Highlights

Depression symptoms among older adults in China were evaluated.

Data from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study Wave 5 (2020) were used.

Chi-squared analysis and a binary logistic regression model were applied.

Older adults whose BADL and IADL were not limited had a lower risk of depression than those whose BADL and IADL were limited.

Internet use was highly important for preventing depression in rural residents.

Disabilities limiting BADL and IADL were more likely to be associated with depressive symptoms in rural Chinese older adults.

Introduction

Depression is a prevalent mental health disorder among the elderly population, and it affects approximately 7% of older adults worldwide [

62]. Depression has emerged as a significant global health concern that carries a substantial disease burden [

30]. Depression contributes to 12.1% of the total years lived with disability and accounts for 4.5% of the global disability-adjusted years (DALYs) [

38]. Despite ongoing uncertainty of its exact pathogenesis, scientific research has explored the relationship between depression in elderly people and social support [

67] [

29], suicidal tendencies [

34] [

54], obesity [

27] and chronic medical conditions [

20]. Considering the ageing population in China, the burden of depression diminishes the quality of life for millions of people and places considerable strain on society via prolonged nursing and medical services [

59]. Because China has the greatest number of elderly individuals globally, it is crucial to pay adequate attention to the challenges posed by depressive symptoms in the elderly population [

13] [

48]. In 2019, the World Health Organization reported that there were approximately 1 billion individuals above 60 years of age, and this number is projected to rise to 2.1 billion by the year 2050 [

49]. Ageing is linked to declines in physical health [

12], cognitive health [

66] and an elevated risk of psychiatric issues, including depression.

Similarly, the occurrence of disability that limits an individual’s ADL is prevalent among older people [

1] [

18]. Activities of daily living (ADL) are functional limitation indicators in older people and are typically classified into instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and basic activities of daily living (BADL) [

5]. IADL and BADL encompass two aspects of the activity ability of older adults [

64]. BADL pertains to the fundamental self-care abilities that individuals must perform repeatedly daily to live alone, and IADL reflects the more complex ability of an individual to live alone and engage in social activities [

64].

Previous studies indicated that having a disability that limits an individual’s ADL may serve as a risk factor for depressive symptoms [

60]. Having a disability that limits an individual’s ADL is associated with symptoms of depression and an increased psychological burden among older adults [

26]. An article examining depression levels among older Turkish individuals suggested that having a disability that limits an individual’s ADL was predictive of depressive symptoms in older adults [

37]. However, most studies have focused on Malaysia [

2], Japan [

22], and Nigeria [

3], and few studies have investigated the impact of ADLs on depression in older adults in China. In the past few years, studies have investigated the impact of ADLs on the health status of older people who participated in the 2015 and 2018 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) [

60]. Research examining the relationships between BADLs or IADLs and the scores obtained on the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D-10) scale among Chinese elderly people who were part of the 2020 CHARLS is scarce. No research has explored the possible associations between depression risk and IADL or BADL among elderly people at the individual and provincial levels or in rural and urban subgroups. To address these knowledge gaps, the present study analysed the relationships between IADL or BADL and depression among older Chinese people using chi-squared tests and binary logistic regression techniques based on data from the 2020 CHARLS. This study is important because the results will contribute to the development of policies in the field of social work for older individuals in the community and the implementation of policies aimed at promoting care for older adults with IADL or BADL in China.

Methods

Sample and Data Collection

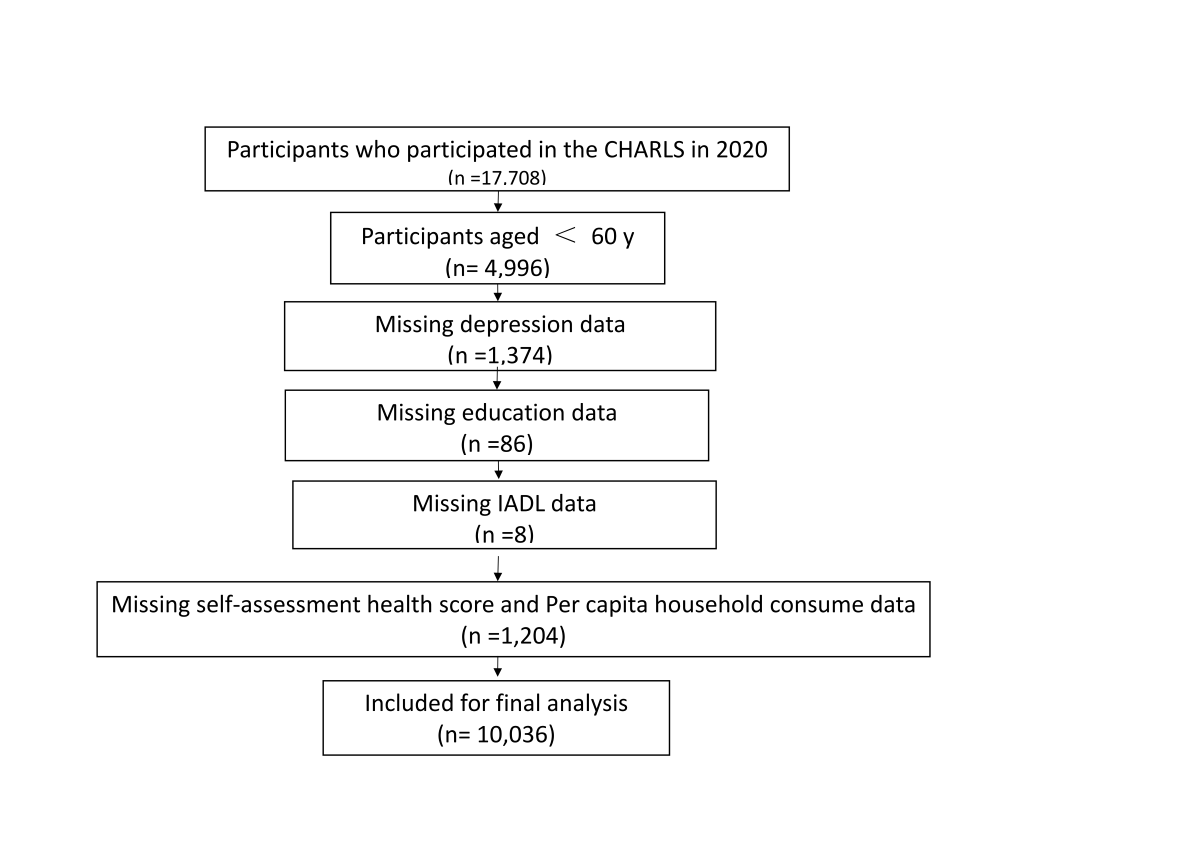

The dataset used in this research was from the 2020 wave (Wave 5) of CHARLS, which was a national representative and comprehensive survey led by the China Centre for Economic Research located at Peking University. This extensive survey gathered detailed information related to the demographic and socioeconomic backgrounds, relevant behaviours, and health of people aged 45 years and older across China. Using a probability-proportional-to-size (PPS) multistage sampling technique [

51] [

24], in conjunction with Kalton's methodology for participant recruitment [

21], the survey covered 28 provinces that encompassed 450 communities or villages throughout 150 counties or districts in 2020. The dataset included information from 17,708 individuals aged 45 years and older residing in 10,257 households. To investigate the association between the risk of depression and use of the internet, the dataset was refined by removing missing data (

Figure S1) and focused specifically on 10,036 respondents meeting the following criteria: (1) available data on CES-D-10 scores and internet use; and (2) over the age of 60 years, which is an accepted threshold for the definition of old people in China.

Ethical Considerations

Before the CHARLS survey was performed, thoroughly trained interviewers briefed participants on the survey's contents, and informed consent forms were signed by the interviewees. The information of the survey is confidential, and all of the respondents’ data are protected by privacy regulations and rigorous data security. Peking University’s Ethics Review Committee provided ethical approval for all CHARLS iterations (ethical approval no. IRB 00001052-11015). This study adhered to the reporting guidelines of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) (refer to

Table S1 for the checklist of STROBE).

Measurement

Dependent Variable

The 2020 CHARLS (China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study) used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-10 (CES-D-10) to assess depression levels among the study participants. The 10-item scale concentrates on capturing the behaviours and feelings of the interviewees during the previous week, as detailed in

Table S2. Scoring and Interpretation: The items of the CES-D-10 are assessed on a 4-point scale, with 0 indicating little or no depression (<1 day), 1 indicating not much depression (1–2 days), 2 indicating depression half of the time or sometimes (3–4 days), and 3 indicating frequent depression (5–7 days). The range of total depression scores is 0 to 30, where lower scores suggest a lower degree of depression, and higher scores indicate a greater degree of depression. The CES-D-10 is a reliable and valid tool for assessing depression among older adults in China [10; 46]. Additionally, past studies used a threshold of 12 for the identification of individuals suffering from depression, which is an effective approach in the detection of clinical depression in this population [

33]. Therefore, a binary variable with 12 as the cut-off point was used to determine depression among the respondents, with a score of 0 indicating no depression and a score of 1 indicating depression. Individuals with a score of 12 or greater were classified as suffering from depression.

Independent Variables

BADL

In the 2020 CHARLS questionnaire, the following questions (DB001, DB003, DB005, DB007, DB009, DB011) were used for the measurement of BADL: “Do you have difficulty dressing, bathing, eating, getting up or getting out of bed, going to the toilet, controlling urine and faeces?”.

IADL

In the 2020 CHARLS questionnaire, the following questions (DB012, DB014, DB016, DB018, DB020, DB022) were used for the measurement of BADL: “Do you have trouble doing housework, cooking, buying groceries in stores, making phone calls, taking medicine, or managing money because of your health and memory?”.

The first option was selected to encode “0” for each item. Any item selection after the three options were encoded as “1”.

Covariates

We examined covariates at the individual and province levels [

45]. At the individual level, various sociodemographic factors were considered, including age, sex, marital status, residence and educational attainment. Health indicators such as self-rated health (SRH) scores and chronic diseases were considered. Additionally, lifestyle variables, including drinking, smoking, and level of physical exercise, were also considered.

To assess social participation, we chose nine overt activities from the 2020 CHARLS questionnaire item DA038, and activities that constituted less than 0.5% of the participant population were excluded. The following were the chosen activities: (1) visiting friends or engaging in social activities with friends; (2) participating in games, such as chess, mahjong, and cards, with indoor activities; (3) lending a helping hand to friends, neighbours, and relatives not living together; (4) joining community activities, such as physical exercise, dancing or Qigong; (5) taking part in gatherings and events in the community; (6) becoming involved in charity events, volunteer activities or caring for the disabled and patients; (7) attending school classes or relevant training programs; (8) taking part in other activities; and (9) participating in none of the above activities. For each of the chosen social participation variables, a 0–7 range score was assigned, where higher scores indicate greater social engagement. Excluding the ninth option, all values were regarded as indicative of social activities. The assessment of physical activity was primarily based on the respondents’ participation in low-intensity, moderate-intensity, or high-intensity physical exercise on a weekly basis. The number of chronic diseases was used as the main metric to evaluate the health conditions of respondents in the long run. Please check the specific guidelines for covariate value assignment in Table 1.

In addition, the covariates at the provincial level encompassed the provincial GDP per capita for the year 2020. The GDP per capita was determined by dividing the nation’s total GDP by the total population, which reflected the nation's standard of living and economic development. This measure is essential for assessing the economic well-being and development of a region or country. It offers insightful information regarding the standard of economic growth, living, and overall economic health of a region or country. For this study, the regions were categorised on the basis of the classifications provided by the "State Statistical Bureau".

Please see Table 2 for detailed information.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS Statistics software of IBM (version 26). The descriptive statistics were first calculated to summarise the primary characteristics of the variables under study. For categorical variables, percentages (%) and frequencies (n) are presented. Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided P value less than 0.05. For continuous variables, standard deviations and means are reported. To examine the fundamental characteristics of the subgroups residing in the eastern, central, and western regions, a univariate analysis test was performed, and the detailed results are presented in

Table S3. Logistic regression was subsequently used to assess the correlation between depression risk and internet use. This analysis provided insights into the connection between internet use and depression risk among the study participants. To delve deeper into the relationship between depression risk and internet use dimensions within urban and rural subgroups, a group regression analysis was specifically performed within these distinct demographic segments.

Results

As presented in Table 3, the sample was comprised 10,036 individuals from 31 provinces, including 4853 (48.4%) males and 5183 (51.6%) females. The average age was 69.2 years. Most of the respondents (4425/10036, 50.9%) had a low educational level, approximately one-tenth (1112/10036, 11.1%) had high school education or higher, and some (4018/10036, 40.0%) had middle school education or lower. Most of the respondents were aged 60-69(n=5,856, 58.3%), had partners (n=7,902 78.7%), lived in rural areas (n=6,090, 60.7%), had retirement pensions (n=7,962, 79.3%), had 3 or more children (n=5,251, 52.3%) and did not participate in social activities (n=5,403, 53.8%). Additionally, a significant number of the respondents did not drink (n=6,700, 66.8%), smoke (n=2,524, 25.1%) or exercise (n=8,844, 88.1%), had fair SRH scores (n=5,044, 50.3%), had no chronic diseases (n=6,013, 59.9%) and had an above average per capita household consumption (n=5779, 57.6%). Most of the sample consisted of individuals whose BADL were not limited (7277/10036, 72.5% vs. 2759/10036, 27.5%) and individuals whose IADL were not limited (7460/10036, 74.3% vs. 2576/10036, 25.7%). Among the participants with depressive symptoms, 2339 (32.1%) were not limited in their BADL, and 1703 (61.7%) were limited in their BADL. Among participants without depressive symptoms, 4938 (67.9%) were not limited in their BADL and 1056 (38.3%) were limited in their BADL. Among the participants with depressive symptoms, 2426 (32.5%) were not limited in their IADL, and 1616 (62.7%) were limited in their IADL. Among participants without depressive symptoms, 5034 (67.5%) were not limited in their IADL, and 960 (37.3%) were limited in their IADL. Most of the participants lived in provinces in the first quartile of GDP per capita (n=2,732, 27.2%) and provinces with the second quartile of the number of beds in medical institutions per 10,000 persons (n=2,713, 27.0%).

We used a chi-squared test to determine significant differences between depression and having limited BADL, having limited IADL, sex, age, education, place of residence, retirement pension, per capita household consumption, number of children, number of chronic diseases, SRH score, smoking status, drinking status, exercise status, social engagement status, GDP per capita and number of beds in medical institutions per 10,000 persons. Table 3 shows that there were no significant differences between depressive symptoms and smoking status (P = .680). Compared with healthy participants, those experiencing depressive symptoms were more likely to not have a disability that limited their BADL (P < .001) and not have a disability that limited their IADL (P < .001), be female (P<.001), be 60-69 years old (P < .005), have a partner (P < .001), be literate (P<.001), live in a rural area (P < .001), have a retirement pension (P < .001), have 3 or more children (P < .001), not have any chronic diseases (P < .001), have a fair SRH score (P <.001), drink alcohol (P < .001), exercise (P < .005), not participate in social activities (P <. 001), have an above average per capita household consumption (P < .001), live in provinces with the first quartile of GDP per capita (P < .001) and live in provinces with the second quartile of the number of beds in medical institutions per 10,000 persons (P < .001).

We also analysed the odds ratio (OR) for older adults with depressive symptoms (vs. non-depressive symptoms) for each predictor using binary logistic regression. Table 4 shows that older adults whose BADL were not limited (OR=1.942, 95% CI=1.638, 2.303) had a lower risk of depressive symptoms than participants whose BADL were limited, and participants whose IADL were not limited (OR=1.775, 95% CI=1.485, 2.122) had a lower risk of depressive symptoms than participants whose IADL were limited. In addition, older adults who were single (OR=0.669, 95% CI=0.551, 0.812), illiterate (OR=0.646, 95% CI=0.504, 0.828), living in rural areas (OR=1.485, 95% CI=1.270, 1.735), did not have retirement pensions (OR=0.671, 95% CI=0.582, 0.819) and had very bad SRH scores (OR=0.411, 95% CI=0.311, 0.544) were more likely to exhibit depressive symptoms.

We also performed monofactor analysis of GDP per capita and the number of beds in medical institutions per 10,000 persons for all four regions. Table 3 shows that there were significant differences in GDP per capita (P < .001), and the number of beds in medical institutions per 10,000 persons (P < .001). Only the eastern region (mean=87752.52) was above the total mean GDP (mean=66933.17), and the central (mean=59787.21), northeastern (mean=52435.20), and western (mean=56316.88) regions were below the total mean. Although the western (n=2866) population was the largest, it had a lower mean (mean=56316.88), which indicated that the GDP per capita in the west was lower. Only the east (mean=57.481) was below the total mean (mean=66.060) of the number of beds in medical institutions per 10,000 persons. The central (mean=68.251), northeast (mean=74.801) and western (mean=70.608) regions were all greater than the total mean. However, the eastern (n=2715) population was the largest but had a lower mean (mean=74.801), which indicated that the number of beds in medical institutions per 10,000 persons in the east was lower.

Table 5 shows that older adults whose BADL were not limited (OR=2.219, 95% CI: 1.636–3.010, P < .001) were less likely to exhibit depressive symptoms than participants whose BADL were limited, and older adults whose IADL were not limited (OR=1.967, 95% CI: 1.435–2.698, P < .001) were less likely to exhibit depressive symptoms than participants whose IADL were limited. In urban areas, older adults who had very poor SRH scores (OR 0.331, 95% CI 0.200–0.546; P < .001) had a greater risk of depressive symptoms than others, and the number of beds in medical institutions per 10,000 persons in Q3 (OR 1.744, 95% CI 1.194–2.547; P < .005) was associated with a greater risk of developing depressive symptoms than other areas. In rural areas, older adults who had very poor SRH scores (OR 0.467, 95% CI 0.334–0.655; P < .001) had a greater risk of developing depressive symptoms than others, and literate participants (OR 0.598, 95% CI 0.427–0.838; P < .005), and those with no old-age pension (OR 0.707, 95% CI 0.577–0.866; P < .005) had a greater risk of developing depressive symptoms than other participants.

Discussion

Using data from the 2020 CHARLS, we compared characteristic differences in older populations with depressive symptoms. Additionally, we used binary logistic regression models to identify urban‒rural disparities in having limited IADL, BADL and depressive symptoms among Chinese adults. This study revealed the following key findings: (1) having limited BADL, IADL, sex, age, marital status, chronic diseases, self-rated health, number of children, old-age pension, drinking, GDP per capita, exercising, social participation, per capita household consumption, and bed number per 10,000 people were associated with symptoms of depression, and (2) older adults in rural areas with disabilities limiting their IADL and BADL had a greater likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms.

We also observed an association between depressive symptoms and having limited IADL in the managing of money and medical care, which underscores the loss of control in key areas other than physical limitations [

35]. In general, compared to other practical skills, budgeting and financial management abilities are typically obtained in later life stages [

23], and a lack of proficiency in these skills may result in disruptions to the daily lives of older individuals [

44]. Effective money management enables seniors to achieve financial independence and a sense of security [

9]. By practising good financial management, older adults can alleviate stress caused by poverty to some extent [

36] and obtain better medical resources [

16] and quality of life [

25].

We also investigated the relationship between the BADL-specific factors and depressive symptoms and revealed that having a disability limits one’s IADL was linked to developing depressive symptoms. Older adults often struggle with performing daily activities at home and require long-term care from their family or other people. This long-term care can create tension between the older adults and caregivers, which directly impacts the setup and maintenance of their social networks. Therefore, depressive symptoms may emerge, and these factors interact and exacerbate each other, which resulted in older adults suffering worsening conditions in a vicious cycle [

28]. Moreover, difficulties in personal care for older adults can result in the formation of negative biases via pessimistic thoughts and judgments, which may increase their risk of experiencing depressive symptoms as they cope with stress during periods of declining health [

15] [

65] [

41].

Our survey revealed that depressive symptoms were more prevalent among rural elderly people than among their urban counterparts. The widening gap between urban and rural areas due to rapid socioeconomic development has led to a situation where young and middle-aged workers migrate to municipalities and leave children and older people behind in rural areas. This migration underscores the need for greater attention to be given to the mental health of older people [

16], particularly those living alone in the countryside, who are at greater risk of experiencing depressive symptoms [

43]. The "empty nester" phenomenon may contribute to the increased prevalence of depressive symptoms among older rural people in China [

19]. Family values are highly important to Chinese adults [

14]. In rural areas, children leaving their homes to work outside their hometowns often leads to separation from their parents and results in reduced contact and increased loneliness for elderly individuals [

8] Additionally, the burden of caring for babies among old rural people has expanded [

7]. Therefore, older Chinese adults in rural areas require additional social support. The social environment significantly impacts the health of older adults [

52], with urban older adults having better financial assistance and medical resources compared to older adults in rural areas[

29]. Older urban adults have the opportunity to engage in social activities and gain spiritual comfort during their leisure time [

57]. These observations highlight the need for the government and society to prioritise the psychological well-being of older rural adults by effectively allocating resources, expanding public service provision, and bridging the gap between rural and urban areas [

53].

These findings indicated that various factors, including marital status, residence, drinking habits, having a disability that limits ADL, physical function, and self-rated health, were associated with depressive symptoms. Notably, our study revealed that older people who were married presented lower rates of depression. Research on the elderly population has also emphasised the significant role of marital status as a predictor of depression, with single older adults being more prone to depression [

32]. Specifically, single or separated older adults reported higher levels of depression [

32]. Older adults experience psychological effects from various events, and self-rated health strongly correlated with depressive symptoms in a survey of community-dwelling older adults [

47]. There is growing evidence suggesting that older adults who perceive their health as poor tend to have higher levels of depression [

61] [

31]. Our findings are consistent with prior studies showing that high education levels increase human capacity and personal capital [

11] and reduce risky behaviours [

11] and unhealthy lifestyles [

55], such as physical inactivity [

55] and drug abuse [

42].

Finally, the present study focused on examining the relationship between IADL, BADL and depression among older adults in rural and urban areas of China. Limitations in physical function and daily activities can result in a loss of independence for older adults, which ultimately results in depressive symptoms and sorrow. These conditions may also contribute to financial and psychosocial difficulties. There is considerable evidence indicating that older people with greater functional limitations are prone to experiencing depressive symptoms [

42]. Specifically, disabilities in IADL and BADL may facilitate the development of depressive symptoms [

39]. The present study contributes to existing research by examining the associations among IADL, BADL, and depression. The findings indicated that depressed older adults were prone to having disabilities in IADL and BADL. Other studies also reported a strong correlation between disabilities that limits an individual’s ability to perform IADL and BADL and depression risk among older adults in rural areas [

58]. Our study further confirms this relationship.

The relationship between depressive symptoms and IADL/BADL in older people is intricate and may indicate a reciprocal and potentially escalating connection [

50]. It is challenging to articulate their precise mechanism unequivocally. Typically, older people initially encounter limitations in IADL, followed by BADL. The constraints in IADL are accompanied by an increase in negative emotions and a decrease in goal-oriented behaviour. BADL limitations correlate with a decline in physical function, such as reduced lower body strength or compromised mobility, which impacts the mood of individuals [

58]. Moreover, these limitations can hinder activities and diminish social engagement, which ultimately contribute to depression [

63] [

56]. The deterioration of BADL is also linked to a decline in physical function, including impaired mobility or the loss of lower body strength, which can affect the mood of individuals [

40]. Therefore, it is imperative for the Chinese government and society to prioritise the physical health of older adults, particularly those residing in the countryside. They should provide additional support to older adults experiencing IADL and BADL disabilities. Moreover, a sedentary lifestyle has been identified as a contributing factor to the decline in the ability of older adults to perform IADL and BADL tasks [

17]. Regular physical activity is crucial for enhancing functional capacity [

4] and promoting mental health [

6].

Limitations

There are several limitations to the current study that must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes the ability to draw causal inferences. Second, the CES-D-10 may be subject to recall bias and is only suitable for screening for depressive symptoms not diagnosing depression. Third, the old people in this study were selected from a database of 23,000 respondents and may not be representative of the original data. Finally, the use of self-reported data may lead to an overestimation of the associations between depressive symptoms and the variables.

Conclusion

The present study provides evidence of an association between having a disability that limits one’s ability to perform BADL, IADL and having depression in older Chinese adults. The results revealed that being limited in BADL (P < .001), being limited in IADL (P < .001), being female (P < .001), being 60-69 years of age (P < .005), having a partner (P < .001), being literate (P < .001), living in a rural area (P < .001), having retirement pension (P < .001), having 3 or more children (P < .001), not having any chronic diseases (P < .001), having a fair SRH score (P < .001), drinking alcohol (P < .001), exercising (P < .005), not participating in social activities (P < .001), having an above average per capita household consumption (P < .001), living in the provinces with the first quartile of GDP per capita (P < .001) and living in provinces with the second quartile of the number of beds in medical institutions per 10,000 persons (P < .001) constituted a greater proportion of depressed older adults. Binary logistic regression models based on rural older adults in China indicated that individuals with a disability that limits their IADL and BADL were prone to developing depressive symptoms. To prevent physical dysfunction, it is recommended that older adults engage in moderate social and physical activities. Furthermore, social and government organisations should prioritise the mental health of older adults in rural areas.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Zuo Xinyi: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, and Writing – review & editing.

Funding

There was no funding received for this study.

Statement of Data Availability

The original data have been included in the supplementary materials, and further inquiries may be made directly to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

Zuo Xinyi confirmed the submission of this manuscript, the key message of the manuscript and the uniqueness of the study. I express my gratitude to the reviewers for their valuable remarks.

Declarations

Patient Ethics and Consent to Participate declarations: Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest Statement

I declare that I have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organisations that can inappropriately influence our work. There is no professional or other personal interest of any nature in any product, service or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, this manuscript.

References

- Agüero-Torres, H., Hillerås, P. K., & Winblad, B. (2001). Disability in activities of daily living among the elderly. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 14(4), 355-359. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N. A., Abd Razak, M. A., Kassim, M. S., Sahril, N., Ahmad, F. H., Harith, A. A., Mahmud, N. A., Abdul Aziz, F. A., Hasim, M. H., & Ismail, H. (2020). Association between functional limitations and depression among community-dwelling older adults in Malaysia. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 20, 21-25. [CrossRef]

- Akosile, C. O., Mgbeojedo, U. G., Maruf, F. A., Okoye, E. C., Umeonwuka, I. C., & Ogunniyi, A. (2018). Depression, functional disability and quality of life among Nigerian older adults: Prevalences and relationships. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 74, 39-43. [CrossRef]

- Angulo, J., El Assar, M., Álvarez-Bustos, A., & Rodríguez-Mañas, L. (2020). Physical activity and exercise: Strategies to manage frailty. Redox biology, 35, 101513. [CrossRef]

- Beltz, S., Gloystein, S., Litschko, T., Laag, S., & van den Berg, N. (2022). Multivariate analysis of independent determinants of ADL/IADL and quality of life in the elderly. BMC geriatrics, 22(1), 894. [CrossRef]

- Callow, D. D., Arnold-Nedimala, N. A., Jordan, L. S., Pena, G. S., Won, J., Woodard, J. L., & Smith, J. C. (2020). The mental health benefits of physical activity in older adults survive the COVID-19 pandemic. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry, 28(10), 1046-1057. [CrossRef]

- Carr, D., & Utz, R. L. (2020). Families in later life: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 346-363. [CrossRef]

- Carr, S., & Fang, C. (2023). A gradual separation from the world: a qualitative exploration of existential loneliness in old age. Ageing & Society, 43(6), 1436-1456. [CrossRef]

- Cassum, L. A., Cash, K., Qidwai, W., & Vertejee, S. (2020). Exploring the experiences of the older adults who are brought to live in shelter homes in Karachi, Pakistan: a qualitative study. BMC geriatrics, 20, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., & Mui, A. C. (2014). Factorial validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale short form in older population in China. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(1), 49-57. [CrossRef]

- Deming, D. J. (2022). Four facts about human capital. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 36(3), 75-102. [CrossRef]

- Eckstrom, E., Neukam, S., Kalin, L., & Wright, J. (2020). Physical activity and healthy aging. Clinics in geriatric medicine, 36(4), 671-683. [CrossRef]

- Fang, E. F., Xie, C., Schenkel, J. A., Wu, C., Long, Q., Cui, H., Aman, Y., Frank, J., Liao, J., & Zou, H. (2020). A research agenda for ageing in China in the 21st century: focusing on basic and translational research, long-term care, policy and social networks. Ageing research reviews, 64, 101174. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z., Glinskaya, E., Chen, H., Gong, S., Qiu, Y., Xu, J., & Yip, W. (2020). Long-term care system for older adults in China: policy landscape, challenges, and future prospects. The Lancet, 396(10259), 1362-1372. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z., Li, Q., Zhou, L., Chen, Z., & Yin, W. (2021). The relationship between depressive symptoms and activity of daily living disability among the elderly: results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Public Health, 198, 75-81. [CrossRef]

- Fulmer, T., Reuben, D. B., Auerbach, J., Fick, D. M., Galambos, C., & Johnson, K. S. (2021). Actualizing Better Health And Health Care For Older Adults: Commentary describes six vital directions to improve the care and quality of life for all older Americans. Health Affairs, 40(2), 219-225. [CrossRef]

- Garcia Meneguci, C. A., Meneguci, J., Sasaki, J. E., Tribess, S., & Júnior, J. S. V. (2021). Physical activity, sedentary behavior and functionality in older adults: A cross-sectional path analysis. PloS one, 16(1), e0246275. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Wang, T., Ge, T., & Jiang, Q. (2022). Prevalence of self-care disability among older adults in China. BMC geriatrics, 22(1), 775. [CrossRef]

- Huang, G., Duan, Y., Guo, F., & Chen, G. (2020). Prevalence and related influencing factors of depression symptoms among empty-nest older adults in China. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 91, 104183. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.-h., Zhu, F., & Qin, T.-t. (2020). Relationships between chronic diseases and depression among middle-aged and elderly people in China: a prospective study from CHARLS. Current Medical Science, 40(5), 858-870. [CrossRef]

- Kalton, G. (2020). Introduction to survey sampling. Sage Publications.

- Kim, B. J., Liu, L., Nakaoka, S., Jang, S., & Browne, C. (2018). Depression among older Japanese Americans: The impact of functional (ADL & IADL) and cognitive status. Social work in health care, 57(2), 109-125. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P., Pillai, R., Kumar, N., & Tabash, M. I. (2023). The interplay of skills, digital financial literacy, capability, and autonomy in financial decision making and well-being. Borsa Istanbul Review, 23(1), 169-183. [CrossRef]

- Latpate, R., Kshirsagar, J., Kumar Gupta, V., Chandra, G., Latpate, R., Kshirsagar, J., Kumar Gupta, V., & Chandra, G. (2021). Probability proportional to size sampling. Advanced sampling methods, 85-98.

- Lee, K. H., Xu, H., & Wu, B. (2020). Gender differences in quality of life among community-dwelling older adults in low-and middle-income countries: results from the Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). BMC Public Health, 20, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Li, A., Wang, D., Lin, S., Chu, M., Huang, S., Lee, C.-Y., & Chiang, Y.-C. (2021). Depression and life satisfaction among middle-aged and older adults: mediation effect of functional disability. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 755220. [CrossRef]

- Liao, W., Luo, Z., Hou, Y., Cui, N., Liu, X., Huo, W., Wang, F., & Wang, C. (2020). Age and gender specific association between obesity and depressive symptoms: a large-scale cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 20, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Lilleheie, I., Debesay, J., Bye, A., & Bergland, A. (2021). The tension between carrying a burden and feeling like a burden: a qualitative study of informal caregivers’ and care recipients’ experiences after patient discharge from hospital. International journal of qualitative studies on health and well-being, 16(1), 1855751. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Xi, J., Hall, B. J., Fu, M., Zhang, B., Guo, J., & Feng, X. (2020). Attitudes toward aging, social support and depression among older adults: Difference by urban and rural areas in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 85-92. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., He, H., Yang, J., Feng, X., Zhao, F., & Lyu, J. (2020). Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. Journal of psychiatric research, 126, 134-140. [CrossRef]

- Lu, N., Wu, B., Pei, Y., & Peng, C. (2022). Social capital, perceived neighborhood environment, and depressive symptoms among older adults in rural China: the role of self-rated health. International Psychogeriatrics, 34(8), 691-701. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Xiang, Q., Yan, C., Liao, H., & Wang, J. (2021). Relationship between chronic diseases and depression: the mediating effect of pain. BMC psychiatry, 21, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Maj, M., Stein, D. J., Parker, G., Zimmerman, M., Fava, G. A., De Hert, M., Demyttenaere, K., McIntyre, R. S., Widiger, T., & Wittchen, H. U. (2020). The clinical characterization of the adult patient with depression aimed at personalization of management. World Psychiatry, 19(3), 269-293. [CrossRef]

- Makara-Studzińska, M., Somasundaram, S. G., Halicka, J., Madej, A., Leszek, J., Rehan, M., Ashraf, G. M., Gavryushova, L. V., Nikolenko, V. N., & Mikhaleva, L. M. (2021). Suicide and suicide attempts in elderly patients: an epidemiological analysis of risk factors and prevention. Current pharmaceutical design, 27(19), 2231-2236. [CrossRef]

- Maresova, P., Hruska, J., Klimova, B., Barakovic, S., & Krejcar, O. (2020). Activities of daily living and associated costs in the most widespread neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review. Clinical interventions in aging, 1841-1862. [CrossRef]

- Mayo, C. O., Pham, H., Patallo, B., Joos, C. M., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2022). Coping with poverty-related stress: A narrative review. Developmental Review, 64, 101024. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, K. M., Yaffe, K., & Covinsky, K. E. (2002). Cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and functional decline in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50(6), 1045-1050.

- Mekonen, T., Chan, G. C., Connor, J. P., Hides, L., & Leung, J. (2021). Estimating the global treatment rates for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 295, 1234-1242. [CrossRef]

- Merchant, R. A., Chen, M. Z., Wong, B. L. L., Ng, S. E., Shirooka, H., Lim, J. Y., Sandrasageran, S., & Morley, J. E. (2020). Relationship between fear of falling, fear-related activity restriction, frailty, and sarcopenia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(11), 2602-2608.

- Muhammad, T., & Maurya, P. (2022). Social support moderates the association of functional difficulty with major depression among community-dwelling older adults: evidence from LASI, 2017–18. BMC psychiatry, 22(1), 317. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, T., & Meher, T. (2021). Association of late-life depression with cognitive impairment: evidence from a cross-sectional study among older adults in India. BMC geriatrics, 21(1), 364.

- Muncan, B., Walters, S. M., Ezell, J., & Ompad, D. C. (2020). “They look at us like junkies”: influences of drug use stigma on the healthcare engagement of people who inject drugs in New York City. Harm reduction journal, 17, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Nakagomi, A., Shiba, K., Hanazato, M., Kondo, K., & Kawachi, I. (2020). Does community-level social capital mitigate the impact of widowhood & living alone on depressive symptoms?: A prospective, multi-level study. Social Science & Medicine, 259, 113140. [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y., & Loibl, C. (2021). Financial capability and financial planning at the verge of retirement age. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 42(1), 133-150. [CrossRef]

- Nie, X., Li, Y., Li, C., Wu, J., & Li, L. (2021). The association between health literacy and self-rated health among residents of China aged 15–69 years. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 60(4), 569-578. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H., & Lee, H. (2021). Is the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale as useful as the geriatric depression scale in screening for late-life depression? A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 292, 454-463. [CrossRef]

- Peleg, S., & Nudelman, G. (2021). Associations between self-rated health and depressive symptoms among older adults: Does age matter? Social Science & Medicine, 280, 114024. [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka, E., Napierała, P., Podfigurna, A., Męczekalski, B., Smolarczyk, R., & Grymowicz, M. (2020). The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas, 139, 6-11. [CrossRef]

- Sciubba, J. D. (2020). Population aging as a global issue. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies.

- Sellwood, J. A., & Masters, K. L. (2022). Spirals in galaxies. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 60(1), 73-120.

- Skinner, C. J. (2014). Probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling. Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online, 1-5.

- Steptoe, A., & Di Gessa, G. (2021). Mental health and social interactions of older people with physical disabilities in England during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet Public Health, 6(6), e365-e373. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., & Lyu, S. (2020). Social participation and urban-rural disparity in mental health among older adults in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 399-404. [CrossRef]

- Szanto, K., Galfalvy, H., Kenneally, L., Almasi, R., & Dombrovski, A. Y. (2020). Predictors of serious suicidal behavior in late-life depression. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 40, 85-98. [CrossRef]

- Viinikainen, J., Bryson, A., Böckerman, P., Kari, J. T., Lehtimäki, T., Raitakari, O., Viikari, J., & Pehkonen, J. (2022). Does better education mitigate risky health behavior? A mendelian randomization study. Economics & Human Biology, 46, 101134. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Liu, Y., Ji, D., Xie, K., Yang, Y., Zhu, X., Feng, Z., Guo, H., & Wang, B. (2024). The association between functional disability and depressive symptoms among older adults: Findings from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Journal of Affective Disorders, 351, 518-526. [CrossRef]

- Woolrych, R., Sixsmith, J., Fisher, J., Makita, M., Lawthom, R., & Murray, M. (2021). Constructing and negotiating social participation in old age: experiences of older adults living in urban environments in the United Kingdom. Ageing & Society, 41(6), 1398-1420. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. (2021). The mediating and moderating effects of depressive symptoms on the prospective association between cognitive function and activities of daily living disability in older adults. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics, 96, 104480. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y., Ma, M., Wu, W., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., & Tan, X. (2021). Factors associated with depressive symptoms among the elderly in China: structural equation model. International Psychogeriatrics, 33(2), 157-167. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y., Du, Y., Li, X., Ping, W., & Chang, Y. (2023). Physical function, ADL, and depressive symptoms in Chinese elderly: evidence from the CHARLS. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1017689. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Deng, Q., Geng, Q., Tang, Y., Ma, J., Ye, W., Gan, Q., Rehemayi, R., Gao, X., & Zhu, C. (2021). Association of self-rated health with chronic disease, mental health symptom and social relationship in older people. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 14653. [CrossRef]

- Zenebe, Y., Akele, B., W/Selassie, M., & Necho, M. (2021). Prevalence and determinants of depression among old age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of general psychiatry, 20(1), 55. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F., & Yang, W. (2024). Interaction between activities of daily living and cognitive function on risk of depression. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1309401. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Xiong, Y., Yu, Q., Shen, S., Chen, L., & Lei, X. (2021). The activity of daily living (ADL) subgroups and health impairment among Chinese elderly: a latent profile analysis. BMC geriatrics, 21, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y., Wang, J., & Nicholas, S. (2020). Social support and depressive symptoms among family caregivers of older people with disabilities in four provinces of urban China: the mediating role of caregiver burden. BMC geriatrics, 20, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L., Ma, X., & Wang, W. (2021). Relationship between cognitive performance and depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 454-458. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W., Chen, D., Hong, Z., Fan, H., Liu, S., & Zhang, L. (2021). The relationship between health-promoting lifestyles and depression in the elderly: Roles of aging perceptions and social support. Quality of Life Research, 30, 721-728. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).