Submitted:

25 July 2024

Posted:

26 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Design and Selection of Samples

2.1. Ethical Procedures

2.2. Questionnaire

2.4. Sample Size Estimation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2. Difference in Characteristics of Physical Health and Diet

3.3. Quality of Life Scores

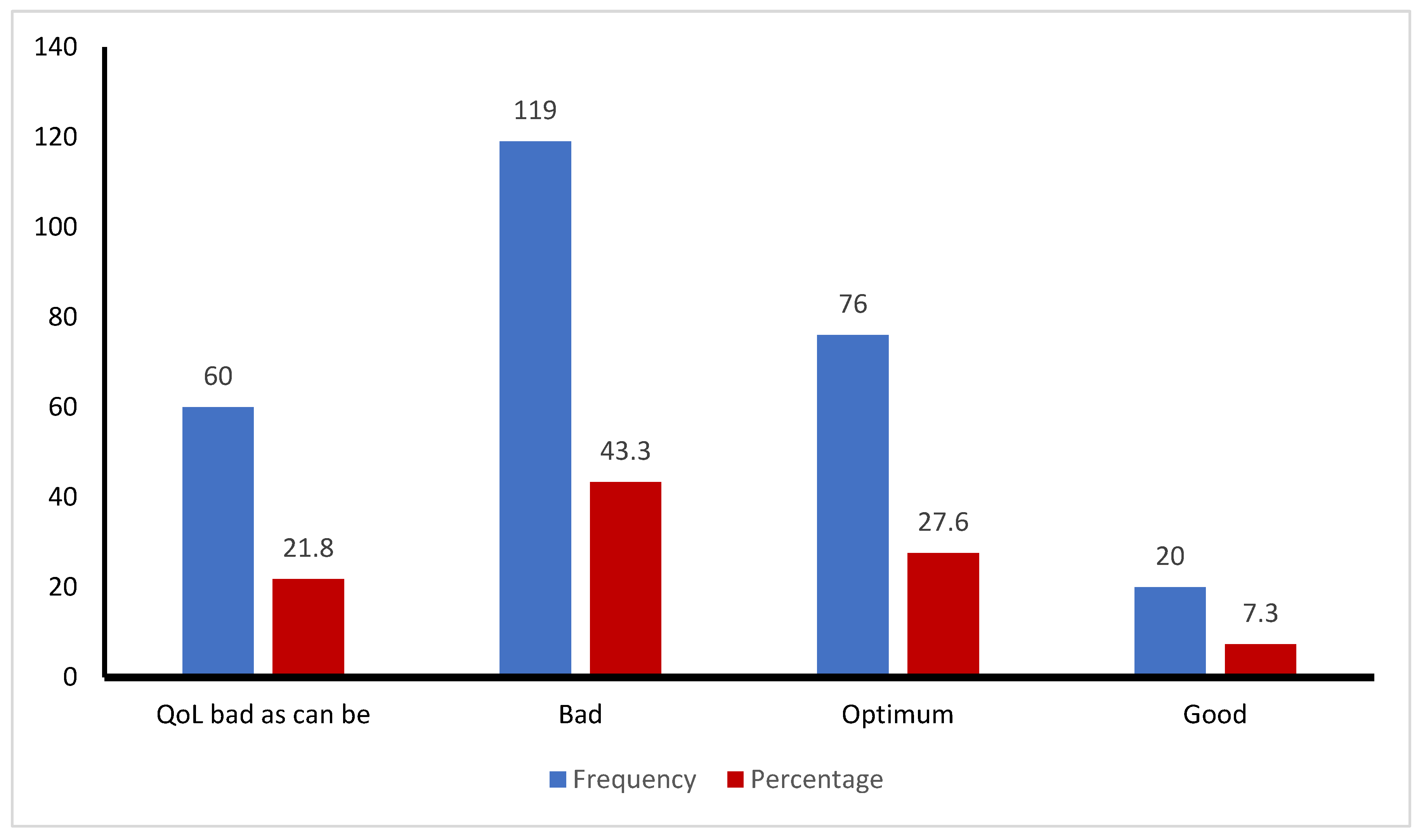

3.4. Distribution of Elderly People by Quality of Life (QoL) Categories

3.5. Correlation between Sociodemographic Factors and Quality of Life (QoL) Scores

3.6. Linear Regression Analysis to Predict Quality of Life

4. Discussions

4.1. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Participant ID No: /__/__/__/__/__/__/ | Date: | ||

| Name of the participant: | |||

| Address: | |||

| Section 1-Socio-demographic factor: | |||

| Serial No. | Question | Response | Code No. |

| 1 | What is your age? | /__/__/__/__/__/__/ Years | |

| 2 | Gender |

|

0 1 |

| 3 | What is your marital status? |

|

0 1 2 3 4 |

| 4 | What is your educational qualification? |

|

0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 5 | What is your occupation? |

|

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 |

| 6 | If not retired or unemployed, monthly income from your occupation? |

Ta taka Ta taka |

|

| 7 | What is your monthly family income? |

Ta taka Ta taka |

|

| 8 | Where do you live? |

|

0 1 2 |

| Section 2-Physical health related factors: | |||

| Serial No. | Question | Response | Code No. |

| 9 | Height |

I inch I inch |

|

| 10 | Weight |

kg kg |

|

| 11 | BMI |

kg/m2 kg/m2 |

|

| 12 | How many meals do you have a day? |

|

|

| 13 | Do you include vegetables in your diet? |

|

0 1 2 3 |

| 14 | Do you include fruits in your diet? |

|

0 1 2 3 |

| 15 | Do you include fish or meat or egg or lentil in your diet? |

|

0 1 2 3 |

| 16 | Do you include milk and milk products in your diet? |

|

0 1 2 3 |

| 17 | How many glasses of water do you drink every day? |

|

|

| 18 | Your smoking status? |

|

0 1 2 |

| 19 | How much do you sleep per day? |

H hour H hour |

|

| Section 3-Institution and government related factors | |||

| Serial No. | Question | Response | Code No. |

| 21 | Do you receive any pension, old age allowance or NGO’s support? If yes, what kind of support do you get? |

|

0 1 2 3 4 5 |

| 22 | How much allowance do you get monthly? |

Ta taka Ta taka |

|

Appendix B

| Serial No. ________________ | ||||||

| We would like to ask you about your quality of life: | ||||||

| Please tick one box in each row. There are no right or wrong answers. Please select the response that best describes you/your views. | ||||||

| 1. Thinking about both the good and bad things that make up your quality of life, how would you rate the quality of your life as a whole? | ||||||

| Your quality of life as a whole is | Very good (1) | Good (2) |

Alright (3) |

Bad (4) | Very bad (5) | |

|

2. Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each of the following statements. (Tick one box in each row) | ||||||

| Life overall | ||||||

| 1 | I enjoy my life overall | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 2 | I am happy much of the time | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 3 | I look forward to things | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 4 | Life gets me down | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| Health | ||||||

| 5 | I have a lot of physical energy | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 6 | Pain affects my wellbeing | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 7 | My health restricts me looking after myself or my home | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 8 | I am healthy enough to get out and about | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| Social relationship | ||||||

| 9 | My family, friends or neighbors would help me if needed | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 10 | I would like more companionship or contact with other people | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 11 | I have someone who gives me love and affection | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 12 | I’d like more people to enjoy life with | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 13 | I have my children around which is important | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| Independence, control over life, freedom | ||||||

| 14 | I am healthy enough to have my independence | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 15 | I can please myself what I do | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 16 | The cost of things compared to my pension/income restricts my life | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 17 | I have a lot of control over the important things in my life | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| Home and neighborhood | ||||||

| 18 | I feel safe where I live | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 19 | The local shops, services and facilities are good overall | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 20 | I get pleasure from my home | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 21 | I find my neighborhood friendly | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| Psychological and emotional wellbeing | ||||||

| 22 | I take life as it comes and make the best of things | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 23 | I feel lucky compared to most people | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 24 | I tend to look on the bright side | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 25 | If my health limits social/ leisure activities, then I will compensate and find something else I can do | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| Financial circumstances | ||||||

| 26 | I have enough money to pay for household bills | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 27 | I have enough money to pay for household repairs or help needed in the house | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 28 | I can afford to buy what I want to | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 29 | I cannot afford to do things I would enjoy | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| Leisure and activities | ||||||

| 30 | I have social or leisure activities/hobbies that I enjoy doing | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 31 | I try to stay involved with things | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 32 | I do paid or unpaid work or activities that gives me a role in life | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 33 | I have responsibilities to others that restrict my social or leisure activities | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 34 | Religious, belief or philosophy is important to my quality of life | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

| 35 | Cultural/religious events/festivals are important to my quality of life | Strongly agree (1) | Agree (2) | Neither agree or disagree (3) | Disagree (4) | Strongly disagree (5) |

References

- United Nations. World Population Aging 2017 Highlights. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. United Nations, New York. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2017_Highlights.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Ghosh, D.; Dinda, S. Determinants of the quality of life among elderly: Comparison between China and India. International Journal of Community and Social Development 2020, 2, 71–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.R.; Zabeen, I.; Khanam, M.; Akter, R.; Ali, N. Healthcare-seeking experiences of older citizens in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023, 3, e0001185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabir, R.; Khan, H.T.; Kabir, M.; Rahman, M.T. Population aging in Bangladesh and its implication on health care. European Scientific Journal 2013, 9, 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHOQOL: Measuring Quality of Life. World Health Organization, 2012. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Uddin, M.A.; Soivong, P.; Lasuka, D.; Juntasopeepun, P. Factors related to quality of life among older adults in Bangladesh: A cross sectional survey. Nursing and Health Sciences. 2017, 19, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, J.; Rana, A.K.; Kabir, Z.N. Social capital and quality of life in old age: Results from a cross-sectional study in rural Bangladesh. Journal of Aging and Health 2006, 18, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, A.R. Health-related quality of life among older citizens in Bangladesh. SSM - Mental Health 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A. The psychometric properties of the older people′ s quality of life questionnaire, compared with the CASP-19 and the WHOQOL-OLD. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research 2009, 2009, 298950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.N.; Mondal, M.N.I.; Hoque, N.; Islam, M.S.; Shahiduzzaman, M.D. A study on quality of life of elderly population in Bangladesh. American Journal of Health Research 2014, 2, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, H.; Morgan, K.; Hickey, A.; Burke, H.; Savva, G. Quality of life and beliefs about ageing. Available online: https://tilda.tcd.ie/publications/reports/pdf/w1-key-findings-report/Chapter10.pdf, (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Carrard, S.; Mooser, C.; Hilfiker, R.; Mittaz Hager, A.G. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Swiss French version of the Older People’s Quality of Life questionnaire (OPQOL-35-SF). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares, J.; Cigler, H.; Vachkova, E. Czech version of OPQOL-35 questionnaire: The evaluation of the psychometric properties. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk-Suszek, M.; Kleinrok, A. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of people over 65 years of age. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jung, M.; Kang, M. Age-varing association between physical activity and health-related quality of life among U.S. adults: 1928. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2022, 54, 573–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Palaniyandi, S.; Palaniyandi, A.; Gupta, V. Health related quality of life among rural elderly using WHOQOL-BREF in the most backward district of India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 2022, 11, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.K.; Govil, D.; Biswas, S. Relationship between falls/injuries and quality of life among the elderly in India. Research Square 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, V.; Shirinbayan, P.; Akbari Kamrani, A.; Foroughan, M.; Taheri, P.; Sheikhvatan, M. Quality of life in elderly people in Kashan, Iran. Middle East Journal of Age and Ageing 2008, 5, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Netuveli, G.; Wiggins, R.D.; Hildon, Z.; Montgomery, S.M.; Blane, D. Quality of life at older ages: Evidence from the English longitudinal study of aging (wave 1). Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2006, 60, 357–363. [Google Scholar]

- Daely, S.; Nuraini, T.; Gayatri, D.; Pujasari, H. Impacts of age and marital status on the elderly’s quality of life in an elderly social institution. Journal of Public Health Research 2022, 11, jphr.2021.2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagargoje, V.P.; James, K.S.; Muhammad, T. Moderation of marital status and living arrangements in the relationship between social participation and life satisfaction among older Indian adults. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 20604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damor, K.L.; Sonkaria, L.K.; Kewalramani, S.; Sidhu, J.; Lal, S. A study to assess quality of life of elderly residing in field practice area of urban health training center of SMS medical college Jaipur. Global Journal For Research Analysis (GJRA) 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkiewicz, B.; Barnaś, E.; Kołpa, M. Senior education and the quality of life of women in different periods of old age. Journal of Education, Health and Sport 2022, 12, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAbedi, G.; Naji, A. Quality of Life among Elderly at Primary Health Care Centers in Al-Amara City. Kufa Journal for Nursing Sciences 2020, 10, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Crawford, J.D.; Reppermund, S.; Trollor, J.; Campbell, L.; Baune, B.T.; Sachdev, P.; Brodaty, H.; Samaras, K.; Smith, E. Body mass index and waist circumference predict health-related quality of life, but not satisfaction with life, in the elderly. Quality of Life Research 2018, 27, 2653–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, H.; Li, X.; Jing, K.; Li, Z.; Cao, H.; Wang, J.; Bai, L.; Gu, J.; Fan, X.; Gu, H. Association between body mass index and health-related quality of life among Chinese elderly - Evidence from a community-based study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magee, C.A.; Caputi, P.; Iverson, D.C. Relationships between self-rated health, quality of life and sleep duration in middle aged and elderly Australians. Sleep Medicine 2011, 12, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, T.F.; Sun, X.M.; Li, S.J.; Wang, Q.S.; Cai, J.; Li, L.Z.; Li, Y.X.; Xu, M.J.; Wang, Y.; Chu, X.F.; Wang, Z.D.; Jiang, X.Y. Associations of sleep duration and sleep quality with life satisfaction in elderly Chinese: The mediating role of depression. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 2016, 65, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | All participants (n = 275) | Male (n = 173) |

Female (n = 102) |

Chi-square | P - value |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 65.07 ± 5.5 | 65.78 ± 5.87 | 63.85 ± 4.49 | - | 0.002a |

| Marital status (%) | 22.72b | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 215 (78.2) | 156 (90.2) | 59 (78.2) | ||

| Unmarried | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | ||

| Widow/divorced | 56 (20.3) | 16 (9.2) | 42 (41.2) | ||

| Education (%) | 29.48c | <0.001 | |||

| No formal education | 115 (41.8) | 54 (31.2) | 61 (59.8) | ||

| Primary education (grades 1-5) | 53 (19.3) | 35 (20.2) | 18 (17.6) | ||

| Secondary education (grades 6-12) | 52 (18.9) | 35 (20.2) | 17 (16.7) | ||

| Higher Secondary | 15 (5.5) | 13 (7.5) | 2 (2.0) | ||

| Graduation | 26 (9.5) | 23 (13.3) | 3 (2.9) | ||

| Post-graduation | 14 (5.1) | 13 (7.5) | 1 (1.0) | ||

| Occupation (%) | 221.67c | <0.001 | |||

| Retired | 39 (14.2) | 36 (20.8) | 3 (2.9) | ||

| Farmer | 22 (8.0) | 22 (12.7) | 0 | ||

| Businessman | 23 (8.4) | 21 (12.1) | 2 (2.0) | ||

| Service holder | 36 (13.1) | 34 (19.7) | 2 (2.0) | ||

| Unemployed | 55 (20.0) | 51 (29.5) | 4 (3.9) | ||

| Housewife | 88 (32.0) | 0 | 88 (86.3) | ||

| Others | 12 (4.4) | 9 (5.2) | 3 (2.9) | ||

| Family monthly income (Taka)d | 2.0c | 0.57 | |||

| Below 20,000 | 72 (26.2) | 42 (24.3) | 30 (28.4) | ||

| 20,000 – 39,999 | 135 (49.1) | 90 (52.0) | 45 (44.1) | ||

| 40,000 – 59,999 | 53 (19.3) | 31 (17.9) | 22 (21.6) | ||

| 60,000 and above | 15 (5.5) | 10 (5.8) | 5 (4.9) | ||

| Monthly allowances received (%) | 0.22b | 0.64 | |||

| None | 206 (74.9) | 124 (71.7) | 82 (80.4) | ||

| Pension | 33 (12.0) | 28 (16.2) | 5 (4.9) | ||

| Freedom fighter allowance | 9 (3.3) | 5 (2.9) | 4 (3.9) | ||

| Old age allowance | 25 (9.1) | 14 (8.1) | 11 (10.8) | ||

| Disability allowance | 2 (7.0) | 2 (1.2) | 0 | ||

| Residence type (%) | 5.94c | 0.05 | |||

| Urban | 131 (47.6) | 91 (52.8) | 40 (39.2) | ||

| Sub-urban | 32 (11.6) | 21 (12.1) | 11 (10.8) | ||

| Rural | 112 (40.7) | 61 (35.3) | 51 (50.0) | ||

| Characteristics | All participants (n = 275) | Male (n = 173) |

Female (n = 102) |

Chi-square | P - value |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD | 24.36 ± 3.32 | 24.24 ± 2.97 | 24.56 ± 3.85 | 0.47 | |

| Underweight | 4 (1.5) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (2.0) | 0.73a | 0.39 |

| Normal | 170 (61.8) | 108 (62.4) | 62 (60.8) | ||

| Overweight | 83 (30.2) | 56 (32.4) | 27 (26.5) | ||

| Obese | 18 (6.5) | 7 (4.0) | 11 (10.8) | ||

| Eat vegetables | 0.005a | 0.94 | |||

| Daily | 109 (39.6) | 70 (40.5) | 39 (38.2) | ||

| Often | 99 (36.0) | 61 (35.3) | 38 (37.3) | ||

| Sometimes | 64 (23.3) | 39 (22.5) | 25 (24.5) | ||

| None | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | 0 | ||

| Eat fruits | 0.86b | 0.84 | |||

| Daily | 33 (12.0) | 22 (12.7) | 11 (10.8) | ||

| Often | 42 (15.3) | 24 (13.9) | 18 (17.6) | ||

| Sometimes | 171 (62.2) | 109 (63.0) | 62 (60.8) | ||

| None | 29 (10.5) | 18 (10.4) | 11 (10.8) | ||

| Eat fish, meat, egg or lentil | 0.21a | 0.65 | |||

| Daily | 109 (39.6) | 67 (38.7) | 42 (41.2) | ||

| Often | 83 (30.2) | 51 (29.5) | 32 (31.4) | ||

| Sometimes | 81 (29.5) | 55 (31.8) | 26 (25.5) | ||

| None | 2 (0.7) | 0 | 2 (2.0) | ||

| Drink milk or milk product | 1.40b | 0.71 | |||

| Daily | 57 (20.7) | 39 (22.5) | 18 (17.6) | ||

| Often | 36 (13.1) | 21 (12.1) | 15 (14.7) | ||

| Sometimes | 123 (44.7) | 78 (45.1) | 45 (44.1) | ||

| None | 59 (21.5) | 35 (20.2) | 24 (23.5) | ||

| Smoking status | 73.78b | <0.001 | |||

| Current smoker | 30 (10.9) | 30 (17.3) | 0 | ||

| Former Smoker | 56 (20.4) | 56 (32.4) | 0 | ||

| Never smoked | 189 (68.7) | 87 (50.3) | 102 (100.0) | ||

| Sleep duration per day | 0.06b | 0.97 | |||

| 3-5 hours | 89 (32.4) | 56 (32.4) | 33 (32.4) | ||

| 6-7 hours | 142 (51.6) | 90 (52.0) | 52 (51.0) | ||

| 8-9 hours | 44 (16.0) | 27 (15.6) | 17 (16.7) | ||

| Quality of Life (QoL), mean ± SD | 113.79 ± 16.50 | 116.41 ± 16.23 | 109.33 ± 16.06 | <0.001 | |

| Quality of Life (QoL) score categoriesc | 11.45b | 0.01 | |||

| Bad as can be (less than 99) | 60 (21.8) | 28 (16.2) | 32 (31.4) | ||

| Bad (100 – 119) | 119 (43.3) | 75 (43.4) | 44 (43.1) | ||

| Optimum (120 – 139) | 76 (27.6) | 54 (31.2) | 22 (21.6) | ||

| Good (140 – 159) | 20 (7.3) | 16 (9.2) | 4 (3.9) |

| Age | Gender | Marital status | Education | Occupation | Body Mass Index | Sleep duration | OPQOL-35 Score | ||

| Age | r | 1 | -0.170** | 0.114 | -0.035 | -0.106 | -0.013 | -0.031 | -0.128* |

| P | 0.005 | 0.058 | 0.569 | 0.080 | 0.836 | 0.612 | 0.034 | ||

| Gender | r | 1 | 0.288** | -0.316** | 0.596** | 0.047 | 0.004 | -0.208** | |

| P | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.434 | 0.953 | <0.001 | |||

| Marital status | r | 1 | -0.167** | 0.127* | 0.011 | -0.023 | -0.195** | ||

| P | 0.005 | 0.035 | 0.850 | 0.706 | 0.001 | ||||

| Education | r | 1 | -0.425** | 0.113 | 0.069 | 0.417** | |||

| P | <0.001 | 0.061 | 0.255 | <0.001 | |||||

| Occupation | r | 1 | -0.031 | 0.045 | -0.242** | ||||

| P | 0.614 | 0.462 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Body Mass Index | r | 1 | 0.033 | 0.159** | |||||

| P | 0.589 | 0.008 | |||||||

| Sleep duration | r | 1 | 0.195** | ||||||

| P | 0.001 | ||||||||

| OPQOL-35 Score | r | 1 | |||||||

| P | |||||||||

| Variablesa | β- coefficient | SE | P-value | 95% CI for β |

| Constant | 91.797 | 6.594 | ||

| Educational status | 3.957 | 0.585 | <0.001 | 2.81 to 5.11 |

| Sleep duration (h) | 4.332 | 1.30 | <0.001 | 1.77 to 6.89 |

| Marital status | -2.259 | 0.90 | 0.013 | -4.03 to -0.488 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 0.578 | 0.267 | 0.031 | 0.054 to 1.103 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).