1. Introduction

According to the European Organization for Health and Safety at Work, psychosocial risks and occupational stress are among the greatest challenges in the fields of occupational safety and health. They significantly affect the health of individuals, businesses, and national economies. Psychosocial stressors threaten employees and managers within organizations in the public and private sectors [

1,

2]. In the last 12 years of the economic crisis in Greece, an "exponential" escalation of these psychosocial hazards was experienced, which—to a greater extent—has worsened during the COVID-19 era and post-COVID-19 era at both the national and international levels [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Psychosocial risks arise from inadequate planning, organization and management of work, as well as from an unhealthy social context of the work environment, and may lead to negative physical, psychological, and social outcomes for employees, such as work stress, burnout and/or depression [

7,

8,

9]. Some examples of working conditions that may lead to psychosocial risks include excessive workload, conflicting demands and ambiguities regarding employees’ roles, a lack of participation in decision-making, a lack of influence on how the work is carried out, poor management of organizational change, job insecurity, ineffective communication, a lack of support from management or colleagues, psychological and sexual harassment, violence, etc. [

10,

11,

12].

A psychosocially healthy work environment increases performance and personal development and reinforces the physical and mental well-being of employees [

13,

14]. Employees experience stress attacks when the demands of their work are excessive and exceed their ability to cope with them. In addition to mental health problems, workers suffer from prolonged stress with a high risk of developing serious physical health problems, such as cardiovascular disease or musculoskeletal problems [

15,

16]. At the organizational level, negative consequences may include poor overall business performance, increased absenteeism, truancy (instances of employees showing up to work while ill and unable to function effectively) and increased accident rates and injuries. Stress-related absences tend to be longer than absences related to other causes, and work-related stress contributes to increased early retirement rates. The costs to businesses and society are estimated to be significant and amount to billions of euros [

17,

18].

Furthermore, leadership is another crucial psychosocial aspect that plays a significant role in managerial interventions and policies. The impact of leadership behaviour and style on employees' health and well-being has been identified as a noteworthy psychosocial risk factor [

19,

20]. Effective leadership includes actively engaging health professionals by attentively listening to their problems and expectations, facilitating collaborative team planning, and appropriately allocating workloads. By carefully considering employees' psychological needs and implementing supportive leadership practices, managers and policymakers can cultivate a work climate that fosters well-being and productivity [

21,

22,

23]. Workplace bullying is an additional psychosocial aspect that impacts management responses and legislation. Research has indicated that several psychosocial characteristics within the workplace, including but not limited to quantitative demands, job control, role expectations, leadership conduct, and the social climate, are associated with workplace bullying. The primary emphasis of interventions to prevent workplace bullying should be enhancing psychosocial working conditions, decision-making processes, leadership abilities, and other organizational aspects [

24,

25,

26]. By considering these various elements, managers and policymakers can establish a work atmosphere that fosters respect and inclusivity, enhances employee well-being and mitigates the likelihood of bullying [

27,

28,

29].

In Greece, employers have a legislative obligation to assess psychosocial risks, such as the risks of violence and harassment, including sexual harassment, and are expected to take measures to prevent and control such hazards in the workplace (amendment of paragraph 6 of article 42 of Law 3850/2010). Employers are required to take specific measures to prevent and address violence and harassment at work; demonstrate zero tolerance for such incidents or behaviour when receiving and being called upon to manage related complaints; and provide information and training on the risks, prevention, protection and obligations of those involved in accessible formats (Law 4808/2021).

The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) was originally developed in 2000 for research purposes at workplaces in Denmark, and it has since been validated in 18 countries [

30]. It covers all important psychosocial factors at work, considering the leading concepts and theories of occupational health and well-being [

31,

32]. The COPSOQ International Network (

http://www.copsoq-network.org) was founded in 2009 to promote scientific research and risk assessment via the COPSOQ tool. COPSOQ may be used by governments, universities and research institutions, enterprises and social agents from Europe and other countries worldwide [

33]. The network emphasizes the importance of validation studies supporting tailored national versions of the instrument.

The COPSOQ is a comprehensive questionnaire that covers a wide variety of dimensions, describes psychosocial working conditions, and is considered an instrument for research and psychosocial risk prevention in the workplace [

33]. Researchers [

31] have reported that the COPSOQ can be used as a valid and reliable tool for psychosocial risk assessment in the workplace, which is why it has been used in thousands of enterprise-based risk assessment applications [

34]. It can capture a broad range of psychosocial dimensions [

35] and is part of a systematic occupational safety and health management system [

36].

The questionnaire covers a broad range of aspects of currently leading concepts and theories, such as the job characteristics model, the Michigan organizational stress model, the demand-control (support) model, the sociotechnical approach, the action-theoretical approach, the effort-reward-imbalance model, and the vitamin model [

35]. COPSOQ I and II have short, middle, and long versions [

36]. A new version of the questionnaire (COPSOQ III) was developed by the International COPSOQ Network as an update of the previous two versions [

35,

36]. A set of core items of the COPSOQ III is strongly recommended to be included in the national short, middle, and long versions of the questionnaire [

30]. Many items and scales of COPSOQ III have been included in the COPSOQ questionnaire since 2005. In total, 58 of the 84 items (approximately 70%) are identical [

37].

The new version of COPSOQ III is designed to allow flexible adaptation to national and industry-specific contexts without compromising the potential for international comparisons and comparisons over time. National versions can be established by the national COPSOQ teams of each country on the basis of all “core” items supplemented with additional items labelled “middle” or “long” to form a reliable and relevant tool in the given context. Therefore, all future national versions include the same mandatory core items, while the total number of items in scales and the number of scales are allowed relative flexibility [

30,

38].

COPSOQ III has been validated for the German, Spanish, French, Swedish, and Dutch languages [

39,

40] as well as in many countries worldwide (e.g., Canada and Chile). There is also an important validation study (available also on the COPSOQ-Network website) with the content of a joint-effort validation for the international middle version of COPSOQ III. An international validation study could be used as a linguistic “common point of reference” for both scientific research and practical implication-related projects [

30].

The Greek validation study project was initiated in Greece in October 2017 at the University of Piraeus, Greece. A small part of its research findings and relevant conclusions have been presented at Employability for the 21st Century International Conference, which took place in Leuven-Belgium in September 2018 [

41]. More relevant findings have been included in Dr. Kotsakis’ doctoral thesis [

42]. An up-to-date part of the current study’s findings were also presented in the Psychosocial Health Workshop for Greece and Cyprus, which took place in Nicosia-Cyprus in February 2023, under the auspices of the Open University of Cyprus.

The aim of the current study was to assess the reliability and validity of the psychometric properties of the Greek long version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire III (COPSOQ-III-GR) in a comprehensive manner.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in Greece in the context of both doctoral and postdoctoral research activities at two Greek universities (University of Piraeus-Greece and University of Patras-Greece) between 2017 and 2022. Owing to data quantity- and data quality -related restrictions and our overall filtering process results, we ultimately included only the data from the University of Piraeus research activities. The participants were employees from different public and private organizations.

Ethics Statement

The survey was implemented in accordance with the COPSOQ International Network Research Guidelines and in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of Greece. The research study, which complied with the COPSOQ Network Research Guidelines with respect to anonymity, confidentiality and research ethics and the overall research study protocol, was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Piraeus. The respondents were given personalized credentials to access the questionnaire through a provided URL to the Aca-demic Research Radar. A written user manual was given to the respondents with instructions on how to access the survey and a notice that by clicking on the link to proceed to the survey, they were providing consent to participate. Participation was performed anonymously, and the system was not able to identify an individual by his/her name or any other direct identifier. The system initiating the survey was used as a record of consent.

Sample

The aim of the study was to test the psychometric equivalence and validate the Greek translation of the long version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ III-GR) in a sample of Greek employees (N>2000). The study sample comprised 2,189 participants who completed all the survey questions [

43]. For the development and conduct of the COPSOQ III-GR study, the authors received approval from the International COPSOQ Network.

The Greek Version of COPSOQ III

The overall design and content of the new Greek version (III) of the questionnaire was based on a scientific collaboration outcome between the Hellenic COPSOQ Research Team (University of Piraeus, Greece) and the Steering Committee of the International COPSOQ-Research Network (since 2017, October). The overall development process of the Greek COPSOQ ΙΙΙ was carried out in three (3) phases. In the first phase, the Greek version III instrument was constructed (based on the German COPSOQ-III scales and including a few add-on scales from the COPSOQ-II scales). In the second phase, forward-backwards translation and cultural adaptation of the COPSOQ-III (GR) questionnaire were performed. In the third phase, the psychometric properties of the new COPSOQ-III (GR) version were evaluated in several cross-sectoral and cross-occupational samples of Greek employees (N=2189). The permission to design and validate the Greek III version of the diagnostic tool was obtained by the Steering Committee of the International COPSOQ network in the context of academic research activities of the School of Economics, Business and International Studies at the University of Piraeus, Greece. Many COPSOQ-related activities are still ongoing at both the University of Piraeus and the University of Patras.

The core version of the Greek COPSOQ-III (core) included a total of 108 items and twenty-one (21) core scales. Answers to all the questions were given through Likert-type scales. It has been designed under a job demands-control and domain-centric approach and is based on the COPSOQ German-III version. The first pilot study (N=426) used the first core scales (21 scales). The findings of the pilot study were presented in the Employability for the 21st Century International Conference Proceedings in Belgium [

41]. Within 2019, the Greek version was re-engineered and finalized to support international comparisons and benchmarking. Today, it is available in two (2) official releases for Greece and Cyprus (Language: GR), the COPSOQ III-GR Long Version (108 items, 40 scales) and the COPSOQ-III-GR Middle Version (74 items, 24 scales) (see Domains & Items per scale table in extended data) (Appendix A).

The new “long” version of the COPSOQ III (GR) questionnaire was shared in two different ways (internet-cloud and in writing). With respect to the companion letter-paper documentation for the COPSOQ-III (GR) questionnaire, the participant-consent form, the relevant cover letter explaining the purpose of the research study, and the researchers’ affiliation were enclosed in the same envelope. The full paper set was handed over to employees who belonged to many different occupational sectors. In the case of a company or an organizational entity having concerns about the participation of their employees in the study, written approval from the scientific committee or the HR department of the company was an additional prerequisite of our study. Regarding the “internet-cloud version” of the questionnaire, two types of internet-cloud-based applications were selected during the overall survey-feedback collection process. The first application was a secure cloud-interface application based on Google Forms. The second application was a Microsoft Azure application, named Academic Research Radar (A.R.R.), which is a cloud platform that supports specific parameterizing, building, distributing and administering online surveys under top-security and confidentiality specifications (powered MS-Azure-specific services and overall data management). As an original Azure app, the ARR cloud platform took full advantage of the “Microsoft Azure Compliance Manager” solution. The Azure Compliance Manager is a free, Microsoft cloud services solution designed to help organizations meet complex compliance obligations, including the GDPR, ISO 27001, ISO 27018, and NIST 800-53, with the aim of helping both the academic research community assess, implement and manage Azure security policies and GDPR compliance-related policies from within Microsoft Azure Cloud applications. The ARR platform is used by academic staff and researchers to collect any type of “voice of the employee” feedback via a secure online cloud interface powered by Azure GDPR compliance features. In our study, the ARR Azure application was parameterized to support the COPSOQ-III (GR) academic surveys in terms of confidentiality, security, participants’ anonymity, organizational-entity anonymity and GDPR compliance at the national level. Thus, both types of electronic participation—Google forms and the Microsoft Azure App—were two (2) fully anonymous and confidential user interfaces (for the participants) in terms of electronic form fill-in, data storage, confidentiality, compliance and overall survey data processing.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed via Statistical Software R (version 4.2.0). Cronbach’s α and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were computed to assess the reliability and homogeneity of the scales in the sample. We used the Cronbach-Alpha function from the ltm package (version 1.2) [

44] to calculate the Cronbach’s α and the icc function from the irr package (version 0.84.1) [

45]. To explore the characteristics of each scale’s distribution, we calculated the mean, standard deviation, and floor and ceiling effects via base R functions (e.g., mean, sd). The floor effect is defined as the percentage of answers coded zero, whereas the ceiling effect is defined as the percentage of answers coded 100. We also assessed the internal validity and distinctiveness of the scales via Pearson’s correlations and multivariable relationships via explorative factor analysis (EFA) and generalized linear regression models. For Pearson correlations and generalized linear regression, we used the cor and glm functions respectively, from the basic R stats package. For the EFA, we used the EFA function from the EFAtools package (version 0.4.4) [

46] via the rotation method (varimax with Kaiser normalization; eigenvalue of at least 1 as the criterion). Statistical significance was considered at the level of < 0.05.

3. Results

The sociodemographic and occupational characteristics of the sample are presented in

Table 1. From a sociodemographic perspective, 49.5% of the participants in the sample were female, and 50.5% were male. In terms of age, 31.7% of the participants were up to 24 years of age, 17.2% were between the ages of 25 and 34 years, 30.7%, 17.2% and 3.2% were between the ages of 35 and 44 years, 45 to 54 years, and 55 years or older, respectively. A total of 43.6% of the participants were working in the public sector, whereas 56.4% were working in the private sector. The largest percentage of employees (25.9%) were working in “admin, not leading” occupations, and the smallest percentage (2.6%) were working in “tech: engineers” occupations. In terms of interaction with external clients, 42.2% of the participants stated that they did not have any interaction, 4.7% had on average, less than 1 interaction per day, 6.9% had 1 to 5 interactions per day, 10.6% had 6 to 14 interactions per day, and 35.6% had 15 or more interactions per day. Finally, 21.5% of the participants were supervisors, whereas 61% were not supervisors in jobs with supervisors and 17.5% were not supervisors in jobs with no supervisors (e.g., freelancers).

The 40 scales of the Greek COPSOQ III questionnaire are presented in

Table 2. The means, standard deviations, and fractions with ceiling and floor effects were calculated for each scale to assess sensitivity and variation. The mean values of the scales varied from 0.3 for “Physical Violence” to 71.55 for “Work Pace”. The standard deviations of all scales ranged from a minimum of 3.1 points to a maximum of 38.96 points. Floor effects ranged between 48% and 99.18%. There were 4 scales with scores of 90% or more in this category (“Cyber Bullying”, “Physical Violence”, “Sexual Harassment”, “Threats of violence”), whereas 3 scales had scores of less than 10% (“Influence”, “Variation of Work”, “Work Pace”). The ceiling effects ranged between 0% and 55.29%. In addition, there were 4 scales exceeding 20% (“Bullying from Customers (External)”, “Demands for Hiding Emotions”, “Influence”, “Mobbing”), whereas 22 scales provided fewer than 5% answers in this extreme category.

Table 2 also shows the Cronbach’s Alpha and the intraclass correlation (ICC) for each scale. There is a broad consensus that a value of α ≥ 0.7 is an indicator of acceptable reliability, and a value of ICC ≥ 0.5 is an indicator of an acceptable degree of congruence. In total, 22 scales showed good reliability in relation to Cronbach’s Alpha, and 16 scales showed good homogeneity in terms of the ICC.

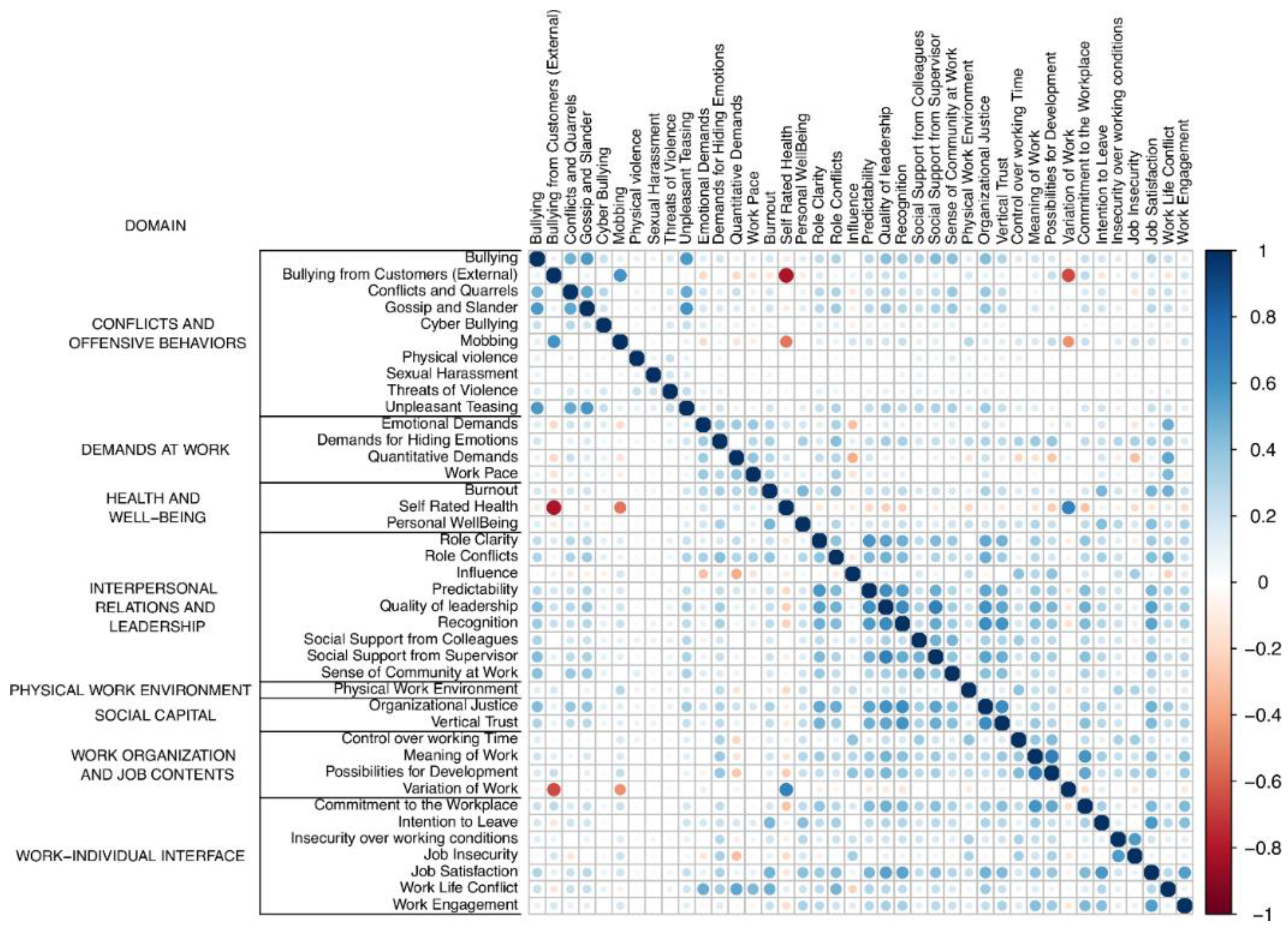

In

Figure 1, we present the pairwise correlation coefficients (Pearson’s r) as indicators of the internal validity and distinctiveness of the scales. Usually, if “r” is lower than |0.1|, the correlation is said to be negligible. Values between |0.1| and |0.3| are considered weak correlations, values between |0.3| and |0.5| are considered moderate correlations, and values greater than |0.5| are interpreted as strong correlations. In this sense, out of a total of 780 pairwise correlations, “r” was weak in 613 cases (78.6%), moderate in 133 cases (17.1%), and strong in 34 cases (4.4%), with -0.81 being the strongest correlation (between “Self-Rated Health” and “Bullying from Customers (External)”).

Exploratory factor analysis was used to assess the statistical relationships for a multitude of scales. In

Table 3 and

Table 4, we delineate the results of the EFA performed by treating work factors and effects separately in accordance with the generalized model of cause and effect. In both tables, all factor loadings lower than |0.4| are hidden for better readability. In

Table 3, components were extracted from the 34 psychosocial work factors, with the sum of the squared loadings explaining 44.8% of the total variance.

Table 4 shows that out of the 6 scales of effects, 2 components were extracted, covering 48.0% of the total variance.

Finally, we applied six multiple linear regression models. The satisfaction and health scales are each defined as outcome (dependent) variables to be predicted by the 34 work factors. All regression estimates and standard errors are presented in

Table 5, with the star symbols indicating the statistical significance of each variable.

Table 6 shows the variance explained (determination coefficient R2) by a model including all 34 workplace factors as independent variables (i.e., full model) and by a model including only the top five factors selected as those having the lowest p values (i.e., most statistically significant variables) in the full model.

Table 6 also shows the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the degrees of freedom (df) for each model.

Burnout was much better than all other effects were predicted (R2 = 0.905), which means that 90.5% of its variance was explained by the model. The top five predictors for “Burnout” were “Work Life Conflict”, “Work Pace”, “Job Insecurity”, “Quantitative Demands” and “Role Conflicts”. Consequently, “Job Satisfaction” (R2 = 0.876), was followed by “Work Engagement” (R2 = 0.806), “Self-Rated Health” (R2 = 0.795), “Personal Well-being” (R2 = 0.718), and “Intention to leave” (R2 = 0.564). The top five predictors for “Job Satisfaction” were “Recognition”, “Quality of leadership”, “Commitment to the Workplace”, “Role Conflicts” and “Physical Work Environment”. The top five predictors for “Work Engagement” were “Commitment to the Workplace”, “Meaning of Work”, “Influence”, “Bullying”, and “Vertical Trust”. The top five predictors for “Self-Rated Health” were “Variation of Work”, “Bullying from Customers (External)”, “Work Pace”, “Influence” and “Social Support from Colleagues”. The top five predictors for “Personal Well-being” were “Bullying from Customers (External)”, “Insecurity over working conditions”, “Commitment to the Workplace”, “Role Conflicts”, and “Role Clarity”. Finally, the top five predictors for “Intention to Leave” were “Bullying from Customers (External)”, “Commitment to the Workplace”, “Meaning of Work”, “Role Conflicts” and “Job Insecurity”.

4. Discussion

In summary, our validation study of the Greek COPSOQ III version showed adequate reliability and validity, which is in line with the validation of the COPSOQ III questionnaire from other European countries. For example, our findings are compatible with the validation of the German COPSOQ III [

37], which found either good or very good reliability and validity for most of their 84 items and 31 scales. On the basis of the statistical analyses and findings of the current study, there is substantial evidence that the top work-environment predictor for burnout syndrome-related risk in Greece is an imbalance between work-life and family-life. The top predictor for “Self-rated Health”, “Personal Wellbeing” and “Intention to Leave” related risk is “External Bullying” (Bullying from Customers). Thus, “Bullying from Customers” is a common predictor for all three of the above three (3) psychosocial effects on Greek employees. In addition, the top predictor for “Work-Engagement” (lack of work-engagement) is the work-environment factor “Commitment to the Workplace” (lack of commitment to the workplace). Finally, the top predictor for the lack of “Job Satisfaction” risk is the lack of “Recognition”. In more detail, our regression analysis also revealed that 34 psychosocial work factors can predict, with good accuracy, the scores of the satisfactory and health scales. First “Burnout” was predicted much better than all other effects, next was “Job Satisfaction, followed by “Work Engagement”, “Self-Rated Health”, “Personal Wellbeing”, and “Intention to Leave. The analysis also revealed the top five predictors for each outcome variable. The top five predictors for “Self-Rated Health” are “Variation of Work”, “Bullying from Customers (External)”, “Work Pace”, “Influence” and “Social Support from Colleagues”.

The top five predictors for “Intention to Leave” are “Bullying from Customers (Exter-nal)”, “Commitment to the Workplace”, “Meaning of Work”, “Role Conflicts” and “Job Insecurity”. As nurses account for the largest number of workers in most healthcare systems, these factors play an important role [

47]. Different studies agree with our results that occupational factors such as poor managerial support, lack of meaning for work, role conflicts, lack of opportunities for job promotion, job stress, and work–reward imbalance can be associated with employees’ intention to leave [

48,

49]. Another study has shown that a supportive work climate is a predictor of retaining the nursing profession [

50].

The top five predictors for “Job Satisfaction” were “Recognition”, “Quality of leadership”, “Commitment to the Workplace”, “Role Conflicts” and “Physical Work Environment”. Literature review has shown that nurses job satisfaction predictors include working conditions, relationships with coworkers and leaders, pay, promotion, security of employment, responsibility, and working hours [

51,

52]. The top five predictors for “Personal Well-being” were “Bullying from Customers (External)”, “Insecurity over working conditions”, “Commitment to the Workplace”, “Role Conflicts”, and “Role Clarity”.

The top five predictors for “Burnout” were “Work Life Conflict”, “Work Pace”, “Job Insecurity”, “Quantitative Demands” and “Role Conflicts”. For example, research consistently found that adverse job characteristics such as high workload, low staffing levels, long shifts, low control, low schedule flexibility, time pressure, high job and psychological demands, low task variety, role conflict, low autonomy, negative nurse‒physician relationships, poor supervisor/leader support, poor leadership, negative team relationships, and job insecurity, are associated with burnout in nursing [

53].

The top five predictors for “Work Engagement” were “Commitment to the Workplace”, “Meaning of Work”, “Influence”, “Bullying”, and “Vertical Trust”. Work engagement is a positive, fulfilling state of mind about work that is characterized by vigour, dedication and absorption. Trust (organizational, managerial, and collegiality) and autonomy are the antecedents of work engagement [

54]. In nursing, work engagement is a dedicated, absorbing, vigorous nursing practice that emerges from settings of autonomy and trust and results in safer, cost-effective patient outcomes. From this definition, work engagement can be developed as an explanatory middle range theory that conceptually captures the concerns that health professionals have about their work environment. The assumptions that underlie work engagement, the linkages between the antecedents of autonomy and trust and the relationships between the antecedents of trust and autonomy and the closely related concepts of transformational and authentic leadership styles are some of the remaining areas to be developed in the middle range theory.

Our study is the first to be conducted in Greece to validate the COPSOQ III Greek version of this internationally applied tool; nevertheless, several limitations of our study should be acknowledged. We believe that the study sample (N=2.189) was adequate, and that the internal consistency of the subscales was satisfactory. Although our study included employees from a variety of occupational sectors and different types of workplaces in Greece, we were not able to perform sector analyses to assess possible differences in the performance of the tool. We recognize our conveniently chosen sample, which precludes the generalization of our findings. In addition, during the study, we did not perform “test‒retest” reliability because we distributed the GR-Long version of the COPSOQ-III questionnaire (108 items, 40 scales).

In summary, the COPSOQ III provides a comprehensive framework for assessing psychosocial factors at work, which is crucial for designing effective public health strategies. The Greek validation study of the COPSOQ III highlights its utility in identifying key psychosocial stressors, such as work‒life conflict, bullying, job insecurity, and role conflicts, which are significant predictors of mental health outcomes such as burnout and job satisfaction. By incorporating COPSOQ III into public health strategies, policymakers and health professionals can better understand and address the psychosocial dimensions of occupational health. For example, the results from the COPSOQ III study can inform targeted interventions aimed at reducing work-related stress and enhancing employee well-being. Public health initiatives can leverage these data to implement supportive policies, such as flexible work arrangements, antibullying programs, and leadership training, which are critical in mitigating the adverse effects of psychosocial stressors [

55]. Additionally, the COPSOQ III can serve as a tool for ongoing monitoring and evaluation, ensuring that interventions remain effective and responsive to emerging psychosocial risks. In the context of broader public health challenges, the COPSOQ III Greek validation study aligns with findings from other research on mental health and workplace adaptations post pandemic. Additionally, researchers [

56,

57] emphasize the importance of addressing mental health comprehensively. These studies highlight the need for robust psychosocial assessment tools such as the COPSOQ III to support mental health initiatives and policy interventions. Furthermore, integrating COPSOQ III into public health strategies can increase the effectiveness of clinical interventions for mental health disorders in the context of psychotic spectrum disorders and bipolar disorder [

58]. By identifying workplace-related psychosocial risks, public health strategies can be tailored to address specific stressors that exacerbate mental health issues, thus improving overall treatment outcomes [

59,

60,

61].

Future research could explore cognitive-based interventions aimed at improving workplace cognitive function and reducing stress. Examining the underlying neuropsychological mechanisms by which workplace stress affects cognitive performance and overall mental health could provide deeper insights. Moreover, investigating the role of family support in mitigating workplace stress and promoting mental health among employees with high job demands would further this line of research. Comprehensive intervention strategies to address workplace bullying and harassment could be designed and evaluated, considering the psychosocial factors identified by the COPSOQ III. Assessing the impact of recent legislative changes on the prevalence and management of workplace bullying and harassment in Greece could provide actionable insights.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the Greek version of the COPSOQ III (GR) exhibited good psychometric properties for most of the scales of the questionnaire and met international standards. We are confident that the COPSOQ III (GR) can be recommended as a valid and highly useful instrument for research as well as for risk assessment within different public and/or private enterprises. COSPQO III (GR) covers a multitude of theoretical approaches and provides comprehensive information on psychosocial working conditions supporting evidence-based organizational research and diagnosis and facilitating advanced psychosocial risk management of organizational change for both public and private sector entities.

Author Contributions

A.K., D.A and M.S. conceived of the idea for the study; A.K., D.A., M.M., C.H., M.G. and M.S. contributed to the development of the study methodology; A.K., D.A., worked for the statistical and formal analysis; A.K., D.A., M.M., C.H., E.S.S., M.G. and M.S. paid particular attention and provided insights for the interpretation of the study findings; A.K., D.A., M.M., C.H., M.G. and M.S. were responsible for data management; A.K., D.A., M.M. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; A.K., D.A., M.M., E.S.S., C.H., M.G. and M.S. contributed to subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript; A.K & M.S. were in charge of project management and administration; All authors have read and approved of the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Authors have read and approved of the final version for publication

Availability of data and material

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Zenodo Repository at

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10949615. Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence (CC-BY 4.0).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study for their contribution. Additionally, we would like to thank the Steering Committee of the COPSOQ Network, for the overall scientific support and collaboration in the process for forward-backward translation as well as in the overall development and statistical validation process of the Greek COPSOQ-III questionnaire (COPSOQ-III-GR Long and Middle versions).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Magnavita, N., Soave, P. M., Ricciardi, W., & Antonelli, M. (2020). Occupational stress and mental health among anaesthetists during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 8245. [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Espert, M. D. C., Prado-Gascó, V., & Soto-Rubio, A. (2020). Psychosocial risks, work engagement, and job satisfaction of nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 566896. [CrossRef]

- Koren, H., Milaković, M., Bubaš, M., Bekavac, P., Bekavac, B., Bucić, L., Čvrljak, J., Capak, M., & Jeličić, P. (2023). Psychosocial risks emerged from COVID-19 pandemic and workers’ mental health. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. [CrossRef]

- Che Huei, L., Ya-Wen, L., Chiu Ming, Y., Li Chen, H., Jong Yi, W., & Ming Hung, L. (2020). Occupational health and safety hazards faced by healthcare professionals in Taiwan: A systematic review of risk factors and control strategies. SAGE Open Medicine, 8, 2050312120918999. [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, T., Yang, L. Q., Jiang, Z., Newman, A., De Cuyper, N., & Sekiguchi, T. (2021). Work-related psychosocial risk factors and coping resources during the COVID-19 crisis. Applied Psychology: Psychologie Appliquée, 70(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, V., Gkintoni, E., Halkiopoulos, C., & Karademas, E. C. (2024). Quality of Life and Incidence of Clinical Signs and Symptoms among Caregivers of Persons with Mental Disorders: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 12(2), 269. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Rubio, A., Giménez-Espert, M. D. C., & Prado-Gascó, V. (2020). Effect of emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks on burnout, job satisfaction, and nurses’ health during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7998. [CrossRef]

- van der Molen, H. F., Nieuwenhuijsen, K., Frings-Dresen, M. H., & de Groene, G. (2020). Work-related psychosocial risk factors for stress-related mental disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 10(7), e034849. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Kourkoutas, E., Yotsidi, V., Stavrou, P. D., & Prinianaki, D. (2024). Clinical Efficacy of Psychotherapeutic Interven-tions for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Children, 11(5), 579. [CrossRef]

- Franklin, P., & Gkiouleka, A. (2021). A scoping review of psychosocial risks to health workers during the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2453. [CrossRef]

- Taibi, Y., Metzler, Y. A., Bellingrath, S., & Müller, A. (2021). A systematic overview on the risk effects of psychosocial work characteristics on musculoskeletal disorders, absenteeism, and workplace accidents. Applied Ergonomics. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Skokou, M., & Gourzis, P. (2024). Integrating Clinical Neuropsychology and Psychotic Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Analysis of Cognitive Dynamics, Interventions, and Underlying Mechanisms. Medicina, 60(4), 645. [CrossRef]

- Obrenovic, B., Jianguo, D., Khudaykulov, A., & Khan, M. A. S. (2020). Work-family conflict impact on psychological safety and psychological well-being: A job performance model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 475. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni E, Ortiz PS. Neuropsychology of Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Clinical Setting: A Systematic Evaluation. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Aug 31;11(17):2446. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dar, T., Radfar, A., Abohashem, S., Pitman, R., Tawakol, A., & Osborne, M. (2019). Psychosocial stress and cardiovascular disease. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine, 21(5), 23. [CrossRef]

- Teo, S. T., Bentley, T., & Nguyen, D. (2020). Psychosocial work environment, work engagement, and employee commitment: A moderated, mediation model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, 102415. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R. Z. A. R., Zalam, W. Z. M., Foster, B., Afrizal, T., Johansyah, M. D., Saputra, J., ... & Ali, S. N. M. (2021). Psychosocial work environment and teachers’ psychological well-being: The moderating role of job control and social support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7308. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q., Dollard, M. F., & Taris, T. W. (2022). Organizational context matters: Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to team and individual motivational functioning. Safety Science. [CrossRef]

- Östergård, K., Kuha, S., & Kanste, O. (2023). Health-care leaders' and professionals' experiences and perceptions of compassionate leadership: A mixed-methods systematic review. Leadership in Health Services. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Barlou, O., & Beligiannis, G. N. (2021). Associations between Traditional and Digital Leadership in Academic Environment: During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerging Science Journal, 5(4), pp.405–428. [CrossRef]

- Boitshwarelo, T., Koen, M. P., & Rakhudu, M. A. (2020). Strengths employed by resilient nurse managers in dealing with workplace stressors in public hospitals. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 13, 100252. [CrossRef]

- Quinane, E., Bardoel, E. A., & Pervan, S. (2021). CEOs, leaders and managing mental health: A tension-centered approach. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(15), 3157-3189. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Barlou, O., & Beligiannis, G. N. (2019). Transition from Educational Leadership to e-Leadership: A Data Analysis Report from TEI of Western Greece. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 18(9), 238–255. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P. (2024). The Nexus of Change Management and Sustainable Leadership: Shaping Organizational Social Impact. DIVERSITY, EQUITY AND INCLUSION, 184–197. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Barlou, O., & Beligiannis, G. N. (2021). Transformational Leadership and Digital Skills in Higher Education Institutes: During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerging Science Journal, 5(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Halkiopoulos, C., Antonopoulou, H. (2022). Neuroleadership an Asset in Educational Settings: An Overview. Emerging Science Journal. Emerging Science Journal, 6(4), 893–904. [CrossRef]

- O'Donovan, R., Rogers, L., Khurshid, Z., De Brún, A., Nicholson, E., O'Shea, M., ... & McAuliffe, E. (2021). A systematic review exploring the impact of focal leader behaviours on health care team performance. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(6), 1420-1443. [CrossRef]

- Razavi, N. S., Jalili, M., Sandars, J., & Gandomkar, R. (2022). Leadership behaviors in health care action teams: A systematized review. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 36. [CrossRef]

- Koutsopoulou, I., Grace, E., Gkintoni, E., & Olff, M. (2024). Validation of the Global Psychotrauma Screen for adolescents in Greece. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 8(1), 100384. [CrossRef]

- Burr, H., & Berthelsen, H. (2019). The third version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Safety and Health at Work, 10(4), 482-503. [CrossRef]

- Nübling, M., & Burr, H. (2014). COPSOQ International Network: Co-operation for research and assessment of psychosocial factors at work. Public Health Forum, 22(1), 18.e1-18.e3. [CrossRef]

- Dicke, T., & Marsh, H. W. (2018). Validating the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ-II) using Set-ESEM: Identifying psychosocial risk factors in a sample of school principals. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 584. [CrossRef]

- Rosário, S. A. (2017). The Portuguese long version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire II (COPSOQ II) – a validation study. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 12, 24. [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, A., & Shukla, P. (2019). Dissecting the effect of workplace exposures on workers’ rating of psychological health and safety. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 62(5), 412-421. [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T. S., Hannerz, H., Høgh, A., & Borg, V. (2005). The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire—a tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 31(6), 438-449. [CrossRef]

- Pejtersen, J. H., Kristensen, T. S., Borg, V., & Bjorner, J. B. (2010). The second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 38(3 suppl), 8-24. [CrossRef]

- Lincke, H. V., & Theorell, T. (2021). COPSOQ III in Germany: Validation of a standard instrument to measure psychosocial factors at work. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology, 16, 50. [CrossRef]

- Berthelsen, H., Westerlund, H., Bergström, G., & Burr, H. (2020). Validation of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire Version III and establishment of benchmarks for psychosocial risk management in Sweden. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 3179. [CrossRef]

- Şahan, C. B., & Aydın, H. (2018). A novel version of Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire-3: Turkish validation study. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health, 73(6), 354-362. [CrossRef]

- Naring, G., & van Scheppingen, A. (2021). Using health and safety monitoring routines to enhance sustainable employability. Work, 70(3), 959-966. [CrossRef]

- Kotsakis, N. e., & Nübling. (2018). Employability in the 21st Century. The Greek COPSOQ v.3 Validation Study, a post crisis assessment of the Psychosocial Risks (p. 63). Leuven, Belgium: Conference Book, 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Employability. [CrossRef]

- Kotsakis, A., Conceptual framework development and systemic modelling for the assessment of strategic organizational change in public sector entities, PhD. Thesis,2019, University of Piraeus, Greece. [CrossRef]

- Kotsakis, A., & Avraam, D. (2024). The COPSOQ III Greek validation study [Data set]. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Rizopoulos, D. (2006). ltm: An R package for latent variable modelling and item response theory analyses. Journal of Statistical Software, 17(5), 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Gamer, M., Lemon, J., Fellows, I., & Singh, P. (2012). Various Coefficients of Interrater Reliability and Agreement. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/irr/irr.pdf.

- Steiner, M., & Grieder, S. (2020). EFAtools: An R package with fast and flexible implementations of exploratory factor analysis tools. Journal of Open Source Software, 5(53), 2405. [CrossRef]

- Nardi, D. A., & Gyurko, C. C. (2013). The global nursing faculty shortage: Status and solutions for change. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 45, 317-326. [CrossRef]

- Hasselhorn, H. M., & Müller, B. H. (2005). Nursing in Europe: Intention to leave the nursing profession. NEXT Scientific Report, 17-24.

- de Oliveira, D. R., Griep, R. H., & Rotenberg, L. (2017). Intention to leave profession, psychosocial environment and self-rated health among registered nurses from large hospitals in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Services Research, 17, 21. [CrossRef]

- Derycke, H., Vlerick, P., & Clays, E. (2010). Impact of the effort-reward imbalance model on intent to leave among Belgian health care workers: A prospective study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 879-893. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H., While A. E., & Barriball, K. L. (2005). Job satisfaction among nurses: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 42, 211-227. [CrossRef]

- Ellenbecker, C. H., & Porell, F. W. (2008). Predictors of home healthcare nurse retention. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 40, 151-160. [CrossRef]

- Dall’Ora, C., Ball, J., Recio-Saucedo, A., & Griffiths, P. (2020). Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Human Resources for Health, 18, 41. [CrossRef]

- Bargagliotti, A. L. (2012). Work engagement in nursing: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(6), 1414-1428. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Barlou, O., Beligiannis, G. (2020). Leadership Types and Digital Leadership in Higher Education: Behavioural Data Analysis from University of Patras in Greece. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 19 (4), pp.110-129. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Kourkoutas, E.; Vassilopoulos, S.P.; Mousi, M. Clinical Intervention Strategies and Family Dynamics in Adolescent Eating Disorders: A Scoping Review for Enhancing Early Detection and Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4084. [CrossRef]

- del Carmen Giménez-Espert, M., Prado-Gascó, V., & Soto-Rubio, A. (2020). Psychosocial risks, work engagement, and job satisfaction of nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 8. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E. (2023). Clinical neuropsychological characteristics of bipolar disorder, with a focus on cognitive and linguistic pattern: a conceptual analysis. F1000Research, 12, 1235. [CrossRef]

- Malliarou, M., & Kotsakis, A. (2023). Editorial: Psychosocial work environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1272290. [CrossRef]

- Berthelsen, H., Westerlund, H., Bergström, G., & Burr, H. (2020). Validation of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire Version III and establishment of benchmarks for psychosocial risk management in Sweden. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3179. [CrossRef]

- Tzenetidis, V., Kotsakis, A., Gouva, M., Tsaras, K., & Malliarou, M. (2023). The relationship between psychosocial work environment and nurses' performance, on studies that used the validated instrument Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ): An empty scoping review. Polski Merkuriusz Lekarski, 51(4), 417-422. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).