Submitted:

01 August 2024

Posted:

02 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Study Intervention

2.3. Study Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

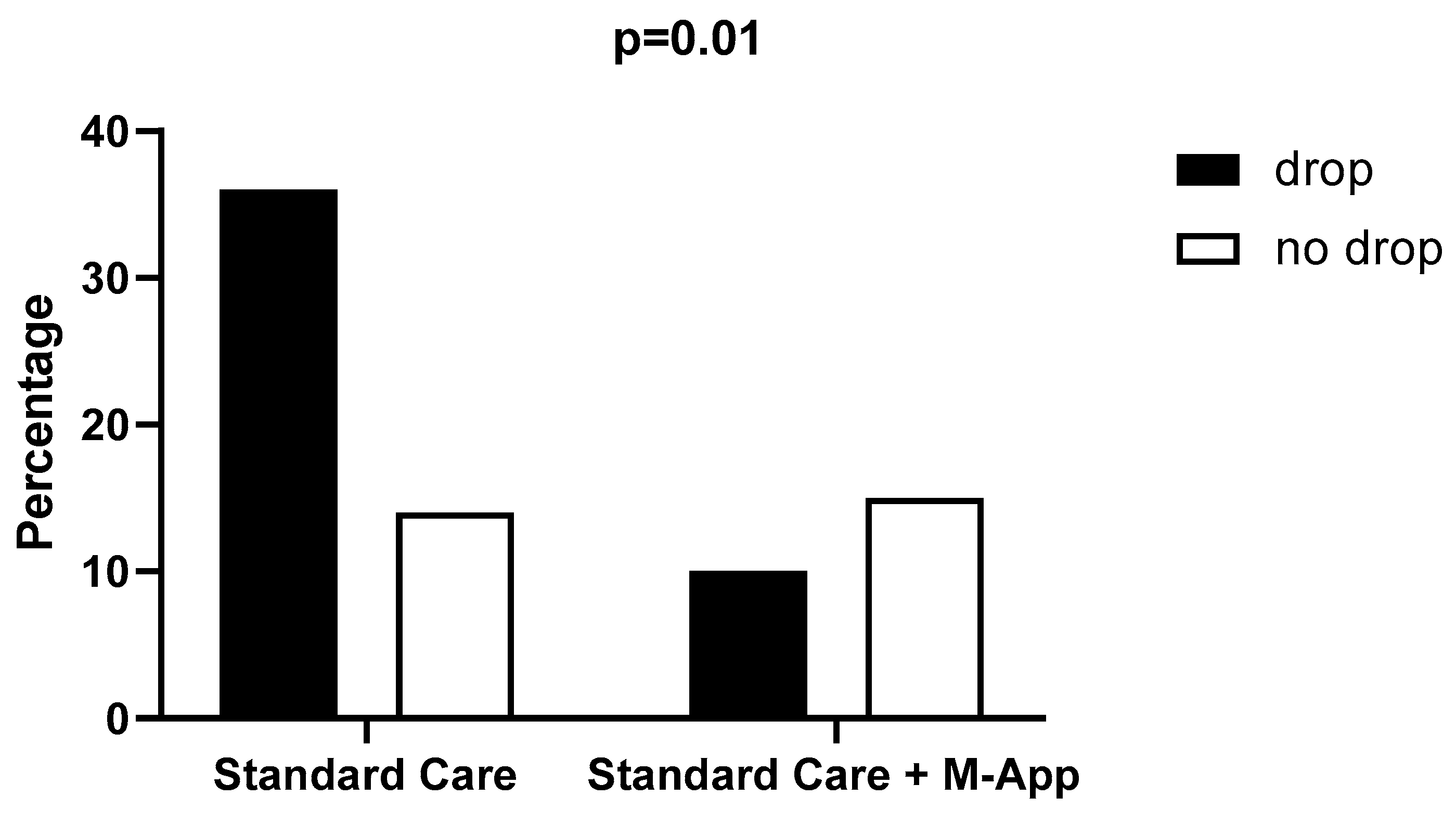

3.1. Drop out Assessment

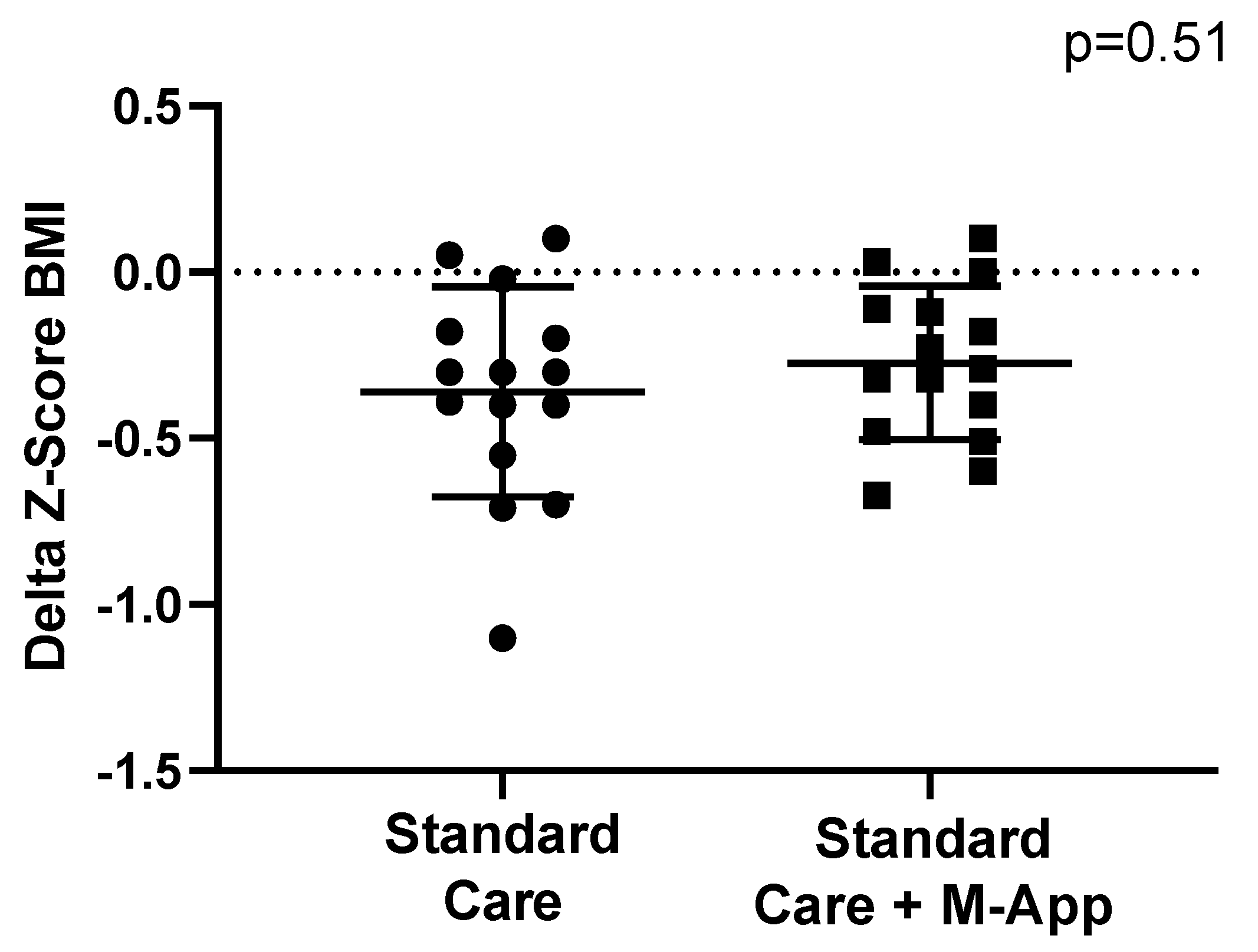

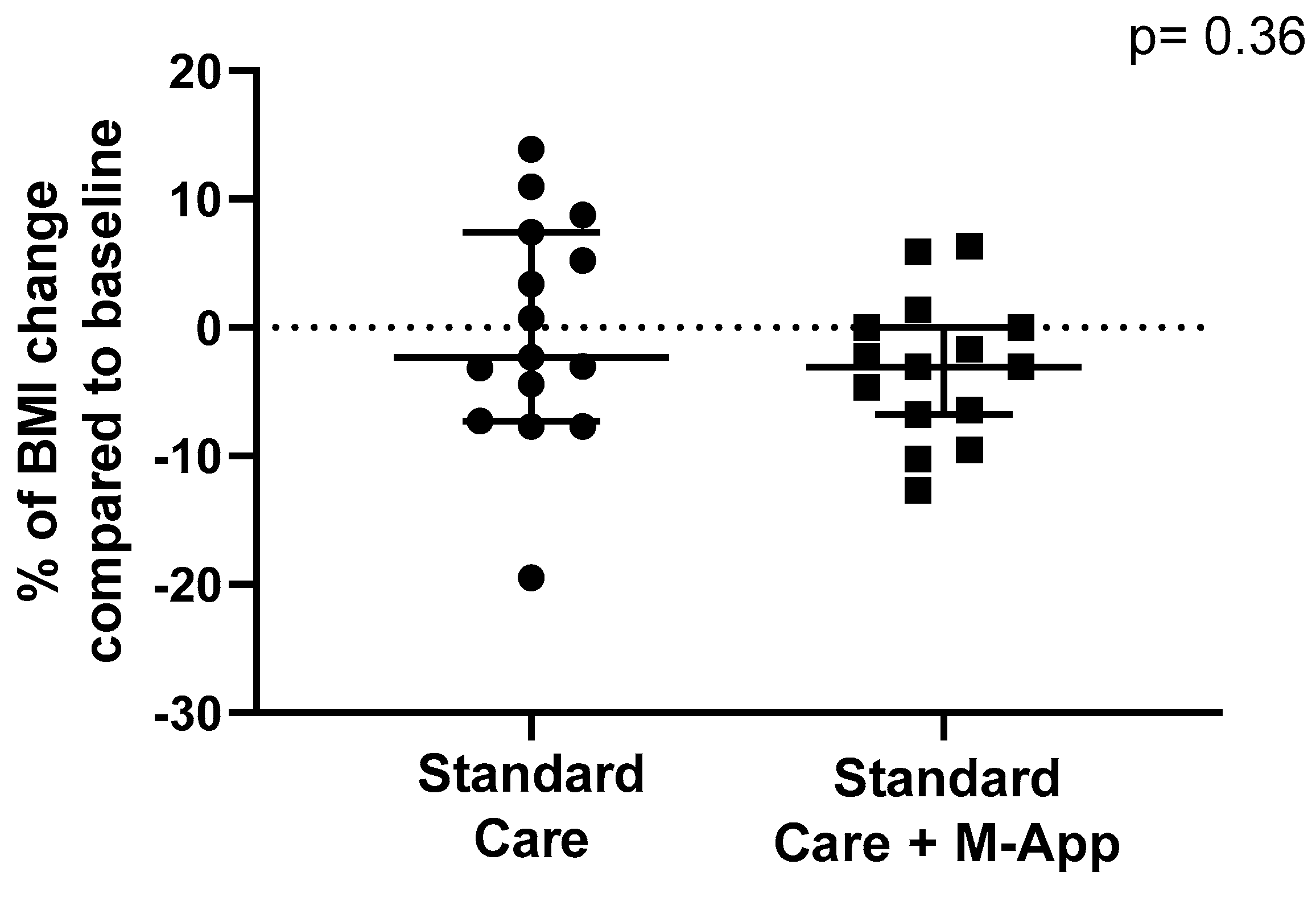

3.2. Weight-Loss Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jebeile, H.; Kelly, A.S.; O’Malley, G.; Baur, L.A. Obesity in children and adolescents: epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10(5):351-365. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 27 Jul 2024).

- Global Obesity Observatory. Available online: https://data.worldobesity.org/ (accessed on 27 Jul 2024).

- Nardone, P.; Ciardullo, S. Stato ponderale e stili di vita di bambine e bambini: i dati italiani della sorveglianza “OKkio alla SALUTE 2023” e il contributo dello studio “EPaS-ISS”, Roma (10 May 2024).

- Tiwari, A.; Balasundaram, P. Public Health Considerations Regarding Obesity. 2023 Jun 5. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 34283488.

- Marcus, C.; Danielsson, P.; Hagman, E. Pediatric obesity-Long-term consequences and effect of weight loss. J Intern Med. 2022; 292(6):870-891. [CrossRef]

- Friedemann, C.; Heneghan, C.; Mahtani, K.; Thompson, M.; Perera, R.; Ward, A.M. Cardiovascular disease risk in healthy children and its association with body mass index: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012; 345:e4759. [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.T.; Krenek, A.; Magge, S.N. Childhood Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2023; 25(7):405-415. [CrossRef]

- Umano, G.R.; Galderisi, A.; Aiello, F.; Martino, M.; Camponesco, O.; Di Sessa, A.; Marzuillo, P.; Alfonso, P.; Miraglia Del Giudice, E. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is associated with the impairment of beta-cell response to glucose in children and adolescents with obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2023 Apr;47(4):257-262. [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Ma, J.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, W. Association between overweight or obesity and the risk for childhood asthma and wheeze: an updated meta-analysis on 18 articles and 73252 children. Pediatr Obes 2019; 14: e12532. [CrossRef]

- Umano, G.R.; Rondinelli, G.; Luciano, M.; Pennarella, A.; Aiello, F.; Mangoni di Santo Stefano, G.S.R.C.; Di Sessa, A.; Marzuillo, P.; Papparella, A.; Miraglia Del Giudice, E. Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire Predicts Moderate-to-Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Children and Adolescents with Obesity. Children (Basel). 2022 Aug 27;9(9):1303. [CrossRef]

- Marzuillo, P.; Di Sessa, A.; Umano, G.R.; Nunziata, L.; Cirillo, G.; Perrone, L.; Miraglia Del Giudice, E.; Grandone, A. Novel association between the nonsynonymous A803G polymorphism of the N-acetyltransferase 2 gene and impaired glucose homeostasis in obese children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2017 Sep;18(6):478-484. [CrossRef]

- Santoro, N.; Amato, A. Grandone, A.; Brienza, C.; Savarese, P.; Tartaglione, N.; Marzuillo, P.; Perrone, L.; Miraglia Del Giudice, E. Predicting metabolic syndrome in obese children and adolescents: look, measure and ask. Obes Facts. 2013; 6(1):48-56. [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M.; Alkhouri, N.; Vajro, P.; Baumann, U.; Weiss, R.; Socha, P.; Marcus, C.; Lee, W.S.; Kelly, D.; Porta, G.; El-Guindi, M.A.; Alisi, A.; Mann, J.P.; Mouane, N.; Baur, L.A.; Dhawan, A.; George, J. Defining paediatric metabolic (dysfunction)-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 6: 864–73. [CrossRef]

- Maguolo, A.; Maffeis, C. Acanthosis nigricans in childhood: a cutaneous marker that should not be underestimated, especially in obese children. Acta Paediatr 2020; 109: 481–87. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Garcia, P.; Migueles, J.H., Cadenas-Sanc,0ez, C.; Esteban-Cornejo, I.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Plaza-Florido, A.; Vanrenterghem, J.; Ortega, F.B.; A systematic review on biomechanical characteristics of walking in children and adolescents with overweight/obesity: possible implications for the development of musculoskeletal disorders. Obes Rev 2019; 20: 1033–44. [CrossRef]

- Di Sessa, A.; Passaro, A.P. Colasante, A.M.; Cioffi, S.; Guarino, S.; Umano, G.R., Papparella, A.; Miraglia Del Giudice, E.; Marzuillo, P. Kidney damage predictors in children with metabolically healthy and metabolically unhealthy obesity phenotype. Int J Obes (Lond). 2023 Dec;47(12):1247-1255. [CrossRef]

- Mahumud, R.A.; Sahle, B.W.; Owusu-Addo, E.; Chen, W.; Morton, R.L.; Renzaho, A.M.N. Association of dietary intake, physical activity, and sedentary behaviours with overweight and obesity among 282,213 adolescents in 89 low and middle income to high-income countries. Int J Obes 2021; 45: 2404–18. [CrossRef]

- Liberali, R.; Kupek, E. Dietary patterns and childhood obesity risk: A systematic review. Child Obes 2020; 16: 70–85. [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Mu, M.; Liu, K.; He, Y. Screen time and childhood overweight/obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Care Health Dev 2019; 45: 744–53. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.N.; Banda, J.A.; Hale, L.; Lu, A.S.; Fleming-Milici, F.; Calvert, S.L.; Wartella E. Screen media exposure and obesity in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2017; 140 (suppl 2): S97–101. [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.; Martin, A.; Janssen, X.; Wilson, M.G.; Gibson, A,M.; Hughes, A.; Reilly, J.J. Longitudinal changes in moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2020; 21: e12953. [CrossRef]

- Felső, R.; Lohner, Hollódy, K.; Erhardt, É.; Molnár, D. S. Relationship between sleep duration and childhood obesity: systematic review including the potential underlying mechanisms. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2017; 27: 751–61. [CrossRef]

- Mihrshahi, S.; Baur, L.A. What exposures in early life are risk factors for childhood obesity? J Paediatr Child Health 2018; 54: 1294–98. [CrossRef]

- Woo Baidal, J.A.; Locks, L.M.; Cheng ER, Blake-Lamb TL, Perkins ME, Taveras EM. Risk factors for childhood obesity in the first 1,000 days: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2016; 50: 761–79. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.D.; Fu, E.; Kobayashi, M.A. Prevention and Management of Childhood Obesity and Its Psychological and Health Comorbidities. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2020 May; 16:351-378. [CrossRef]

- Maffeis, C.; Olivieri, F.; Valerio, G.; Verduci, E.; Licenziati, M.R.; Calcaterra, V; Pelizzo, G.; Salerno, M.; Staiano, A.; Bernasconi, S.; Buganza R, Crinò, A.; Corciulo, N.; Corica, D.; Destro, F., Di Bonito, P.; Di Pietro, M.; Di Sessa, A.; deSanctis, L.; Faienza, M.F.; Filannino, G.; Fintini, D.; Fornari, E.; Franceschi, R.; Franco, F.; Franzese, A.; Giusti, L.F.; Grugni, G.; Iafusco, D.; Iughetti, L.; Lera, R.; Limauro, R.; Maguolo, A.; Mancioppi, V.; Manco, M.; Del Giudice, E.M, Morandi, A.; Moro, B.; Mozzillo, E.; Rabbone, I.; Peverelli, P.; Predieri, B.; Purromuto, S.; Stagi, S.; Street, M.E.; Tanas, R.; Tornese, G.; Umano, G.R.; Wasniewska, M. The treatment of obesity in children and adolescents: consensus position statement of the Italian society of pediatric endocrinology and diabetology, Italian Society of Pediatrics and Italian Society of Pediatric Surgery. Ital J Pediatr. 2023;49(1):69. [CrossRef]

- Styne, D.M.; Arslanian, S.A.; Connor, E.L.; Farooqi, I.S.; Murad, M.H.; Silverstein, J.H.; Yanovski, J.A. Pediatric Obesity-Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017; 102(3):709-757. [CrossRef]

- Hampl, S.E.; Hassink, S.G.; Skinner, A.C.; Armstrong, S.C.; Barlow, S.E.; Bolling, C.F.; Avila Edwards, K.C.; Eneli, I.; Hamre, R.; Joseph, M.M.; Lunsford, D.; Mendonca, E.; Michalsky, M.P.; Mirza, N.; Ochoa, E.R.; Sharifi, M.; Staiano, A.E.; Weedn, A.E.; Flinn, S.K.; Lindros, J.; Okechukwu, K. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity. Pediatrics. 2023 Feb 1;151(2):e2022060640. Erratum in: Pediatrics. 2024 Jan 1;153(1):e2023064612. doi: 10.1542/peds.2023-064612. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.; Snoeck Henkemans, S.; van Teeffelen, J.; Kornelisse, K.; Bindels, P.J.E.; Koes, B.W.; van Middelkoop, M. Determinants of dropout and compliance of children participating in a multidisciplinary intervention programme for overweight and obesity in socially deprived areas. Fam. Pract. 2023, 40, 345–351. [CrossRef]

- Ligthart, K.A.M.; Buitendijk, L.; Koes, B.W.; van Middelkoop, M. The association between ethnicity, socioeconomic status and compliance to pediatric weight-management interventions—A systematic review. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 11 (Suppl. S1), 1–51. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.D.; Aylward, B.S.; Steele, R.G. Predictors of attendance in a practical clinical trial of two pediatric weight management interventions. Obesity 2012, 20, 2250–2256.

- Hagman, E.; Johansson, L.; Kollin, C.; Marcus, E.; Drangel, A.; Marcus, L.; Marcus, C.; Danielsson, P. Effect of an interactive mobile health support system and daily weight measurements for pediatric obesity treatment, a 1-year pragmatical clinical trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2022 Aug;46(8):1527-1533. [CrossRef]

- Metzendorf, M.I.; Wieland, L.S.; Richter, B. Mobile health (m-health) smartphone interventions for adolescents and adults with overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;2(2):CD013591. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Park, M.J.; Seo, Y.G. Effectiveness of Information and Communication Technology on Obesity in Childhood and Adolescence: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(11):e29003. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, L.B.; Stephenson, J.; Ells, L. et al. The effectiveness of e-health interventions for the treatment of overweight or obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2022; 23(2):e13373. [CrossRef]

- DeSilva, S.; Vaidya, S.S. The Application of Telemedicine to Pediatric Obesity: Lessons from the Past Decade. Telemed J E Health. 2021; 27(2):159-166. [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, M.; Alnajjar, F.; Cappuccio, M.; Khalid, S.; Alhmiedat, T.; Mubin, O. Efficacy of Emerging Technologies to Manage Childhood Obesity. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2022; 15:1227-1244. Erratum in: Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2023; 16:2537-2538. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S436332. [CrossRef]

- Quelly, S.B.; Norris, A.E.; DiPietro, J.L. Impact of mobile apps to combat obesity in children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2016; 21(1):5-17. [CrossRef]

- WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006; 450:76-85. [CrossRef]

- De Onis, M.; Onyango, A.W.; Borghi, E.; Siyam, A.; Nishida, C.; Siekmann, J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007; 85(9):660-7. [CrossRef]

- Umano, G.R.; Grandone, A.; Di Sessa, A.; Cozzolino, D.; Pedullà, M.; Marzuillo, P.; Del Giudice, E.M. Pediatric obesity-related non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: waist-to-height ratio best anthropometrical predictor. Pediatr Res. 2021; 90(1):166-170. [CrossRef]

- Cole, T.J. The LMS method for constructing normalized growth standards. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1990; 44(1):45-60.

- Wilding, J.P.H.; Batterham, R.L.; Calanna, S.; Davies, M.; Van Gaal, L.F.; Lingvay, I.; McGowan, B.M.; Rosenstock, J.; Tran, M.T.D.; Wadden, T.A.; Wharton, S.; Yokote, K.; Zeuthen, N.; Kushner, R.F.; STEP 1 Study Group. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2021 18;384(11):989-1002. [CrossRef]

- Ryder, J.R.; Kelly, A.S.; Freedman, D.S. Metrics matter: Toward consensus reporting of BMI and weight-related outcomes in pediatric obesity clinical trials. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2022; 30(3):571-572. [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, T.; Lass, N.; Toschke, C.; Rothermel, J.; Lanzinger, S.; Holl, R.W. Which Amount of BMI-SDS Reduction Is Necessary to Improve Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Overweight Children? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016; 101(8):3171-9. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Going, S.B.; Houtkooper, L.B.; Cussler, E.C.; Metcalfe, L.L.; Blew, R.M.; Sardinha, L.B.; Lohman, T.G. Pretreatment predictors of attrition and successful weight management in women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(9):1124-33. [CrossRef]

- Jelalian, E.; Hart, C.N.; Mehlenbeck, R.S.; Lloyd-Richardson, E.E.; Kaplan, J.D.; Flynn-O’Brien, K.T.; Wing, R.R. Predictors of attrition and weight loss in an adolescent weight control program. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008; 16(6):1318-23. [CrossRef]

- Luppino, G.; Wasniewska, M.; Casto, C.; Ferraloro, C.; Li Pomi, A.; Pepe, G.; Morabito, L.A.; Alibrandi, A.; Corica, D.; Aversa T. Treating Children and Adolescents with Obesity: Predictors of Early Dropout in Pediatric Weight-Management Programs. Children (Basel). 2024; 11(2):205. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.D.; Aylward, B.S.; Steele, R.G. Predictors of attendance in a practical clinical trial of two pediatric weight management interventions. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012; 20(11):2250-6. [CrossRef]

- Rojo, M.; Lacruz, T.; Solano, S.; Gutiérrez, A.; Beltrán-Garrayo, L.; Veiga, O.L.; Graell, M.; Sepúlveda, A.R. Family-reported barriers and predictors of short-term attendance in a multidisciplinary intervention for managing childhood obesity: A psycho-family-system based randomised controlled trial (ENTREN-F). Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2022;30(6):746-759. [CrossRef]

- Skelton, J.A.; Beech, B.M. Attrition in paediatric weight management: a review of the literature and new directions. Obes Rev. 2011; 12(5):e273-81. [CrossRef]

- Roth, L.; Ordnung, M.; Forkmann, K.; Mehl, N.; Horstmann, A. A randomized-controlled trial to evaluate the app-based multimodal weight loss program zanadio for patients with obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2023; 31(5):1300-1310. [CrossRef]

- Desmet, M.; Fillon, A.; Thivel, D.; Tanghe, A.; Braet, C. Attrition rate and predictors of a monitoring mHealth application in adolescents with obesity. Pediatr Obes. 2023; 18(11):e13071. [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, T.; Andler, W. Changes in the atherogenic risk factor profile according to degree of weight loss. Arch Dis Child. 2004; 89(5):419-22. [CrossRef]

- Szczyrska, J.; Brzeziński, M.; Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz, A. Long-term effects of 12-month integrated weight-loss programme for children with excess body weight- who benefits most? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023; 14:1221343. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | data |

|---|---|

| Subjects (n) | 75 |

| Male (%) | 48 |

| Age (IQR) [years] | 9.4 ± 1.5 |

| BMI (IQR) [kg/m2] | 27.6 ± 4.1 |

| Z-score BMI | 3.1 ± 0.7 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure [mmHg] | 113 ± 15 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure [mmHg] | 69 ± 9 |

| Waist Circumference [cm] | 85 ± 10 |

| Waist-to-Height ratio | 0.59 ± 0.06 |

| Standard Care+M-App | Standard Care | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects (n) | 25 | 50 | |

| Male (%) | 44 | 50 | 0.81 |

| Age (IQR) [years] | 10.6 (8.3-10.9) | 9.3 (8-10.3) | 0.20 |

| BMI (IQR) [kg/m2] | 28.1 (25.2-29.5) | 26.8 (24.3-29.9) | 0.99 |

| Z-score BMI (IQR) | 2.9 (2.8-3.3) | 3.3 (2.55-3.65) | 0.32 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (IQR) [mmHg] | 111 (105-118) | 111 (100-125) | 0.45 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (IQR) [mmHg] | 67 (59-75) | 70 (65-80) | 0.14 |

| Waist Circumference (IQR) [cm] | 86 (79-90) | 84 (78-91) | 0.97 |

| Waist-to-Height ratio (IQR) | 0.58 (0.56-0.6) | 0.61 (0.55-0.65) | 0.14 |

| Dropped-out | Returned at follow-up | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects (n) | 46 | 29 | |

| Male (%) | 58 | 41 | 0.48 |

| Age (IQR) [years] | 9.6 (8.4-10.7) | 9.1 (8.1-10.6) | 0.35 |

| BMI (IQR) [kg/m2] | 26.9 (24.8-31.1) | 28.3 (24.0-29.7) | 0.40 |

| Z-score BMI (IQR) | 3.0 (2.4-3.5) | 3.2 (2.9-3.7) | 0.27 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (IQR) [mmHg] | 113 (104-125) | 111 (100-125) | 0.72 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (IQR) [mmHg] | 71 (60-75) | 70 (60-80) | 0.85 |

| Waist Circumference (IQR) [cm] | 84 (79-89) | 89 (77-94) | 0.27 |

| Waist-to-Height ratio (IQR) | 0.60 (0.57-0.63) | 0.59 (0.54-0.65) | 0.47 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).