Submitted:

28 July 2024

Posted:

30 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample

- -

- Sex: Male and Female

- -

- Age: subjects aged between 18 and 24 years.

- -

- Studies: students enrolled in undergraduate studies.

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Internal Structure of the Instrument

3.3. Level of Procrastination as Perceived by Students

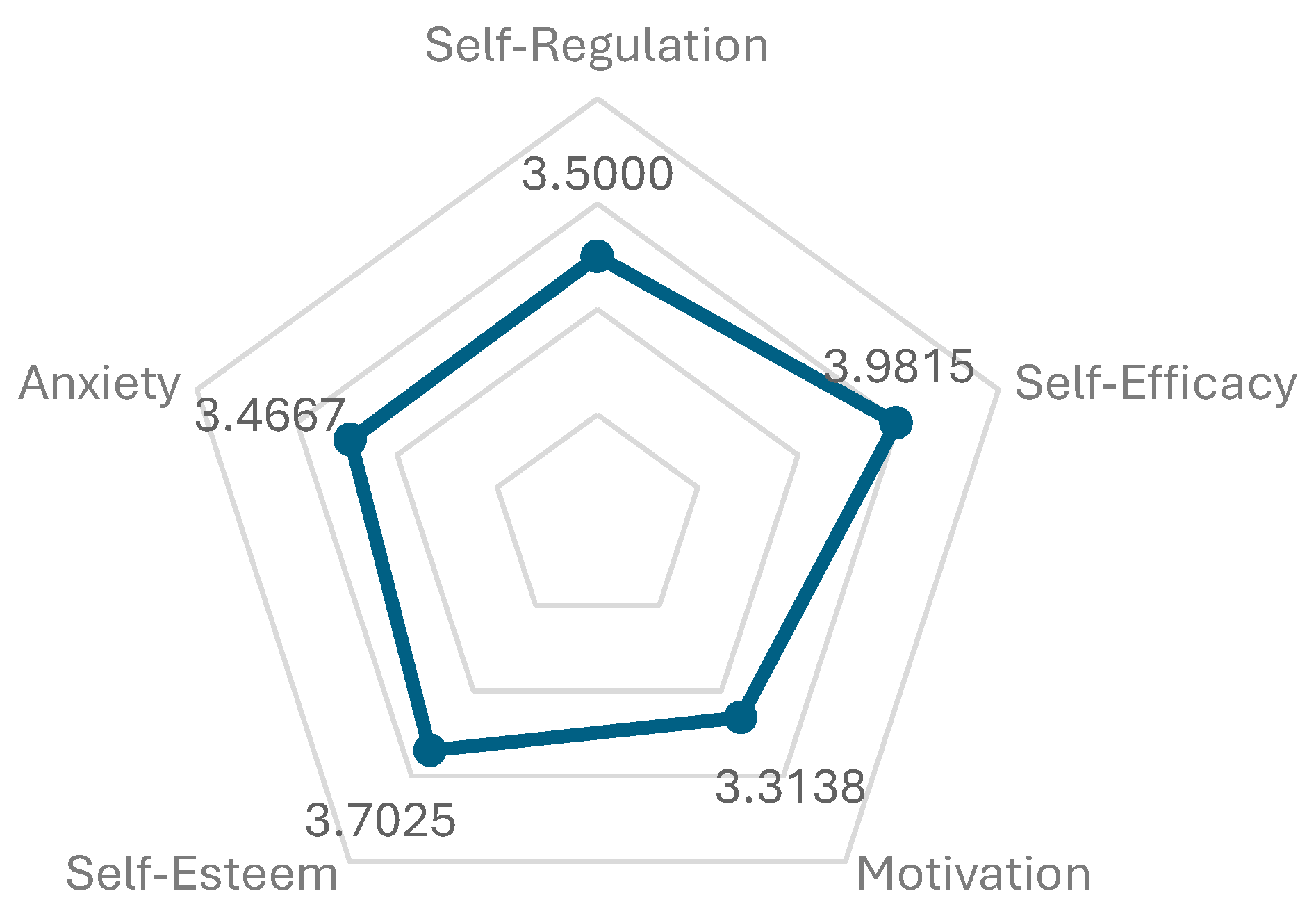

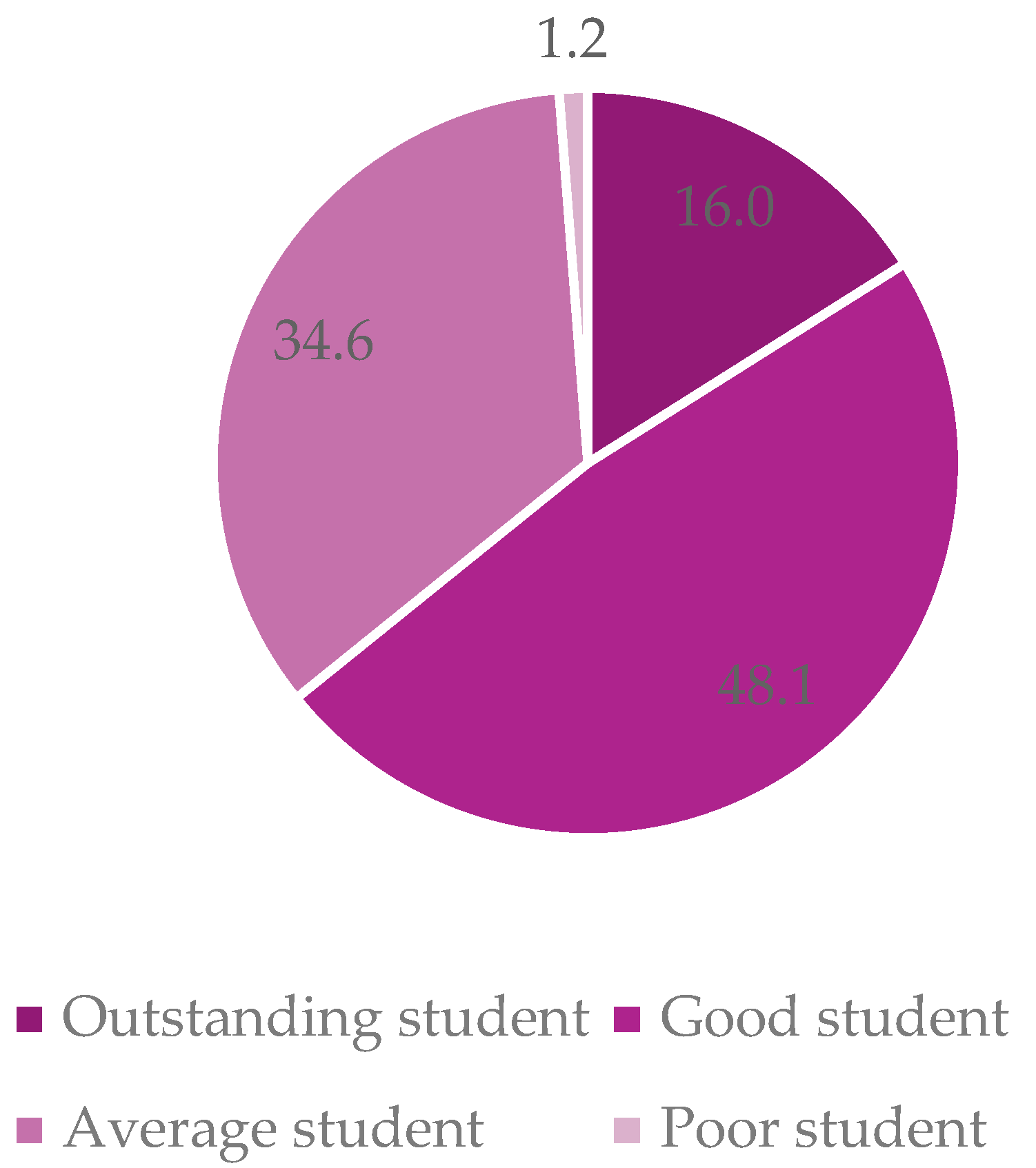

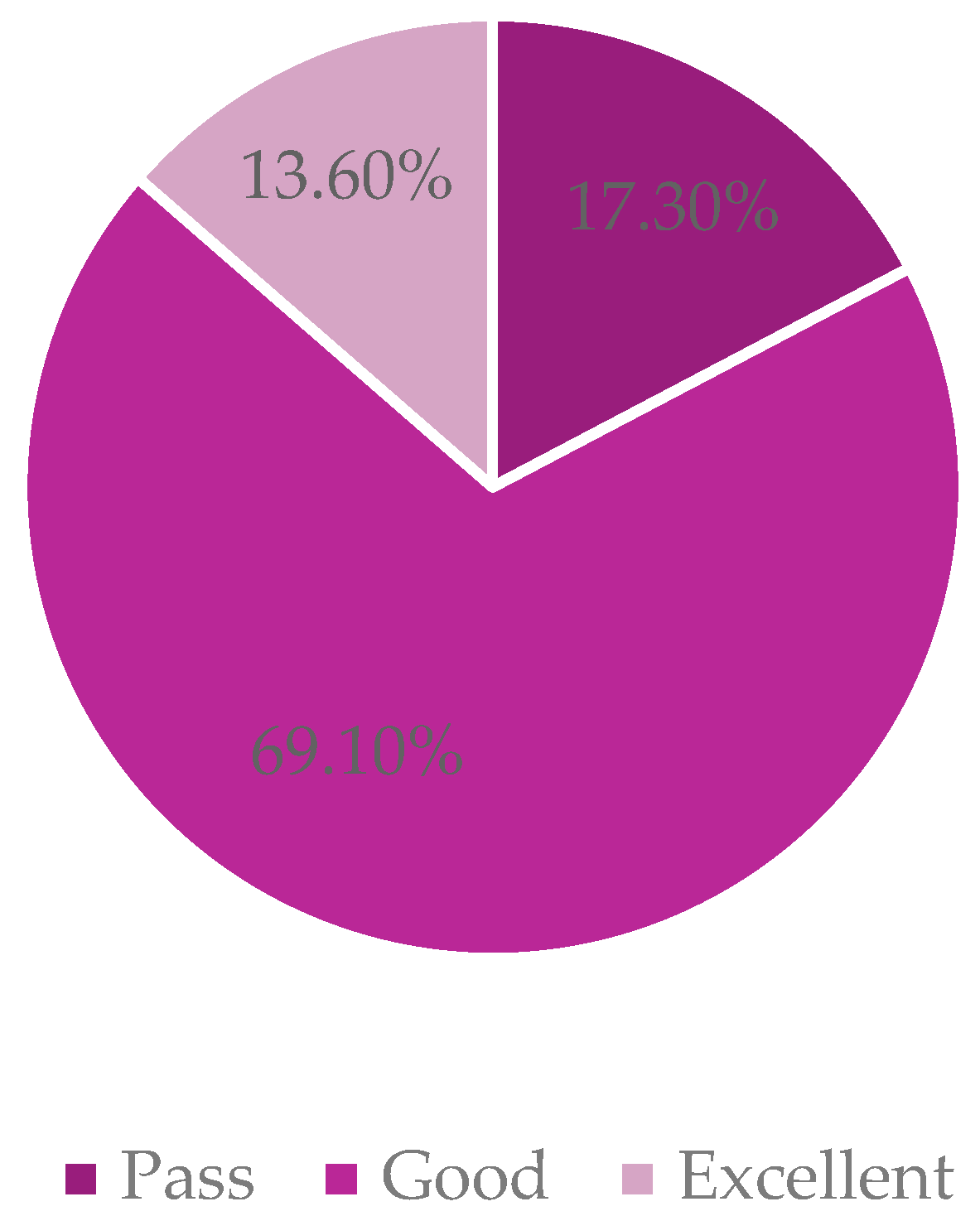

3.4. Perceived Academic Performance

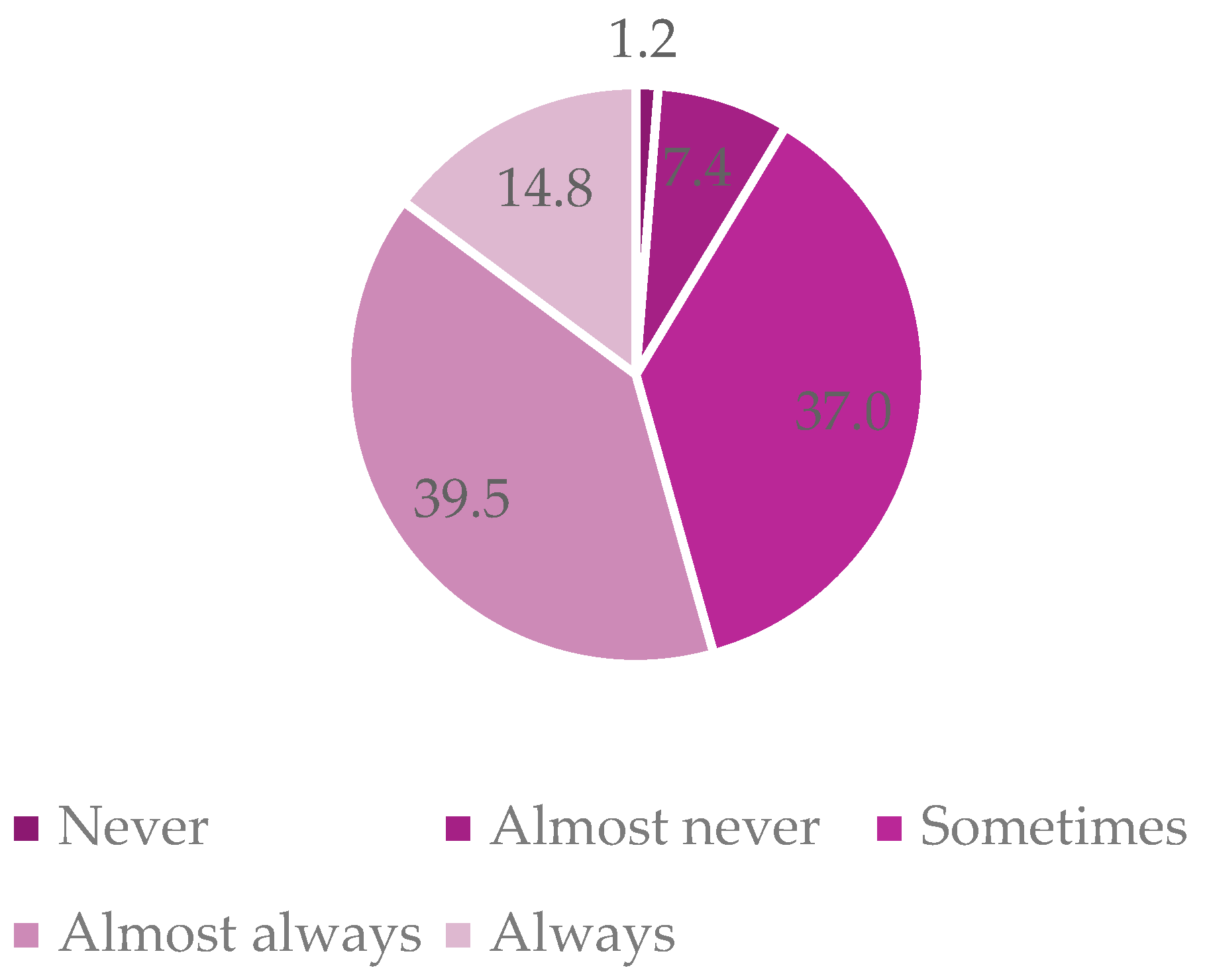

3.5. Screen Usage Habits of Students

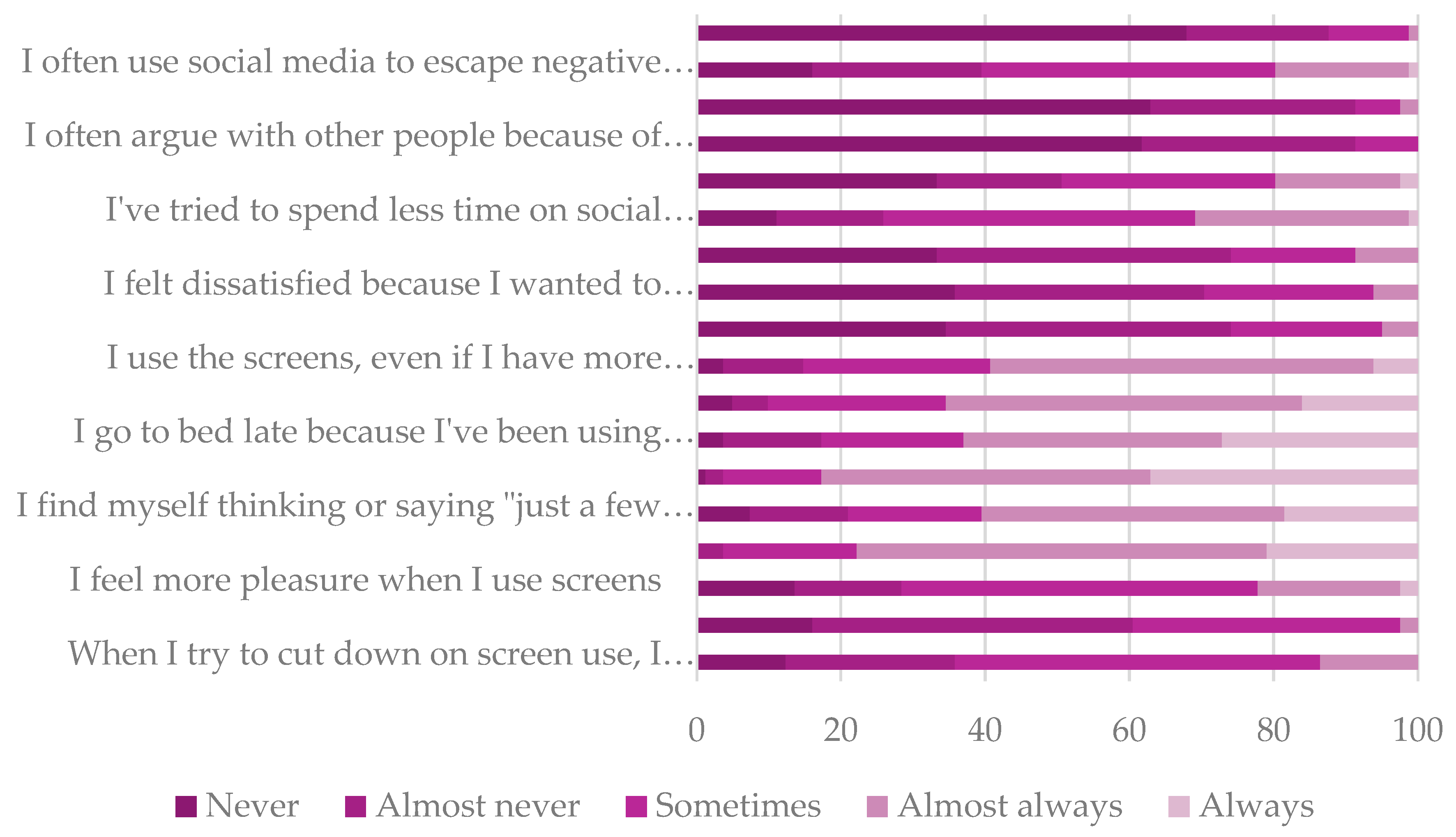

3.6. Relationship between Screen Use and Academic Procrastination According to Its Dimensions

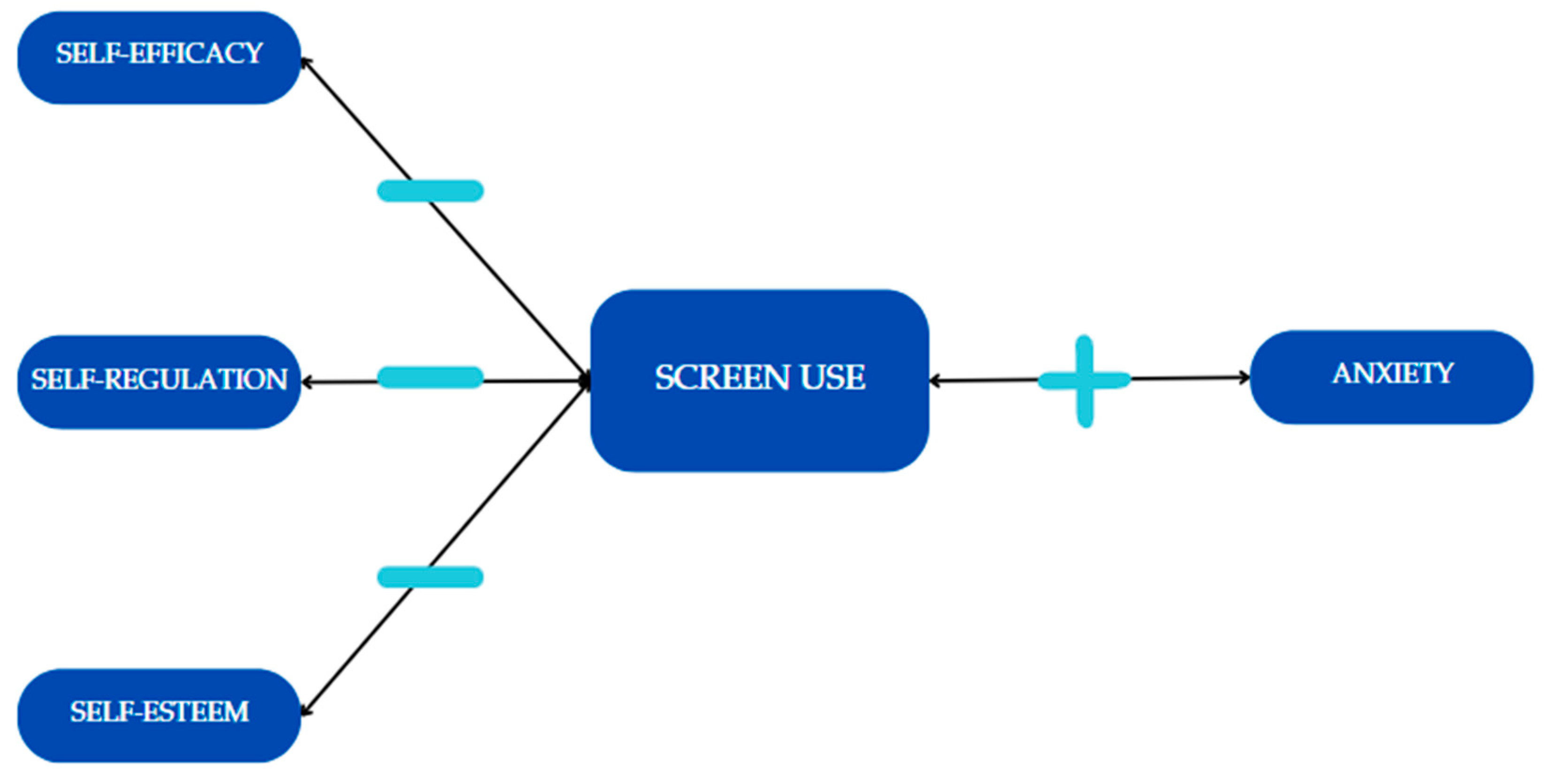

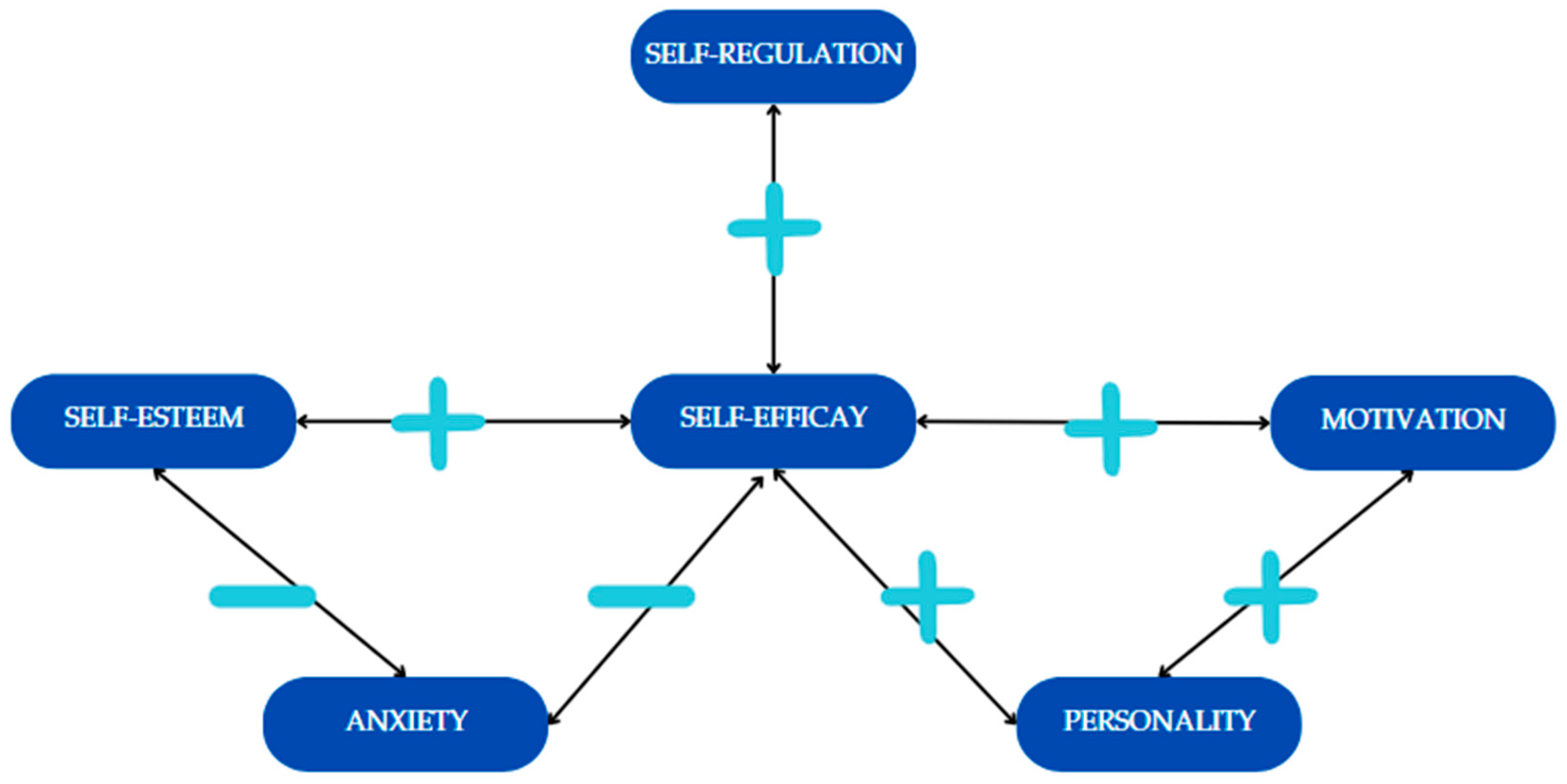

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Behr, A.; Giese, M.; Teguim Kamdjou, H.D.; Theune, K. Dropping out of University: A Literature Review. Review of Education 2020, 8, 614–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahu, E.R.; Nelson, K. Student Engagement in the Educational Interface: Understanding the Mechanisms of Student Success. Higher Education Research & Development 2018, 37, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odlin, D.; Benson-Rea, M.; Sullivan-Taylor, B. Student Internships and Work Placements: Approaches to Risk Management in Higher Education. High Educ (Dordr) 2022, 83, 1409–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, M.A.; Lashari, A.A.; Abbas, S. Analysis of Sustainable Academic Performance through Interactive Learning Environment in Higher Education. Global Economics Review 2023, VIII, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, Á.; Molnár, G. Factors Influencing Academic Performance and Dropout Rates in Higher Education. Oxf Rev Educ 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu Alves, S.; Sinval, J.; Lucas Neto, L.; Marôco, J.; Gonçalves Ferreira, A.; Oliveira, P. Burnout and Dropout Intention in Medical Students: The Protective Role of Academic Engagement. BMC Med Educ 2022, 22, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas-Caravaca, E.; Sánchez-Romero, E.I.; Antón-Ruiz, J.A. Academic Burnout, Personality, and Academic Variables in University Students. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ 2024, 14, 1561–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Satele, D.; West, C.P. Association of Characteristics of the Learning Environment and US Medical Student Burnout, Empathy, and Career Regret. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e2119110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Xu, H.; Feng, J.; Ye, J.; Lu, Z.; Gan, Y. The Global Prevalence of Burnout among General Practitioners: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Fam Pract 2022, 39, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, T.; Kadhum, M.; Farrell, S.M.; Ventriglio, A.; Molodynski, A. A Descriptive Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing among Medical Students in Portugal. International Review of Psychiatry 2019, 31, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorilli, C.; De Stasio, S.; Di Chiacchio, C.; Pepe, A.; Salmela-Aro, K. School Burnout, Depressive Symptoms and Engagement: Their Combined Effect on Student Achievement. Int J Educ Res 2017, 84, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, M.; Abbasi, E.; Khoshnodifar, Z. Students’ Academic Burnout in Iranian Agricultural Higher Education System: The Mediating Role of Achievement Motivation. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.Y.; Hancock, J.T. Social Media Mindsets: A New Approach to Understanding Social Media Use and Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Joiner, T.E.; Rogers, M.L.; Martin, G.N. Increases in Depressive Symptoms, Suicide-Related Outcomes, and Suicide Rates Among U.S. Adolescents After 2010 and Links to Increased New Media Screen Time. Clinical Psychological Science 2018, 6, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Cosci, F.; Mansueto, G.; Margraf, J. The Relationship between Social Media Use, Stress Symptoms and Burden Caused by Coronavirus (Covid-19) in Germany and Italy: A Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Investigation. J Affect Disord Rep 2021, 3, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marco, C.; Chóliz, M. Tratamiento Cognitivo – Conductual En Un Caso de Adicción a Internet y Videojuegos. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy 2013, 13, 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Bolaños, S.; Mahamud Rodríguez, K. Procrastinación Académica y Adicción a Internet En Estudiantes Universitarios de Lima Metropolitana. Avances en Psicología 2017, 25, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruzado, L.; Matos, L.; Kendall, R. Adicción a Internet: Perfil clínico y epidemiológico de pacientes hospitalizados en un instituto nacional de salud mental. Revista Médica Herediana 2006, 17, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Guzmán, R.; Cisneros-Chavez, B. Adicción a Redes Sociales y Procrastinación Académica En Estudiantes Universitarios. Nuevas Ideas en Informática Educativa 2019, 15, 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hayat, A.A.; Kojuri, J.; Mitra Amini, M.D. Academic Procrastination of Medical Students: The Role of Internet Addiction. J Adv Med Educ Prof 2020, 8, 83. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei-Gazki, P.; Ilaghi, M.; Masoumian, N. The Triangle of Anxiety, Perfectionism, and Academic Procrastination: Exploring the Correlates in Medical and Dental Students. BMC Med Educ 2024, 24, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amarnath, A.; Ozmen, S.; Struijs, S.Y.; de Wit, L.; Cuijpers, P. Effectiveness of a Guided Internet-Based Intervention for Procrastination among University Students – A Randomized Controlled Trial Study Protocol. Internet Interv 2023, 32, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutel, M.E.; Klein, E.M.; Aufenanger, S.; Brähler, E.; Dreier, M.; Müller, K.W.; Quiring, O.; Reinecke, L.; Schmutzer, G.; Stark, B.; et al. Procrastination, Distress and Life Satisfaction across the Age Range – A German Representative Community Study. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0148054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingsieck, K.B.; Grund, A.; Schmid, S.; Fries, S. Why Students Procrastinate: A Qualitative Approach. J Coll Stud Dev 2013, 54, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, P. The Nature of Procrastination: A Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review of Quintessential Self-Regulatory Failure. Psychol Bull 2007, 133, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala Ramírez, A.S.; Rodríguez Diaz, R.Y.; Villanueva Quispe, W.; Hernández Garcia, M.; Campos Ramirez, M. La Procrastinación Académica: Teorías, Elementos y Modelos. Revista Muro de la Investigación 2020, 5, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Correia, R.; Jácome de Moura, P. Aprendizagem e Procrastinação: Uma Revisão de Publicações No Período 2005-2015. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geara, G.B.; Teixeira, M.A.P. Questionário de Procrastinação Acadêmica – Consequências Negativas: Propriedades Psicométricas e Evidências de Validade. Revista Avaliação Psicológica 2017, 16, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, P.; Klingsieck, K.B. Academic Procrastination: Psychological Antecedents Revisited. Aust Psychol 2016, 51, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonka, K.; Chow, A.; Keskinen, J.; Hakkarainen, K.; Sandström, N.; Pyhältö, K. How to Measure PhD Students’ Conceptions of Academic Writing – and Are They Related to Well-Being? J Writ Res 2014, 5, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.d.C.; Ramos, F.P. PROCRASTINAÇÃO ACADÊMICA EM ESTUDANTES UNIVERSITÁRIOS: UMA REVISÃO SISTEMÁTICA DA LITERATURA. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional 2021, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, S.A.; Villegas, G.; Centeno, S.B. Procrastinación académica: Validión de una escala en una muestra de estudiantes de una univerisada privada. Liberabit : Revista de Psicología 2014, 20, 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Moreta Herrera, R.; Durán Rodríguez, T.; Villegas Villacrés, N. Regulación Emocional y Rendimiento Como Predictores de La Procrastinación Académica En Estudiantes Universitarios. Revista de Psicología y Educación - Journal of Psychology and Education 2018, 13, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hen, M.; Goroshit, M. The Effects of Decisional and Academic Procrastination on Students’ Feelings toward Academic Procrastination. Current Psychology 2020, 39, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Kou, Z.; Du, Y.; Wang, K.; Xu, Y. Academic Procrastination and Negative Emotions Among Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating and Buffering Effects of Online-Shopping Addiction. Front Psychol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salguero-Pazos, M.R.; Reyes-de-Cózar, S. Interventions to Reduce Academic Procrastination: A Systematic Review. Int J Educ Res 2023, 121, 102228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.d.C.; Ramos, F.P. PROCRASTINAÇÃO ACADÊMICA EM ESTUDANTES UNIVERSITÁRIOS: UMA REVISÃO SISTEMÁTICA DA LITERATURA. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional 2021, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, C.A.; Won, S.; Hussain, M. Examining the Relations of Time Management and Procrastination within a Model of Self-Regulated Learning. Metacogn Learn 2017, 12, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, M.L.; Liu, L.; Yuan, W. The Relationship between Learning Efficacy, Personality Traits and Scholastic Attainment of Undergraduates. Journal of Hubei Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences) 2015, 35, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Ran, G.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, T. A Meta-Analysis of Self-Efficacy and Mental Health in the Context of China. Psychological Development and Education 2019, 35, 759–769. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T. The Influences of the Big Five Personality Traits on Academic Achievements: Chain Mediating Effect Based on Major Identity and Self-Efficacy. Front Psychol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y. Relationship between Personality Traits and Learning Burnout among Undergraduates: Mediating Effect of General Procrastination. International Journal of Arts and Social Science 2024, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.M.; Li, C.M.; Ruan, M.E. Relationship between Academic Self-Efficacy and Academic Burnout among College Students: Mediating Effect of General Procrastination. Global Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences 2024, 4, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, W.Y.; et al. Learning Burnout Status of College Students and Its Relationship with Personality Character. China Journal of Health Psychology 2012, 20, 1411–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.J.; Jin, C.C. Relationship between Mobile Phone Dependence and Learning Burnout among College Students: Moderating Effect of Personality. Chinese Journal of Special Education 2018, 5, 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Trigueros, R.; Padilla, A.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Lirola, M.J.; García-Luengo, A.V.; Rocamora-Pérez, P.; López-Liria, R. The Influence of Teachers on Motivation and Academic Stress and Their Effect on the Learning Strategies of University Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J.C.; Watson, A.A. Coping Self-Efficacy and Academic Stress Among Hispanic First-Year College Students: The Moderating Role of Emotional Intelligence. Journal of College Counseling 2016, 19, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saplavska, J.; Jerkunkova, A. Academic Procrastination and Anxiety among Students.; May 23 2018.

- Ferrari, J.R.; Johnson, J.L.; McCown, W.G. Procrastination and Task Avoidance: Theory, Research, and Treatment. Springer Science & Business Media 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Parwez, S.; Khurshid, S.; Yousaf, I. Impact of Procrastination on Self-Esteem of College and University Students of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Multicultural Education 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.; Pandit, U.; Nerurkar, A.; Verma, C.; Gandhi, S. Test Anxiety and Procrastination in Physiotherapy Students. J Educ Health Promot 2021, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasempour, S.; Babaei, A.; Nouri, S.; Basirinezhad, M.H.; Abbasi, A. Relationship between Academic Procrastination, Self-Esteem, and Moral Intelligence among Medical Sciences Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychol 2024, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duru, E.; Balkis, M. Procrastination, Self-Esteem, Academic Performance, and Well-Being: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Educational Psychology 2017, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, R.-D.; Ding, Y.; Hong, W.; Jiang, S. The Relations between Academic Procrastination and Self-Esteem in Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study. Current Psychology 2023, 42, 7534–7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, P.; Chandra, K.; Vanishree, M.; Amritha, N. Relationship between Academic Procrastination and Self-Esteem among Dental Students in Bengaluru City. Journal of Indian Association of Public Health Dentistry 2019, 17, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G.J.; Moreno, O. Ansiedad y Autoestima: Su Relación Con El Uso de Redes Sociales En Adolescentes Mexicanos. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala 2019, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Kemal, F.; Riniati, W.O.; Haetami, A.; Wahab, A.; Pratiwi, E.Y.R. The Analysis of Relationship between Learning Motivation and Student Procrastination Behavior in Public Elementary School. Journal on Education 2023, 5, 7710–7714. [Google Scholar]

- Anggoro, A. The Relationship between Academic Procrastination and Stress Level of Medical Students. Scientia Psychiatrica 2021, 4, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, J.H.; Mahmood, N. Development and Validation of an Academic Self-Regulation Scale for University Students. Journal of Behavioural Sciences 2013, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Tapia, J.; Panadero Calderón, E.; Díaz Ruiz, M.A. Development and Validity of the Emotion and Motivation Self-Regulation Questionnaire (EMSR-Q). Span J Psychol 2014, 17, E55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowbotham, M.; Schmitz, G.S. Development and Validation of a Student Self-Efficacy Scale. Journal of Nursing & Care 2013, 02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Pelletier, L.G.; Blais, M.R.; Briere, N.M.; Senecal, C.; Vallieres, E.F. The Academic Motivation Scale: A Measure of Intrinsic, Extrinsic, and Amotivation in Education. Educ Psychol Meas 1992, 52, 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. J Relig Health 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, L.R.; Johnson, J.A.; Eber, H.W.; Hogan, R.; Ashton, M.C.; Cloninger, C.R.; Gough, H.G. The International Personality Item Pool and the Future of Public-Domain Personality Measures. J Res Pers 2006, 40, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Deane, F.P. Development of a Short Form of the Test Anxiety Inventory (TAI). J Gen Psychol 2002, 129, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Self-Evaluation Questionnaire). 1970.

- Hunter, S.C.; Houghton, S.; Zadow, C.; Rosenberg, M.; Wood, L.; Shilton, T.; Lawrence, D. Development of the Adolescent Preoccupation with Screens Scale. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Lemmens, J.S.; Valkenburg, P.M. The Social Media Disorder Scale. Comput Human Behav 2016, 61, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galve-González, C.; Bernardo, A.B.; Castro-López, A. Understanding the Dynamics of College Transitions between Courses: Uncertainty Associated with the Decision to Drop out Studies among First and Second Year Students. European Journal of Psychology of Education 2024, 39, 959–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truta, C.; Parv, L.; Topala, I. Academic Engagement and Intention to Drop Out: Levers for Sustainability in Higher Education. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcheglova, I.; Gorbunova, E.; Chirikov, I. The Role of the First-Year Experience in Student Attrition. Quality in Higher Education 2020, 26, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Fernández, S.; Faure-Carvallo, A.; Calderon, C.; Gustems, J. Procrastination Among University Students: A Study Investigating Sociodemographic and Psychological Factors. International Journal of Instruction 2024, 17, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kljajic, K.; Gaudreau, P. Does It Matter If Students Procrastinate More in Some Courses than in Others? A Multilevel Perspective on Procrastination and Academic Achievement. Learn Instr 2018, 58, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santyasa, I.W.; Rapi, N.K.; Sara, I.W.W. Project Based Learning and Academic Procrastination of Students in Learning Physics. International Journal of Instruction 2020, 13, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Lee, Y.S. The Effects of Medical Students’ Self-Oriented Perfectionism on Academic Procrastination: The Mediating Effect of Fear of Failure. Korean J Med Educ 2022, 34, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olea, M.T.; Olea, A.N. Perceptiveness and Sense Impression of Procrastination across Correlates. International Research Journal of Social Sciences 2015, 4, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A.; Knaus, W.J. Overcoming Procrastination; Signet Books: New York, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Azzaakiyyah, H.K. The Impact of Social Media Use on Social Interaction in Contemporary Society. Technology and Society Perspectives (TACIT) 2023, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar Díaz, I.; Kopecký, K.; Romero Rodríguez, J.M.; Cáceres Reche, M.P.; Trujillo Torres, J.M. Patologías Asociadas al Uso Problemático de Internet. Una Revisión Sistemática y Metaanálisis En WOS y Scopus. Investigación Bibliotecológica: archivonomía, bibliotecología e información 2020, 34, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Teo, E.W.; Yan, T. The Impact of Smartphone Addiction on Chinese University Students’ Physical Activity: Exploring the Role of Motivation and Self-Efficacy. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2022, 15, 2273–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.-C.; Yang, T.-A.; Lee, J.-C. The Relationship between Smartphone Addiction, Parent–Child Relationship, Loneliness and Self-Efficacy among Senior High School Students in Taiwan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, L.; Loureiro, M.; Pereira, H.; Monteiro, S.; Marina Afonso, R.; Esgalhado, G. Relationship Between Internet Addiction and Self-Esteem: Cross-Cultural Study in Portugal and Brazil. Interact Comput 2017, 29, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subiyakto, D.M.; Saktini, F.; Sumekar, T.A. The Relationship Between Social Media Addiction and Self-Esteem in Medical Students of Diponegoro University. Jurnal Kedokteran Diponegoro (Diponegoro Medical Journal) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favieri, F.; Forte, G.; Savastano, M.; Casagrande, M. Validation of the Brief Screening of Social Network Addiction Risk. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2024, 247, 104323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Teng, Z.; Wei, Z.; Jin, K.; Xiao, J.; Tang, H.; Wu, H.; Yang, Y.; Yan, H.; Chen, J.; et al. Internet Addiction among Teenagers in a Chinese Population: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Its Relationship with Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms. J Psychiatr Res 2022, 153, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, E.; Morin, A.J.S.; Tardif-Grenier, K.; Archambault, I.; Dupéré, V.; Hébert, C. Profiles of Anxious and Depressive Symptoms Among Adolescent Boys and Girls: Associations with Coping Strategies. J Youth Adolesc 2022, 51, 570–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabrina, R.; Risnawati, R.; Anwar, K.; Hulawa, D.E.; Sabti, F.; Rijan, M.H.B.M.; Kakoh, N.A. The Relation between Self-Regulation, Self-Efficacy and Achievement Motivation among Muslim Students in Senior High Schools. International Journal of Islamic Studies Higher Education 2023, 2, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanah, S.I.; Tafrilyanto, C.F.; Aini, Y. Mathematical Reasoning: The Characteristics of Students’ Mathematical Abilities in Problem Solving. J Phys Conf Ser 2019, 1188, 012057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska-Gieracha, J.; Mazurek, J. The Role of Self-Efficacy in the Recovery Process of Stroke Survivors. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2020, 13, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usán Supervía, P.; Salavera Bordás, C.; Juarros Basterretxea, J.; Latorre Cosculluela, C. Influence of Psychological Variables in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem in the Relationship between Self-Efficacy and Satisfaction with Life in Senior High School Students. Soc Sci 2023, 12, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Cheng, H. The <scp>Big-Five</Scp> Personality Factors, Cognitive Ability, Health, and Social-demographic Indicators as Independent Predictors of Self-efficacy: A Longitudinal Study. Scand J Psychol 2024, 65, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousset, E.S.-P.; Lane, J.; Therriault, D.; Roberge, P. Association between Self-Efficacy and Anxiety Symptoms in Adolescents: Secondary Analysis of a Preventive Program. Social and Emotional Learning: Research, Practice, and Policy 2024, 3, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roick, J.; Ringeisen, T. Self-Efficacy, Test Anxiety, and Academic Success: A Longitudinal Validation. Int J Educ Res 2017, 83, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armum, P.; Chellappan, K. Social and Emotional Self-Efficacy of Adolescents: Measured and Analysed Interdependencies within and across Academic Achievement Level. Int J Adolesc Youth 2016, 21, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, C.S.R. Self-Esteem, Coping Strategies, and Anxiety Among Generation Z: A Correlational Study. Global Research Journal of Social Sciences and Management 2024, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, M. The Influence of MBTI Personality Types on College Students’ Academic Performance: The Mediating Role of Learning Motivation. Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences 2024, 29, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | Nº item | α-Cronbach |

|---|---|---|

| Screen Use | 18 | 0,886 |

| Self-Regulation | 10 | 0,774 |

| Self-Efficacy | 10 | 0,859 |

| Motivation | 12 | 0,824 |

| Self-Esteem | 10 | 0,856 |

| Personality | 10 | 0,545 |

| Anxiety | 10 | 0,831 |

| Total (n=81) | 80 | 0,795 |

| Dimensions | N | Minimun | Maximun | Mean | Standard dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Regulation | 81 | 2,30 | 4,60 | 3,5000 | ,56236 |

| Self-Efficacy | 81 | 2,40 | 5,00 | 3,9815 | ,53528 |

| Motivation | 81 | 2,33 | 4,17 | 3,3138 | ,46084 |

| Self-Esteem | 81 | 2,30 | 4,90 | 3,7025 | ,59033 |

| Anxiety | 81 | 1,60 | 4,90 | 3,4667 | ,70338 |

| 1= Never, 2 = Almost never, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Almost always, 5 = Always | |||||

| Dimension | N | Minimun | Maximun | Mean | Standard dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screen Use | 81 | 1,22 | 3,67 | 2,6968 | ,53835 |

| 1= Never, 2 = Almost never, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Almost always, 5 = Always | |||||

| SELF-ESTEEM | SELF-REGULATION | SELF-EFFICACY | MOTIVATION | ANXIETY | PERSONALITY | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCREEN USE | Pearson correlation | -,402** | -,359** | -,307** | -,124 | ,361** | ,096 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | ,000 | ,001 | ,005 | ,268 | ,001 | ,391 | |

| SELF-ESTEEM | Pearson correlation | 1 | ,186 | ,407** | ,131 | -,507** | ,079 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | ,097 | ,000 | ,243 | ,000 | ,483 | ||

| SELF-REGULATION | Pearson correlation | 1 | ,376** | ,190 | -,148 | ,168 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | ,001 | ,089 | ,189 | ,134 | |||

| SELF-EFFICACY | Pearson correlation | 1 | ,327** | -,279* | ,243* | ||

| Sig. (bilateral) | ,003 | ,012 | ,029 | ||||

| MOTIVATION | Pearson correlation | 1 | ,000 | ,242* | |||

| Sig. (bilateral) | ,999 | ,030 | |||||

| ANXIETY | Pearson correlation | 1 | ,203 | ||||

| Sig. (bilateral) | ,070 | ||||||

| **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (bilateral). | |||||||

| *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (bilateral). | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).