1. Introduction

Lao PDR is a member of ASEAN since 1997 and has adopted the ASEAN CBT Standard in 2016. Before outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism was rapidly growing in Laos [

1]. In 2019, international tourist arrivals increased by 14.4%, reaching 4.79 million. International tourism receipts totaled

$934 million. During the years 2010-2019, international tourism receipts increased faster than international arrivals, suggesting increased sector value. Accordingly, it has been estimated that tourism directly contributes to 4.6% of GDP of the country [

2]. In 2019, the highest number of international tourists to Laos accounted for more than 2.1 million (45.0% of the total) arrivals from Thailand, followed by the People’s Republic of China with more than 1 million (21.3%), Viet Nam with 0.92 million (19.3%), and the Republic of Korea with 0.2 million (4.2%). Owing to the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Visa Exemption that allows ASEAN nationals to travel Laos without visa for 14-30 days, more than 3.1 million arrived from ASEAN accounting for two-thirds of all international visitors to Laos [

3].

Meanwhile, in the literature there has been rather a scarcity of efforts to assess the ASEAN CBT Standard compared to other formidable tourism industry-related standards. As such, it would be meaningful to examine the implementation ASEAN CBT Standard for individual ASEAN member states. In this regard, Laos constitutes a unique case among the 10 ASEAN member states as it has the most successful community-based ecotourism model that tracks back to 1999, considerably before adoption of the ASEAN CBT Standard in 2016. This implies that Laos has significant potential to become a growing community-based tourism destination, with its rich experiences of working with diverse international partners for technical assistance and public sectors who learned from the existing models, as well as the private sector who demonstrated the ways for income generation for the community [

4].

Furthermore, limited investigations are ongoing on how to customize and/or localize the ASEAN CBT Standard by taking into consideration the unique environments and circumstances of each ASEAN member state, leaving much to be desired about knowledge on enhancing the chance of successful implementation. While there are few reviews about the voices of general CBT stakeholders in implementing the ASEAN CBT Standard, these are at a rather general level and implications for the policymakers, who are usually high-ranking officials, remain insubstantial [

5].

To this end, this study utilizes series of in-depth interviews with the executive-level stakeholders of ecotourism development in Laos that represent the government, the international organization, and the private sector. This approach is crucial in that it enables a holistic view of the tourism development in Laos, which has evolved from partnerships among stakeholders leading community-based tourism projects. In addition, interview with former specialist in international organization dedicated to ASEAN tourism development is utilized to allow the ASEAN perspective in examining the case of Laos in facilitating and coordinating CBT operation, evaluation, and even review mechanisms.

Accordingly, three research objectives were set forth to fulfill the purpose of research, which is the investigate the issues in implementing ASEAN CBT Standard in the tourism industry of Laos, through in-depth semi-structured interviews with seven high-ranking experts in Lao CBT tourism sector: 1) identify the application of ASEAN CBT standard and its assessment in Laos, 2) examine the role of key CBT stakeholders including the current CBT partnership in Lao PDR, and 3) analyze the key aspects of CBT success and to identify the major challenges associated with operating successful CBT.

2. Literature Review

2.1. CBT Operation in Laos

After first opening the border for international tourists in 1989, Laos published the first National Tourism Development Plan in the following year. Moving on, the second National Tourism Development Plan in 1998 targeted conventional sightseers, special interest tourists, and cross border and domestic tourists. Under the second national plan, Laos initiated a major tourism development project, the Nam Ha Ecotourism Project (NHEP), which eventually became the model for all future CBT ecotourism projects of the province, in Luang Namtha Province in 1999. The project was co-funded by the Government of New Zealand through the New Zealand Overseas Development Agency and the Government of Japan through the International Finance Corporation, while additional technical assistance was provided by UNESCO [

4,

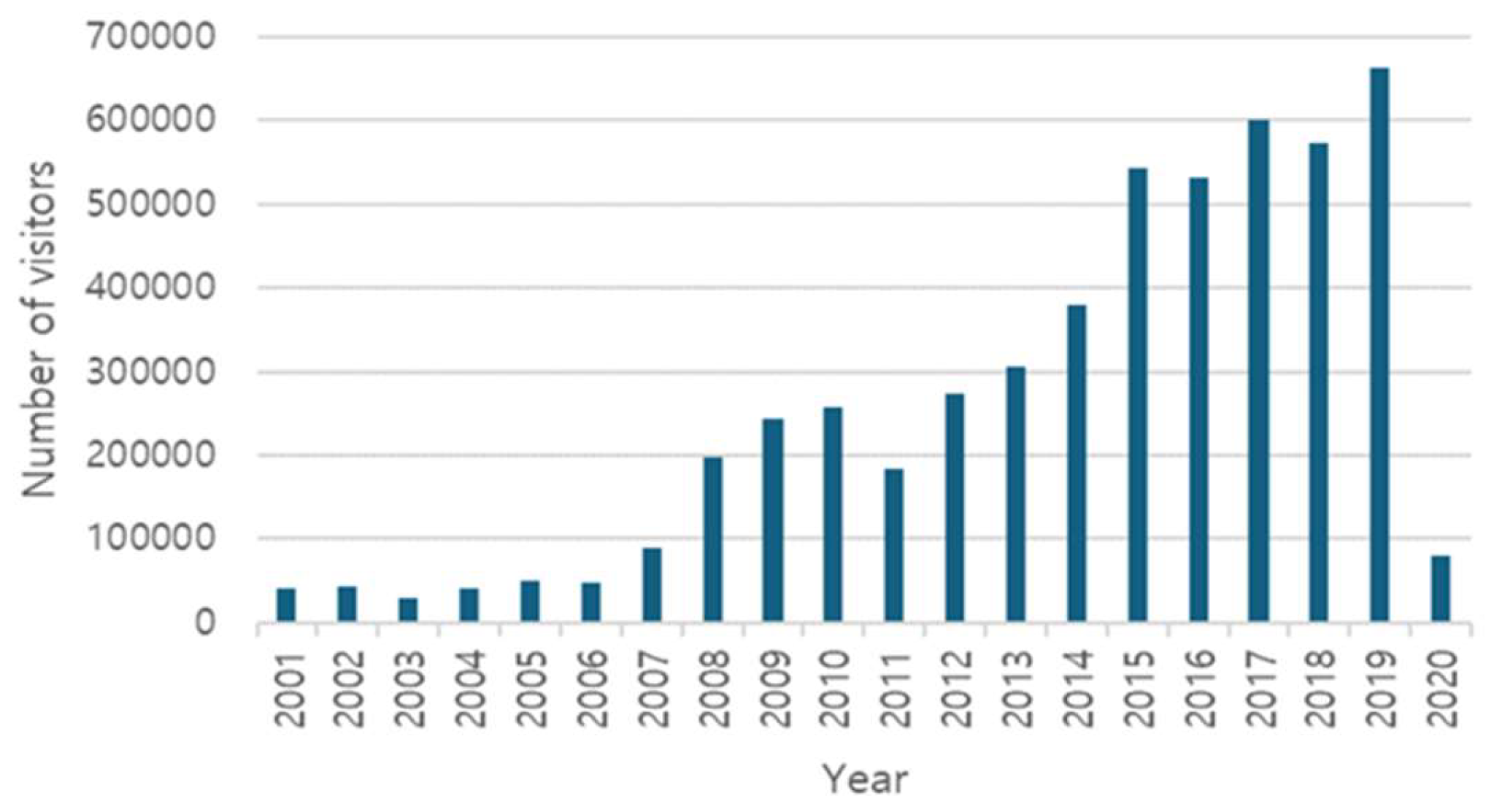

6]. Through NHEP, according to Luang Namtha Provincial Tourism Department, the number of tourists to Luang Namtha increased from 4,732 in 1995 to 24,700 in 2000. A more recent trend of the visitor statistic is shown in

Figure 1.

According to an exploratory survey in 1999, the international visitors were interested in overnight treks with trained guides to the Nam Ha National Protected Areas and guided river trips to the protected areas [

7]. The main reason international visitors come to the Luang Namtha province is to appreciate its outstanding natural and cultural landscape. Community income increased through economic opportunities created by provision of food, lodging, and handicraft sales, which in turn, promoted income distribution among the villagers. NHEP devised a manual for guide training as well as developed a monitoring system to track the numbers of visitors and carrying capacity, in attempt to assess the impact of the treks in the communities [

6]. NHEP was recognized as the ‘best practice’ of ecotourism projects by the United Nations in 2001 and by British Airways in 2002 for its contribution to poverty reduction [

7]. Borrowing from the successful NHEP model, the Asian Development Bank implemented the Mekong Tourism Development Project (MTDP) from 2003 to 2007 in four provinces of Laos with ten to twelve CBT sites, aiming to enhance private sector partnerships and competitiveness of developed CBT sites. In 2016, Laos adopted the ASEAN CBT Standard followed by the adoption of Laos CBT Standard in 2-23. Serving as a continuation of the MTDP, the Sustainable Tourism Development Project (STDP) in 2009 targeted nine provinces [

8]. The Development history of CBT partnerships in Laos is summarized in

Table 1 and the current list of CBTs in Laos in

Table 2.

2.2. Implementation of CBT Standard in the ASEAN

The Thai CBT Standard handbook developed by the Thailand Community-based Tourism Institute (CBT-I) in 2013 consists of 5 pillars, namely, (1) sustainability tourism management for CBT, (2) distribution of benefits to the local area and society and improvement of quality of life, (3) celebration, conservation and support of cultural heritage, (4) systematic, sustainable natural resources and environmental management and (5) CBT service and safety with 29 criteria and 176 indicators. The handbook is written based on the feedback from communities as well as related stakeholders in Thailand and in Europe. This standard encouraged community members to set the developmental direction and to monitor and assess the progress of local CBT development by collecting information in a systemic fashion. In addition, the result of assessment for each criterion is useful information for planning for future development, as the checklist can assist communities to prepare for the market [

9]. However, criticisms exist in that the CBT-I Standard remains to be a self-assessment tool and a guide rather than a certification with responsibilities. Additional critiques follow regarding some of the indicators being ambiguous and lacking quantifiable measurement schemes [

10].

In 2016, the ASEAN CBT Standard adopted by ten ASEAN member states was initially intended to provide direction to communities on quality of services for tourists at a consistent level across the ASEAN. Evaluation of the quality is enabled by the checklist, which consists of eight criteria, 23 sub-criteria, and 171 indicators. Out of the 171 indicators, 89 indicators are for minimum requirements, 52 are for advanced requirements, and 30 are for best practice requirements. For certification, the CBT initiative needs to fully comply with at least 70% of the relevant minimum requirements and 60% of the advanced requirements of the indicators in

Table 3. The checklist can also function as a tool to self-administer and identify weaknesses in the current tourist services and offerings. The assessment is conducted in an evidence-based manner through documents, observations and interviews, and photographs. The handbooks, checklists, codes-of conduct, and community audit workbooks of ASEAN CBT Standard are accordingly provided to the community [

11].

2.3. CBT Partnership in Laos

Pio [

12] suggested that there are three types of CBT partnerships in the Lao context: 1) Donor-assisted Partnership, 2) CBT Public-Private Partnerships (CBT PPP), and 3) Inclusive business model. The first type, Donor-Assisted Partnership, brings development agencies, communities, central and local governments, and the private sector together. The partnership model prioritizes benefits of the community in short- and long-term periods and benefit distribution systems such as village funds. This partnership model originated from the NHEP began in 1999, where the private sector was involved in selling and administering the products through partnership agreements. However, disruption in the funding cycle of international development agencies, which frequently leads to interrupted involvement of the agency, may prevent the smooth cooperation among stakeholders.

The second type of CBT partnership, PPP, is developed by the private sector and focuses the size of economic benefits rather than its distribution amongst the community. In Lao context, CBT PPP usually involves tour operators that have previous experience in CBT projects. As Laos tend to have less capacity in facilitating the establishment of PPP, there exist not many such partnerships. Community-private sector joint venture was defined by Ashley & Jones [

13] as a contractual partnership between a community and a private investor where they work together in establishing single tourism venture. They posit that lessons can be learned from successful joint venture partnerships although it is highly unlikely any joint venture can be easily replicable. One of the lessons from Ashley & Jones [

13] is that national policy and legislation should play an enabling role in the process. In Laos, cases have been reported in which the lag time between development and sales of the products led to disinterest of the community and the private sector in joint ventures. Furthermore, transparent and effective PPP should be established to reduce poverty by developing local skills of the community, such as the Konglor Cave located in Khammouane Province that won the ASEAN CBT Standard Award.

An example of the third type is exemplified by the Lao government investing in road access and basic tourism amenities, and the community reaching an agreement with the government to manage the site. For example, the Tree-top Explorer ziplining and trekking program at Nong Louang village well represents the inclusive business model owned by a leading private entity in ecotourism. It is often considered that inclusive business model is the fastest growing model and instigates improved access and regulations in Laos [

12].

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

A qualitative approach is deemed suitable for this study, due to the complexity of CBT dynamics and the necessity to draw on the CBT experts’ experiences, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors [

10]. To carry this out, in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted to collect information from the interview participants [

14]. The semi-structured interviews contained a list of questions developed from the literature on CBT. Questions were organized to solicit answers on the recent CBT projects that the interviewees were involved in, issues related to the ASEAN CBT Standard, the level of awareness on ASEAN CBT Standard among different stakeholders, the contribution of CBT to Lao tourism industry, and finally, positive and negative impacts of the CBT.

This research adopted a content analysis approach to analyze of the data. According to Weber [

15], content analysis utilizes a set of procedures to make valid inferences from texts. It is applied in a diversity of disciplines to analyze various forms of communication by utilizing textual data, while Stepchenkova [

16] notes that a growing number of tourism studies utilize qualitative data such as interviews and open-ended questions. Gray and Densten [

17] state that content analysis extracts patterns and structures, draws out key features to which researchers want to pay attention, develops categories, and combines them into perceptible constructs in order to seize the meaning of the textual data. Therefore, it can be considered a systemic process to extract valid implications from the data of qualitative nature.

Based on Simpson’s [

18] identification of key stakeholders of CBT, the executive interviewees were recruited from the Ministry of Information, Culture, and Tourism(MICT) of Laos, the Provincial Tourism Department of Laos, international developmental partners, and the private sector. The interviewees were chosen for their high-level experience in decision making and management in development and implementation of CBT partnerships in Laos and in designing the assessment of tourism standard in ASEAN.

3.2. In-Depth Interview Design and Data Analysis

The interviews were designed accordingly to the main research aim and objectives. Also, during the interviews, critical issues and responses were noted, and followed-up through additional pertinent questions. Due to the COVID-19 situation, interviews were conducted via online video meetings. All respondents were given written information beforehand about the research objectives so that they can fully understand their role in the in-depth interviews. This also gave interviewees the time to prepare their responses in advance for the actual meeting. All participants gave informed verbal and recorded consent for the data collection and recording. Respondents were coded (RP1-RP7) so that their anonymity is guaranteed. As summarized in

Table 4, the interviews lasted from 30 to 70 minutes, depending on the complexity of the topics interviewed. All interviews were conducted in the English language.

3.3. Data Analysis

After the in-depth interviews with seven experts were conducted, the recorded responses were coded and summarized. Drafts of the summary were sent to each interviewee for confirmation and validation of their answers, so that there is no misinterpretation. The framework shown in

Table 5 was utilized to facilitate the analysis derived from the data extracted from the interviewee responses; it is noteworthy that these portray the concern and views on the ASEAN CBT Standard implementation in Laos.

Also through content analysis of the data, categories were developed and classified into the following themes: the ASEAN CBT Standard and Awards, independent review mechanism, localization of ASEAN CBT Standard, partnership between the private sector and the community, lack of demand for recognition, and multilateral stakeholder collaboration efforts. These perceptual constructs were used to facilitate comprehension of the responses [

16].

4. Results

Major findings are discussed in the following subsections, including limitations and positive aspects of the current ASEAN CBT Standard when applied to the general context of Laos. The Standard requires communal understanding of respective stakeholders in order to operate cohesively. That is, a multilateral stakeholder collaboration is a necessary condition that most interviewees emphasized. The gap between the supply and demand sides for CBT products remains a fundamental issue.

4.1. The ASEAN CBT Standard and Awards

At the 20th meeting of ASEAN Tourism Ministers in Singapore held in January 2017, the Ministers presented the first ASEAN CBT Awards to 26 recipients from 10 ASEAN Member States. According to the Joint Media Statement of the meeting [

19], the Award is based on the ASEAN CBT Standard comprised of umbrella performance indicators for the coordinated management of tourism products offered by communities under the organization of a CBT Committee. The ASEAN CBT Standard was used to create a checklist of the performance standards, which consists of 8 criteria, 23 sub-criteria and 171 indicators, categorized into minimum, advanced, and best practice requirements. For self-assessment, the communities are provided with standard handbooks, checklist, codes-of-conduct and community audit workbooks in the form of evidence of documents, observations, interviews and photographs [

11].

There exist two types of recognition related with the ASEAN CBT Standards: certification and award. CBT operations can reach the certification stage as the evaluation complies with 70% of the relevant minimum requirement and 60% of the advanced requirement indicators of each criterion. RP1 mentioned that regional recognition for the ASEAN tourism standards is based on an agreed number among all ASEAN Member States, which may promote equality but may hinder efficiency in promotion of tourism service quality. RP1 said, “in terms of how we recognize tourism standards regionally we select based on the numbers agreed by all ASEAN Member States.” As Wong et al. [

20] mentioned, the political culture within ASEAN is based on consensus and the principle of equality, which has an influence on the improving of a tourism collaboration at the regional level and identifying strengths and weakness of CBT communities by applying ASEAN CBT Standard. Therefore, ASEAN Tourism Standards Award is given to recipient countries based on their principle of equality, meaning the same number of awardees per country despite their varying levels of tourism development and performance.

4.2. Independent Review Mechanism

Currently, the ASEAN Tourism Standard Award does not have an independent review mechanism for the submissions by respective ASEAN member states. In order to improve the suitability of the ASEAN Tourism Standards Award, an independent review mechanism for the submissions by each ASEAN Member State is recommended as revealed in the interview. The evaluation process, including audit, review, and assessment, should depend on the result of the independent review in order to increase the transparency and efficacy of the award itself. RP1 commented “independent body at the regional level should review the candidates as level of implementation of review or assessment could be different from one to another”.

The lack of independent review mechanism implies (1) exposure to subjective interpretation of the evaluation criteria, (2) lack of willingness of each ASEAN Member State to take the third party’s opinion in order to increase real quality, and (3) decisions susceptible to political influence. Challenges in introducing an independent review mechanism may include (1) limited financial support, (2) increased cost of capacity building, and (3) heavy dependency on donor organizations especially in the case of poor communities [

10]. Given the significance of an independent review process and the benefits it can bring, CBT operators may need to consider what the independent evaluation process will entail. Likewise, ASEAN member states also need to envision long-term sustainability of standards through an external evaluation system. They would consider improving the evaluation system by involving a cross-country assessment among countries increasing the fairness within ASEAN, as RP1 mentioned.

4.3. Localization of ASEAN CBT Standard

After the adoption of the ASEAN CBT Standard in 2016, RP2 mentioned that the ASEAN CBT Standard was translated into local language and disseminated at the provincial and district levels. There were also training programs targeting locals, such as the Training of Trainers (ToT), at the provincial level with the aid of NGOs and international development partners. Master trainers could share their experience with the local trainers on how to implement the ASEAN CBT Standard in the community and the villages in order to increase the level of awareness. However, there have also been challenges as some criteria of the ASEAN CBT Standard were not agreeable with the local conditions. RP2 mentioned “there are too many criteria in the ASEAN CBT Standard that are too high for the Lao CBT model. That’s why we are developing our own standard. It is lower than the ASEAN CBT Standard so community can first meet the Laos CBT Standard before applying to the ASEAN CBT Standard. But two of them share the same goal.”

The MICT of Laos worked on the draft of the Lao CBT Standard in its language based on the framework of ASEAN CBT standard in 2021 and announced the Standard in 2023.

Before the ASEAN CBT Standard came to Lao PDR in 2016, there was not any CBT standard or certification scheme in Laos. However, there still existed best practices and cases such as the UNESCO-National Tourism Authority NHEP, the first community-based ecotourism project in Laos. In the past, the NHEP has been widely recognized as a model example of CBT throughout Southeast Asia. Although, the ASEAN CBT Standard can be a useful tool to improve CBT activities in the region and to create a robust system, but the criteria is rather high for Laos, as voiced by both RP2 and RP3. RP3 shared its thoughts by saying, “I think the assessment criteria of ASEAN CBT Standard is appropriate and suitable. But each country has different issues to follow all the criteria and it is not easy to meet all the criteria written in the ASEAN CBT Standard”.

Not surprisingly, application of ASEAN CBT Standard across the country is still sluggish due to the imbalance of knowledge and information asymmetry among stakeholders. With the technical assistance from developmental partners, the Laos National Tourism Organization is providing training opportunities through workshops and forums to strengthen the capacity of government officials and the community while sustainably managing CBT growth.

4.4. Partnership between the Private Sector and the Community

RP2 stressed that CBT should always involve the private sector and the local community. The private sector can sell community-based tourism products as part of their tour package through the promotion and joint marketing with tour companies. Therefore, PPP and community involvement is important for CBT success as the private sector can connect visitors to the local community. Unless there is direct income generated through the CBT activities, it would not be easy to encourage local communities to actively involve themselves in CBT activities. Therefore, efforts should be coordinated to expand job opportunities for all community members.

RP3 mentioned that in 2000, the Nalan Trail started out with two main trails, designed for a two- or three-day trekking program. In compliance with provincial law of Luang Namtha, the local people and the government were responsible for the implementation and management. Between 2009-2010, the government opened the trails to all private agencies so that new 12 trails can be connected to the Nalan Trail and achieve synergy. As a result, there are new 14 trails for trekking in Nam Ha National Protected Area. On the other hand, there are 48 families who have participated in the CBT program in Nalan Village, among which only 18 families maintain proper conditions to offer homestay. The rest of the families provide related services such as traditional performance, baci ceremony, handicraft souvenir, food and tour guide. Families render different services because respective households have different capacities and conditions. Ban Nalan was the first village to host tourists overnight by participating in the NHEP. RP3 stated “after receiving the translation of ASEAN CBT Standard, we (Luang Namtha Provincial Tourism Department) know where to go and are able to encourage community to enhance their offerings to meet the standard”.

Objective of the partnership between the private sector and the communities should align with to empowerment of the communities so that they can become equal players in the industry. However, there are many cases in Laos as well as in other ASEAN member states that the community is not fully equipped with the skills, knowledge, and resources to access tourism demand in a sustainable and inclusive way. As RP3 shared, willingness of the private sector in approaching the community as an equal partner is important. This approach drives the CBT projects forward, especially in developing countries such as Laos. As RP3 has shared through the case of Nalan village, community-oriented mechanism in close partnership with the private sector is the key in project management.

Therefore, it is important at the national level to support establishment of regulations and policies that enable partnerships between the community and the private sector to work together within the legal framework, rather than relying on partnerships that are market-based outcomes, as RP6 mentioned. To summarize, the main barriers that prevent partnership between the private sector and the community are 1) lack of endorsement from the government, 2) lack of confidence on the quality of products and proactive attitudes by the private sector to create new market opportunities, and 3) the lack of awareness by both the community and the private sector on the partnership potentials.

4.5. Lack of Demand for Recognition

RP4 mentioned that the standard is not a defining factor of what makes a successful CBT, though its usefulness is noted. The standard and certification still lacks widespread demand from the industry or the service providers in Laos. There are certainly some benefits of recognition for the CBT enterprises such as a certain degree of marketing effects, consumer confidence, and improved profile of the businesses, among others. RP4 mentioned “It is good for business. The ASEAN CBT Standard Award is always featured at the ASEAN Tourism Forum where not only high-level government officials but also many tourism operators around ASEAN are involved. I think that’s one of the biggest factors to drive the interests of tour operators as well as government. It is a good venue and give confidence to the businesses”.

On the service provider side, as RP4 puts it, villagers that have experienced CBT recognize the need for rules and framework to run the enterprise in a sustainable manner. On the consumer side, tourists who visit a Laos CBT destination certified through the CBT Standard can expect some credibility as it is endorsed by ASEAN. At the same time, visitors tend to have a certain level of anticipation on the minimum level of services that can be expected from the destination, thereby raising the consciousness of consumers on the usefulness of ASEAN tourism standards. Therefore, such credibility should be agreed upon by the three parties: the government, the operators, and the consumers. From the perspective of the community, there is a lack of demand to pursue ASEAN CBT Standard due to their inability to meet it in the short-run and directly market it.

Despite the strong regional ownership of the ASEAN CBT Standard, it is without limitations. RP4 commented that “ASEAN CBT Standard is good with strong regional ownership and political commitment, knowledge exchange among ASEAN member states. When it is implemented, it should be localized depending on country/local context. Even beyond the local context, for example, one type of CBT enterprise may not be necessarily relevant to another type of enterprise”.

A non-certified CBT enterprise may as well perform be better than a certified counterpart, especially when it has strong leadership, good community ethics, and good business practices, based upon RP4’s experience. In addition, RP5 argued that the private sector like hotels, guest houses, and tour operators in Laos seem to be indifferent towards the ASEAN CBT Standard as there are many other recognition options to choose from, including Travelife, EarthCheck, Sustainable Travel International, and Global Sustainable Tourism Council. At the same time, the tourism industry tends to place more creditability when standards are evaluated by an independent auditor rather than by a government-operated system. RP5 said “in my experiences working with standards, the third party and independent system for standards are considered more neutral and have more integrity than a purely government run system”. To this end, the private sector in Laos may not see substantial marketing benefits through ASEAN CBT certification. Also, they tend to believe that the certification may not have a significant impact in boosting the number of visitors. The reasons for lack of demand can be summarized as: 1) perceived lack of marketing benefits from the private sector, 2) lack of perceived credibility by consumers due to imbalanced previous experiences, and 3) the availability of options for other recognition schemes.

4.6. Multilateral Stakeholder Collaboration Efforts

In general, for development of CBT enterprises there is a high level of collaboration among government, private sector, community, and tourists. Objectives of the CBT usually align with government policy to create jobs and reduce poverty, while tour operators are aware of the CBT values, which in turn allow them to provide extra offerings for the visitors. Communities gain substantial income source to sustain their families, and tourists look for authentic experiences with the people from the community.

Although RP6 asserted that it was not difficult to involve local communities by hiring villagers for food and beverage supply services and forest patrol in ranger programs, ultimately, the community cooperation should be formalized and some of the responsibilities transferred to the community, which will facilitate empowerment of the community members.

For multilateral stakeholder collaboration, it is important to build trust and reliability among all involved parties through transparency and communication. Governments should facilitate involvement of the private sector so that it can initiate new activities and grow especially in and around 24 National Protected Areas (NPAs), considering the unique characteristics of Laos CBT. Regulations for tourism require special attention and should be treated differently from those on hydropower and the mining sector in the region if the government wants to ensure meaningful tourism development in Laos. Related stakeholders should bear in mind that the ultimate beneficiaries should be the host community, while the community should also contribute to the product in a meaningful way in terms of authenticity and marketability. RP7 raised the need for systemic training and educational opportunities from international development agencies for local staffs who are directly dealing with tourists for better implementation of the CBT Standard. The interviewee shared that most of the community staffs lack knowledge on the standard itself as well as understanding of the need for evaluation or monitoring of tourism quality.

5. Discussion and Implications

The results show a diversity of perspectives on enabling factors and major challenges in implementing ASEAN CBT Standard into Laos at the national level through executive-level stakeholder interviews from various public and private organizations. Findings suggest that for a successful implementation, the community should work with the private sector from the early stage of the development of CBT, as demonstrated in NHEP in Laos [

20,

21]. Specifically, the local communities can take advantage of partnering with the private sector and by expanding income generation opportunities. In addition, the interviewees indicated that international development agencies’ involvement in the tourism sector and its financial support to the Lao government’s CBT development efforts should be continued. Capacity building for public officials in tourism sector to establish systems and procedures and to implement regional tourism standards would be an important part of the training. Therefore, multi-stakeholders’ approach in implementing of CBT standard would serve as effective tool to further utilize and stabilize the Standard. The interviewees also shared their view on the ASEAN CBT Standard, which could be too demanding to attain them on their own, for most communities. Most of them, if not all, need technical assistance to achieve the Standard. Also highlighted is how ASEAN CBT Standard can be further promoted, accepted, and utilized by key stakeholders of CBT in Laos. As suggested and implied by the executive stakeholders of CBT in Laos during the interview, the MICT of Laos, NTO adopted not only the ASEAN CBT Standard in 2016 but also the Laos CBT Standard in 2023. This adoption of Laos CBT Standard validated the necessity of national standard which transformed from the ASEAN CBT Standard in consideration of the state of tourism development of the respective member states. This implies that ASEAN CBT Standard is a useful, necessary, and strategic framework as each ASEAN member state can follow to be competitive destinations under the umbrella CBT standard. The executive interviewees echoed the adoption of ASEAN CBT standard itself is a big step for community-based tourism development in Laos. However, despite these accomplishments, it was suggested during the interview that national CBT standard can be the first step for local communities so that CBT standard practices in Laos would accelerate the implementation of the ASEAN CBT standard, a transnational, collective and regional standard.

6. Conclusions

This research findings highlight the need for consideration of national tourism development status in applying ASEAN CBT Standard in respective ASEAN member states. Although the ASEAN CBT Standard is a collective effort of adopting a common framework in the ten member states, the NTO of the respective countries, like the one in Laos, can assist local communities to meet the national level CBT standard first, if applicable, with the help of private sector and international development partners. The result of executive-level stakeholder interviews show that multi-stakeholder approach and improvement of evaluation system of the Standard implementation of community is necessary for further development of the CBT in Laos. From this perspective, it is recommended that public-private partnership for better implementation of the localized CBT Standard in Laos. In addition, it is also suggested to monitor and assess the progress of the Lao CBT Standard, which was adopted in 2023. If the local communities in Laos can accept and apply the localized CBT Standard, it will be the first step toward successful implementation of regional CBT Standard to increase collective competitiveness as an umbrella tourism destination brand.

This study is limited in that it focuses on a single ASEAN member state, Laos, even though Laos constitutes a unique case for investigation. Future research can attempt to examine the implementation status of other ASEAN member states, especially focusing on Greater Mekong Subregion(GMS). GMS countries, namely Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam have been marketing collectively as a tourism destination. Additional research on these ASEAN member states with respect to differences in resources and circumstances in implementation of CBT Standards can be useful. In this regard, the interviews with Lao local community can be utilized learn about the various perspectives with regard to the progress of Laos CBT Standard since its adoption in 2023, including the benefits and challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S. K and S.K.L.; methodology, S.K.; formal analysis, S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y. , J.K. and S.K.L; supervision, Y.Y. , J.K. and S.K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- Asia Development Bank. The Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism Enterprises in the Lao PDR: An Initial Assessment. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/BRF200187-2 (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- United Nations Development Programme. Lao PDR’s tourism COVID-19 recovery roadmap 2021-2025. Available online: Lao PDR Tourism COVID-19 Recovery Roadmap for 2021-2025 | United Nations Development Programme (undp.org) (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism. Statistical Report on Tourism in Laos 2019. https://www.laos-dmn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Statistical-Report-on-Tourism-2019.pdf (accessed on 25 Juen 2024).

- Harrison, D.; Schipani, S. Lao tourism and poverty alleviation: Community-based tourism and the private sector. Curr. Issues Tourism. 2007, 10, 194-230. [CrossRef]

- Marić, I. (2013). Stakeholder analisys of higher education institutions. Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems: INDECS, 11(2), 217-226.

- Lyttleton, C.; Allcock, A. Tourism as a Tool for Development: UNESCO-Lao National Tourism Authority Nam Ha Ecotourism Project. 2002.

- Schipani, S.; Marris, G. Linking conservation and ecotourism development Lessons from the UNESCO-national tourism authority of Lao PDR Nam Ha Ecotourism Project. Bangkok, Thailand: UNESCO. Available online: http://lad.nafri.org.la/fulltext/3973-0.pdf (accessed on 24 Juen 2024).

- Asia Development Bank. Proposed Grant to the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Loan to the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam: Greater Mekong Subregion Sustainable Tourism Development Project. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-documents//38015-reg-rrp.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Suansri, P.; Yeejaw-haw, S. Community BASED TOURISM(CBT) STANDARD HANDBOOK, Suansri, P., Richards, P., Eds.; Wanida Karnpim Limited Partnership: Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2013; pp. 22-25.

- Novelli, M.; Klatte, N.; Dolezal, C. The ASEAN Community-based Tourism Standards: Looking Beyond Certification. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2017, 14(2), 260-281. [CrossRef]

- The ASEAN Secretariat. Available online: https://www.asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/ASEAN-Community-Based-Tourism-Standard.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Pio, A. An Analysis of Community-Based Tourism Partnership in Lao PDR. Master’s Thesis. NHTV University of Applied Sciences, The Netherlands, September 2011.

- Ashley, C.; Jones, B. Joint Venture Between Communities and Tourism Investors: Experience in Southern Africa. Int. J. Tour. 2001, 3, 407-423 . [CrossRef]

- Seidman, I. Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences; New York, NY: Teachers College Press, 2013, pp.39-48.

- Weber, R.P. Measurement Models of Content Analysis. Qual. Quant. 1983, 17, 127-149. [CrossRef]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Kirilenko, A.P.; Morrison, A.M. Facilitating Content Analysis in Tourism Research. J. Travel Res. 47, 454-469. [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.H.; Densten, I.L. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis using Latent and Manifest Variables. Qual. Quant. 1998, 32, 419-431. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M. Community benefit tourism initiatives – A conceptual Oxymoron? Tour. Mang. 2008, 29, 1-18.

- ASEAN Secretariat. Available online: Joint Media Statement of the Twentieth Meeting of ASEAN Tourism Ministers - ASEAN Main Portal (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Wong, E.P.; Mistilis, N.; Dwyer, L. A framework for analyzing intergovernmental collaboration: The case of ASEAN tourism. Tour. Mang. 2011, 32, 367-376. [CrossRef]

- Ounmany, K. Community-Based Tourism in Laos: Benefits and Burdens Sharing among Stakeholders. PhD Dissertation, BOKU University, Vienna, October 2014.

- Phommavong, S. International Tourism Development and Poverty Reduction in Lao PDR. PhD Dissertation, Umea University, Sweden, November 2011.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).