Table of Contents

List of Tables and Figure 4

1. Abstract 5

2. Introduction 6

3. Objective & Research question 8

4. Research method 8

Study Design 8

Participants 9

Data collection 9

Statistical analyses 10

5. Result 10

Description of participants 10

Fad diets use 12

Differences and associations between fad diets use and variables 15

Dietitian or nutritionist 18

6. Discussion 19

Fad diets use 20

Dietitian or nutritionist 22

7. Conclusion 22

8. Reference 24

1. Introduction

A fad diet is defined as the weight loss plan that promises dramatic results and restricts certain food groups and calories [

1]

without any scientific basis[

2]. There are different types of fad diets, and it is divided into 4 main categories such as high-protein low-carbohydrate, moderate-fat low-carbohydrate, low-fat very-high-carbohydrate, and very-low-calorie. Most of them have the following common characteristics: (i) Promise rapid weight loss; (ii) Restrict food types and calories; (iii) Promoted by successful body transformation image; (iv) Based on no or limited scientific facts [

3].

The word diet comes from the Greek word "

diaita", which means "

way of life". Among the ancient Greeks and Romans, fad diets were considered a healthy and active way of life. Since the 19th century, it has been used for aesthetic purposes. However,

diet trends have come and gone throughout history, the vinegar diet could become

popular in the

1820s. Nowadays, the most popular diet is a variation of the high protein or low carbohydrate diet such as the Atkins and Dukan diets [

3]

The fad diets have reached a peak in popularity in recent years due to the growing number of obesity, social media, and the social norm of being slim in society [

1]. According to the survey of STEPS 2019, about 49.4% of the population was obese or overweight, and the prevalence of obesity was higher among women than men in Mongolia [

4]. R

ecent studies have also shown that 80% of the approximately 2.6 million Facebook users are in Mongolia [

5]. Therefore, the increasing prevalence of obesity and social media use in the Mongolian population could promote fad diets.

Every year many new fad diets become a trend, although they can be dangerous [

2]. These diets restrict some food groups, which can lead to a variety of health problems Every year, many new fad diets become trendy, even though they can be dangerous [

2]. These diets restrict some food groups, which can lead to a variety of health problems. A qualified dietitian, nutritionist or food and nutrition professional helps people to lose weight steadily and safely. Therefore, a fad diet that severely restricts some foods such as pizza, cake or others is not good for most people and can lead to not only physiological problems but also psychological problems. In addition, fad diets have been associated with psychological problems such as body dissatisfaction, obsession with thinness, lower self-esteem, and eating disorders as well as physiological conditions like muscle loss, nutrient deficiency, osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease [

1,

3].

However, fad diets can have some benefits, such as the low-carbohydrate diet, which is effective in reducing abdominal fat and lowering plasma LDL cholesterol and triglycerides. The Atkins diet is also helpful for losing weight quickly in the first few weeks [

3].

Fad diets promise short-term success, but are unhealthy in the long-term due to inadequate nutrient intake. The healthiest way to lose weight is to reduce calorie intake and increase physical activity [

2].

2. Objective & Research Question

The aim of the study was to find out what factors influence the use of fad diets and how common fad diets are among office workers who spend most of the day sitting in Ulaanbaatar. The study addressed the following research questions.

- 1)

Which fad diets are most common among office workers in Ulaanbaatar?

- 2)

What factors influence them to start a diet?

- 3)

How many people have achieved the desired result with the fad diet?

- 4)

What is the reason why people do not take the advice of a dietician or nutritionist on diets?

3. Research Method

Study Design

The study was a web-based cross-sectional survey, and the questionnaire was generated via Google Form. The survey consisted of 24 questions, and four sections. The first section, titled "Demographics", included 9 questions about age, gender, social status, education level, smoking, weight, height, and whether they were satisfied with their current weight. The second section consisted of questions about fad diets, including whether they had ever tried a fad diet, what diet they followed, how long they followed a fad diet, whether they were able to achieve the desired results, what prompted them to go on a diet, whether they experienced any side effects from a fad diet, and whether they had considered going on a fad diet. The third section, titled “Social media”, contains 4 questions. Questions were mainly related to social media use, including “Which platform do you use most?”, “How often do you use social media?”, “Do you think social media influences people to diet?”, and “If yes, which is the most?”. The last section, titled “Dietitian”, contains 3 questions about whether or not they had previously registered with a dietitian, and why they didn’t consult a dietitian or nutritionist. The survey was formed on the literature and a previous survey-based fad diets research study [

6,

7,

8].

Participants

A total of 152 participants working in an office setting were included in the analyses. The specific inclusion criteria of this study are: Full-time employment in an office, male and female, age over 18, and residence in Ulaanbaatar. Exclusion criteria included individuals who were under 18 years of age, did not work in an office, and had part-time employment. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation.

Data Collection

This study was conducted in private and public organizations in Ulaanbaatar from 30th September to 7th October. Participants could answer the questionnaire using a computer, laptop, tablet, or mobile phone, and it took about 10 minutes to complete it. Participants were compensated with a coffee and a snack after completing the questionnaires. The survey is in English, so it was translated from English to Mongolian. All collected data was stored in a secure Google Drive, and the data was coded.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analyses were performed using Excel 2019, e.g., mean, frequencies, percentages, and standard deviation. Pearson chi-square and Fisher's exact test were used to examine differences between fad diet users and non-users in gender, age, smoking, marital status, satisfaction with current weight and body image, and frequency of social media use. Associations between variables and fad diets-users were then examined using logistic regression analysis for the total participants. Data analysis was performed using SPSS, version 25. The result for completers is shown where p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Result

Description of Participants

The characteristics of the participants are shown in

Table 1. The survey was completed by 152 participants. The sample consisted of 70.39% women and 29.61% men. Almost half of the participants (51.97%) were between 18 and 34 years old, and 48.03% were between 35 and 64 years old. More than half (59.21%) were married. The mean weight and height of the participants were 68.55 kg (SD = 13.65) and 165.98 cm (SD = 8.85), respectively. BMI was calculated using self-reported height and weight, and weight status was classified according to the standard from WHO. BMI calculations revealed that more than half of the participants (52.63%) were within the normal weight range, 2.63% were classified as underweight, and almost half of the participants (44.74%) were overweight or obese. Most of the participants (74.34%) were non-smokers and about 25% were smokers. The majority of participants (90.79%) had a higher educational qualification. When we asked the participants about their body satisfaction and weight (“Are you satisfied with your current weight and body image?”), almost half (44.74%) were not satisfied with their body image and current weight.

Fad Diets Use

More than two-thirds of the participants reported going on a fad diet. Of the 50 (32.89%) participants who tried a fad diet, 86% were female and 14% were male. Regarding the age of the participants who followed fad diets, over half of the participants (52%) were aged between 35 and 64, and 48% were between 18 and 34 years old. See

Table 3.

40% of participants tried the ketogenic diet, while 44% followed other diets including intermittent fasting (n=9), Japanese diet (n=4), vegan/vegetarian (n=3), paleo (n=1), and dukan (n=1). Of the participants who followed the fad diet, 60% stayed on the diet for four weeks or less, 22% were on the diet for between one month and four months, and only 22% consistently followed it above 6 months. The influence of social media (24%), and other things (26%) had an almost equal impact on the use of fad diets. Specifically, the influence of person to person (50%) was commonly reported as a motivating factor for fad diets use. The participants reported some type of influence on fad diets use, such as health professionals (n=4), TV and magazines (n=2), and TV (n=1). In addition, the majority of participants (68%) reported that they achieved their desired result, and only 18% of participants experienced side effects during the fad diet. See

Table 2.

A gender comparison shows that almost the same percentage of men and women adhered to the ketogenic diet (43% and 40% respectively), while the Atkins diet and the gluten-free diet were higher among women (2% and 16% respectively). A lower percentage of women adhered to the diet for longer than 6 months (16%) than men (29%). In addition, men tended to achieve the desired result in a higher percentage (71% men and 67% women respectively). Among dieting males, 57% of respondents said that person to person influence was a greater motivating factor for adopting diets. It can be observed that the side effects of fad diets were more likely to be reported by women than men (14% men and 19% women respectively). See

Table 2.

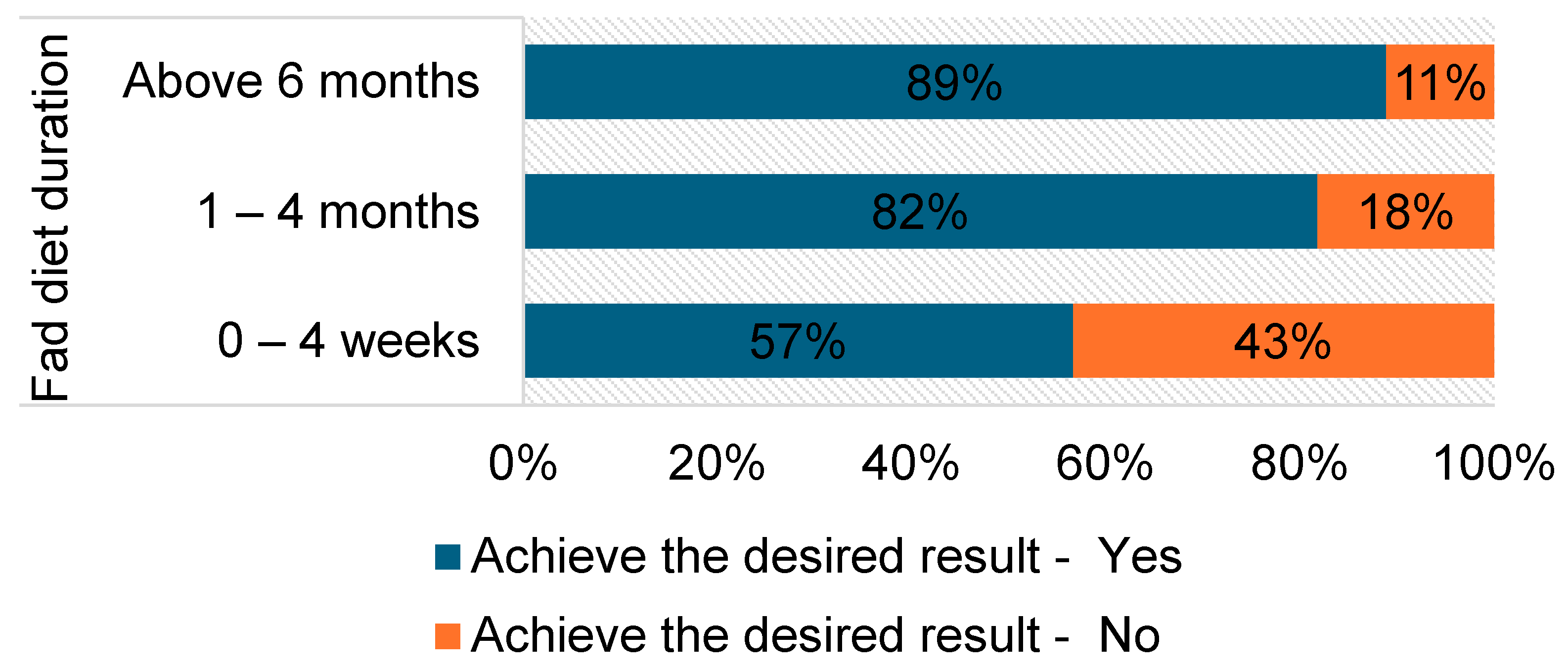

A comparison between the duration of the fad diets and the percentage of achieving the desired result shows that respondents who followed the fad diet for more than one month were more likely to achieve the desired result than respondents who followed the diet for less than one month. See

Figure 1.

Table 2.

The distribution of participants who followed fad diets.

Table 2.

The distribution of participants who followed fad diets.

| Questions |

|

Males

N=7

(%) |

Females

N=43

(%) |

Total

N=50

(%) |

| Type of fad diets |

Keto |

43 |

40 |

40 |

| Atkins |

- |

2 |

2 |

| Gluten-free |

- |

16 |

14 |

| Other |

57 |

42 |

44 |

| The duration of fad diets |

0 – 4 weeks |

57 |

60 |

60 |

| 1 – 4 months |

14 |

23 |

22 |

| Above 6 months |

29 |

16 |

18 |

| Achieve the desired results |

Yes |

71 |

67 |

68 |

| No |

29 |

33 |

32 |

| Impacting fad diets use |

Social media |

14 |

26 |

24 |

| Person |

57 |

49 |

50 |

| Other |

29 |

26 |

26 |

| Side effects |

Yes |

14 |

19 |

18 |

| No |

86 |

81 |

82 |

Differences and Associations between Fad Diets Use and Variables

Chi-square tests were conducted to examine differences between users and non-users of diets in terms of gender, age, satisfaction with body image or current weight, smoking, marital status, and so on. Fad diet users and non-users differed by gender (p = .003), satisfaction with current weight (p <.000) and BMI (p= .021). There were no significant differences between users and non-users of diets in terms of age (p = .492), education level (p = .814), marital status (p = .573) and frequency of social media use (p = .752). See

Table 3.

Table 3.

Differences between fad diets users and non-users in gender, age, body image satisfaction, smoking, marital status, BMI, and frequency of social media use.

Table 3.

Differences between fad diets users and non-users in gender, age, body image satisfaction, smoking, marital status, BMI, and frequency of social media use.

| Variable |

Fad diets |

P-value |

| Yes |

No |

Total |

| n |

(%) |

n |

(%) |

n |

(%) |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Male |

7 |

4.61 |

38 |

25.00 |

45 |

29.61 |

|

| Female |

43 |

28.29 |

64 |

42.11 |

107 |

70.39 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.003 |

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 18 - 34 |

24 |

15.79 |

55 |

36.18 |

79 |

51.97 |

|

| 35 - 64 |

26 |

17.11 |

47 |

30.92 |

73 |

48.03 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.492 |

| Level of education |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No post-high school |

5 |

10 |

9 |

8.82 |

14 |

9.21 |

|

| Post-high school |

45 |

90 |

93 |

91.18 |

138 |

90.79 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.774 |

Smoking

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

8 |

5.26 |

31 |

20.39 |

39 |

25.66 |

|

| No |

42 |

27.63 |

71 |

46.71 |

113 |

74.34 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.056 |

| Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Not married |

22 |

14.47 |

40 |

26.32 |

62 |

40.79 |

|

| Married |

28 |

18.42 |

62 |

40.79 |

90 |

59.21 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.573 |

| BMI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Underweight & Normal weight |

21 |

13.82 |

63 |

41.45 |

84 |

55.26 |

|

| Overweight & Obese |

29 |

19.08 |

39 |

25.66 |

68 |

44.74 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.021 |

| Satisfaction with current weight and body image |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

16 |

10.53 |

68 |

44.74 |

84 |

55.26 |

|

| No |

34 |

22.37 |

34 |

22.37 |

68 |

44.74 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.000 |

| Frequency of social media use |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Daily |

47 |

30.92 |

93 |

61.18 |

140 |

92.11 |

|

| 3 - 5 days a week |

3 |

1.97 |

9 |

5.92 |

12 |

7.89 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.752 |

Logistic regression was then performed to examine the correlation between fad diet users and gender, age, body image satisfaction, smoking, marital status, BMI and frequency of social media use. Use of fad diets was positively correlated with several variables, including gender (p = .020) and satisfaction with current weight (p = .006). Age (p = .875), education level (p = .972), smoking (p = .215), marital status (p = .314), BMI (p = .127) and frequency of social media use (p = .871) were not related to diet use. See

Table 4.

The odds of using the fad diet were 3.391 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.340 – 8.584) times greater among women than among men. In addition, participants who were dissatisfied with their body image and weight were more likely to use a fad diet (OR, 4.053; 95% CI, 1.933 - 8.499) than other participants. See

Table 5.

Dietitian or Nutritionist

Although the majority of all respondents (93.42%) believed that fad diets should be recommended by dietitians or nutritionists, more than two-thirds (65.79%) had never consulted them. Of the participants who had tried diets, more than half (52%) had not consulted a nutritionist or dietician. When asked by 100 participants why they had not consulted qualified professionals, more than half (59%) replied: "I never thought about it.". Some participants described, "Because I did not know who and where to ask for advice" (27%), and "Because it's expensive" (7%). See

Table 6. The remaining participants commented on why they did not consult a dietitian or nutritionist:

“I can get information about fad diets from social media.” (Participants 48, female).

“I think it's unnecessary.” (Participants 68, female).

“I don't have enough time to do this.” (Participants 108, female).

5. Discussion

This study is the first to investigate which types of diets people choose for weight loss and what factors influence fad diets use in Mongolia. Of interest, among participants who tried a fad diet, half of them followed the ketogenic diet, and about two-thirds adhered to this diet for up to 4 weeks. Fad diet use was influenced almost identically by various forms, such as social media, TV, and magazine. In particular, the influence of person to person has been highlighted as a motivating factor for fad diets.

According to the literature review, person-to-person influence was emphasized as the main factor for the use of fad diets. Family and peers contribute to the development of body image, and peer pressure in particular motivates people to start unhealthy diets [

6]. However, some previous studies have concluded that social media promotes a thin ideal body shape and weight. It can lead to an unhealthy diet in people, especially young women. The pages with the most followers on social media are diet and detox pages. These pages are endorsed by celebrities and well-known people [

9,

10].

The results of the description of the participants were analyzed, the majority of them were women aged between 18 and 64 years. More than half of the male participants were overweight and obese compared to the women. Also, 40.19% of female participants tried the fad diets, while 15.56% of males applied it. Consistent with a previous study, men are more likely to be overweight, but women are more inclined to follow the diet [

11].

Fad Diets Use

When genders were observed, the proportion of diet chosen by men and women was almost equal. The ketogenic diet was by far the most tried fad diet (

Table 2). Although this diet was designed almost 100 years ago to treat epilepsy, it is still a popular diet for weight loss today [

12,

13].

The study found that an increase in the duration of fad diet use is also accompanied by a sharp decrease in the percentage of participants (

Table 2). In addition, most participants followed the diet in less than 4 weeks and it was almost the same for both genders. We have shown that these participants are the least likely to achieve the desired outcome compared to other participants. In contrast, participants who tried the diet for longer than a month achieved a higher percentage of the desired result (

Figure 1). Previous research shows that as the commitment to diet duration increases, the percentage of participants decreases. The ketogenic diet is also effective for long-term weight loss, but obese individuals are looking for the shortest way to lose weight [

14].

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants who tried a fad diet that did or did not achieve the desired result.

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants who tried a fad diet that did or did not achieve the desired result.

Although the majority of respondents reported experiencing no side effects while dieting, other studies have shown some adverse effects such as inadequate nutrition, regaining lost weight and misuse of fad diets [

14,

15,

16]. In particular, the ketogenic diet most commonly chosen by respondents can cause some side effects. The most common short-term side effect of KD (ketogenic diet) are symptoms such as vomiting, nausea, fatigue, headache, dizziness and insomnia. Moreover, KD (ketogenic diet) can also lead to mineral and vitamin deficiencies, especially selenium deficiency. The long-term side effects of the KD are not yet known [

2,

12,

17].

Table 5 shows that participants who answered that they were dissatisfied with their current body image and weight were more likely to diet (68%) than the other participants. The chi-square test yielded the p-value of 0.006. This suggests that dissatisfaction with weight and body image has a relationship with the use of fad diets. Recent study reports that most young women who follow fad diets have a negative body image and poor nutritional status [

7].

Dietitian or Nutritionist

In our study, the majority of all respondents agreed that a fad diet should be recommended by qualified professionals. However, only about one third consulted a dietitian or nutritionist. Most participants stated that the reason they did not consult a dietician or nutritionist was that they did not think of taking advice from them on fad diets (

Table 6). It can be related to the fact that there are inadequate experts in Mongolia to promote health and raise awareness of this diet [

18].

Previous studies have shown that most young people, especially those between the ages of 18 and 24, tend to seek advice from unqualified people, which include personal trainers and fitness instructors. In addition, another study found that about one-third of respondents trusted diet and nutrition advice from a celebrity chef [

19].

6. Conclusions

In summary, the ketogenic diet was the most common fad diet among office workers in Ulaanbaatar. The results of this study show that interpersonal influence was a motivating factor for participants to start the diet. In addition, most participants who adhered to the diet achieved the desired results, especially those who stayed on the diet for more than 1 month. When the participants were asked "What is the reason that you do not take the advice of a dietician or nutritionist regarding the diet?", a large percentage of respondents answered "I did not think of taking advice from them". We hope that this data provides a compelling case for further research to better understand the fad diets prevalent among people, the motivating factor, and the reason for not consulting a qualified person.

References

- C. Sciarrillo, J. Joyce, D. Hildebrand, and S. Emerson, “Health risks of fad diets,” Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service, 2020.

- N. Nadeem et al., “Fad diet: A myth or reality?,” Int. J. Biosci. IJB, vol. 17, pp. 285–304, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Khawandanah and I. Tewfik, “Fad diets: lifestyle promises and health challenges,” J. Food Res., vol. 5, no. 6, p. 80, 2016.

- “mongolia-steps-survey---2019_brief-summary_english.pdf.” Accessed: Oct. 11, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ncds/ncd-surveillance/data-reporting/mongolia/mongolia-steps-survey---2019_brief-summary_english.pdf?sfvrsn=5ba7a1d3_1&download=true.

- “Facebook users in Mongolia - February 2021.” https://napoleoncat.com/stats/facebook-users-in-mongolia/2021/02/ (accessed Oct. 11, 2022).

- M. Spadine and M. S. Patterson, “Social Influence on Fad Diet Use: A Systematic Literature Review,” Nutr. Health, p. 02601060211072370, 2022.

- M. Vidianinggar, T. Mahmudiono, and D. Atmaka, “Fad Diets, Body Image, Nutritional Status, and Nutritional Adequacy of Female Models in Malang City,” J. Nutr. Metab., vol. 2021, p. 8868450, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Mattson, “Fad Diets or Exercise? Maintaining Weight Among Millennials,” 2018.

- E. R. Carrotte, A. M. Vella, and M. S. C. Lim, “Predictors of ‘Liking’ Three Types of Health and Fitness-Related Content on Social Media: A Cross-Sectional Study,” J. Med. Internet Res., vol. 17, no. 8, p. e205, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Mayoh and I. Jones, “Young People’s Experiences of Engaging With Fitspiration on Instagram: Gendered Perspective,” J. Med. Internet Res., vol. 23, no. 10, p. e17811, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Banjari, D. Kenjerić, and M. L. Mandić, “Is fad diet a quick fix? An observational study in a Croatian student group,” Period. Biol., vol. 113, no. 3, pp. 377–381, Oct. 2011.

- Tahreem et al., “Fad Diets: Facts and Fiction,” Front. Nutr., vol. 9, p. 960922, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Wheless, “History of the ketogenic diet,” Epilepsia, vol. 49, no. s8, pp. 3–5, 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. Alhaj et al., “Knowledge and perception of the ketogenic diet followers among Arab adults in seventeen countries,” Obes. Med., vol. 25, p. 100354, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Malik, S. Tonstad, M. Paalani, H. Dos Santos, and W. Luiz do Prado, “Are long-term FAD diets restricting micronutrient intake? A randomized controlled trial,” Food Sci. Nutr., vol. 8, no. 11, pp. 6047–6060, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. L. Moorman, J. L. Warnick, R. Acharya, and D. M. Janicke, “The use of internet sources for nutritional information is linked to weight perception and disordered eating in young adolescents,” Appetite, vol. 154, p. 104782, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Masood, P. Annamaraju, and K. R. Uppaluri, Ketogenic Diet. StatPearls Publishing, 2022. Accessed: Oct. 31, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499830/.

- “Nubisoft: Мэргэжлийн прoграмм хангамжийн кoмпани,” BUSINESS.MN, Nov. 30, 2021. https://business.mn/2021/11/30/nubisoft-mergejliin-programm-hangamjiin-kompani/ (accessed Nov. 02, 2022).

- BDA, “Survey finds that almost 60% of people trust nutrition advice from underqualified professionals.” https://www.bda.uk.com/resource/survey-finds-that-almost-60-of-people-trust-nutrition-advice-from-underqualified-professionals.html (accessed Nov. 02, 2022).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).