1. Introduction

More than 70% of European citizens live in smaller or larger conurbations. As a consequence, according to WHO estimates [

1,

2] the urban population in EU Member States is exposed to the harmful effects of air pollutants, mainly the fine particulate matter, PM

2.5, driven by energy use and road transport (affecting 97% of the population) and the nitrogen oxides, NO

X, due predominantly to emissions from road transport (affecting 94% of the population). According to [

3], despite the visible improvements in EU cities’ air quality over the last decade, achieving safe, in terms of health impacts, levels of key pollutants require further emission reduction. Exposures to these dominating pollutants create serious health risks [

1,

4]. At the same time, in most cases [

5,

6,

7] they exceed the official concentration limit values, particularly the recommended and much more restrictive World Health Organization guidelines [

1,

4,

5]. In particular, 307,000 premature deaths in the EU in 2019 resulted from exposure to fine particulate matter. Under the European Green Deal’s Plan, the European Commission set the

2030 goal of reducing the number of premature deaths caused by PM

2.5 by at least 55% compared with 2005 levels.

In most European cities [

4,

5,

6], the residential sector is indicated as the dominant source of PM

2.5 emissions (often above 50% share), with smaller contributions from transport (around 15%) and other sectors [

6]. Municipal sector emissions are primarily anthropogenic, consisting of the primary PM

2.5 and also including a condensation fraction. Moreover, this primary PM

2.5 fraction is the precursor with the highest share in most cities (72%), responsible for the high total PM

2.5 concentrations [

6]. Many studies also emphasize that the negative health effects associated with the heating systems operating in the residential sector are induced by outdoor and indoor pollutants [

8,

9,

10]. These results suggest that this sector should be key in any policy target to improve air quality. Hence, in the climate and fuel policies dealing with the residential sector, coal and other carbon-based solid fuels should be first eliminated, and then biomass, even though biomass is often treated as a climate-neutral fuel [

6].

Urban transport is the dominating sector causing NO

x emission (about 50%), with a minor contribution (about 15%) from residential heating [

7]. Nitrogen oxides NO

x, along with particulate matter concentrations, are another key pollutants affecting the urban environment, posing a serious threat to the health of residents [

3]. Moreover, they play a critical role in determining tropospheric ozone concentrations. To mitigate the harmful effects of these transportation pollutants, Low-Emission Zones (LEZ) are recently in operation in more than 320 European cities, and more are being launched at present [

7]. Hence any strategy aiming to achieve climate neutrality for the city should consider both of the above pollutants.

According to the data collected from air quality monitoring by the Polish institutions, outdated heating stoves are mostly responsible for particulate matter emissions, PM

10 and PM

2.5. They mainly contribute to frequent smog episodes. As stated by the National Center for Balancing and Emission Management (KOBIZE) [

11], the main sources of fine particulate emissions to the atmosphere in Poland are solid fuel combustion processes in the residential sector connected with building heating. Emitters there are located in inhabited areas, and the emissions usually happen at a low height above ground level (so-called “low emission”). As a result, these emissions directly shape the concentrations of pollutants in residential areas and finally determine the exceeds of air quality standards both for PM

2.5 and PM

10 particulate matter. In contradistinction to Western European cities, where biomass is the dominating fuel used in this sector [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], the residential sector heating in Poland is still based on hard coal and lignite combustion [

12]. This causes a much more harmful impact on the environment and the population’s health. In Poland in 2018, emissions from the residential sector accounted for about 44% of total PM

10 emissions and 52% of total PM

2.5 emissions [

7].

Road transport is the second category of emission sources that significantly impacts PM concentrations. Emissions of this sector also occur at low altitudes and considerably influence concentrations of harmful pollution that are particularly dangerous in urban areas. Road transport, however, is at the same time a major source (about 50% contribution) of nitrogen oxides emissions, NO

x. High concentrations of nitrogen oxides in densely populated urban areas are also responsible for negative health effects [

2,

4,

5].

Moreover, the final urban air quality in Poland is significantly affected by the influx of pollutants from external sources, particularly from the commercial energy sector, which is still based on coal combustion. In 2017 and 2018, hard coal and lignite accounted for 83% of the total fuel demand in this sector [

12,

13]. In 2024, this share drops to around 63% (43,4% hard coal and 19,6% lignite) [

13], which still is a high contribution. The impact of commercial power generation on pollution levels in urban conurbations is evident when looking at a significant share of external influxes of pollutants, particularly PM

2.5 and NO

x whenever any urban area is considered.

2. Methodology. Air Quality Improvement Programs

Launched in September 2018, the Polish government’s Clean Air priority program covers the period (2018-2029). Its primary goal is to reduce atmospheric emissions of harmful substances generated by heating single-family homes, which mostly utilize poor-quality fuel in outdated domestic stoves. Also, the program’s purpose is to improve energy efficiency and reduce emissions of particulate matter and other air pollutants from existing buildings. Moreover, the program aims to eliminate such emissions from newly constructed buildings in the residential sector.

For existing detached residential houses, the program finances, among other things, the replacement of old-generation coal-fired heat sources with district heating systems, electric heating, condensing gas boilers, heat pumps, or new-generation solid fuel (coal or biomass) boilers. In addition, the project scope includes the buildings’ insulation and the use of renewable sources of heat and electricity. In newly constructed residential buildings, low-emission installations will be subsidized.

As a result of the Clean Air program’s [

14] nationwide operation over the years 2018-2023 until now [

15], a total of 666,103 new heat sources have been installed, including 34.2% of heat pumps, 35.7% of gas condensate pumps, 19.6% of biomass boilers, 8.7% of coal boilers, and 1.5% of electric heating. As a result of this modernization, the share of fossil fuels and firewood significantly decreased. Then, the share of low-emission installations in the residential sector, especially heat pumps, increased noticeably. According to estimates in [

15], a clear difference in the share of the main energy carriers in residential households exists (

Table 1).

The problem of the municipal sector being the main source of air pollution in urbanized areas highly affects conurbations of any size [

6,

8]. For example around 15,000 outdated and non-ecological stoves operating in Warsaw’s municipal sector in 2017 were responsible for frequent smog episodes and exceedances of the permissible level of PMs concentrations at all monitoring stations operating in the city. The same heating sources were also causing constant exceedances of the limit level of the carcinogenic benzo[a]pyrene throughout the city. In general, poor air quality causes, among other things, respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, exacerbation of asthma, as well as concentration problems and depression. As shown in [

16], for this reason around 6,000 people died prematurely each year in Mazovian Voivodeship. Thus, reducing levels of harmful air pollution was one of the main goals set by the city authorities.

According to the Mazovian Anti-smog Resolution [

17], operating under the nationwide Clean Air Program, additional radical actions have been taken to eliminate the most harmful sources of air pollution in Warsaw. The Resolution launched in 2017 applies to all users of devices with a power of up to 1 MW that use coal, solid fuels produced using coal or biomass. As part of this program, residents can also count on additional funding. Following the accepted premises, after Nov.11.2017 only boilers that meet Ecodesign requirements [

18,

19] can be installed. The obsolete coal/wood stoves that do not meet the respective quality standards should have be removed by the end of 2022. Moreover, the version amended in 2022 [

19,

20,

21] forbids the use of coal and solid fuels produced using coal: (a) from 1 October 2023, within the administrative boundaries of the City of Warsaw, and (b) from 1 January 2028, within the administrative boundaries of 39 municipalities in close vicinity of the city.

As a result of the Clean Air Program and the Mazovian Anti-smog Resolution to date operation, air quality in Warsaw has improved noticeably. The initial number of about 15,000 obsolete coal-burning stoves, operating in the city in 2017, was reduced by above 80% [

22]. The reduction and modernization of heat sources include both municipal and private sources. As a result of the comprehensive modernization, the use of heat pumps and photovoltaic energy has increased significantly. In addition, some existing buildings in the residential sector have been connected to the district heating network.

The above city’s efforts to improve air quality – primarily the removal of most fossil fuels – have reduced pollution levels in recent years. For example, the permissible level of annual average PM

2.5 concentrations (20 μg/m

3) in 2018 was previously exceeded at all stations, while last year most results were within the norm. In turn, the annual mean particulate matter concentrations from 2018 to 2023 decreased by about 25-30%, for both PM

10 and PM

2.5 pollutants [

22].

However, in the fight to improve air quality, the city authorities do not focus only on fossil fuels used in residential districts, as urban transport is the second principal source of air pollution in the city. The main pollutants in this case are nitrogen oxides, NO

x. Car traffic is responsible for more than 50% of the total concentration, although cars also contribute (about 13-15%) to the total particulate matter pollution. It is estimated that the city’s pro-ecological activities and the natural process of car fleet modernization between 2018 and 2023 resulted in a decrease in NO

x emissions from this sector by about 11.5%. This estimate is based on a comparison of the records of the annual average concentration at the main Warsaw’s traffic station versus the averaged value for the three urban background stations, for 2018 and 2023, respectively [

23].

To reduce emissions from the most poisonous vehicles, the authorities also introduce a Low-Emission Zone (LEZ). The aim is to reduce the negative impact of traffic-induced pollution on an urban area environment, where car emissions are strictly regulated to meet certain environmental criteria. Such solutions have gained popularity, especially in Western European agglomerations operating more than 300 zones nowadays, mainly in Italy and Germany [

7,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. On the other hand, there are no zones in operation to date in Eastern and Central European countries, and Warsaw is the first city in this region where such a zone is being created.

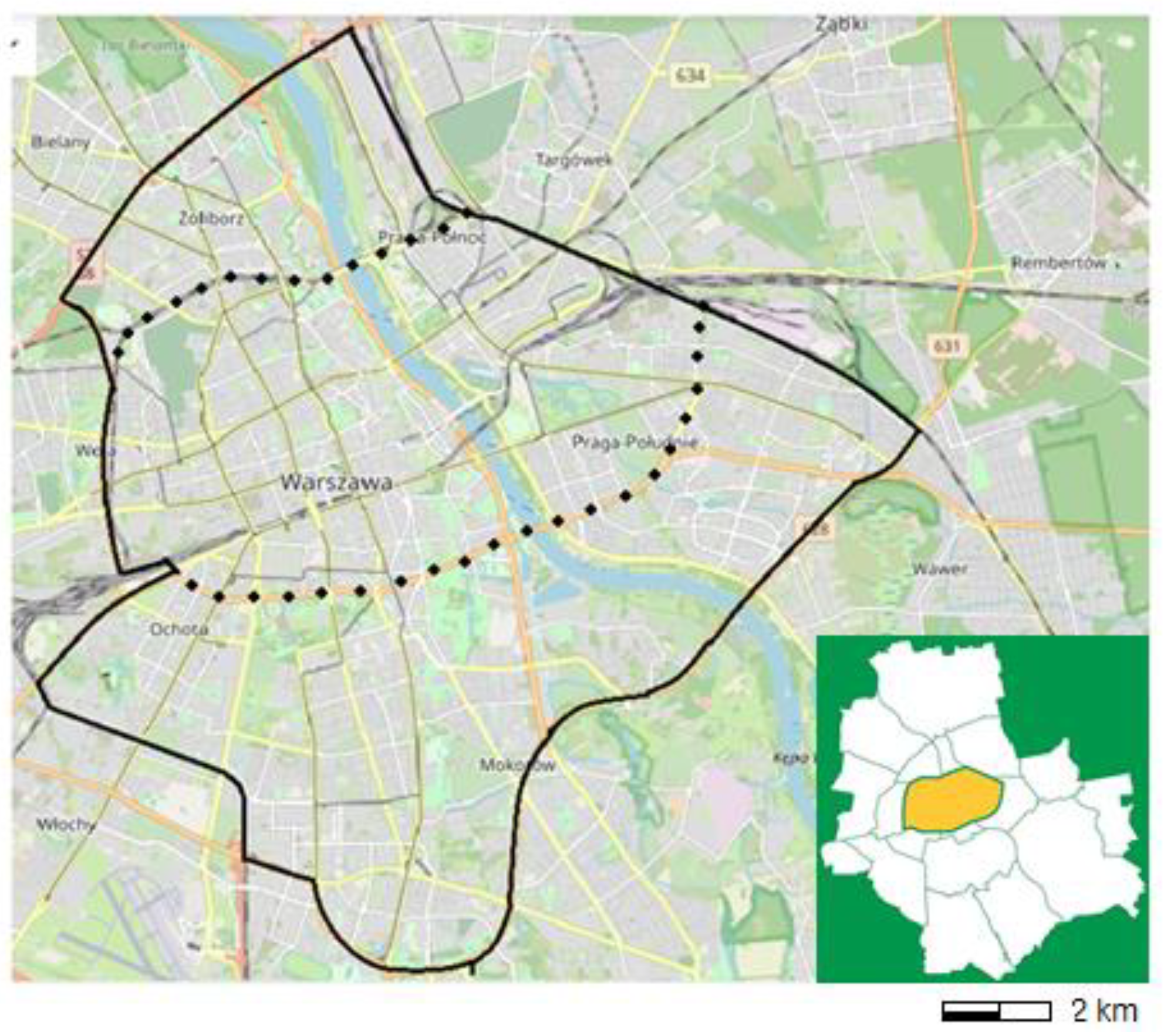

The zone will take effect from 1 July 2024 and the full implementation process is divided into five two-year stages, in which the zone admission criteria are progressively tightened (compare

Figure S1). The project draws on the results of a Warsaw’s street emissivity study carried out in autumn 2020 under the supervision of the ICCT experts [

7,

29,

30]. A study shows that most pollution comes from older, especially diesel cars. Measurements of about 150,000 vehicles revealed that cars manufactured before 2006, though accounted for only 17% of the fleet, were responsible for 37% of nitrogen oxide (NO

x) emissions and 52% of particulate matter (PM) emissions caused by transport. Using data from this test, it is possible to estimate, [

7,

29,

30], the expected reduction in emissions of both pollutants associated with the implementation of subsequent LEZ stages (see

Table S1). The results are used in the next section in simulation studies of environmental effects when some specific LEZ variants are introduced.

In January 2023, the Warsaw authorities presented the initial draft of the Low-Emission Zone, and at the same time, they launched public consultations. The objective of the 2023 consultation was primarily to define the boundaries of the projected zone [

31]. Having analyzed all opinions collected and expert reports, the authorities decided to increase the area of the zone [

32]. As a result, two alternative versions of the Low-Emission Zone for Warsaw, shown in [

7,

31,

32], were presented for final decision: (a) the basic version, in which the zone covers around 7-8% of the city’s area, and (b) an extended version, more than twice as wide, covering around 18% of the city’s area. The expanded version can make the zone more effective in improving air quality, but at the same time, it means some additional difficulties for drivers. Finally, during the Warsaw Council meeting in December 2024, a base (smaller) version of the zone was approved for implementation, with the possibility of future implementation of the extended version.

4. Summary and Discussion

Despite apparent improvements in the city’s air quality in recent years, there are still opportunities for further progress. The Anti-smog Resolution, modified in 2022 [

20], introduces a ban on hard coal and other using it solid fuels: (a) from 1.10.2023 within the administrative boundaries of Warsaw and (b) from 1.01.2028 within the boundaries of the municipalities directly surrounding the city. At the same time, starting in 2024, Warsaw became the first city in Central Europe to join the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty [

37], an initiative designed to complement and support the implementation of the Paris Agreement [

38]. By supporting the Treaty, Warsaw has joined 70 other cities, including London, Paris, Brussels, Calcutta, and Los Angeles, that have pledged to push for the end of the fossil fuel era. The measures concerning the surroundings are also important given the continuing strong impact of those municipalities on air quality in the city itself. Thus, appropriate pro-environmental measures taken at the local level are of great value in this case.

In particular, it is shown in [

37] that the residential sectors in Warsaw’s close vicinity are responsible, on average, for about 19% of the total PM

2.5 concentration. However, since the modernization of heat sources in this area has not spread out over the years 2018-2029, the emissivity of the housing sector there is currently much higher than in the city itself. As shown in [

35], as a result of past efforts, the share of obsolete and off-grade household furnaces to the total number of individual households in the city fell to about 6%. On the other hand, this share is much higher in the municipalities immediately surrounding the city, sometimes reaching almost 50% [

37]. Continued consistent modernization of this sector in the city’s surroundings should also help to improve air quality in the city itself in the coming years, especially concerning particulate pollution.

A significant factor of the total air pollution concentration in the city is the transboundary influx, including both primary and secondary components, with the related sources located outside of the discussed urban area. One reason of this is, that fossil fuels in Poland still account for about 65% of the total energy supply, with hard coal and lignite representing a major share. At the same time, due to the central government’s misguided policy, the shift away from coal has been slowed considerably over the past eight years by restricting the development of renewable energy sources, and particularly by drastically limiting the construction of energy windmills. According to the modernized Windmill Law currently being drafted [

40], from January 2025, the minimum required distance from a residential building to a windmill under construction is to be 500 m (previously 1000 m, then reduced to 700 m), which should significantly expand the possibilities of using these renewable energy sources. In the longer term, a significant improvement should be achieved by replacing coal with nuclear power plants.

In the case of road traffic pollution, zone expansions should be analyzed in the long term, which, as shown above, can indicate improvements, especially when nitrogen oxide pollution is considered. Further improvement in this area will occur after implementing the new Euro 7 emission standard in 2026, regardless of permanent fleet replacement/modernization. Moreover, the share of hybrid cars in newly registered vehicles in Poland is growing, with more hybrids registered in the last year than internal combustion-powered ones. That is a favorable situation from the point of view of air quality protection, especially in cities where the use of battery drives is predominant.

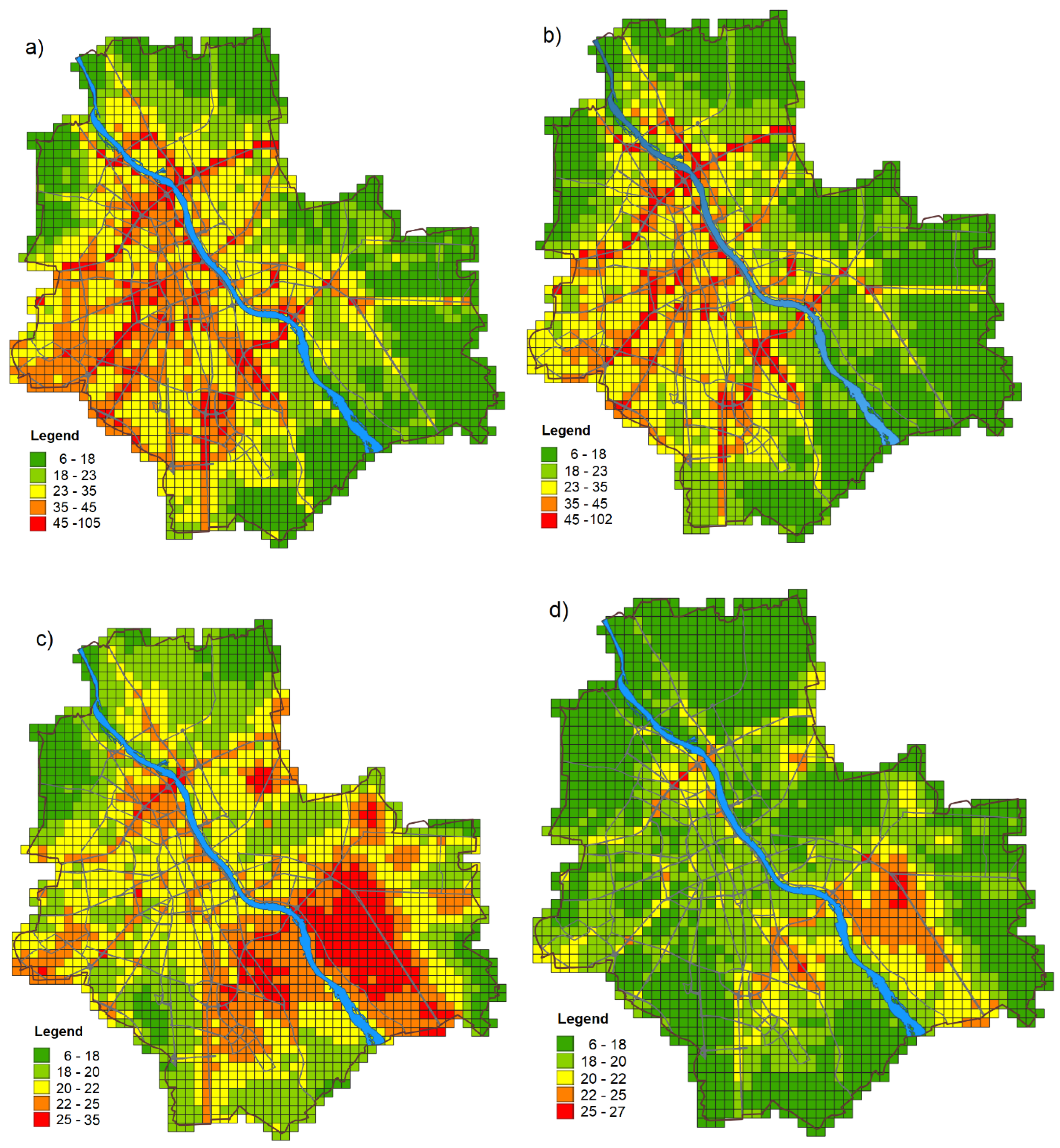

In addition, advanced work is underway to modernize the main transit roads running through Warsaw. One of these is an important S-N transit route (S7), where NOx concentrations reach maximum values (see

Figure 3a-b or

Figure 5a-b, for example) due to very high transit traffic, especially trucks, and lorries. According to the plan currently being implemented, the route across Warsaw are to be reconfigured to move all transit traffic out of the city boundaries. The implementation of the project, which is scheduled in the coming years, should bring significant improvements to this part of the city, which is located near the route.