1. Introduction

Complicated acute bacterial rhinosinusitis is a condition that can result from the spread of a bacterial sinonasal infection to sinonasal contiguous districts and it is a relatively uncommon condition. [

3]

The most diffuse sinonasal infection is indeed the so called common-cold, a viral sinonasal infection that can evolve in acute post-viral rhinosinusitis (APVRS) which is characterized by worsening of nasal symptoms after 5 days or persistence of symptoms after 10 days, lasting less than 12 weeks in total: on the substrate of APVRS, a form of bacterial origin may set in, manifested by fever, worsening of symptoms after improvement, unilateral pathology, acute pain, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and reactive c protein (CRP). Overall, it is estimated that only up to 2% of viral upper respiratory tract infections are complicated by bacterial infection [

3].

In some cases, acute bacterial rhinosinusitis spreads to adjacent structures and may generate complications. The incidence of complicated forms is 3 cases per 1 million per year, predominantly in adolescent males, with an age-proportional course and prevalent in orbital districts [

3].

The two main routes of spread of bacteria infection from the sinuses to other sites are the direct route through congenital or posttraumatic dehiscences and the retrograde thrombophlebitis, predominantly through the ethmoidal veins [

4,

5].

There are basically 3 types of complications: orbital (OC, 60-80%), intracranial (IC, 15-20%) and osseous (5%) [

5].

Chandler's classification, despite dating back to 1970, is still the most widely used method to classify orbital forms and distinguishes preseptal cellulitis (type 1), orbital cellulitis (type 2), subperiosteal abscess (type 3), orbital abscess (type 4) and cavernous sinus thrombosis (type 5)[

6]. An additional presentation commonly considered as a complication of rhinosinusitis that does not fall under this classification is Pott's Puffy tumor (PPT), a lesion characterized by osteomyelitis of the frontal bone with associated subperiosteal abscess causing swelling and edema over the forehead and scalp and arising from frontal sinusitis or trauma.[

7]

Symptoms of a complicated form of rhinosinusitis are periorbital edema, displaced globe, double vision, ophthalmoplegia, reduced visual acuity, severe headache, bleeding, crusting, cacosmia, followed eventually by neurological symptoms of sepsis or meningitis [

3].

Management to identify a complicated form should always include a proper medical history collection, an objective examination aimed to detect orbital or intracranial complications, imaging and further targeted specialist evaluation.

Therapeutic management started with medical antibiotic steroid therapy it’s commonly enough to reach healing in preseptal cellulitis [

8], but surgical treatment may be necessary in other complicated forms refractory to medical therapy alone or in forms presenting with alarming features such as neurological symptomatology or visual function deficit.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was carried out between 2000 and 2023.

Twenty nine patients under 16 years of age who presented at a tertiary referral center with a sinonasal complicated acute rhinosinusitis were included in the study. We analyzed only patients which underwent surgical treatment.

Demographic data, physical examination findings, radiological imaging, source of the infection, complications, previous medical and surgical treatments and laboratory results were retrospectively investigated. Diagnosis was made by clinical and laboratory findings.

Primary outcome of the study was obtaining clinical demographic data and type of complication whereas the secondary purpose was to report our treatment algorithm.

Statistical analysis was made using computer software. Data were expressed as “mean” (standard deviation; SD), percent (%), minimum-maximum, Odds Ratio (OR); 95% confidence interval (CI) and “median” (Interquartile range; IQR) where appropriate p <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

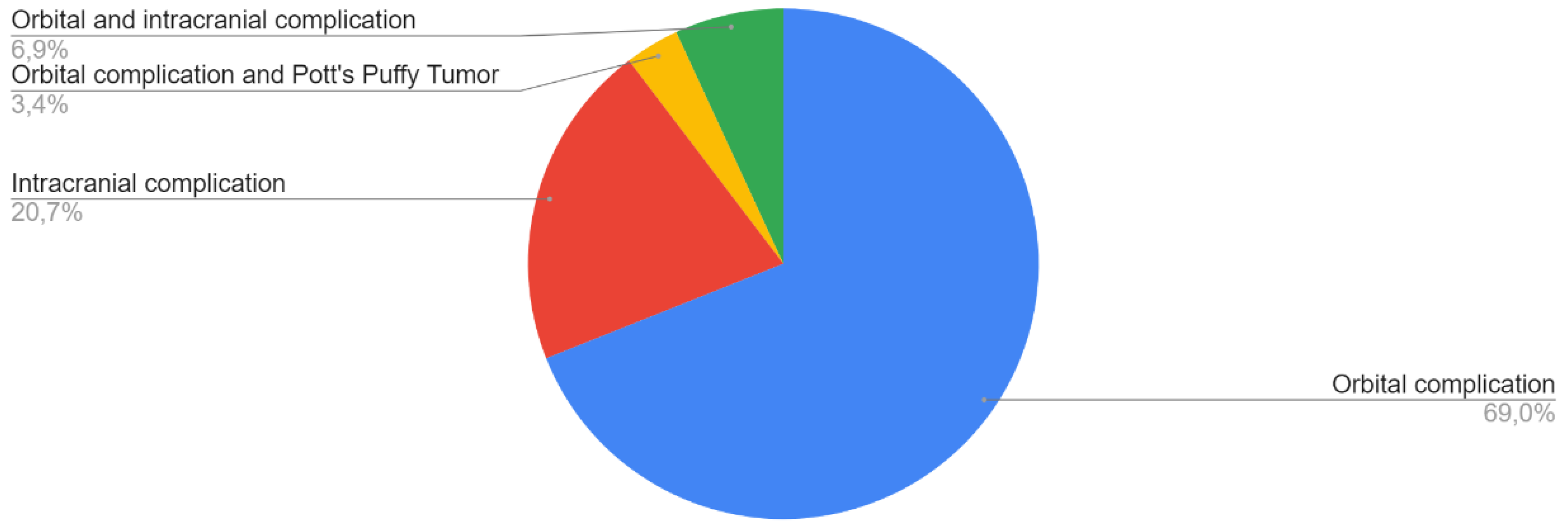

A total of 29 patients, 20 boys (69%) and 9 girls (31%) were included in the study. The median age was 13 years (± 6 years). The type of complication of acute rhinosinusitis is shown in

Figure 1.

The mean LOS for all patients was 11.75 ± 9.2 days.

Eighteen patients underwent preoperative CT scan (62,1%), one patient underwent a preoperative MR (3,4%) and ten patients underwent both CT scan and MRI (34,5%).

Patients in our study showed comorbidities such as allergy, asthma, Chron’s disease, obesity, adrenogenital syndrome, cystic fibrosis, hydronephrosis.

The main symptoms reported, regardless of the type of complication, were ocular edema/swelling in 23 cases (79%), headache in 22 cases (76%), RNO in 16 cases (55%) and fever in 15 cases (52%). Three patients (10%) reported facial paraesthesia, 3 patients (10%) reported drowsiness and 2 patients (7%) reported convulsions.

The principal long term symptoms reported are diplopia in five cases (17%) and hypovisus in 2 cases (7%).

In our series, only 12 patients (41,4%) performed nasal swab, which tested positive in 50% of cases, allowing to set up targeted antibiotic therapy.

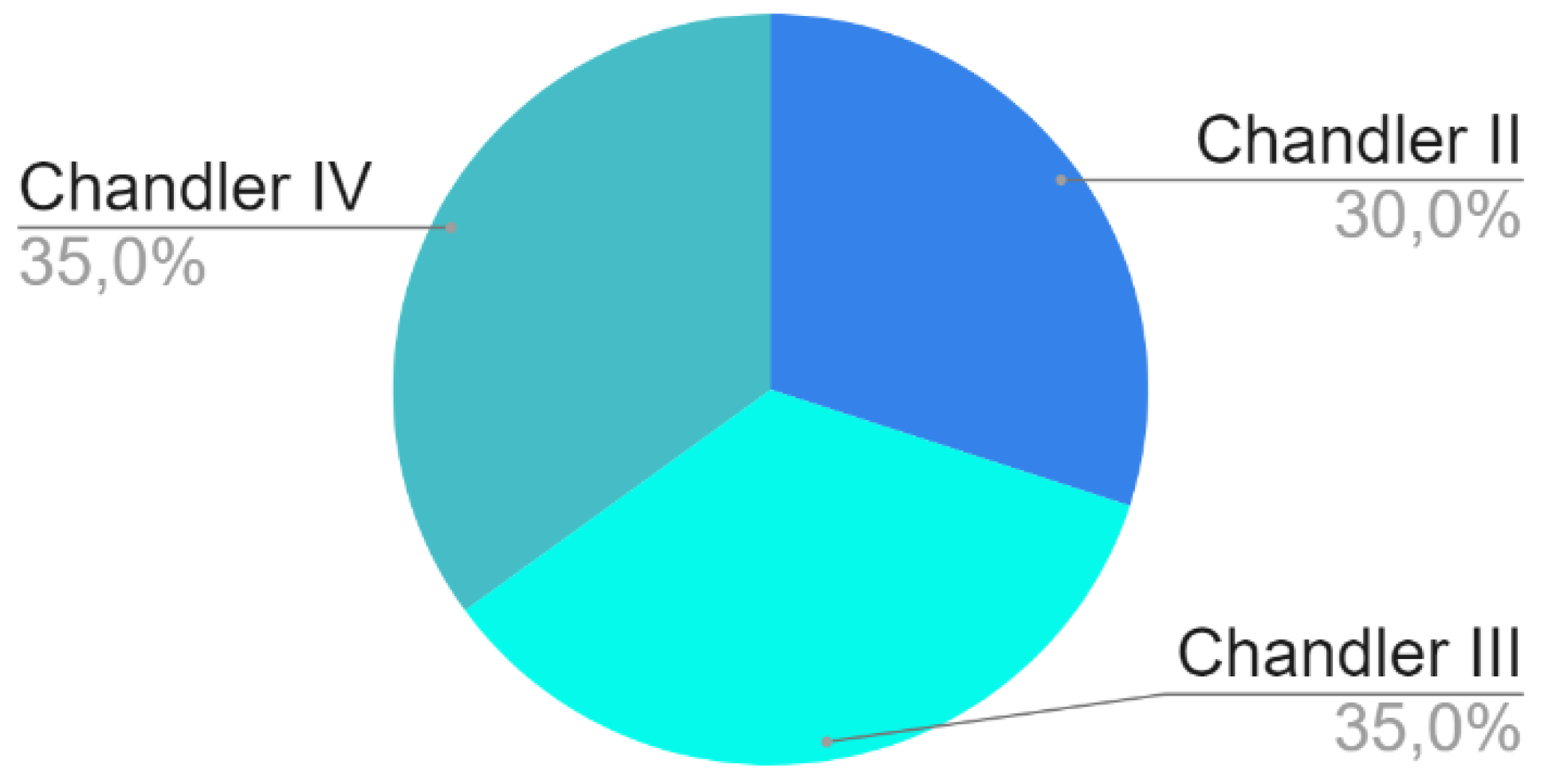

Twenty patients (69%) reported an exclusively orbital complication: these cases were classified according to Chandler's classification as shown in

Figure 2.

One patient, a 14-year-old male, presented with a Pott’s Puffy Tumor (PPT) accompanied by an orbital cellulitis (3%). He presented with RNO, headache and ocular swelling, and reported no long-term sequelae.

Thirteen boys and seven girls presented with an exclusively orbital complication, with a mean age of 13 years old (± 4,5 years). This group of patients presented with ocular edema (80%), RNO (55%), headache (55%), fever (45%), diplopia (20%) and hypovisus (10%). The comorbidity found was inhalant allergy (5%), asthma (5%), adrenogenital syndrome (5%), cystic fibrosis (5%) and hydronephrosis (5%).

An intracranial complication was found in 21% of patients (6 patients), 4 boys and 2 girls, mean age 13 years old (± 4,4 years).Two patients have an extradural empyema, 1 patient has a subdural empyema, and 3 patients have cerebral abscess. Two 16 years old boys had an orbital complication (subperiosteal orbital abscess) associated with an intracranial complication (7%).

The comorbidities reported in patients with exclusive or concomitant intracranial complication were allergies (12,5%), obesity (12,5%) and Crohn's disease (12,5%). The reported symptoms were headache (100%), fever (75%), respiratory nasal obstruction (50%), ocular edema (50%), drowsiness (25%), convulsions (25%), facial paraesthesia (12,5%) and diplopia (12,5%).

The principal reported symptoms are fever, RNO, headache, ocular edema/swelling, drowsiness.

A summary of demographic characteristics, comorbidities, symptoms and anatomical location and sites are listed in

Table 2.

The mean LOS and latency times between the onset of symptoms, surgical treatment and start of antibiotic therapy are shown in

Table 2.

Among patients with OC, 85% underwent endonasal endoscopic approach (functional endoscopic sinus surgery, FESS), 10% underwent superior eyelid approach, 20% underwent orbital decompression, 15% underwent orbital and external approach and no one underwent an exclusive external approach.

Orbital decompression was performed in presence of orbital cellulitis or periorbital orbital abscess with an intraconic compressive effect or vision impairment.

Patients underwent follow up evaluations for a median time of 15 months ( 1 month-11 years).

Forty-five percent of patients with exclusively orbital complication and/or PPT reported a long time nasal sequelae, such as chronic rhinosinusitis, respiratory nasal obstruction (RNO) or endonasal synechiae.

Neurosurgical intervention was necessary in the presence of neurological symptoms and evidence at MRI of subdural or extradural empyema, meningitis, cerebral abscess or meningeal thickening.

In these cases patients underwent follow up visits for a median time of 12 months ( 1 year-10 years).

Patients who reported exclusive or concomitant intracranial complications present neurologic sequelae (25%) and both nasal and neurologic complication(12,5%).

4. Discussion

Despite its high prevalence, incidence of complications forms is infrequent and most patients with acute sinusitis are treated effectively with medical therapy alone.

However, as a tertiary center we analyzed patients with complicated sinusitis which required surgery.

The possible drainage routes of an endonasal abscess collection are the medial one, for which an endoscopic endonasal treatment is adequate, the lateral one, for which drainage via

external via the upper eyelid technique, and finally the intracranial drainage route, the most fearful and the one associated with the greatest complications, which requires a transcranial approach in collaboration with neurosurgeons and with the aid of a neuronavigator.

The timing and criteria leading to surgery are controversial.

According to literature surgery is chosen in children non-response to medical therapy within 48 hours despite broad-spectrum antibiotics, or with documented subperiosteal or intraorbital abscess and reduced visual acuity/color vision [13,14].

Some authors suggest waiting 48-72 hours with medical examination therapy alone if vision is normal in case of subperiosteal abscess [

9].

We have analyzed 29 patients admitted in hospital for complicated ARS which required surgical therapy, predominantly males although intracranial complications were more frequent in girls. In accorance to litterature, all patients performed CT scan or MRI before the surgucal decision (cit).

The basal CT scan is simple to perform in the child and allows us to have a general picture of the situation and then subsequently perform an MRI under sedation to precisely identify the complication, being able to visualize the soft tissues which are the target direction of our gaze. .

In centers where MRI is not easy to access, a contrast-enhanced CT scan will be the first option.

The mean age of the patients was 13 years, in agreement with other articles in the literature.

Considering that our patients all underwent surgery, the distribution of the type of complication was coherent with litterature.

Chandler's classification mentions the orbital septum as a watershed structure, which is the membrane that connects the posterior aspect of the margins of the orbit with the tarsus. Since the orbit is therefore like a rigid box, an expansive phlogistic process in this location will determine a swelling of the orbit and adjacent structures.

Thanks to radiology, it is possible to identify the site of the phlogistic process and therefore trace each case to one of the chandler groups.

Analyzing the LOS, patients with intracranial complication had a higher value on average, due to the fact that they often remained in the ICU for a few days after surgery and the recovery time was longer.

Comorbidities were varied, with no particular frequency in one type of complication.

Patients with intracranial complication had predominantly headache but also nasal respiratory obstruction, while patients with orbital complication had nasal or ocular symtoms, in agreement with the literature.

Nasal swabbing was done in less than half of the cases and, when positive, allowed targeted antibiotic therapy to be undertaken. However, in those cases where it was not done, empiric antibiotic therapy was initiated and was still effective. In this regard, the guidelines, do not mention the nasal swab as an essential element in the setting of treatment, partly because of the technical time required to process the sample and the antibiogram.

In agreement with the literature, approximately 45% of patients with orbital complication reported long-term nasal symptoms, which however completely resolved.

Of the 4 patients who showed diplopia, only 1 showed it later and no patient who underwent a transcranial approach experienced neurological sequelae.

11.5% of patients had a flare-up after 1-4 years, and this is mainly due to some critical issues in the approach to the pediatric patient, such as the narrowness of the anatomical spaces.

The patient with Potts poffy tumor, a 14-year-old male, presented the classic symptoms reported in the literature (RNO, headache, ocular edema/swelling, with a hospitalization time intermediate between an orbital and intracranial complication but a high latency time between the onset of symptoms and surgery.

Patients who were treated both surgically and medically with subperiosteal and orbital abscess were hospitalized significantly longer than patients.

5. Our Algorithm and Conclusions

Given that complicated acute rhinosinusitis is a rare event, the management to identify a complicated form should always include a correct anamnesis, a physical examination aimed at identifying orbital or intracranial complications, which therefore evaluates ocular motility, color vision, and signs of bacterial infection, blood chemistry tests especially aimed at evaluating the leukocyte formula and inflammation indices, and if necessary imaging and further targeted specialist evaluation.

When should we think that acute rhinosinusitis is becoming complicated?

Among the various symptoms present in the literature, in our series the most frequent were orbital edema, headache, fever, diplopia, followed by neurological symptoms such as seizures, focal deficits or hypovisus.

(Neil F. et al. A guide to the management of acute rhinosinusitis in primary care management strategy based on best evidence and recent European guidelines .British journal of general practice.611-613 Nov 2013)

Furthermore, in the case of pediatric patients our attention must always be directed to a possible deficient immune system.

When should you decide to hospitalize the patient?

There are no essential criteria, but based on our clinical experience and the possibilities offered by our center the hospital admission criteria have been

When should surgical intervention be necessary and when can we continue with medical therapy?

In the case of a preseptal form, surgical treatment is almost never resorted to.

In our experience, surgical therapy has been resorted to in cases of

- -

Worsening of orbital signs after 48 hours of antibiotic therapy and CT evidence of abscess

- -

Visual worsening of symptoms

- -

The dimensions were not included in the surgical intervention criteria as the symptomatic picture prevailed in our clinical practice

References

- Turhal G, Göde S, Sezgin B, Kaya İ, Bozan A, Midilli R, Karcı B. Orbital complications of pediatric rhinosinusitis: A single institution report. Turk J Pediatr. 2020;62(4):533-540. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu PW, Lin YL, Lee YS, Chiu CH, Lee TJ, Huang CC. Predictors of Surgical Intervention for Pediatric Acute Rhinosinusitis with Periorbital Infection. J Clin Med. 2022 Jul 1;11(13):3831. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology. 2020 Feb 20;58(Suppl S29):1-464. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser A, Fogarasi S. Periorbital and orbital cellulitis. Pediatr Rev. 2010 Jun;31(6):242-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velayudhan V, Chaudhry ZA, Smoker WRK, Shinder R, Reede DL. Imaging of Intracranial and Orbital Complications of Sinusitis and Atypical Sinus Infection: What the Radiologist Needs to Know. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2017 Nov-Dec;46(6):441-451. Epub 2017 Jan 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler JR, Langenbrunner DJ, Stevens ER. The pathogenesis of orbital complications in acute sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 1970 Sep;80(9):1414-28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma P, Sharma S, Gupta N, Kochar P, Kumar Y. Pott puffy tumor. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2017 Apr;30(2):179-181. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santos JC, Pinto S, Ferreira S, Maia C, Alves S, da Silva V. Pediatric preseptal and orbital cellulitis: A 10-year experience. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019 May;120:82-88. Epub 2019 Feb 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turhal G, Göde S, Sezgin B, Kaya İ, Bozan A, Midilli R, Karcı B. Orbital complications of pediatric rhinosinusitis: A single institution report. Turk J Pediatr. 2020;62(4):533-540. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).