.D.S, Yang.Z.H, Jie.H. The Influencing Mechanism of Time-honored Brand Story Theme on Brand Attitude. Journal of Central University of Finance & Economics, 2021, 88–99. [CrossRef]

- Zhu. X.T, Luo. M.T. Research on the influence of brand extension of time-honored products on consumer loyalty. Price: Theory & Practice, 2022, (12),132–136. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, B.L. Differential Social Perception and Attribution of Intergroup Violence: Testing the Lower Limits of Stereotyping of Blacks. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1976, 34, 590–598. [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organization Science 1991, 2, 71–87. [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.; Raubitschek, R. Product Sequencing: Co-Evolution of Knowledge, Capabilities and Products. Strategic Management Journal 2000, 21. [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, M. Experiential Learning Processes of Exploitation and Exploration Within and Between Organizations: An Empirical Study of Product Development. Organization Science 2004, 15, 70–81. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-L.; Wong, P.-K. Exploration vs. Exploitation: An Empirical Test of the Ambidexterity Hypothesis. Organization Science 2004, 15, 481–494. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Smith, K.G.; Shalley, C.E. The Interplay Between Exploration and Exploitation. AMJ 2006, 49, 693–706. [CrossRef]

- Sirén, C.A.; Kohtamäki, M.; Kuckertz, A. Exploration and Exploitation Strategies, Profit Performance, and the Mediating Role of Strategic Learning: Escaping the Exploitation Trap. Strategic Entrepreneurship 2012, 6, 18–41. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Exploratory Innovation, Exploitative Innovation, and Performance: Effects of Organizational Antecedents and Environmental Moderators. Management Science 2006, 52, 1661–1674. [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity: Past, Present, and Future. AMP 2013, 27, 324–338. [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R. A Model of Strategic Entrepreneurship: The Construct and Its Dimensions. Journal of Management 2003, 29, 963–989. [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, D.; Mazilu, D.; Malomed, B.A.; Lederer, F. Stable Vortex Solitons Supported by Competing Quadratic and Cubic Nonlinearities. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 69, 066614. [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Tushman, M.L. Managing Strategic Contradictions: A Top Management Model for Managing Innovation Streams. Organization Science 2005, 16, 522–536. [CrossRef]

- Lavie, D.; Kang, J.; Rosenkopf, L. Balance Within and Across Domains: The Performance Implications of Exploration and Exploitation in Alliances. Organization Science 2011, 22, 1517–1538. [CrossRef]

- Simsek, Z.; Heavey, C.; Veiga, J.F.; Souder, D. A Typology for Aligning Organizational Ambidexterity’s Conceptualizations, Antecedents, and Outcomes. J Management Studies 2009, 46, 864–894. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Rui, H. An Ambidexterity Perspective Toward Multinational Enterprises From Emerging Economies. Academy of Management Perspectives 2009.

- Li, Y.; Peng, M.W.; Macaulay, C.D. Market–Political Ambidexterity during Institutional Transitions. Strategic Organization 2013, 11, 205–213. [CrossRef]

- Fang, T. Yin Yang: A New Perspective on Culture. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2012, 8, 25–50. [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J.; Probst, G.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity: Balancing Exploitation and Exploration for Sustained Performance. Organization Science 2009, 20, 685–695. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.B.; Birkinshaw, J. THE ANTECEDENTS, CONSEQUENCES, AND MEDIATING ROLE OF ORGANIZATIONAL AMBIDEXTERITY. Academy of Management Journal 2004.

- Shen, J. Retrospect, Analysis and Prospect of Organizational Ambidexterity. Forum on Science and Technology in China, 2011, 07, 114–121. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, K.; Moorman, C. Tradeoffs in Marketing Exploitation and Exploration Strategies: The Overlooked Role of Market Orientation. International Journal of Research in Marketing 2004, 21, 219–240. [CrossRef]

- Prange, C.; Schlegelmilch, B.B. The Role of Ambidexterity in Marketing Strategy Implementation: Resolving the Exploration-Exploitation Dilemma. Bus Res 2009, 2, 215–240. [CrossRef]

- Vorhies, D.W.; Orr, L.M.; Bush, V.D. Improving Customer-Focused Marketing Capabilities and Firm Financial Performance via Marketing Exploration and Exploitation. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 736–756. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Gedajlovic, E.; Zhang, H. Unpacking Organizational Ambidexterity: Dimensions, Contingencies, and Synergistic Effects. Organization Science 2009, 20, 781–796. [CrossRef]

- Ho, H. (Dixon); Lu, R. Performance Implications of Marketing Exploitation and Exploration: Moderating Role of Supplier Collaboration. Journal of Business Research 2015, 68, 1026–1034. [CrossRef]

- Peng,Z,L., He,P,X., and Li,Z. Balance of Ambidextrous Marketing Capabilities, Strategic Positional Advantages and New High-tech Service Venture Performance. Journal of Management Science, 2015, 28(03), 115–129. doi: 0.3969/j.issn.1672-0334.2015.03.010.

- Sun, W.; Price, J.M. Implications of Marketing Capability and Research and Development Intensity on Firm Default Risk. Journal of Marketing Management 2016, 32, 179–206. [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, H.; Coviello, N.; Ranaweera, C. Ambidextrous Marketing Capabilities and Performance: How and When Entrepreneurial Orientation Makes a Difference. Industrial Marketing Management 2019, 77, 129–142. [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.; Osiyevskyy, O.; Agarwal, J.; Reza, S. Does Ambidexterity in Marketing Pay off? The Role of Absorptive Capacity. Journal of Business Research 2020, 110, 65–79. [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Pei, Y.; Lin, C.; Ye, D. Ambidextrous Marketing Capabilities, Exploratory and Exploitative Market-Based Innovation, and Innovation Performance: An Empirical Study on China’s Manufacturing Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1146. [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Cui, A.P.; Samiee, S.; Zou, S. Exploration, Exploitation, Ambidexterity and the Performance of International SMEs. EJM 2022, 56, 1372–1397. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D. The Nature and Scope of Marketing. Journal of Marketing 1976.

- Day, G.S. The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations. Journal of Marketing 1994, 58, 37–52. [CrossRef]

- Vorhies, D.W.; Morgan, N.A. Benchmarking Marketing Capabilities for Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Journal of Marketing 2005, 69, 80–94. [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management 1991, 17, 99–120. [CrossRef]

- Day, G. Closing the Marketing Capabilities Gap. Journal of Marketing 2011, 75, 183–195. [CrossRef]

- Webster, F.E. The Changing Role of Marketing in the Corporation. Journal of Marketing 1992, 56, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Hooley, G.; Broderick, A.; Möller, K. Competitive Positioning and the Resource-Based View of the Firm. Journal of Strategic Marketing 1998, 6, 97–116. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.A. Marketing and Business Performance. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 102–119. [CrossRef]

- Pfajfar, G.; Mitręga, M.; Shoham, A. Systematic Review of International Marketing Capabilities in Dynamic Capabilities View – Calibrating Research on International Dynamic Marketing Capabilities. IMR 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hooley, G.; Fahy, J.; Cox, T.; Beracs, J.; Fonfara, K.; Snoj, B. Marketing Capabilities and Firm Performance: A Hierarchical Model.

- Wang, A, P. The Choices for the Approaches Enhancing Enterprise Marketing Capabilities in the Age of Knowledge Economy. On Economic Problems, 2017, 05, 79–83. [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Rahman, Z. Market Orientation, Marketing Capabilities and Sustainable Innovation: The Mediating Role of Sustainable Consumption and Competitive Advantage. MRR 2017, 40, 698–724. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D. Strategic Marketing, Sustainability, the Triple Bottom Line, and Resource-Advantage (R-A) Theory: Securing the Foundations of Strategic Marketing Theory and Research. AMS Rev 2017, 7, 52–66. [CrossRef]

- Sinčić Ćorić, D.; Lučić, A.; Brečić, R.; Šević, A.; Šević, Ž. An Exploration of Start-Ups’ Sustainable Marketing Orientation (SMO). Industrial Marketing Management 2020, 91, 176–186. [CrossRef]

- Appiah-Nimo, C.; Chovancová, M. Improving Firm Sustainable Performance: The Role of Market Orientation. Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence 2020, 14, 780–787. [CrossRef]

- Ling, H., Li, X, Y., and Xu, H, N. Digital Transformation, Dual Ability, and Enterprise Persistent Innovation. Journal of Technological Economics, 2023, 42, 48–57. [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. A Blueprint for Sustainability Marketing: Defining Its Conceptual Boundaries for Progress. Marketing Theory 2016, 16, 232–249. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Parvatiyar, A. Sustainable Marketing: Market-Driving, Not Market-Driven. Journal of Macromarketing 2021, 41, 150–165. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.,& Qiu, W. Mechanism and Balance of Exploratory and Exploitative Market-based Innovation. Journal of Management Science, 2021, 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y, Y.(2021). A research on relationship among marketing ambidexterity, absorptive capacity, and marketing performance. Journal of Guizhou University of Finance and Economics.2,51-61.

- Li,J,X.,& Zheng, R,K. Impact of Entrepreneurial Culture on High-Tech Firm Performance: Roles of Ambidextrous Innovation and Marketing Capability. Journal of Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (Social Sciences Edition), 2021, 34, 85–93. [CrossRef]

- Xu,Z,L., & Wang,L,Z. Relationships between sustainable marketing capability and business performance. Jilin University Journal Social Sciences Edition, 2007, 62–70.

- Lyu, C.; Peng, C.; Li, R.; Yang, X.; Cao, D. Ambidextrous Leadership and Sustainability Performance: Serial Mediation Effects of Employees’ Green Creativity and Green Product Innovation. LODJ 2022, 43, 1376–1394. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shan, S.; Shou, Y.; Kang, M.; Park, Y.W. Sustainable Sourcing and Agility Performance: The Moderating Effects of Organizational Ambidexterity and Supply Chain Disruption. Australian Journal of Management 2023, 48, 262–283. [CrossRef]

- Xing; Liu; Wang; Shen; Zhu Environmental Regulation, Environmental Commitment, Sustainability Exploration/Exploitation Innovation, and Firm Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6001. [CrossRef]

- SIJABAT, E.A.S.; NIMRAN, U.; UTAMI, H.N.; PRASETYA, A. Ambidextrous Innovation in Mediating Entrepreneurial Creativity on Firm Performance and Competitive Advantage. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 2020, 7, 737–746. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wu, G.; Xie, H.; Xu, H. Ambidextrous Leadership and Sustainability-Based Project Performance: The Role of Project Culture. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2336. [CrossRef]

- Mumel, D.; Hocevar, N.; Snoj, B. How Marketing Communications Correlates With Business Performance. JABR 2011, 23. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes Sampaio, C.A.; Hernández Mogollón, J.M.; De Ascensão Gouveia Rodrigues, R.J. The Relationship between Market Orientation, Customer Loyalty and Business Performance: A Sample from the Western Europe Hotel Industry. Tourism and Hospitality Research 2020, 20, 131–143. [CrossRef]

- Asree, S. Ambidextrous Supply Chain in an Emerging Market: Impacts on Innovation and Performance. IJSCOR 2016, 2, 1. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. American Journal of Sociology.

- Pan, C.; Abbas, J.; Álvarez-Otero, S.; Khan, H.; Cai, C. Interplay between Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Green Culture and Their Role in Employees’ Responsible Behavior towards the Environment and Society. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 366, 132878. [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Qin, Q.; Tang, T. (Ya) The Influence of Marketing Innovations on Firm Performance under Different Market Environments: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10049. [CrossRef]

- Luan, C.; Tien, C.; Wu, P. Strategizing Environmental Policy and Compliance for Firm Economic Sustainability: Evidence from Taiwanese Electronics Firms. Bus Strat Env 2013, 22, 517–546. [CrossRef]

- Tshuma, S. Embrace Green Marketing or Lose Competitive Advantage: An Insight on the Performance of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in the Foundry Sector in Zimbabwe. Econ. manag. sustain. 2022, 7, 63–69. [CrossRef]

- Wang,X,J., & Sun,B. Transformational Business Model, Ambidextrous Marketing Capabilities and Value Creation. Journal of Guangdong University of Finance and Economics, 2017, 32, 34–45.

- Narver, J.C.; Slater, S.F. The Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Profitability. Journal of Marketing 1990, 54, 20–35. [CrossRef]

- Conduit, J.; Mavondo, F.T. How Critical Is Internal Customer Orientation to Market Orientation? Journal of Business Research 2001, 51, 11–24. [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Ferrell, O.C. Global Organizational Learning Capacity in Purchasing: Construct and Measurement. Journal of Business Research 1997, 40, 97–111. [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Beard, D.W. Dimensions of Organizational Task Environments. Administrative Science Quarterly 1984, 29, 52. [CrossRef]

- Doty, D.H.; Glick, W.H.; Huber, G.P. FIT, EQUIFINALITY, AND ORGANIZATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS: A TEST OF TWO CONFIGURATIONAL THEORIES. Academy of Management Journal 1993, 36, 1196–1250. [CrossRef]

- Vorhies, D.W.; Harker, M.; Rao, C.P. The Capabilities and Performance Advantages of Market-driven Firms. European Journal of Marketing 1999, 33, 1171–1202. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.R.; Lorsch, J.W. Differentiation and Integration in Complex Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 1967, 12, 1. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.C. The Contingency Theory of Managerial Accounting. The Accounting Review 1977, 52, 22–39.

- Merchant, K.A. The Design of the Corporate Budgeting System: Influences on Managerial Behavior and Performance. The Accounting Review 1981, 56, 813–829.

- Govindarajan, V. Appropriateness of Accounting Data in Performance Evaluation: An Empirical Examination of Environmental Uncertainty as an Intervening Variable. Accounting, Organizations and Society 1984, 9, 125–135. [CrossRef]

- Sohi, R.S. The Effects of Environmental Dynamism and Heterogeneity on Salespeople’s Role Perceptions, Performance and Job Satisfaction. European Journal of Marketing 1996, 30, 49–67. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A.; Robbins, D.K.; Robinson, R.B. The Impact of Grand Strategy and Planning Formality on Financial Performance. Strategic Management Journal 1987, 8, 125–134. [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A.; Ford, N.M.; Hartley, S.W.; Walker, O.C. The Determinants of Salesperson Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Marketing Research 1985, 22, 103. [CrossRef]

- Celuch, K.G.; Kasouf, C.J.; Peruvemba, V. The Effects of Perceived Market and Learning Orientation on Assessed Organizational Capabilities. Industrial Marketing Management 2002, 31, 545–554. [CrossRef]

- Acar, A.Z.; Zehir, C.; Tanriverdi, H. Identifying Organizational Capabilities as Predictors of Growth and Business Performance. The Business Review, Cambridge 2006, 5, 109–116.

- Li, H.; Atuahene-Gima, K. PRODUCT INNOVATION STRATEGY AND THE PERFORMANCE OF NEW TECHNOLOGY VENTURES IN CHINA. Academy of Management Journal 2001, 44, 1123–1134. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y, T., Gao, S, X., and Zhang, F. Research on the effect firm capabilities on green management under external environment—based on resource based view and institutional theory. Chinese Journal of Management, 2016, 13, 1851–1858. [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A. DOES LEADERSHIP MATTER? CEO LEADERSHIP ATTRIBUTES AND PROFITABILITY UNDER CONDITIONS OF PERCEIVED ENVIRONMENTAL UNCERTAINTY. 2001.

- Lu, L.Y.Y.; Yang, C. The R&D and Marketing Cooperation across New Product Development Stages: An Empirical Study of Taiwan’s IT Industry. Industrial Marketing Management 2004, 33, 593–605. [CrossRef]

- Jiang,X., & Ma,Y,Y. Environmental Uncertainty, Alliance Green revolution, and Alliance performance. Management Review, 2018, 30, 60–71. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall, 1998; ISBN 978-0-13-894858-0.

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. JAMS 1988, 16, 74–94. [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Singh, S. On the Use of Structural Equation Models in Experimental Designs: Two Extensions. International Journal of Research in Marketing 1991, 8, 125–140. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 382. [CrossRef]

| Indexes | Category | Frequency | % | Indexes | Category | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm Types | Firm Types II | ||||||

| Limited Liability Company | 208 | 59.1 | Private Enterprise | 252 | 71.6 | ||

| Limited company | 138 | 39.2 | State-owned enterprise | 78 | 22.2 | ||

| Sole Proprietorship | 6 | 1.7 | Foreign Investment | 12 | 3.4 | ||

| Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan | 10 | 2.8 | |||||

| Firm Age | Firm Size | ||||||

| 21 - 50 years | 306 | 86.9 | Medium enterprise | 157 | 44.6 | ||

| 11 - 20 years | 31 | 8.8 | Large enterprise | 130 | 36.9 | ||

| More than 51 years | 10 | 2.8 | Small Enterprise | 37 | 10.5 | ||

| Less than 5 years | 5 | 1.4 | Microenterprise | 28 | 8 | ||

| Respondent’s Position | Firm Industry | ||||||

| Other vice presidents | 85 | 24.1 | Pharmaceuticals & Biotechnology | 50 | 14.2 | ||

| General manager | 78 | 22.2 | Liquor production | 47 | 13.4 | ||

| Middle manage | 78 | 22.2 | Food | 45 | 12.8 | ||

| Vice President Marketing | 71 | 20.2 | Retailing | 44 | 12.5 | ||

| General staff | 29 | 8.2 | Catering services | 42 | 11.9 | ||

| Chairman of the board | 11 | 3.1 | Chemical industry | 22 | 6.3 | ||

| Firm Location | Commercial trade | 18 | 5.1 | ||||

| Shanghai | 76 | 21.6 | Diversified finance | 14 | 4 | ||

| Beijing | 52 | 14.8 | Durable goods | 14 | 4 | ||

| Jiangsu | 45 | 12.8 | Hospitalities | 11 | 3.1 | ||

| Zhejiang | 43 | 12.2 | Raw materials | 11 | 3.1 | ||

| Shandong | 30 | 8.5 | Industrial & Business services | 10 | 2.8 | ||

| Tianjin | 29 | 8.2 | Agricultural products | 9 | 2.6 | ||

| Guangdong | 25 | 7.1 | Textile, Apparel, and Jewelry | 9 | 2.6 | ||

| Sichuan | 21 | 6 | Sports | 4 | 1.1 | ||

| Liaoning | 16 | 4.5 | Power Equipment | 2 | 0.6 | ||

| Fujian | 15 | 4.3 | |||||

| Items | SFL | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Marketing Exploration | 0.554 | 0.861 | 0.861 | |

| We will regularly introduce bold, adventurous, or avant-garde marketing processes. | 0.804 | |||

| We will consistently develop innovative marketing processes that starkly differ from past marketing approaches. | 0.730 | |||

| We will continuously apply market knowledge to devise entirely new strategies that diverge from existing marketing processes. | 0.703 | |||

| We will employ market knowledge to break traditional patterns and create novel marketing processes that have not been utilized before. | 0.734 | |||

| We will continually acquire new marketing knowledge or skills that are groundbreaking for the company and even the entire industry. | 0.747 | |||

| 2. Marketing Exploitation | 0.520 | 0.844 | 0.843 | |

| We will focus on revolutionizing marketing processes to enhance efficiency and implementation effectiveness. | 0.690 | |||

| We will continually examine information from existing projects and learning experiences to improve our established marketing processes. | 0.716 | |||

| Throughout the development of new marketing processes, we will consistently adhere to and adapt existing concepts. | 0.741 | |||

| We will progressively refine or elevate our existing marketing processes. | 0.701 | |||

| We excel in summarizing and distilling current marketing experiences and accumulating systematic marketing knowledge. | 0.757 | |||

| 3. Marketing Culture | 0.589 | 0.877 | 0.877 | |

| The company's competitive advantage is built upon a thorough understanding of customer needs. | 0.795 | |||

| Employees who provide excellent service to customers can receive corresponding rewards within the company. | 0.722 | |||

| The company can swiftly respond to competitive actions that pose threats. | 0.786 | |||

| Each department of the company is capable of providing products and services with genuine value to its associated departments. | 0.760 | |||

| During cross-departmental collaboration, departments treat each other as customers. | 0.771 | |||

| 4. Marketing Learning | 0.552 | 0.860 | 0.860 | |

| The company can quickly identify changes in customer preferences for products. | 0.748 | |||

| The company conducts consumer evaluations of its products or services at least once a year. | 0.738 | |||

| When recognizing customer expectations for product or service improvements, all relevant departments in the company collaborate to meet these needs. | 0.728 | |||

| Supervisors from each department of the company regularly visit customers or potential customers. | 0.734 | |||

| Managers in the company know how to motivate each employee to create value for customers. | 0.765 | |||

| 5. Marketing Operations | 0.558 | 0.863 | 0.862 | |

| The company's management has clearly articulated the strategic approach to achieving marketing objectives. | 0.745 | |||

| The company's marketing strategy aligns with the current market conditions. | 0.744 | |||

| By offering differentiated products or services, the company gains a competitive advantage in the market. | 0.686 | |||

| The company's marketing mix strategy is more effective than that of competitors. | 0.790 | |||

| The company establishes long-term relationships with customers through the sale of products and services. | 0.765 | |||

| 6. Enterprise Performance | 0.629 | 0.944 | 0.944 | |

| Net Profit | 0.813 | |||

| Sales Profit Margin | 0.780 | |||

| Cash Flow | 0.773 | |||

| Return on Investment (ROI) | 0.804 | |||

| Operating Costs | 0.807 | |||

| Sales Growth Rate | 0.808 | |||

| Market Share | 0.775 | |||

| Development of New Products | 0.780 | |||

| Market Expansion | 0.780 | |||

| Research and Development Achievements | 0.807 | |||

| 7.Market Environment | 0.630 | 0.735 | 0.873 | |

| Customer demands change rapidly | 0.953 | |||

| Market competition is difficult to predict | 0.623 | |||

| Competition among peers is becoming increasingly intense | 0.615 | |||

| Most new products in the market are achieved through technological breakthroughs | 0.621 | |||

| The pace of technological change within the industry is very fast | 0.668 | |||

| 8.Policy Environment | 0.612 | 0.703 | 0.824 | |

| Government provides policies and projects conducive to the development of our company | 0.961 | |||

| The government provides necessary technical information and technical support to our company | 0.640 | |||

| The government provides direct fiscal policies to our company, including taxation and government subsidies | 0.616 | |||

| The government encourages companies to protect intellectual property rights | 0.561 | |||

| The government provides necessary legal support for our company to enter new markets | 0.515 | |||

| KMO=.935 Bartlett's χ2/ df =9.868,p < 0.000 | ||||

| Variables | Mean | SD | Explor | Exploit | MC | ML | MO | Perfo | PE | ME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explor | 5.536 | 0.616 | 0.744 | |||||||

| Exploit | 5.554 | 0.596 | .460** | 0.721 | ||||||

| MC | 5.503 | 0.654 | .460** | .356** | 0.767 | |||||

| ML | 5.571 | 0.617 | .394** | .409** | .420** | 0.743 | ||||

| MO | 5.540 | 0.598 | .437** | .479** | .396** | .429** | 0.747 | |||

| Perfo | 5.636 | 0.641 | .439** | .353** | .432** | .509** | .457** | 0.793 | ||

| PE | 5.580 | 0.625 | -.255** | -0.102 | -.495** | -.204** | -.243** | -.193** | 0.794 | |

| ME | 5.513 | 0.727 | -.257** | -0.073 | -.561** | -.276** | -.226** | -.173** | .692** | 0.782 |

| Variable Relationships | Estimates | P-Value | Hypothesis | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marketing Exploration→Marketing Culture | 0.44 | *** | Ha1 | accepted |

| Marketing Exploration→Marketing Learning | 0.35 | *** | Ha2 | accepted |

| Marketing Exploration→Marketing Operating | 0.36 | *** | Ha3 | accepted |

| Marketing Exploitation→Marketing Culture | 0.26 | *** | Ha4 | accepted |

| Marketing Exploitation→Marketing Learning | 0.36 | *** | Ha5 | accepted |

| Marketing Exploitation→Marketing Operating | 0.46 | *** | Ha6 | accepted |

| Marketing Culture→Enterprise Performance | 0.20 | *** | Hb1 | accepted |

| Marketing Learning→Enterprise Performance | 0.37 | *** | Hb2 | accepted |

| Marketing Operating→Enterprise Performance | 0.25 | *** | Hb3 | accepted |

| χ2 = 724.891 df = 544 χ2/df = 1.333 RMSEA = 0.031 GFI = 0.900 NFI = 0.902 TLI(NNFI) = 0.971 CFI = 0.973 | ||||

| Variable Relationships | Estimates | SE | Lower | Upper | P-Value | Hypothesis | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explore→MC→Performance | 0.09 | 0.038 | 0.030 | 0.180 | 0.003 | Hc1 | accepted |

| Explore→ML→Performance | 0.13 | 0.041 | 0.062 | 0.223 | 0.001 | Hc2 | accepted |

| Explore→MO→Performance | 0.09 | 0.033 | 0.034 | 0.161 | 0.001 | Hc3 | accepted |

| Exploit→MC→Performance | 0.05 | 0.023 | 0.018 | 0.108 | 0.002 | Hc4 | accepted |

| Exploit→ML→Performance | 0.14 | 0.042 | 0.066 | 0.230 | 0.001 | Hc5 | accepted |

| Exploit→MO→Performance | 0.11 | 0.037 | 0.051 | 0.198 | 0.000 | Hc6 | accepted |

| Variable Relationships | Estimates | P-Value | Hypothesis | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marketing Culture*Policy environment→Enterprise Performance | 0.246 | *** | Hd1 | accepted |

| Marketing Learning*Policy environment→Enterprise Performance | 0.132 | * | Hd2 | accepted |

| Marketing Operation*Policy environment→Enterprise Performance | 0.294 | *** | Hd3 | accepted |

| Marketing Culture*Market environment→Enterprise Performance | 0.224 | *** | He1 | accepted |

| Marketing Learning*Market environment→Enterprise Performance | 0.222 | *** | He2 | accepted |

| Marketing Operation*Market environment→Enterprise Performance | 0.329 | *** | He3 | accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).