Introduction

The advances in translational medicine and pharmaceuticals in the last three decades have given unprecedented tools to pediatric rheumatologists to achieve remission on treatment that is not in the expanse of high doses of steroids. It is now a common practice to personalize treatment by targeting specific key inflammatory mediators with the advent of biological response modifiers. Within this landscape, interleukin-1 (IL-1) is recognized as a primordial proinflammatory cytokine that is involved in pathogenesis of many autoimmune, autoinflammatory and immune dysregulatory diseases by promulgating a wide range of downstream cascade events [

1]. While IL-1a is constitutively expressed by many types of somatic as well hematopoietic cells, IL-1b is produced primarily by myeloid cells upon induction. To everyday practicing providers, there are two commercially available biologic response modifiers designed to antagonize IL-1 [

1,

2]: Anakinra is the recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1 RA), that competitively inhibits binding of IL-1a and IL-1b to its receptor and Canakinumab is the recombinant monoclonal antibody against IL-1b that prevents receptor-ligand interaction. Anakinra is FDA approved for severe rheumatoid arthritis for adults and for Neonatal Onset Multisystem Inflammatory Disease (NOMID) and Deficiency of IL-1 Receptor Antagonist (DIRA) and Canakinumab is FDA approved for adult and childhood Still’s disease, Cryoprotein-Associated Periodic Fever Syndromes (CAPS including NOMID), Tumor necrosis factor receptor associated periodic fever syndrome (TRAPS), hyper immunoglobulin D syndrome (HIDS), familial Mediterranean fever syndrome (FMF). Targeted treatment against IL-1 is safe and highly effective for these monogenic autoinflammatory conditions of children as summarized in a recent consensus report by the Pediatric Rheumatology community [

3]. Emergency FDA approval of Anakinra for treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 is further evidence of safety even for the control infection triggered inflammation [

4].

Anakinra is considered as an effective steroid sparing agent with unique advantages. Its short half-life (<24 hours) allows dose titration without concerns for long term adverse effects. While there is a paucity of efforts to expand indications for FDA approval, when available, its off-label use for a range of inflammatory and rheumatological diseases has been encouraging. So far there are several hundreds of patients in the literature confirming safety and efficacy of Anakinra for treatment of a variety of diagnoses, ranging from Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome of Children (MIS-C) and Kawasaki disease (KD) to polyarticular Juvenile Idiopathic arthritis (JIA), as summarized by Maniscalco V. et.al. [

5] and Tegtmeyer K, et.al [

6].

We here present our experience on anti-IL-1 agents in conjunction with the pattern of practice for treatment of children with an array of rheumatological conditions using these medications.

Methods

This is a single center and single provider based real-world evidence through retrospective chart review of patients followed by Division of Pediatric Rheumatology at Walter Reed National Military Medical center, Bethesda (WRNMMC). Access to medicine required approval through the pharmacy committee on case-by-case basis. As a part of our practice norm, families were involved as active participants of decision making in off-label treatment regimens following discussions on risks and benefits.

Results

Real World Experience on Anti-IL1 Biologic Response Modifiers

Over the last decade, we have treated 65 patients with anti-IL-1 biologic response modifiers. Our patient population did not include any children with NOMID, or DIRA, and treatment of 63 patients with Anakinra was based on off label applications when given as the first line biologic response modifier usually early in the disease course unless indicated otherwise. Canakinumab was used only for FDA approved indications in total of 9 patients as described below.

Patient Selection and Rational for Off Label Applications

In general, the factors of consideration prior to start Anakinra included likelihood of IL-1 mediated inflammation, age of the child, severity of symptoms, impact of disease on growth and development, access to care in case of infection, previous treatment regimens, and compliance to medications. All patients underwent screening for tuberculosis by blood (Quantiferon) or skin (PPD) testing. Baseline laboratories often included CBC, liver and kidney functions, quantitative immunoglobulins (IgG, M, A, E), inflammation markers, - i.e., Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR), C-Reactive Protein (CRP) and ferritin -, and if indicated, specific IgG titers (such as pneumococcal), T/B/NK flow cytometry, CH50 total complement, metabolic status (iron and vitamin D) and potential chronic illnesses (EBV, CMV). In addition, genetic studies, by Next Generation Sequencing at Keesler Air Force Base laboratories, was submitted to screen over 400 genes for mutations causing immune deficiency, immune-dysregulation, and inflammation.

Based on our experience, the rationale for off-label usage of Anakinra can be grouped under four main categories:

Treatment of new patients with signs and symptoms of high systemic inflammation who are undergoing diagnosis of exclusion. This is an important indication, as there is no single test for any of the rheumatologic illnesses and it may require time and close observation to reach conclusions. During the initial work-up use of steroids is not advisable while there is ongoing work-up for rule out infection or malignancy. Anakinra can provide a temporary measure to dampen inflammation when delay in treatment can cause poor outcomes.

Treatment of established patients presenting with unexpected escalation of inflammation possibly from perpetuating infection: Rheumatology patients are often treated with immunosuppressive medications and are prone to infection. When child presents with fever, increased inflammation markers (CRP, ESR), it can be difficult to tell if this is from disease flare or overlapping infection. There is a low threshold to start anti-microbials particularly if the patient appears toxic or in sepsis. While cultures are pending, if it becomes necessary to control inflammation, the available therapeutic options are limited. In these situations, IL-1Ra can be a relatively safe alternative to steroids to intervene inflammation.

The drug can be instrumental when there is a need to down regulate endothelial activation and vasculopathy expeditiously: This can be an important and challenging task particularly if intervention by steroids is of concern for potential adverse effects i.e., hypertension, hyperglycemia or hypercoagulation or very young age.

To utilize Anakinra as a “litmus test” to gain insights on immunopathogenesis and explore inflammatory pathways: This is particularly important for patients with poorly (or yet to be fully) defined rheumatological illnesses. when the literature is limited to design an optimal therapeutic regimen. In these cases, it is possible to control inflammation in a stepwise approach based on treatment response. In most cases, Treatment with this drug was often limited to brief time spans (1-4 weeks). For some patients with established diagnosis, intermittent applications on as needed basis was helpful as discussed below. If the child required long term anti-IL-1 treatment, Anakinra was often substituted with Canakinumab.

Observed Treatment Response to Anakinra

As a derivative to the rationale listed above, application of Anakinra was safe and effective in treatment of the following clinical presentations. Based on our gained experience, the emerging treatment protocols for the parameters of timing, dose and duration of its use are summarized in

Table 1.

1. Fever and Systemic Inflammation:

Anakinra was the 1st line treatment for patients with newly diagnosed systemic onset Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (sJIA), and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). It was also used as an adjunct treatment in children with KD upon partial response to intravenous immunoglobulin-G infusion (IVIG) or if the child presented with coronary artery involvement. It was also included in the initial treatment regimen of MIS-C and Acute Rheumatic Fever (ARF) with or without carditis.

Anakinra was used as a second line treatment for selected autoinflammatory diseases, i.e., periodic fever syndromes (PFS), following partial response to NSAIDs or colchicine. Immunopathogenesis of these involve common determinant of activation of IL-1 pathway. As a result, shared clinical markers, i.e., ESR, CRP and often ferritin. The CBC shows leukocytosis in children with sJIA, KD, MIS-C and some PFS, and leukopenia in MAS. Similar pattern is found for platelets (an acute phase reactant) except it can be high or low in MIS-C. At initial presentation, differentials may include sepsis and malignancy, limiting the use of steroids. It allows dose titration ranging from 1mg/kg/day to 20mg/kg/day. The response to Anakinra, as detailed below, was often robust and similar to those in the literature [

7,

8].

- a)

Autoinflammatory and immune dysregulatory diseases: a total of 12 patients (9 females) at a mean age of 7.4 years (median age of 7.6 years, ranging from 5 weeks to 20.3 years) with autoinflammatory conditions were treated with Anakinra. The indications included FMF (n=4), HIDS (n=3), TRAPS (n=2), PFAPA (n=1), ill-defined autoinflammatory syndrome (n=3). All FMF patients had single or compound heterozygous mutation(s) of MEFV gene. One of the FMF patients was a teenager female who also had Klippel Feil syndrome and type 1 diabetes mellitus improved on Anakinra 100mg twice daily for control of flares as well as blood glucose levels. Patients with TRAPS and HIDS had genetically confirmed diagnoses. One patient, 5 weeks of female with HIDS, was started on the drug as a first line medicine upon intensive care admission for possible Sweet syndrome. The remaining started on Anakinra after failed response to colchicine The usual dose of Colchicine was 0.3mg/day for toddlers, 0.6mg/day for older children that was titrated up by two-folds during flares. When this was inadequate to prevent flares, once daily injection of Anakinra was started. Initial dose of 1-3mg/kg/day was titrated up to 5mg/kg/day based on the treatment response. Patients with HIDS went onto start Canakinumab for injection site and/or quality of life due to prolonged need for daily Anakinra for disease control in 3 months. Two patients (two male siblings at ages 1.3 and 2.6 years of age) with TRAPS were progressed onto Canakinumab within a year of diagnosis that was discontinued for frequent infections. All FMF patients were heterozygous for MEFV mutation and well controlled on PRN Anakinra except for one (5 years old female) who later transitioned to Canakinumab at age 9 years for improved disease control. A 19-year-old female with heterozygous MEFV mutation manifesting with flares of low-grade fever, rash, capillary leak, and severe abdominal pain initially benefited from IL-1Ra along with IVIG that was transitioned to Adalimumab 7 years later upon establishing clinical diagnosis of Yao syndrome. The rest of patients were able to remain on the drug on as needed basis for flares, i.e., given once daily for 1 to 3 days PRN early signs of an upcoming flare, with or without continuing background treatment of colchicine. These patients experienced reduction in the number of flares within 6 months of starting the drug. In addition, a 4-year-old female with FMF started on Canakinumab directly without first using Anakinra for convenience upon parental military deployment and a 6-year-old male with established diagnosis of TRAPS continued his Canakinumab treatment that was started previously at a remote medical center as the first line treatment. Patients receiving Canakinumab remained in full remission.

- b)

Still’s disease and MAS: Six patients (4 females) at ages ranging from 5 to 22.8 years (mean of 12 years and median of 12.1 years of age) were diagnosed with systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis/Still’s disease (sJIA) and treated with Anakinra as an initial line treatment. At disease onset, 5 out of 6 patients had emerging elements of MAS with mild increase in LDH, ferritin and d-dimer. Three required inpatient-stay and 3 were co-treated with IV steroids. Out of those 6 patients, 13.1 years old female had pre-existing diagnosis of sickle cell disease (SSD) and pain crises. She and a 7-year-old male achieved remission off treatment after few months of being on the drug; Three patients followed a monophasic course and transitioned to Canakinumab. One patient (22.8-year-old female) had flares that overlapped with severe drug reaction to isoniazid or rifampin for dormant tuberculosis while on Anakinra; she reached remission after transition to Ruxolitinib for 18 months; four years into her diagnosis, she remained in remission off any treatment for over a year.

- c)

MIS-C, KD and ARF: Since first description of MIS-C in early 2020, Anakinra was reported to be efficacious to down regulate systemic inflammation caused by COVID-19 [

9]. The doses used was almost always over the upper limit of manufacturer’s recommended dose of 8mg/kg/day. We have experienced doses up to 10mg/kg/dose given intravenously twice a day without any observed adverse effects in patients with MIS-C who had negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR. Four patients with MIS-C (2 females) at mean age of 9.9 years (range 1.5 to 15 years), were treated with Anakinra along with IV methylprednisolone (10-20mg/kg/day divided q6-8 hours), IVIG (2g /kg/dose), aspirin (30mg/kg/day divided q8hr) and Enoxaparin. All had cardiovascular involvement with increased cardiac enzymes; both males (at 11.5 and 13.0 years of age) also had coronary artery aneurism (CAA). Anakinra dose was titrated down to 2 to 5 mg/kg/day after normalized cardiac enzymes followed by slow wean over the next 2 weeks. The treatment course was monophasic and allowed coming off treatment in 4 to 8 weeks as summarized before [

10]. Echocardiogram (ECHO) at one year follow-up showed either normalized (initial z score +5.8) or markedly improved (z score down from +6.0 to +2.8) readings on coronary arteries.

We have treated four patients (2 females) with KD or atypical KD at mean age of 4.2 years (range 1.5 to 10.9 years) with this drug. This was on standard background treatment with IVIG and high dose aspirin for up to 10 days. Two patients received it early in the course for the concern of emerging MAS or presence of pan-carditis. The other two had mild coronary artery dilatation and were spiking fever even after two rounds of IVIG (2g/kg/dose). All patients recovered fully and showed normalized ECHO at 2 weeks follow-up. This is similar to published reports on treatment resistant KD [

11]

Three patients (2 females) with diagnosis of ARF were treated with Anakinra upon fulfilling Jones criteria and evidence of past exposure to Group A beta hemolytic Streptococcal infection (GABHS). Two of the three (about 34 month and 16.6 years of age) had carditis, and one (about 7 years of age) had migratory arthritis as the major criteria. The teen did not have fever but presented severe mitral regurgitation (MR) and aortic insufficiency. The toddler was initially treated with two rounds of IVIG and aspirin for incomplete KD. Upon evidence of partial response with return of fever, she was started on Anakinra by Rheumatology. The other two, received the drug as the first line treatment. All three patients improved clinically and for laboratory results for ESR and CRP within 5 to 10 days of treatment. ECHO findings normalized for the toddler. The teen showed significantly improved ECHO findings for MR that was down to moderate levels; he was not a good candidate for steroids for obscure efficacy of steroids on MR per literature and for his weight being 95% for age. After he was treated with Anakinra 100mg BID x3 days then once daily for a week, his laboratories showed ESR normalized from 55 to 20 mm/hr (normal <28) and B-natriuretic peptide (BNP) from 1,163 to 36 ng/ml (normal <125). All three patients tolerated weaning off the drug in 7 to 14 days and remained stable. To our knowledge treatment of ARF with Anakinra is a novel approach.

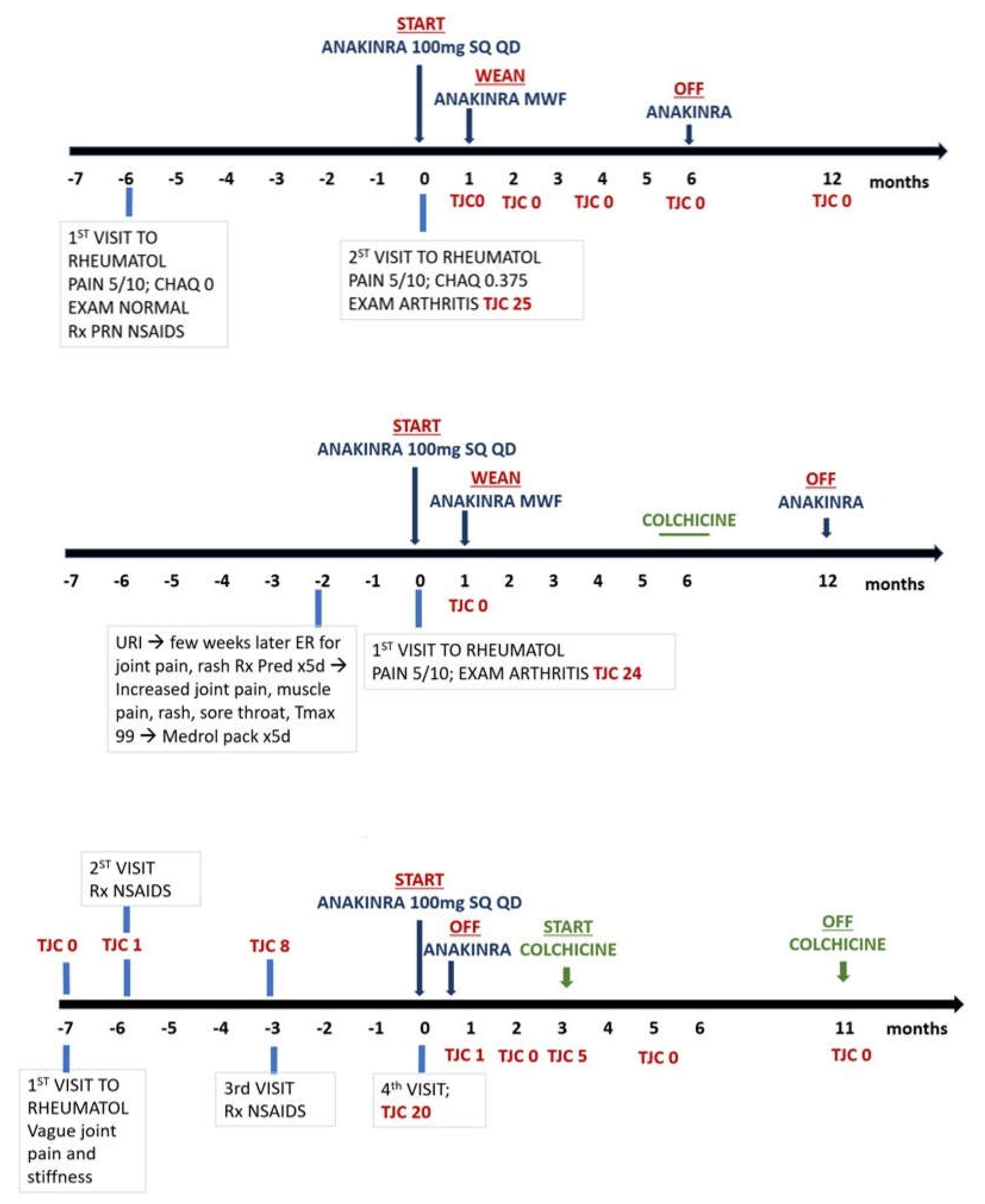

2. Post viral arthritis: Nine female patients at a mean age of 14.1years (range 10.1 to 19 years) with new onset arthritis following recent EBV infection were treated with IL-1Ra as the first line of immunomodulatory treatment. The diagnosis was based on increased blood EBV antibody titers; one patient also had positive EBV PCR. These patients had failed to improve on NSAIDs provided by the primary care providers. The rational for using Anakinra was for the ambiguity of infectious versus post infectious synovitis and trying a short acting targeted treatment before commitment for long term treatment with conventional DMARD, i.e., methotrexate or anti-TNF biological response modifiers. Furthermore, one patient had a history of positive Quantiferon required isoniazid (INH) treatment. All patients presented with fatigue, joint pain, morning stiffness (range 30minutes to all day); two patients also had low grade fever (<100F) along with transient erythematous non-itchy rash. All had had TJC of >14 affecting mostly hands, wrists, elbows, ankles, and knees. The mean time between onset symptoms and start of treatment varied between 1 to 6 months.

Figure 1 summarize treatment response over time. Similarly, one patient with post-strep chronic reactive arthritis affecting multiple joints responded well to <1week treatment with the drug. Per chart review, patient transitioned back to Naprosyn PRN and remained well without further need of rheumatology follow-up. In comparison, to our knowledge, treatment of post-EBV or post Strep arthropathy with Anakinra is a novel approach.

On the other hand, Anakinra was marginally effective on patients with established dx of juvenile Idiopathic arthritis of two female patients at ages of about 6 and 12 years who were partially responsive to anti-TNF treatment. Similar observation on limited efficacy of Anakinra for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [

12]. A 17.6-year-old male with new onset rheumatoid factor (RF) positive, rheumatoid arthritis also did not respond to initial treatment with this drug prior to commitment to anti-TNF medication. The latter two patients (12-years old female- and 17.6-years old male) had positive EBV antibodies.

3. Mucositis and serositis: Patients with limited mouth ulcers, such as those seen with PFAPA, were usually first treated with colchicine prior to considering Anakinra. Two patients at ages of 12.8 and 17 years with severe mucositis from incomplete Behcet’s syndrome causing recurrent mouth ulcers and genital ulcers (without uveitis or systemic concerns for fever, joint pain, or signs of systemic vasculitis) responded well to intermittent applications of this drug given 3 to 7 days upon early signs of emerging new ulcers. Similarly, a 16year-old male with diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-Induced Rash and Mucositis (MIMS) responded well to Anakinra that was provided on as needed basis for up to 7 days during two flares 3 years apart. Likewise, two female patients at ages of about 17 and 23 years followed by our clinic for subtle recurrent pericarditis, resistant to colchicine, manifesting with pain also responded well to intermittent brief application of Anakinra for few daily doses at a time that resulted with gradual dissipation of flares within 6 months. Our results were similar, if not better, to the published report on efficacy of Anakinra on oral ulcers [

13].

4. Systemic autoimmune diseases: A total of 13 patients, 11 females, at mean age of 14.3 years (Median 15.5 years, range 9 to 21.5 years) with systemic connective tissue disease (CTD), eight patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, three with undifferentiated CTD, and two with Sjogren’s disease were treated with daily Anakinra. The indication included pericarditis (2 lupus), pleural effusion (1 lupus), polyarticular arthritis (3 lupus, 4 CTD and 1 Sjogren’s), and MAS (2 lupus). The drug was given 100mg once or twice a day for serositis or MAS during inpatient stay (n=5). The rest of the patient received it on an outpatient basis 100mg once a day for arthritis for 1-2 weeks while continuing background treatment as a steroid sparing agent. This allowed clinical stability, but the disease control required further tailoring treatment with other disease modifying antirheumatic drugs. One patient with Sjogren’s syndrome and chronic leukocytoclastic vasculitis over the lower extremities remained dependent on the IL-1Ra to remain in clinical remission on treatment. Our observations were similar to published reports on treatment of lupus patients with Anakinra for fever or arthritis [

14,

15].

5. Small vessel vasculitis: Two male patients at ages of about 7 and 10 years with HSP and a 13.5-year-old female with alveolar hemorrhage due to ANCA associated vasculitis (AAV) was treated with daily Anakinra. Patients with HSP had target organ involvement of skin and GI track with palpable purpura and colicky abdominal pain. Both patients showed robust response to daily dose over a week treatment. For the patient with AAV, it was used briefly as an adjunct agent while receiving steroids, immunosuppressives and B-cell depleting biologic response modifiers; she was able to recover from progressive hypoxia without ventilator support.

Discussion

Diagnosis, and assessment of rheumatological diseases can be challenging particularly when there is limited access to subspecialty. These children may present with life threatening inflammatory storm as seen in MIS-C, KD, MAS, ARF, vasculitis and sJIA. Even when inflammation is limited to a target tissue as seen in serositis, mucositis, or post viral arthritis, there is often suffering from pain and discomfort. Currently, there are only two first line treatment options, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroids. NSAIDs are weak immunomodulators and often used as anti-pyrectics by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis. Steroids can modulate many components of the innate and specific immune system; however, the adverse effects can be detrimental. It is, therefore, imperative to have treatment options that are safe and effective to down regulate inflammation. Based on our real-world observations, Anakinra is a good candidate to fulfill this gap as a steroid sparing agent.

Diseases cared by rheumatology can be stratified in 3 main categories [

16]: autoinflammatory (that are monogenic diseases, some of which are due to mutations in the IL-1 pathway), acute inflammatory diseases (that includes reactive conditions such as KD, MIS-C, ARF, reactive arthritis etc.) and autoimmune diseases hallmarked with presence of adversary immune memory (such as lupus, myositis, scleroderma, vasculitis etc.). The IL-1Ra was quite effective particularly for autoinflammatory and acute inflammatory conditions that are known to derived from innate immunity. It can be used as a single drug or as a part of combination treatment tailored for the patient. To our experience, treatment confined to brief durations was usually sufficient to resolve or reduce the acute inflammation. In cases with systemic autoimmune diseases, the drug provided clinical stabilization to some extent that allowed time for proper diagnosis and/or tailoring long time treatment. Anti-IL-1 treatment was initiated when immunopathogenesis of a given condition is known to- or likely to- involve innate immunity; At times, trial and error approach can be justified due to its short half-life while titrating the dose carefully based on the severity of inflammation, response to treatment and onboard risk for infection. The guiding principle for these decisions is often based on pattern recognition and basic laboratory investigations. In accord, we stratified the clinical indications and the underlying rationale for using anti-IL-1 medications in 4 domains. Furthermore, in our hands, most cases required Anakinra for brief periods of time (

Table 1). So far, the recombinant IL-1Ra drug and other biological response modifiers are FDA approved for the assumption of continuing use; our data suggests ‘as-needed’ application closely tailored to patient’s unique needs is a viable option. Treatment outcomes were similar to published experience and further encouraging for novel observations on post-viral arthritis, post Strep chronic reactive arthritis, MIMS and ARF.

Based on the retrospective review following the guidance by the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0, anti-IL-1 biologic response modifiers were tolerated well. There was no significant increase in infection. As reported before [

17], injection site reaction was the most common (15% of cases) adverse effect for Anakinra that required weaning (to every other day) or discontinuation of injections. It was often given as intravenous route during hospital stay that was tolerated well even at high doses.

Each brand of commercially available anti-IL-1 biological response modifier in the market, offers different set of benefits based on its chemical and biologic properties. The preference of using one over the other is determined mostly by its half-life, availability, and cost. For instance, Canakinumab was used for patients who are proven to benefit from blockage of IL-1 pathway. It is a preferred formulation for prolonged half-life of 4 weeks for treatment of children who need long term treatment. However, Canakinumab is not preferred for patients with possible infection or unclear diagnosis. Although the cost of a month supply of Canakinumab is almost 10 times higher than that of Anakinra, it is an excellent maintenance treatment for broader range of FDA approved indications and requiring minimal number of injections a year. To our experience, sequential application of Anakinra and Canakinumab has been the safest and most cost-efficient approach.

Access to biologic response modifiers is challenging due to restrictions set forward by the health insurance industry in compliance to FDA guidance. In general, the pediatric indications of Anakinra are limited to NOMID and DIRA patients that totals for less than 100 reported cases in the literature [

18]. Even for polyarticular arthritis, the formulation is FDA approved only for individuals

>18 years. Off label application is becoming very difficult even within the military system although rapid recovery of the child is essential for parent’s full commitment to military readiness. It is important to emphasize that neither Anakinra nor Canakinumab is a new drug, and both have high post marketed safety profile [

17]. Furthermore, the scientific knowledge accumulated over the last 5 decades through clinical and preclinical studies justify the primordial importance of IL-1 in many inflammatory conditions. Based on the shared vision among the rheumatology community, “targeted interventions” are needed for treatment of a growing child, as the adverse effects of steroids are inevitable and constitute a great concern as summarized in the recent commentary by M Romano, et.al. [

19] overcoming the obstacles within the current landscape to help these children requires fundamental transformation within the health system. Accordingly, it is essential to emerge a patient centered and industry friendly new format to expand FDA approved indications for inflammatory diseases. Toward this vision, it is essential to bring awareness among the primary care providers and foster grassroot discussions blended with parent/patient voice and advocacy as the backbone of efforts for betterment of care to our patients.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda (protocol code #413526 and EDO-2020-0493; date of approval November 2015 and May 2020, respectively).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to protocol design of retrospective chart review without personal identifiers.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses sincere appreciations to the families and non-profit organizations for children with rare diseases. The author also extends thanks to Dr. Deborah McCurdy for the critical review of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no role of any commercial entity in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Dinarello, C.A. Overview of the interleukin-1 family of ligands and receptors. Semin Immunol. 2013 Dec 15;25(6):389-93. Epub 2013 Nov 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinarello, C.A.; van der Meer, J.W. Treating inflammation by blocking interleukin-1 in humans. Semin Immunol. 2013 Dec 15;25(6):469-84. Epub 2013 Nov 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Romano, M.; Arici, Z.S.; Piskin, D.; Alehashemi, S.; Aletaha, D.; Barron, K.S.; Benseler, S.; Berard, R.; Broderick, L.; Dedeoglu, F.; Diebold, M.; Durrant, K.L.; Ferguson, P.; Foell, D.; Hausmann, J.; Jones, O.Y.; Kastner, D.L.; Lachmann, H.J.; Laxer, R.M.; Rivera, D.; Ruperto, N.; Simon, A.; Twilt, M.; Frenkel, J.; Hoffman, H.; de Jesus, A.A.; Kuemmerle-Deschner, J.B.; Ozen, S.; Gattorno, M.; Goldbach-Mansky, R.; Demirkaya, E. The 2021 EULAR/American College of Rheumatology points to consider for diagnosis, management and monitoring of the interleukin-1 mediated autoinflammatory diseases: cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes, tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome, mevalonate kinase deficiency, and deficiency of the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022 Jul;81(7):907-921. Epub 2022 May 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huet, T.; Beaussier, H.; Voisin, O.; Jouveshomme, S.; Dauriat, G.; Lazareth, I.; Sacco, E.; Naccache, J.M.; Bézie, Y.; Laplanche, S.; Le Berre, A.; Le Pavec, J.; Salmeron, S.; Emmerich, J.; Mourad, J.J.; Chatellier, G.; Hayem, G. Anakinra for severe forms of COVID-19: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020 Jul;2(7):e393-e400. Epub 2020 May 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maniscalco, V.; Abu-Rumeileh, S.; Mastrolia, M.V.; Marrani, E.; Maccora, I.; Pagnini, I.; Simonini, G. The off-label use of anakinra in pediatric systemic autoinflammatory diseases. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020 Oct 16;12:1759720X20959575. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tegtmeyer, K.; Atassi, G.; Zhao, J.; Maloney, N.J.; Lio, P.A. Off-Label studies on anakinra in dermatology: a review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 Feb;33(1):73-86. Epub 2020 Apr 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.C.; May, J.W.; Cunningham, M.W.; Jones, O.Y. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C), a Post-viral Myocarditis and Systemic Vasculitis- A Critical Review of Its Pathogenesis and Treatment. Front Pediatr. 2020 Dec 16;8:626182. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cron, R.Q. Biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs to treat multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2022 Sep 1;34(5):274-279. Epub 2022 Jul 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirks, B.T.; Geracht, J.C.; Jones, O.Y.; May, J.W.; Mikita, C.P.; Rajnik, M.; Helfrich, A.M. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Report on Managing the Hyperinflammation, Military Medicine, , usaa508. c. [CrossRef]

- Loncharich, M.; Klusewitz, S.; Jones, O. Post-COVID-19 Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children and Adults: What Happens After Discharge? Cureus. 2022 Apr 24;14(4):e24438. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Giovanna Ferrara· Teresa Giani · Maria Costanza Caparello, Carla Farella, Lisa Gamalero, Rolando Cimaz. Anakinra for Treatment-Resistant Kawasaki Disease: Evidence from a Literature Review. Pediatric Drugs (2020) 22:645–652. [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.; Jobanputra, P.; Barton, P.; et al. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of anakinra for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in adults: a systematic review and economic analysis. 2004. In: NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme: Executive Summaries. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2003-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62266/.

- Grayson, P.C.; Yazici, Y.; Merideth, M.; Sen, H.N.; Davis, M.; Novakovich, E.; Joyal, E.; Goldbach-Mansky, R.; Sibley, C.H. Treatment of mucocutaneous manifestations in Behçet's disease with anakinra: a pilot open-label study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017 Mar 24;19(1):69. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dein, E.; Ingolia, A.; Connolly, C.; Manno, R.; Timlin, H. Anakinra for Recurrent Fevers in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Cureus. 2018 Dec 27;10(12):e3782. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ostendorf, B.; Iking-Konert, C.; Kurz, K.; et al. Preliminary results of safety and efficacy of the interleukin 1 receptor antagonist anakinra in patients with severe lupus arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2005;64:630-633.

- Jones, O.Y.; McCurdy, D. Cell Based Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases in Children. Front Pediatr. 2022 May 9;10:855260. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arnold, D.D.; Yalamanoglu, A.; Boyman, O. Systematic Review of Safety and Efficacy of IL-1-Targeted Biologics in Treating Immune-Mediated Disorders. Front Immunol. 2022 Jul 6;13:888392. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jesus, A.A.; Goldbach-Mansky, R. IL-1 blockade in autoinflammatory syndromes. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:223-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zitoun, N.M.; Demirkaya, E.; Goldbach-Mansky, R.; Romano, M. Time for a new approach to drug development for rare systemic autoinflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2024 Jun;20(6):317-318. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).