1. Introduction

"Hæmorrhagiam cohibere." (Stopping bleeding)

After each dental surgical treatment, slight bleeding is typically observed. This bleeding is capillary in nature and usually stops permanently within a few minutes, following the formation of a blood clot. However, when bleeding persists beyond the normal 3-5 minute timeframe or resumes after initially stopping, it is considered a hemorrhage, a complication that can significantly impact the surgical outcome and patient recovery.

Hemorrhage can be categorized into two types: early (primary) and late (secondary). Primary hemorrhage occurs immediately after surgery, while secondary hemorrhage can occur hours or even days post-operatively. Effective management of such bleeding is crucial to ensure a clear surgical field, reduce the risk of post-operative complications, and promote optimal healing. The use of local hemostatic agents has become an essential strategy in oral surgery, providing targeted methods to control bleeding efficiently.

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across several electronic databases, including Medscape, PubMed-Medline, Science Direct, and EBSCO Host, to identify relevant publications on local hemostatic agents in oral surgery. The search covered the period from 1990 to 2023. Specific keywords used in the search included "local hemostasis," "bleeding," "oral surgery," "tranexamic acid," "gelaspon," and "fibrin sealants."

A total of 46 publications were identified and selected based on their relevance to the topic. These publications were then thoroughly reviewed to extract information on the efficacy, safety, and practical applications of various hemostatic agents. The data gathered from these studies provide a foundation for understanding the role of local hemostatic agents in enhancing surgical outcomes and patient care in oral surgery.

3. Local Haemostatic Measurments

Bleeding can result from various risk factors, which are categorized into general and local factors. Understanding these risk factors is essential for selecting appropriate hemostatic agents and strategies to manage bleeding during and after dental procedures. The primary risk factors contributing to bleeding include:

General factors that contribute to bleeding may include:

- -

Uncontrolled hypertension;

- -

Alcoholism and cirrhosis;

- -

Diabetes;

- -

Systemic disorders related to impaired blood coagulability or diseases of vessel walls (hemorrhagic diatheses) such as hemophilia, hemorrhagic vasculitis, von Willebrand disease, Rendu-Osler disease, and vitamin C and K deficiencies

- -

Diseases presenting with hemorrhagic syndromes, including acute leukemia, hepatitis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, septic endocarditis, typhus, and scarlet fever;

- -

Intake of anticoagulants such as aspirin, clopidogrel, ticagrelor, cangrelor, tyrofiban, and antiplatelet agents like acenocoumarol (Sintrom), warfarin, dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban;

- -

Hormonal hemorrhages, including hemorrhagic metropathy and menopause [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

Local factors include:

- -

Acute inflammation in the area of the extracted tooth;

- -

The extent of the surgical trauma inflicted;

- -

Soft tissue tearing.

A large number of clinical studies demonstrate the effectiveness of local hemostatic agents in achieving adequate hemostasis after dental surgery, particularly in patients with impaired hemostasis [

9,

11,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Local hemostatic agents that can be used in the field of oral surgery are:

1. 10-20% Sodium Chloride solution (saline)

A hypertonic solution of sodium chloride (saline) has long been used as a hemostatic agent. 10-20% sodium chloride solution is applied through mechanical compression using sterile gauze. Its haemostatic effect causes an influx of tissue fluid into the blood vessel, which carries tissue thromboplastin. Also it induces slight haemolysis of erythrocytes and platelets, releasing thromboplastic substances that enhance the action of endogenous thromboplastin [

9].

2. Hydrogen Peroxide solution 3-6%

Hydrogen peroxide solution (H₂O₂,

Figure 1) exhibits vasoconstrictive activity through various mechanisms. These mechanisms include increasing Ca²⁺ influx from intracellular stores in smooth muscle cells, forming cyclooxygenase-derived prostanoids, activating enzymes, activating potassium (K⁺) channels, and generating hydroxyl radicals. In dental surgery, it can be applied using sterile gauze [

20].

3. Aprotinin (Trasylol, Gordiox)

Aprotinin is a polyvalent protease inhibitor with antifibrinolytic action that inactivates plasmin, trypsin, alpha-chymotrypsin, and kininogenases (

Figure 2). In dental practice, it can be used for local hemostasis by applying 100,000 KUI of aprotinin on a sterile gauze.

Adverse Drug Reactions: Local thrombophlebitis, allergic reactions, hypotension (low blood pressure), tachycardia (rapid pulse), thrombophlebitis at the injection site, myalgia, bronchospasm, hallucinations, impaired mental activity.

Drug Interactions: Aprotinin should not be combined with dextran.

Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to aprotinin.

Dosage Regimen: Administered intravenously in the form of an infusion [

21,

22].

4. Adrenaline

Adrenaline (also known as epinephrine) in a concentration of 0.1% per 1 ml can be used for local haemostasis applied on sterile gauze.

Adrenaline is a sympathomimetic agent that acts on adrenergic receptors. It stimulates alpha and beta-adrenergic receptors, resulting in effects such as vasoconstriction, increased heart rate, increased cardiac output, bronchodilation, and inhibition of histamine release.

Contraindications: Adrenaline should be used with caution or avoided in patients with severe hypertension, hyperthyroidism, and certain types of heart disease (e.g., coronary artery disease, arrhythmias) unless specifically indicated and monitored by a healthcare professional.

Adverse Effects: Common adverse effects of adrenaline include palpitations, tachycardia, hypertension, anxiety, tremor, headache, and sweating [

23].

Figure 3.

Adrenaline ampoules 0.1% 1 ml.

Figure 3.

Adrenaline ampoules 0.1% 1 ml.

5. Etamsylate (Dicynone)

Etamsylate is used to treat and prevent bleeding or haemorrhage.

Etamsylate is a hemostatic agent that works by stabilizing and strengthening blood vessel walls, which helps in reducing bleeding. It also promotes platelet adhesion and aggregation, enhancing the clotting process (

Figure 4).

Contraindications: Etamsylate should be used with caution or avoided in patients with a history of hypersensitivity or allergic reactions to the drug and in patients with thromboembolic disorders or active arterial thrombosis [

24,

25].

6. Aminocaproic Acid

Aminocaproic acid is chemically similar to the amino acid lysine and is a synthetic inhibitor of fibrinolysis (

Figure 5). As a structural analog of the enzyme, it competitively inhibits the action of enzymes such as plasmin and plasminogen activators, which bind via lysine residues. It is used for bleeding resulting from fibrinolytic therapy or as additional therapy in haemophilia. In dentistry can be used topically.

Adverse Effects: Aminocaproic acid may cause hypotension (low blood pressure), stomach discomfort, diarrhea, nasal congestion, and intravascular thrombosis. Its use is contraindicated in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [

26].

7. Epsylone-Aminocaproic Acid (EAC)

Reduces fibrinolysin activity and interferes with fibrin degradation. Can be used in the form of 15% gargling solution [

26].

8. Paraaminomethylbenzoic Acid (PAMBA)

Pambenzacide 10 mg/ml in 5 ml ampoules, available in boxes of 10 or 50 ampoules.

Pambenzacid is a medication containing paraaminomethylbenzoic acid and belongs to the group of antifibrinolytic agents (

Figure 6). It suppresses factors involved in blood clotting (various kinases), thereby preventing the breakdown of blood clots (antifibrinolytic effect). PAMBENZACID® is used for local bleeding due to increased fibrinolysis, such as bleeding after tonsillectomy, dental procedures, local bleeding during adenoidectomy, other urological and gynecological surgeries, and in patients with hemophilia A and B, von Willebrand disease, and von Willebrand-Jürgens syndrome. It is also used in cases of overdose with anticoagulants.

In cases of overdose with fibrinolytics (such as streptokinase, urokinase, fibrinolysin), PAMBENZACID® is used to counteract their effects (antidote) [

26,

27,

28].

9. Gelatin

Gelatin is a hydrocolloid obtained from partial hydrolysis of purified animal collagen. It is presented as a gelatin sponge, powder (mixed to form a paste), or film. Gelatin can be used dry or after moistening with a physiological solution.

A gelatin hemostatic sponge absorbs blood along with the formed elements and platelets. It increases the formation of active thromboplastin, leading to the formation of a massive clot that incorporates the gelatin sponge. It can be combined with other hemostatic agents [

1,

15,

29,

30].

Commercial Products Available:

9.1. Gelfoam® is an Absorbable Gelatine Powder from Absorbable Gelatin Sponge, USP.

Gelfoam® is derived from purified porcine (pig) skin gelatin (

Figure 7). It has the ability to absorb many times its weight in whole blood. GELFOAM Sterile Powder, saturated with sterile sodium chloride solution, is indicated in surgical procedures, including those involving cancellous bone bleeding, as a hemostatic device, when control of capillary, venous, and arteriolar bleeding by pressure, ligature, and other conventional procedures is either ineffective or impractical. Although not necessary, GELFOAM can be used either with or without thrombin to obtain hemostasis. When not used in excessive amounts, GELFOAM is absorbed completely, with little tissue reaction within 4-6 weeks [

29,

30].

Mahmoudi A end al. extracted two mandibular molar teeth in 26 patients and recorded the amount of bleeding for 1 and 4 h. They concluded that Gelfoam is recommended for use in dental surgeries because of its abilities in bleeding, pain, and dry socket control [

31].

9.2. Surgispon®: Tampon Dimensions: 80 x 50 x 10 mm, Packaged in sets of 10

Surgispon® is a resorbable, hemostatic, gelatin sponge designed for hemostatic use by applying it to a bleeding surface (

Figure 8). Surgispon® is a hemostatic sponge manufactured from highly purified premium-grade gelatin material for use in surgical procedures. When implanted in vivo in appropriate quantities, it is completely absorbed within 3-4 weeks. Applied to bleeding mucosal areas, it liquefies within 2 to 5 days. Surgispon® gelatin sponges have a porous structure that activates platelets as soon as blood comes into contact with the sponge matrix, allowing them to act as a catalyst in fibrin formation.

Indications: Surgispon® can be effectively used for hemostasis in a variety of surgical procedures to control capillary, venous, or arterial bleeding by pressure.

Contraindications: Surgispon® should not be used in patients with known allergies to collagen; in combination with methyl methacrylate adhesives; in cases of blood leakage; for primary treatment of coagulation disorders; in the presence of infection. When applied to mucosal surfaces, Surgispon® can be left in place until it liquefies [

11,

29,

30].

9.3. Caprogel®: is a lyophilized sterile gelatin sponge in strips measuring 60/60 mm and 60/120 mm.

Caprogel® is a sterile resorbable hemostatic sponge containing medical gelatin, epsilon-aminocaproic acid, nitroxoline, and others (

Figure 9). When applied locally to superficial wounds and during surgical interventions for parenchymal and capillary bleeding, the preparation stimulates blood clotting and stops bleeding. It is absorbed within approximately 30 days and does not cause allergic or toxic reactions.

Indications: Caprogel® is used as a local hemostatic agent for parenchymal and capillary bleeding during surgical interventions in neurosurgery, thoracic, abdominal, and maxillofacial surgery, gynecology, and urology [

30].

10. Gelatin Hemostatic Sponge

Gelaspon®: Each 100 mg contains 100 mg of gelatin (from pork). It is a local hemostatic agent in the form of a gelatin absorbable sponge (

Figure 10).

Gelaspon is a collagen-based hemostatic sponge used for controlling bleeding in surgery and medicine. This sponge is made from a large amount of collagen, which is a bioactive material known for its hemostatic properties. Gelaspon is applied as a compress or sponge on the bleeding surface, where it absorbs blood and stops bleeding by stimulating the coagulation process. After application, Gelaspon degrades in the tissues and is absorbed by the body relatively quickly [

1,

15,

20,

30].

Gelaspon has multiple medical applications, including in surgical procedures to control bleeding, wound healing and other medical conditions where bleeding control is essential.

Dosage and Administration: A suitable-sized piece of the product is cut with sterile scissors and placed on the bleeding site. The sponge can be applied dry or slightly moistened with sterile saline solution or freshly prepared thrombin solution in distilled water [

30].

11. Collagen Hemostatic Sponge (Tachocomb, Hemocollagene)

11.1. Tachocomb

Contains collagen extracted from horse tendons and coated with human fibrinogen, bovine thrombin, and bovine aprotinin (

Figure 11). Upon contact with bleeding tissues, coagulation factors in the product dissolve and, together with collagen, cover the lesions. Thrombin converts fibrinogen into fibrin, providing coverage of the wound surface along with polymerized collagen. Aprotinin prevents the plasmin-mediated lysis of the fibrin cover [

30].

11.2. Caprocol®: Lyophilized Collagen Sponge in Strips of 60/60 mm and 60/120 mm

Caprocol is a sterile resorbable sponge consisting of fibrillar collagen, epsilon-aminocaproic acid, nitroxoline, and excipients. It has a local hemostatic effect on superficial parenchymal and capillary bleeding. It is resorbed within 60 days without causing toxic or allergic reactions.

Indications: Applied during surgical interventions for superficial parenchymal and capillary bleeding in neurosurgery, thoracic, abdominal, cardiovascular, maxillofacial surgery, gynecology, urology, and others [

30].

12. Surgicel, Oxysell

Consists of an oxidized cellulose polymer (polyanhydroglucuronic acid), introduced into clinical practice in 1947, is widely used in oral and maxillofacial surgery to control intraosseous arterial bleeding [

48,49]. Halfpenny W et al [

28] did a randomized trial with 46 patients taking warfarin with INR 2-4.1. For local hemostasis, use oxycellulose (Surgicel) or fibrin glue (Beriplast). They reported 2 cases of bleeding after 24 hours. They concluded that in patients with an INR within the therapeutic range, fibrin glue was as effective as oxycellulose. The single patient requiring hospitalization for hemorrhage had the most extracted teeth (6), the longest procedure (60 minutes), and was one of the oldest patients (81.8 years) [

30].

Lillis T et al. [

41] published a study of 111 patients taking aspirin (42), clopidogrel (36), and aspirin and clopidogrel (42). They reported 66.7% bleeding in the first 30 minutes after extraction in patients with dual antiplatelet therapy, 2.6% with aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapy, and 0.4% in the control group, differences that were statistically significant. All complications were successfully managed with oxycellulose (Surgicel) and suture. No patient developed late hemorrhage.

Morimoto Y. et al. [

12] extracted 513 teeth in 306 visits in 270 patients. 134 of the patients were taking warfarin, 49 a combination of warfarin with an antiplatelet agent, and the remaining 87 an antiplatelet agent alone. In patients on warfarin, the INR was 1.5 - 3.7. Oxidized cellulose and suture were used.

13. Alveo Penga

Container containing 30 g of paste (

Figure 12) mixture of Penghawar Djambi: 4g per 100g, Iodoform: 10g per 100g, Butoform: 4g per 100g, Excipients q.s.p. 100g.

Alveo-Penga is a haemostatic agent through mechanical action: it facilitates clot formation (absorption properties of Penghawar Djambi) and also acts protectively at the operative site. Additionally, contains Iodoform: an antiseptic whose action is particularly effective on mucous membranes and wounds. It helps prevent any possibility of infection such as alveolitis and Butoform: a local contact anesthetic that reduces postoperative pain. It is used as a surgical haemostatic dressing after tooth extraction.

Contraindications: Known allergy to iodine or its derivatives and to local anaesthetics of the ester type [

32].

14. Dry Thrombin

Thrombin is also known as activated Factor II in blood clotting. It converts fibrinogen into its active form, from which fibrin is synthesized, and it plays a significant role in platelet activation and the formation of a fibrin clot. It has an antagonistic effect against the action of vitamin K antagonists.

It is obtained from human and bovine blood and is presented as a whitish powder in ampoules of 500-5000 IU. Before use, it is dissolved in saline solution/distilled water to a concentration of 100-1000 IU per cubic centimeter. The dissolved thrombin loses its activity after 24 hours. Saturated gauze is applied to the bleeding area for 5-10 minutes [

34,

35].

15. Fibrin Sealants (Fibrin Glues)

Fibrin sealants, also known as fibrin glues, are hemostatic agents used in surgical procedures to promote hemostasis and tissue adhesion. They are composed of fibrinogen and thrombin, which react together to form a fibrin clot upon application to tissues. These sealants mimic the final stages of the blood coagulation cascade.

Application: Fibrin glue is applied topically to tissues during surgery. The components are typically stored separately and mixed just before application to ensure optimal activity. The mixture is applied directly to the surgical site, where it rapidly forms a fibrin clot, sealing tissues and promoting hemostasis.

Indications: Used in various surgical procedures, including cardiovascular, orthopedic, general, and plastic surgery; Particularly useful in surgeries involving tissues with high bleeding risk or requiring precise tissue adhesion [

35,

36].

Monitoring for allergic reactions, although these are rare with fibrin sealants.

15.1. Tissel

- -

-

Component 1: Human fibrinogen (as a clotting protein): 91 mg/ml

Aprotinin (synthetic): 3000 KIU/ml

Excipients: Polysorbate 80: 0.6 – 1.9 mg/ml

- -

-

Component 2: Thrombin solution:

Human thrombin: 500 IU/ml

Calcium chloride: 40 µmol/ml

Use: To prepare the fibrin sealant for use, mix 1 ml, 2 ml, or 5 ml of Human fibrinogen with 1 ml, 2 ml, or 5 ml of thrombin solution (containing calcium chloride), to obtain a ready-to-use solution of 2 ml, 4 ml, or 10 ml.

This combination results in the activation of fibrinogen by thrombin, leading to the formation of a fibrin clot at the site of application. The addition of calcium chloride helps in stabilizing the fibrin clot formation by enhancing the enzymatic action of thrombin on fibrinogen.

Indications: Used in surgical procedures where rapid hemostasis and tissue sealing are required, particularly in cardiovascular, orthopedic, and general surgery; Effective for controlling bleeding from small vessels and ensuring tissue adhesion and closure [

35,

36].

15.2. Tissucol

- -

- Clotting protein: 75 – 115 mg, of which 70 – 110 mg is fibrinogen

- -

Plasma fibronectin: 2 – 9 mg

- -

Factor XIII: 10 - 50 U

- -

Plasminogen: 0.04 - 0.12 mg

- -

Aprotinin: 3000 KIU/ml (bovine solution)

- -

Lyophilized human plasma

Usage:

Tissucol is used as a fibrin sealant in surgical procedures to promote hemostasis and tissue sealing. It combines various clotting factors and proteins to mimic the final stages of the body's clotting cascade, facilitating the formation of a fibrin clot to seal tissues.

Indications: Effective for controlling bleeding in cardiovascular, orthopedic, and general surgical procedures; Used for tissue adhesion and closure in various surgical specialties.

Monitor for signs of allergic reactions or adverse events during and after application. Tissucol acts by mimicking the natural clotting process, combining fibrinogen with thrombin and other clotting factors to form a stable fibrin clot at the site of application [

36,

37].

15.3. Beriplast

Kit 1: Human Fibrinogen Concentrate and Aprotinin Solution (

Figure 15).

This kit consists of:

- -

1 vial of human fibrinogen concentrate (powder): Contains 45 mg of human fibrinogen and 30 IU of human Factor XIII.

- -

1 vial of aprotinin solution: Contains 500,000 KIU (Kallikrein Inhibitor Units) of aprotinin.

Kit 2: Human Thrombin and Calcium Chloride Solution. This kit consists of:

- -

1 vial of human thrombin (powder): Contains 250 IU of human thrombin.

- -

1 vial of calcium chloride solution: Contains 2.95 mg of calcium chloride dihydrate.

These kits contain components commonly used in surgical and hemostatic procedures to promote blood clotting and wound closure. The human fibrinogen and thrombin components work together to form fibrin, a crucial component of blood clots. Fibrin glues (Tissel, Beriplast) imitate the conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin [

36,

37,

38], but due to a number of disadvantages (taking blood from the patient, allergic reactions and high cost) they are not widely used in dental practice.

Bodner L. et al. [

39] concluded that they are safe and can be used in dental extraction at INR up to 5.0 and in surgical trauma in the range of 1 to 12. Similar results were published by Zusman SP and Martinowitz U [

40,

41].

Aprotinin is included to inhibit fibrinolysis (the breakdown of clots). The addition of calcium chloride facilitates the activation of thrombin and the cross-linking of fibrin, aiding in the clotting process. These kits are utilized to manage bleeding and promote hemostasis in various surgical settings.

Due to their high cost, tissue adhesives are challenging to implement in dental practice [

38].

16. Acidum Tranexamicum

Tranexamic Acid (

Figure 16) is indicated for Prevention and treatment of bleeding due to general or local fibrinolysis in adults and children aged one year and older.

Dosage and Administration: When used as a mouthwash, 10 ml should be held in the mouth for two minutes. Rinse should be repeated four times a day for 2-5 days. The solution should not be swallowed. After using the solution, refrain from eating for one hour. If bleeding persists, gauze soaked in the solution can be applied and pressed against the bleeding area.

Due to its high cost, it is also not widely applicable in dental practice.

This mouthwash formulation of tranexamic acid is designed for the prevention and management of bleeding associated with fibrinolysis. It is administered through oral rinsing and is not intended for ingestion. The mouthwash protocol should be followed as directed by a healthcare professional to effectively manage bleeding episodes [

44,

45].

Cardona-Tortajada et al. [

33] extracted 222 teeth in 155 patients taking antiplatelets, 26 of whom had minor bleeding successfully controlled with tranexamic acid (Amchafibrin). Similar results were published by other authors [33,34,35.36.37].

Due to its high price, Tranexamic Acid mouthwash is not widely applicable in the dental practice [

33,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

17. Surgical Suturing (Sutura Chirurgica)

Figure 17.

Atraumatic sutures.

Figure 17.

Atraumatic sutures.

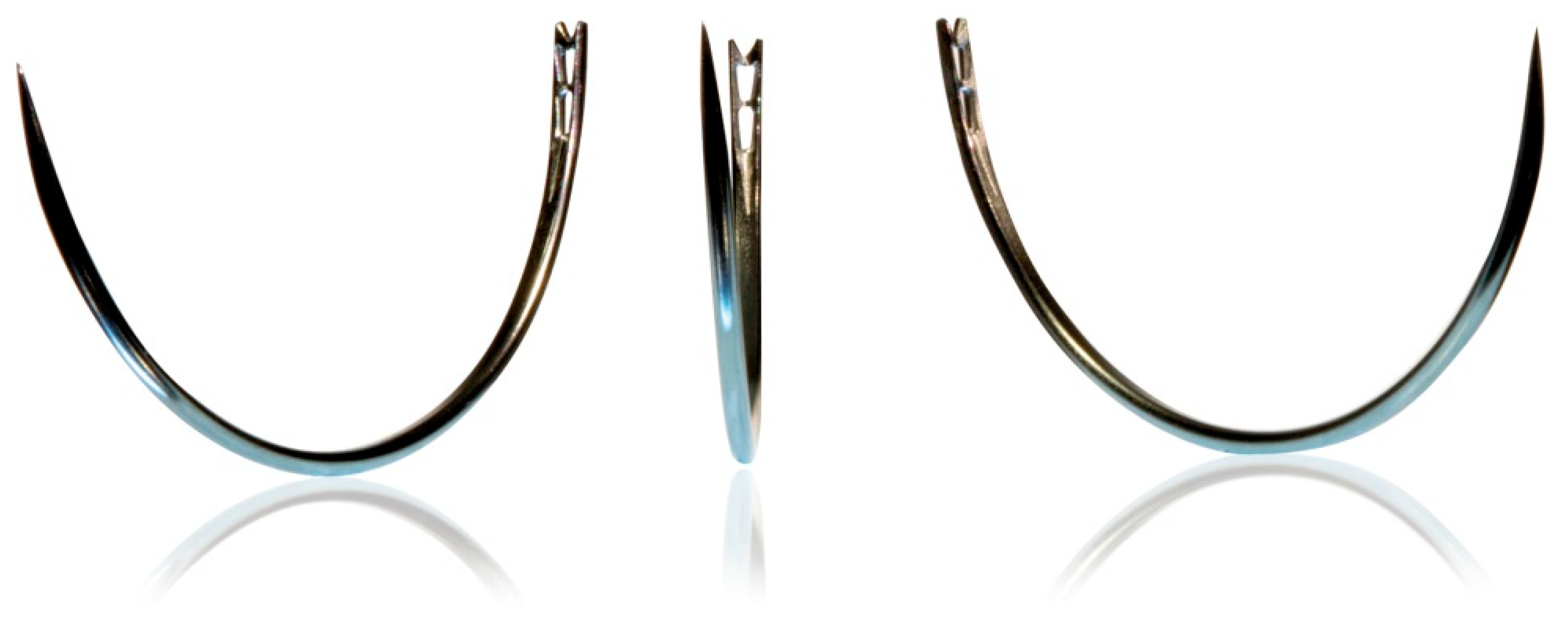

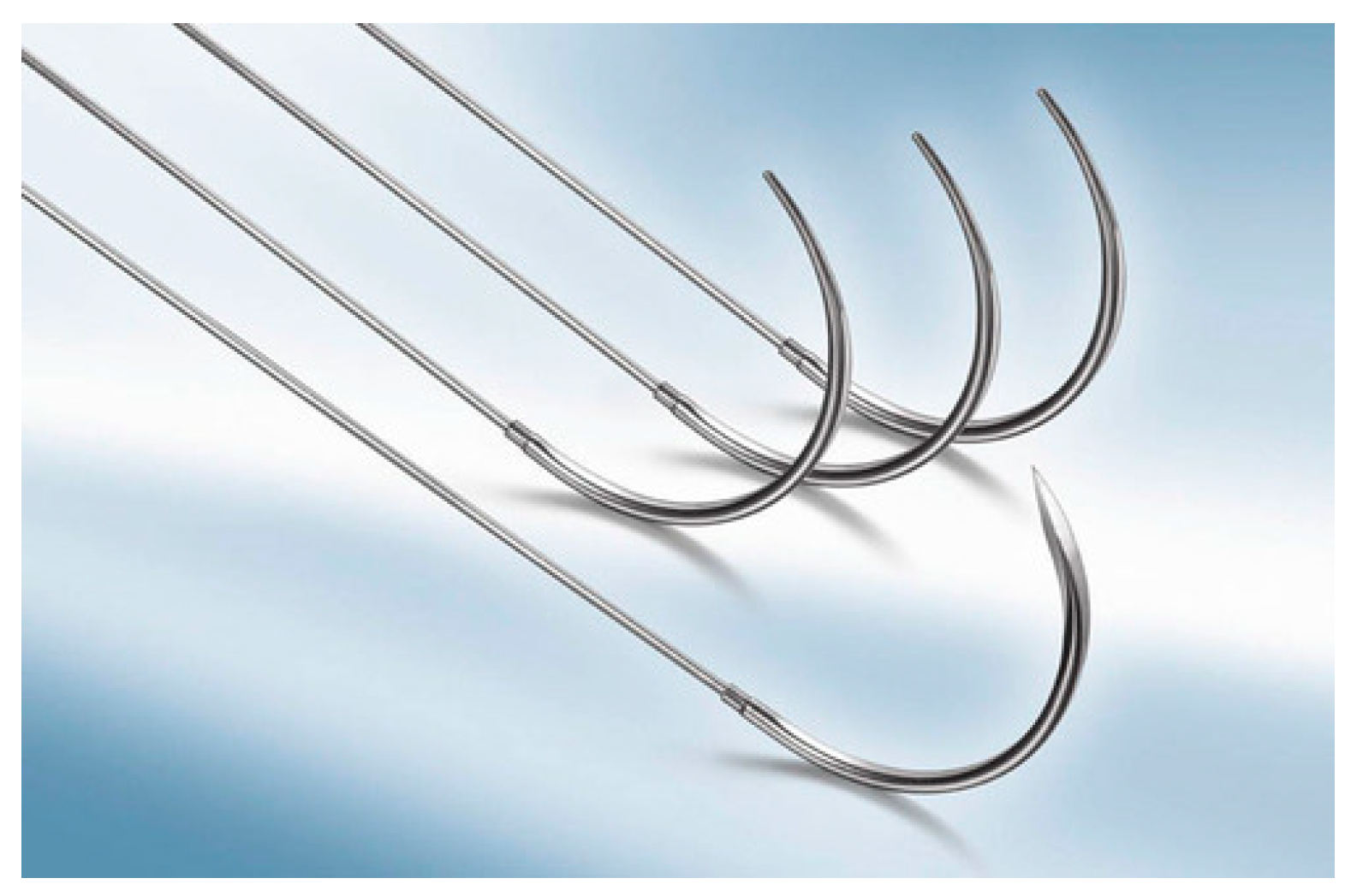

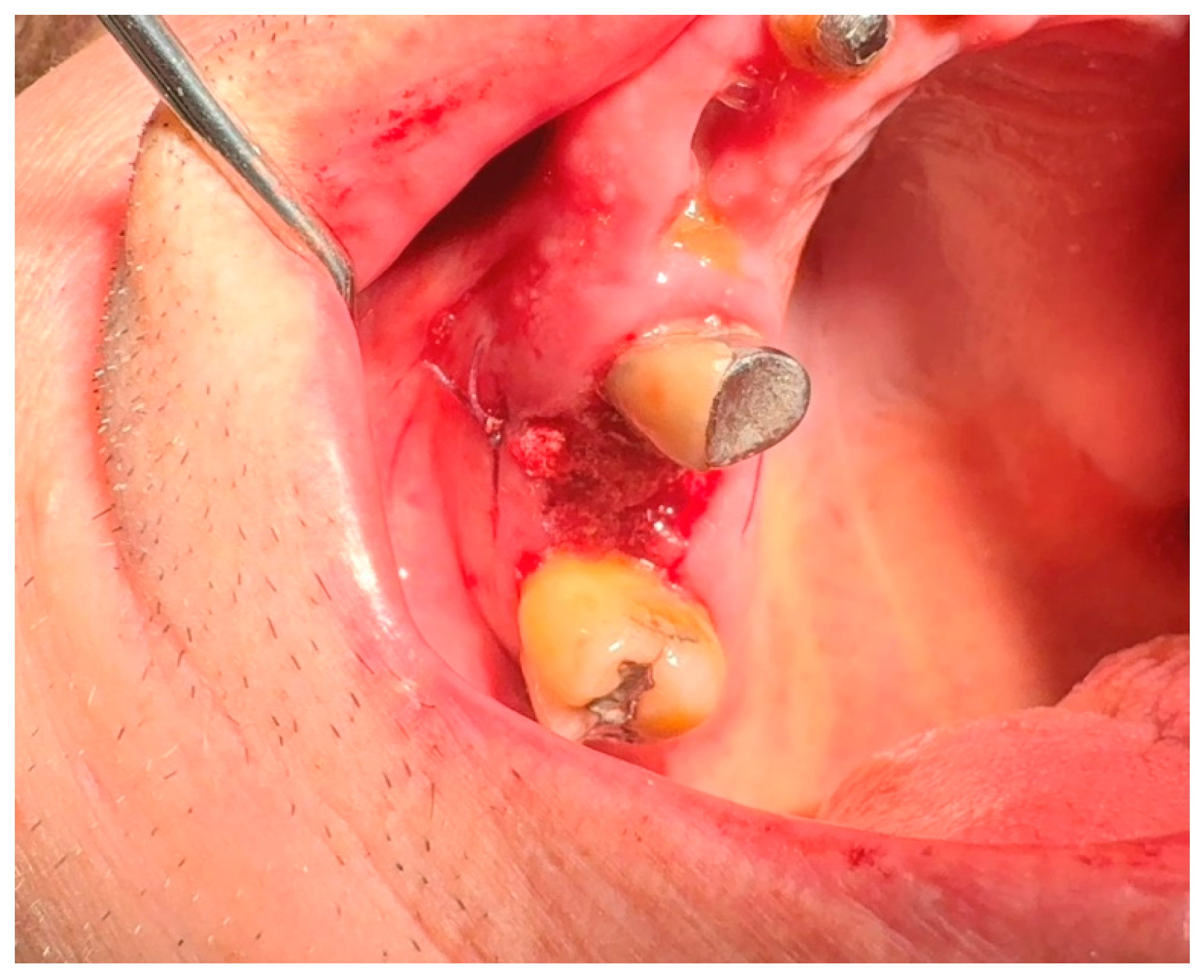

Surgical suturing is performed using surgical needles and sutures.

Suture needles are available in wide range from small to large. Tips can be in round form like sewing needle or in triangle form (

Table 1).

This type of needle is supplied separately from the suture thread and has a hole through which the thread is passed (

Figure 18). The advantage of this type of needle is that it allows for various combinations of needles and threads. However, eyed needles cause trauma to the tissues they pass through because the part with the eye is wider than the rest of the needle, and the double end of the thread causes additional tissue abrasion [

46].

These needles do not have an eye, as the suture thread is factory-attached to the needle (

Figure 19). The main advantage of this type of surgical needle is that there is no need to thread the needle, and tissue trauma during suturing is minimized due to the absence of an eye on the needle and the double end of the thread [

46].

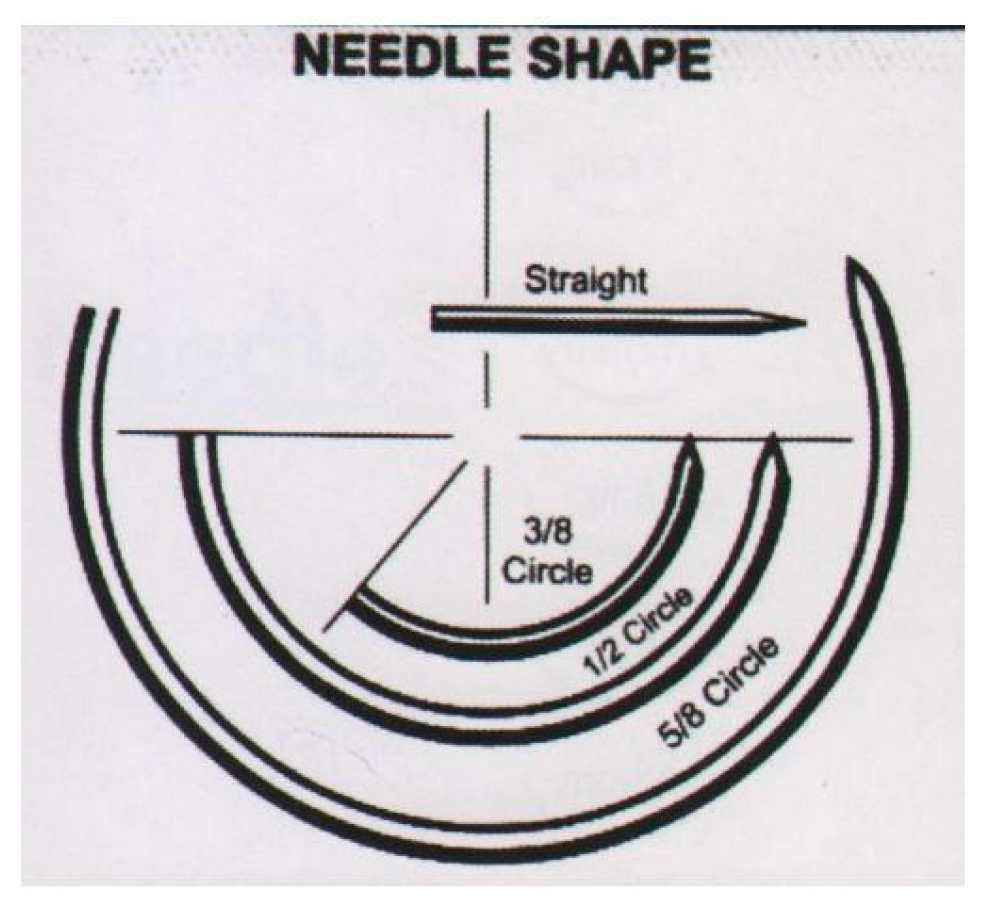

According the curvature of the needle: Curved type can be in 1/2, 1,4, 3/8, 5/8 or J shaped circle form (

Figure 20) [

46].

Surgical sutures, depending on the composition of the fibers, can be classified into monofilament and multifilament types. Monofilament sutures consist of a single filament, causing less tissue irritation when passing through, and they are less likely to serve as a reservoir for microbial growth. They are easy to tie but can break when stretched. On the other hand, multifilament sutures are composed of several intertwined fibers and are much stronger than monofilament sutures [

46].

Sutures can also be categorized based on their ability to be absorbed: absorbable and non-absorbable. Nowadays, absorbable synthetic sutures made from polyesters such as polyglycolic acid, Polyglycolide Lactic Acid, polyglyconate, and polidioxanonePolyglycolide Caprolactone are used. During their absorption (taking 40 to 119 days), they do not provoke a tissue reaction, unlike silk sutures used in the past, which caused inflammation as a "foreign body" [

46].

Non-absorbable sutures. These sutures are durable against proteolysis and hydrolysis. These sutures can have tension strength on 60th day. Non-absorbable suture types: silk, nylon polyamide (PA), polypropylene (PP), polyester polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), and stainless steel. They should be removed 7-10 days after placement [

46].

The thickness of suture material varies, with dental surgery mainly using atraumatic needles with suture material thickness ranging from 3/0 (0.20-0.249 mm) to 6/0 (0.07-0.099 mm) [

46].

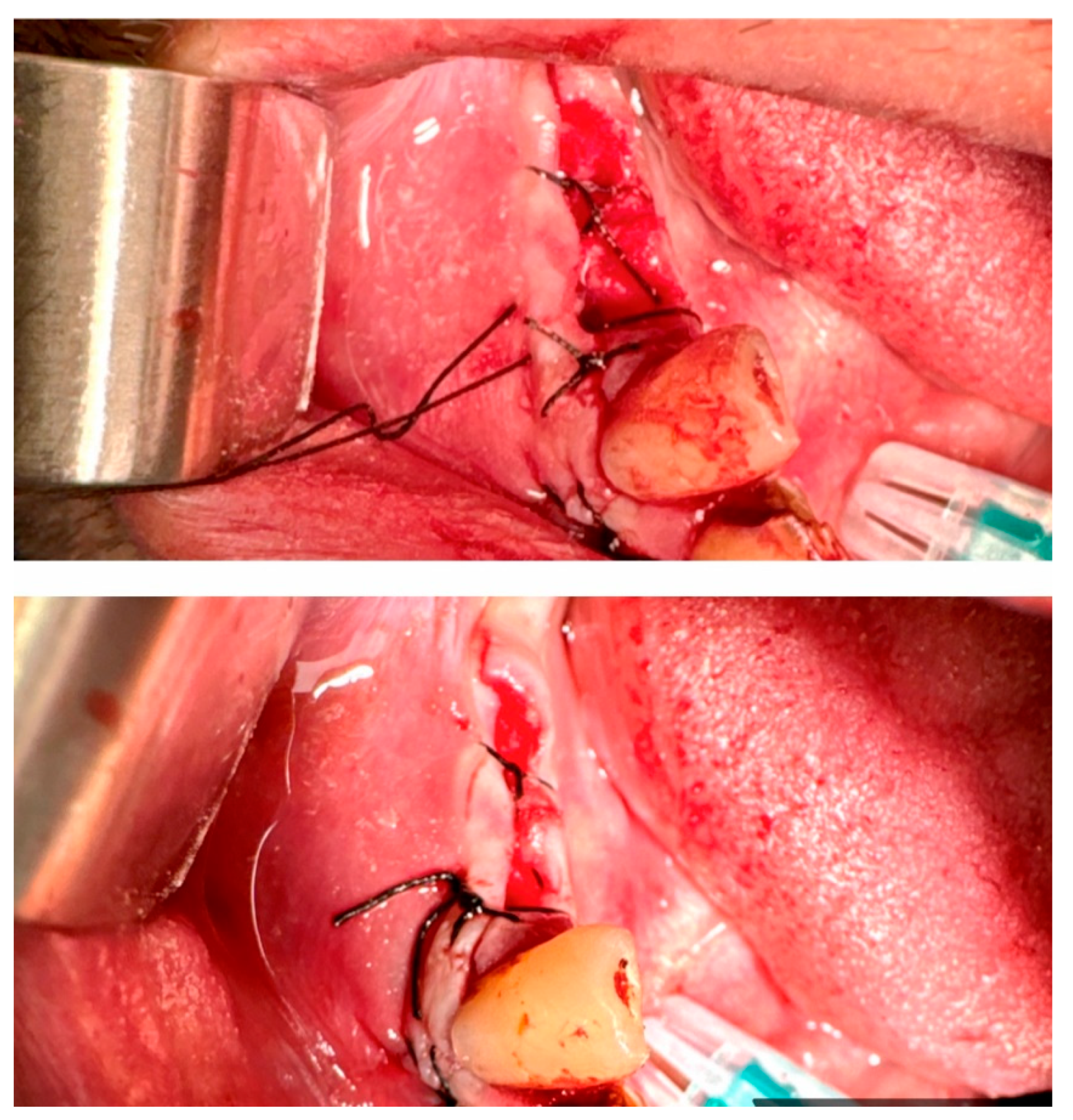

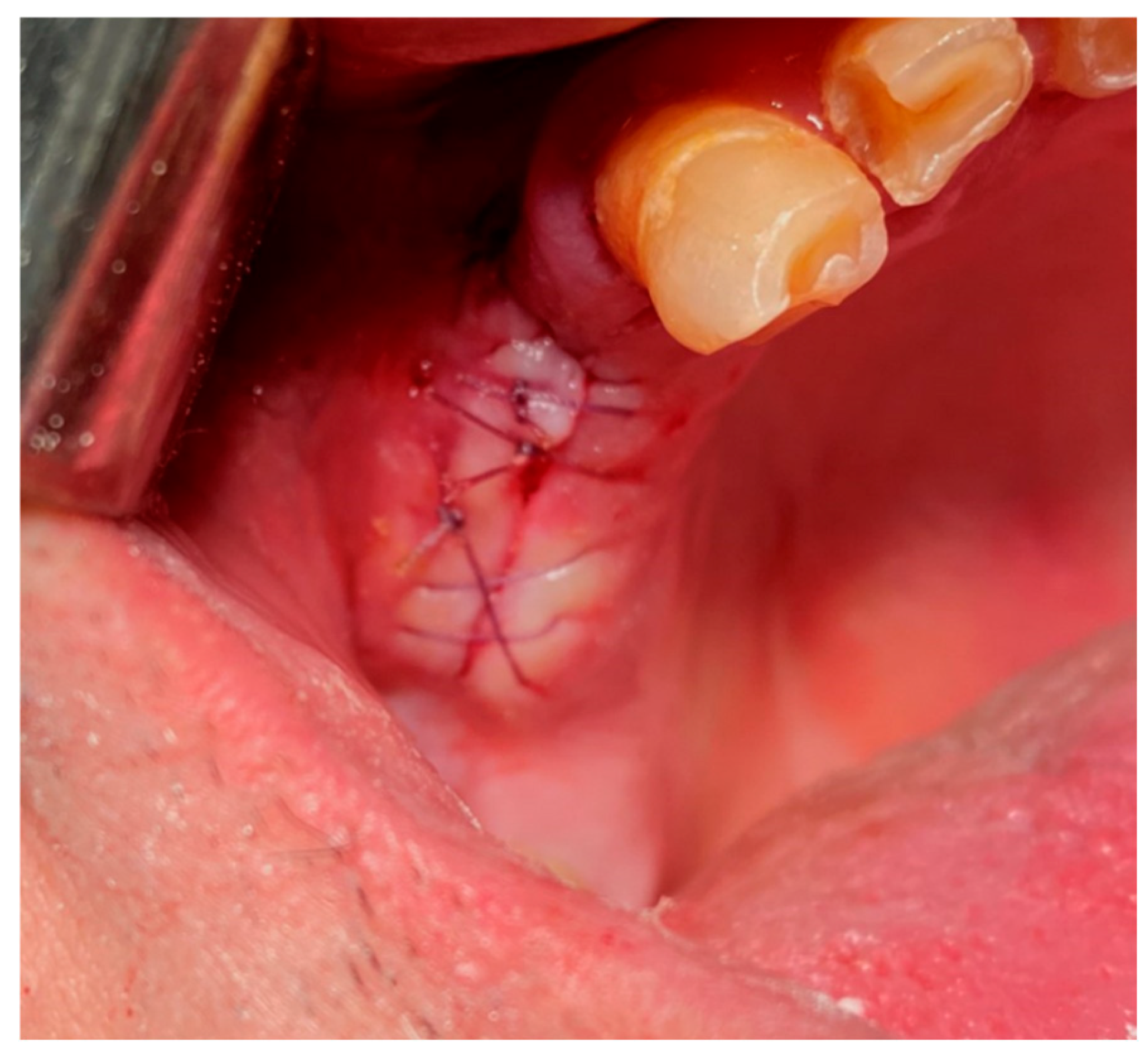

Surgical sutures can be executed in various ways:

1. Interrupted Suture:

-Single (vertical) interrupted suture is the most common suture technique within mouth cavity. Suture passes from one side of the wound, exits from the other side, and knotted at the top (

Figure 21) [

46,

47].

-Horizontal U-shape (mattress) suture is used to assist in local hemostasis after tooth extraction (

Figure 22). It tightens both sides of the wound (closing post-extraction wounds, covering intraosseous implants, etc.) [

46,

47].

-Horizontal U-shape locking suture: used for additional tightening of the wound ends (

Figure 23) [

46,

47].

- -

8 Figure Suture: This is a modified version of horizontal mattress suture (

Figure 24). While closing both side of the soft tissue, 8 sutures helps preserving the position of clot [

46,

47].

-Vertical Mattress Suture (Retentive Suture)

is applied in two stages especially on tissue on skin. Used for larger areas where additional support and tension control are needed. It involves placing deep, lateral bites that evert tissue edges for better wound edge alignment and strength [

46,

47].

2. Continuous Suture:

-Continuous Suture:

A continuous suture is used for long incisions, multiple extraction wounds or wound closures that require uniform tension distribution. The suture is made with a continuous series of stitches without knotting between each stitch [

46,

47].

-Simple Continuous Suture:

In this technique, the suture material is run continuously along the wound edge, forming a series of closely spaced stitches. It is efficient for closing long wounds quickly (

Figure 25) [

46,

47].

-Simple Continuous Locking Suture:

This variation of the continuous suture includes additional locking stitches at specific intervals to enhance wound closure and stability (

Figure 26) [

46,

47].

-Horizontal Mattress Suture:

The horizontal mattress suture is used to evert wound edges and distribute tension evenly across the wound. It involves placing bites of tissue on both sides of the wound, resembling the shape of a "mattress" [

46,

47].

-Horizontal Mattress Locking Suture:

Similar to the horizontal mattress suture, this technique includes locking stitches to secure the wound edges more effectively [

46,

47].

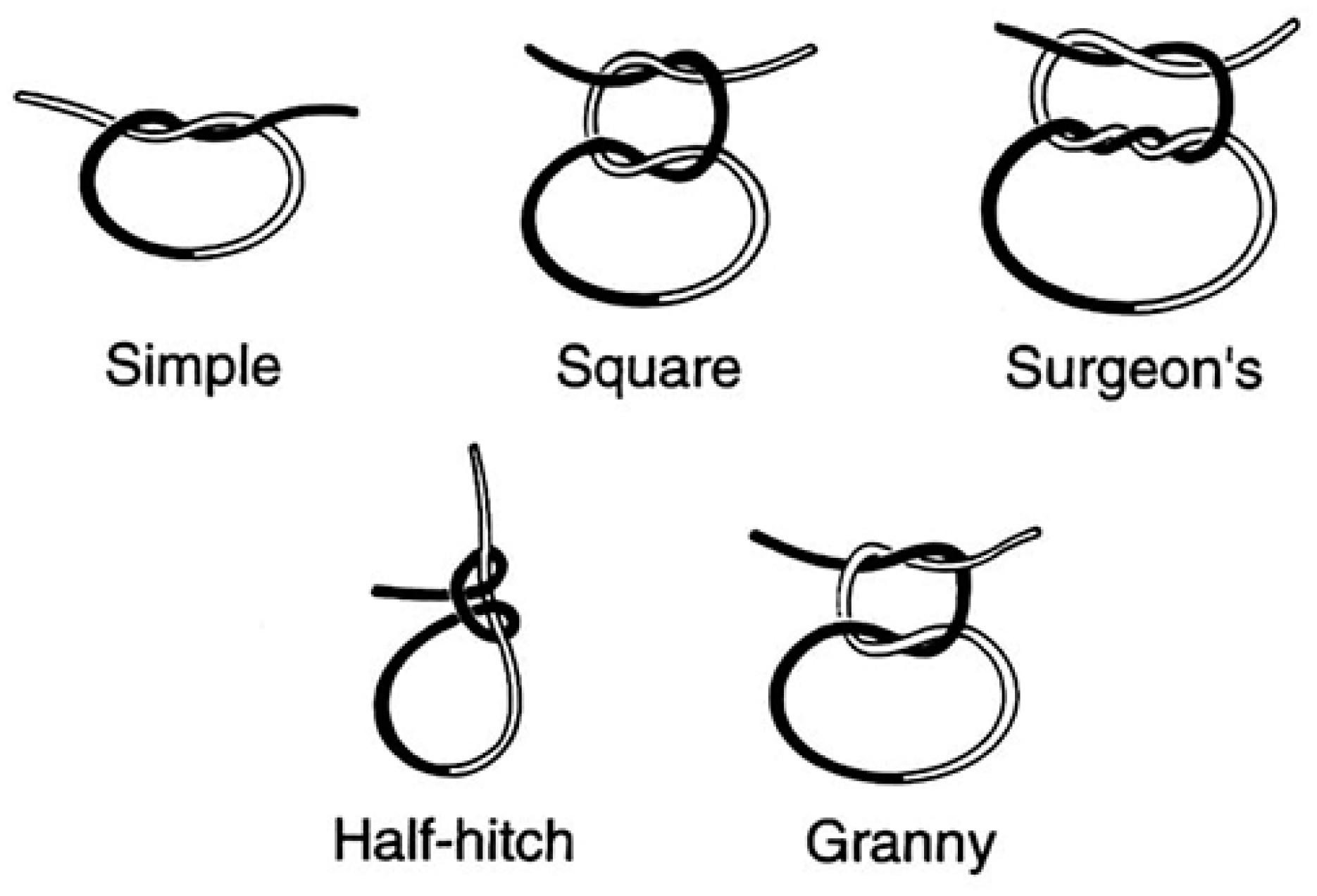

Once placed, sutures are secured by tying knots manually using surgical instruments (

Figure 27). Knots used in surgery can be simple (basic) or complex (multi-looped). Depending on the number of loops, knots can be:

Types of knots used in surgical suturing:

This is a simple knot with one loop around the suture material. It is quick to tie and provides basic security.

- -

Square Knot (Simple Knot, Granny Knot,

Figure 28):

The square knot is a basic knot used in surgery, consisting of two throws or loops. It is commonly used for secure wound closure.

- -

Surgeon's Knot (Two-Handed Knot, Double Throw Knot,

Figure 28):

The surgeon's knot is a more complex knot with additional throws or loops, designed to provide increased security and prevent loosening. It is commonly used in surgery for tying off sutures.

These knots are essential components of surgical suturing techniques and are selected based on the specific requirements of wound closure and tissue characteristics [

46,

47].

18. Black Tea

In addition to the standard post-operative instructions following dental surgery, if bleeding resumes, patients are instructed to apply pressure to the wound with a black tea bag for 20 minutes (

Figure 29).

Black tea is rich in tannins, which have hemostatic, astringent, and mild antiseptic effects that help prevent infection at the extraction site [

48].

19. Discussion

Local haemostatic agents play a crucial role in achieving haemostasis during dental surgical procedures as teeth extractions, periodontal surgeries, and implant placements. Various agents are employed, ranging from traditional methods like pressure and suturing to advanced materials such as oxidized cellulose, gelatin sponges, and fibrin sealants. The efficacy of local haemostatic agents is a paramount concern in clinical dentistry. Studies comparing different agents highlight variations in their ability to control bleeding promptly and sustainably.

Despite advancements, local haemostatic agents have inherent limitations. For instance, some agents may be difficult to handle or may not be suitable for patients with specific medical conditions or allergies. The duration of haemostasis achieved by different agents can also vary significantly, impacting the success of dental procedures and patient outcomes.

20. Conclusions

Local haemostatic agents are indispensable tools in contemporary dentistry, enabling clinicians to manage bleeding effectively and optimize treatment outcomes. However, their selection and application require careful consideration of factors such as efficacy, safety, and patient-specific considerations.

Conflicts of Interest

All Authors have seen and approved the manuscript being submitted. We warrant that the article is the Authors' original work. We warrant that the article has not received prior publication and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. On behalf of all Co-Authors, the corresponding Author shall bear full responsibility for the submission. This research has not been submitted for publication nor has it been published in whole or in part elsewhere. We attest to the fact that all Authors listed on the title page have contributed significantly to the work, have read the manuscript, attest to the validity and legitimacy of the data and its interpretation, and agree to its submission to Journal of functional biomaterials.

References

- Bajkin BV, Vujkov BS, Milekic BR, Vuckovic BA. Risk factors for bleeding after oral surgery in patients who continued using oral anticoagulant therapy. JADA June 2015; 146(6): 375–381. [CrossRef]

- Pulicari, F, Pellegrini M, Scribante A, Kuhn E, Spadari F. Pathological Background and Clinical Procedures in Oral Surgery Haemostasis Disorders: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2076. [CrossRef]

- Dézsi BB, Koritsánszky L, Braunitzer G, et al. Prasugrel Versus Clopidogrel: A Comparative Examination of Local Bleeding After Dental Extraction in Patients Receiving Dual Antiplatelet Therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015 Oct;73(10):1894-900. [CrossRef]

- Costa V, Kaminagakura E. Anticoagulant-induced oral bleeding. Braz Dent Sci 2017 Jul/Sep;20(3): 158-60. [CrossRef]

- Jimson S, Amaldhas J, Jimson S et al. Assessment of bleeding during minor oral surgical procedures and extraction in patients on anticoagulant therapy. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015 Apr; 7(Suppl 1): S134–S137. [CrossRef]

- Zirk, M., Fienitz, T., Edel, R. et al. Prevention of post-operative bleeding in hemostatic compromised patients using native porcine collagen fleeces—retrospective study of a consecutive case series. Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016, 249–254 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Management of dental patients taking anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs. Dundee Dental education centre. Dundee. [Internet] 2015 August. Available from:http://www.sdcep.org.uk/published-guidance/anticoagulants-and-antiplatelets/.

- Bajkin BV, Bajkin IA, Petrovic BB. The effects of combined oral anticoagulant-aspirin therapy in patients undergoing tooth extractions: a prospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012 Jul;143(7):771-6. [CrossRef]

- Blinder D, Manor Y, Martinowitz U, et al. Dental extractions in patients maintained on continued oral anticoagulant: Comparison of local hemostatic modalities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:137–40. [CrossRef]

- Gröbe A, Fraederich M, Smeets R, Heiland M, Kluwe L et al. Postoperative bleeding risk for oral surgery under continued Clopidogrel antiplatelet therapy. Hindawi Pub Corp BioMed Research Int, V 2015, ID 823651, 4 pages. [CrossRef]

- Hanken H, Tieck F, Kluwe L, Smeets R, Heiland M et al. Lack of evidence for increased postoperative bleeding risk for dental osteotomy with continued aspirin therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015 Jan;119(1):17-9. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto Y, Niwa H, Minematsu K. Hemostatic management of tooth extractions in patients on oral antithrombotic therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008 Jan;66(1):51-7. [CrossRef]

- Zhu G, Wang Q, Lu S, Niu Y: Hydrogen Peroxide: A Potential Wound Therapeutic Target. Med Princ Pract 2017;26:301-30. [CrossRef]

- Schneeweiss S, Seeger JD, Landon J, Walker AM. Aprotinin during Coronary-Artery Bypass Grafting and Risk of Death. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:771-783. [CrossRef]

- Lyseng-Williamson KA. Aprotinin in adults at high risk of major blood loss during isolated CABG with cardiopulmonary bypass: a profile of its use in the EU. Drugs Ther Perspect 11 Nov 2019; 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Lee TJ1, Huang CC, Chang PH, Chang CJ, Chen YW. Hemostasis during functional endoscopic sinus surgery: The effect of local infiltration with adrenaline. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009 Feb;140(2):209-14. [CrossRef]

- Negrete OR, Molina M, Gutierrez-Aceves J. Preoperative administration of ethamsylate: reduces blood loss associated with percutaneous nephrolithotomy? A prospective randomized study. The J. of urology.2009; 181(4):625.

- Albiñana V, Giménez-Gallego G, García-Mato A, Palacios P, Recio-Poveda L et al. Topically Applied Etamsylate: A New Orphan Drug for HHT-Derived Epistaxis (Antiangiogenesis through FGF Pathway Inhibition). TH Open. 2019 Jul 26;3(3):e230-e243. [CrossRef]

- Levine M, Huang M, Henderson SO, Carmelli G, Thomas SH. Aminocaproic Acid and Tranexamic Acid Fail to Reverse Dabigatran-Induced Coagulopathy. Am J Ther. 2016 Nov/Dec;23(6):e1619-e1622. [CrossRef]

- Steinmetzer T, Pilgram O, Wenzel BM, Wiedemeyer SJA. Fibrinolysis Inhibitors: Potential Drugs for the Treatment and Prevention of Bleeding. J Med Chem. 2019 Nov 13. [CrossRef]

- Estcourt LJ, Desborough M, Brunskill SJ, Doree C, Hopewell S et al. Antifibrinolytics (lysine analogues) for the prevention of bleeding in people with haematological disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Mar 15; 3 :CD009733. [CrossRef]

- Halfpenny W, Fraser JS, Adlam DM. Comparison of 2 hemostatic agents for the prevention of postextraction hemorrhage in patients on anticoagulants. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001 Sep;92(3):257-9. [CrossRef]

- Mladenov DA, Tsvetkov TD, Vulchanov NL. Freeze drying of biomaterials for the medical practice. Cryobiology. 1993 Jun;30(3):335-48. [CrossRef]

- Speechley, JA. Dry socket secrets. Br Dent J 205, 168 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Lew WK, Weaver FA. Clinical use of topical thrombin as a surgical hemostat.Biologics : Targets & Therapy. 2008;2(4):593-599. [CrossRef]

- Lozano AC, Perez MGS, Esteve CG. Dental management in patients with hemostasis alteration. J Clin Exp Dent. 2011;3(2):120-6.

- Mankad PS, Codispoti M. The role of fibrin sealants in hemostasis. Am J Surg. 2001 Aug;182(2):21S-28S.

- René H, Fortelny RH, Petter-Puchner AH, Glaser KS, Redl H. Use of fibrin sealant (Tisseel/Tissucol) in hernia repair: a systematic review. Surg Endosc 2012; 26, 1803–1812. [CrossRef]

- Eberhard U, Broder M, Witzke G. Stability of Beriplast P fibrin sealant: storage and reconstitution. Int J Pharm. 2006 Apr 26;313(1-2):1-4. [CrossRef]

- Spotnitz WD. Fibrin Sealant: The Only Approved Hemostat, Sealant, and Adhesive-a Laboratory and Clinical Perspective. ISRN Surg. 2014 Mar 4;2014:203943. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mahmoudi A, Ghavimi MA, Maleki DS, Sharifi S, Sajjadi SS et al. Efficacy of a New Hemostatic Dental Sponge in Controlling Bleeding, Pain, and Dry Socket Following Mandibular Posterior Teeth Extraction-A Split-Mouth Randomized Double-Blind Clinical Trial. J Clin Med. 2023 Jul 10;12(14):4578. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martinowitz U, Mazar AL, Taicher S, et al. Dental extraction for patients on oral anticoagulant therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990 Sep;70(3):274-7. [CrossRef]

- Cardona-Tortajada F, Sainz-Gómez E, Figuerido-Garmendia J, et al. Dental extractions in patients on antiplatelet therapy. A study conducted by the Oral Health Department of the Navarre Health Service. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009 Nov 1;14 (11):588-92. [CrossRef]

- Carter G, Goss AN, Lloyd J, et al. Tranexamic Acid Mouthwash Versus Autologous Fibrin Glue in Patients Taking Warfarin Undergoing Dental Extractions: A Randomized Prospective Clinical Study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003 Dec;61(12):1432-5. [CrossRef]

- Perry DJ, Noakes TJC, Helliwell PS. Guidelines for the management of patients on oral anticoagulants requiring dental surgery. Brit Dent J Oct 13 2007; 203(7): 389–393. [CrossRef]

- Mamdouh Kamal Dawaud S, Hegab DS, Mohamed El Maghraby G, Ahmad El-Ashmawy A. Efficacy and Safety of Topical Tranexamic Acid Alone or in Combination with Either Fractional Carbon Dioxide Laser or Microneedling for the Treatment of Melasma. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2023 Jul 1;13(3):e2023195. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hupp JR, Ellis E, Tucker MR. Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery. 6th edition. Elsvier 2014; ISBN 978-0-323-09177-0. P 15-16: 183-185.

- Al-Mubarak S, Al-Ali N, Abou Rass M, et al. Evaluation of dental extractions, suturing and INR on postoperative bleeding of patients maintained on oral anticoagulant therapy. Br Dent J. 2007 Oct 13;203(7):E15. [CrossRef]

- Mani M, Ebenezer V, Balakrishnan R. Impact of Hemostatic Agents in Oral Surgery. Biomedical & Pharmacology Journal 2014; 7(1):215-219. [CrossRef]

- Roberts G. ABC of oral health. Dental emergencies. BMJ Sept 2000; 321(2):559-562. [CrossRef]

- Lillis T, Ziakas A, Koskinas K, et al. Safety of Dental Extractions During Uninterrupted Single or Dual Antiplatelet Treatment. Am J Cardiol. 2011 Oct 1;108(7):964-7. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, E.R., Taneja, M., Booth, R. et al. Antifibrinolytics in Cardiac Surgery: What Is the Best Practice in 2022. Curr Anesthesiol Rep 12, 501–507 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) 2015. Management of dental patients taking anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs. Dental Clinical Guidance. Available from: http://www.sdcep.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/SDCEP-Anticoagulants-Guidance.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Sarich TC, Seltzer JH, Berkowitz SD, Costin' J, Curnutte JT, Gibson CM et al. Novel oral anticoagulants and reversal agents: considerations for clinical development. Am Heart J. 2015;169(6):751–757.

- Umemura K, Iwaki T. The Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Prasugrel and Clopidogrel in Healthy Japanese Volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2016;5(6):480–487. [CrossRef]

- Faris A, Khalid L, Hashim M, Yaghi S, Magde T et al. Characteristics of Suture Materials Used in Oral Surgery: Systematic Review, International Dental Journal 2022; 72 (3): 278-287. [CrossRef]

- Hassan H K. Dental Suturing Materials and Techniques. 0010 Glob J Oto 2017; 12(2): 555833. [CrossRef]

- Szumita, R.P., Szumita, P.M. (2018). Local Techniques and Pharmacologic Agents for Management of Bleeding in Dentistry. In: Szumita, R., Szumita, P. (eds) Hemostasis in Dentistry. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).