Submitted:

30 July 2024

Posted:

31 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Perceived participation restrictions for people with SCI and their loved ones during COVID-19

3.1.1. Interruptions and changes in service provision.

3.1.2. Barriers and inconveniences

3.1.3. It’s better than nothing.

3.2. There was no change in life habits (but we found new ways to do some things)

3.2.1. Life simply continued as usual.

3.2.1. New pastimes and interests.

3.3. What does the future hold?

3.3.1. Concerns

3.3.2. Hopes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Government of Canada. COVID-19 and people with disabilities in Canada 2021 [Accessed on 9 June 2021]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/guidance-documents/people-with-disabilities.html#shr-pg0.

- Fortin-Bédard N, Lamontagne M-E, Ladry N-J, et al. Exploring the Experiences of People with Disabilities during the First Year of COVID-19 Restrictions in the Province of Quebec, Canada. Disabilities. 2023;3(1):12-27.

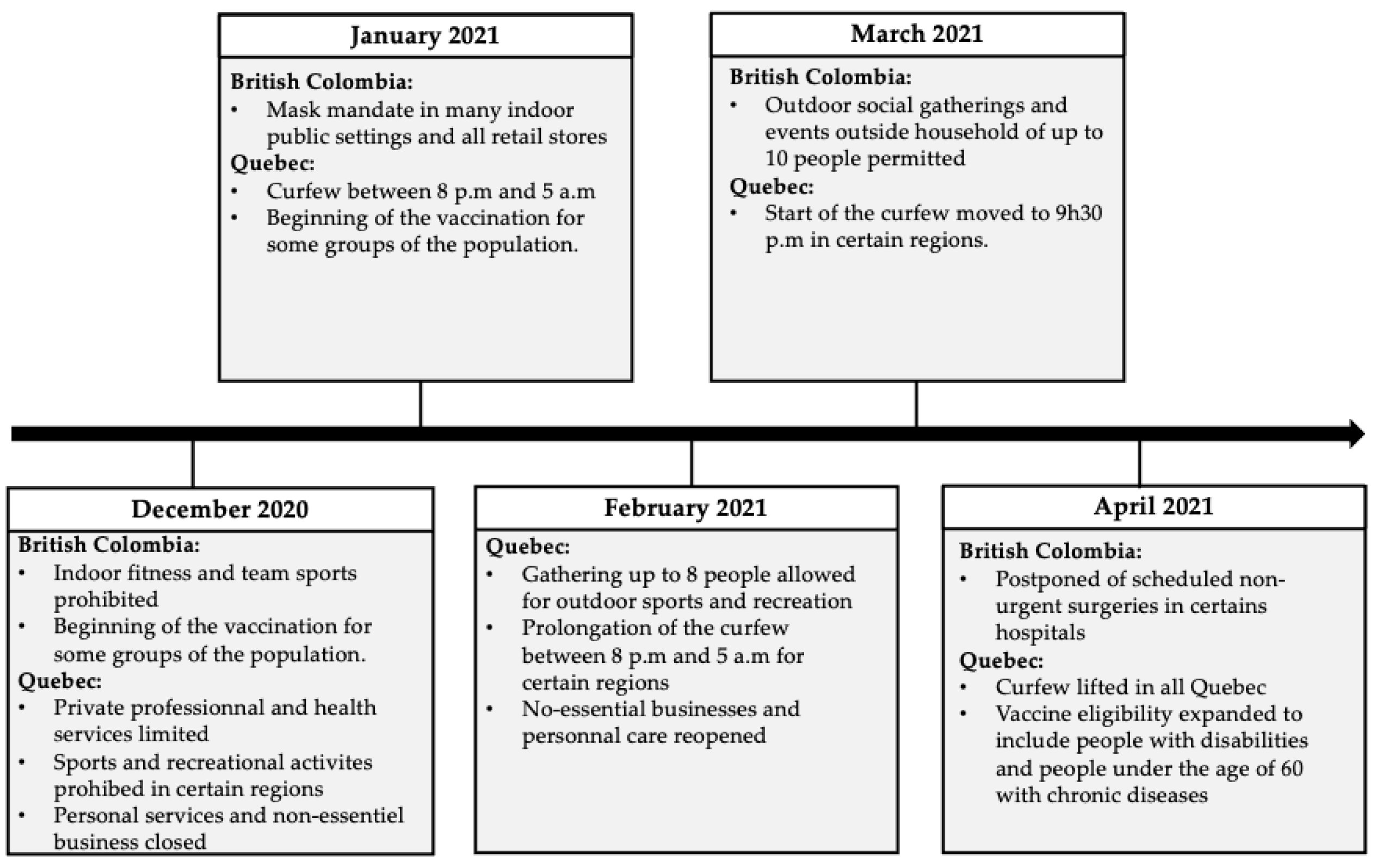

- Institut national de santé publique du Québec. Ligne du temps COVID-19 au Québec: Institut national de santé publique du Québec; 2021 [Accessed on 8 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees/ligne-du-temps.

- Lebrasseur A, Fortin-Bedard N, Lettre J, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on people with physical disabilities: A rapid review. Disability and Health Journal. 2021 Jan;14(1):101014.

- Di Stefano V, Battaglia G, Giustino V, et al. Significant reduction of physical activity in patients with neuromuscular disease during COVID-19 pandemic: the long-term consequences of quarantine. Journal of Neurology. 2021 Jan;268(1):20-26.

- Lopez-Sanchez GF, Lopez-Bueno R, Gil-Salmeron A, et al. Comparison of physical activity levels in Spanish adults with chronic conditions before and during COVID-19 quarantine. European Journal of Public Health. 2021 Feb 1;31(1):161-166.

- Capuano R, Altieri M, Bisecco A, et al. Psychological consequences of COVID-19 pandemic in Italian MS patients: signs of resilience? Journal of Neurology. 2021 Mar;268(3):743-750.

- Mesa Vieira C, Franco OH, Gómez Restrepo C, et al. COVID-19: The forgotten priorities of the pandemic. Maturitas. 2020 Jun;136:38-41.

- Marco-Ahulló A, Montesinos-Magraner L, González LM, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the self-reported physical activity of people with complete thoracic spinal cord injury full-time manual wheelchair users. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 2021 Jan 19:1-5.

- Stillman MD, Capron M, Alexander M, et al. COVID-19 and spinal cord injury and disease: results of an international survey. Spinal Cord Series and Cases. 2020 Apr 15;6(1):21.

- Gustafson K, Stillman M, Capron M, et al. COVID-19 and spinal cord injury and disease: results of an international survey as the pandemic progresses. Spinal Cord Series and Cases. 2021 2021/02/12;7(1):13.

- Buckingham SA, Anil K, Demain S, et al. Telerehabilitation for People With Physical Disabilities and Movement Impairment: A Survey of United Kingdom Practitioners. JMIRx Med. 2022 2022/1/3;3(1):e30516.

- Fortin-Bédard N, de Serres-Lafontaine A, Best KL, et al. Experiences of Social Participation for Canadian Wheelchair Users with Spinal Cord Injury during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Disabilities. 2022;2(3):398-414.

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2006;5(1):80-92.

- Best KL, Routhier F, Sweet SN, et al. The Smartphone Peer Physical Activity Counseling (SPPAC) Program for Manual Wheelchair Users: Protocol of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017 Apr 26;6(4):e69.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadian COVID-19 Intervention Timeline 2022 [Accessed on 9 June 2021]. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/canadian-covid-19-intervention-timeline.

- International Network on the Disability Creation Process. The Human Development Model – Disability Creation Process - Key Concepts 2021.[Accessed on 7 June 2021]. Available from: https://ripph.qc.ca/en/hdm-dcp-model/key-concepts/.

- Roberts K, Dowell A, Nie J-B. Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2019 2019/03/28;19(1):66.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo (released in March 2020) 2020. Available from: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, et al. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2017 2017/12/01;16(1):1609406917733847.

- Barclay L, McDonald R, Lentin P, et al. Facilitators and barriers to social and community participation following spinal cord injury. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2016 Feb;63(1):19-28.

- Munce SEP, Webster F, Fehlings MG, et al. Perceived facilitators and barriers to self-management in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Neurology. 2014 2014/03/13;14(1):48.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Disability considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak 2020 [Accessed on 8 July 2021]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/332015/WHO-2019-nCov-Disability-2020.1-eng.pdf.

- Huang J, Pacheco Barzallo D, Rubinelli S, et al. What influences the use of professional home care for individuals with spinal cord injury? A cross-sectional study on family caregivers. Spinal Cord. 2019 2019/11/01;57(11):924-932.

- Giusiano S, Peotta L, Iazzolino B, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis caregiver burden and patients’ quality of life during COVID-19 pandemic. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration. 2021:1-3.

- Jeyathevan G, Catharine Craven B, Cameron JI, et al. Facilitators and barriers to supporting individuals with spinal cord injury in the community: experiences of family caregivers and care recipients. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2020 Jun;42(13):1844-1854.

- Huang D, Siddiqui SA, Touchett HN, et al. Protecting the most vulnerable among us: Access to care and resources for persons with disability from spinal cord injury during the COVID-19 pandemic. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2021;13(6):632-636.

- Ammar A, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, et al. COVID-19 Home Confinement Negatively Impacts Social Participation and Life Satisfaction: A Worldwide Multicenter Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(17).

- Annaswamy TM, Verduzco-Gutierrez M, Frieden L. Telemedicine barriers and challenges for persons with disabilities: COVID-19 and beyond. Disabil Health J. 2020 Oct;13(4):100973.

- Selick A, Durbin J, Hamdani Y, et al. Accessibility of Virtual Primary Care for Adults With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative Study. JMIR Form Res. 2022 2022/8/22;6(8):e38916.

- Ripat JD, Brown CL, Ethans KD. Barriers to wheelchair use in the winter. The Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2015 Jun;96(6):1117-22.

- Andrews EE, Ayers KB, Brown KS, et al. No body is expendable: Medical rationing and disability justice during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychological Association; 2021. p. 451-461.

- Mikolajczyk B, Draganich C, Philippus A, et al. Resilience and mental health in individuals with spinal cord injury during the COVID-19 pandemic. Spinal Cord. 2021 2021/12/01;59(12):1261-1267.

- Desjeux, C. COVID-19 : handicaps, perte d’autonomie et aides humaines. Difficultés et tensions des gestes barrières et des équipements de protection individuelle à domicile. Alter. 2020 2020/09/01/;14(3):249-257.

- Cochran, AL. Impacts of COVID-19 on access to transportation for people with disabilities. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives. 2020 2020/11/01/;8:100263.

- Kilic SA, Dorstyn DS, Guiver NG. Examining factors that contribute to the process of resilience following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013 2013/07/01;51(7):553-557.

- Hammarberg K, Kirkman M, de Lacey S. Qualitative research methods: when to use them and how to judge them. Human Reproduction. 2016;31(3):498-501.

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| mean [SD] | |

| Age, years | 48.8 [15.1] |

| Time Using Any wheelchair, years | 15.1 [13.3] |

| n (%) | |

| Sex | |

| Women | 6 (33.3) |

| Men | 12 (66.7) |

| Province of Origin | |

| Quebec | 14 (77.8) |

| British Columbia | 4 (22.2) |

| Employment Status (n=17) | |

| Employed | 3 (17.6) |

| Unemployed | 9 (53.0) |

| Retired | 5 (29.4) |

| Highest Education Level | |

| High school (started) | 6 (33.3) |

| College/University (started) | 2 (11.1) |

| College/University (completed) | 7 (38.9) |

| Post-graduate studies | 2 (11.1) |

| Annual Household Income, $ (n=16) | |

| < 29’999 | 7 (43.7) |

| 30’000-44’999 | 3 (18.8) |

| 45’000-59’999 | 3 (18.8) |

| > 60’000 | 3 (18.8) |

| Diagnostic | |

| Paraplegic | 15 (83.3) |

| Tetraplegic | 3 (16.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).