1. Introduction

Human contributions to environmental issues have become increasingly clear in the past decades. Almost 99% of climate experts agree that climate change is based on human activity [

1]. Reports about deforestation [

2], mass extinctions and biodiversity loss [

3], and emergencies like floods and droughts [

4] clearly highlight the human impact on those outcomes. Individual behavior change in the domain of pro-environmental behavior (PEB), that is, the adoption of behaviors that provide relative benefits for the natural environment [

5,

6], may help to mitigate these issues.

People may engage in a specific PEB for a variety of different reasons. For example, an individual may use the bicycle (instead of the car) to go to work to protect the environment or to obtain health benefits or social approval [

7]. Irrespective of the kind of motivation, barriers may keep people from engaging in PEBs. Understanding the nature of these barriers might shed more light on how to successfully implement PEB change [

8,

9,

10]. Barriers play a key role in the framework proposed by Kollmuss and Agyeman (2002), one of the most seminal works in PEB research [

11]. Kollmuss and Agyeman distinguish between external and internal barriers. External barriers include economic factors (i.e., market and organizational disincentives for PEB), institutional factors (i.e., lack of structural support and system-provided information on how to perform PEBs), and socio-cultural factors (i.e., social norms favoring environmentally harmful behaviors) [

9]. For example, a person may refrain from behaving pro-environmentally in a particular domain if the environment does not provide any options to do so, if these options are hard to identify, or if choosing these options is very costly. Internal barriers include a possible lack of awareness of sustainable solutions, emotional and cognitive engagement in competing actions, competing values, and an external locus of control (i.e., an actors' perceived inability to produce change through their actions) [

9]. These internal barriers interact with one another, contributing to the intricate nature of behavioral change [

12].

Internal barriers are also central to the work of Gifford and colleagues on so-called dragons of inaction in the PEB domain [

8,

13]. Initially, Gifford has proposed a set of 30 barriers that may prevent PEB change (e. g., comparison with others, sunk costs, perceived risk, limited cognitions, ideologies, disbelief, limited behavior) [

8]. Based on psychometric analyses, these barriers have been grouped into 5 higher-order categories: change unnecessary, conflicting goals and aspirations, interpersonal relations, lacking knowledge, and tokenism [

13]. For example, people may not engage in a particular PEB because they deny the seriousness of environmental issues (change unnecessary) or because they hold goals which are incompatible with engagement in that behavior (e.g., they want to be at work as fast as possible and thus choose the car instead of the bicycle; conflicting goals and aspirations). They may be afraid of being judged by others (e.g., when arriving at the office in sweaty clothes; interpersonal relations) or unaware of how to implement the behavior (e.g., about how to reach a destination by bicycle; lack of knowledge). Finally, they may reason that they already do enough to mitigate environmental issues (e.g., turn off the lights when leaving a room), so they do not need to engage in additional PEBs (e.g., cycling to work; tokenism).

The barriers discussed above were identified through the theoretical reasoning of experts in the field of PEB research and reviews of the existing PEB literature [

8]. This literature, however, is largely dominated by quantitative research designs [

14], which may exclude the views and works of “

scholars who do not fit the normative view of who a scientist is” [

15] (p.1). Due to the less restrictive and more exploratory nature of qualitative methods (e.g., interviews, focus groups, ethnographic approach, and participant observation), they may allow identifying barriers that are not included in established (and quantitatively tested) barrier frameworks [

13]. They may also be particularly suited to gain a first understanding of complex issues [

16], such as the interaction between different types of barriers. Despite these potential advantages, only a few PEB studies have used qualitative methods [

14] and the available insights have not been systematically integrated. The present review provides a first synthesis of the qualitative literature on barriers to PEB By this means, we aim to examine if the results of qualitative PEB studies converge with established barrier frameworks [

8,

9,

13].

2. Methods

We conducted a rapid evidence review of the qualitative academic literature on barriers to PEB change. Inclusion criteria were developed based on a first scoping search. The exclusion and inclusion criteria were developed in line with the research questions, using the standard PICOS format (population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study context) (Appendix A.1) [

17,

18,

19]. To be included in our review, academic papers (published journal articles or preprints) had to 1) examine one or more human behaviors of relevance for the natural environment (i.e., a domain of potential PEB), 2) focus on one or more potential barriers to engagement in these behaviors, 3) use a qualitative research design (i.e., interviews, focus groups, ethnographic observation). Publication period was limited to after 2012 to ensure timely results and to balance efficiency and comprehensiveness of the review. Articles had to be written in English and to report data from human respondents not younger than 12 years.

Our literature search was conducted at the Web of Science in August 2022. The PEB-related part of the search string was adopted from related reviews of the PEB literature [

10,

20,

21] and we added search terms to ensure the fit to the scope of our review:

TS=("environment*behav*" OR "proenvironment* behav*"" OR " recycling behav*" OR "conservation behav*" OR "ecological behav*" OR "environmentally relevant behav*" OR "environmentally responsible behav*" OR "ecologically relevant behav*" OR "ecologically responsible behav*" OR "environmentally friendly behav*" OR "environmentally significant behav*" OR "environmentally supportive behav*" OR "climate friendly behav*" OR "sustainable behav*" OR "green behav*" OR "environmental action*)

NOT TS=("major clinical study" OR "controlled clinical trial")

AND TS=("barrier")

AND TS=("interview" OR "focus groups" OR "ethnography observations" )

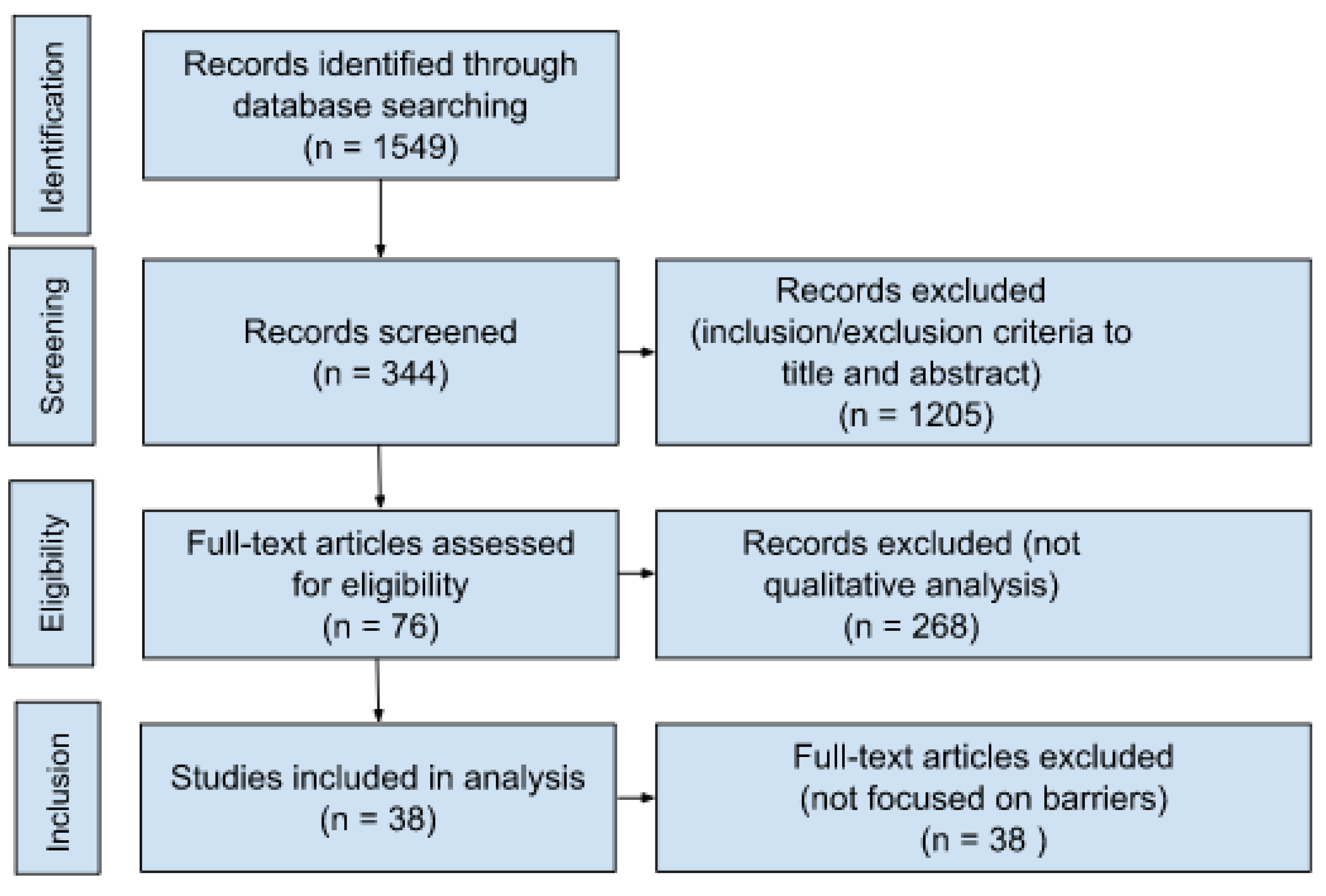

This search returned 1549 results. Articles were then assessed by the first author for relevance according to the study title and abstract. The first sift applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to the title and abstract, with a full paper analysis for the second sift. During these initial stages of sifting, she focused on ascertaining that the studies in question report data from qualitative research methods. In the final selection phase, she excluded qualitative studies that were not related to barriers of PEB change. This yielded a final sample of 38 included articles. A flow chart of the search process can be seen in

Figure 1.

3. Results

An overview of the characteristics and research questions of the 38 identified qualitative studies can be found in

Table 1. Most of these studies used (semi-) structured interviews (29). Additionally, focus groups (10) and ethnographic approaches (3) were used. The combined number of methods exceeds 38 because some studies employed multiple methods (

Table 1).

Studies differed in the scope of their PEB-related research focus. Some studies examined the barriers of adopting green lifestyles or reducing carbon emissions in general (28.9%) while others focused more specifically on green consumption choices (15.8%). Other specific PEB domains included green transportation (13.2%), energy saving (10.5%), meat consumption reduction (7.9%), recycling (5.3%), and saving water (2.6%). Yet other studies did not focus on specific PEBs, but on PEBs in specific settings, that is, in the workplace (10.5%) or while traveling (i.e., sustainable tourism, 5.3%).

Of note, the first thing that our review revealed was that studies focused on the barriers of PEB of different types of actors operating at different levels. Although most articles (k = 26, 68%) studied the factors individuals cite as barriers to their pro-environmental engagement, a substantial set of studies did not focus on individual citizen’s barriers. Some studies (k= 4, 11%) looked at barriers at the community level, for example, by interviewing actors within local authorities about the barriers they experience when implementing pro-environmental policies. Yet other studies (k = 8, 21%) focused on barriers that may keep actors on the industry level from reducing the ecological footprint of business activities. In the following, we will provide an overview of the barriers identified at these different levels, starting with the external barriers before progressing to the internal barriers. We will examine whether the barriers mentioned in influential PEB frameworks [

8,

9,

13] can also be found in the qualitative literature.

3.1. External Barriers

3.1.1. Economic Barriers

According to Kollmuss and Agyeman (2010), economic factors play a significant role as barriers to pro-environmental behavior [

9]. The cost of pro-environmental alternatives may discourage individuals from engaging in environmentally friendly actions. Economic barriers encompass various aspects such as high financial costs of pro-environmental solutions [

33] and lack of investment money for environmentally friendly technologies [

32,

54].

At the individual level, economic barriers were repeatedly discussed. For example, participants in the study by Johnstone and Tan (2015) voiced concerns about the financial challenges associated with pro-environmental consumption choices: “

Well if you’re struggling to pay the bills, you’re not going to worry about it [buying green products]” [

54] (p.317)

; “Alternative products are quite expensive. My children have grown up…But there was a time where I had four little children…I couldn’t afford those things. We were saving for a house” [

54] (p. 317). Concerns about financial costs were also evident in discussions related to septic system maintenance. Malfunctioning, improperly sited, or poorly designed septic systems pose a contamination risk to drinking water sources, thereby endangering environmental and human health [

33]. Participants of the study by Devitt et al. (2016) expressed worries about the expenses associated with de-sludging and potential costs resulting from system inspection failures:

cost to have them [septic system]

de-sludged every year; it is a burden” [33, p.541]; “…

if I was to put a cost on it, it would have been €1,000 to get the work and whole lot done… that’s an expense that I just can’t bear at the moment” [

33] (p.541). The experts from the economic and business sectors in the study by Tröger and Reese (2021), for instance, struggle with the question of how to establish individual-level pro-environmental practices within a competition-based and consumption growth-oriented market environment: ”

In my opinion, it would be a cultural revolution. I think it would mean another log-ic within our society. […]

These growth-oriented lifestyles that are based on the idea of more, faster, higher, need to be changed completely” [

29] (p.831).

From the community level perspective economic barriers were also mentioned. Among them are economic norms and regulations, that is, the dominant economic model of growth orientation [

22], and general economic conditions, which include both market and organizational incentives and disincentives [

22]. Revell (2013) noted, based on semi-structured interviews with local authorities, that it is not enough for a local pro-environmental project to demonstrate impact on the reduction of carbon emissions to get approval from local municipalities [

22]. Instead, they seem to require the demonstration of direct financial savings for the city council:”

As a result, projects that could deliver carbon savings but fail to represent a cost-benefit generally do not obtain approval for delivery. However, when such projects do go ahead, officers observed that they do deliver significant carbon savings” [

22] (p.209).

Economic barriers were repeatedly mentioned at the industrial level. These barriers include the high cost of environmentally preferable technology [

35,

44,

48], lack of funding [

24,

44], and low consumer demand for environmentally friendly products [

12]. In a study by Williams and Schaefer (2012), cost factors were frequently cited as a barrier to pursuing PEB (e.g., energy saving) by managers of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in the East of England [

44]. Based on interview results, Long et al. (2016) highlighted that many potential users of pro-environmental agricultural technological innovations found them to be prohibitively expensive, primarily due to high upfront costs and lengthy return on investment periods. “

Major difficulties are due to the cost of investment, which is not enough balanced by the increase of yield nor the price of agricultural products.” [

48] (p.17). “

Many technologies have long payoff times and do not fulfil internal payoff criteria” [

48] (p.17). In their 2021 study, Hübel and Schaltegger observed that while there is high global demand for conventional meat products, pro-environmentally produced meat remains confined to market niches due to consistently low consumer demand and the absence of a globalized market for such products. Consequently, this situation discourages meat industry actors from pro-environmental products as viable alternatives [

12]. Based on semi-structured interviews, Bruce and Spinardi (2018) emphasized that the airliner development industry is risk-averse when it comes to adopting PEB [

38]. This caution is primarily for commercial reasons and is further reinforced by the distinct safety culture of civil aviation. As a former Boeing engineer stated: “…

there is an initial cost to design or ‘draw’ a new airliner that ‘you cannot overcome because of all of the data requirements to certify an aircraft’ so that ‘once you draw this aeroplane you’ve incurred this cost, and … you’re locked in.” [

38] (p.39).

3.1.2. Institutional Barriers

Institutional barriers are systemic barriers that make or keep PEBs relatively more costly or less beneficial than their competing alternatives [

59]. For example, lack of organizational and governmental action to structurally support PEB (e.g. infrastructure to bike) is considered a barrier to individuals’ engagement in PEBs that depend on such systemic structures (e.g. commuting by bike) [

13,

59].

These barriers were repeatedly mentioned at the individual level, including physical, structural, and infrastructural conditions as barriers [

32,

41,

49,

53,

57]. For instance, in Biggar and Ardoin's (2017) study, physical conditions played a significant role in shaping personal transportation behaviour. For example, one study participant considered biking or taking the bus to work as unlikely options: “

Bicycl[ing]

is about 45 minutes and arriving a bit winded and sweaty [or] 45 minutes in a bus where you are probably a little antsy about getting things done … I already get up at 5:30/6:00 and I would have to get up almost an hour earlier [to bike or take the bus]

. I don’t think that is really worth it” [

57] (p.146). Focus-group participants in a Norwegian study also discussed several structural barriers to PEB, such as cold climates and limited winter daylight affecting heating demands [

32]. Family size and composition, building characteristics (age, size, type, ownership), job demands, and technical issues (e.g., energy-saving lightbulbs, cycle lane quality, public transport connections) were also discussed. For example, having children or elderly family members is perceived as a barrier to energy improvements, as these groups are thought to require higher room temperatures and more frequent washing [

32]. Bly (2015), drawing from the results of semi-structured interviews, finds that the fashion system simply cannot be reconciled with pro-environmental product offerings [

53]. Participants argued that the systemic problem stems from the incessant pursuit of profit, driving the search for low-cost labour and cheaper materials, and escalating resource utilization to meet expanding sales requirements [

53]. Required infrastructure not being available also has been mentioned as a barrier, for example:”

Hotels don’t have recycling facilities” [

49] (p. 89).

Institutional barriers were repeatedly mentioned in qualitative studies from the community level perspective. These barriers include infrastructural barriers such as the lack of governmental assistance [

22] and lack of political support [

28]. Wang's (2018) study highlighted a historically determined lack of space as one of the main barriers experienced by urban planners aiming to improve cycling infrastructure in the city of Hamburg. “

So all the area as it is now—the split up between pedestrian, parking cars and bicycle—[are] from 1970s and 1980s, that means the time when Hamburg has the main goal to be a car-friendly city” [

28] (p.7). Given the existing, car-friendly design of the city (including street trees and on-streetcar parking), the interviewed urban planners reported difficulties broadening cycling lanes and adding cycle parking facilities. They and an interviewed local pro-cycling transportation researcher also discussed adverse effects resulting from the lack of political support, noting that the overarching local transport policies in Hamburg continue to prioritize motor traffic [

28].

Institutional barriers were repeatedly mentioned at the industrial level perspective too. The adoption and implementation of PEB can be influenced by various factors related to lack of organizational, governmental, and structural support [

12,

24,

38]. In their study, Hübel and Schaltegger (2022) found that any transformation toward sustainability in the meat industry requires changing interactions in the supply chain and cannot be realized by a single actor [

12]. Instead, multiple actors must agree on similar changes and act in a coordinated manner. One meat company manager outlined the challenges associated with introducing organic meat products: “

We as [Meat company]

have not even access to the farmers. This means that I always have to contact the slaughterhouse first to get in contact with the farmers. And then, the slaughterhouse and [Meat company]

have to convince the farmer: we'd like to do it like this, would you join? But the farmer will only join if he gets more money.” [

12] (p.135). In the study by Scarborough and Cantarello (2018), interviewed university sustainability projects assistant emphasized that a lack of organisational support at the university level creates diverse challenges in promoting staff engagement with pro environmental initiatives. These challenges range from resource allocation issues to the university's top-down management structure, each demanding unique solutions [

24].

3.1.3. Socio-Cultural Barriers

Socio-cultural factors can significantly influence people's behaviour towards environmental issues [

9]. Engaging in PEBs may be perceived as socially unacceptable or unexpected within their societal context [

9,

60]. For example, cultural variations in whether individuals prioritize personal goals over group objectives can significantly influence the behaviours they choose to engage in and their levels of commitment to PEB [

9].

On the individual level, several articles reported this barrier. The first issue that caught our attention was that it was reported that some people feared being perceived to “

sound preachy” [

25] (p.404) and that their (less pro-environmental) flatmates might think that they are weird for caring about small things like turning off their lights and only filling the kettle halfway [

54]. This fear emerged as a barrier in targeted interviews [

25] and focus groups [

54]. A second main topic that was mentioned in the studies was related to the workplace. It was mostly stated that people felt pressured to perform their work duties [

31] or felt like they were not important enough to implement changes [

23,

31]. This problem was pointed out by Smith and O’Sullivan (2012), where a focus group of individuals at the workplace uncovered that even though they considered it obsolete to print 1000 pages

“[…] they’ll just get told, we need it, do it” [

31] (p.483). The importance of social hierarchy is in line with what one individual stated in a semi-structured interview “

The [environmental] projects should be proposed by relevant members of the firm or organization” [

23] (p.836). It also highlights that taking any kind of pro-environmental initiative might not be perceived well by their colleagues and superiors. In addition, in Brazil, there are social expectations of taking part in barbeques that include the making and consumption of meat. Participants in the focus group highlighted that not taking part in this tradition might marginalize them in their peer group. This can also be seen in one of the problems of promoting PEB that was identified by interviewees in interviews with Hafenscher and Janko (2022), where social inertia (hence the resistance to change of a social group) hinders personal change and action even if the message on how to behave more pro-environmentally was successfully delivered [

27]. Therefore, the persistence of the social norm (consuming meat) and the fear of losing a social group is a significant barrier to changing to a more sustainable diet.

On the community level, we identified social and cultural norm barriers that act as barriers against the efforts of local authorities. Wang (2018) discusses that policies that are suggested/implemented by local authorities are not accepted by the public [

28]. Namely, it is stated that “

They [Shop owners] are afraid if we take the car parking space away and put places for bike, they think they would get bankrupt, nobody will buy anything from them.” [

28] (p.10) and that some ““[…]

cyclists are also motorists and they say ‘no, I wouldn’t want to give up my parking space’” [

28] (p.10). Therefore, violating the cultural norms of the citizens can be a barrier to policymakers as it influences the acceptability of the policy measures.

For the industry level, we were able to identify one article that revealed socio-cultural barriers. Hübel and Schaltegger (2022) asked several industry actors about barriers to adopting sustainable meat production practices. In the interviews, it was highlighted that many industry actors are growing frustrated about the ‘

unfair’ treatment by the media […]

and the lack of appreciation from the public for their (sustainability) efforts” [

12] (p.134). Therefore, continuing these practices or even adapting new ones might be hindered by the perception of the unaccepting society around the industry actors.

Across individual, community, and industrial levels, reoccurring barriers to adopting PEB are rooted in economic, socio-cultural, and institutional challenges. Individuals often face financial constraints and physical limitations; communities grapple with existing economic models and lack of political support, while industries confront high costs of sustainable innovations and coordination challenges among stakeholders.

3.2. Internal Barriers

For our review of internal barriers, we focused on the five higher-order barrier categories suggested by Lacroix et al. [

13] as the latest and most parsimonious version of the established dragons of inaction framework [

8]. We examined whether barriers from these categories have also been revealed by qualitative research. To do that, we again investigate three different levels: the individual, community, and industry level. Some factors that we have discussed as external barriers above may reappear here if they can also be construed as an internal barrier (see Discussion).

3.2.1. Change Unnecessary

Change unnecessary refers to the phenomenon that some people do not think that they can do anything about climate change, which relates to topics of climate change denial and shifting the blame to bigger institutions and therefore highlighting that own behavior change would only have a very limited effect on the environment.

At the individual perspective, change unnecessary was repeatedly mentioned. Key points are the perceptions of relevance and personal impact, as individuals may not perceive sustainability as relevant to their own lives or prioritize it accordingly [

26,

45,

47]. Individuals seem to have a difficult time changing their lifestyle if the problem is perceived to be in the distant future. For example, one educated adult stated: “

We will eradicate it [climate change] if we are affected by it in our vicinity” [

26] (p.35). This indicates that some individuals do not perceive climate change to be of immediate danger and any changes can be postponed until the effects are felt. Further, while a majority of the people interviewed by Graham-Rowe et al. (2014) reported being concerned about reducing food waste, other people simply did not see the need to change their behavior as they felt like food waste was inevitable [

45].

One barrier that was reported on the community level was the lack of governmental support in the community decision-making process. A local United Kingdom authority reports, for instance that “

if you have someone up there [...] who doesn’t believe, who is a climate sceptic then nothing will go ahead, it’s like a barrier, a wall, that’s it" [

22] (pp. 208-209). In this case, a higher up local authority council actor does not believe that there is a problem of climate change and therefore will not do anything to counteract it.

From the industrial level perspective, one notable barrier that arises is the perceived expectations from the end-users [

39]. Sustainability experts and practitioners in a focus group discussed why the Australian building industry does not commit to sustainable changes. This paper suggests that actors in the building sector see a lack of sustainability motivation in society as a significant barrier keeping them from moving along with sustainable technology. Hence, big changes need to wait until the community pressures the government for more sustainable standards within the building industry. Until then the industry is not interested in promoting more sustainable protocols and intends to continue the current system with limited improvements over time. That is, they do not see the necessity for significant changes in the absence of societal pressure as "Market and government will not put money into that area of the market because it's a cash cow for them, they are making too much money out of people using a lot of electricity” [

39] (p.289). This implies that change is deemed as unnecessary until other actors are advocating for the changes.

3.2.2. Conflicting Goals and Aspirations

The second internal barrier category deals with conflicting goals and aspirations. This means that people are not engaging in PEB because other goals are keeping them from acting pro-environmentally.

On the individual level, pro-environmental behaviour was often associated with effort and losing comfort. One focus group participant stated, for example, that “…

we are dependent on money and facilities. We are becoming individualistic, we want own AC, own TV.” [

26] (p.40). Similarly, in a focus group by Johnstone and Tan (2015), one consumer who expressed that they were concerned about the environment stated “

I think at the end of the day people are inherently lazy. And if it’s too hard they’re not going to do it” [

54] (p.316). According to this participant, the goal of protecting the environment requires effort and time and therefore might compete with the goal of having a relaxed life. Another facet of conflicting goals was related to food waste [

45,

50]. Semi-structured interviews with people who generally are the household food purchasers conducted by Graham-Rowe et al. (2014) highlighted that consumers generally cared about not wasting food [

45]. However, the goal to conform to their roles was perceived as a hindrance to following through on reducing food waste. It was stated that being a good parent, spouse, or host was often perceived as more important than not wasting food. Therefore, purchasing a lot of (healthy) food was seen as important, even if it went to waste due to over-purchasing. Convenience and comfort, again, played a role in wasting food: It was stated that stockpiling food gave peace of mind when thinking of uncertainties of the week ahead and helped plan for unexpected events. This comes at the clear cost of more food going to waste [

45].

Secondly, conflicting goals and aspirations are also found on the community level. A cycling planner (from the Ministry of Economy, Transport, and Innovation) in Hamburg stated that there is a conflict between the goals of private car owners who want to continue benefitting from parking spots in front of their houses and the building of bike paths. For example, they state that “

They [the citizens]

want to influence the road. […] Whether the tree in front of their house they want to keep, or whether there are parking spaces which they believed to be their own parking space in front of their house, and so on, so this is very complex.” [

28] (p.9). Other community members are worried that reducing car parking spaces would harm their business and “

some cyclists are also motorists, and they say ‘no, I wouldn’t want to give up my parking space’” [

28] (p.10). To navigate these conflicting goals, community decision-makers often need to engage in time-consuming negotiations with all stakeholders involved.

The industry level describes the issue of many changes being time-intensive and that, therefore, some priorities have to be made to manage the work [

24,

38]. Bruce and Spinardi (2018) found that farmers taking part in the semi-structured interviews state that they often do not have time to switch to new, more sustainable technologies and practices even though several farmers stated that they are not in principle against switching to a more sustainable farming strategy [

38]. Another interesting conflict experienced by farmers emerged between the goal to produce in an environmentally friendly way and the goal to adopt animal welfare-enhancing practices, such as raising slow-growing animal breeds, which the farmers also experienced to be important to consumers. Raising animals to be slaughtered at a later age relates to health and welfare benefits, but also consumes more resources [

38].

3.2.3. Interpersonal Relations

Individuals, community decision-makers, and business decision-makers may refrain from adopting pro-environmental practices because they fear that other people might disapprove of them behaving pro-environmentally. In this sense, interpersonal relations can also be seen as a socio-cultural factor, that is, as the social or cultural norms an actor is afraid to violate through behaving pro-environmentally (see section 3.1.). In addition to the barriers mentioned within the social and cultural norms, lack of trust has been a reoccurring barrier in the qualitative studies we reviewed. This is seen in not trusting the government and not trusting the community (free riders), lack of trust in social media, and distrust of expert knowledge claims [

22,

34,

41,

46,

51,

53].

At the individual level, issues related to trust and credibility were raised by Carrete et al. (2016) [

51]. Some interviewees indicated that they do not buy products that are better for the environment because they do not trust the advertisement claims regarding the environmental performance of those products.: “

We don't know if we should trust [them] […]. On TV, even cookies talk! So you should not believe everything they say “[

51] (p.476). For instance, families argue that they don't segregate waste since the local administration doesn't provide distinct waste collection services: “

When the garbage truck comes, the operators mix everything – there's no point in it “[

51] (p.476). In their focus group study, Happer and Wellesley (2019) found that key barriers in promoting dietary shifts towards a more pro-environmental model include a lack of trust and credibility regarding scientists and government among UK and US samples. Climate change was broadly perceived as a politically contentious issue within these groups. Participants believe that politicians were not prioritizing the public's best interest: “

I think that all politicians have a, ah, set agenda. So, I mean, whoever is really backing them I think they are going to take their side on any subject. So – “[

34] (p. 133).

At the community level perspective, these barriers were repeatedly mentioned, including factors such as lack of trust in government and news resources [

22]. Revell (2013) studied local authorities working to address unsustainability and promote pro-environmental behaviour among their populations. However, these authorities often faced challenges in engaging residents because they distrusted such entities: “…

because it is a local authority and some people just don't want to engage with local authority, don't trust them “. [

22] (p. 210). In Viardot's (2013) semi-structured interviews study on how cooperatives can influence the behaviour of their members so that they switch from the use of traditional fossil energy to renewable energy, free riding behaviour was highlighted as a significant barrier [

46]. It was associated with the belief that a programme will be implemented within the cooperative with or without one’s support, thus providing one with all the public benefits without any personal cost [

46].

From the industrial perspective, lack of trust in external expertise [

38] was mentioned. Bruce and Spinardi (2018) found in their study that distrust of expertise significantly limits the uptake of estimated breeding values, which offer yearly incremental improvements in efficiency and consequent reductions in greenhouse gases emissions [

38]. Many farmers exhibited distrust towards scientific expertise due to its perceived past failures, such as handling animal disease outbreaks, and an apparent lack of understanding of the practical challenges faced by farmers. One farmer commented: “

Agriculture has always been pretty quick to take on board new things that were deemed to be good, but we’ve had quite a lot of stuff come at us that’s … turned out to be bad. “[38, p.41].

3.2.4. Lacking Knowledge

The fourth barrier is lacking knowledge of how to act more pro-environmentally, that is, people, community decision-makers, and industries are simply unaware of changes that can be implemented.

On the individual level, a first problem that was identified using structured interviews is that people sometimes struggle with concepts that do have not one overarching definition. One such example reported by Uren and colleagues (2017) is sustainability, which some participants interpreted as living within their limits and others as “

protecting their lifestyles” [

25] (p. 402). When participants were asked about recycling, it was reported that recycling is often seen as something good without questioning the consumption part that is connected to it [

25]. One participant stated, “

I think as a society even within the sustainability realm it is really hard to understand what that actually means because something that is recycled is assumed automatically to be sustainable” [

25] (p.401). There, participants criticized that people do not know that consuming has a negative impact on the environment and that some people think that recycling is an effort toward sustainability. In line with this, it was reported that people generally did not understand that food waste harms the environment. One participant interviewed by Graham-Rowe et al. (2015) stated that food waste is not bad because “

food rots down, doesn’t it?” [

45] (p.19). Lastly, Devitt and colleagues (2016) reported that necessary technical knowledge on how to maintain septic water systems or what is allowed to enter a septic water system was largely unknown to the users [

33].

Secondly, the lacking knowledge barrier is also portrayed at the community-level perspective. Interviews uncovered the main barriers, which included the lack of valuable information that could be used to assess whether the local authorities' sustainability projects were successful [

22]. This acts as a barrier for the local authorities as more effective projects cannot be created based on the lack of knowledge of the effectiveness of the initial projects.

Lacking knowledge was identified as a barrier in several of the considered articles for the industrial level. Here, these barriers include the failure to understand the extent of the problem. For instance, qualitative interviews have revealed that many beef and sheep farmers did not perceive methane as a pollutant, but rather considered it as a natural and inevitable component of livestock agriculture and even believe that what they are doing is environmentally beneficial as “

my sheep… they don’t get fed anything that makes them more gaseous, they’re just eating what’s naturally here" [

38] (p.41). This lack of information therefore could be a reason that keeps them from switching to more pro-environmental farming methods and attempting to reduce the demand. Additionally, barriers at the industrial level may involve issues related to blocking relevant knowledge which impedes change in livestock farmers and butchers [

12]. Specifically, their emotional commitment to their industry and to make “

top quality” [

12] (p.134) meat is associated with specialized knowledge in meat production and rejecting plant-based meat alternatives. Therefore, the existing structures are not questioned by these farmers and additional information is rejected. Martek et al. (2019) also stressed that the lack of knowledge and awareness of the end user is inhibiting implementation of more sustainable housing infrastructure options [

39].

3.2.5. Tokenism

The last psychological barrier discussed in Lacroix et al. (2019) is the barrier of tokenism [

13]. Tokenism is the expectation that one is already doing enough to counteract the negative effects of climate change and therefore no more effort must be invested.

On the individual level, one prominent barrier is the tendency for individuals to focus on making small changes within their household rather than engaging in broader activism [

25]. This "

doing my bit" [

25] (p.404) mentality often limits the scope of their environmental efforts and keeps people from taking part in more large-scale environmental actions. Along similar lines, some respondents interviewed by Miller et al. (2014) indicated that they are taking a break from environmental responsibilities while on vacation where they, for example, recycle less than when they are at home [

42].

An example of tokenism on the community level is given by a city council’s lack of dedication to sustainability policies. A local authority sustainability officer reports, for instance, that “

the council wants to be seen to be doing something but doesn't really want to have to worry about sustainability too much" [

22] (p.209). This implies that the councils are interested in symbolically partaking in environmental actions but are not interested in doing something meaningful. Consequently, the lack of support by the council prevents the sustainability officers from effectively carrying out pro-environmental projects.

Lastly, on the industrial level Hübel et al. (2022) noted that some of the interviewed meat industry actors believe they continue making efforts towards sustainability. Some farmers expressed concerns, stating that they “

don’t know how long they will still have the strength to continue making efforts that nobody appreciates” [

12] (p.134). This quote shows that actors within the meat industry perceive a lack of appreciation for their sustainability efforts. Further, they criticize a perceived injustice towards other areas of production and consumption that are not challenged as much. This may mean that partaking more in sustainability actions is not an option, as there seems to be a depletion of strength. This illustrates how the lack of appreciation and accountability for other industry actors can be construed as a barrier to additional pro-environmental efforts [

12].

4. Discussion, Conclusions and Future Directions

Our review of recent qualitative studies sheds new light on the barriers that keep people from engaging in pro-environmental behaviors in multiple ways. First, we found that the barriers that are being identified and discussed in qualitative explorations can be organized along the lines of established barrier frameworks [

8,

9,

13]. Each of the barriers we encountered can be categorized according to these frameworks and none of the barriers specified in these frameworks failed to appear in the qualitative work we reviewed. This finding supports the exhaustiveness and utility of prior frameworks for the organization of PEB barriers. Nevertheless, several findings proved hard to classify unequivocally. Often, internal barriers and external barriers are two sides of one coin. When a commuter indicates not to cycle because it entails travel times of “

about 45 minutes and arriving a bit winded and sweaty” [

57] (p.146), we classified it as institutional barriers, but one could also argue that this person’s competing goal to arrive at work fresh conflicts with the goal to commute by bike. Adequate classification of the barriers may have an important impact on the effectiveness of interventions that are designed to address these barriers. We suspect that such problems risk to remain under the surface in the context of quantitative research because the classification is done upfront.

Second, the barriers discussed in the qualitative literature do not only pertain to the pro-environmental actions of individuals in their role as citizen or consumer. Several of the studies we reviewed focused on the barriers that keep community-level actors from implementing pro-environmental policies or industrial decision-makers from taking pro-environmental business actions. This indicates that the barrier concept can also be applied to actors and levels different from the individual. Potentially, research on the behavior of community and industry-level actors can benefit from adopting insights generated by individual-level research guided by the barrier concept [

15]. However, explaining a lack of pro-environmental action in terms of barriers may also be harmful, especially if the barriers are conceptualized as intrinsic and non-changeable properties of actors, groups, or societies [

62]. For example, attributing a lack of pro-environmental engagement to social inertia may contribute to the narrative that social customs cannot be changed.

Third, the studies we reviewed illustrate that qualitative studies can provide information on the barriers of pro-environmental behavior that are very difficult to generate using quantitative methodology. For example, Wang [

28] reported that a cycling planner stated that citizens want to have their say in the trees, parking spaces, and cycling lanes in front of their doors. This reveals the complexity of such situations that goes much beyond ‘acceptance’ of cycling lanes or trees in city centers per se. These insights inform our understanding of the factors that keep actors from engaging in the respective behaviors and they point to new possible approaches for changing the behaviors in question. It is difficult to imagine how such information could have been generated by a quantitative survey.

Limitations of our rapid review include reliance on a single database and incorporating relatively few studies. The low number of included studies is partially due to a scarcity of qualitative research on explicit barriers to PEB and we therefore support recent calls that invite more qualitative research methods into PEB research [

15,

63].

Overall, this rapid review identified 38 qualitative studies that explored barriers preventing agents from engaging in PEBs. These studies investigated a broad array of barriers, considering perspectives at three distinct levels. Our findings highlight the multifaceted nature of barriers to PEB change and underscore the significance of addressing structural and institutional factors alongside individual-level interventions. In revealing perspectives of actors on the community and industry level, our review also underscores the relevance and the potential complementarity of qualitative research in the PEB domain. We hope that our analysis of barriers across levels may inspire future research to consider the complexity of barriers and ultimately result in more effective interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Albina Dioba, Siegfried Dewitte, Valentina Kroker and Florian Lange; methodology, Albina Dioba; validation, Albina Dioba and Valentina Kroker; formal analysis, Albina Dioba and Valentina Kroker; investigation, Albina Dioba; resources, Siegfried Dewitte; data curation, Albina Dioba; writing—original draft preparation, Albina Dioba, Valentina Kroker, Florian Lange and Siegfried Dewitte; writing—review and editing, Albina Dioba, Valentina Kroker, Florian Lange and Siegfried Dewitte; visualization, Albina Dioba; supervision, Albina Dioba and Siegfried Dewitte; funding acquisition, Siegfried Dewitte. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first author received funding from the SARU fellowship program, which is supported by the Carlsberg Foundation.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

PICOS framework.

Table A1.

PICOS framework.

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria: |

|---|

| |

Inclusion |

Exclusion |

| Population |

Human |

not human,

children under 12 years old |

| Intervention |

Barriers to

PEB change |

Medical interventions (i.e. health-related research).

Environmental structuring |

| Comparison |

Different barriers

and subsequent impacts |

|

| Outcomes |

Behavioural actions:

and:

Behavioral determinants:

psychological barriers, values,

attitudes, habits |

|

| Study design |

Qualitative |

Theoretical modelling

Review

Quantitative

Experimental

Quasi-experimental |

| Time |

Since 2012 |

Pre 2012 |

| Type of publication |

Academic publications

|

Anything else, i.e. media, blogs, theses.

Gray Literature (Gov. reports, NGO reports, third party consultant reports etc.) |

| |

|

if full text not available through KU Leuven Non-English language |

| Search strategy: |

| Electronic databases |

Electronic databases accessible at KU Leuven: Web of Science |

| Compiling |

Results will be compiled in Mendeley and search strings compiled in Excel |

| Review methods: |

| Reviewers |

only one researcher will conduct the review. Two rounds of sifting will enable greater rigor within this process. |

| Sifting |

First sift: application of inclusion/exclusion criteria to title and abstract.

Second sift: application of inclusion/exclusion criteria to full paper.

This will be recorded in PRISMA protocol |

| Data extraction |

Data from included studies will be extracted in Excel.

The data extraction framework will be developed iteratively based on key paper analysis, and will be focused on outcomes and study design |

Quality/risk of bias

assessment |

The quality assessment will be based on Rees et al.'s (2009) Quality Appraisal |

| Synthesis: |

Main synthesis areas:

1. Synthesise qualitative studies with rest of literature around barriers to PEB change. |

References

- Myers, K. F., Doran, P. T., Cook, J., Kotcher, J. E., & Myers, T. A. (2021). Consensus revisited: Quantifying scientific agreement on climate change and climate expertise among Earth scientists 10 years later. Environmental Research Letters, 16(10), 104030.

-

Land - the planet’s carbon sink | United Nations. (2022.). Retrieved May 2, 2024, from https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/climate-issues/land.

- Nations, U. (2022). Biodiversity - our strongest natural defense against climate change | United Nations. Retrieved May 2, 2024, from https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/climate-issues/biodiversity.

-

Vanessa Nakate: Climate change is about the people | United Nations. (2022). Retrieved May 2, 2024, from https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/vanessa-nakate-climate-change-is-about-people.

- Lange, F., & Dewitte, S. (2019). Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 63, 92–100. [CrossRef]

- Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2009). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(3), 309–317. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F. G., Kibbe, A., & Hentschke, L. (2021). Offsetting behavioral costs with personal attitudes: A slightly more complex view of the attitude-behavior relation. Personality and Individual Differences, 183, 111158.

- Gifford, R. (2011). The Dragons of Inaction: Psychological Barriers That Limit Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. American Psychologist, 66(4), 290–302. [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239–260. [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A., Boiral, O., Francoeur, V., & Paillé, P. (2018). Overcoming the barriers to pro-environmental behaviors in the workplace: A systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 379–394. [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M., Raza, A., Mansoor, A., Khan, M. S., & Lee, J. W. C. (2023). Trends and patterns in pro-environmental behaviour research: a bibliometric review and research agenda. Benchmarking, 30(3), 681–696. [CrossRef]

- Hübel, C., & Schaltegger, S. (2022). Barriers to a sustainability transformation of meat production practices - An industry actor perspective. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 29, 128–140. [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, K., Gifford, R., & Chen, A. (2019). Developing and validating the Dragons of Inaction Psychological Barriers (DIPB) scale. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 63, 9–18. [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K., Pearce, J., Dowling, R., & Goh, E. (2022). Pro-environmental behaviours in protected areas: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Tourism Management Perspectives, 41, 100943. [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, E., Ogunbode, C., Wilkie, S., Jones, C. R., Devine-Wright, P., Uzzell, D., Canter, D., Korpela, K., Pinto de Carvalho, L., & Staats, H. (2024). On the importance of qualitative research in environmental psychology. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 93. [CrossRef]

- Gear, C., Eppel, E., & Koziol-Mclain, J. (2018). Advancing Complexity Theory as a Qualitative Research Methodology. Https://Doi.Org/10.1177/1609406918782557, 17(1). [CrossRef]

- Graves, C., & Roelich, K. (2021). Psychological barriers to pro-environmental behaviour change: A review of meat consumption behaviours. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(21), 11582. [CrossRef]

- Collins, A., Coughlin, D., Miller, J., & Kirk, S. (2015). The production of quick scoping reviews and rapid evidence assessments: a how to guide. https://connect.innovateuk.org/documents/3058188/3918930/JWEG%20HtG%20Dec2015.

- Moons, P., Goossens, E., & Thompson, D. R. (2021). Rapid reviews: the pros and cons of an accelerated review process. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 20(5), 515-519.

- Yuriev, A., Dahmen, M., Paillé, P., Boiral, O., & Guillaumie, L. (2020). Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 155, 104660. [CrossRef]

- Lange, F., & Dewitte, S. (2019). Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 63, 92–100. [CrossRef]

- Revell, K. (2013). Promoting sustainability and pro-environmental behaviour through local government programmes: examples from London, UK. Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences, 10(3–4), 199–218. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Manzanal, R., Serra, L. M., Morales, M. J., Carrasquer, J., Rodríguez-Barreiro, L. M., del Valle, J., & Murillo, M. B. (2015). Environmental behaviours in initial professional development and their relationship with university education. Journal of Cleaner Production, 108, 830–840. [CrossRef]

- Scarborough, C., & Cantarello, E. (2018). Barriers to pro-environmental behaviours at Bournemouth University. Meliora: International Journal of Student Sustainability Research, 1(2). [CrossRef]

- Uren, H. v., Dzidic, P. L., Roberts, L. D., Leviston, Z., & Bishop, B. J. (2019). Green-Tinted Glasses: How Do Pro-Environmental Citizens Conceptualize Environmental Sustainability? Environmental Communication, 13(3), 395–411. [CrossRef]

- Garg, S. (2016). Climate Change Denial and Psychological Barriers to Pro-Environmental Behaviour. Journal of Innovation for Inclusive Development, 1(1), 33–42. http://archive.upub.in/jiid/2016/08/climate-change-denial-psychological-barriers-pro-environmental-behaviour/.

- Hafenscher, P., & Jankó, F. (2022). Environmental communication, from engagement to action: lessons from interviews with environmental experts, Hungary. Environmental Education Research, 28(12), 1777–1788. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. (2018). Barriers to Implementing Pro-Cycling Policies: A Case Study of Hamburg. Sustainability 2018, Vol. 10, Page 4196, 10(11), 4196. [CrossRef]

- Tröger, J., & Reese, G. (2021). Talkin’ bout a revolution: an expert interview study exploring barriers and keys to engender change towards societal sufficiency orientation. Sustainability Science, 16(3), 827–840. [CrossRef]

- Merkel, S. H., Person, A. M., Peppler, R. A., & Melcher, S. M. (2020). Climate Change Communication: Examining the Social and Cognitive Barriers to Productive Environmental Communication. Social Science Quarterly, 101(5), 2085–2100. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. M., & O’Sullivan, T. (2012). Environmentally responsible behaviour in the workplace: An internal social marketing approach. Journal of Marketing Management, 28(3–4), 469–493. [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C. A., Sopha, B. M., Matthies, E., & Bjørnstad, E. (2013). Energy efficiency in Norwegian households - Identifying motivators and barriers with a focus group approach. International Journal of Environment and Sustainable Development, 12(4), 396–415. [CrossRef]

- Devitt, C., O’Neill, E., & Waldron, R. (2016). Drivers and barriers among householders to managing domestic wastewater treatment systems in the Republic of Ireland; implications for risk prevention behaviour. Journal of Hydrology, 535, 534–546. [CrossRef]

- Happer, C., & Wellesley, L. (2019). Meat consumption, behaviour and the media environment: a focus group analysis across four countries. Food Security, 11(1), 123–139. [CrossRef]

- Bechini, L., Costamagna, C., Zavattaro, L., Grignani, C., Bijttebier, J., & Ruysschaert, G. (2020). Drivers and barriers to adopt best management practices. Survey among Italian dairy farmers. Journal of Cleaner Production, 245, 118825. [CrossRef]

- Jordová, R. , & Brůhová-Foltýnová, H. (2021). Rise of a New Sustainable Urban Mobility Planning Paradigm in Local Governance: Does the SUMP Make a Difference? Sustainability 2021, 13, 5950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerricks, S. , White, R. M., Lane, M., & Slevin, A. (2021). Communities on a Threshold: Climate Action and Wellbeing Potentialities in Scotland. Sustainability, 2021; 13, 7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, A., & Spinardi, G. (2018). On a wing and hot air: Eco-modernisation, epistemic lock-in, and the barriers to greening aviation and ruminant farming. Energy Research & Social Science, 40, 36–44. [CrossRef]

- Martek, I., Hosseini, M. R., Shrestha, A., Edwards, D. J., & Durdyev, S. (2019). Barriers inhibiting the transition to sustainability within the Australian construction industry: An investigation of technical and social interactions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 211, 281–292. [CrossRef]

- Torma, G. (2020). How to Cope with Perceived Tension towards Sustainable Consumption? Exploring Pro-Environmental Behavior Experts’ Coping Strategies. Sustainability 2020, Vol. 12, Page 8782, 12(21), 8782. [CrossRef]

- Tyers, R. (2021). Barriers to enduring pro-environmental behaviour change among Chinese students returning home from the UK: a social practice perspective. Environmental Sociology, 7(3), 254–265. [CrossRef]

- Miller, D., Merrilees, B., & Coghlan, A. (2015). Sustainable urban tourism: understanding and developing visitor pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(1), 26–46. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. N., Lobo, A., & Greenland, S. (2016). Pro-environmental purchase behaviour: The role of consumers’ biospheric values. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 33, 98–108. [CrossRef]

- Williams, S., & Schaefer, A. (2013). Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and Sustainability: Managers’ Values and Engagement with Environmental and Climate Change Issues. Business Strategy and the Environment, 22(3), 173–186. [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E., Jessop, D. C., & Sparks, P. (2014). Identifying motivations and barriers to minimising household food waste. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 84, 15–23. [CrossRef]

- Viardot, E. (2013). The role of cooperatives in overcoming the barriers to adoption of renewable energy. Energy Policy, 63, 756–764. [CrossRef]

- Winter, J., & Cotton, D. (2012). Making the hidden curriculum visible: sustainability literacy in higher education. Environmental Education Research, 18(6), 783–796. [CrossRef]

- Long, T. B., Blok, V., & Coninx, I. (2016). Barriers to the adoption and diffusion of technological innovations for climate-smart agriculture in Europe: evidence from the Netherlands, France, Switzerland and Italy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 9–21. [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E., & Dolnicar, S. (2014). The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 76–95. [CrossRef]

- Gullstrand Edbring, E., Lehner, M., & Mont, O. (2016). Exploring consumer attitudes to alternative models of consumption: motivations and barriers. Journal of Cleaner Production, 123, 5–15. [CrossRef]

- Carrete, L., Castaño, R., Felix, R., Centeno, E., & González, E. (2012). Green consumer behavior in an emerging economy: Confusion, credibility, and compatibility. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(7), 470–481. [CrossRef]

- Howell, R. A. (2013). It’s not (just) “the environment, stupid!” Values, motivations, and routes to engagement of people adopting lower-carbon lifestyles. Global Environmental Change, 23(1), 281–290. [CrossRef]

- Bly, S., Gwozdz, W., & Reisch, L. A. (2015). Exit from the high street: an exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(2), 125–135. [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, M. L., & Tan, L. P. (2015). Exploring the Gap Between Consumers’ Green Rhetoric and Purchasing Behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(2), 311–328. [CrossRef]

- Hoek, A. C., Pearson, D., James, S. W., Lawrence, M. A., & Friel, S. (2017). Shrinking the food-print: A qualitative study into consumer perceptions, experiences and attitudes towards healthy and environmentally friendly food behaviours. Appetite, 108, 117–131. [CrossRef]

- Gabler, C. B., Butler, T. D., & Adams, F. G. (2013). The environmental belief-behaviour gap: Exploring barriers to green consumerism. Journal of Customer Behaviour, 12(2), 159–176.

- Biggar, M., & Ardoin, N. M. (2017). More than good intentions: the role of conditions in personal transportation behaviour. Local Environment, 22(2), 141–155. [CrossRef]

- Elf, P., Gatersleben, B., & Christie, I. (2019). Facilitating positive spillover effects: New insights from a mixed-methods approach exploring factors enabling people to live more sustainable lifestyle. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(JAN), 417488. [CrossRef]

- Axon, S. (2017). “Keeping the ball rolling”: Addressing the enablers of, and barriers to, sustainable lifestyles. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 52, 11–25. [CrossRef]

- Chwialkowska, A., Bhatti, W. A., & Glowik, M. (2020). The influence of cultural values on pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 268, 122305.

- Ekdahl, M., Milios, L., & Dalhammar, C. (2024). Industrial policy for a circular industrial transition in Sweden: An exploratory analysis. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 47, 190–207. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M. T., Neufeld, S. D., Mackay, C. M., & Dys-Steenbergen, O. (2020). The perils of explaining climate inaction in terms of psychological barriers. Journal of Social Issues, 76(1), 123-135.

- Lloyd, S., & Gifford, R. (2024). Qualitative Research and the Future of Environmental Psychology. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 102347.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).