1. Introduction

Returnee migrant entrepreneurs make a significant contribution to their home country’s economy, society, and personal financial success (Gruenhagen & Davidsson, 2018; Macková & Harmáček, 2019; Naudé et al., 2017). They create jobs, wealth, innovation, and improve efficiency, benefiting society (Alshanty & Emeagwali, 2019). Returnees are more effective in managing their businesses compared to non-migrants (Barth & Zalkat, 2021; Batista et al., 2017; Henrik & Gruenhagen, 2021)and are more willing to take risks and be innovative, leading to their entrepreneurial success (Boudreaux et al., 2019; Naudé et al., 2017). In addition to financial capital, returnee migrant entrepreneurs bring back valuable knowledge, skills, and international networks that can strengthen entrepreneurial aspirations and capabilities. (Démurger & Xu, 2011; Kenney et al., 2013; Y. Liu & Almor, 2016; D. J. Wang, 2020). Their contributions are crucial in driving technological advancement and mitigating the effect of brain drain.(Cumming et al., 2015; Maria Hagan & Wassink, 2016; Zhou et al., 2016). Their broader impact includes nurturing innovation, job creation, and the cultivation of entrepreneurial culture. (Maria Hagan & Wassink, 2016; Qin et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2016). Recent research recognized returnee migrant entrepreneurs as agents of change and development within their communities. (Åkesson & Baaz, 2015; Akkurt, 2016; Riaño, 2023).

The success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs is the most crucial research area from theoretical and practical perspectives. Success can be measured in various ways, including financial performance, business sustainability, employment opportunity, innovation, skills and knowledge transfer, social contributions, and entrepreneurial satisfaction. (Danga et al., 2019; Fairlie & Fossen, 2018). Financial performance is often used as a proxy for the success of individuals and firms. However, the success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs remains complex, as these businesses tend to be smaller, develop more slowly, and operate in multifaceted environments. The fundamental view of Padiaychee (2016) and Svotwa et al. (2022) Suggests that the performance should be measured from different dimensions. This study focuses on the success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs. (Agyapong & Attram, 2019; Alvarez & Busenitz, 2008).

Identifying the specific success factors for returnee migrant entrepreneurs is not straightforward and requires exploration to determine what factors are essential in various contexts. Some factors may lead to business failure in one situation but contribute to success in another, indicating that research on entrepreneurial success factors remains inconclusive. (Akkurt, 2016; Bensassi & Jabbour, 2017; Paper, 2017). Existing studies have extended the success factors to include individual characteristics, entrepreneurial skills, experiences, financial resources, social networking, and government policies, and institutional support. (Akkurt, 2016; Gruenhagen, 2019; Gupta & Mirchandani, 2018; Teng et al., 2020; Terefe Alene, 2022).

The paradox of an entrepreneur’s characteristics is emphasized in various studies. Bai et al. (2017), Démurger and Xu (2011), and Yu et al. (2017), noted that an individual must have some distinctive characteristics to be an entrepreneur. Furthermore, Chao et al.(2017), Goldin (2016), and D. Lin et al. (2016a), explained the positive relationship between human capital and the success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs.

Government policies have been documented to significantly influence entrepreneurial success, including the availability of institutional support mechanisms. Studies have also identified numerous factors that contribute to the success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs across different regions, noting both supportive and inhibitive roles of government policies and institutional support (Armanios et al., 2016; Gruenhagen, 2019; Smallbone & Welter, 2012). Gruenhagen (2019) and Gorostiaga et al. (2019) Highlighted instances where government policies and institutional support acted as barriers to the success of returnee entrepreneurial. These challenges are particularly pronounced in emerging economies, where such mechanisms may be inadequate. (Bosma et al., 2012; Gorostiaga et al., 2019; Gruenhagen, 2019).

The entrepreneurial journey is significantly shaped by legal frameworks, local market conditions, and cultural adaptability. (Naudé et al., 2017). Guidance and counseling services are crucial in helping entrepreneurs navigate the regulatory environment, access resources, and develop effective business strategies. (Hashemi et al., 2019; W. Hu et al., 2022; H. Ma et al., 2018). The quality of the institutional environment in the home country also plays a pivotal role in entrepreneurial success (Bai et al., 2017; X. Liu et al., 2015). Bruton et al. (2010) Emphasize the critical influence of institutional environments on entrepreneurial success. Research has shown that government policies promoting entrepreneurship enhance confidence and motivation. (Darnihamedani et al., 2018), while incentives for innovation and risk-taking encourage entrepreneurial endeavors (Audretsch et al., 2022; Bao et al., 2022). However, despite their potential, returnee migrant entrepreneurs have faced challenges that can hinder their success. (Estifanos & Zack, 2020; Mohamed et al., 2022).

The revitalization and reform of Ethiopia’s economy hinge significantly on the business of returnee migrant entrepreneurs. These entrepreneurs encounter numerous challenges in Ethiopia, including limited access to financing, inadequate training and development, restrictive government policies, and an unsupportive institutional environment. (Dessalegn et al., 2020). For instance, Habtamu et al. (2017) Highlight how mental health issues can impede entrepreneurial endeavors among returnees, while Dejen and Tadese (2022) Emphasize challenges related to acculturation and reintegration that impact returnee entrepreneurs’ social and economic adjustment. These difficulties are exacerbated by ineffective governmental policies and institutional support, preventing many returnee entrepreneurs from realizing their full potential. Nicol et al. (2020) Underscore the necessity of robust institutional support and effective government policies, particularly in a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which poses additional challenges. Determinants influencing returnee migration decisions and livelihood sustainability have been identified by Chinkilo et al. (2023), suggesting targeted interventions could enhance entrepreneurial outcomes.

Despite these challenges, over 4.38 million Ethiopians living abroad have returned and made significant contributions to the country’s economic development. In 2021, Ethiopia’s GDP grew by 6.3% from the previous year, with returnee migrant entrepreneurs contributing approximately 1.5% to this growth (Quarterly Economic Profile, 2021). This sector has substantial opportunities to expand its impact among the economically active returnee migrant entrepreneur population. Their contributions could significantly improve opportunities and government support. The government plays a crucial role in enhancing the economic contributions of these entrepreneurs in Ethiopia (Dessalegn et al., 2020).

Ethiopia remains an understudied region in entrepreneurial literature, particularly regarding entrepreneurial success (Terefe Alene, 2022). This study aims to extend the understanding of entrepreneurial success factors, especially in developing countries (Akkurt, 2016; Gupta & Mirchandani, 2018). Through both theoretical research and empirical analysis, it was sought to address the question of whether factors such as individual characteristics, entrepreneurial skills, experiences, financial resources, social capital, government policies, and institutional support influence entrepreneurial success. Specifically, this study focuses on returnee migrant entrepreneurs from KSA to Ethiopia, particularly in the Oromia, Amahara, and Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples (SNNPR) of central Ethiopia regions. Therefore, the study aims to fill this gap by examining the success factors of returnee migrant entrepreneurs in Ethiopia and the mediating role of government policies and institutional support.

2. Research Objectives

The following are the specific objectives of the study.

Identify the key success factors for returnee migrant entrepreneurs

Analyze the role of institutional support such as financial services, training programs, and psychological support, for returnee migrant entrepreneurs

Investigate the mediating role of government policies and institutional support in returnee migrant entrepreneurial success

These specific objectives can guide the research, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the success factors and the role of governmental and institutional support in the entrepreneurial endeavors of returnee migrants in Ethiopia.

3. Literature Review

3.1. The Evolution of Return Migrant Entrepreneurial Success

Returnee entrepreneurs are individuals who spend a period abroad for study or work before returning to their homes to start a business (Drori et al., 2009; Filatotchev et al., 2009; Zahra & Wright, 2016). They leverage networks, skills, knowledge, and financial earnings accumulated abroad to initiate ventures back home (Wahba & Zenou, 2012). Entrepreneurship success encompasses various dimensions including business outcomes and personnel achievement. (Bensassi & Jabbour, 2017; W. Hu et al., 2022)(Rauch et al., 2009), reflecting theoretical advancements, empirical research, and economic changes in understanding factors influencing returnee migrants’ entrepreneurship. Key determinants of their business success include human capital. (Becker, 1962; & Goldin, 2016), social capital (Putnam, 1993), and institutional support (Minniti, 2008).

3.2. Theoretical Background

Barzelay and Scott (1997), Becker (1962), Bourdieu (1986), Neal and Rosen (2000), and Bruton et al. (2010) have highlighted shortcomings in research on returnee migrant entrepreneurs, such as lack of theoretical grounding, empirical focus, feminist analysis, and insufficient attention to government policies and institutional support. This study addresses these gaps by providing a theoretical framework based on the success factor perspective and lack of fit theory, examining the direct and indirect effects of the Ethiopian government policies and institutional support. The concept of “success factor” was introduced by Daniel (1961) in management literature, extending across various areas of business management (Hagos et al., 2019; Khandelwal & Ferguson, 1999; Wronka, 2013), crucial for evaluating industry performance (Akkurt, 2016; X. Lin & Tao, 2012).

3.2.1. Human Capital Theory

Human Capital Theory, introduced by Becker (1962) and expanded by Neal and Rosen (2000), underscore the importance of knowledge and skills acquired abroad as vital resources for economic growth in their home country (Y. Liu & Almor, 2016). Returnee migrants mitigate brain drain, foster innovation, and enhance technology. (Maria Hagan & Wassink, 2016; Zhou et al., 2016). International work experience enhances their human capital, crucial for cultivating a robust entrepreneurial ecosystem (Chao et al., 2017; D. Lin et al., 2016b). Intellectual capital from accumulated digital knowledge and innovative capability significantly impacts entrepreneurial ecosystems and returnee migrant entrepreneurial success (Popkova & Sergi, 2020; Valenti & Horner, 2019). Previous studies indicate these factors substantial influence on entrepreneurial success (Chatterjee et al., 2021; Rosado-Pinto & Loureiro, 2020).

3.2.2. Social Capital Theory

The Social Capital Theory, developed by Bourdieu (1986), Coleman (1988), and (Putnam, 2000), underscores the role of relationships and social networks in personal and professional domains. It emphasizes the importance of social networks and ties for accessing benefits (Portes, 2009), providing insights into returnee entrepreneurs’ ventures. International networks acquired abroad and local networks from domestic relationships are pivotal for returnee entrepreneurs (Portes, 2009). Returnee entrepreneurs leverage intangible assets in emerging economies to create business opportunities and competitive advantage (Dai & Liu, 2009). Social capital enhances competitive advantage through entrepreneurial endeavors (Aldaibat, 2017), with returnee migrants’ networks offering critical resources such as initial capital and international experience (Bensassi & Jabbour, 2017). W. Hu et al. (2022) explore how entrepreneurs’ psychological capital contributes to entrepreneurial success, indicating interactions between social capital, individual characteristics, knowledge sharing, opportunity identification, and entrepreneurial behavior (De Carolis & Saparito, 2006; Pruthi, 2014).

3.2.3. Resource-Based View (RBV) Theory

The Resource-Based View (RBV) theory, initially introduced by Penrose (2009), has been widely applied in the field of entrepreneurship (Bai et al., 2017; Filatotchev et al., 2009). RBV underscores the significance of firms’ resources, both tangible and intangible in shaping profitability, development, and survival (Agyapong & Attram, 2019; Alvarez & Busenitz, 2008). Within this framework, all resources are viewed as scarce, valuable, and difficult for competitors to replicate (Barney et al., 2001). RBV provides a strategic approach for firms to achieve sustained competitive advantage by leveraging underutilized resource capabilities (Apriyani et al., 2019). According to RBV, organizations should focus on developing valuable internal resources including human capital attributes, such as competencies, traits, skills, and abilities. These attributes are crucial and should be effectively leveraged, particularly by small businesses (Bhandari et al., 2022). Thus, this study applied a Resource-Based View (RBV) within the context of entrepreneurship.

3.2.4. Institutional Theory

Institutional theory describes the formal mechanism through which organizations establish legitimacy by conforming to institutional norms (Barzelay & Scott, 1997). Local government, as institutional entrepreneurs, form the foundation for regional entrepreneurship (Bruton et al., 2010b; Filatotchev et al., 2009; & Xing et al., 2018). Additionally, cultural norms, business models, and business incubators crucially, provide vital support for entrepreneurship development (Mondal et al., 2023; Watson et al., 2023). However, start-up entrepreneurial groups face challenges in various institutional settings, such as overcoming the market barrier and acquiring the necessary knowledge, as noted by (Nkonoki & Ericsson, 2010; & Teng et al., 2020). Moreover, Bai et al. (2017) and X. Liu et al. (2015), have highlighted direct links between institutional quality and the success of migrant entrepreneurs returning to China. The role of institutional and external resources in establishing new businesses is paramount (Muhamad et al., 2020). Institutional support is critical for the sustainability of community initiatives and enterprises (Di Vaio et al., 2022; Yi, 2021), with business incubators playing a significant role in supporting entrepreneurship (Watson et al., 2023).

3.3. Empirical Review and Hypothesis Development

2.3.1. Individual Characteristics

Individual characteristics, such as age, education level, and previous work experience play a pivotal role in the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants. Studies indicate that returnees with higher educational levels and substantial work experience are more likely to succeed in entrepreneurial ventures due to their enhanced skills and knowledge base (Abera, 2012; Bensassi & Jabbour, 2017). Furthermore, exposure to diverse cultures and business environments enhances adaptability and innovation capabilities among returnee migrants, contributing further to their entrepreneurial success (Naudé et al., 2017). Based on the above rationales, the following hypothesis is posited:

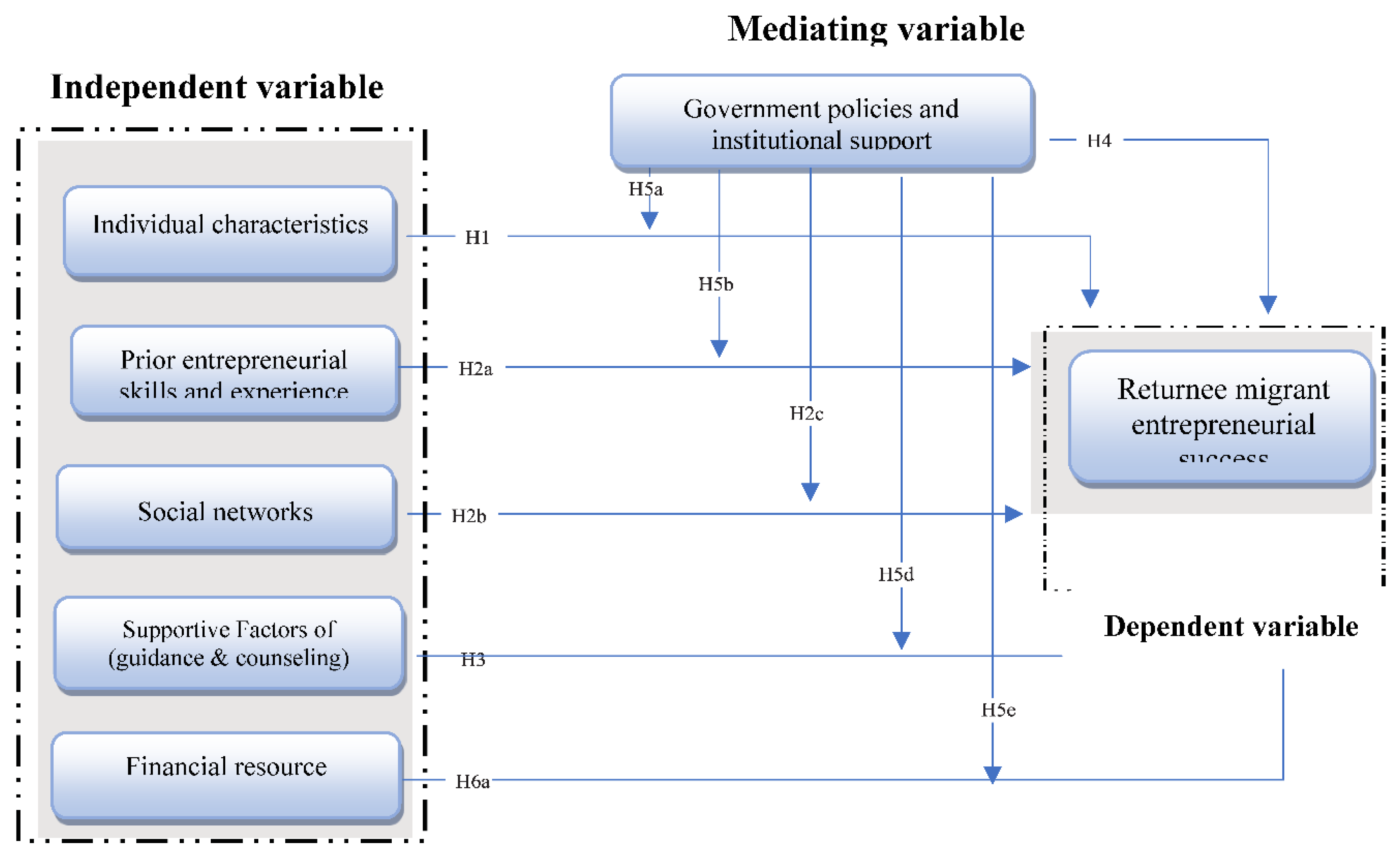

Hypothesis 1: Individual characteristics positively influence the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants.

2.3.2. Prior Entrepreneurial Skills and Experiences

Returnee migrant entrepreneurs often bring back skills and experiences acquired abroad that are crucial for entrepreneurship (Habtamu et al., 2017; Naudé et al., 2017). Research indicates that these skills - technological expertise, managerial capabilities, and cross-cultural awareness significantly enhance entrepreneurial success (Y. Liu & Almor, 2016; Maria Hagan & Wassink, 2016). Studies by Chao et al. (2017) and Huang et al. (2022) demonstrate that working abroad enhances the development of human capital. Z. Ma (2002b) suggests that return migrants are more likely to acquire new skills, change occupations, and start businesses due to their migration experiences. Additionally, returnees may have gained higher education or commercial business knowledge while abroad, aiding business start-ups (Dai & Liu, 2009; Kenney et al., 2013).

Carranza et al. (2018) emphasize that international exposure enhances entrepreneurial capabilities. Furthermore, previous entrepreneurial experience equips entrepreneurs to identify and exploit opportunities, evaluate industry trends, and understand customer needs and competitors (Shakeel et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2008). Based on these insights, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Prior entrepreneurial skills and experience positively influence the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants.

2.3.3. Social Capital

Social capital, encompassing networks, relationships, and social ties, plays a crucial role in entrepreneurial activities. Research by Dai and Liu (2009) and Aldaibat (2017) suggests that returnee migrants leverage their international networks to access resources such as business partners, mentors, and market information, enhancing their entrepreneurial opportunities and business success (Shakeel et al., 2020). Social capital helps build trust, foster collaboration, and expand business opportunities, thereby contributing to entrepreneurial success (Boudreaux et al., 2019). Moreover, social capital positively influences overall company success and business expansion (Bandera & Thomas, 2017; Kim & Lee, 2022). Unique sources of social capital are particularly noted among innovative entrepreneurs (Bandera & Thomas, 2017; Del Bosco et al., 2021). Drawing from this literature, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3: Social capital including international networks and strong local relationships positively influences the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants.

2.3.4. Supportive Factors: Guidance And Counseling

Psychological support, including mentorship, motivation, and emotional support, significantly influences the entrepreneurial journey of returnee migrants (George, 2018). Guidance and counseling provide essential psychological and professional support, enhancing entrepreneurial success (Habtamu et al., 2021; W. Hu et al., 2022). Practical advice, mentorship, and professional development opportunities offered through guidance help navigate business environments understand regulations, and develop strategies (H. Ma et al., 2018; Soomro et al., 2019). Structured guidance from mentors, business advisors, or training programs leverages expert knowledge (Fong et al., 2007). Counseling offers emotional support, boosts self-confidence, reduces anxiety, and promotes a positive outlook (Wangari, 2017). A comprehensive approach to guidance and counseling addresses both practical and emotional needs, leading to improved business performance, innovation, and sustainability (Busza et al., 2017; Danga et al., 2019; Mohamed et al., 2022). Based on these arguments, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4: Supportive factors, including guidance and counseling support, positively influence the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants.

2.3.5. Financial Resources

Financial capital, provided through equity, loans by formal institutions like banks, and informal sources such as family and friends, is essential for entrepreneurship (Dheer, 2018). Incubators also serve as significant sources of financial capital (Bandera & Thomas, 2017; Del Bosco et al., 2021). For returnee entrepreneurs, sufficient financial capital is often necessary for business creation and success (Block et al., 2017). Returnee migrant entrepreneurs perform better when they have access to financial resources (George, 2018). Challenges in securing capital due to unfamiliarity with local financial systems are common among returnees (Chao et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2016). Adequate financial support is crucial to overcome these barriers and ensure the profitability and sustainability of their business. Sufficient working capital enables the use of advanced technology, enhancing productivity and quality (Danga et al., 2019; Kamunge & Tirimba, 2014; Kanapathipillai & Azam, 2019). Entrepreneurs with inadequate initial capital often experience lower profits and survival rates compared to those with sufficient funding (Wangari, 2017). Therefore, limited access to adequate financial resources significantly hinders entrepreneurial success (Blanchflower & Oswald, 1990; Block et al., 2017). Based on this discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 5: Access to financial resources positively influences the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants.

2.2.5. The Mediating Role of Government Policies and Institutional Support

Government policies and institutional frameworks significantly influence entrepreneurial success by providing essential infrastructure, regulatory support, and market access. According to Resource-Based Theory, policies offering critical resources can enhance a company’s competitive advantage (Barney et al., 2001). These policies support entrepreneurial innovation, networks, technological expertise, and skills essential for gaining a competitive edge. However, without adequate entrepreneurial resources, these capabilities may not fully meet the evolving demands of entrepreneurial activities (Zeng et al., 2010).

Research by Filatotchev et al. (2009) and Levie and Autio (2008), highlights the role of supportive policies in facilitating entrepreneurship, while institutional support structures mitigate risks and provide legitimacy to entrepreneurial endeavors (Aidis et al., 2012). Drori et al. (2009) argue that these efforts also facilitate access to expertise, networks, and financial support crucial for success.

Institutional theory, as articulated by W. R. Scott (1999), emphasizes the impact of normative, regulatory, and cognitive institutions on entrepreneurial outcomes. Wright et al. (2008), further stress that supportive policies bridge the gap between individual capabilities and market demands. Based on the extensive literature, the following hypothesis is posited:

Hypothesis 6:

Government policies and institutional support positively mediate the relationship between (a) individual characteristics, (b) prior entrepreneurial skills and experience, (c) social network, (d) financial resources, and (d) supportive factors with the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants.

Using the success factor approach and existing literature, we have visualized the conceptual model shown in

Figure 1

4. Research Methodology

A quantitative research approach was employed to ensure a comprehensive analysis and explain causal relationships. Quantitative research, which quantifies data with statistical testing (Payne & Payne, 2004), was utilized due to a sufficient sample size with a response rate exceeding 30% (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). This method involved surveys and data collection using predetermined instruments (Creswell, 2014; Creswell & Creswell, 2017). The quantitative analysis employed Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to assess the credibility and validity of success factors, while SEM evaluated the relationship between these factors and entrepreneurial success. This study contributes to the entrepreneurship literature by extending the use of quantitative research methods (Akkurt, 2016; Gupta & Mirchandani, 2018; Terefe Alene, 2022).

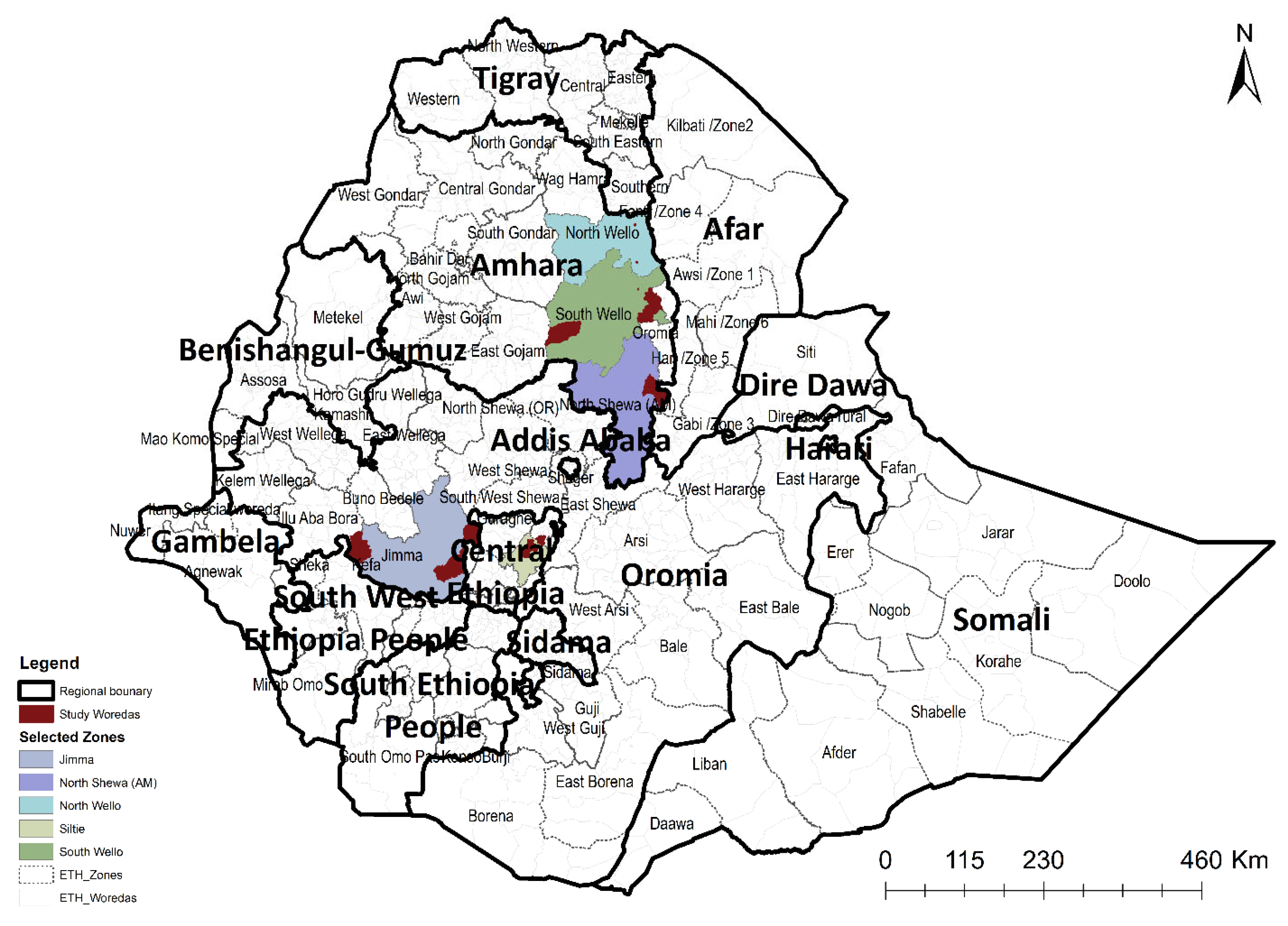

3.1. Study Area

In Ethiopia, specific woredas and zones have been identified as prominent places of origin for returnee migrants from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, who have started their businesses. This determination is based on IOM data analyzed between March 2017 and August 2020. These regions include the Amhara region: North Wollo (Kobo, Haike, and Mersa) and South Wello (Borena, Kalu, and Mekane-Selam); the Oromia region: Jimma zone (Sigmo, Omo Nada, and Sokoro), and central Ethiopia’s Silte zone (Silte and Werabe) (SNNPR).

These locations were selected due to high rates of entrepreneurial activity among returning migrants during the specified period.

3.1. Sample Size and Sampling Techniques

A simplified technique was used to determine the sample size for a study, aiming for a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error (Oakland, 1953). The study focused on 265,393 migrants who returned from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and are currently engaged in business activities in the Amhara (127,814), Oromia (125,234), and central Ethiopia of (SNNPR) (12,345) regions. The sample size of 399 was distributed evenly across these areas. Snowball sampling within zones and districts was employed for sample recommendation and selection, using purposive sampling methods as proposed (Goodman, 1961), deemed suitable for challenging sample acquisition situations.

3.2. Instrument Development

The survey instrument consists of three sections. The first section gathered demographic information including location, age, gender, education level, marital status, and previous entrepreneurial experience. The second section focused on six latent constructs related to success factors of returnee migrant entrepreneurs: individual characteristics, prior entrepreneurial skills and experience, social network, financial resources, and supportive factors (guidance & counseling. The third section assessed the role of government policies and institutional support in influencing entrepreneurial success. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

3.3. Questionnaire Pretest, Procedure, and Participants

The questionnaire underwent a pretest to validate its face validity and reliability, incorporating feedback to refine the final draft. Enumerators were trained in using a smartphone application for data collecting before distributing the questionnaire to thirty migrants in the Oromia, Amhara, and central Ethiopia’s (SNNPR) regions. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents before data collection. The consent form explained the study’s purpose and assured respondents of confidentiality and the use of data solely for academic purposes. Data was collected using the KoboToolbox platform, and 390 returnee migrants participated via mobile application in specific zones and woredas.

3.4. Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Gondar’s, School of Management and Public Administration’s ethical review board to ensure respondent protection. Support letters were secured from regional offices and relevant departments. Participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, duration, required samples, and data collection methods before obtaining their informed written consent. They were assured of confidentiality, voluntary participation, and their right to withdraw or skip uncomfortable questions without repercussions. There were no inducements or hidden agendas involved.

4. Results

Out of 399 distributed questionnaires to returnee migrants who had started businesses, 390 were completed and returned accurately, resulting in a 97.5% response rate. Kline (1998) documented that SEM allows for the simultaneous testing of multiple variables and has proven statistically effective. We utilized PLS-SEM due to its higher explanatory power for the variables involved (Henseler, 2018). PLS-SEM has also previously been employed for path analysis (Nitzl et al., 2016) and theory confirmation (Ringle et al., 2020). PLS-SEM offers several advantages over traditional SEM in various situations typical in social sciences research, and it is a complementary modeling approach to SEM. Conversely, the use of PLS-SEM among success factors and the success of returnee migrant entrepreneurial has a considerable theoretical contribution and extends the results of the given studies.

Table 1.

Details of the measure.

Table 1.

Details of the measure.

| Variables |

Items |

Literature sources |

Scale type |

| Individual characteristics |

Creativity, knowledge, innovation, the decision to return, and entrepreneurial skills |

Hajizadeh and Zali (2016)

Darnihamedani (2016)

Wei and Zhu (2020) |

1–5 Likert

Strongly disagree to strongly agree |

| Prior entrepreneurial skills and experience |

Entrepreneurial knowledge & skill

Business innovation

Prior entrepreneurial experience |

G. S. Becker (1962)

Shane and Venkataraman (2000)

Y. Liu and Almor (2016)

Wright et al. (2008)

Shakeel et al. (2020) |

1–5 Likert

Strongly disagree to strongly agree |

| Social network |

Social integration

Access to resources and information

Social groups or individuals |

(Zimmer, 1986)

Stuart and Sorenson (2005)

Bandera and Thomas (2017)

Kim and Lee (2022) |

1–5 Likert

Strongly disagree to strongly agree |

| Financial resources |

Availability of finance

Role of financial capital

Loan and Funding |

Blanchflower and Oswald (1990)

Block et al. (2017)

Dheer (2018) |

1–5 Likert

Strongly disagree to strongly agree |

| Supportive factors (guidance & counseling) |

Professional support

Family support

Mentors

Business advisors

Counselling |

George (2018)

Habtamu et al. (2021

W. Hu et al. (2022)

Fong et al. (2007)

Busza et al. (2017) |

1–5 Likert

Strongly disagree to strongly agree |

| The success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs |

Individual success

Company success |

Malebana and Mahlaole (2023)

Shi and Weber (2021) |

1–5 Likert

Strongly disagree to strongly agree |

| Government policies and institutional support |

Rules, regulations, and laws

Financial support

Training and development

Networking and mentorship

Psychological and emotional support |

Bosma et al. (2012)

Zhu and Kang (2013)

Gorostiaga et al. (2019) Gruenhagen (2019)

|

1–5 Likert

Strongly disagree to strongly agree |

Its application in examining the success factors and success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs makes significant theoretical contributions and extends previous studies’ findings.

Reliability and Validity

The reliability, validity, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient were utilized to assess the consistency of data, scales, and hypothesized relationships among variables. In

Table 2, Cronbach’s alpha values surpass the 0.7 threshold, indicating an acceptable scale reliability. Four primary tests were conducted: internal consistency reliability, item reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2011, 2019). Both internal consistency reliability and composite reliability (CR) exceed 0.7 (Hair et al., 2019; Nitzl et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2022). Furthermore, item reliability requires standardized loadings above 0.7 (with the lowest value at 0.818, p < .001), affirming precise measurement of constructs, as indicated by the rho_A values (Hair et al., 2011, 2019). The average extracted variance (AVE) values for latent variables exceed 0.5 (the lowest AVE was 0.510), as shown in

Table 3 (Kock & Hadaya, 2018). Therefore, it is concluded that the study’s scale and model are reliable and valid for analyzing the formulated hypotheses.

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell-Larcker Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) ratios to test (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Following Henseler et al. (2015) criteria, the HTMT ratios indicated acceptable discriminant validity, with all values below the threshold of 0.85. The square root of each construct AVE exceeded its correlation with other constructs (see

Table 3). Diagonal elements in bold represent the square root of variance shared between constructs and their dimension (AVE), while off-diagonal elements indicate correlations among constructs.

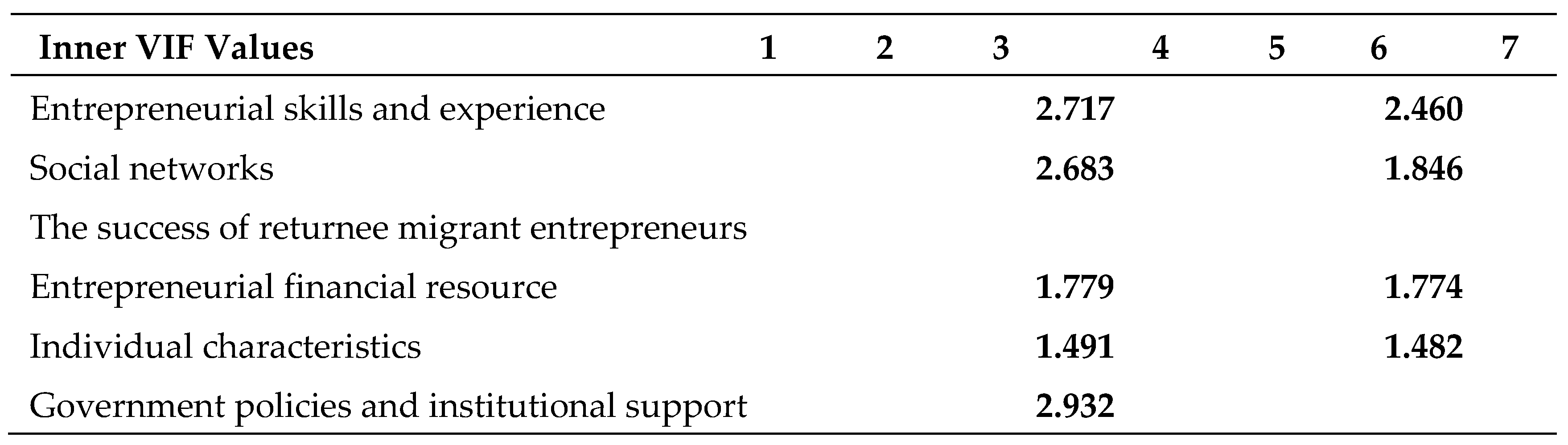

To check for multicollinearity, variance inflation factors (VIFs) were examined. Following recommendations by Aiken et al. (1991), Hair et al. (2019), Jony and Serradell-López (2021), and Purwanto (2021), VIF values were found to be less than 3, indicating no issues with multicollinearity (see

Table 5). These results confirm that the model exhibits excellent discriminant validity and no multicollinearity (Sharma et al., 2021). (see the values in

Table 3).

Table 4.

Discriminant validity of constructs using Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT).

Table 4.

Discriminant validity of constructs using Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT).

| Variables |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

| Entrepreneurial skills and experience |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Social networks |

0.731 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs |

0.230 |

0.238 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Financial resource |

0.328 |

0.272 |

0.391 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Individual characteristics |

0.386 |

0.179 |

0.440 |

0.477 |

|

|

|

|

| Government policies and institutional support |

0.772 |

0.822 |

0.353 |

0.280 |

0.314 |

|

|

|

| Support Factors (guidance and counseling) |

0.654 |

0.397 |

0.398 |

0.197 |

0.487 |

0.494 |

0.273 |

|

Collinearity Statistics (VIF)

Table 5.

Collinearity statistics (inner VIF values).

Table 5.

Collinearity statistics (inner VIF values).

Assessment of Structural (Outer) Model

The PLS-SEM was employed to estimate the parameters in the structural equation model. According to Henseler et al. (2015), the evaluation of both the measurement and structure model is integral to the PLS path model. The assessment of the measurement model involves examining outer weights to determine each construct’s contribution to the latent variables. A key focus in structural model evaluation is the R2 coefficient of the endogenous latent variables (Nitzl et al., 2016). As established by Hair et al. (2011), thresholds for R2 are .75 (substantial), .50 (moderate), and .25 (weak), while Chin (1998) suggested thresholds of 0.67 (substantial), 0.33 (moderate), and 0.19 (weak).

Bootstrapping was employed in PLS-SEM to assess p-values and determine the significance of path coefficients. Additionally, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) values were used to evaluate the structural model, with values ideally below 0.08 for sample sizes greater than 100 (Henseler et al., 2015). Bootstrap-based tests for overall model fit (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015; Henseler, 2018) confirmed a significant model fit (SRMR = 0.089), indicating the model’s appropriateness (Henseler et al., 2015; L. Hu & Bentler, 1998).

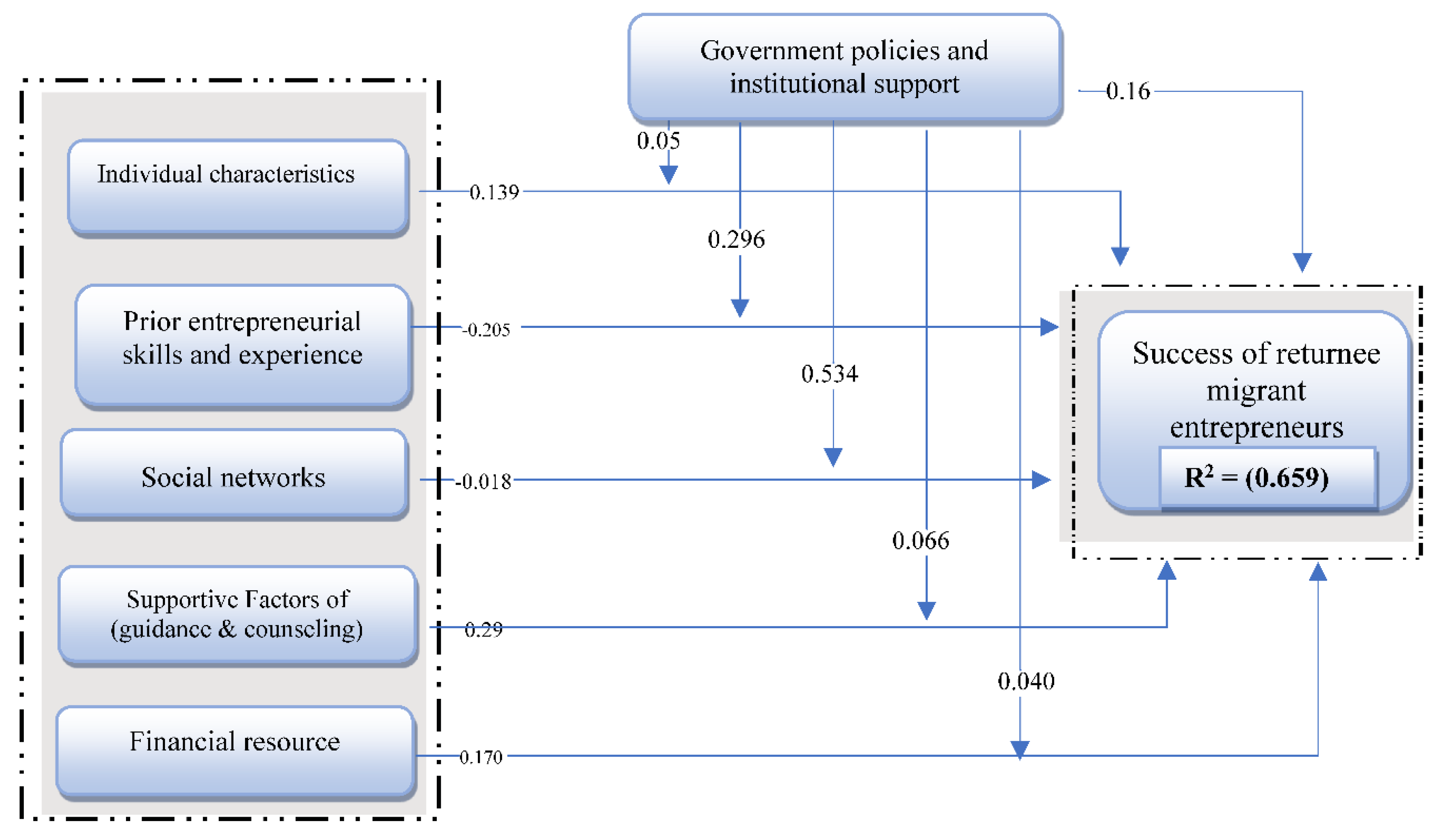

As shown in

Table 6, the R2 values for “Success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs” and “Government policies and institutional support” were found to be 0.262 and 0.089, respectively. Furthermore, Q2 values greater than zero indicate the predictive relevance of the study model, with results within the significance threshold (see

Table 6)

Figure 3.

Results of the structural model for success factors and success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs.

Figure 3.

Results of the structural model for success factors and success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs.

4.3.1. Hypothesis Testing

The results are summarized in

Figure 2, which also shows path coefficients, standard deviations, t-statistics, and p-values.

The PLS-SEM analysis results indicate that (H1a), testing the direct effects between individual characteristics and entrepreneurial success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs, shows a significant positive influence (β =0.139, t= 2.356, p =0.019). Thus, H1a was supported. Conversely, (H5a) the direct effects between individual characteristics and government policies and institutional support, show a non-significant relationship (β =0.057, t= 1.723, p =0.086). This suggests that personal traits and qualities play a crucial role in shaping the success of returnee migrants in entrepreneurship. Higher education levels are associated with increased creativity and the ability to generate innovative business ideas, contributing to entrepreneurial success. This finding aligns with previous research (Alarcón & Ordóñez, 2016; Croitoru, 2020; Habtamu et al., 2017; Mohamed et al., 2022; Soomro et al., 2019; Thang, 2022; X. Wei & Zhu, 2020). On the other hand, the result of individual characteristics on government policies and institutional support are non-significant statistically. These results contradict previous studies that highlighted the importance of these factors for entrepreneurial success (Qin et al., 2017; Wahba & Zenou, 2012; Yu et al., 2017).

The results show that entrepreneurial skills and experience (H2a) positively influence government policies and institutional support (β = 0.296, t=5.638, p=0.000). However, government policies and institutional support do not significantly affect the success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs (β = 0.168, t=1.582, p=0.114). Prior work experience enables entrepreneurs to identify opportunities and apply transferred knowledge effectively, contributing to their success. This finding is consistent with previous studies (Bai et al., 2017; Naudé et al. 2017; Zhou et al. 2016). Experienced entrepreneurs are better equipped to direct institutional frameworks and benefit from supportive policies (Teng et al., 2020; Version, 2018; Y. Wei, 2022). These skills contribute to developing guidelines, policies, and laws through public-private partnerships, enhancing entrepreneurial success (Audretsch et al., 2022; Motoyama & Knowlton, 2016).

The results show that (H2b) social network has a non-significant relationship with the success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs (β = -0.018, t= 0.203, p = 0.839), contrary to expectations. This suggests that social networks have a non-significant relationship the entrepreneurial success among returnee migrants in Ethiopia, this finding contradicts previous research (Aldaibat, 2017; Bai et al., 2017; Batjargal, 2007; X. Y. Wang et al., 2020), which typically highlights the positive influence of social networks on entrepreneurial success. It implies that other variables may be more influential in this context, or the quality and nature of available social networks for returnee migrants may not be supportive or effective. This suggests that strong social networks facilitate access to and understanding of institutional support and government programs. This result is consistent with previous research (Teng et al., 2020; Y. Wei, 2022), highlighting social networks as information hubs that trigger opportunities and contribute to venture success.

The results show that support factors, such as guidance and counseling (H3a), significantly and directly affect the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants (β = 0.534, t = 9.670, p = 0.000). Thus, H3a was supported. However, the mediating effects of these support factors through government policies and institutional support on the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants were non-significant (β = 0.066, t = 1.939, p = 0.053). Therefore, H5d was not supported. This partial mediation suggests that support factors directly influence entrepreneurial success strongly, the indirect pathway via government policies was non-significant. Services like peer learning experiences, group workshops, and one-on-one counseling are crucial for helping returnee migrants overcome challenges, make informed decisions, and succeed in their entrepreneurial ventures. This finding is consistent with the previous studies (Danga et al., 2019; Mohamed et al., 2022; Soomro et al., 2019), which emphasizes the importance of structured guidance programs in improving business performance and growth. It suggests that while entrepreneurs, the direct contribution of guidance and counseling to policy effectiveness is insignificant. This contradicts the previous studies (Wright et al., 2008), which emphasized the role of support systems in shaping institutional frameworks. These findings are consistent with studies by George (2018), Habtamu et al. (2021), and W. Hu et al. (2022), underscore that psychological support, such as mentorship and motivation, significantly influences returnee migrants.

Moreover, (H6a) financial resources have significant and positive effects on the success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs with (β = 0.170, p = 0.006). Thus, H6a was supported. However, the indirect effects of government policies and institutional support on the relationship between financial resources and the success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs (H5e) were non-significant (β = 0.040, p = 0.433) indicating partial mediation in the model, and thus, H5e was supported. This underscores the crucial role of financial capital in fostering business growth and investment in innovative ventures. These findings aligned with the previous research (Bandera & Thomas, 2017; Del Bosco et al., 2021; Dheer, 2018), which highlights the importance of financial support for sustainable business operations and development. However, it suggests that financial resources significantly enhanced the impact of government policies on entrepreneurial success, contrary to previous findings (Wright et al., 2008). These results highlight the complexities of how different factors contribute to the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants.

(H5e) testing the direct effects between financial resources showed a non-significant relationship on the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants (β = 0.066, t = 1.939, p = 0.053). While, the direct effects of government policies and institutional support on the relationship between social networks and the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants (H2c) were significant with (β=0.534*, t = 9.670, p=0.000). Therefore, it was concluded that government policies and institutional support partially mediated the relationship between social networks and the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants. Similarly, there is a non-significant direct effect of individual characteristics and supportive factors like guidance and counseling on the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants (β=0.057ns, p=0.086; β=0.066ns, p=0.053) respectively.

Whereas, the direct effects of government policies and institutional support on the relationship between entrepreneurial skills and experience and the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants were significant with (β = 0.296, t=5.638, p=0.000). Hence, H5b was supported. This concluded that government policies and institutional support partially mediated the relationships between entrepreneurial skills and experience and the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants. These findings underscore the need for tailored policy interventions and a strengthened entrepreneurial ecosystem to effectively support and enhance the success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs. However, returnee migrant entrepreneurs continue to face challenges with financial resources, individual characteristics, and support factors such as guidance and counseling problems at the national and regional levels due to due to unfamiliarity with local financial systems, limited access to formal funding, inadequate or poorly tailored based psychological support services (Dessalegn et al., 2020; Estifanos & Zack, 2020; Mohamed et al., 2022; Version, 2018).

Table 7.

Hypothesis constructs (path coefficients, Mean, T Statistics (O/STDEV), p values).

Table 7.

Hypothesis constructs (path coefficients, Mean, T Statistics (O/STDEV), p values).

| Path relationship |

Beta |

Sample Mean (M) |

Standard Deviation (STDEV) |

T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) |

Hypothesis |

P Values |

Decision |

| “Success factors Success” → “Success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Individual characteristics |

0.139* |

0.141 |

0.059 |

2.356 |

H1a |

0.019 |

Supported |

| Entrepreneurial skills and experience |

-0.205* |

-0.208 |

0.088 |

2.335 |

H2a |

0.020 |

Supported |

| Social networks |

-0.018 ns

|

-0.014 |

0.090 |

0.203 |

H2b |

0.839 |

Not supported |

| Support Factors, such as guidance and counseling |

0.296* |

0.300 |

0.065 |

4.547 |

H3a |

0.000 |

Supported |

| Financial Resource |

0.170* |

0.173 |

0.061 |

2.765 |

H6a |

0.006 |

Supported |

| Government policies and institutional support |

0.168ns

|

0.166 |

0.106 |

1.582 |

H4a |

0.114 |

Not supported |

| Entrepreneurial skills and experience -> Government policies and institutional support -> Success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs |

0.296* |

0.296 |

0.053 |

5.638 |

H5b |

0.000 |

Supported |

| Social networks -> Government policies and institutional support -> Success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs |

0.534* |

0.533 |

0.055 |

9.670 |

H2c |

0.000 |

Supported |

| Entrepreneurial financial resource -> Government policies and institutional support -> Success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs |

0.040ns

|

0.037 |

0.050 |

0.786 |

H5e |

0.433 |

Not supported |

| Individual characteristics -> Government policies and institutional support -> Success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs |

0.057ns

|

0.060 |

0.033 |

1.723 |

H5a |

0.086 |

Not supported |

| Government policies and institutional support -> Success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs |

0.168ns

|

0.166 |

0.106 |

1.582 |

H4b |

0.114 |

Not supported |

| Support factors such as guidance and counseling -> Government policies and institutional support |

0.066ns

|

0.068 |

0.034 |

1.939 |

H5d |

0.053 |

Not supported |

5. Conclusions

The study concludes that the success of returnee migrant entrepreneurs in Ethiopia is significantly influenced by entrepreneurial skills, experience, and financial resources. Individual characteristics, while crucial for entrepreneurial success, do not significantly impact government policies and institutional support. Conversely, entrepreneurial skills and experience positively influence these policies, though the policies themselves do not directly affect entrepreneurial success. Social networks, although not directly significant, positively impact success when mediated by government policies and institutional support. Professional guidance and counseling are vital for success but do not enhance policy effectiveness. Financial resources are essential for business growth but do not significantly influence policy efficacy. These findings highlight the need for targeted policy reforms and a strengthened entrepreneurial ecosystem. Experienced returnee entrepreneurs’ involvement in community dialogue and policy reform is key to building a robust support system. Future research should explore tailored policy interventions to address the challenges faced by returnee entrepreneurs, including financial access and psychological support services.

Theoretical Contributions

This study extends the success factors theory to include returnee migrant entrepreneurs in Ethiopia, enriching our understanding of entrepreneurial dynamics (Alarcón & Ordóñez, 2016; Amare & Honig, 2023; Croitoru, 2020). The proposed model elucidates key drivers shaping the business perspectives of returnee migrant entrepreneurs (Akkurt, 2016; Daniel, 1961; De Haas, 2014). It categorizes success factors into five clusters: individual characteristics, prior entrepreneurial skills and experiences, social networks, financial resources, and supportive factors. This classification offers a novel framework for analyzing success factors in returnee migrant entrepreneurship literature. Additionally, by exploring the mediating role of government policies and institutional support, the study contributes to the lack of fit theory, providing new insights into how external factors influence entrepreneurial success in Ethiopia. These contributions enhance the theoretical foundation for future research in returnee migrants and entrepreneurship.

Practical Implications

The findings provide valuable insights for policymakers, support organizations, and returnee migrant entrepreneurs. Firstly, fostering the development of returnee migrant entrepreneurs’ unique qualities—such as creativity, knowledge, and decision-making skills—should be prioritized through targeted training initiatives and educational opportunities. Secondly, the importance of prior entrepreneurial skills and experience underscores the need for tailored mentorship opportunities and business expertise programs integrated into institutional frameworks. Thirdly, effective utilization of social networks can improve access to institutional support and policies. Policymakers should encourage initiatives that facilitate access to relevant information and resources. Additionally, while financial resources are critical, existing policies may not effectively connect financial support with business success. Tailored financial programs that address the specific needs and challenges of returnee migrant entrepreneurs are essential. Addressing these areas can significantly enhance the entrepreneurial success of returnee migrants and support their sustainable business ventures.

Limitations and Future Research

Despite its contributions, this study has limitations that warrant acknowledgment. Firstly, its findings may have limited generalizability beyond Ethiopia due to the study’s exclusive focus on this context. Secondly, self-reported data from questionnaires could introduce response bias and social desirability bias. Thirdly, the cross-sectional design restricts causal inference, necessitating longitudinal research to explore the temporal dynamics of entrepreneurial success. Fourthly, while PLS-SEM was chosen for its suitability with complex models, complementary insights from covariance-based SEM or other methodologies could enrich future research. Moving forward, comparative studies across diverse regions, mixed-method approaches for robust data triangulation, and longitudinal designs are recommended. Qualitative inquiries could also deepen understanding of nuanced aspects of social networks and institutional support. These efforts would enhance the robustness and applicability of findings, guiding policy and practice to better support returnee migrant entrepreneurs globally.

Funding

The authors did not receive direct funding for this research.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to all the participants who took part in the survey, including returnee migrants, the project coordinator, the focal person, the job creation officer, the social and labor officer, and the migration protection officer. We also appreciate the diligent work of the enumerators in each woreda and zone.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Kassaye, B. D., Bayiley, Y. T., & Kindie, Z], upon reasonable request.

References

- Abera, A. (2012). Factors Affecting the Performance of Micro and Small Enterprises in Arada and Lideta Sub-Cities, Addis Ababa. Journal of Accounting and Finance, 2(4), 15–27.

- Agyapong, D., & Attram, A. B. (2019). Effect of owner-manager’s financial literacy on the performance of SMEs in the Cape Coast Metropolis in Ghana. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 67.

- Aidis, R., Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. M. (2012). Size matters: entrepreneurial entry and government. Small Business Economics, 39, 119–139.

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. sage.

- Åkesson, L., & Baaz, M. E. (2015). Africa’s return migrants: the new developers? Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Akkurt, E. (2016). Returnee Entrepreneurs-Characteristics and Success Factors. LEMEX Research Papers on Entrepreneurship, 1.

- Alarcón, S., & Ordóñez, J. (2016). Ecuador: return from migration and entrepreneurship in Loja. CEPAL Review, 2015(117), 65–81. [CrossRef]

- Aldaibat, B. (2017). The role of social capital in enhancing competitive advantage. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 6(4), 66–78.

- Alshanty, A. M., & Emeagwali, O. L. (2019). Market-sensing capability, knowledge creation and innovation: The moderating role of entrepreneurial-orientation. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, 4(3), 171–178. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S. A., & Busenitz, L. W. (2008). Journal of Management. [CrossRef]

- Amare, T. J., & Honig, B. (2023). Returnee entrepreneurial entry decisions among forced and voluntary returnees in Ethiopia: A comparative study. Africa Journal of Management, 9(2), 177–205. [CrossRef]

- Apriyani, Y., Haryono, S., & Eq, Z. M. (2019). The effect of self-learning, entrepreneurship competence and entrepreneurship orientation on micro business performance in the special province of Yogyakarta. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 10(10), 119–133.

- Armanios, D., Eesley, C., & Li, J. (2016). How entrepreneurs leverage institutional intermediaries in emerging economies to acquire public resources INTERMEDIARIES IN EMERGING ECONOMIES TO ACQUIRE PUBLIC RESOURCES. July. [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D. B., Belitski, M., Chowdhury, F., & Desai, S. (2022). Necessity or opportunity? Government size, tax policy, corruption, and implications for entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 58(4), 2025–2042.

- Bai, W., Johanson, M., & Martín Martín, O. (2017). Knowledge and internationalization of returnee entrepreneurial firms. International Business Review, 26(4), 652–665. [CrossRef]

- Bandera, C., & Thomas, E. (2017). Startup incubators and the role of social capital. 2017 IEEE Technology & Engineering Management Conference (TEMSCON), 142–147.

- Bao, A., Pang, G., & Zeng, G. (2022). Entrepreneurial effect of rural return migrants: Evidence from China. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(December), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Barney, J., Wright, M., & Ketchen Jr, D. J. (2001). The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. Journal of Management, 27(6), 625–641.

- Barth, H., & Zalkat, G. (2021). Refugee entrepreneurship in the agri-food industry: The Swedish experience. Journal of Rural Studies, 86, 189–197.

- Barzelay, M., & Scott, W. R. (1997). Institutions and Organizations. The British Journal of Sociology, 48(1), 161. [CrossRef]

- Batista, C., McIndoe-Calder, T., & Vicente, P. C. (2017). Return Migration, Self-selection and Entrepreneurship. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 79(5), 797–821. [CrossRef]

- Batjargal, B. (2007). Comparative Social Capital: Networks of Entrepreneurs and Venture Capitalists in China and Russia. Management and Organization Review, 3(3), 397–419. [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. S. (1962). This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title : Investment in Human Beings Volume Author / Editor : Universities-National Bureau Committee for Economic Research Volume Publisher : The Journal of. In The Journal of Political Economy (Vol. 5, Issue 2).

- Bensassi, S., & Jabbour, L. (2017). Return Migration and Entrepreneurial Success: An Empirical Analysis for Egypt. Global Labor Organization (GLO), 98. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/167590www.econstor.eu.

- Bhandari, K. R., Ranta, M., & Salo, J. (2022). The resource-based view, stakeholder capitalism, ESG, and sustainable competitive advantage: The firm’s embeddedness into ecology, society, and governance. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(4), 1525–1537.

- Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (1990). What makes a young entrepreneur?

- Block, J. H., Fisch, C. O., & Van Praag, M. (2017). The Schumpeterian entrepreneur: A review of the empirical evidence on the antecedents, behaviour and consequences of innovative entrepreneurship. Industry and Innovation, 24(1), 61–95.

- Bosma, N., Wennekers, S., & Amorós, J. E. (2012). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2011 Extended Report: Entrepreneurs and Entrepreneurial Employees Across the Globe. London: Global Entrepreneurship Research …, 1–239.

- Boudreaux, C. J., Nikolaev, B. N., & Klein, P. (2019). Socio-cognitive traits and entrepreneurship: The moderating role of economic institutions. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(1), 178–196.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. Teoksessa: Richardson, JG. Toim. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education.

- Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H. (2010a). Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 421–440.

- Bruton, G. D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H. L. (2010b). Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 34(3), 421–440. [CrossRef]

- Busza, J., Teferra, S., Omer, S., & Zimmerman, C. (2017). Learning from returnee Ethiopian migrant domestic workers: A qualitative assessment to reduce the risk of human trafficking. Globalization and Health, 13(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Carranza, E., Dhakal, C., & Love, I. (2018). Female Entrepreneurs: How and Why are They Different? Other Papers, 20, 64. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31004.

- Chao, X., Lingping, W., & Wenping, S. (2017). Migrant working experience, social capital and entrepreneurship of migrant workers returning home: Evidence from CHIPS data. Journal of Finance and Economics, 43(12), 30–44.

- Chatterjee, S., Chaudhuri, R., & Vrontis, D. (2021). Does data-driven culture impact innovation and performance of a firm? An empirical examination. Annals of Operations Research, 1–26.

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336.

- Chinkilo, A. F., Kassa, T. M., & Teshome, T. T. (2023). Determinants of Return Migration Decision among Ethiopian International Returnees of Addis Ababa: Implications for Sustainable Livelihoods of Returnees. Journal of Identity and Migration Studies, 17(1), 45–66.

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. SAGE publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

- Croitoru, A. (2020). Great Expectations: A Regional Study of Entrepreneurship Among Romanian Return Migrants. SAGE Open, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D., Duan, T., Hou, W., & Rees, W. (2015). Does Overseas Experience Matter? A study of returnee CEOs and IPOs of Chinese entrepreneurial firms. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2015(1), 10324. [CrossRef]

- Dai, O., & Liu, X. (2009). Returnee entrepreneurs and firm performance in Chinese high-technology industries. International Business Review, 18(4), 373–386.

- Danga, M., Chongela, J., & Kaudunde, I. (2019). Factors affecting the performance of rural small and medium enterprises (SMEs) a case study of Tanzania. International Journal of Academic Accounting, Finance & Management Research, 3(5), 35–47.

- Daniel, D. R. (1961). Management information crisis. Harvard Business Review, 111–121.

- Darnihamedani, P. (2016). Individual characteristics, contextual factors and entrepreneurial behavior.

- Darnihamedani, P., Block, J. H., Hessels, J., & Simonyan, A. (2018). Taxes, start-up costs, and innovative entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 355–369. [CrossRef]

- De Carolis, D., & Saparito, P. (2006). Social Capital, Cognition, and Entrepreneurial Opportunities: A Theoretical Framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30, 41–56. [CrossRef]

- De Haas, H. (2014). Migration theory: quo vadis? www.migrationdeterminants.eu.

- Dejen, E. Y., & Tadese, G. G. (2022). Acculturation experiences of Ethiopian migrant returnees while they were in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. African Journal of Social Work, 12(2), 50–58.

- Del Bosco, B., Mazzucchelli, A., Chierici, R., & Di Gregorio, A. (2021). Innovative startup creation: The effect of local factors and demographic characteristics of entrepreneurs. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(1), 145–164.

- Démurger, S., & Xu, H. (2011). Return Migrants: The Rise of New Entrepreneurs in Rural China. World Development, 39(10), 1847–1861. [CrossRef]

- Dessalegn, M., Nicol, A., & Debevec, L. (2020). From poverty to complexity?: the challenge of out-migration and development policy in Ethiopia.

- Dheer, R. J. S. (2018). Entrepreneurship by immigrants: a review of existing literature and directions for future research. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(3), 555–614. [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A., Hassan, R., Chhabra, M., Arrigo, E., & Palladino, R. (2022). Sustainable entrepreneurship impact and entrepreneurial venture life cycle: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 378, 134469.

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent and asymptotically normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 81, 10–23.

- Drori, I., Honig, B., & Wright, M. (2009). Transnational entrepreneurship: An emergent field of study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(5), 1001–1022.

- Estifanos, Y., & Zack, T. (2020). Migration barriers and migration momentum: Ethiopian irregular migrants in the Ethiopia-South Africa migration corridor. www.gdi.manchester.ac.uk.

- Fairlie, R. W., & Fossen, F. M. (2018). Opportunity versus necessity entrepreneurship: Two components of business creation.

- Filatotchev, I., Liu, X., Buck, T., & Wright, M. (2009). The export orientation and export performance of high-technology SMEs in emerging markets: The effects of knowledge transfer by returnee entrepreneurs. Journal of International Business Studies, 40, 1005–1021.

- Fong, R., Busch, N. B., Armour, M., Cook Heffron, L., & Chanmugan, A. (2007). Pathways to self-sufficiency: Successful entrepreneurship for refugees. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 16(1–2), 127–159. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Sage publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA.

- George, K. (2018). Factors influencing the performance of women entrepreneurs: A case of Iringa Municipality. Unpublished Master Thesis). Tanzania: Ruaha Catholic University.

- Goldin, C. (2016). Human Capital Human Capital. Social Economics, I, 235–287. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-349-19806-1_19.

- Goodman, L. A. (1961). Snowball Sampling. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 32(1), 148–170. [CrossRef]

- Gorostiaga, A., Aliri, J., Ulacia, I., Soroa, G., Balluerka, N., Aritzeta, A., & Muela, A. (2019). Assessment of entrepreneurial orientation in vocational training students: Development of a new scale and relationships with self-efficacy and personal initiative. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(MAY). [CrossRef]

- Gruenhagen, J. H. (2019). Returnee entrepreneurs and the institutional environment: case study insights from China. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 14(1), 207–230. [CrossRef]

- Gruenhagen, J. H., & Davidsson, P. (2018). Returnee entrepreneurs: Do they all boost emerging economies? International Review of Entrepreneurship, 16(4).

- Gupta, N., & Mirchandani, A. (2018). Investigating entrepreneurial success factors of women-owned SMEs in UAE. Management Decision, 56(1), 219–232.

- Habtamu, K., Desie, Y., Asnake, M., Lera, E. G., & Mequanint, T. (2021). Psychological distress among Ethiopian migrant returnees who were in quarantine in the context of COVID-19: institution-based cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Habtamu, K., Minaye, A., & Zeleke, W. A. (2017). Prevalence and associated factors of common mental disorders among Ethiopian migrant returnees from the Middle East and South Africa. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Hagos, S., Izak, M., & Scott, J. M. (2019). Objective institutionalized barriers and subjective performance factors of new migrant entrepreneurs. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(5), 842–858.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. In European Business Review (Vol. 31, Issue 1, pp. 2–24). Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Hajizadeh, A., & Zali, M. (2016). Prior knowledge, cognitive characteristics and opportunity recognition. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 22(1), 63–83.

- Hashemi, N., Marzban, M., Sebar, B., & Harris, N. (2019). Acculturation and psychological well-being among Middle Eastern migrants in Australia: The mediating role of social support and perceived discrimination. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 72, 45–60.

- Henrik, J., & Gruenhagen, J. H. (2021). Returnee Entrepreneurship : How Home-Country Institutions, Estrangement and Support Influence Entrepreneurial Intentions. 0–34.

- Henseler, J. (2018). Partial least squares path modeling: Quo vadis? Quality and Quantity, 52(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424.

- Hu, W., Xu, Y., Zhao, F., & Chen, Y. (2022). Entrepreneurial Passion and Entrepreneurial Success — The Role of Psychological Capital and Entrepreneurial Policy Support. 13(February), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Huang, Y., Huang, R., Xie, G., & Cai, W. (2022). Factors Influencing Returning Migrants’ Entrepreneurship Intentions for Rural E-Commerce: An Empirical Investigation in China. [CrossRef]

- Jony, A. I., & Serradell-López, E. (2021). A pls-sem approach in evaluating a virtual teamwork model in online higher education: why and how? Research and Innovation Forum 2020: Disruptive Technologies in Times of Change, 217–232.

- Kamunge, M. S., & Tirimba, O. I. (2014). Factors Affecting the Performance of Small and Micro Enterprises in Limuru Town Market of Kiambu County, Kenya. 4(12).

- anapathipillai, K., & Azam, S. M. F. (2019). Women entrepreneurs path to success: An investigation of the critical success factors in Malaysia. European Journal of Human Resource Management Studies.

- Kenney, M., Breznitz, D., & Murphree, M. (2013). Coming back home after the sun rises: Returnee entrepreneurs and growth of high tech industries. Research Policy, 42(2), 391–407. [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, V. K., & Ferguson, J. R. (1999). Critical success factors (CSFs) and the growth of IT in selected geographic regions. Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences. 1999. HICSS-32. Abstracts and CD-ROM of Full Papers, 13-pp.

- Kim, D., & Lee, S. Y. (2022). When venture capitalists are attracted by the experienced. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 31.

- Kline, R. B. (1998). Structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford, 33.

- Kock, N., & Hadaya, P. (2018). Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Information Systems Journal, 28(1), 227–261.

- Levie, J., & Autio, E. (2008). A theoretical grounding and test of the GEM model. Small Business Economics, 31, 235–263.

- Lin, D., Lu, J., Liu, X., & Zhang, X. (2016a). International knowledge brokerage and returnees’ entrepreneurial decisions. Journal of International Business Studies, 47, 295–318.

- Lin, D., Lu, J., Liu, X., & Zhang, X. (2016b). International knowledge brokerage and returnees’ entrepreneurial decisions. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(3), 295–318. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X., & Tao, S. (2012). Transnational entrepreneurs: Characteristics, drivers, and success factors. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 10, 50–69.

- Liu, X., Wright, M., & Filatotchev, I. (2015). Learning, firm age and performance: An investigation of returnee entrepreneurs in Chinese high-tech industries. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 33(5), 467–487. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Almor, T. (2016). How culture influences the way entrepreneurs deal with uncertainty in inter-organizational relationships: The case of returnee versus local entrepreneurs in China. International Business Review, 25(1), 4–14. [CrossRef]

- Ma, H., Barbe, F. T., & Zhang, Y. C. (2018). Can social capital and psychological capital improve the entrepreneurial performance of the new generation of migrantworkers in China? Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(11), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. (2002). Social-capital mobilization and income returns to entrepreneurship: The case of return migration in rural China. Environment and Planning A, 34(10), 1763–1784. [CrossRef]

- Macková, L., & Harmáček, J. (2019). The Motivations and Reality of Return Migration to Armenia. Central and Eastern European Migration Review, 8(2), 145–160. [CrossRef]

- Malebana, M. J., & Mahlaole, S. T. (2023). Prior entrepreneurship exposure and work experience as determinants of entrepreneurial intentions among South African university of technology students. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1176065.

- Maria Hagan, J., & Wassink, J. (2016). New Skills, New Jobs: Return Migration, Skill Transfers, and Business Formation in Mexico. Social Problems, 63(4), 513–533. [CrossRef]

- Minniti, M. (2008). E T & P The Role of. 1, 779–790.

- Mohamed, M. A., Abdul-Talib, A. N., & Ramlee, A. A. (2022). Determinants of the firm performance of returnee entrepreneurs in Somalia: the effects of external environmental conditions. Journal of Enterprising Communities, 16(6), 1060–1082. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S., Singh, S., & Gupta, H. (2023). Assessing enablers of green entrepreneurship in circular economy: An integrated approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 388, 135999.

- Motoyama, Y., & Knowlton, K. (2016). From resource munificence to ecosystem integration: The case of government sponsorship in St. Louis. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 28(5–6), 448–470.

- Muhamad, S., Rashid, N. K. A., Hussain, N. E., Akhir, N. H. M., & Ahmat, N. (2020). Resilience as a moderator of government and family support in explaining entrepreneurial interest and readiness among single mothers. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 13, e00157.

- Naudé, W., Siegel, M., & Marchand, K. (2017). Migration, entrepreneurship and development: critical questions. [CrossRef]

- Neal, D., & Rosen, S. (2000). Theories of the distribution of labor earnings. In Handbook of Income Distribution (Vol. 1, pp. 379–427). http://www.nber.org/papers/w6378.

- Nicol, A., Abdoubaetova, A., Wolters, A., Kharel, A., Murzakolova, A., Gebreyesus, A., Lucasenco, E., Chen, F., Sugden, F., Sterly, H., Kuznetsova, I., Masotti, M., Vittuari, M., Dessalegn, M., Aderghal, M., Phalkey, N., Sakdapolrak, P., Mollinga, P., & Mogilevskii, R. (2020). Between a rock and a hard place: early experience of migration challenges under the Covid-19 pandemic. IWMI Working Papers, 2020(195), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modelling, Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. In Industrial Management and Data Systems (Vol. 116, Issue 9). [CrossRef]

- Nkonoki, E., & Ericsson, H. (2010). What are the factors limiting the success and/or growth of small businesses in Tanzania? – An empirical study on small business growth. Arcada University of Applied Sciences International Business.

- Oakland, G. B. (1953). Determining Sample Size. The Canadian Entomologist, 85(3), 108–113. [CrossRef]

- Padiaychee, T. (2016). Access to finance : The disconnect between entrepreneurs and financiers. University of Pretoria, January.

- Paper, W. (2017). Return Migration and Entrepreneurial Success : An Empirical Analysis for Egypt. 98.

- Payne, G., & Payne, J. (2004). Key concepts in social research.

- Penrose, E. T. (2009). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Oxford university press.

- Popkova, E. G., & Sergi, B. S. (2020). Human capital and AI in industry 4.0. Convergence and divergence in social entrepreneurship in Russia. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 21(4), 565–581.

- Portes, A. (2009). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Knowledge and Social Capital, 43–67.

- Pruthi, S. (2014). Social ties and venture creation by returnee entrepreneurs. International Business Review, 23(6), 1139–1152. [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, A. (2021). Partial least squares structural squation modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis for social and management research: a literature review. Journal of Industrial Engineering & Management Research.

- Putnam, R. D. (1993). The prosperous community. The American Prospect, 4(13), 35–42.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. In Culture and politics: A reader (pp. 223–234). Springer.

- Qin, F., Wright, M., & Gao, J. (2017). Are ‘sea turtles’ slower? Returnee entrepreneurs, venture resources and speed of entrepreneurial entry. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(6), 694–706. [CrossRef]

- Quarterly Economic Profile. (2021). November.

- Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G. T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 761–787.

- Riaño, Y. (2023). Migrant Entrepreneurs as Agents of Development ? Geopolitical Context and Transmobility Strategies of Colombian Migrants Returning from Venezuela. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 24, 539–562. [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Mitchell, R., & Gudergan, S. P. (2020). Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(12), 1617–1643.

- Rosado-Pinto, F., & Loureiro, S. M. C. (2020). The growing complexity of customer engagement: a systematic review. EuroMed Journal of Business, 15(2), 167–203.

- Scott, W. R. (1999). A Call for Two-Way Traffic: Improving the Connection Between Social Movement and Organizational/Institutional Theory.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. john wiley & sons.

- Shakeel, M., Yaokuang, L., & Gohar, A. (2020). Identifying the Entrepreneurial Success Factors and the Performance of Women-Owned Businesses in Pakistan : The Moderating Role of National Culture. [CrossRef]

- Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226.

- Sharma, P. N., Liengaard, B. D., Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2022). Predictive model assessment and selection in composite-based modeling using PLS-SEM: extensions and guidelines for using CVPAT. European Journal of Marketing, ahead-of-print.

- Sharma, P. N., Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N., & Ray, S. (2021). Prediction-oriented model selection in partial least squares path modeling. Decision Sciences, 52(3), 567–607.

- Shi, W., & Weber, M. (2021). The impact of entrepreneurs’ prior experience and communication networks on perceived knowledge access. Journal of Knowledge Management, 25(5), 1406–1426.

- Smallbone, D., & Welter, F. (2012). Entrepreneurship and institutional change in transition economies: The Commonwealth of Independent States, Central and Eastern Europe and China compared. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(3–4), 215–233.

- Soomro, B. A., Abdelwahed, N. A. A., & Shah, N. (2019). The influence of demographic factors on the business success of entrepreneurs: An empirical study from the small and Medium-Sized Enterprises context of Pakistan. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 23(2).

- Stuart, T. E., & Sorenson, O. (2005). Social networks and entrepreneurship. Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 233–252.