Introduction

Knowledge of the ichthyological biodiversity of African rivers and water bodies is a key matter for scientists and development managers (Daget et al., 1988; Lévêque, 1994; Lalèyè, 1995). Understanding the value chain (VC) provides policy-makers and fishing company managers with a systematic tool for understanding the various sector/company processes, and in particular the costs associated with the different stages of this value chain. By understanding the value chain, from catching a fish to the customer, the sustainable revenue growth is ensured (D.Russell and S.Hanoomanjee, 2012). The VC is a series of required activities that takes a product or service from its creation to marketing towards the end consumer (Kaplinsky and Morris, 2001, Masirika et al., 2020). The fisheries resources of the Congo Basin and particularly those of the Central African Republic (CAR) have not been significantly studied (Moelants, 2015; Harrison et al., 2016; Mukabo et al., 2020). Artisanal fishing supports millions of people worldwide, but it is often informal. As the contribution of artisanal fishing to socio-economic development is undervalued, its stakeholders (fishermen, fish mongers, etc.) often lack the authority and ability to participate in the decision-making process (WorldFish, 2021; Tshimuanga, 2022). The ecosystem services perspective is an anthropocentric approach that links biodiversity conservation to local socio-economic development (Mormont M., 2012; Tshimuanga, 2021). Freshwater fish is one of the resources exploited intensively in the Bamingui-Bangoran and Manovo Gounda St Floris parks, and hardly allows for sustainable exploitation of fishery resources. Freshwater fish production statistics are unknown to the Ministry of Fisheries. The species of freshwater fish in Bamingui-Bangoran and Manovo Gounda St Floris national parks have yet to be fully identified. Fishermen catch large numbers of adults just before reproduction and juveniles before they return to the river (Micha et al., 2022). This practice has harmful consequences for the fish value chain, as the quality of the fish (size and weight) influences the market price and puts certain players at a disadvantage (Rapport Enquête Cadre, WCS, 2022). At the local markets of Bamingui, Bangoran, Koukourou and Ndélé, smoked fish is most often found. Resellers do not bring sufficient quantities of fresh fish to market, due to a lack of conservation facilities. For better management and development of these fishery resources, it is important to study this value chain. The study consisted of: (1) studying the ichthyological biodiversity of the southern tributaries (basin heads) of the central Chari basin; (2) carrying out a functional analysis of the fish value chain in this zone.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Zone of Study

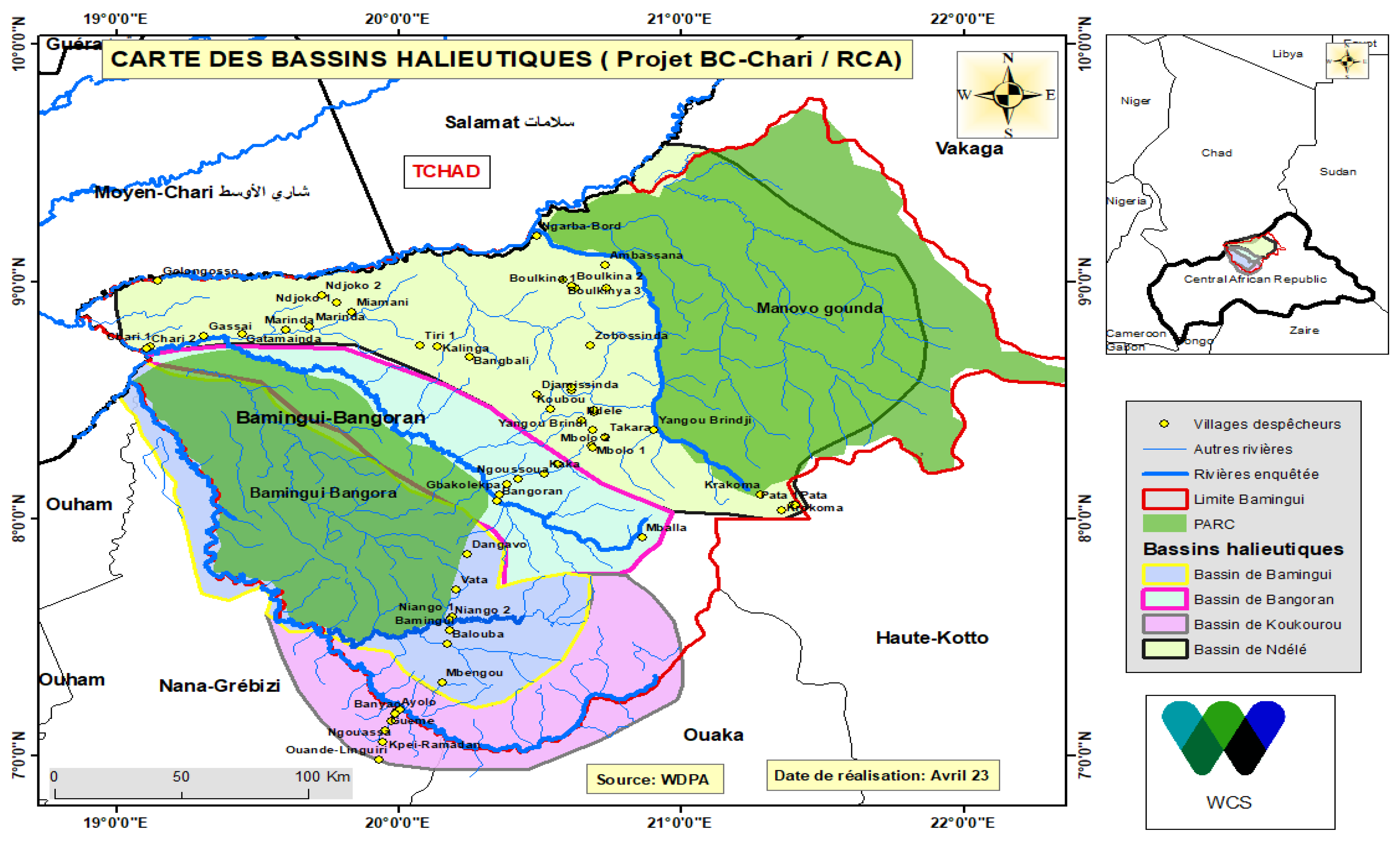

The study was carried out in the fishery basins of Bamingui, Bangoran, Koukourou and Ndélé, in the commune of Vassako and its villages: Koukourou, Balouba, Bamingui, Niango, Vata, Dangavo, Bakolekpa, Kovongo Mia, Bangoran, Kaka and Ndélé, and partly in the Protected Area Complex of the northeastern Central African Republic and their functionnal landscape (CAP-Nord-Est) covering an area of 115.716 km², or around 17% of the country's total surface area (

Figure 1).

Methods

To achieve the objectives formulated in this study, various methods, both qualitative and quantitative, were used. These methods were combined with other techniques such as survey questionnaires, direct interviews, focus groups and direct observations. The non-probability purposive sampling method was used to sample 250 stakeholders in 12 villages in the 4 fishing basins of the BBKN, namely Koukourou, Balouba, Bamingui, Niango, Vata, Dangavo, Bakolekpa, Kovongo Mia, Bangoran, Kaka, N'délé and Manovo.

VC4AD Method

The VC4AD (Value Chain for Development Analysis) method is a tool funded by the European Commission and implemented in partnership with AGRINATURA for the European Commission (FAO, 2021). It highlights the functional analysis of the value chain as objective 2 of the present study, which in turn highlights the economic, social and environmental analysis of the value chain.

Data Collection

Interviews with Stakeholders

Interviews with fishermen, fish traders, fishing input suppliers, restaurateurs and consumers took place during February and March 2023. These exchanges enabled us to describe them and define their roles in fish production and marketing.

Focus Group

The focus group with fishermen provided information on the techniques used for fishing, the equipment used and the fishing calendar.

Direct Observations

Observations at fishing sites and markets enabled us to describe the production, processing and marketing of fish in the fishery basins.

Fish Identification Keys

The Fish base (Froese, Pauly. 2019) and the identification keys of Blache et alii, 1964, Lévêque et al. (1990) and Stiassny et al. (2007) were used to identify the fish.

Results

Fish Biodiversity of the Bamingui, Bangoran and N’délé Basin

Our descent into the fishery basins of Bamingui-Bangoran, Koukourou and Ndélé enabled us to identify the fish encountered and cited by the fishermen themselves. This involved identifying the family, genus and scientific name of the fish (

Table 1).

The table above shows the names of the fish identified in the hands of fishermen and their distribution across the 4 fishery basins. These fish are the most commercialized in the value chain.

Functional Analysis of the Fish Value Chain

Description of Stakeholders and Their Roles in the Fish Value Chain

BBKN's fish value chain comprises two (2) main categories of stakeholders. Some are primary actors (fishermen, fishmongers, retailers, fishing input suppliers, restaurateurs and consumers) and others are secondary (government services).

Fishermen

The majority of fishermen are located in the Ndélé basin. These fishermen are mainly made up of the following ethnic groups: Rounga, Goula, Sara, Haoussa, Banda. The Bamingui, Bangoran and Koukourou basins are mainly made up of the Banda ethnic group. Some are permanent residents at the fishing sites, while others are temporary, depending on the fishing season. Fishermen say that they don't have the packaging needed to bring fish in good condition from the fishing basins to local markets, and that this is a disadvantage for them. To avoid transport losses, they sell the fish at low prices, which is profitable for fishmongers and retailers. From the point of view of WCS's management of the park's fishing zones, they feel that "invading the protected areas of the Bamingui-Bangoran and Manovo Gounda St Floris parks to fish is a right, because if the NGO WCS deprives us of this right, it should have found us alternative activities".

Fishmongers

Fishmongers play an important role in the fish value chain. They are responsible for distributing fish to local and national markets. Fish selling is primarily reserved for women, but some men also participate. Fishmongers have a very close relationship with fishermen. They can provide them with fishing equipment in exchange for a few baskets of fish. The fishmongers travel on motorcycles to help distribute the fish from Akoursoulbak and Ngarmba to Ndélé, then from Ndélé to Bamingui, Mbré or Bandoro. Despite their high incomes, fishmongers say they take a lot of losses through poor sales, due to the poor quality of the fish supplied by fishermen.

Retailers

Retail is carried out by wholesalers and retailers. They sell smoked fish in Ndélé, Bamingui, Bangoran and the capital, Bangui. Most resellers are Muslim women from the town of Ndélé. Sales of smoked fish are made in bulk in tubs, commonly called "n'gawi", or in cardboard boxes. Where preservation isn't possible, retailers engage more in the smoked fish trade than in fresh fish. Retailers say they have difficulty reselling smoked fish because of its small size and poor quality, due to the smoking technique. As a result, they lose money through poor sales. Others have no packaging to sell the fish on the market.

Restaurateurs

Fresh, smoked fish is a major source of savings for restaurateurs. Fish can be found in restaurants in Ndélé and Bamingui. Menus consists of both fresh and smoked fish. Fresh fish dishes are not available every day. Availability varies, depending on the fishing season and consumer demand. Restaurateurs report that fresh fish is expensive on local markets.

Consumers

Fish is an essential source of protein for consumers in Bamingui, Bangoran, Koukourou and Ndélé. Potential consumers include government officials, NGOs and travelers. Some consumers like the taste of the fish, but find the prices rather high. Others find the fish cheaper, but the sizes are too small for good consumption. For good consumption, fishermen should avoid catching small fish, say some consumers.

Secondary Players in the Fish Value Chain

BBKN's fish value chain is neglected by secondary actors (water and forestry agents). Fish production statistics are unknown to the Ministry of Water and Forests.

Governance and Participation of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) in the Fish Value Chain

The governance of the Bamingui-Bangoran and Manovo Gounda St Floris national parks and their fishing basins is ensured by the NGO WCS in partnership with the Central African government. WCS-CAR plays an extremely important role in the fish value chain of Bamingui, Bangoran, Koukourou and Ndélé. In the past, the fish value chain in BBKN was disorganized, but now, thanks to the ongoing work of WCS since 2018, there has been a lot of progress in the management of fisheries resources. Through the BC Chari project, which aims to support fishing communities through sustainable fishing, WCS currently supports 132 fishermen's groups recognized by local authorities. The trend is evolving to include fishmongers and fish traders. A sustainable fisheries management plan has been drawn up by WCS and its consultants, approved by a steering committee and validated by the fishermen at a general assembly. WCS-CAR continues to work to ensure that the Management Plan is respected by all stakeholders.

Features of Fishing Techniques

In the Bamingui-Bangoran, Koukourou and Ndélé basins, fishing is either active or passive, depending on the technique used. It should be noted that fishing is both individual and collective. Fish are caught using traditional methods (gillnets, hawk nets, longlines, harpoons, pots, knives, machetes and canoes). They are caught in two seasons: the favorable season (February to May) and the less favorable season (November to January).

Production

During the favorable season, Catch Per Unit Effort (CPUE) is 17 kg/day, or 510 kg/month. This compares with 4 kg/day, or 120 kg/month during the less favorable season.

Processing

Caught fish undergo three types of processing: smoking, drying and frying. Drying is used less by processors, as consumers do not appreciate its quality. Frying is also used less frequently, due to the high cost of cooking oil. Smoking, on the other hand, is the method most used by processors, as it is easier to use and requires no financial resources.

Conservation

Traders (wholesalers or retailers) have no freezers to keep fresh fish in good condition for several weeks, nor packaging (coolers) to pack fish in hygienic conditions. Instead, fish are stored and packaged in cardboard boxes and/or baskets, which lead to enormous losses sometimes.

Fish Marketing Channels

There are two key players in the marketing circuit (

Figure 2): fishmongers and transporters. They operate in two commercial circuits: the local circuit, where the product is transported to local markets, and the external circuit, where the product is transported to urban markets.

Economic Analysis

The average price of a cardboard carton of smoked fish in the Ndélé basin is around 40,000 FCFA for the fisherman, i.e. 1,212 FCFA/kg, 50,000 FCFA for the fishmonger, 55,000 FCFA for the wholesaler, 60,000 FCFA for the retailer and 90,000 FCFA to 100,000 FCFA, i.e. 2,727 to 3,030 FCFA/kg for the consumer. Considering the same situation in the Bamingui, Bangoran and Koukourou basins, smoked fish is sold in baskets with an average price of at least 20,000 FCFA, i.e. 1,428 FCFA/kg for the fisherman, 25,000 FCFA for the fishmonger, 30,000 FCFA for the wholesaler, 35,000 FCFA for the retailer and 40,000 FCFA to 50,000 FCFA, i.e. 2,857 to 3,571 FCFA/kg for the consumer. For fresh fish, we considered the same average price for 1 kg of fish across all the BBKN fishing basins, which is at least 500 FCFA for the fisherman, 800 FCFA for the fishmonger, 1,000 FCFA for the wholesaler, 1,200 FCFA for the retailer and 2,000 FCFA for the consumer. The results relating to investments in required fishing equipment per fisherman indicate that it lasts about one year. The annual depreciation of investments per fisherman amounts to 192,600 CFA francs, and their net operating income to 3,507,400 CFA francs.

Table 2.

Operating costs of fishermen in the fishing basins of NE CAR.

Table 2.

Operating costs of fishermen in the fishing basins of NE CAR.

| Indicators |

Period(months) |

Quantity (kg/unit/month) |

Unit price (FCFA/unit) |

Annual total (FCFA) |

| Production |

|

|

|

|

| Catch per year for fresh fish |

12 |

226 |

500 |

1 356 000 |

| Annual catch of processed smoked and dried fish |

12 |

630 |

400 |

3 024 000 |

| Production value |

|

|

|

4 380 000 |

| Wooden canoe without motor |

|

1 |

105 000 |

105 000 |

| Beach seine |

|

|

|

0 |

| Gillnets |

|

3 |

22 000 |

66 000 |

| Pots and traps |

|

530 |

800 |

424 000 |

| Machetes/knives |

|

4 |

5 000 |

20 000 |

| Transport |

|

|

|

0 |

| Fishing permits |

|

|

|

0 |

| Water rights |

|

|

|

0 |

| Food |

12 |

1 |

40 000 |

40 000 |

| Health |

|

1 |

25 000 |

25 000 |

| Fishing helper wages |

|

|

|

0 |

| Total costs |

|

|

|

680 000 |

| Depreciation |

|

|

|

|

| Wooden canoe without motor |

60 |

1 |

17 50 |

105 000 |

| Pots and traps |

12 |

530 |

800 |

9 600 |

| Beach seine |

|

|

|

0 |

| Gillnets |

3 |

3 |

20 000 |

60 000 |

| Machetes/knives |

36 |

3 |

500 |

18 000 |

| Total depreciation |

|

|

|

192 600 |

| Net operating income |

|

|

|

3 507 400 |

The operating costs of fishermen in the BBKN fishing basins includes revenues and costs, such as the purchase of dugout canoes, nets, etc., and costs involving depreciation.

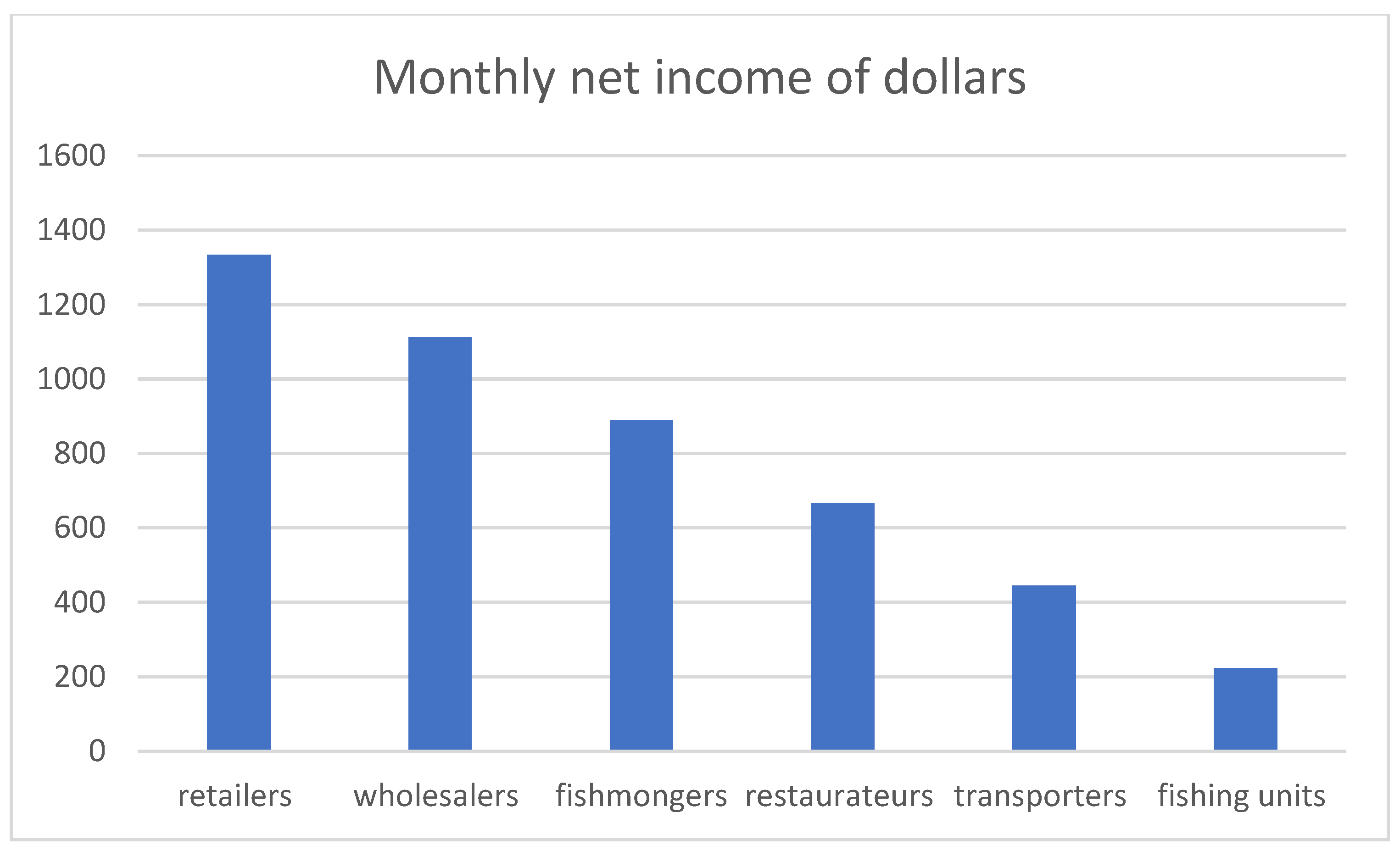

The economic profitability of the various players in the fish value chain in Bamingui, Bangoran, Koukourou and Ndele (

Figure 3) is as follows: retailers have a net monthly income of 1334

$, wholesalers 1112

$, fishmongers 889

$, restaurateurs 667

$, transporters 445

$ and fishing units 223

$. The low net monthly income of fishermen is explained by their dependence on fishmongers and suppliers of fishing inputs, but it also depends on the quality of the fish caught, which are most often bought by fishmongers at low prices. In fact, most fishermen are in debt because they receive their fishing inputs from suppliers and fishmongers.

Social Analysis of the Fish Value Chain

In order to verify that the value chain is socially sustainable, various aspects were examined:

Working Conditions

Working conditions in the fish value chain in BBKN's catchment areas do not appear to be very good for all concerned, and do not comply with the national labor code. Employment contracts are verbal, and the fishermen (men, women and children) are not safe as they have neither protective equipment (e.g. no life jackets) nor adequate materials to store and supply fish in hygienic conditions. They are at risk from drowning, attacks by hippos and crocodiles, snake bites, injuries caused by oyster shells or the spines of certain fish (Synodontis, etc.), bee stings and attacks by magnan ants. Women and children working in this value chain are subjected to difficult tasks such as fishing, processing and transporting fish, and receive very low wages. The actors are not properly structured. Working conditions will only be improved if the NGO WCS facilitates a proper structure for the various actors and provides them with adequate equipment for all the work along the value chain.

Water and Land Rights

Customary rights over the use of fishery resources do not exist, and value chain actors pay no fees to local authorities. Access to fishing sites is not based on the issuance of a fishing permit, nor does it comply with CAR's fishing code. The only actor involved in the governance of fishery resources in the Bamingui, Bangoran, Koukourou and Ndélé basins is the NGO WCS. This is why fishing is forbidden to fishermen in the protected areas of the Bamingui, Bangoran and Manovo parks, in accordance with the wildlife code, pending the development of a new fisheries management plan by the NGO WCS. To this end, fishermen are only allowed access to fishing in village hunting zones (ZCV).

Gender Equality

Access to fishing sites is open to both men and women, regardless of gender. At the organizational level and throughout the value chain, women are heavily involved in marketing, but have lower incomes when it comes to profit-sharing. Outside value chain activities, women have other demanding tasks, such as farming and housework. The NGO WCS must place particular emphasis on the creation of womens associations for fishmongers and traders to empower them and improve their incomes.

Food and Nutritional Conditions

In the Bamingui, Bangoran and Ndélé basins, value chain products (smoked and fresh fish) are an important source of animal protein for the population. Fish are available almost year-round.

Social Capital

We found that social capital is weak all along the value chain. Actors never receive subsidies or credits.

Household Living Conditions

The activities of the various links in the value chain do not contribute to improving living conditions. Stakeholders invest little in access to health, education, training, housing, water and sanitation infrastructures and services. In other words, fishermen and their organizations lack the financial means to access all these essential goods.

Environmental Analysis

In the BBKN fish basins, we noted habitat destruction (aquatic plants, riparian shrubs, spawning grounds). At fishing sites, fishing is destructive, resulting in the capture of small fish with very small-mesh nets (

Figure 4). In addition, bush fires are frequent, destroying riparian zones often used as spawning grounds or shelter for fry (nurseries). Deforestation through the cutting of wood for smoking fish and the construction of dugout canoes is recurrent at fishing sites. The slash-and-burn agriculture practiced by some fishermen leads to the degradation of forest ecosystems. The use of natural or artificial chemicals by fishermen not only kills all fish, including larvae and fry, but also their main food source, aquatic macro-invertebrates. Finally, the smoking technique has an impact on the environment and on human health, notably through the production of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHc).

SWOT analysis of the fish value chain in BBKN fisheries basins

| Strenghts |

Weaknesses |

Huge hydrographic network;

High ichthyological biodiversity;

High human potential;

Existance of protected areas. |

Low level of organization of actors;

Marginalization of certain actors;

Insufficient local markets;

Lack of electricity;

Lack of training;

Lack of credit;

Lack of fish storage facilities;

Lack of fish smoking techniques;

Low level of enforcement of laws and regulations;

Lack of knowledge of fishing legislation, poor governance;

Low level of fishermen's knowledge of how to protect fishery resources. |

| Opportunities |

Threats |

Possibility of co-management with park managers;

Sport fishing;

Tourism;

Possibility of exchanges with neighboring Chad and Sudan;

High accessibility. |

Insecurity at fishing sites;

Insecurity in some park areas;

Presence of transhumant herders;

Attacks by hippos and crocodiles;

Risk of drowning;

Risk of disease (dracunculiasis, malaria, etc.). |

Discussion

Ichthyological Biodiversity

The specific richness of the Bamingui, Bangoran, Koukourou and Ndélé fishing basins identified through this study is 18 families, 43 genus and 43 species, confirming the hypothesis that the ichthyological biodiversity of the BBKN fishing basins is diversified. However, Breuil (1996) estimated the fish biodiversity of the Bamingui, Bangoran, Koukourou and Ndélé fishing basins at 195 species belonging to 27 families, without any experimental fishing or collection. These studies need to be further developed in order to gather new data on the fish fauna through a program of experimental fishing and collection of the specimens caught, which will be carried out by WCS-RCA with the support of the JRS Biodiversiy Foundation.

Characteristics of Fishing Techniques

In the BBKN fishing basins, we noted a great diversity of fishing techniques, with different gear being used. The fishing gear identified and most commonly used by local communities are: gillnets, hawk nets, longlines, harpoons, pots, knives, machetes and dugout canoes. Soap, earthworms and small fish are the bait most commonly used by fishermen. In the Bangoran fishing basin, very few fishermen use dugout canoes and hawksbill nets, as their waterways are impassable (almost dry) from March onwards. This is the case for fishermen in the villages of Vata, Bangoran, Dangavo and Bakolepka, who use only gillnets, longlines, pots and spears. In a similar study carried out in the Mbali River community forest, Mwanandeke (2022) identified several fishing techniques, focusing on the scooping technique, which is practised in groups and only by women (young or adult), as well as fishing with impregnated mosquito nets “épuisettes”. Unlike other fishing techniques (gillnets, longlines, harpoons, pots, knives, machetes), scoop fishing and impregnated nets are causing a real problem for fish fauna and their habitats. This study shows that a variety of fishing techniques are practised according to local knowledge, but that these are not always wise or appropriate. It therefore seems necessary for the future that WCS-RCA :

Provide fishing communities with adequate fishing equipment to ensure sustainable fishing;

Reinforce fishermen's knowledge of good fishing practices;

Reinforce processors' knowledge of good practices for smoking fish in the Chorkor oven;

Review the delimitation of fishing zones;

Delimit spawning areas and set up defenses with the support of fishermen;

Set up a fishing statistics program (CPUE);

Support organizations of fishmongers, retailers and input traders to improve collaboration;

Encourage fishermen to adopt sustainable fishing practices through the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fishing, etc;

Ensure that the laws governing fisheries management in the Central African Republic are revised and enforced.

Destruction of Fish Biodiversity in BBKN Fishing Basins

The ichthyological biodiversity of the BBKN fish basins has not yet been studied in depth. Fishermen have no knowledge of spawning grounds or fish reproduction periods. They catch large numbers of adults just before spawning and juveniles before they return to the river, which is a mismanagement from a biological point of view and contributes to reducing and depleting subsequent catches. Biodiversity is therefore being destroyed in the rivers and streams of BBKN's fishing basins, as the number of fishermen and their fishing gear increases at an exponential rate. Hence the need to structure them, organize them and get them to adjust course towards a Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) and a co-management approach.

Sustainability of the BBKN Fish Value Chain

As for the sustainability of the fish value chain, it has to be said that it is not sustainable from a social point of view, which translates into precarious working conditions. Conflicts over land are recurrent between fishermen and livestock breeders because their cattle come to drink in the rivers of these fishing basins and consequently impact fishing activities by destroying nets and traps. There is also a gender imbalance, as women work more than men but are paid less. The net monthly income of actors in the fish value chain is poorly distributed, as the main players in fish production receive a much lower net monthly income than secondary players. Food and nutritional conditions are hygienically inadequate, as fish is collected, processed and distributed in very precarious conditions. In fact, smoked fish distributed along this value chain leaves much to be desired due to its poor quality (carbonized), proof that fish processors do not know how to smoke fish properly, hence the need to strengthen their capacities in this area. Lastly, social capital is insignificant for all players, as the activities of this fish value chain generate little income, which means they cannot access essential goods. Nor is it environmentally sustainable, as the biodiversity of BBKN fish basins is threatened by overexploitation, destructive practices (nylon gillnets, small-mesh nets, assagaies, poisons, etc.) and fishing in spawning grounds. All these problems persist due to a lack of respect for fishing regulations. And finally, it is not sustainable from an economic point of view, as the incomes of the main players are low, particularly those of the fishermen. To all this, we must add the insecurity that is in full swing in the area, affecting the fish trade.

Model Strategy for Value Chain Development

In view of the many challenges facing the BBKN fish value chain, the following model is proposed for its improvement:

Structuring of VC players (fishermen, fishmongers and traders);

Creation of agro-piscicultural sites to enhance the value of the most commercialized fish species, not only to increase the income of stakeholders, but also to limit their access to prohibited areas to maintain fish stocks;

Improved living conditions for stakeholders (medical care, access to education, drinking water, etc.) through subsidies (micro-credits);

Capacity-building for fishermen, with the adoption of chorkor ovens to improve fish smoking techniques;

Raising fishermen's awareness of proper fishing techniques to supply mature fish to all players in the value chain to improve their incomes;

Implement a co-management approach to fisheries resources between WCS and stakeholders.

Conclusion

The freshwater fish species in Bamingui-Bangoran and Manovo Gounda St Floris national parks have not yet been fully identified. Through this study, 18 families and 43 species of fish caught by fishermen have been identified. The Central Chari Basin is home to several protected areas, including the Zakouma Park in Chad, the Siniaka Minia Faunal Reserve, the Barh Aouk and Barh Salamat, and the North-East Protected Areas Complex (CAP-NE) in CAR, including the Bamingui-Bangoran National Park and the Manovo-Gounda Saint Floris Park. Artisanal freshwater fishing contributes to poverty reduction in the Bamingui, Bangoran, Koukourou and Manovo areas through the income it generates, but fishermen do not hesitate to enter these protected areas in order to take wood for smoking fish, and to fish in these areas, which are mostly off-limits and constitute breeding grounds for fishery resources, nurseries, contributing to the replenishment of fish stocks, and which, through their migrations, replenish the ordinary areas (outside parks) authorized for catches during the high-water season. This practice, which runs counter to the objective of conserving protected areas, also constitutes a danger for the fish value chain. The fish industry in Bamingui-Bangoran, Koukourou and Ndélé seems neglected and unstructured. Each player is trying to make the most of his or her position. We have seen that the net monthly income of fishermen is significantly lower than that of others, and that they are the real producers behind fish distribution. There is therefore a need to improve their incomes by adopting the Maximum Balanced Yield and raising awareness of sustainable fishing, with the aim of getting them to participate in the protection and conservation of their resources by refraining from fishing in these protected areas. Finally, our study shows that a Sustainable Fishing Development and Management Plan needs to be put in place, including a substantial technical and financial support program that will enable the creation of training structures in the fishing industry and the strengthening of their associations to raise the level of knowledge of the fishermen but also and above all, via schools, that of their children who are for the most part future fishermen.

Acknowledgments

First of all, the authors would like to thank our main partners and financial backers, namely AGRINATURA and the European Union, for bearing the costs of our training for a Professional Master's degree in Protected Area Management at ERAIFT during the years 2021 to 2023. We would also like to thank UNESCO, the University of Liège and Gembloux (Belgium) and the University of Namur (Belgium), in particular Professor Jean-Claude MICHA, for their teaching and technical assistance in our training course. We would also like to thank the academic authorities at ERAIFT, notably Director Baudouin MICHEL and Academic and Research Secretary Jean-Pierre MATE MWERU, at the Ecole de Faune in Garoua, the members of the WCS-RCA project, notably Country Director M. TWAGUIRASHYAKA Felin, the BC-Chari Landscape Manager, Mr. ONDOUA ONDOUA Gervais, Jenica Betsh, the actors of the Fish Value Chain of the Bamingui, Bangoran, Koukourou and Ndélé Basins for their good will and support in the realization of this study.

Authors’ contributions

Contributed by: The article is written by Gbagalama.

Data acquisition

Field data acquisition is done by Gbagalama (1st author).

Data analysis and interpretation

Data analysis and interpretation by Gbagalama.

Correction and revision of the article

The correction and revision of the article were carried out by Professor Micha, teacher-researcher Samba and cross-border expert Ndakobo.

Validation of the article

the final version of the article was approved and validated by Professor Micha. All the authors contributed equally to this work.

Project management

The Nature Conservancy Society (WCS-CAR) is responsible for project management.

Acquisition of funds

The field mission costs were allocated by the WCS-CAR project and the internship costs were borne by ERAIFT/UNESCO from Kinshasa.

Resources

Field materials and equipment were provided by WCS-CAR.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

-

BLACHE J. Les poissons du Bassin du TCHAD et du Bassin adjacent du Moyen Kebbi, 1964. 483 pages.

-

BREUIL, C., CACAUD P et NUGENT C. Contribution à la formulation des axes stratégiques de 1996 développement du secteur des pêches et de la pisciculture en République Centrafricaine. FAO/TCP/CAF/4451, 1996.

-

DAGET J., 1988. Systématique. In : Biologie et Ecologie des poissons d’eau douce africains (Lévêque C., Bruton MN. Et G.W. Sentongo, Eds), ORSTOM. Coll. Trav. Doc. Paris, 216: 15-34.

-

FAO (2018). La situation mondiale des pêches et de l’aquaculture 2018. Atteindre les ODD. Rome. Consulté sur https://www.fao.org/3/I9540FR/i9540fr. pdf.

-

FAO, 2021, VC4AD (Analyse de la Chaîne de Valeur du Développement) et FISH4ACP. Developing sustainable value chains for aquatic products a methodological brief for analysis and design Draft Document – September 202.

-

FROESE R, PAULY D. 2019. FishBase. Sur http://www.fishbase.org/search.php.

-

HARRISON IJ, BRUMMETT R, MELANIE L, STIASSNY J. 2016. The Congo River Basin. In the Wetland Book, Finlayson MC, Milton RG, prentice R C, Davidson NC (ed). Dordrecht : Springer Netherlands ; 1-18. [CrossRef]

-

KAPLINSKY R, MORRIS M. 2001. A handbook for value chain research. IDRC : Brighton.

-

LALEYE P., CHIKOU A., PHILIPPART JC., TEUGELS G., VANDEWALLE P. 1985. Etude de la diversité Ichtyologique du Bassin du Fleuve Ouémé au Bénin. 11 pages.

-

LEVEQUE C, PAUGY D, TEUGELS GG. 1994. Faune Des poissons d’eaux Douces et Saumâtres d’Afrique de l’Ouest. Editions de l’ORSTOM, Collection Faune Tropicale (n° : 28) : Tervuren, Belgique.

-

MASIRIKA J.M., MUKABO G.O, KASEREKA PK, JARIEKONG A, TULINABO GH, MICHA J.C, NTAKIMAZI G, NSHOMBO V.M. Etude par la chaîne de valeur de la filière d’exploitation de Bragrus Spp. dans la partie congolaise des Lacs Albert et Edouard, 2020. 18 pages.

-

MICHA JC., MANGHAR P., SAMBA F. (2022). Rapport d’identification de l’Etat des pêches dans le Bassin de Chari et Logone (RCA-Tchad) 2022.

-

MOELANTS T. 2015. Diversity and ecology of the ichthyofauna of the Middle and Upper Congo basin : a case-study in the region of the Wagenia falls (Democratic Republic of the Congo).

-

MORMONT, M. (2012). Services écosystémiques et développement rural : Propositions méthodologiques. Réseau wallon de Développement Rural, 21. Consulté sur https://www.reseaupwdr.be/sites/default/files/270514_121212_er_ servicesecosystemiquesetdeveloppementrural.pdf.

-

MWANANDEKE A.H., LUHUSU K.F., MONGHIEMO C., TSHIASHALA M.D., RIERA B., et MICHA J.C. (2022). Caractérisation de la pêche et utilisation des ressources halieutiques dans la forêt communautaire de la rivière Mbali (CFCL-RM) en province de Maï-Ndombe (RD Congo), Rev. Sci. Tech. For. Environ. Bassin Congo. Volume 19. P. 51-64, Octobre 2022 https://zenodo.org/record/7114240#.Y6qdS3bMJPY. [CrossRef]

-

NDAKOBO D., et MICHA J.C. (2022). Rapport Enquête Cadre de la pêche artisanale dans le Nord-Est de la République Centrafricaine. 37 pages.

-

RUSSELL D., HANOOMANJEE S. (2012). Guide sur l’analyse et la promotion de la Chaîne de Valeur financé par l’Union Européenne.

-

STIASSNY, M.L.J., TEUGELS, G.G. et HOPKINS, C.D. (2007). Poissons d’eaux douces et saumâtres de basse Guinée, ouest de l’Afrique centrale = The Fresh and Brackish Water Fishes of Lower Guinea, West-Central Africa, IRD Editions (Vol. 1), p. 806. https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/ed-06-08/010044384.pdf.

-

TSHIMUANGA K., BAUDOUIN M., LUHUSU K., MICHA J.C. (2022). Analyse Fonctionnelle de la Chaîne de Valeur de la crevette géante d’eau douce (Macrobrachium SP) du Parc Marin des Mongroves, 62 pages.

-

WORLDFISH (2021). Illuminating Hidden Harvests to shine a light on small-scale fisheries. Consulté sur https://www.worldfishcenter.org/blog/illuminatinghidden-harvests-shine-light-small-scale-fisheries.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).