1. Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a neglected tropical disease caused by parasites of the genus

Leishmania, transmitted to humans through the bite of infected sandflies. Leishmaniasis manifests in three main forms: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral (also known as kala-azar). Cutaneous leishmaniasis is characterized by the appearance of skin ulcers and is responsible for 95% of global cases [

1]. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis affects the mucous membranes of the nose, mouth, and throat, while visceral leishmaniasis is the most severe and can be fatal if untreated, affecting internal organs such as the liver and spleen. A prevalence of 50 000 – 90 000 cases has annually been reported primarily in India, Brazil, and East African countries [

2].

Leishmaniasis disproportionately affects inhabitants residing in poverty, mainly in the tropics and subtropics. It imposes a major health, social, and economic burden on over one billion people across the globe, notably in low-income nations and the most deprived groups in middle-income countries. This complex disease has a substantial devastating impact in terms of morbidity and mortality on people living in the affected countries. Such disadvantaged communities lack timely access to affordable therapy in fragile health systems leaving a considerable number of people severely damaged and disfigured, frequently resulting in social exclusion, discrimination, distress, life-long stigmatization, and serious disability [

2,

3].

The control of leishmaniasis has been complex due to the lack of vaccines, safe and effective drugs; as well as the existence of numerous biological vectors and reservoir hosts with diverse ecological habitats [

2]. The efficacy of currently available drugs varies among species of parasites prevalent in different areas, with each species having a unique clinical presentation and resistance profile [

4]. Side effects and cost also limit present treatment alternatives [

5].

The development of safe and effective antileishmanial vaccines and drugs has been a need for decades. However, the research and development investment needed to bring a new medicine to market has recently been estimated in 1335.9 million USD [

6], figures hardly recoverable with a drug indicated for a disease that primarily affects poor people. In this context, drug repositioning has been identified as an efficient approach for the development of new drugs [

7] and in particular for antileishmanial agents [

8].

Drug repositioning, also known as drug repurposing or drug re-targeting, involves finding new therapeutic applications for existing drugs. This approach can result in significant savings in the development costs of a drug. The main factors contributing to these savings are: 1) Reduction in research and development costs: Since the drug has already gone through the initial discovery and preclinical testing phases, these associated costs and times are saved. 2) Lower risk of failure: Repositioned drugs have already been approved by regulatory agencies for at least one indication, which means their safety and pharmacokinetic profiles are well established. This significantly reduces the risk of failure in the clinical stages. 3) Acceleration of development time: The process of developing new drugs can take 10 to 15 years, while repositioning can reduce this time to 3-5 years, thereby accelerating the availability of the drug for its new indication. 4) Regulatory and clinical trial costs: Although clinical trials are still required to validate the new indication, these are generally less expensive and faster than for a new drug [

7,

9,

10,

11].

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM) are among the many recent attempts of drug repurposing for leishmaniasis. SERM, primarily known for their use in breast cancer, infertility and osteoporosis treatments, have been evaluated for their potential activity against Leishmania spp. parasites. Tamoxifen and raloxifene are SERM that have shown antileishmanial activity.

Tamoxifen inhibits growth of promastigotes of several

Leishmania species

in vitro and reduces viability of intracellular amastigotes [

12,

13]. The antileishmanial activity of tamoxifen has been related to its potential effect on sphingolipid metabolism. Besides, it affects mitochondrial function by inducing alterations in the plasma membrane potential [

14]. In animal models of cutaneous leishmaniasis, tamoxifen reduces lesion growth and the average number of parasites in the skin lesions [

15,

16,

17]. Moreover, the combination of either amphotericin B and tamoxifen or pentavalent antimonial and tamoxifen has an additive and probably synergistic effect

in vivo [

18,

19]. Furthermore, in mouse and hamster models of visceral leishmaniasis, tamoxifen reduces parasite burden in liver and spleen compared to infected, non-treated animals [

20].

In cutaneous leishmaniasis patients, co-administration of oral tamoxifen and systemic pentavalent antimonial (meglumine antimoniate) results in higher cure rates in comparison with the standard scheme of treatment [

21]. More recently, a combination of a single intramuscular dose of pentamidine followed by oral tamoxifen was compared to three intramuscular doses of pentamidine in a randomized, controlled, open-label, non-inferiority clinical trial. Seventy-two percent of patients allocated to the intervention group and 100 % the control group were cured at six months of follow-up. Although a lower cure rate was achieved with the drug combination, it was safe and considered a promising option for populations in remote areas [

22].

Raloxifene has antileishmanial activity

in vitro against several species with 50 % inhibitory concentrations values ranging from 30.2 µM to 38.0 µM against promastigotes and from 8.8 to 16.2 µM against intracellular amastigotes. Besides, treatment of

L. amazonensis – infected BALB/c mice with raloxifene leads to significant decrease in lesion size and parasite burden [

23]. Recent

in silico studies suggest that raloxifene could be an inhibitor of trypanothione synthetase, which is a component of the trypanothione pathway in

Leishmania spp. [

24].

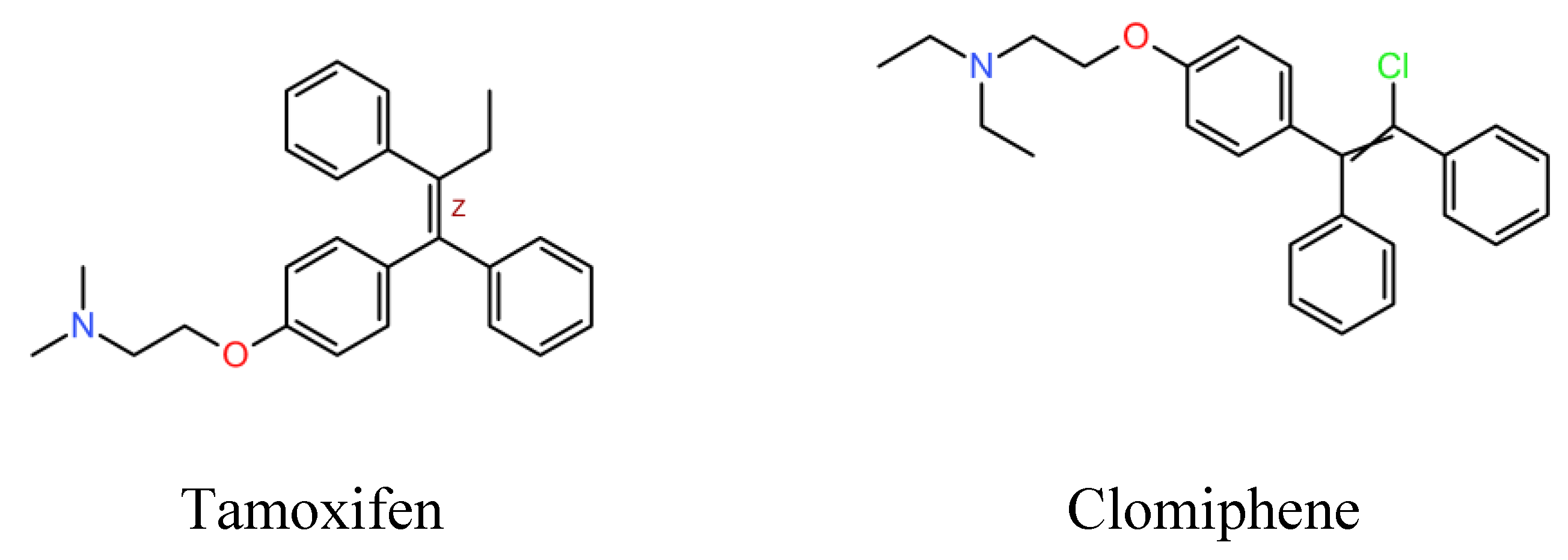

SERM are a family of structurally dissimilar compounds at different stages of pharmaceutical development. Among them, clomiphene, (

Figure 1) is a triphenylethylene derivative structurally similar to tamoxifen.

Clomiphene is a medication primarily used in the treatment of infertility. In women it is indicated to induce ovulation, and in men, to induce spermatogenesis as well as for the treatment of hypogonadism, as a means to stimulate endogenous testosterone production. Clomiphene is a safe oral drug that, due to its structural resemblance to tamoxifen, could be a candidate for repositioning for the treatment of leishmaniasis. To our knowledge, there is no previous report on the antileishmanial activity of clomiphene. Therefore, the aim of the present work was assessing the antileishmanial effect of clomiphene in vitro and in a mouse model of experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Compounds

Tamoxifen and clomiphene (in the form of citrates) were donated by BioCubaFarma (Havana, Cuba) with a purity over 99 %. They were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, SIGMA-ALDRICH, St. Louis, MO, USA) and conserved at 5 °C until. Then they were dissolved in the different culture media, depending on the assay. The maximum concentration of DMSO in the cultures was 0.5 %. Amphotericin B deoxycholate (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), supplied as a 250 µg/mL solution, was used as a positive control.

2.2. Parasites and Cultures

L. amazonensis MHOM/BR/77/LTB0016 reference strain was kindly donated by the Department of Immunology of Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz), Brazil.

L. mexicana MNYC/BZ/62/M379 and

L. major MHOM/IL/81/Friedlin reference strains were kindly donated by Paul A. Bates, Division of Biomedical and Life Sciences, Faculty of Health and Medicine, Lancaster University, United Kingdom. The promastigotes were cultured in medium 199 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), 1% vitamins (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and antibiotics (200 UI/mL penicillin and 200 µg/mL streptomycin). Intracellular amastigote cultures were obtained by infection of primary cultures of mouse peritoneal macrophages with axenic

L. mexicana amastigotes at a ratio of three parasites per macrophage as reported elsewhere [

25]. The cultures were maintained at 37 °C and 5 % CO

2 in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland, UK).

2.3. Animals

Female, 16-18 g, 6-8 weeks old BALB/c mice were supplied by the Animal Models Unit of the Faculty of Medicine, National Autonomous University of México. Mice were housed under controlled environmental conditions (room temperature 22-25 °C, relative humidity 60-65 %, light cycle 12 h light-12 h dark) and were handled by qualified personnel. At the end of the studies, they were sacrificed by CO

2 inhalation. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics in Research Committee and the Internal Committee on the Care and Use of Lab Animals (Code CICUAL 004-CIC-2019). All the experiments were conducted in accordance with the Mexican Regulation [

26] and the Institute of Laboratory Animal Research Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [

27].

2.4. Activity against Promastigotes

The growth inhibition assay was performed according to the procedure of Bodley et al [

28]. Briefly, the promastigotes were cultured in 96-well plates and challenged with serial dilutions of the test (clomiphene and tamoxifen) and control (Amphotericin B) compounds. After 48 h at 26 °C, 20 μL of p-nitrophenyl phosphate (20 mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well and after 3 h at 37 °C the absorbance was read at 405 nm. From the absorbance values and the corresponding concentrations, the mean inhibitory concentrations (IC

50) were estimated by non-linear fitting to the sigmoid Emax equation [

24].

2.5. Cytotoxicity Assay in Mouse Peritoneal Macrophages

Cytotoxicity studies were conducted as described elsewhere [

29]. Briefly, primary cultures of peritoneal macrophages from BALB/c mice were exposed to serial concentrations of the products. After 48 h of incubation at 37 °C and 5 % CO

2, 30 µL of Alamar Blue

TM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Oregon, USA) was added per well. After another 6-8 h of incubation (37 °C and 5 % CO

2), the reduction of Alamar Blue

TM by viable cells was evaluated (Excitation: 485 nm, Emission: 590 nm, Scaling factor: 10/10, Fluoroskan Ascent FL plate reader – Thermo Labsystems, Waltham, MA, USA). The 50 % cytotoxic concentrations (CC

50) were then estimated from the fluorescence values as indicated above.

2.6. Activity against Intracellular Amastigotes

Primary cultures of mouse peritoneal macrophages were infected with axenic amastigotes of

L. mexicana. After 24 h incubation at 37 °C and 5 % CO

2, the medium was replaced by fresh medium containing serial dilutions of the test compounds and incubated for another 48 h under the same conditions. The culture medium was then discarded, replaced with medium 199, and the plates were incubated for another 72 h at 26 °C to allow the surviving amastigotes to transform into promastigotes and replicate [

25]. p-Nitrophenyl phosphate was then added to each well, as described in the promastigote assay, and IC

50 values were estimated as above.

2.7. Electron Microscopy Studies

Promastigotes and intracellular amastigotes of L. mexicana were exposed for 48 h to concentrations of clomiphene from 0.75 µM to 6 µM and then processed for electron microscopy studies. The final concentration of DMSO in the culture media was 0.1 %.

2.7.1. Sample Processing for Transmission Electron Microscopy

Promastigotes were exposed to 1.5 µM to 6 µM clomiphene. Afterwards, they were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove serum from the culture medium and were subsequently fixed in suspension with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS, for 1 h at room temperature (RT). The parasite suspension was washed with PBS at RT and subsequently fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in PBS for 1 h at 4 °C. The promastigotes were washed exhaustively with PBS at RT. Subsequently, they were subjected to a gradual ethanolic dehydration until reaching 100 % ethanol. Afterwards, the parasite suspension was gradually infiltrated with Spurr´s resin (EMS, Hatfield, PA). The parasites were polymerized in plastic molds at 60 °C for 72 h. The blocks were cut on an ultramicrotome (Reichert Jung, Austria). Thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and micrographed on a JEM 1400 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, LTD, Japan).

Intracellular amastigotes were also processed for thin sectioning and transmission electron microscopy. Briefly, macrophages infected and treated with 0.75 µM to 6 µM clomiphene, were washed with PBS, subsequently fixed in 2.5 % glutaraldehyde in PBS, for 30 min, then cells were scraped off from the Petri dish and transferred to Eppendorf tubes. The cell pellet was formed by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 min and the fixation time was continued until completing 1 h. The cell pellet was post-fixed in 1 % OsO4 and dehydrated with increasing concentrations of ethanol and embedded in Spurr´s resin as described above for promastigotes. The ultramicrotome thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and micrographed under a transmission electron microscope.

2.7.2. Sample Processing for Scanning Electron Microscopy

The promastigotes were fixed with glutaraldehyde and osmium tetroxide as indicated above. Subsequently, the parasites were adhered to coverslips previously covered with poly-L-lysine (1 mg/ml). The attached parasites were dehydrated by immersion in increasing concentrations of alcohol. They were subsequently critically dried in a Samdry-780 A equipment (Tousimis Research, Rockville, MD) and evaporated with gold in a Denton Vacuum Desk II evaporator (Moorestown, NJ). The samples were micrographed on a SEM JSM-6510-LV (JEOL LTD, Japan).

2.8. In Vivo Antileishmanial Assay

Female BALB/c mice (8/group) were infected in the foot pads with 10

7 stationary promastigotes of

L. mexicana per mouse. Once the lesions developed (21 days after inoculation), mice were randomly allocated to experimental groups, and oral treatment with tamoxifen [

17] or clomiphene (20 mg/kg, every 24 h, dissolved in isotonic saline solution) was started. One group was treated with amphotericin B as reported elsewhere (7.5 mg/kg, every other day, 7 doses) [

30], and one group did not receive any treatment (control group). The lesions were measured weekly for 4 weeks by using a Vernier caliper (Kroeplin, Längenmesstechnick, error 0.05 mm); then mice were sacrificed, the lesions were excised and weighted, and the parasite load in the lesions of five mice per group were determined by the limiting dilution assay [

31].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Results of the

in vitro studies were expressed as means ± standard deviations but were not statistically compared due to the reduced number of assays (N=3). The evolution of lesion size over time was analyzed by repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Fisher´s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. Lesion weights were compared by ANOVA and Dunnet´s test (versus non-treated control group). Parasite loads were compared by Kruskal-Wallis test and the Distribution-free multiple comparisons test as post-hoc. Values of p under 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analysis were conducted by using GraphPad Prism software (Version 8.0.2,

https://www.graphpad.com/)

3. Results

In vitro testing of tamoxifen and clomiphene against promastigotes evidenced that clomiphene was near twice more active than tamoxifen for the three tested Leishmania species (

Table 1): The IC

50 values were in the range of 1.7 µM to 3.3 µM for clomiphene, while for tamoxifen they were from 2.9 µM to 6.4 µM. Cytotoxicity for mouse peritoneal macrophages and in vitro activity against intracellular L. mexicana amastigotes were comparable for both compounds. However, the selectivity index of clomiphene was slightly higher than the one of tamoxifen. IC

50 values of amphotericin B against the promastigote and amastigote stages of Leishmania spp. were in the range reported for this drug

[32,33]. An exact estimate of amphotericin B CC

50 could not be obtained because it was over the maximum concentration tested, which was achieved with the presentation of amphotericin B used (250 µg/mL) after proper dilution in the culture medium. Nevertheless, the estimate (over 6.7 µM) agreed with Kaiser´s previous report of 23.1 µM

[33].

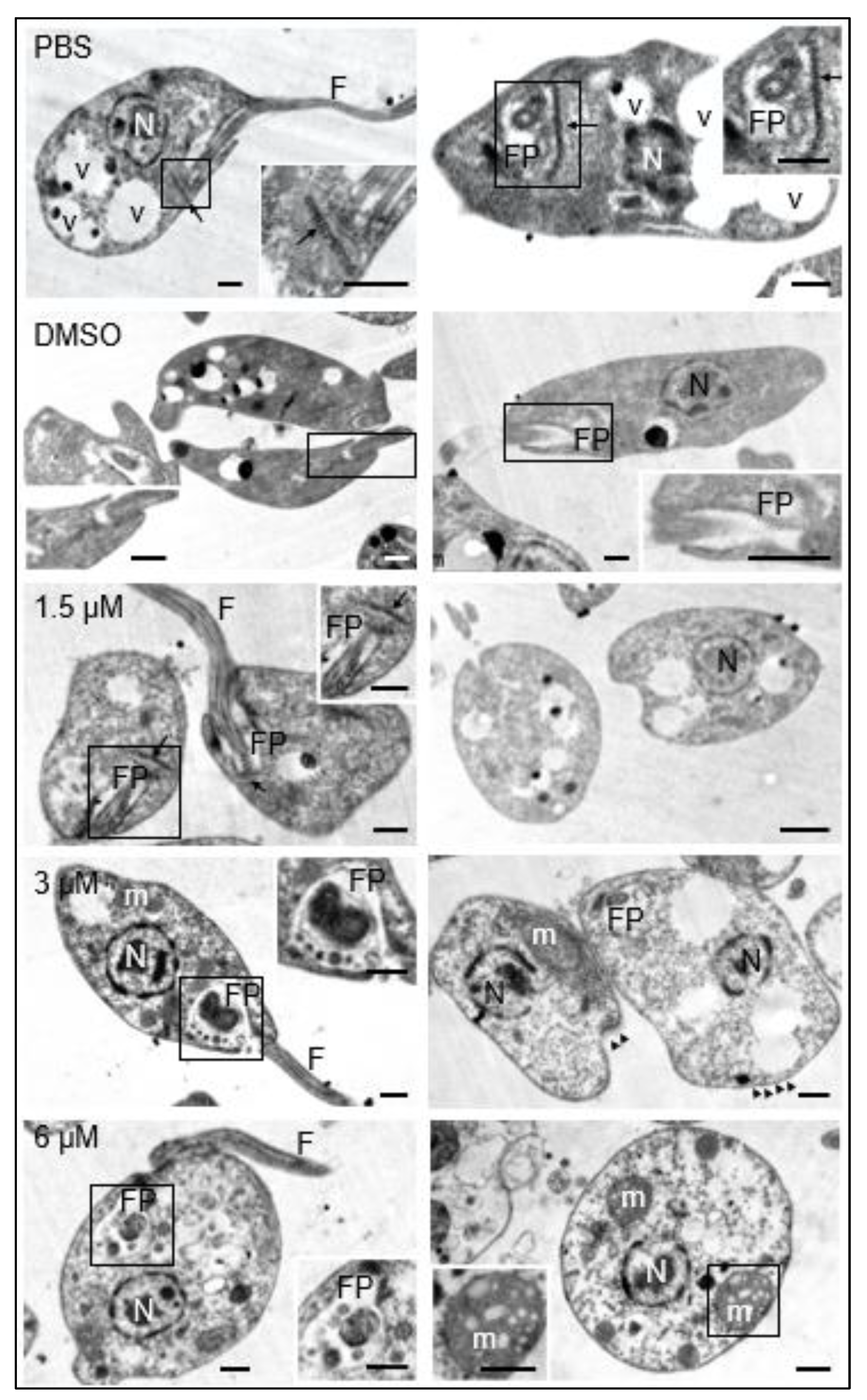

Under the transmission electron microscopy, it was observed that the promastigotes maintained in culture medium containing 0.1 % DMSO did not show structural changes with respect to those maintained in culture medium with the equivalent volume of PBS. These results guaranteed that any changes observed in parasites treated with the test compound were due to its effect and not to DMSO used as a cosolvent. The presence of the nucleus, flagellum, flagellar pocket, kinetoplast, dense granules and cytoplasmic vesicles was easily distinguishable in both cases (

Figure 2, PBS, DMSO).

The exposure of promastigotes to different concentrations of clomiphene resulted in gradual changes in the morphology of various parasite structures as the compound concentration increased. At 1.5 µM clomiphene, swelling of the body of the promastigote began to be detected. Although some parasites presented flagella inserted in the flagellar pockets with presence of apparent normal kinetoplasts, many of them showed ovoid shapes with absence of flagella (

Figure 2, 1.5 µM). When promastigotes were treated with 3 µM clomiphene, deformed swollen flagellar pockets containing swollen dense granules of different sizes were detected (

Figure 2, 3 µM). In this condition, kinetoplasts were not observed. The flagellum was partially preserved and with an altered association with the flagellar pocket. Mitochondrion was severely deformed and swollen. The cytoplasm showed dense aggregates and some extrusion of its contents. However, the nucleus did not show any apparent morphological alterations. At the concentration of 6 µM, all the promastigotes were evidently swollen with loss of their typical elongated shape (

Figure 2, 3 µM). It was still possible to observe the flagellar pocket although its content was extruded and showed dense bodies of various sizes. Although it was not possible to visualize the part of the flagellum that is inserted into the flagellar pocket, flagella laterally associated with the deformed parasites were observed. Mitochondrion was evidently swollen and highly dense, with disorganized and swollen mitochondrial cristae. The plasma membrane was apparently intact; however, some parasites were found in an evident process of cell lysis. Dense cytoplasmic granules with abundant vesicles of different sizes were also observed. Submembrane microtubules were not affected by clomiphene treatment even at the highest concentration tested (

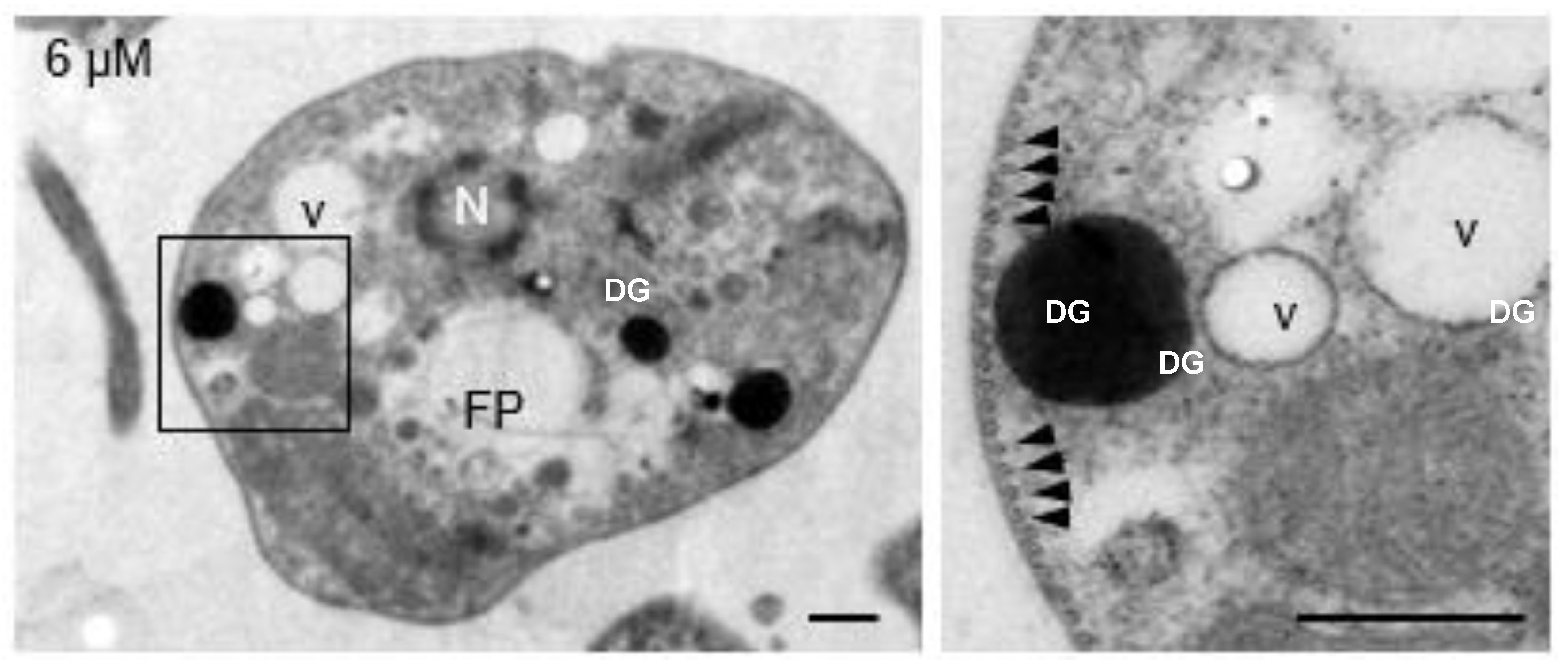

Figure 3).

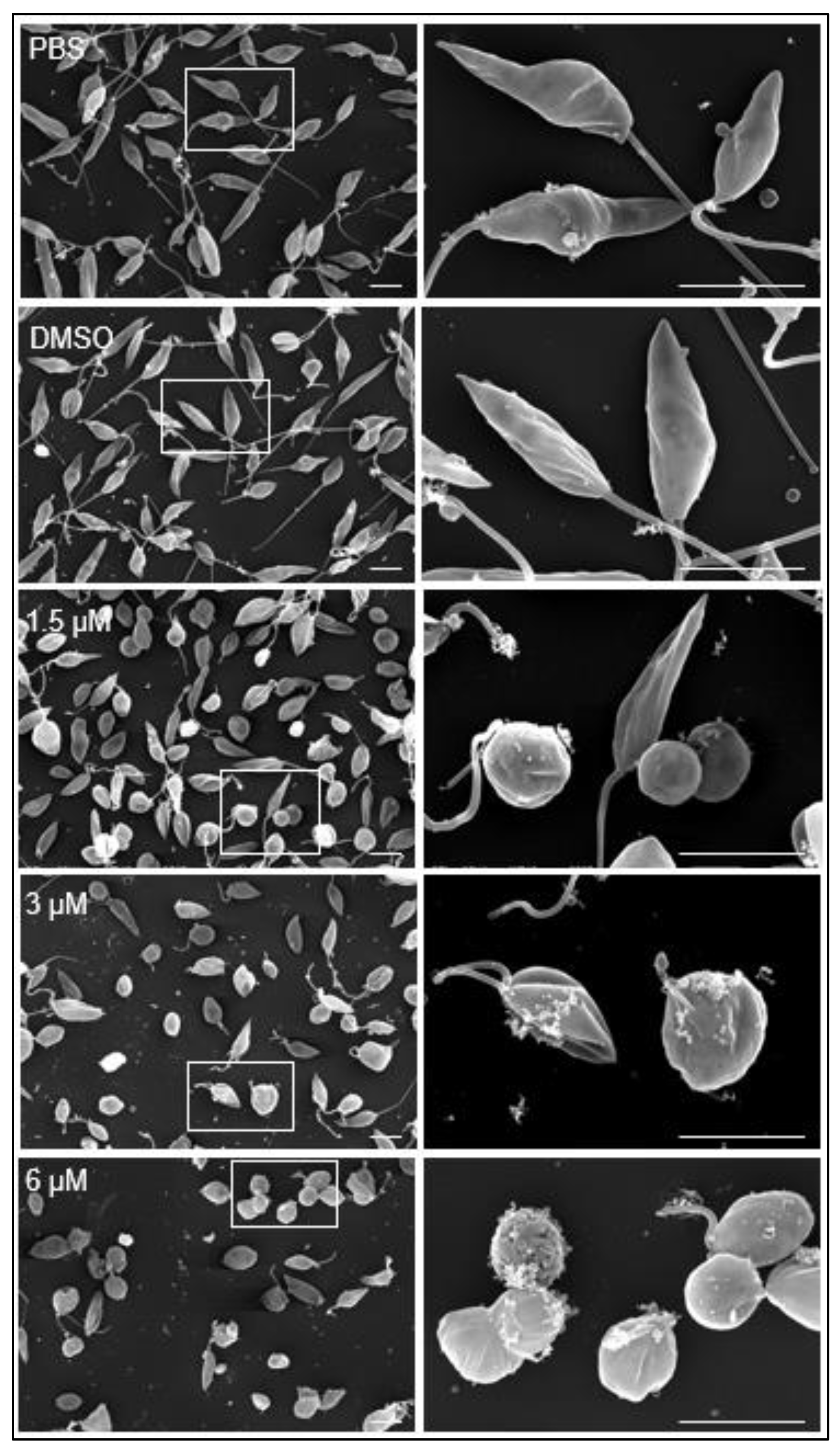

Additionally, the morphology of the promastigotes was analyzed under scanning electron microscopy. In culture medium containing PBS or DMSO diluted in PBS. Promastigotes showed the typical elongated fusiform shape with one flagellum and cytoplasmic vesicles (v) associated with the plasma membrane (

Figure 4, PBS, DMSO).

At 1.5 µM clomiphene (

Figure 4, 1.5 µM), two populations of parasites were detected, one that maintained their apparently normal cell shape with elongated flagella and other population of parasites in evident deformation, with an ovoid or spherical shape that still retained flagella but with atypical folds. At 3 µM clomiphene, most parasites were misshapen and had a spheroidal appearance. All parasites lacked flagella or had very short flagella. Parasites that still retained their elongated shape had a short flagellum attached, no more than 500 nm in length. Additionally, numerous vesicular aggregates, associated with a cottony material (

Figure 4, 3 µM), were observed in association with the plasma membrane.

Most promastigotes exposed to 6 µM clomiphene (

Figure 4, 6 µM) were deformed and lacked flagellum, while only a few showed a short flagellum. The presence of vesicular aggregates and cottony material on the external membrane of the parasites was abundant. Eventually, destroyed parasites were found in the cultures.

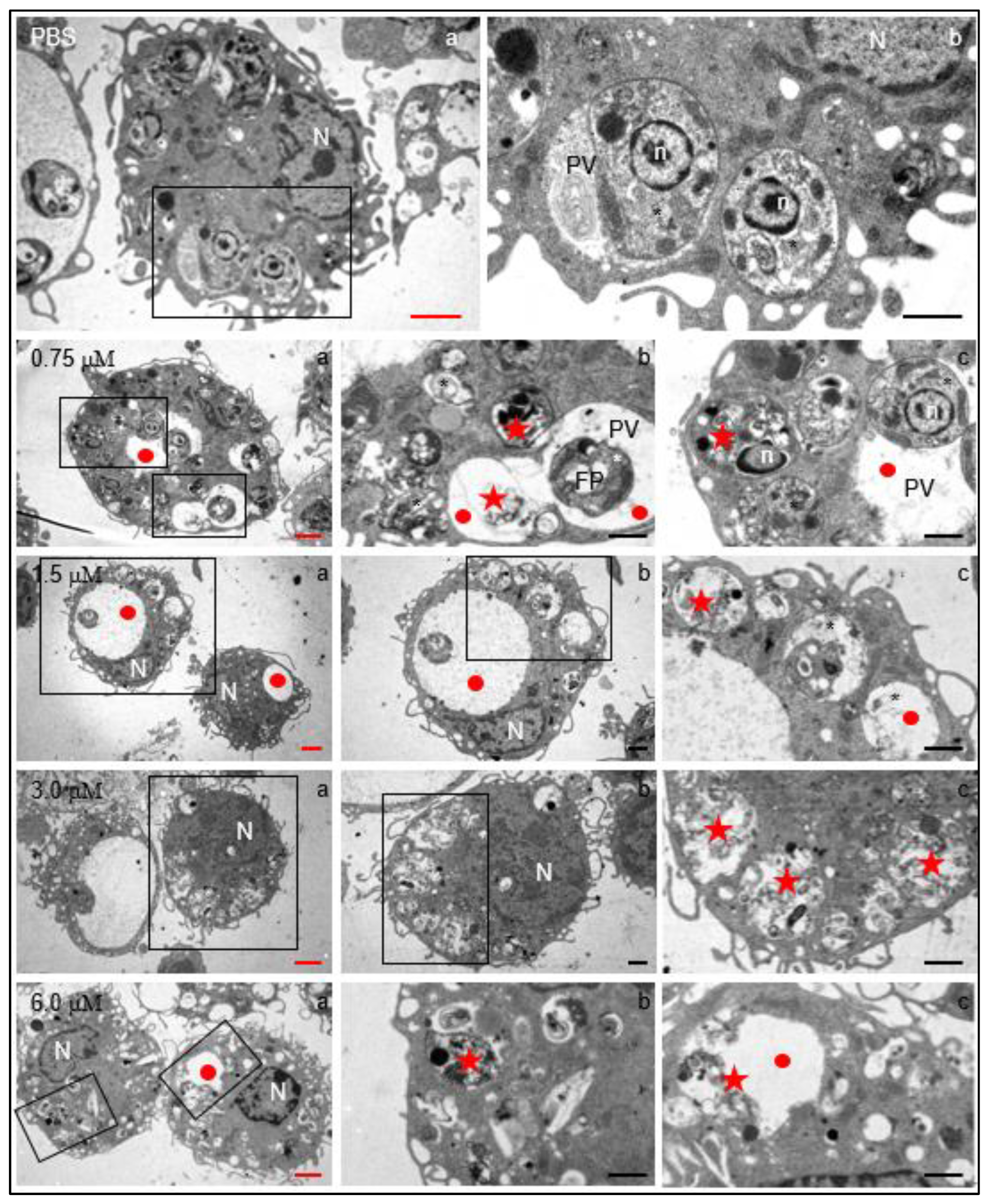

In order to determine whether clomiphene had the capacity to affect intracellular parasites located inside the parasitophorous vacuole without damaging the host cell, primary cultures of mouse peritoneal macrophages were infected with L. mexicana amastigotes and subsequently exposed to 0.75 µM – 6.0 µM clomiphene. As controls, infected macrophages were cultured in medium containing either PBS or 0.1 % DMSO (diluted in PBS), as previously explained for promastigotes.

Regardless of clomiphene concentration, infected macrophages were apparently normal in terms of nuclear morphology, presence of mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and several filopoidal-type prolongations of the plasma membrane (

Figure 5). Moreover, in control cultures, the parasites were found inside the parasitophorous vacuole, showing intact subcellular parasite structures such as the nucleus, mitochondrion and dense granules. Also, vesicular structures were identified in the intravacuolar space.

Several evident changes were found in infected macrophages exposed to 0.75 µM clomiphene, changes that increased in severity as the concentration of clomiphene augmented (

Figure 5). Among the most evident alterations, an enlargement of the parasitophorous vacuoles which contained membranous and vesicular components was found. Additionally, most of the intravacuolar parasites showed evident structural damage from 0.75 µM concentration. At 3 µM and 6 µM clomiphene, intact parasites were no longer observed and only parasitophorous vacuoles with parasitic detritus were found. Additionally, macrophages showed abundant membrane shunts and cytoplasmic vesicles. Although the macrophages contained destroyed intracellular parasites, the cells were not affected in their integrity nor were they under a process of necrosis or cell death.

In summary, the exposure of parasites to clomiphene caused evident morphological changes as well as structural alterations of the flagellar pocket, mitochondrion, flagellar length, and loss of cytoplasm. Interestingly, the submembrane microtubules were not affected in their arrangement and integrity. In this sense, clomiphene did not seem to affect the parasite cytoskeleton, but it did affect the organelles involved in its metabolism, thus compromising viability. Clomiphene, at all the tested concentrations, destroyed intracellular amastigotes residing within the parasitophorous vacuole. On the contrary, macrophages were apparently not affected by the compound in their viability or cell integrity, a fact that supports the selective antileishmanial effect of clomiphene.

In vivo antileishmanial assay

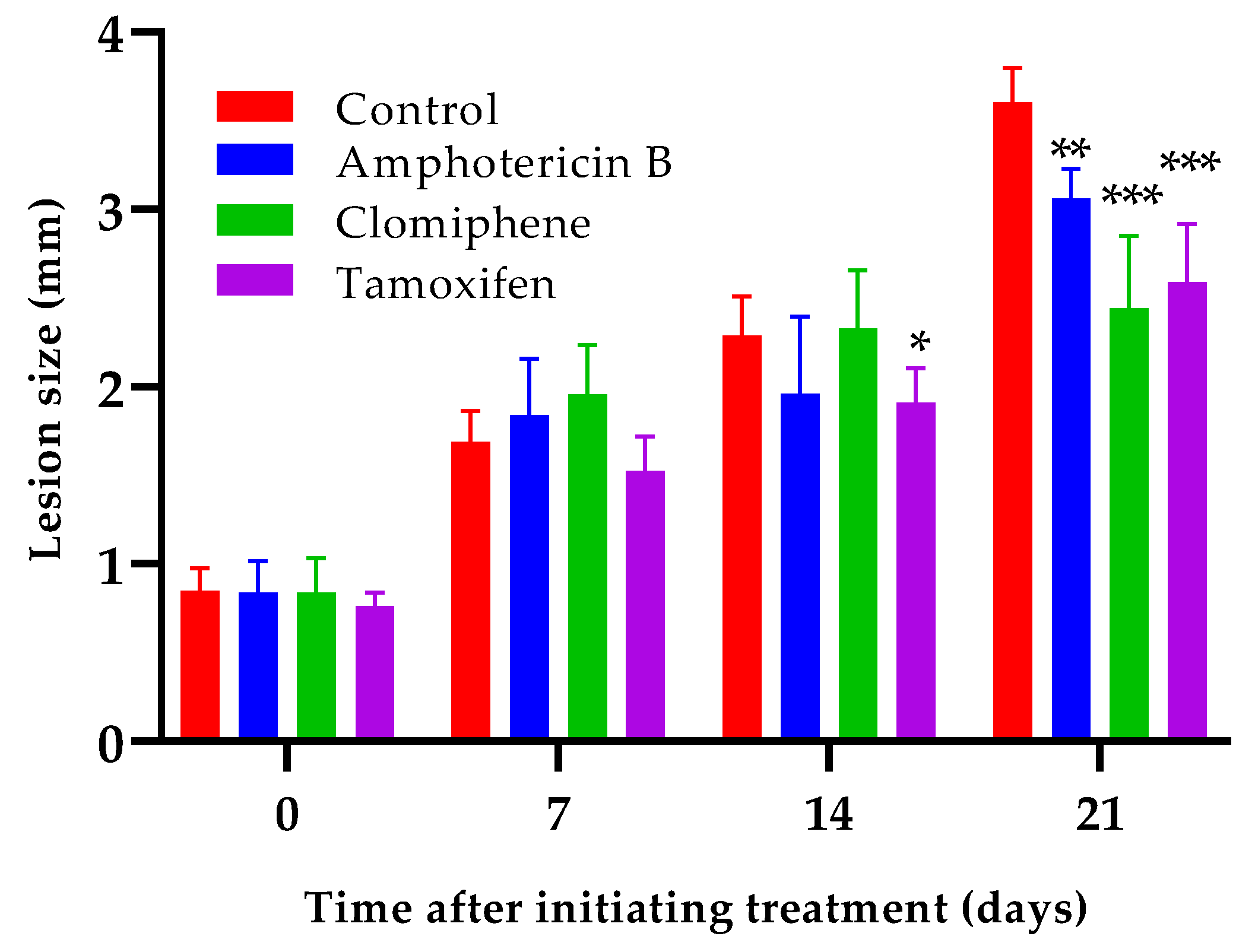

Oral administration of either clomiphene or tamoxifen at 20 mg/kg by oral route reduced lesion growth compared to non-treated infected control mice (

Figure 6). Statistically significant differences (p< 0.001) between the size of the lesions of any of the treated groups and those of the control mice were evident one week after completing treatment (day 21 after the start of treatment). Interestingly, the lesion size of mice treated with either clomiphene or tamoxifen were smaller (p= 0.037 for clomiphene and p= 0.050 for tamoxifen) than those of amphotericin B treated mice at day 21.

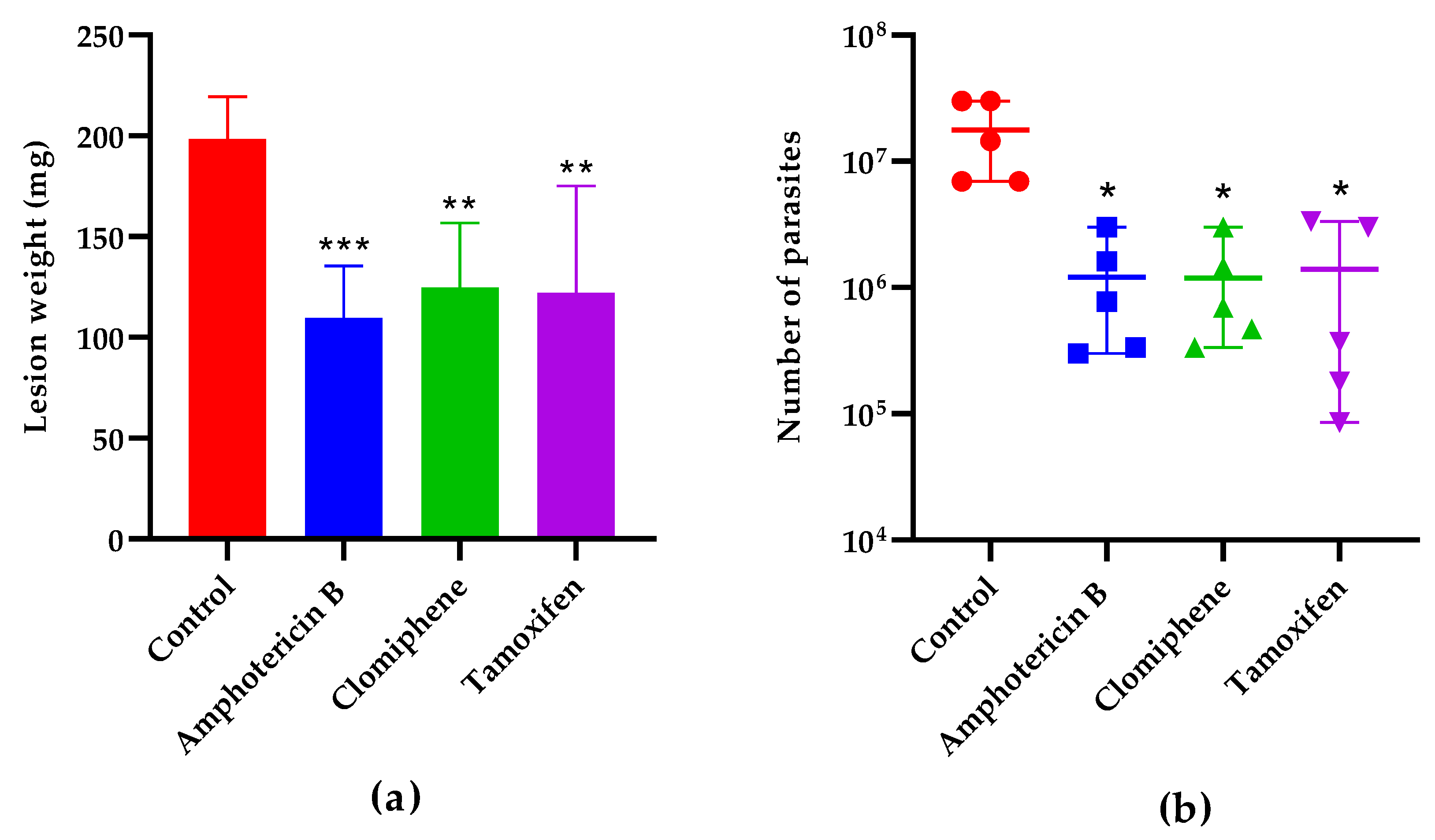

The lesion weight one week after the end of treatment (

Figure 7a) was also statistically smaller in mice treated with either clomiphene (p= 0.0043), tamoxifen (p= 0.0031), or the reference drug amphotericin B (p= 0.0007) compared to non-treated controls. The number of parasites in the lesions was also reduced in treated mice compared to controls (

Figure 7b). Notably, the lesion weight and the parasite load were comparable (p> 0.05) in mice treated with clomiphene, tamoxifen and amphotericin B.

4. Discussion

SERM, and triphenylethylene derivatives in particular, are considered a privileged family of compounds, since they have shown activity against bacteria, fungi, viruses and parasites, besides their primary indications as estrogen modulators [

34]. Despite of the variety of SERM partially or fully developed as drugs, only two of them, tamoxifen and raloxifene, have been tested for their potential as antileishmanial agents.

In the present work, another SERM, clomiphene, demonstrated leishmanicide activity against promastigotes of three Leishmania species and against intracellular L. mexicana amastigotes, with IC50 values slightly lower than those of tamoxifen tested in parallel. Selectivity index of clomiphene was also slightly better than that of tamoxifen and the activity in a mouse model of experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis by L. mexicana was similar for both compounds.

Electron microscopy studies confirmed the selective leishmanicide activity of clomiphene, since morphological changes of the amastigotes were observed at concentrations as low as 0.75 µM, but macrophages, the host cells, remained unaltered at the highest tested concentration (6.0 µM). Both, tamoxifen and raloxifene, alter mitochondrial function and morphology and eventually lead to cell death without primarily affecting cell membrane permeability and integrity [

19,

35]. Similarly, in cultures exposed to clomiphene, amastigotes with severely affected organelles (including mitochondrion) with apparently intact cytoplasm membrane were observed.

Regarding the antileishmanial mechanism of action of tamoxifen, it induces alkalinization of the phagolysosome [

15]. The acidic pH in normally functioning phagolysosomes is the proper environment for the intracellular transformation of

Leishmania promastigotes into amastigotes, their proliferation and survival; therefore, the tamoxifen-induced alkalinization of the phagolysosome reduces amastigote multiplication and viability. Tamoxifen also interferes in sphingolipid biosynthesis of

Leishmania [

36].

Sphingolipids are an essential component of the cell membrane of

Leishmania and are important mediators of cell signaling and control several biological processes [

37,

38,

39]. Inositol phosphorylceramide is the main sphingolipid in

Leishmania, but is absent in mammalian cells, resulting in an efficient antileishmanial drug target [

39,

40]. Moreover, tamoxifen causes mitochondrial damage with loss of membrane potential, and also leads to plasma membrane depolarization without general membrane disruption or permeabilization [

35]. Therefore, the effect of tamoxifen on

Leishmania is mediated, in part, by disorder in the parasite’s membranes, which triggers a series of lethal events [

35,

41].

On the other hand, raloxifene depolarizes mitochondrial and plasma membrane potentials of

Leishmania spp., resulting in functional disorders on the plasma membrane and the mitochondrion, which culminate in cell death. Notably, treated parasites display autophagosomes and mitochondrial damage while the plasma membrane remains continuous [

23]. Considering the similarity of the ultrastructural effects induced by tamoxifen and raloxifene with those caused by clomiphene, the mechanism of action of clomiphene probably shares at least some characteristics with that of these two other compounds.

Tamoxifen and clomiphene, although used in different contexts, have some common side effects due to their action on estrogen receptors. They both can cause hot flashes, nausea, headaches and cataracts; affect mood; and have effects on the reproductive system (tamoxifen can cause menstrual changes and clomiphene can induce multiple ovulation). However, tamoxifen has serious risks such as thrombosis, strokes, endometrial cancer and hepatotoxicity, while clomiphene can cause ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and multiple pregnancies. Tamoxifen is more associated with long-term adverse effects such as cardiovascular risks and endometrial cancer, while adverse effects of clomiphene are usually more immediate and related to ovulation and fertility. Clomiphene and tamoxifen are generally considered safe medications; however, the safety profile of clomiphene (mainly with respect to serious unwanted effects) is more favorable than that of tamoxifen [

42,

43].

5. Conclusions

Clomiphene showed in vitro and in vivo activity comparable to that of tamoxifen. Likewise, electron microscopy studies demonstrated that clomiphene has a selective leishmanicide effect, since it causes concentration-dependent structural changes in the parasite without affecting the host cell. Considering that the safety profile of clomiphene is more favorable than that of tamoxifen, repurposing clomiphene as an antileishmanial agent could even be a more attractive option. Results presented in this paper and those of previous studies support future research on the antileishmanial potential of selective estrogen receptor modulators.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SSR, AREM and MMAG; methodology, SSR, AREM, RMF, NMD, LMF; formal analysis, SSR; investigation, SSR, RMF, NMD, LMF, MEMC, FAG, LALE, DASA, OPO; resources, AREM, RMF, MMAG; data curation, SSR; writing—original draft preparation, SSR; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, SSR, AREM, MMAG; project administration, MMAG; funding acquisition, MMAG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

MMAG thanks SEP-CONAHCYT México [grant # 284018] and DGAPA-PAPIIT [grant # 212422] for funding this work. SSR was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the DGAPA/UNAM program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experimental protocol was approved by Ethics in Research Committee and the Internal Committee on the Care and Use of Lab Animals of the Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (Code CICUAL 004-CIC-2019).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ejov, M.; Dagne, D. Strategic Framework for Leishmaniasis Control in the WHO European Region 2014-2020. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe.; 2014; https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/329477 (accessed on 20/7/2024).

- Bamorovat, M.; Sharifi, I.; Khosravi, A.; Aflatoonian, M.R.; Agha Kuchak Afshari, S.; Salarkia, E.; Sharifi, F.; Aflatoonian, B.; Gharachorloo, F.; Khamesipour, A.; et al. Global Dilemma and Needs Assessment Toward Achieving Sustainable Development Goals in Controlling Leishmaniasis. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2024, 14, 22-34. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Shmueli, M.; Ben-Shimol, S. Review of Leishmaniasis Treatment: Can We See the Forest Through the Trees? Pharmacy 2024, 12 (1), 30. [CrossRef]

- das Neves, M.A.; do Nascimento, J.R.; Maciel-Silva, V.L.; dos Santos, A.M.; Junior, J. de J.G.V.; Coelho, A.J.S.; Lima, M.I.S.; Pereira, S.R.F.; da Rocha, C.Q. Anti-Leishmania Activity and Molecular Docking of Unusual Flavonoids-Rich Fraction from Arrabidaea Brachypoda (Bignoniaceae). Mol Biochem Parasitol 2024, 259, 111629. [CrossRef]

- Wouters, O.J.; McKee, M.; Luyten, J. Estimated Research and Development Investment Needed to Bring a New Medicine to Market, 2009-2018. JAMA 2020, 323, 844. [CrossRef]

- Scannell, J.W.; Blanckley, A.; Boldon, H.; Warrington, B. Diagnosing the Decline in Pharmaceutical R&D Efficiency. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012, 11, 191–200. [CrossRef]

- Charlton, R.L.; Rossi-Bergmann, B.; Denny, P.W.; Steel, P.G. Repurposing as a Strategy for the Discovery of New Anti-Leishmanials: The-State-of-the-Art. Parasitology 2018, 145, 219–236. [CrossRef]

- Sleigh, S.H.; Barton, C.L. Repurposing Strategies for Therapeutics. Pharmaceut Med 2010, 24, 151–159. [CrossRef]

- Nosengo, N. Can You Teach Old Drugs New Tricks? Nature 2016, 534, 314–316. [CrossRef]

- Ashburn, T.T.; Thor, K.B. Drug Repositioning: Identifying and Developing New Uses for Existing Drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2004, 3, 673–683. [CrossRef]

- Miguel, D.C.; Yokoyama-Yasunaka, J.K.U.; Andreoli, W.K.; Mortara, R.A.; Uliana, S.R.B. Tamoxifen Is Effective against Leishmania and Induces a Rapid Alkalinization of Parasitophorous Vacuoles Harbouring Leishmania (Leishmania) Amazonensis Amastigotes. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2007, 60, 526–534. [CrossRef]

- Doroodgar, M.; Delavari, M.; Doroodgar, M.; Abbasi, A.; Taherian, A.A.; Doroodgar, A. Tamoxifen Induces Apoptosis of Leishmania Major Promastigotes in Vitro. Korean J Parasitol 2016, 54, 9–14. [CrossRef]

- Zewdie, K.A.; Hailu, H.G.; Ayza, M.A.; Tesfaye, B.A. Antileishmanial Activity of Tamoxifen by Targeting Sphingolipid Metabolism: A Review. Clin Pharmacol 2022, 14, 11–17. [CrossRef]

- Miguel, D.C.; Zauli-Nascimento, R.C.; Yokoyama-Yasunaka, J.K.U.; Katz, S.; Barbieri, C.L.; Uliana, S.R.B. Tamoxifen as a Potential Antileishmanial Agent: Efficacy in the Treatment of Leishmania Braziliensis and Leishmania Chagasi Infections. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2008, 63, 365–368. [CrossRef]

- Miguel, D.C.; Yokoyama-Yasunaka, J.K.U.; Uliana, S.R.B. Tamoxifen Is Effective in the Treatment of Leishmania Amazonensis Infections in Mice. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2008, 2, e249. [CrossRef]

- Eissa, M.M.; Amer, E.I.; El Sawy, S.M.F. Leishmania Major: Activity of Tamoxifen against Experimental Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Exp Parasitol 2011, 128, 382–390. [CrossRef]

- Trinconi, C.T.; Reimão, J.Q.; Bonano, V.I.; Espada, C.R.; Miguel, D.C.; Yokoyama-Yasunaka, J.K.U.; Uliana, S.R.B. Topical Tamoxifen in the Therapy of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Parasitology 2018, 145, 490–496. [CrossRef]

- Trinconi, C.T.; Reimão, J.Q.; Yokoyama-Yasunaka, J.K.U.; Miguel, D.C.; Uliana, S.R.B. Combination Therapy with Tamoxifen and Amphotericin B in Experimental Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 2608–2613. [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.F.; Reis, L.E.S.; Machado, M.G.C.; Dophine, D.D.; de Andrade, V.R.; de Lima, W.G.; Andrade, M.S.; Vilela, J.M.C.; Reis, A.B.; Pound-Lana, G.; et al. Repositioning of Tamoxifen in Surface-Modified Nanocapsules as a Promising Oral Treatment for Visceral Leishmaniasis. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1061. [CrossRef]

- Machado, P.R.L.; Ribeiro, C.S.; França-Costa, J.; Dourado, M.E.F.; Trinconi, C.T.; Yokoyama-Yasunaka, J.K.U.; Malta-Santos, H.; Borges, V.M.; Carvalho, E.M.; Uliana, S.R.B. Tamoxifen and Meglumine Antimoniate Combined Therapy in Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Patients: A Randomised Trial. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2018, 23, 936–942. [CrossRef]

- Pennini, S.N.; de Oliveira Guerra, J.A.; Rebello, P.F.B.; Abtibol-Bernardino, M.R.; de Castro, L.L.; da Silva Balieiro, A.A.; de Oliveira Ferreira, C.; Noronha, A.B.; dos Santos da Silva, C.G.; Leturiondo, A.L.; et al. Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis with a Sequential Scheme of Pentamidine and Tamoxifen in an Area with a Predominance of Leishmania (Viannia) Guyanensis : A Randomised, Non-inferiority Clinical Trial. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2023, 28, 871–880. [CrossRef]

- Reimão, J.Q.; Miguel, D.C.; Taniwaki, N.N.; Trinconi, C.T.; Yokoyama-Yasunaka, J.K.U.; Uliana, S.R.B. Antileishmanial Activity of the Estrogen Receptor Modulator Raloxifene. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014, 8, e2842. [CrossRef]

- Vemula, D.; Mohanty, S.; Bhandari, V. Repurposing of Food and Drug Admnistration (FDA) Approved Library to Identify a Potential Inhibitor of Trypanothione Synthetase for Developing an Antileishmanial Agent. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27602. [CrossRef]

- Sifontes-Rodríguez, S.; Escalona-Montaño, A.R.; Sánchez-Almaraz, D.A.; Pérez-Olvera, O.; Aguirre-García, M.M. Detergent-Free Parasite Transformation and Replication Assay for Drug Screening against Intracellular Leishmania Amastigotes. J Microbiol Methods 2023, 215, 106847. [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Agricultura, G.D.R.P. y A. (SAGARPA) NOM-062-ZOO-1999_220801; México, 2001; p. 107;.

- National Research Council (U.S.). Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.; Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals; National Academies Press, 2011; ISBN 9780309154000.

- Bodley, A.L.; Mcgarry, M.W.; Shapiro, T.A. Drug Cytotoxicity Assay for African Trypanosomes and Leishmania Species. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1995, 172(4), 1157-1159.

- Sifontes-Rodríguez, S.; Mollineda-Diogo, N.; Monzote-Fidalgo, L.; Escalona-Montaño, A.R.; Escario García-Trevijano, J.A.; Aguirre-García, M.M.; Meneses-Marcel, A. In Vitro and In Vivo Antileishmanial Activity of Thioridazine. Acta Parasitol 2024, 69, 324–331. [CrossRef]

- Sifontes-Rodríguez, S.; Chaviano-Montes de Oca, C.S.; Monzote-Fidalgo, L.; Meneses-Gómez, S.; Mollineda-Diogo, N.; Escario-García-Trevijano, J.A. Amphotericin B Is Usually Underdosed in the Treatment of Experimental Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Ars Pharmaceutica 2022, 63, 253–262. [CrossRef]

- Titus, R.G.; Marchand, M.; Boon, T.; Louis, J.A. A Limiting Dilution Assay for Quantifying Leishmania Major in Tissues of Infected Mice. Parasite Immunol 1985, 7, 545–555. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, B.A.; Coser, E.M.; Saborito, C.; Yamashiro-Kanashiro, E.H.; Lindoso, J.A.L.; Coelho, A.C. In Vitro Miltefosine and Amphotericin B Susceptibility of Strains and Clinical Isolates of Leishmania Species Endemic in Brazil That Cause Tegumentary Leishmaniasis. Exp Parasitol 2023, 246, 108462. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, M.; Mäser, P.; Tadoori, L.P.; Ioset, J.-R.; Brun, R. Antiprotozoal Activity Profiling of Approved Drugs: A Starting Point Toward Drug Repositioning. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0135556. [CrossRef]

- Montoya, M.C.; Krysan, D.J. Repurposing Estrogen Receptor Antagonists for the Treatment of Infectious Disease. mBio 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Reimão, J.Q.; Uliana, S.R.B. Tamoxifen Alters Cell Membrane Properties in Leishmania Amazonensis Promastigotes. Parasitol Open 2018, 4, e6. [CrossRef]

- Costa Filho, A.V. da; Lucas, Í.C.; Sampaio, R.N.R. Estudo Comparativo Entre Miltefosina Oral e Antimoniato de N-Metil Glucamina Parenteral No Tratamento Da Leishmaniose Experimental Causada Por Leishmania (Leishmania) Amazonensis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2008, 41, 424–427. [CrossRef]

- Morad, S.A.F.; Tan, S.-F.; Feith, D.J.; Kester, M.; Claxton, D.F.; Loughran, T.P.; Barth, B.M.; Fox, T.E.; Cabot, M.C. Modification of Sphingolipid Metabolism by Tamoxifen and N-Desmethyltamoxifen in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia—Impact on Enzyme Activity and Response to Cytotoxics. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2015, 1851, 919–928. [CrossRef]

- Morad, S.A.F.; Cabot, M.C. Tamoxifen Regulation of Sphingolipid Metabolism—Therapeutic Implications. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2015, 1851, 1134–1145. [CrossRef]

- Landoni, M.; Piñero, T.; Soprano, L.L.; Garcia-Bournissen, F.; Fichera, L.; Esteva, M.I.; Duschak, V.G.; Couto, A.S. Tamoxifen Acts on Trypanosoma Cruzi Sphingolipid Pathway Triggering an Apoptotic Death Process. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 516, 934–940. [CrossRef]

- Trinconi, C.T.; Miguel, D.C.; Silber, A.M.; Brown, C.; Mina, J.G.M.; Denny, P.W.; Heise, N.; Uliana, S.R.B. Tamoxifen Inhibits the Biosynthesis of Inositolphosphorylceramide in Leishmania. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2018, 8, 475–487. [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu Zewdie, K.; Gebregergs Hailu, H.; Altaye Ayza, M.; Amare Tesfaye, B. Antileishmanial Activity of Tamoxifen by Targeting Sphingolipid Metabolism: A Review. Clinical Pharmacology: Advances and Applications 2022, 14, 11-17. [CrossRef]

- Drugs.com Clomiphene Side Effects: Common, Severe, Long Term. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/sfx/clomiphene-side-effects.html (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Drugs.com Tamoxifen Side Effects: Common, Severe, Long Term. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/sfx/tamoxifen-side-effects.html (accessed on 27 May 2024).

Figure 2.

Effects of clomiphene on L. mexicana promastigotes visualized by transmission electron microscopy. The micrographs in the left column correspond to low magnification images to show the general structure of promastigotes. The flagellar pockets were framed and magnified to show the changes in these structures. In the right insert of figure of 6 µM, the structure of a mitochondrion is shown as well as its respective amplification (insert at bottom left). N, nucleus; FP, flagellar pocket; F, flagellum; m, mitochondrion; v, vesicles; kinetoplast (arrow), microtubules (arrowheads). Scale bar = 500 nm.

Figure 2.

Effects of clomiphene on L. mexicana promastigotes visualized by transmission electron microscopy. The micrographs in the left column correspond to low magnification images to show the general structure of promastigotes. The flagellar pockets were framed and magnified to show the changes in these structures. In the right insert of figure of 6 µM, the structure of a mitochondrion is shown as well as its respective amplification (insert at bottom left). N, nucleus; FP, flagellar pocket; F, flagellum; m, mitochondrion; v, vesicles; kinetoplast (arrow), microtubules (arrowheads). Scale bar = 500 nm.

Figure 3.

Clomiphene did not affect the integrity of submembrane microtubules. Intact submembrane microtubules (arrowheads) were observed in promastigotes exposed to 6 µM clomiphene. N, nucleus; FP, flagellar pocket; DG, dense granule; v, vesicle. Scale bar = 500 nm.

Figure 3.

Clomiphene did not affect the integrity of submembrane microtubules. Intact submembrane microtubules (arrowheads) were observed in promastigotes exposed to 6 µM clomiphene. N, nucleus; FP, flagellar pocket; DG, dense granule; v, vesicle. Scale bar = 500 nm.

Figure 4.

Effect of clomiphene on L. mexicana promastigotes treated with clomiphene. Images of scanning electron microscopy on the left side were obtained at low magnification, while on their right side are magnifications of the areas delimited by rectangular frames. Arrows, cells with normal shape; *, deformed parasites; F, flagellum; VA, vesicular aggregates; v, vesicles. Scale bar= 500 nm.

Figure 4.

Effect of clomiphene on L. mexicana promastigotes treated with clomiphene. Images of scanning electron microscopy on the left side were obtained at low magnification, while on their right side are magnifications of the areas delimited by rectangular frames. Arrows, cells with normal shape; *, deformed parasites; F, flagellum; VA, vesicular aggregates; v, vesicles. Scale bar= 500 nm.

Figure 5.

Structural changes induced by clomiphene on intracellular L. mexicana amastigotes. Electron transmission microscopy micrographs with red scale bars correspond to low magnification images to show the general structure of infected macrophages. Micrographs indicated by black scale bars, correspond to magnifications of framed zones. N, macrophage nucleus; n, amastigote nucleus; PV: parasitophorous vacuole; FP, flagellar pocket; *, intracellular parasites within parasitophorous vacuoles; red circles, enlarged parasitophorous vacuoles; red stars, destroyed parasites within the parasitophorous vacuole. Black scale bars = 2 µm; red scale bars= 1 µm.

Figure 5.

Structural changes induced by clomiphene on intracellular L. mexicana amastigotes. Electron transmission microscopy micrographs with red scale bars correspond to low magnification images to show the general structure of infected macrophages. Micrographs indicated by black scale bars, correspond to magnifications of framed zones. N, macrophage nucleus; n, amastigote nucleus; PV: parasitophorous vacuole; FP, flagellar pocket; *, intracellular parasites within parasitophorous vacuoles; red circles, enlarged parasitophorous vacuoles; red stars, destroyed parasites within the parasitophorous vacuole. Black scale bars = 2 µm; red scale bars= 1 µm.

Figure 6.

Effect of clomiphene and tamoxifen treatment on lesion growth. *: p< 0.05, **: p< 0.01, ***: p< 0.001 (Compared to the control group).

Figure 6.

Effect of clomiphene and tamoxifen treatment on lesion growth. *: p< 0.05, **: p< 0.01, ***: p< 0.001 (Compared to the control group).

Figure 7.

Effect of treatment on lesion weight (a) and parasite load (b) one week after the end of treatment. *: p< 0.05, **: p< 0.01, ***: p< 0.001 (Compared to the control group).

Figure 7.

Effect of treatment on lesion weight (a) and parasite load (b) one week after the end of treatment. *: p< 0.05, **: p< 0.01, ***: p< 0.001 (Compared to the control group).

Table 1.

In vitro antileishmanial activity and cytotoxicity of clomiphene and tamoxifen.

Table 1.

In vitro antileishmanial activity and cytotoxicity of clomiphene and tamoxifen.

| Compound |

Promastigotes IC50 ± SD (µM) |

Cytotoxicity

CC50 ± SD (µM) |

Amastigotes

L. mexicana

IC50 ± SD (µM) |

S.I. |

| L. mexicana |

L. major |

L. amazonensis |

| Tamoxifen |

6.4 ± 2.1 |

2.9 ± 1.1 |

5.3 ± 0.5 |

18.8 ± 0.2 |

3.7 ± 0.3 |

5.1 |

| Clomiphene |

3.0 ± 0.6 |

1.7 ± 0.9 |

3.3 ± 0.8 |

19.8 ± 2.8 |

2.8 ± 0.2 |

7.1 |

| Amphotericin B |

0.039 ± 0.009 |

0.030 ± 0.002 |

0.028 ± 0.004 |

>6.7 (22.4)* |

0.29 ± 0.02 |

>23.1(77)** |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).