1. Introduction

The world’s population is aging rapidly with projections indicating that by 2050 there will be 2.1 billion people over the age of 65 in the world[

1]. In Brazil, demographic data suggests that the number of elderly people will increase from 32 million in 2023 to 66 million in 2050 [

2], indicating that additional spending will be necessary due to population aging[

3].

Faced with the significant increase in the population aged over 60, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the World Report on Ageing and Health in 2015, reformulating and reorienting global actions aimed at healthy ageing [

4]. Aging healthily involves maintaining and developing functional capacity and intrinsic capacity, promoting well-being in old age, even in the presence of diseases [

5]. The concept of Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) then emerged, focusing on maintaining the skills and abilities of the elderly and not just on the losses/illnesses of aging [

6,

7].

Intrinsic capacity (IC) was defined as the set of physical and mental capacities that a person can use throughout their life and its construct was developed based on five essential, but not unique, domains: cognitive, psychological, locomotor, vitality and sensory[

8]. Through the CI and its domains, it is possible to carry out monitoring that is contextualized with the specificities of the individual and the population analyzed, as well as to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions already carried out or to indicate interventions that are needed in the short term (red flags) [

9,

10]. One of ICOPE’s ideas is longitudinal screening of the IC domains, checking whether the person is out of expectations and thus with time for correction.

Despite being a valuable and person-centered instrument and efforts being made to implement it in several countries, there is little evidence on the clinical usefulness of the ICOPE tool [

11,

12], requiring validation studies of the instrument and studies how to incorporate it into care models [

13]. In addition, evidence on its feasibility, diagnostic accuracy, psychometric characteristics and real utility is still scarce.

The WHO points out that intrinsic capacity is expected to decrease with age, suggesting the importance of its assessment by age group. Furthermore, it seems clear that, as opposed to evaluating the construct as a Whole [

11,

12,

14,

15], it is better to evaluate each domain separately [

13,

16], so that possible interventions/monitoring are individualized for each domain.

Therefore, the objective of the study was to evaluate the performance of diagnostic measures (sensitivity and specificity) of the intrinsic capacity construct recommended by the WHO ICOPE guidelines by domain and by age group.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

It was a cross-sectional study, with a convenience sample that included 164 elderly people, living in the coverage area of two Family Health Units (USFs in Portuguese acronym) in the city of Marília, São Paulo, Brazil. The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Faculty of Philosophy and Sciences-Unesp/Marília (protocol no. 4,168,934). The eligibility criteria were: ≥ 60 years old, not having diagnosed dementia, not having acute heart failure, infection, cerebrovascular disease, severe cardiac, hepatic or renal dysfunction, Parkinson’s disease, blindness and deafness. A search of individuals aged 60 years or over who were registered with the USFs was performed through the e-SUS Primary Care digital platform. Next, the assessment was scheduled in two ways: (1) the older adults were contacted by telephone and invited to come to the USF to participate in the study; (2) community agents of the USFs visited the homes of the older adults and performed the assessments on those who agreed to participate.

2.2. Assessments

2.2.1. Primary Outcomes

Intrinsic Capacity

Cognitive domain: the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) was used to assess the participants’ cognitive domain. The total test score is 30 points and normality scores vary according to the level of education [

17].

Psychological Domain: the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) was used to analyze the psychological domain. Its advantages include easy-to-understand questions, small variation in the possible answers (yes/no), and self-administration or administration by an interviewer. The score ranges from 0 (absence of depressive symptoms) to 15 points (maximum score of depressive symptoms).

Vitality Domain: the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), a tool recommended by the WHO [

18], was used to assess this domain, with scores ranging from 0 to 14: ≥12 indicates a satisfactory nutritional status; between 8 and 11 indicates a risk of malnutrition; and a score <8 indicates malnutrition [

19].

Locomotion Domain: Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). The SPPB is a tool for assessing lower limb function through a battery of static balance tests, gait speed and the test of getting up from a chair five consecutive times (lower limb strength). Each test can be evaluated separately or together, generating a total score of 0 (worst performance) to 12 points (best performance) [

20].

Sensory Domain: hearing and visual impairments were assessed using a self-report with previously validated questions [

21,

22]. Hearing status was assessed by asking participants to rate their hearing as excellent, very good, good, fair or poor (with the help of a hearing aid, if they wore one). For vision, participants were also asked “how good is your vision for seeing things at a distance, such as recognizing a friend across the street” and “how good is your vision for seeing things up close, such as reading a newspaper”, categorizing the answer options as excellent, very good, good, fair or poor. This assessment was made with the participant wearing glasses or corrective lenses, if they normally did so. For each answer given in relation to hearing and vision, a score was assigned according to the Likert scale: 1 - poor, 2 - fair, 3 - good, 4 - very good and 5 - excellent. An average was taken of the three assessments (far vision, near vision and hearing) to determine the scores for this domain.

2.2.2. Secondary OutcomesLevel of Dependence

The level of dependence can interfere with the domains of intrinsic capacity. For this reason, activity of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) were also assessed. The Barthel Index was used to assess ADL and the Lawton scale for IADL.

Urinary Incontinence

Urinary incontinence (UI), defined as any involuntary loss of urine [

23], can negatively impact lifestyle, limiting daily and social activities. As UI is considered a geriatric syndrome [

24]and can also interfere in the domains of intrinsic capacity, complaints related to urinary incontinence were assessed using the ICIC-SF.

Frailty

Frailty is the result of organic deficiencies, which generate alterations in the healthy ageing process. Research has shown that the level of frailty can improve or worsen over time [

25,

26]. In this study, frailty was assessed using the Edmonton Frail Scale (EFS)[

27].

2.2.3. Other evaluations

The following variables were considered in the possible explanation of the outcomes: age, gender, schooling and housing conditions.

3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the intrinsic capacity and identify which domains were compromised. Comparisons between three or more samples were made by 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test and those with two samples by the t-test or Mann-Whitney test for quantitative variables. Chi-square test was used for qualitative variables.

Each domain of intrinsic capacity received a score of zero when it was in disagreement with the reference values of the tests applied: Cognitive domain (MOCA): according to education (illiterate: ≤ 11; 1 to 4 years of study: ≤16; 5 to 11 years of study: ≤19; ≥ 12 years of study: ≤ 25) [

20]; locomotion domain (SPPB) ≤ 9; psychological domain: >5; vitality domain (MNA) ≤ 11; sensory domain: ≤ 2 (Likert scale ranging from 0 to 5).

The total intrinsic capacity score ranged from zero to five, with higher scores indicating better intrinsic capacity. Values between zero and two were indicated as having a decline and values between three and five as not having a decline.

The sensitivity and specificity of each domain and each domain by age group were evaluated using the ROC curve. A screening tool is considered to have good performance if sensitivity and specificity are > 80%; reasonable performance, if sensitivity or specificity are < 80%, but both values > 50%; and poor performance if sensitivity or specificity is < 50%. In addition, the Youden index was also used, which summarizes the sensitivity and specificity of a tool. A Youden index of 1 indicates perfect sensitivity and specificity, and a value of 0 indicates that the test is not useful.

3. Results

The mean IC score was 2.73±1.33. Of the total number of participants, only 17 (10.4%) were categorized as not having declined in any domain. On the other hand, of the 164 elderly people included, 40 (24.4%), 43 (26.2%), 41 (25%), 18 (11%) and 5 (3%) showed a decline in one, two, three , four or five domains, respectively. The percentage of people with decline in each domain was: cognitive: 40.8%; psychological: 9.7%; vitality: 43.3%; locomotor: 63.4%, sensory: 53.6%.

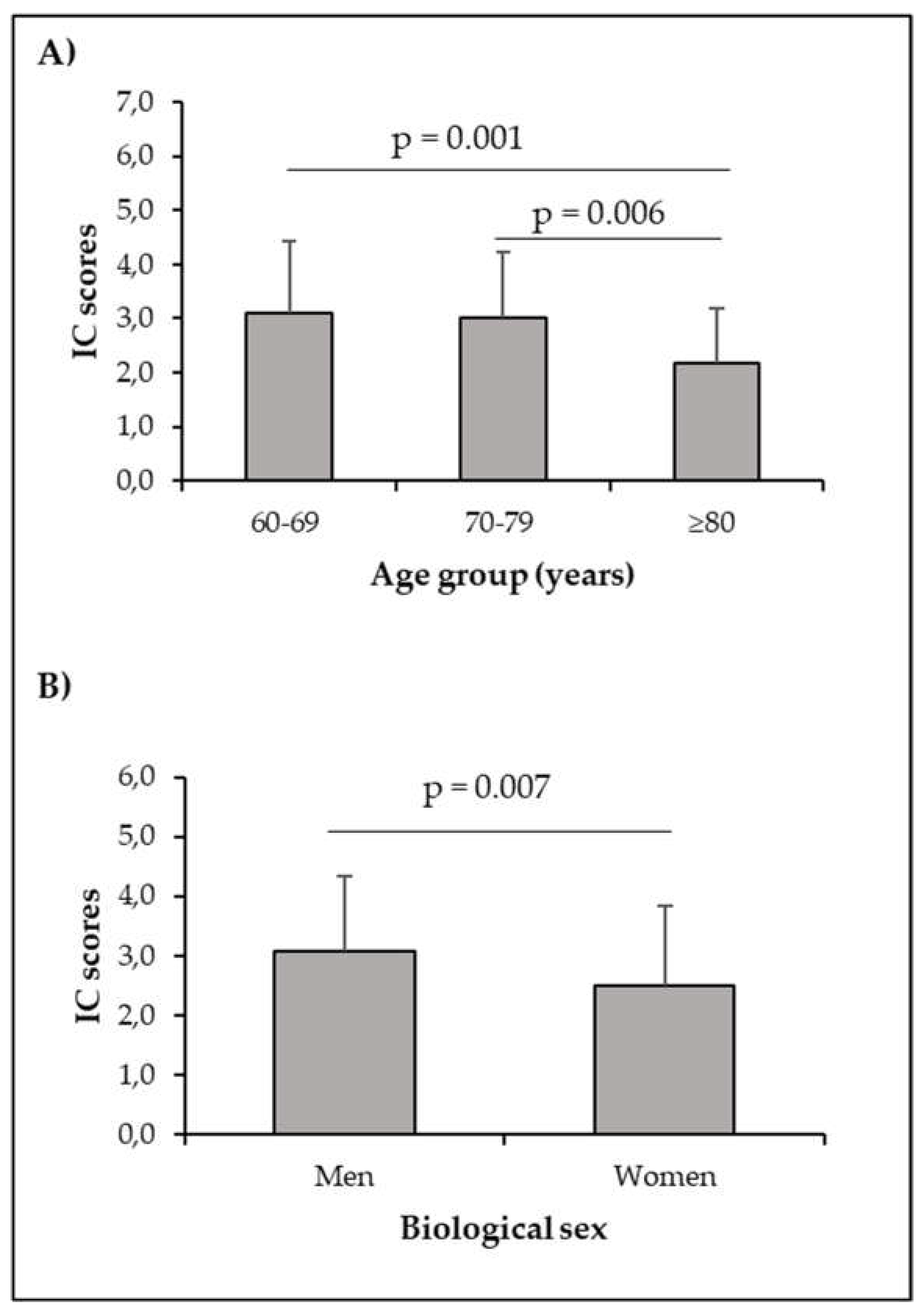

Our data showed an effect of age on IC scores [(2.0.161) = 6.574; p = 0.002], reinforcing the importance of its assessment in all age groups. There was also a difference between men and women (3.1±1.26 and 2.5±1.35, respectively).

Figure 1 shows comparisons of IC scores by age group and biological sex.

3.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

As shown in

Table 1, participants with declines in IC were older, worse ADL function and low gait speed. They had worse mental function indicated by lower MoCa scores and had higher GDS scores. In addition, people with a decline in IC had frailty, urinary incontinence and worse IADL activities. Other issues related to the decline in CI were self-reported non-practice of physical activities and level of schooling.

Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation or n (%); DIC: decline in intrinsic capacity; Non-DIC: no decline in intrinsic capacity; MoCa: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale. IADL: instrumental activity of daily living; ADL: activity of daily living; m/s: metes per second. * adjusted by schooling

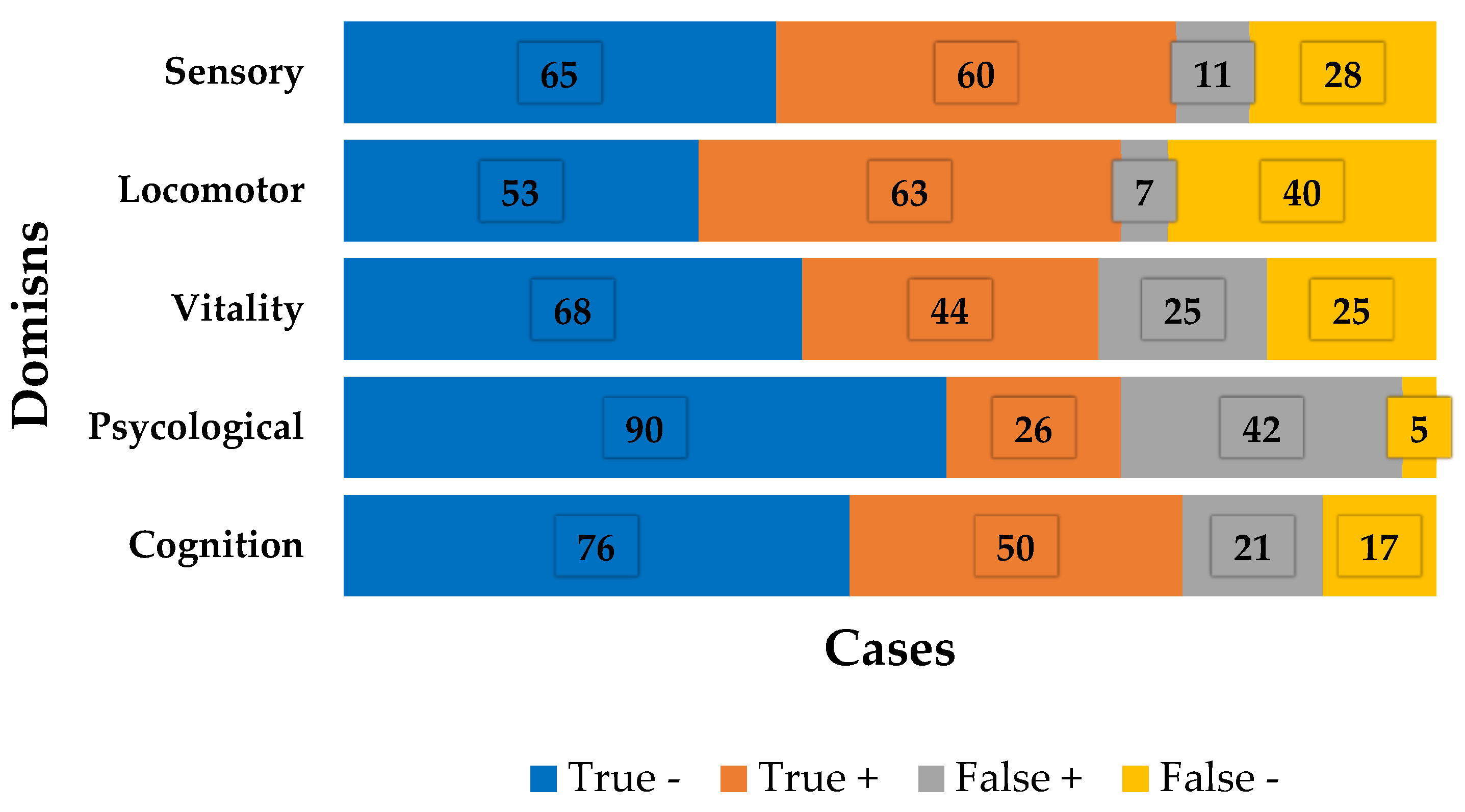

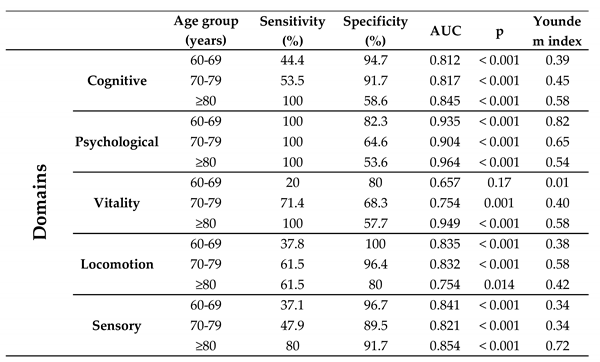

Table 2 shows the ROC curve and Youden index values for the domains separately, while

Figure 2 shows the distribution of cases in each domain.

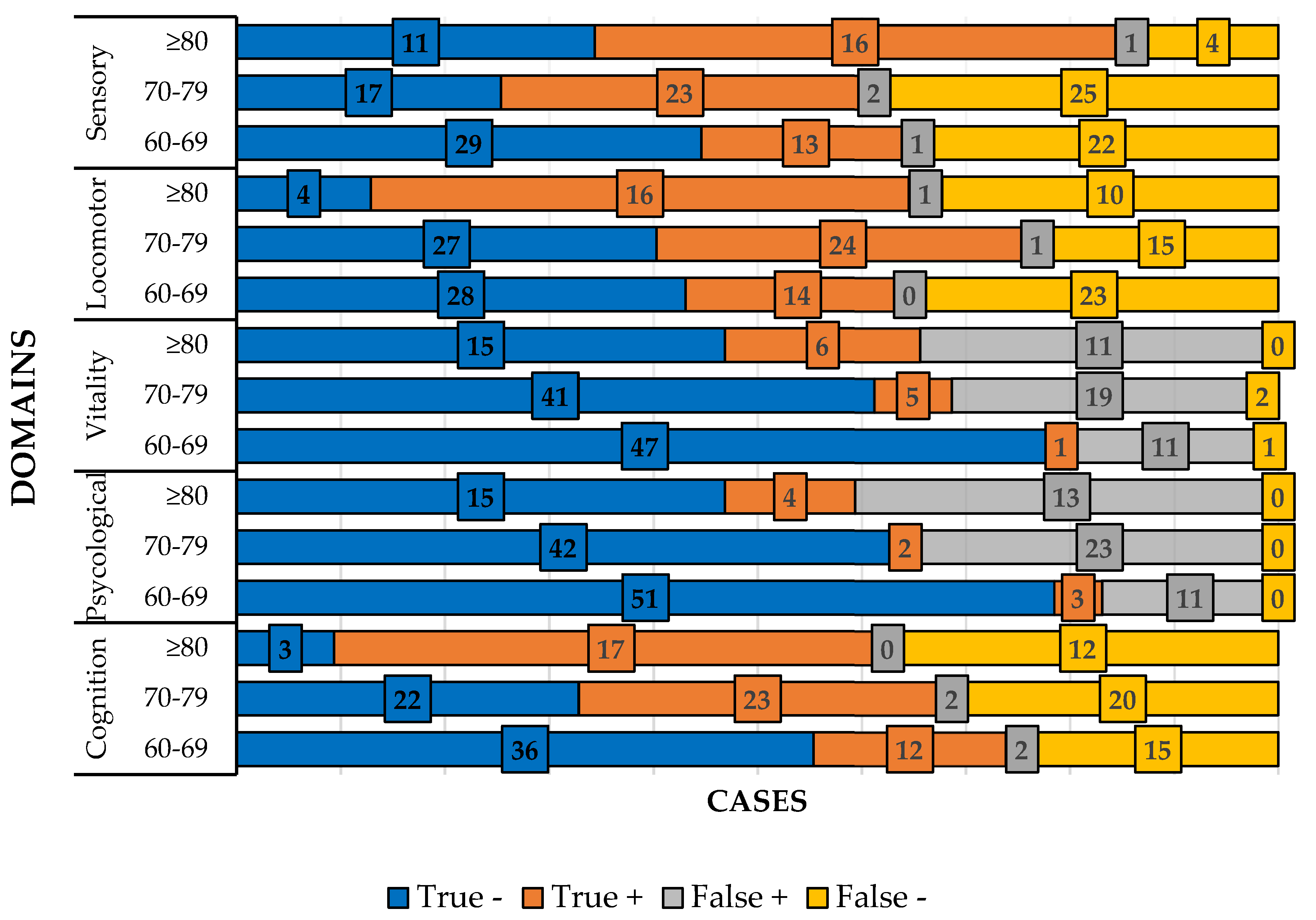

Table 3 shows the ROC curve and Youden index values for each domain by age group and

Figure 3 shows the absolute frequency in each domain by age group.

4. Discussion

The population is getting older in an unprecedented phenomenon in the history of humanity. Because of this, the WHO launched in 2017 a person-centered care model called Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE), based on functional ability and intrinsic capacity. Through the construct of intrinsic capacity, it is possible not only to indicate necessary treatments, but also to prevent diseases from occurring. Despite the importance of the subject, there is little evidence of the validity of this construct in the literature [

13].

Our results showed that in the population studied, 89.6% of people showed one or more declines in IC, a percentage above that found in other studies [

11,

12] and close to the research carried out by Tavassoli et al. - 94.3% [

28]. As in other research, our data also showed a decline in IC with advancing age, in line with the intrinsic capacity model formulated by the WHO [

8,

11,

12].

Another finding was that men had higher IC scores than women (

Figure 1). However, the fact of being a woman or a man is not implicated in the development of IC decline (

Table 1). The comparisons made between the groups showed that the older people who had a decline in intrinsic capacity performed worse in postural balance, cognition and psychological aspects. This indicates that these people are not aging healthily.

Frailty is defined as an age-related, multi-causal syndrome that negatively affects the homeostatic reserves of the elderly, predisposing them to a high risk of negative outcomes [

29]. Our data, such as in another studys [

12], showed that elderly people with decline in IC, are more prone to developing frailty. A longitudinal study by Liu et al. [

30] followed the trajectory of IC and frailty in elderly people living in the community and concluded that IC impairment and frailty overlap and coexist in older adults, and that it is important to observe both issues in order to detect early declines in intrinsic capacity and/or the presence of frailty. In another study, Belloni and Cesari stated that intrinsic capacity and frailty have similarities and peculiar points and that the IC construct can be considered as a sort of evolution of frailty, in the sense that we have to look at the capacities that are still preserved and not just the losses [

29]. However, there is another issue to discuss. Is an elderly person with a decline in intrinsic capacity more likely to develop frailty or does being a frail elderly person cause them to have a decline in intrinsic capacity? Where does each syndrome start? In fact, the health of the older person should be monitored at all times and not just when they have disabilities.

Regarding diagnostic measures, when the assessment was made in relation to each domain, none of them proved to be a good screening tool (sensitivity and specificity >80%), but all of them can be classified as a reasonable screening tool (sensitivity or specificity < 80%, but both values > 50%). The Youden index also performed reasonably well.

When the analyses were separated by domain and age group, good performance was found in the psychological (69-69 years and ≥80 years), vitality (≥80 years) and sensory (≥80 years) domains. For the other domains and age groups, performance was reasonable. These results reinforce the idea that evaluation by domain is better than with all the domains together and adds a new fact that the age group must be taken into account in each domain to be evaluated. Of the five domains assessed, the ≥80 age group performed well in three of them and reasonable in two.

Only one study validating intrinsic capacity with the Brazilian population was found. [

31]. This study concluded that the IC construct is valid and reliable for assessing healthy ageing in diverse socioeconomic and cultural settings. Our data showed that it is possible to apply the IC construct in the evaluation of the elderly population, with good sensitivity and specificity, but it should be noted that the evaluation should be separated by domain and by age group.

The IC construct proposed by WHO should be used as a screening tool for the assess presence/decrease/absence of capabilities. With this screening, it is possible to determine the individuals most at risk of developing/having alterations (red flags) and those who can be monitored over time. For red flags, it will be possible to determine better treatments and the responses to them. Our data showed that the majority of the population evaluated had one or more domains with decline. This means that urgent action is needed to ensure that these elderly people do not experience a deterioration in their abilities, but have the possibility of healthy ageing.

5. Conclusions

The ICOPE screening tool performed well in terms of diagnostic measures when applied by domain and age group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.S.; methodology, M.E.S.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, T.G.C.C., L.M.N., J.F.L.S, L.P.S, B.B.I.; L.M.N. and M.E.S., X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, M.E..S; writing—review and editing, M.E.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Philosophy and Sciences-Unesp/Marília (protocol no. 4,168,934, approved on July 22, 2020 ).” for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- World Health Organization, Ageing, (2021). https://www.who.int/health-topics/ageing#tab=tab_2 (accessed May 17, 2021).

- World Health Organization, Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health and ageing, (2023). https://platform.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-ageing/indicator-explorer-new/mca/number-of-persons-aged-over-60-years-or-over-(thousands) (accessed May 22, 2023).

- Tesouro Nacional, Relatório de Riscos Fiscais da União, Brasília, 2019.

- WHO, Integrated care for older people Guidelines on community-level interventions to manage declines in intrinsic capacity, Integrated Care for Older People: Guidelines on Community-Level Interventions to Manage Declines in Intrinsic Capacity (2017) 7–9. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/258981%0Ahttps://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258981/9789241550109-eng.pdf;jsessionid=C5CA4C995E986DC931F1F97A0CB7EED4?sequence=1.

- Beard, J.R.; Officer, A.; de Carvalho, I.A.; Sadana, R.; Pot, A.M.; Michel, J.-P.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; Epping-Jordan, J.E.; Peeters, G.M.E.E.G.; Mahanani, W.R.; et al. The World report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sum, G.; Lau, L.K.; Jabbar, K.A.; Lun, P.; George, P.P.; Munro, Y.L.; Ding, Y.Y. The World Health Organization (WHO) Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) Framework: A Narrative Review on Its Adoption Worldwide and Lessons Learnt. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization, Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE): Guidance for Person-Centred Assessment and Pathways in Primary Care., Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-FWC-ALC-19.1.

- Cesari, M.; De Carvalho, I.A.; Thiyagarajan, J.A.; Cooper, C.; Martin, F.C.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Vellas, B.; Beard, J.R. Evidence for the Domains Supporting the Construct of Intrinsic Capacity. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Boil. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 1653–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althoff, T.; Sosič, R.; Hicks, J.L.; King, A.C.; Delp, S.L.; Leskovec, J. Large-scale physical activity data reveal worldwide activity inequality. Nature 2018, 547, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, L.M.D.; da Cruz, T.G.C.; Silva, J.F.d.L.e.; Silva, L.P.; Inácio, B.B.; Sadamitsu, C.M.O.; Scheicher, M.E. Use of Intrinsic Capacity Domains as a Screening Tool in Public Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, A.Y.M.; Su, J.J.; Lee, E.S.H.; Fung, J.T.S.; Molassiotis, A. Intrinsic capacity of older people in the community using WHO Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) framework: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Chhetri, J.K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Chan, P. Integrated Care for Older People Screening Tool for Measuring Intrinsic Capacity: Preliminary Findings From ICOPE Pilot in China. Front. Med. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, V.P.; Ferriolli, E.; Lourenço, R.A.; González-Bautista, E.; Barreto, P.d.S.; de Mello, R.G.B. The sensitivity and specificity of the WHO's ICOPE screening tool, and the prevalence of loss of intrinsic capacity in older adults: A scoping review. Maturitas 2023, 177, 107818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.-C.; Huang, S.-T.; Peng, L.-N.; Chen, L.-K.; Hsiao, F.-Y. Biological Features of the Outcome-Based Intrinsic Capacity Composite Scores From a Population-Based Cohort Study: Pas de Deux of Biological and Functional Aging. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 851882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- i Luque, X.R.; Blancafort-Alias, S.; Casanovas, S.P.; Forné, S.; Vergara, N.M.; Povill, P.F.; Royo, M.V.; Serrano, R.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, D.; Saldaña, M.V.; et al. Identification of decreased intrinsic capacity: Performance of diagnostic measures of the ICOPE Screening tool in community dwelling older people in the VIMCI study. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Integrated care for older people: Guidelines on community-level interventions to manage declines in intrinsic capacity, in: Geneva, 2017: pp. 7–9.

- Smid, J.; Studart-Neto, A.; César-Freitas, K.G.; Dourado, M.C.N.; Kochhann, R.; Barbosa, B.J.A.P.; Schilling, L.P.; Balthazar, M.L.F.; Frota, N.A.F.; de Souza, L.C.; et al. Declínio cognitivo subjetivo, comprometimento cognitivo leve e demência - diagnóstico sindrômico: recomendações do Departamento Científico de Neurologia Cognitiva e do Envelhecimento da Academia Brasileira de Neurologia. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2022, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I.Araujo De Carvalho, C. I.Araujo De Carvalho, C. Martin, M. Cesari, Y. Sumi, J.A. Thiyagarajan, J.R. Beard, Operationalising the concept of intrinsic capacity in clinical settings, WHO Clinical Consortium on Healthy Ageing (2017) 31. https://www.who.int/ageing/health-systems/clinical-consortium/CCHA2017-backgroundpaper-1.pdf.

- Kaiser, M.J.; Bauer, J.M.; Ramsch, C.; Uter, W.; Guigoz, Y.; Cederholm, T.; Thomas, D.R.; Anthony, P.; Charlton, K.E.; Maggio, M.; et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short-Form (MNA®-SF): A practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.M. Nakano, M.J.De. M.M. Nakano, M.J.De. Diogo, W.J. Filho, Versão brasileira da Short Physical Performance Battery - SPPB: adaptação cultural e estudo da confiabilidade, Universidade Estadual de Campinas; 2007.

- Ferrite, S.; Santana, V.S.; Marshall, S.W. Validity of self-reported hearing loss in adults: performance of three single questions. Rev. de Saude publica 2011, 45, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimdars, A.; Nazroo, J.; Gjonça, E. The circumstances of older people in England with self-reported visual impairment: A secondary analysis of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). Br. J. Vis. Impair. 2012, 30, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, P.; Cardozo, L.; Fall, M.; Griffiths, D.; Rosier, P.; Ulmsten, U.; Van Kerrebroeck, P.; Victor, A.; Wein, A. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology 2003, 61, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Shin, J.; Choi, J.; Park, J.-M.; Park, H.K.; Lee, J.; Han, S.-H. Association of Geriatric Syndromes with Urinary Incontinence according to Sex and Urinary-Incontinence–Related Quality of Life in Older Inpatients: A Cross-Sectional Study of an Acute Care Hospital. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2019, 40, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Nofuji, Y.; Seino, S.; Murayama, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Tanigaki, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Narita, M.; Nishi, M.; Kitamura, A.; et al. Healthy lifestyle behaviors and transitions in frailty status among independent community-dwelling older adults: The Yabu cohort study. Maturitas 2020, 136, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.P.; Feng, L.; Nyunt, M.S.Z.; Feng, L.; Niti, M.; Tan, B.Y.; Chan, G.; Khoo, S.A.; Chan, S.M.; Yap, P.; et al. Nutritional, Physical, Cognitive, and Combination Interventions and Frailty Reversal Among Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Med. 2015, 128, 1225–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabrício-Wehbe, S.C.C.; Schiaveto, F.V.; Vendrusculo, T.R.P.; Haas, V.J.; Dantas, R.A.S.; Rodrigues, R.A.P. Cross-cultural adaptation and validity of the "Edmonton Frail Scale - EFS" in a Brazilian elderly sample. Rev. Latino-Americana de Enferm. 2009, 17, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, N.; Barreto, P.d.S.; Berbon, C.; Mathieu, C.; de Kerimel, J.; Lafont, C.; Takeda, C.; Carrie, I.; Piau, A.; Jouffrey, T.; et al. Implementation of the WHO integrated care for older people (ICOPE) programme in clinical practice: a prospective study. Lancet Heal. Longev. 2022, 3, e394–e404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, G.; Cesari, M. Frailty and Intrinsic Capacity: Two Distinct but Related Constructs. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Kang, L.; Liu, X.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, S. Trajectory and Correlation of Intrinsic Capacity and Frailty in a Beijing Elderly Community. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 751586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliberti, M.J.; Bertola, L.; Szlejf, C.; Oliveira, D.; Piovezan, R.D.; Cesari, M.; de Andrade, F.B.; Lima-Costa, M.F.; Perracini, M.R.; Ferri, C.P.; et al. Validating intrinsic capacity to measure healthy aging in an upper middle-income country: Findings from the ELSI-Brazil. Lancet Reg. Heal. - Am. 2022, 12, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).