1. Introduction

The intrinsic properties of ZnO, such as its wide bandgap energy, high melting point, thermal stability, strong piezoelectric effect, hexagonal wurtzite structure, and large exciton binding energy, have established it as a popular material in wide bandgap semiconductors [

1,

2]. These properties have led to its utilization in optical and optoelectronic applications, piezoelectric nanogenerators, gas sensing, and multifunctional nanodevices. Nevertheless, research has indicated that the closure of intrinsic defects and the shape-dependent properties of nanorods can significantly improve their performance. This positions ZnO as an ideal semiconductor oxide material for emerging applications and a model material for examining the properties of low-dimensional nanostructures [

3,

4,

5].

Specifically, because of ZnO's potential practical uses and numerous reports on matrix-doped ZnO, one of the most promising options is when ZnO is doped with silver nanoparticles. This addition has been proven to significantly improve the electrical and optical properties of ZnO nanorods, making them a desirable choice for various technological advancements in the fields of electronics, photonics, and optoelectronics[

6,

7].

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have exceptional optical and electrical properties that have generated significant interest in scientific and technological fields. These unique characteristics are due to their small size and quantum mechanical effects. Optically, silver nanoparticles are recognized for their intense surface plasmon resonance (SPR), where conduction electrons on the nanoparticle surface oscillate in response to light, leading to strong absorption and scattering of specific wavelengths and resulting in vibrant colors and enhanced electromagnetic fields near the particle surface. Electrically, silver nanoparticles have excellent conductivity due to their high electron mobility and large surface area-to-volume ratio, making them ideal for use in electronics, conductive inks, and sensors. Additionally, the quantum confinement effects in nanoparticles influence their electronic properties, leading to discrete energy levels and potentially enhanced reactivity compared to bulk silver[

8,

9,

10,

11].

To gain a deeper understanding and improve the properties of nanostructured materials, it is crucial to utilize advanced microscopy techniques. Popular techniques such as Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) and current mapping properties at the nanometer scale. These methods produce clearer potential images and are essential for determining the electrical properties of nanostructured materials, thus aiding in the development of advanced nanotechnologies[

12,

13,

14]

KPFM utilizes a dual-pass technique where a modulated voltage is applied to the cantilever tip as the oscillation frequency, followed by a phase-sensitive detection system to capture the frequency shift and the tip's work function relative to the sample. The alteration in the tip's work function induces an AC bias potential difference between the tip and sample, moving towards Fermi level equalization, deduced by the thermionic field emission effect. The rectified incremental bias ΔV is related to the work function difference between the tip and sample. This allows KPFM to study work functions on surfaces at a high resolution, down to the nanometer scale. KPFM is versatile, accurate, and non-destructive, making it suitable for studying electronic materials for next-generation electronic devices[

15,

16,

17,

18].

Electricity characteristics of materials on a nanoscale can be studied using current mapping and current-voltage (I-V) measurements with scanning probe microscopy (SPM). In current mapping, a conductive probe moves across the material's surface in constant contact or tapping mode, detecting local variations in electrical conductivity. This method offers precise spatial resolution, revealing different conductive areas and their electrical behaviors. On the other hand, I-V measurements involve applying a variable voltage between the probe and the sample while recording the resulting current. This helps determine important electronic properties like resistance, diode behavior, and charge carrier mobility. When used together, current mapping and I-V measurements reveal detailed information about electronic heterogeneity, charge transport mechanisms, and the impact of nanostructures on material performance[

19,

20,

21,

22].

The information gathered from the samples studied, including their work function, surface potential, current mapping, and band structure properties, allows us to gain a deeper understanding of their physical origins.

The primary focus of this research is to understand the fundamental properties of hybrid ZnO nanorods and silver nanoparticles. Electrical and optical characterization will be performed to verify the effectiveness of the hybrid system.

This study aims to comprehensively explore the work function and electrostatic force microscopy of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanorods and silver (Ag) nanoparticles. In addition to that, we will thoroughly examine the optical properties of the hybrid nanostructure of ZnO nanorods and silver nanoparticles. Moreover, we will conduct extensive investigations into the current-voltage characteristics of both ZnO nanorods and Ag nanoparticles, as well as the dynamic behavior of the hybrid structure, utilizing state-of-the-art current mapping techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. ZnO Nanorods and Ag Nanoparticles Synthesis

In our previous research[

23], we successfully generated ZnO nanorods by first heating a solution containing 5.5g of zinc acetate dehydrate (98+%, sigma Aldrich) in 250ml of ethanol until it became clear. The solution was then refluxed for 1 hour, with 150ml of the solvent removed by distillation and replaced with fresh ethanol. Subsequently, 1.39g of lithium hydroxide monohydrate (Aldrich) was added to the solution in an ultrasonic bath at 0℃ and dispersed for 1 hour, resulting in a transparent solution of ZnO sol-gel nanoparticles. To create the ZnO nanorods, the solution containing ZnO nanoparticles was heated and combined with

10% distilled water (DW) at 60℃ for 48 hours, resulting in the formation of a white powder-precipitate.

In another recent work[

24], silver nanoparticles were synthesized by mixing 1.18 mM AgNO3 aqueous solutions with deionized water. Subsequently, 50 mL of Pistacia Palaestina (P. Palaestina) leaf extract was added drop by drop to each 50-mL AgNO3 solution... The mixture was then warmed in a heating mantle, maintaining a temperature range of 80 to 84 °C for 2 hours with continuous stirring. The successful formation of silver nanoparticles was indicated by the emergence of a brownish-yellow to black color. To purify the synthesized nanoparticles, the solution was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes, a process that was repeated five times to ensure the retrieval of pure silver nanoparticles.

2.2. Deposition and Characterization Methods

We deposited ZnO nanorods and silver nanoparticles on various substrates such as mica sheet, P-type silicon substrate, metal steel, and glass for different characterization purposes. The morphology, KPFM, and current mapping characteristics of the ZnO nanorods, silver nanoparticles, and their hybrid were evaluated using Scanning Probe Microscopy (SPM-9700HT, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). To analyze the electrical conductivity, and work function, we utilized AFM and KPFM for these measurements. These methodologies allowed for precise determinations of the nanoparticles’ conductivity, morphology, and surface potential. The samples were carefully placed on a piezoelectric stage for examination, and a conductive probe made of PtSi was attached to the end of the cantilever. This setup allowed for a uniform oscillatory motion as the probe traversed the sample’s surface, providing a comprehensive map of its topography. KPFM further enriched our analysis by generating images of the surface potential alongside the topographic map at each point of the scan. The interaction between the probe and the sample surface includes an electrostatic force component, originating from the contact potential difference (CPD) between them, providing valuable data on the surface potential. Proper preparation of the samples was crucial for precise topographic and potential mapping, with each sample fixed to carbon tape and securely fastened to a steel disc to ensure stability during scanning. The scanning was performed at a speed of 0.5 Hz and a resolution of 256 × 256 pixels, delivering high-definition images, and the instrument’s spatial resolution was recorded at 0.2 nm. Localized nanoscale current mapping measurements were conducted using the C-AFM (Conductive Atomic Force Microscopy) technique, which is widely recognized for its high spatial resolution. To obtain the measurements, Nanoworld supplied Pt/Ir-coated tips with a resonance frequency of 13 kHz and a force constant of 0.2 N/m, selected for their excellent conductive properties. These tips were used as the top electrode for the purpose of understanding the current-voltage (I-V) characteristics using the C-AFM technique. The I-V response, which offers valuable insight into the electrical behavior of the sample, was carefully derived from the recorded current images. This was achieved by sweeping the bias voltage within the range of -5V to +5V while keeping a constant sample bias of 3V.. The X-ray diffraction analysis was conducted using a Bruker D2 PHASER (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) with Cu kα radiation settings of 30 kV and 10 mA. The UV–vis absorption spectra were acquired using a UV-2600i spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan), and photoluminescence spectra were captured with an RF-6000 spectrofluorometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). Data collection was performed using Shimadzu LabSolutions software.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphology and Structure of ZnO-NR and Ag-NP

The shape, length, and height of the ZnO nanorods and Ag nanoparticles were carefully examined using Scanning Probe Microscopy (SPM) topography images captured in a non-contact dynamic mode. In order to conduct this examination, a Super Sharp Silicon (SSS-NCH) AFM tip from Nanoworld, possessing a force constant of 42 N/m, a resonance frequency of 320 kHz, and a tip radius of 2 nm, was utilized. As depicted in

Figure 1 (a, b, c, ), the provided atomic force microscopy (AFM) topographic representation of ZnO nanorods on a Si substrate successfully reveals the morphology and length of the nanorods, which have been determined to be approximately 350 nm, as illustrated in

Figure 1 (c). Moving on to

Figure 1 (d, e, f, ), it displays silver nanoparticles on a mica substrate, showcasing their spherical morphology quite explicitly. Conducting height analysis as shown in

Figure 1 (f) facilitated the determination that the observed heights of these nanoparticles range from 5 to 14 nm. Finally,

Figure 1 (h,g, i) showcases hybrid ZnO nanorods and silver nanoparticles.

For more details about the crystal structure of the ZnO nanorods and Ag nanoparticles, as depicted in

Figure 2 which illustrates a typical XRD pattern of the ZnO nanorods. The sharpness of the peaks signifies the high level of crystallinity of the ZnO nanorods, demonstrating a single-phase wurtzite structure. The observed diffraction peaks are associated with the existence of pure hexagonal phase of ZnO with lattice constants of a = 3.251 Å and c = 5.208 Å, consistent with JCPDS card for ZnO (JCPDS, 036-1451)[

25]. The crystalline diameter of ZnO nanorods is approximated to be 20 nm, calculated employing the Debye-Scherer’s formula. This formula takes into account various factors, including the crystallite size, wavelength of the X-ray used, and the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the observed diffraction peak. By applying this formula, we can estimate the size of the ZnO nanorods, providing crucial information about their physical properties[

26]. Furthermore, the XRD patterns of silver nanoparticles reveal peaks at 2θ angles of 38.4°, 44.7°, 64.6°, and 77.7°, corresponding to the (111), (200), (220), (311) planes, indicating the crystalline phase of silver metal with a face-centred cubic structure, consistent with the JCPDS File No. 04-0783. These diffraction peaks allow us to determine the orientation and arrangement of the atoms within the silver nanoparticles, providing valuable insights into their structural properties[

27].

3.2. Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy of ZnO-NR and Ag-NP (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the KPFM characteristics of ZnO nanorods and Ag nanoparticles on a silicon substrate. The detailed images reveal the electrical interaction between the probe and the sample, with high potential shown as red and low potential as yellow for the ZnO nanorods and Ag nanoparticles. The average contact potential difference (CPD) for ZnO nanorods with a 30 nm diameter and 400 nm length is approximately 96 mV. Similarly, ZnO nanorods with a 20 nm diameter and 220 nm length have a contact potential difference of 81 mV. In contrast, nanorods with an 8 nm diameter and 130 nm length show a contact potential difference of 56 mV. These results emphasize the influence of ZnO nanorod dimensions on the contact potential difference, as illustrated in

Figure 3 (c,d).. The AFM topography and KPFM images of Ag nanoparticles of varying sizes are shown in

Figure 4. The average CPD for the Ag nanoparticles is 46 mV for a size of 4 nm, and 70 mV for sizes 13 nm, as illustrated in

Figure 4(d).

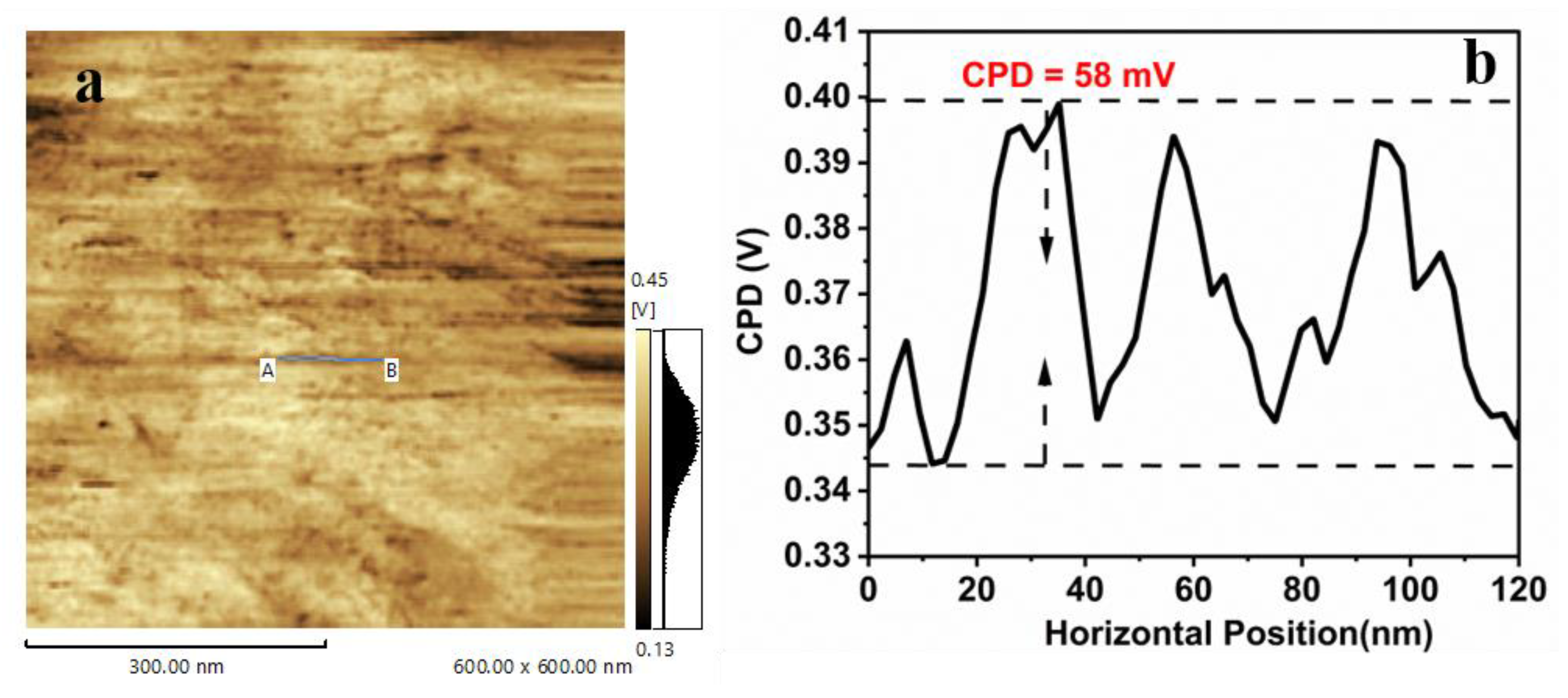

Figure 5 displays the KPFM for a reference sample of Highly Ordered Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG), grade ZYA. This sample has a mosaic spread of 0.4 ± 0.1° and dimensions of 10 mm by 10 mm with a thickness of 1 mm. The average Contact Potential Difference (CPD) for this sample is approximately 58 mV, as shown in

Figure 5(b). It was provided by MikroMasch.

The main goal of Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM) is to accurately measure the work function of a specific sample. A key factor in KPFM is the surface potential, which represents the difference in work function values between the sample surface, denoted as

, and the tip of the AFM probe, represented as

. This difference is mathematically defined by the equation:

Where 'e' represents the charge of a single electron, and

is the Contact Potential Difference between the probe tip and the sample's surface[

28]. To obtain an accurate assessment of the work function of ZnO nanorods, it is necessary to determine the work function of the cantilever within the apparatus. Calibration is important to ensure the reliability of measurements and typically involves the use of a reference material with a known work function for standardization purposes. In this study, Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG) is used as the reference material, with a work function range of 4.5 to 5 eV, serving as a benchmark for calibration and precision of measurements[

29].

Using Equation (1), similar formulas are derived for both ZnO nanorods and HOPG substrates. The work function of the ZnO nanorods substrate is denoted as and the specific Contact Potential Difference for ZnO nanorods substrate is represented as V(CPD, ZnO-NR). Similarly, the work function for the HOPG substrate is , and its unique Contact Potential

Difference is V

(CPD, HOPG), The difference between the work functions of these two substrates can be determined using the following equations:

Using the equation 2 and CPD values from the analysis in

Figure 3 (c,d) and

Figure 5 (b) and the published values for HOPG's work function, the work function of ZnO nanorods was accurately estimated. For ZnO nanorods with approximately 30 nm diameter and 400 nm length, the work function was calculated to be 4.556 eV. Additionally, for ZnO nanorods with a diameter of around 20 nm and a length of 220 nm, the work function was estimated to be 4.527 eV. On the other hand, for ZnO nanorods with a diameter of 8 nm and a length of 130 nm, the work function was found to be 4.552 eV. Our calculation of the work function for ZnO nanorods is approximately 4.55 eV, which is higher than the work function of ZnO bulk, typically around 4.45 eV[

30]. The difference in work function values observed between ZnO nanorods and bulk ZnO is attributed to various factors. Quantum confinement, influenced by the nanorods' size, restricts electron movement, leading to higher energy levels and an increased work function. Nanorods also have a greater surface-to-volume ratio compared to bulk materials, leading to changes in electronic structure and possibly increased surface energy, resulting in a higher work function[

31].

In the context of calculating the work function of silver nanoparticles, we use Equation (1) and can also create similar equations for both Ag nanoparticles and HOPG substrates. By representing the work function of the silver nanocluster substrate as ∅

Ag and the specific contact potential difference for the silver nanoparticles substrate as

V(CPD,Ag), we can then denote the work function of the HOPG substrate as ∅

HOPG and its unique contact potential difference as

V(CPD,HOPG) . The relationship between the work functions of silver and HOPG is connected through their respective Contact Potential Differences:

Using Equation (3) and the Contact Potential Difference (CPD) data from

Figure4(d) and

Figure 5 (b), along with the work function value of HOPG from the literature [

32], the work function of the AgNPs with an average diameter of 4 nm was determined to be 4.56 eV. For nanoparticles of size 14 nm, the work function equals 4.538 eV.

From literature sources, the work function of bulk silver is known to be 4.3 eV, while the work function of Ag nanocluster is 4.587 eV [

32], and a vacuum-deposited Ag electrode is 4.68 eV. The work function of the Ag nanoparticles is estimated to be around 4.56 eV and 4.54, which aligns closely with the values reported in the literature.

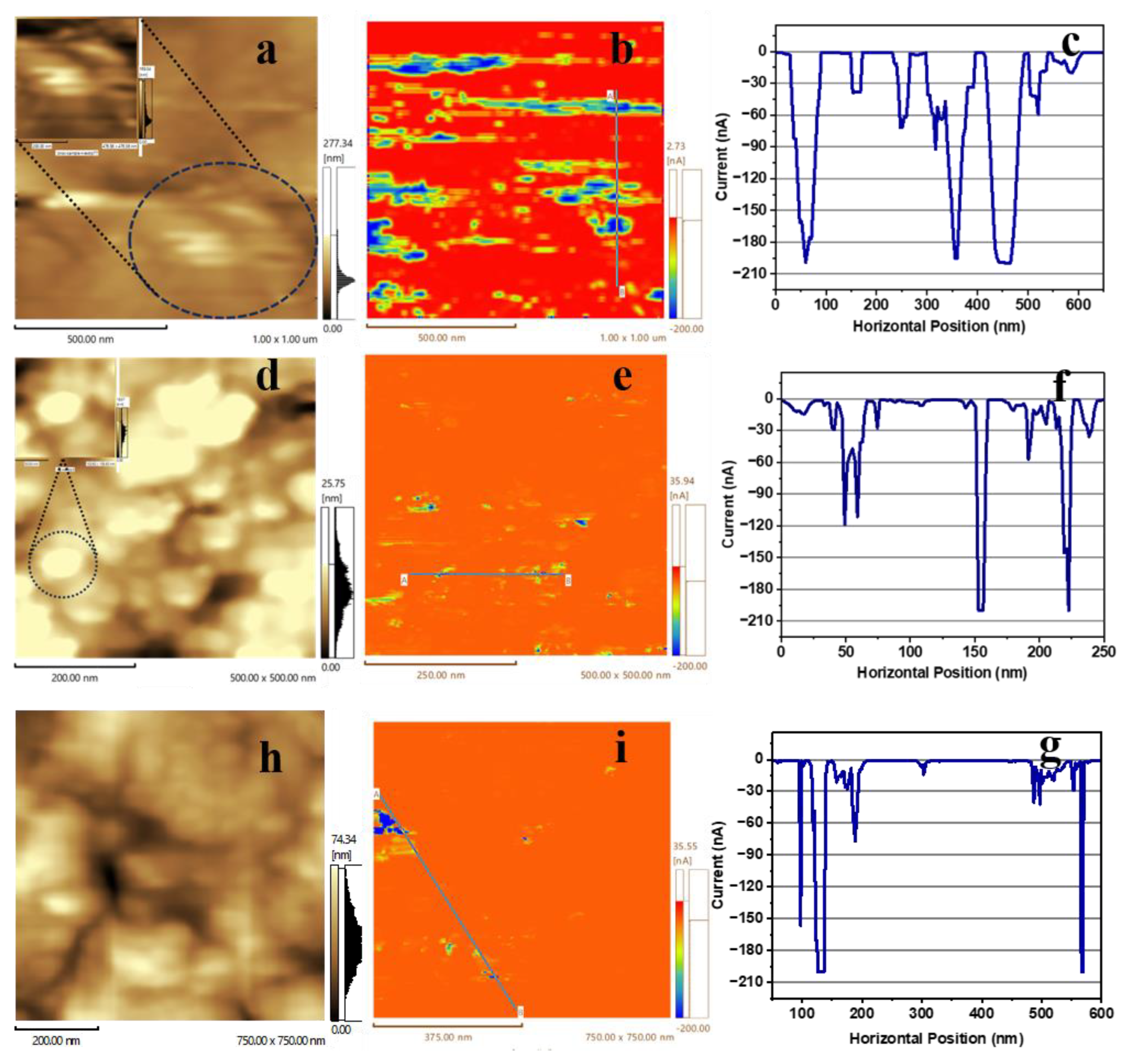

3.3. Current Mapping and I-V Measurements

We present an electrical analysis of Zinc Oxide (ZnO) nanorods, silver nanoparticles (AgNP), and a hybrid material using conductive atomic force microscopy (C-AFM). This advanced method enables the simultaneous recording of current maps and topography obtained through contact mode AFM. Additionally, C-AFM allows for the precise determination of the local current-voltage (I-V) characteristics of the top surface of ZnO nanorods, silver nanoparticles, and the hybrid composite material as shown in

Figure 6 and Figure 7. By applying voltage through a conductive tip in contact with the ZnO nanorods' surface, variations in electrical current can be detected, unveiling defects and surface states. This method enables precise control and adjustment of the electrical properties of the ZnO nanorods.

Distinct areas with heightened and reduced current values, depicted in

Figure 6 (c), point out significant regions such as defects or highly conducting pathways. Scattered yet noteworthy regions of elevated current indicate localized areas of high conductivity or possible defects, with current values equal to or exceeding 150 nA. Conversely, widespread low current sections cover most of the image, indicating general low conductivity or a consistent baseline current level throughout the ZnO nanorods, with current values equal to or less than 10 nA. Furthermore, for Ag nanoparticles, the high current region ranges from 120 nA to 200 nA, possibly linked to differences in their size. Similarly, for hybrid ZnO-NR and Ag-NP, the high current region falls between 160 nA and 200 nA, as seen in

Figure 6 (g).

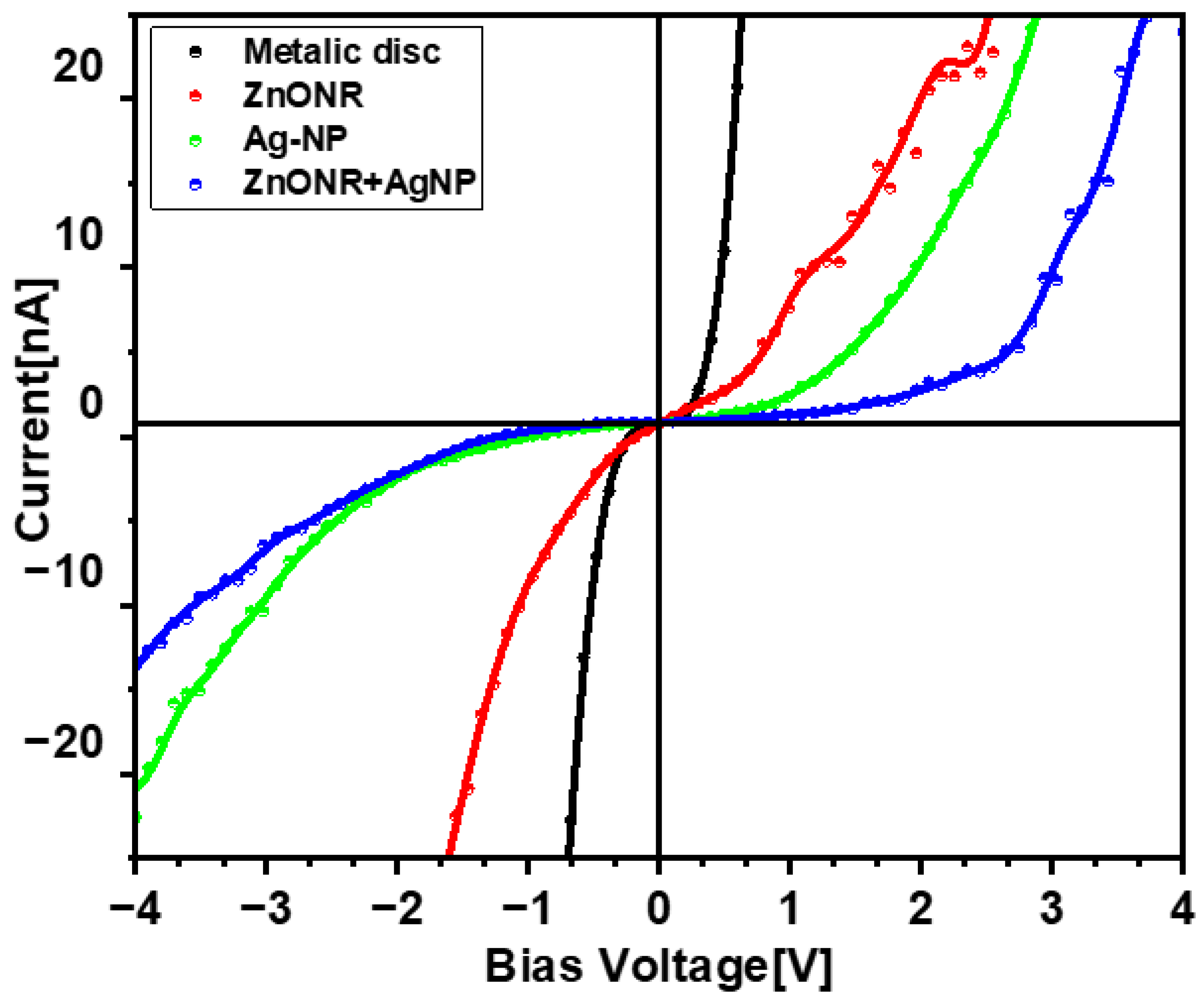

The results presented in

Figure 7 show a typical I-V characteristic curve obtained from metallic disc as reference sample , ZnO nanorods (ZnONR), silver nanoparticles (Ag-NP), and a combination of ZnO-NR and Ag-NP samples. The findings reveal a significant increase in current at approximately 1V for both ZnO-NR and Ag-NP, indicating turn-on voltages of around 1V for each. When combined, there is a different turn-on voltage around 2.5 V, suggesting a unique response to the combined effect. The reverse bias analysis also highlights the distinctive characteristics of the ZnONR and Ag-NP combination, effectively blocking current until very high negative voltages. It is important to understand that the presence of Ag-NP significantly impacts the electrical properties of ZnONR. The observed effects in the I-V traits for ZnO nanorods (ZnONR), silver nanoparticles (Ag-NP), and their combination requires a thorough understanding of the physical and chemical interactions between these materials.

In analyzing the reasons for the increase in current at around 2.5 V, it is necessary to consider the intrinsic characteristics of ZnO nanorods and silver nanoparticles. ZnO is a wide-bandgap semiconductor, and in forward bias, significant current flows once the voltage exceeds the built-in potential barrier. The presence of silver nanoparticles, which are exceptional conductors, also aids in charge transport. The combination of ZnONR with Ag-NP can create a Schottky junction, improving carrier injection at the interface, and can slightly alter the turn-on voltage compared to individual components. The presence of Ag-NP can introduce new surface states and modify existing defects in ZnONR, impacting the overall conduction mechanism. Additionally, it can enhance the barrier height in reverse bias due to the Schottky effect, indicating improved stability and robustness of the device.

Furthermore, the presence of Ag-NP can enhance the mobility of charge carriers in ZnONR by providing additional pathways and reducing scattering[

33]. It can also passivate surface defects, reducing trap states and enhancing charge transport. The interaction between Ag-NP and ZnONR can modify the band structure, leading to changes in electrical properties. It is worth mentioning that a Schottky diode with a higher threshold voltage can be fabricated from various semiconductor materials, including Silicon Carbide (SiC) or Gallium Nitride (GaN)[

34]. However, the combination of ZnO nanorods and silver nanoparticles offers a more cost-effective synthesis option in this particular study.

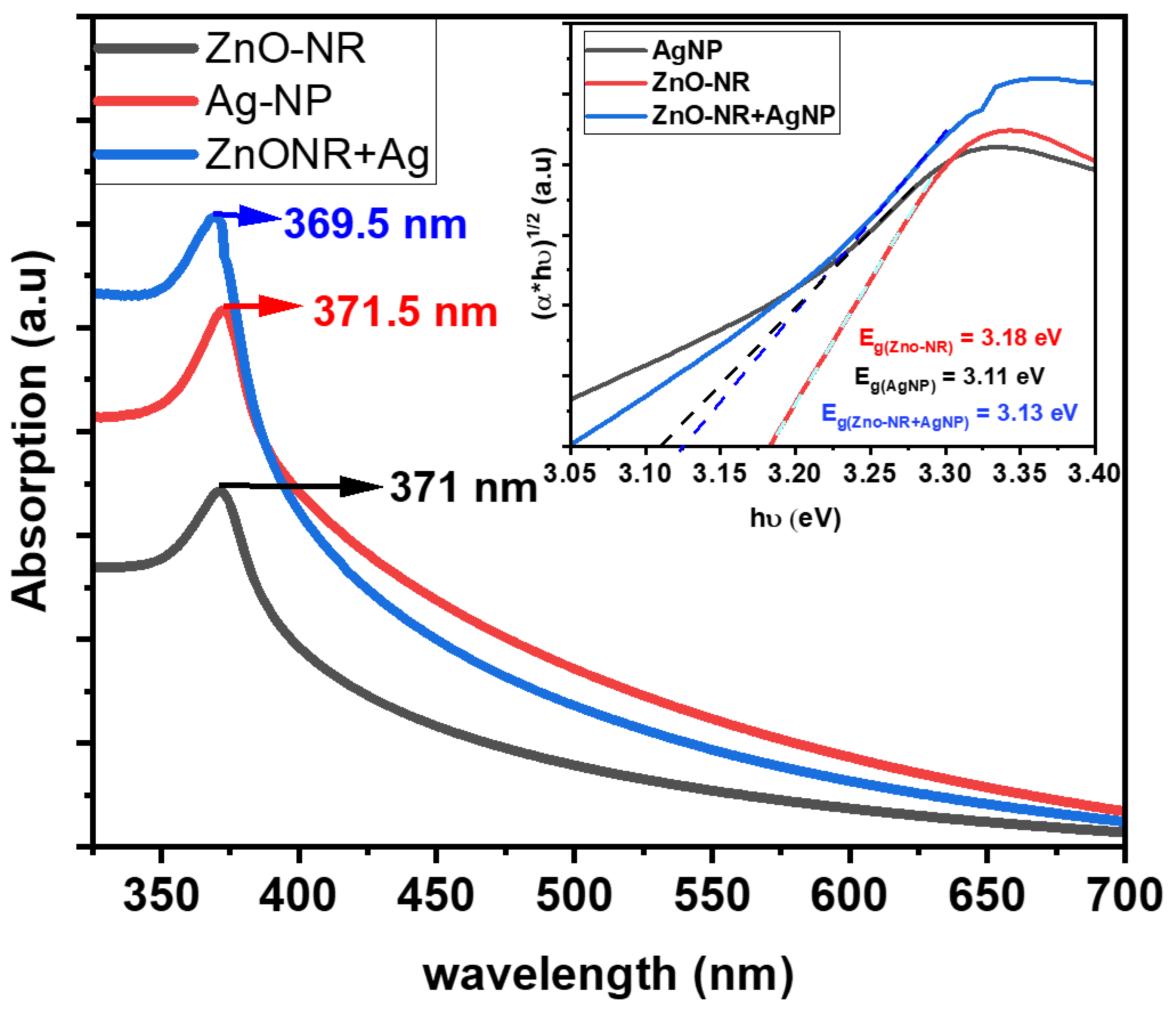

3.4. Optical Properties of Hybrid of ZnO-NR and Ag-NP

Figure 8 depicts the absorption characteristics of ZnO nanorods (ZnO-NR), silver nanoparticles (AgNP), and the ZnO-NR+AgNP hybrid. ZnO nanorods are renowned for their unique composition and structure, displaying a distinct absorption peak at the bandgap energy level, typically around 3.11 eV. In contrast, Ag nanoparticles exhibit absorption traits influenced by surface plasmon resonance, with a well-defined absorption peak near 3.18 eV[

35].

The alteration in the absorption spectrum when ZnO-NR and AgNP combine to form the ZnO-NR+AgNP hybrid is of particular interest. This change signifies a close interaction between the ZnO nanorods and Ag nanoparticles, resulting in a synergistic effect that enhances overall absorption performance. Specifically, the bandgap energy of the hybrid material experiences a slight shift, settling at approximately 3.13 eV. While seemingly small, this shift holds great significance as it indicates the enhanced absorption capabilities of the hybrid material. The slight change in bandgap energy, approximately 3.13 eV, between the hybrid ZnO nanorods and Ag nanoparticles is significant for several reasons. The surface plasmon resonance effect of Ag nanoparticles can enhance the electromagnetic field nearby and increase light absorption, impacting the properties of ZnO nanorod. Additionally, the interaction between the two materials can result in charge transfer, altering the electronic structure of ZnO and causing a minor shift in bandgap energy. The size and distribution of Ag nanoparticles can also influence the electronic properties of ZnO, with quantum size effects coming into play due to the confinement of charge carriers at the nanoscale[

36,

37].

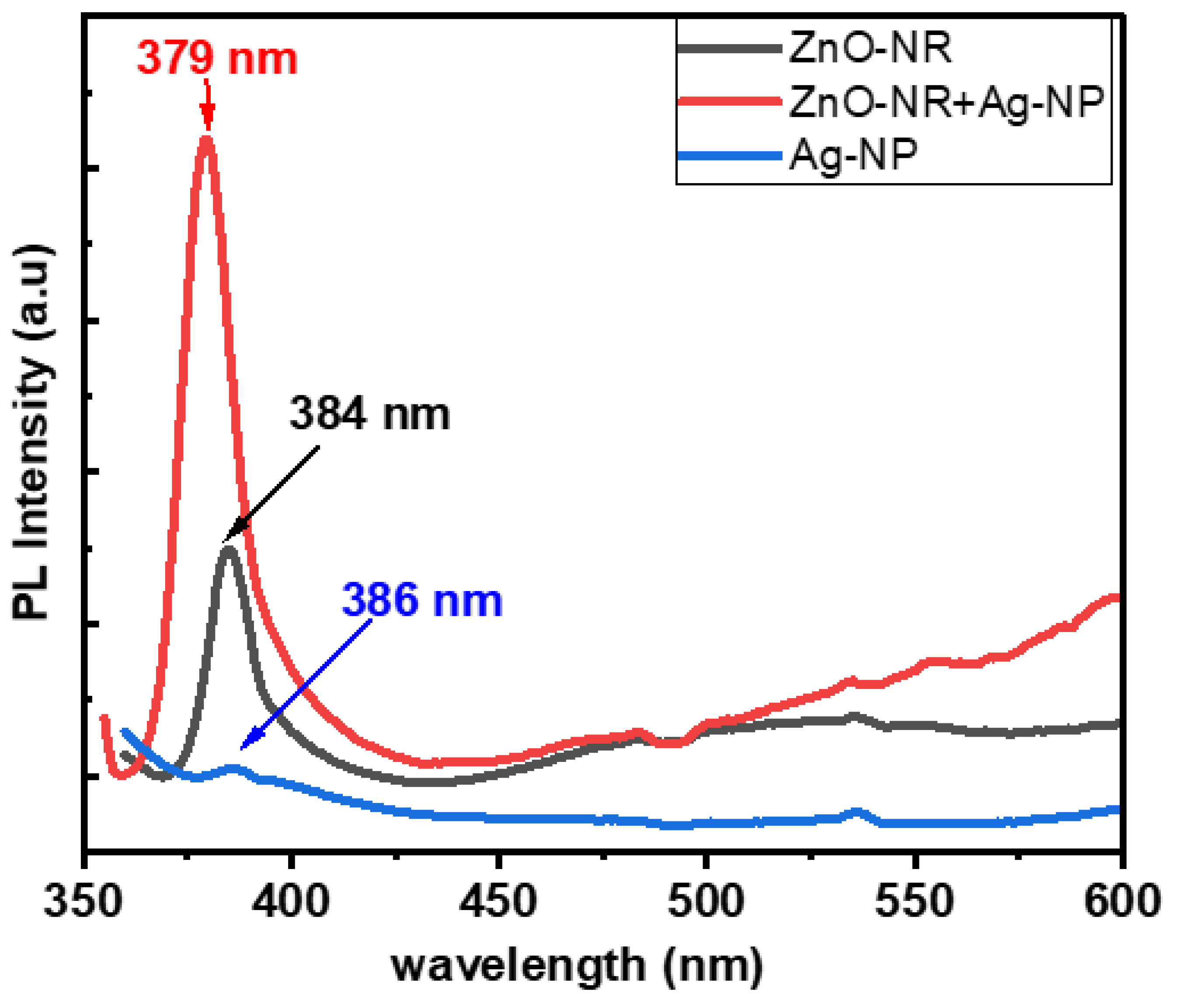

The photoluminescence spectra in

Figure 9 show the presence of ZnO nanorods and Ag nanoparticles, with peaks at 384 nm and 386 nm, respectively. The addition of Ag nanoparticles at 379 nm has a significant effect on the optical characteristics of ZnO nanorods, resulting in increased photoluminescence intensity and changes in peak positions. This change is likely due to the plasmonic effects of the Ag nanoparticles and their interaction with the ZnO nanorods.

The addition of Ag nanoparticles causes a noticeable shift and change in intensity in the PL spectrum, with a shift from 379 nm to 386 nm, suggesting fundamental alterations in the electronic structure and energy states of ZnO nanorods. The heightened PL intensity for the hybrid structures indicates improved photoluminescence as a result of the strong interaction between ZnO nanorods and Ag nanoparticles.

One potential mechanism for the observed changes in PL intensity and peak positions is the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) of Ag nanoparticles, which can significantly enhance the local electromagnetic field and the PL intensity of ZnO nanorods. Another potential mechanism is the transfer of charge between the ZnO nanorods and Ag nanoparticles, which can affect the recombination rate of electron-hole pairs in ZnO, leading to variations in PL intensity and peak positions[

38,

39].

4. Conclusions

The detailed analysis of ZnO nanorods and silver nanoparticles provided valuable insights into their physical, structural, electrical, and optical characteristics. Utilizing Scanning Probe Microscopy (SPM) and X-ray Diffraction (XRD), it was determined that the ZnO nanorods exhibited a distinct shape, with lengths of around 350 nm and a highly crystalline, single-phase wurtzite structure. The silver nanoparticles, on the other hand, displayed a spherical shape with heights ranging from 5 to 14 nm and were confirmed to be composed of silver metal with a face-centered cubic structure. Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM) measurements offered further insights into the work function and contact potential differences (CPD) of these nanomaterials. It was revealed that the work function of ZnO nanorods varied with size, ranging from approximately 4.556 eV to 4.527 eV, while the work function of Ag nanoparticles ranged from 4.56 eV to 4.538 eV. Conductive atomic force microscopy (C-AFM) was employed to investigate the electrical properties of these materials, uncovering regions of both high and low current in both the ZnO nanorods and the Ag nanoparticles. The hybrid ZnO-NR and Ag-NP material exhibited a unique electrical response, with a combined turn-on voltage of around 2.5 V. The optical properties of the ZnO-NR and Ag-NP hybrid were examined through absorption and photoluminescence (PL) spectra. The hybrid material demonstrated enhanced absorption capabilities, a shift in bandgap energy, and alterations in the photoluminescence peak and intensity. These findings highlight the positive impact of the hybridization of ZnO-NR and Ag-NP on their optical and electrical properties, positioning them as promising candidates for advanced nanotechnology applications.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Palestine Technical University—Kadoorie (PTUK) for facilities and support.

References

- Que, M.; Lin, C.; Sun, J.; Chen, L.; Sun, X.; Sun, Y. Progress in ZnO Nanosensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, H.; Ramakrishna, S. Piezoelectric Materials for Flexible and Wearable Electronics: A Review. Materials & Design 2021, 211, 110164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eka Putri, A.; Roza, L.; Budi, S.; Ali Umar, A.; Fauzia, V. Tuning the Photocatalytic Activity of Nanocomposite ZnO Nanorods by Shape-Controlling the Bimetallic AuAg Nanoparticles. Applied Surface Science 2021, 536, 147847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefatshe, K.; Dube, P.; Sebuso, D.; Madhuku, M.; Muiva, C. Optical Dispersion Analysis of Template Assisted 1D-ZnO Nanorods for Optoelectronic Applications. Ceramics International 2021, 47, 7407–7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyszko, M.; Zywicka, A.; Wenelska, K.; Mijowska, E. Revealing the Influence of the Shape, Size, and Aspect Ratio of ZnO Nanoparticles on Antibacterial and Mechanical Performance of Cellulose Fibers Based Paper. Particle & Particle Systems Characterization 2022, 39, 2200014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulahlib, S.; Dib, K.; Özacar, M.; Bessekhouad, Y. Optical, Dielectric, and Transport Properties of Ag-Doped ZnO Prepared by Aloe Vera Assisted Method. Optical Materials 2021, 113, 110889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutalib, M.M.; Rajeh, A. Influence of ZnO/Ag Nanoparticles Doping on the Structural, Thermal, Optical and Electrical Properties of PAM/PEO Composite. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2020, 578, 411796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Verma, D.; Okram, G.S. Influence of Surfactant, Particle Size and Dispersion Medium on Surface Plasmon Resonance of Silver Nanoparticles. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2020, 32, 145302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehata, M.S. Green Route Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Plants/Ginger Extracts with Enhanced Surface Plasmon Resonance and Degradation of Textile Dye. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2021, 273, 115418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, F.Y.; Ahmad, A.A.; Aljarrah, I.A.; Migdadi, A.B.; Al-Bataineh, Q.M. Localize Surface Plasmon Resonance of Silver Nanoparticles Using Mie Theory. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 2023, 34, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma, M.W.; Birech, Z.; Mwenze, N.M.; Ondieki, A.M.; Maaza, M.; Mokhotjwa, S.D. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensing of Trenbolone Acetate Dopant Using Silver Nanoparticles. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 5721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checa, M.; Neumayer, S.M.; Tsai, W.-Y.; Collins, L. Advanced Modes of Electrostatic and Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy for Energy Applications. In Atomic Force Microscopy for Energy Research; CRC Press, 2022; ISBN 978-1-00-317404-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Cao, G.; Xie, L.; Huang, W. Injection and Retention Characterization of Trapped Charges in Electret Films by Electrostatic Force Microscopy and Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy. physica status solidi (a) 2020, 217, 2000190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, X.; Liu, M.; Sun, L.; Qiu, X. Electrical Characteristics of a Carbon Nanotube-Functionalized Probe for Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 28261–28266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, D.S.; Li, N.; Zhou, H.; Xu, X.G. Integrated Tapping Mode Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy with Photoinduced Force Microscopy for Correlative Chemical and Surface Potential Mapping. Small 2021, 17, 2102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackl, T.; Poik, M.; Schitter, G. Heterodyne AC Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy for Nanoscale Surface Potential Imaging in Liquids. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grévin, B.; Husainy, F.; Aldakov, D.; Aumaître, C. Dual-Heterodyne Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy. Beilstein J Nanotechnol 2023, 14, 1068–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryon, O.O.; Efaw, C.M.; DelRio, F.W.; Graugnard, E.; Hurley, M.F.; Davis, P.H. Co-Localizing Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy with Other Microscopies and Spectroscopies: Selected Applications in Corrosion Characterization of Alloys. JoVE 2022, 64102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, P.S.; Mativetsky, J.M. Unambiguous Measurement of Local Hole Current in Organic Semiconductors Using Conductive Atomic Force Microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 9903–9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Quintana, I.; Amargós-Reyes, O.; Maldonado, J.-L.; Nicasio-Collazo, J.; Romero-Borja, D.; Barreiro-Argüelles, D.; Molnár, G.; Bousseksou, A. Scanning Probe Microscopy Analysis of Nonfullerene Organic Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 29520–29527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, R.; Alvarez, J.; Ohashi, T.; Martín, I.; Ortega, P.; Lopez, G.; Jin, C.; Li, Z.; Rusli, -; Bulkin, P.; et al. Observation of Photovoltaic Effect within Locally Doped Silicon Nanojunctions Using Conductive Probe AFM. Nano Energy 2020, 76, 105072. [CrossRef]

- Barrigón, E.; Hrachowina, L.; Borgström, M.T. Light Current-Voltage Measurements of Single, as-Grown, Nanowire Solar Cells Standing Vertically on a Substrate. Nano Energy 2020, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, I.; Qamhieh, N.; Mahmoud, S.T. Synthesis and Length Dependent Photoluminescence Property of Zinc Oxide Nanorods. Results in Physics 2017, 7, 3552–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, I.; Mousa, R. Synthesis and Characterization of Variable-Sized Silver Nanoparticles Using Pistacia Palaestina Leaf Extract. Plasmonics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, P.L.; Bhardwaj, P.; Kumar, Y.; Singh, S.P. Synthesis and Characterization of One Dimensional ZnO Nanorods. AIP Conference Proceedings 2021, 2352, 040043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, I.; Qamhieh, N. STUDY OF OPTICAL ENERGY GAP AND QUANTUM CONFINMENT EFFECTS IN ZINC OXIDE NANOPARTICLES AND NANORODS.

- Ali, Md.H.; Azad, Md.A.K.; Khan, K.A.; Rahman, Md.O.; Chakma, U.; Kumer, A. Analysis of Crystallographic Structures and Properties of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using PKL Extract and Nanoscale Characterization Techniques. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 28133–28142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glatzel, T.; Gysin, U.; Meyer, E. Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy for Material Characterization. Microscopy 2022, 71, i165–i173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, I.; Faqi, R. Structural, Electrostatic Force Microscopy, Work Function, and Optical Characterization of Pure and Al-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles. Results in Materials 2024, 22, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Y.K.; Chakravadhanula, V.S.K.; Hrkac, V.; Jebril, S.; Agarwal, D.C.; Mohapatra, S.; Avasthi, D.K.; Kienle, L.; Adelung, R. Crystal Growth Behaviour in Au-ZnO Nanocomposite under Different Annealing Environments and Photoswitchability. Journal of Applied Physics 2012, 112, 064308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahana, M.B.; Sudakar, C.; Dixit, A.; Thakur, J.S.; Naik, R.; Naik, V.M. Quantum Confinement Effects and Band Gap Engineering of SnO2 Nanocrystals in a MgO Matrix. Acta Materialia 2012, 60, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, I.; Qamhieh, N.; Mahmoud, S.T. Ag Nanocluster Production through DC Magnetron Sputtering and Inert Gas Condensation: A Study of Structural, Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy, and Optical Properties. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thappily, P.; Mandin, P.; Sauvage, T.; Sandhya, K. Enhancement of Charge Transport Properties of a Novel Rubbery Semiconductor via Silver Nanocomplexing. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2021, 131, 105854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Moradpour, M.; Losito, M.; Franke, W.-T.; Ramasamy, S.; Baccoli, R.; Gatto, G. Wide Band Gap Devices and Their Application in Power Electronics. Energies 2022, 15, 9172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.; Troc, N.; Cottancin, E.; Pellarin, M.; Weissker, H.-C.; Lermé, J.; Kociak, M.; Hillenkamp, M. Plasmonic Quantum Size Effects in Silver Nanoparticles Are Dominated by Interfaces and Local Environments. Nat. Phys. 2019, 15, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Ananthakrishnan, R. Double Effects of Interfacial Ag Nanoparticles in a ZnO Multipod@Ag@Bi2S3 Z-Scheme Photocatalytic Redox System: Concurrent Tuning and Improving Charge-Transfer Efficiency. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 7681–7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.; Qiu, G.; Ye, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, D. ZnO/Ag Nanorods as a Prominent SERS Substrate Contributed by Synergistic Charge Transfer Effect for Simultaneous Detection of Oral Antidiabetic Drugs Pioglitazone and Phenformin. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2020, 307, 127634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ye, Q.; Bai, L.-H.; Su, X.; Wang, T.-T.; Peng, T.-W.; Zhai, X.-Q.; Huo, Y.; Wu, H.; Liu, C.; et al. Enhanced UV Emission from ZnO on Silver Nanoparticle Arrays by the Surface Plasmon Resonance Effect. Nanoscale Res Lett 2021, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauwel, P.; Galeckas, A.; Rauwel, E. Enhancing the UV Emission in ZnO–CNT Hybrid Nanostructures via the Surface Plasmon Resonance of Ag Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

a) Atomic force microscopy (AFM) topography images of ZnO nanorodss on a Si substrate, Scan sizes: (2.33 μm × 2.33 μm);(b)Three-dimensional projection topography of ZnO-NR. (c) line profiles for ZnO-NRs identified in the image b. (d) AFM topography image of Ag nanoparticles on a mica substrate, Scan sizes: (4 μm × 4 μm);(e)Three-dimensional projection topography of Ag-NP. (f) line profiles for AgNP identified in the image (e) (g) AFM topography image of hybrid Ag NP and ZnO NR on a si substrate, Scan sizes: (1.5 μm × 1.5 μm);(h)Three-dimensional projection topography of hybrid Ag NP and ZnO-NR. (i) line profiles for AgNP identified in the imag (h).

Figure 1.

a) Atomic force microscopy (AFM) topography images of ZnO nanorodss on a Si substrate, Scan sizes: (2.33 μm × 2.33 μm);(b)Three-dimensional projection topography of ZnO-NR. (c) line profiles for ZnO-NRs identified in the image b. (d) AFM topography image of Ag nanoparticles on a mica substrate, Scan sizes: (4 μm × 4 μm);(e)Three-dimensional projection topography of Ag-NP. (f) line profiles for AgNP identified in the image (e) (g) AFM topography image of hybrid Ag NP and ZnO NR on a si substrate, Scan sizes: (1.5 μm × 1.5 μm);(h)Three-dimensional projection topography of hybrid Ag NP and ZnO-NR. (i) line profiles for AgNP identified in the imag (h).

Figure 2.

The XRD pattern of ZnO nanorods and Ag nanoparticles.

Figure 2.

The XRD pattern of ZnO nanorods and Ag nanoparticles.

Figure 3.

(a) AFM topography images of ZnO nanorods on a Si substrate, Scan sizes: (3.5 μm × 3.5 μm);(b) line profiles for variable size and length of ZnO-NRs identified in the image (a). (c) surface potential images of ZnO NRs deposit on the Silicon substrate.( d) CPD line profiles for different sizes and length of ZnO NRs identified in image (c).

Figure 3.

(a) AFM topography images of ZnO nanorods on a Si substrate, Scan sizes: (3.5 μm × 3.5 μm);(b) line profiles for variable size and length of ZnO-NRs identified in the image (a). (c) surface potential images of ZnO NRs deposit on the Silicon substrate.( d) CPD line profiles for different sizes and length of ZnO NRs identified in image (c).

Figure 4.

(a) AFM topography images of Ag nanoparticles on a Si substrate, Scan sizes: (3.5 μm × 3.5 μm);(b) line profiles for variable Ag nanoparticles identified in the image (a). (c) surface potential images of Ag nanoparticles deposit on the Silicon substrate.( d) CPD line profiles for different sizes Ag nanoparticles identified in image (c).

Figure 4.

(a) AFM topography images of Ag nanoparticles on a Si substrate, Scan sizes: (3.5 μm × 3.5 μm);(b) line profiles for variable Ag nanoparticles identified in the image (a). (c) surface potential images of Ag nanoparticles deposit on the Silicon substrate.( d) CPD line profiles for different sizes Ag nanoparticles identified in image (c).

Figure 5.

(a) surface potential of reference sample Highly Ordered Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG), and (b) height profile (CPD) of HOPG extract from image (a).

Figure 5.

(a) surface potential of reference sample Highly Ordered Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG), and (b) height profile (CPD) of HOPG extract from image (a).

Figure 6.

a)AFM topography images of ZnO nanorodss on a metallic disc substrate, Scan sizes: (1 μm × 1 μm);(b) current mapping of ZnO-NR. (c) line profiles of current for ZnO-NRs identified in the image b. (d) AFM topography image of Ag nanoparticles on a metallic disc substrate, Scan sizes: (0.5 μm × 0.5 μm);(e) current mapping of Ag-NP. (f) line profiles of current for AgNP identified in the image (e) (g) AFM topography image of hybrid Ag NP and ZnO NR on a metallic disc substrate, Scan sizes: (0.75 μm × 0.75 μm);(h) ) current mapping of hybrid Ag NP and ZnO-NR. (g) line profiles of current for AgNP and ZnO-NR identified in the imag (i).

Figure 6.

a)AFM topography images of ZnO nanorodss on a metallic disc substrate, Scan sizes: (1 μm × 1 μm);(b) current mapping of ZnO-NR. (c) line profiles of current for ZnO-NRs identified in the image b. (d) AFM topography image of Ag nanoparticles on a metallic disc substrate, Scan sizes: (0.5 μm × 0.5 μm);(e) current mapping of Ag-NP. (f) line profiles of current for AgNP identified in the image (e) (g) AFM topography image of hybrid Ag NP and ZnO NR on a metallic disc substrate, Scan sizes: (0.75 μm × 0.75 μm);(h) ) current mapping of hybrid Ag NP and ZnO-NR. (g) line profiles of current for AgNP and ZnO-NR identified in the imag (i).

Figure 7.

Local I-V characteristic of metallic disc (reference), ZnO nanorods, Ag nanoparticles and hybrid ZnO-NR and Ag NP.

Figure 7.

Local I-V characteristic of metallic disc (reference), ZnO nanorods, Ag nanoparticles and hybrid ZnO-NR and Ag NP.

Figure 8.

The absorption spectrum of ZnO nanorods, Ag nanoparticles and hybrid ZnO-NR and Ag NP., inset Figure:(αℎυ)1/2 vs. Photon energy of ZnO nanorods, Ag nanoparticles and hybrid ZnO-NR and Ag NP.

Figure 8.

The absorption spectrum of ZnO nanorods, Ag nanoparticles and hybrid ZnO-NR and Ag NP., inset Figure:(αℎυ)1/2 vs. Photon energy of ZnO nanorods, Ag nanoparticles and hybrid ZnO-NR and Ag NP.

Figure 9.

The Photoluminescence spectrum o of ZnO nanorods, Ag nanoparticles and hybrid ZnO-NR and Ag NP.

Figure 9.

The Photoluminescence spectrum o of ZnO nanorods, Ag nanoparticles and hybrid ZnO-NR and Ag NP.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).