1. Introduction

Intonation plays a significant role in shaping utterances with various meanings, involving grammatical, attitudinal, accentual, and discourse meanings (Roach 2002). To convey speakers` messages effectively, they need to utilise correct intonation patterns. Selecting an incorrect intonation pattern may lead to misunderstandings or offence, which in turn, causes improper or at best unnatural communication. Although native speakers of English and Kurdish have no difficulties in using different intonation patterns in their languages to express boredom, learning the intonation patterns of one language may systematically help grasp the other's intonation patterns. Suppose non-native speakers of any one of these two languages are not attuned to the other language's intonation patterns. In that case, they may face problems in communication or at least their conversation would be unnatural.

Over the last decades, many studies have investigated various attitudinal functions of intonation in English and many other languages. Some of them have argued for the existence of intonation patterns being associated with certain attitudes (Al-Bazzaz & Qadir 2016; Qadir 2011). Others believe the other way round, that is, emotions shape intonation patterns (Bänziger and Scherer 2005). Yet other studies (Pakosz 1983) have claimed that intonation only conveys information concerned with the amount of emotional arousal. Accordingly, elements of the context in which the statements are uttered and/or the information obtained by other channels, namely loudness, tempo, gestures, and facial expressions, among others, are needed to disambiguate particular emotion categories (Roach 2002). Therefore, the present study considers not only pitch-related factors with which an utterance is produced when expounding the boredom function in the two languages; instead, it includes the other elements such as loudness, tempo, and facial expressions. This study would be the first to discuss the boredom function of intonation in Kurdish using authentic material, that is, Kurdish films and recorded material, and compare it to the data available in English. Thus, the aim behind researching this topic is twofold: First, it seeks to establish the types of tone, the height of pre-head and head, the key, and the width of pitch range in certain sentence types used in the expression of boredom in both Kurdish and English. Second, it aims to pinpoint the other prosodic factors that go along with the above ones in conveying the emotion in question. The expectation is that the tone patterns used to express boredom in Kurdish are strikingly similar to those of English. Yet, prosodic features such as loudness, tempo, and facial expressions are essential in expressing boredom.

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

2.1. Prosodic Cues Used to Express Emotions and the Most Dominant One(s)

Communicating emotions is essential for everyday interaction. Besides, how these emotions are conveyed is also vital for relationships among individuals in a society. Communication is transmitting and receiving messages that help human beings to share information and attitudes or emotions. A source sends a message through a communication channel which then is sent back by the receiver through the same communication channel. The medium through which emotions are conveyed in this research is intonation.

Intonation can disclose ambiguous utterances, and it is used for a variety of purposes, among which the most predominant is revealing the speakers' attitudes or emotions. The improper use of intonation leads to baffling communication. It may have a great negative impact on the interpretation and even the intelligibility of the message. Consequently, the speaker may offend or be misunderstood.

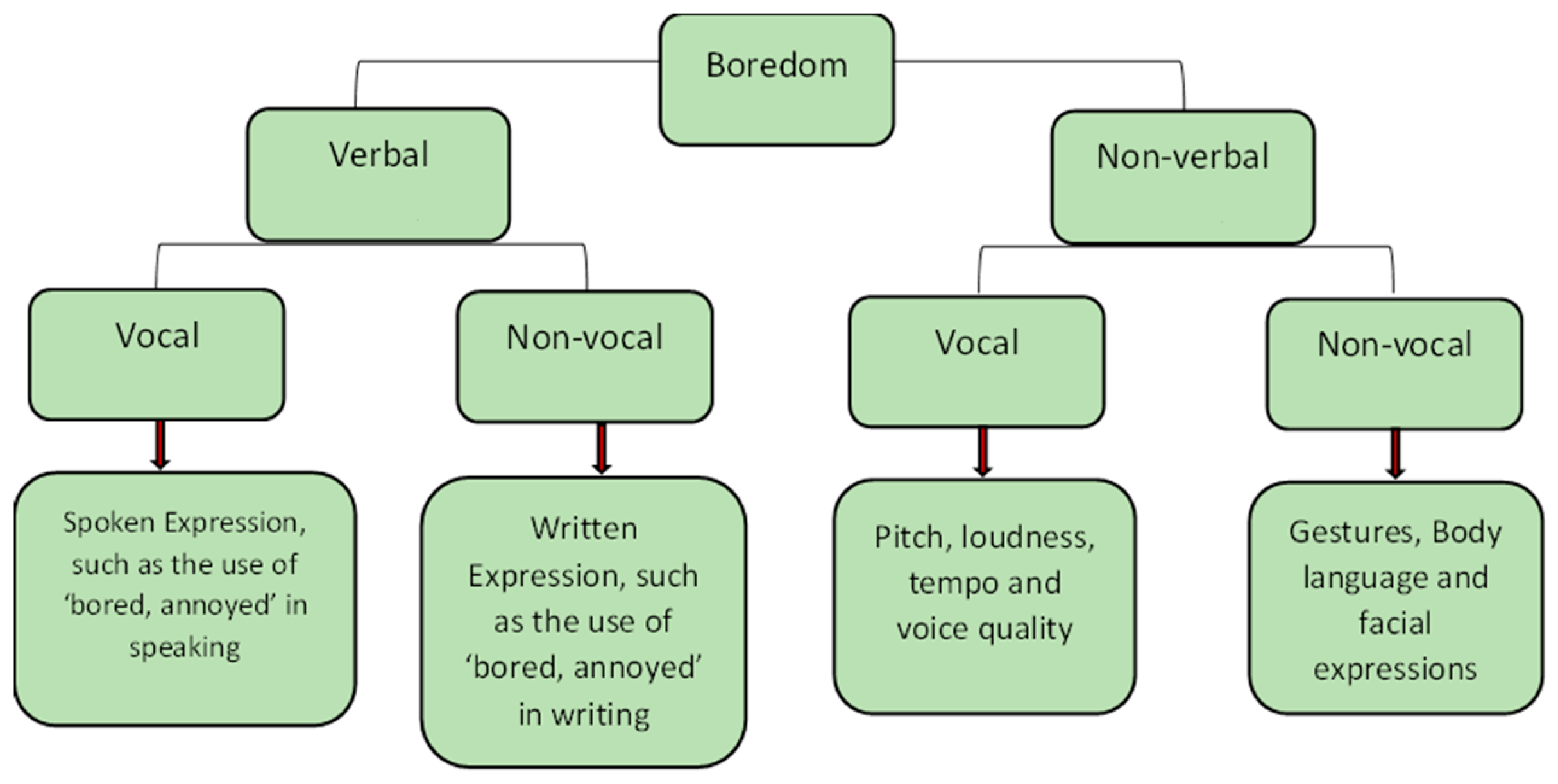

Any communication can be either verbal or non-verbal (Crystal 2003). In light of this, the communication of any emotion can be either verbal or non-verbal. The verbal communication of emotions includes the use of certain expressions which carry the feeling in question. For instance, there are lots of literal expressions (such as irked, bored, annoyed, etc.) and figurative expressions (such as bored to death to mean very bored) in English, which can be used for expressing boredom (Fussell 2002). The verbal expression of boredom can be vocal (which is the spoken expression of boredom) or non-vocal (the written expression of boredom). The latter is the one that is not concerned with this work. Boredom can also be conveyed non-verbally, and this can be expressed in two ways: vocally or non-vocally. The non-verbal vocal expressions of boredom are the use of (pitch, loudness, tempo, voice quality, and so on). In contrast, the non-verbal non-vocal expressions of boredom focus on (gestures, body language, and facial expressions). Therefore, a host of devices exist for signalling emotions in general and boredom in particular (Sauter 2006). Consider the following diagram, which summarises the above information and illustrates the different channels of expressing boredom:

Figure 1.

Different channels of expressing ‘boredom’.

Figure 1.

Different channels of expressing ‘boredom’.

Silvia (2006) mentions that recognising emotions from vocal cues are high, but he also affirms that not all emotions are identified equally well. He cites a study by Banse and Scherer (1996), who have concluded that emotions like hot anger, boredom, and interest can accurately be recognised while emotions such as disgust and shame cannot be identified well. As far as the confusion of emotions was concerned in their study, it was revealed that “the vocal expressions of interest were most often confused with happiness” and “expressions of boredom were most often confused with sadness” (Banse and Scherer 1996, p. 35).

Though human beings have a rich repertoire of signals to communicate emotions or attitudes, some of them are more important than others. In line with this, based on the literature reviewed by Mozziconcci and Hermes (1997), global properties such as pitch range, pitch level, and speech rate are more pivotal to the expression of emotions than the other cues. However, according to Gimson (1970), the type of the nucleus, the words a speaker uses, speech rate, whether the airstream is ingressive or egressive, range of intonation, whether the pitch level is continuous or not, and the pitch height of the pre-head and head; all these participate in expressing emotions. Ma (2012) considers tone, head, pitch range, and nucleus placement to be the most important clues to convey emotions. Sauter (2006) believes that the cues used to identify emotions vary, but he also thinks that pitch and pitch variation play a central role. Besides, Johnstone and Scherer (2000, p. 6) generally categorise the dimensions of vocal expressions, that is, the cues used to convey emotions into three categories: time measures which concentrate on “the durations of sounds and pauses in speech, and the overall speech rate”, intensity measures which concentrate on “the energy in the speech signal that affects the perceived loudness of speech”, and frequency measures which concentrate on “the pitch of the voice, quantified as the rate at which the vocal folds open and close, ... the base level of the pitch, the range of the pitch, and the variability of the pitch during the utterance” (as cited in Silvia 2006, 19). Finally, Chun (2002) thinks that the most influential parameters on listeners’ ratings are tempo and pitch variation. To sum up, there are many devices to communicate emotions or attitudes. One can conclude that pitch level, pitch direction, and pre-nucleus pitch patterns are the central ones.

2.2. Intonation as a Channel of Communicating Emotions

Studies and observations of communicating emotions via intonation in English are quite old and tautological compared to those of Kurdish. A flurry of both theoretical and practical studies has investigated the role of intonation in manifesting emotions in English. There is no controversy about the expression of emotions via intonation in both languages, English and Kurdish. Whether intonation per se can convey emotions or attitudes or one-to-one correspondence between intonation patterns and emotions has generated heated controversy in English and most other languages like Dutch, and Chinese. Besides, most studies have confirmed that intonation can perform this role along with other prosodic features such as loudness, timing, tempo, and other paralinguistic features. In this respect, there are figure scholars in phonology and phonetics, such as O'Connor and Arnold (1973), who ascribe certain emotions to specific intonation patterns. However, Bänziger and Sherer (2005) object to this kind of approach and point out that the utterances' verbal content often conveys the meaning that the intonation pattern is supposed to represent.

Mozziconacci and Hermes (1997), in both a production and perception study in Dutch, reached three important conclusions about the correspondence between specific intonation patterns and the discrete emotions they express. First, they affirm that there is no direct coupling between the intonation patterns and the emotions they manifest, that is, one pattern is realised in the expression of more than one emotion and vice-versa. Second, they find that there exist specific intonation patterns with particular emotions, but the number of these is limited compared to those with more than one identified emotion. Third, they state that some intonation patterns are more suited to signal certain emotions than others.

In another study, Ma (2012) showed that the performances of Chinese speakers of English were worse than those of the native speakers in conveying specific emotions. In that study, the intonation performances of twelve participants, ten Chinese students, and two Native American English speakers were explored. Five of the ten Chinese students were non-English-major sophomores, and the other five were sophomore English majors. Twenty-nine sentences from previous relevant studies were chosen as the recording material to perform nineteen emotional functions. Then, four American teachers listened to the recordings and graded the participants' intonation performance according to a five-point Likert scale. The speakers' specific intonation characteristics of the nineteen emotions were analysed with the assistance of software. The results showed that the Chinese speakers' performance grades were much lower and worse than that of the native speakers and the intonation performances of the non-English-major learners were worse than that of the English majors. This is due to the fact native speakers are quite familiar with their mother tongue. Whereas, the Chinese speakers are not familiar with the conventions of the English intonation system.

2.3. The Impact of the Wrong Use of Intonation Patterns on Emotional Communication

Intonation can remove ambiguity and is one of the aspects of speech without which one can never speak like a native speaker. Moreover, foreign English speakers cannot acquire a native-like authentic intonation if they are not exposed to authentic native speakers’ intonation thoroughly. Therefore, they cannot communicate emotions, or, if they can, they are interpreted as rude or unintelligible. According to various data, the inappropriate use of intonation patterns leads to conversational misfires or misinterpretations of emotions. Coelho and Rivers (2004, 62) state, “When the intonation patterns of a language with a greater range of pitch are applied to English, the effect may be disconcerting to English speakers”. That is, if an English utterance is pronounced with a higher or lower pitch by a foreign speaker of English, the speaker may give a different emotion, or he may sound impolite. For instance, “speakers of those languages in which the range of pitch is narrower than in English, may sound bored or uninvolved - to English speakers” (Coelho and Rivers 2004, 62).

An excellent example of the effect of the wrong intonation is given by Dubinsky and Holcomb (2011) as well as Pavlenko (2009) who narrate the story of a linguist who studied the intonation of a group of food servers at a British cafeteria. Some of the servers were native English speakers, and some of them were Indian and Pakistani immigrants. The British servers would employ the rising tone when they offered the customers an item, while the Indian and Pakistani servers used the falling tone. This misuse of the appropriate tone pattern caused the customers to complain and state that the Indian or Pakistani servers were rude and unfriendly. This interpretation is because the falling tone was the appropriate tone for the same purpose in Indian or Pakistani.

According to Chun (2012), Loveday (1981) investigated the role of sex on pitch and politeness both in Japanese and English. He found that Japanese males have a lower pitch level and pitch range than their English counterparts, while Japanese females have higher pitch levels and pitch ranges than their English counterparts. Thus, when Japanese males transfer their lower Japanese pitch levels and range to the English formulas, it causes misunderstandings on the part of the English native speakers, or it is interpreted as impolite or cool since low pitch range is used to express boredom in English. In the same vein, German male speakers sound bored to British listeners because they have lower pitch levels than the British speakers and British females seem to be aggressive to the German listeners as they have higher pitch levels than the German females. These misjudgements of emotion occur due to different pitch height levels in various languages (Hirst and Cristo 1998).

2.4. The Tone Patterns and the Cues Used to Express Boredom in English

Boredom is the feeling that a person experiences when he is tired or sick. For instance, “an uninspired lecture elicits boredom which produces a yawn” (Russell 2003, 339). In the expression of any emotion, several factors contribute to the expression of that emotion. The most relevant one(s) is, firstly, the sequential components of a tone pattern which include pre-head, head, tonic syllable, and tail. Secondly, the prosodic elements like the width of pitch range, key, loudness, and speed influence the expression of emotions. Finally, paralinguistic features such as facial expressions, gestures, and body movements (See Roach 2002, 183-190).

As far as the sequential components of a tone pattern are concerned for communicating boredom in English, no mention of pre-head has been made in the literature to the researchers' best knowledge. There are several accounts for head and tone, and each one cannot be accurate unless the syntactic category of the utterance is taken into account. This is because a tone used to express boredom in a statement is not necessarily used to express boredom in a Yes, No, question and vice-versa. O’Connor and Arnold (1973) state that the low drop tone, similar to the low fall tone, is used to signal dullness (boredom) among several other emotions that are close to boredom, such as coolness, dispassionateness, grimness, and surliness in statements having no head, e.g.

1. A) “what is your name?”

B) “\Jonson.”

This is fairly consistent with Bolinger (1986, p. 230) who affirms that a low flat monotone style can be used to convey routine boredom in statements, e.g.

2. “It’s the same old \thing.”

A plain falling pattern, in which the voice does not rise on the tonic but remains flat and then falls either within the final syllable or on the following, is also employed to convey boredom or lack of enthusiasm (Ponsonby 1982, p. 108). However, according to Gimson (1970, p. 281), the low-rising nucleus with a low head is also used to show boredom in statements, e.g.

3. “It’s ׀ not im/portant.”

Gimson (1970, p. 279) also indicates that the low fall tone is used to convey boredom in Wh-questions having a low head. Here, the low head throws the nucleus into greater prominence and often shows a lack of interest.

4. “׀ What are we going to \ do?”

Gimson (1970, p. 281) further states that the low-rise tone with a low head in Yes, No, questions can also be used to show boredom, e.g.

5. “Can you ׀ come / next week?”

Crystal (1969, p. 305) also asserts using the rising tone to communicate boredom. Wells (2006), on his part, affirms this and states that an independent elliptical question is pronounced with a Yes, No, rise to express boredom. An independent elliptical question is a short Yes, No, question and a way of reacting to a statement made by another speaker. It is different from a tag question in that it involves a change of speaker (Wells, 2006, p. 52).

6. A) He’s ׀ just seen \ Peter.

B) / Has he?

This is a short response to keep the conversation going. And, the pitch range is important here, which is narrow since it may indicate surprise with a wide pitch range.

Crystal (1969), on the other hand, affirms that in non-subordinate structures, the level tone can be used to express boredom among several other emotions or meanings. In addition to this, Bolinger (1986) states that level and down-tilt tones are used to express boredom. As regards tail, Crystal (1969) mentions that tail in English tone units is usually non-contrastive. However, it is wrong for him to deny any contrastivity. He affirms that if a tail continues the pitch direction of a falling tonic syllable first and then levels out, it may communicate boredom and other attitudes such as irony or sarcasm. This type of tail, according to Crystal, is known as “an attitudinally marked form of tail”.

Regarding prosodic components of intonation, there exist various but similar accounts. Chun (2012) indicates that native English speakers generally use low intonation contours to convey boredom. This is fairly compatible with Bolinger (1986), who states that low pitch is normally used to express boredom in English. Wichmann (2000) also says that a stretch of speech with a low, narrow pitch range and negative signals might indicate boredom or gloom. Furthermore, Bolinger (1972) asserts that the pitch range will shrink for boredom, that is, it declines. Besides, Liscombe (2007) puts forth the idea that boredom is one of the emotions that is expressed by low mean fundamental frequency, low fundamental frequency variability, low-intensity variability, and slow speaking rate.

Crystal (1969) shows that factors such as high unstressed syllables, drawled syllables, flattened syllables in the tail, a narrow pitch range, a slow tempo, and lax tension are indicators of boredom. Silvia (2006) states that a slow tempo and monotony express boring speech. Further, they add that the base level of pitch and speech rate decline, and the voice’s pitch becomes less variable and shows a smaller range of frequency. Chun (2012) finds that moderate pitch variation and slow tempo usually convey unpleasant emotions, such as sadness, disgust, and boredom. Gimson (1970) asserts that a slow delivery rate is used to express boredom in statements. He also states that an ingressive airstream with friction at the rounded lips and a falling pitch produced by adjusting the mouth cavity and the tongue movement are used to signify pain. Moreover, the utterance may be punctuated by sighs that denote boredom. Mozziconacci and Hermes (1997) have demonstrated that the pitch range and pitch level are relatively low for boredom compared to other emotions such as fear, anger, sadness, happiness, and indignation in Dutch.

To sum up, boring speech is monotonous, and low intonation contours contribute to its expression. As for tones, falling, rising, and level tones are employed to convey boredom in English. The head is usually low, and the pitch range is narrow. Besides, there is a slow tempo and less variability in pitch.

4. Data Analysis and Results: The Expression of Boredom through Intonation in Kurdish

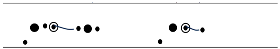

In this section, the expression of boredom in Kurdish through various intonation parameters such as the type of tone and pre-head and head height is analysed. The results are demonstrated. Furthermore, the role of several other prosodic factors such as the width of pitch range, key, loudness, and speed is demonstrated. Besides, paralinguistic factors such as gestures, body language, and facial expressions are taken into account in the analysis. The analysis also takes into consideration the syntactic category and markedness of the utterances. The following is the analysis of sixteen tone groups in different syntactic categories in Kurdish. The script between the slashes is the spoken version of the utterance in Kurdish, that is, the pronunciation. The symbols and diacritics involve the auditory analysis of the utterance. The number on the left is the number of the utterance, while the number on the right is the source of the data referred to in the methodology section. The translation of the sentence into English has been provided withing parentheses.

4.1. Statements

1. //wəła xəlasm kɪrdijə / 2. /tʃi waj nmajə//

(I have finished it, indeed! There is not a lot remaining.) (1)

The speaker’s tone and facial expression imply that (The speaker is tired and has been selling string beans all day; therefore, he is in a hurry to go home and rest. Besides, he wouldn’t like to say anything since he is tired). Here, the speaker answers a question which is a routine question.

The utterance is composed of two-tone groups. The first is pronounced with a level tone, which is the usual tone for routine answers. The pitch of the tonic syllable begins from mid and stays on the same level. The low pre-head and the mid-monotonous head increase the degree of boredom. The key is also mid, and the pitch range is very narrow, which shows the speaker’s tiredness. The tone group is unmarked concerning both tonality and tonicity. Thus, markedness plays no role in conveying boredom in this tone group. The second tone group is similar to the first in all respects. Both tone groups are also produced with low loudness and a relatively slow tempo. The speaker’s eyes are partially closed, and his shoulders are slumped.

3. //ʔaj babə mandi:mə// (Oh, dad! I am tired!) (1)

The speaker has returned from work, and he feels bored because he is tired and has pain in his body. His exhaustion makes him pronounce the tone group with a very low fall tone; the pitch descends from below mid to low. The head and the key are below mid, and the pitch range is very narrow. A physical and psychological explanation for this is that the vocal cords' low active muscles can make a narrow pitch range. This inactivity is due to the harmful physical state and the bad psychological affair of the speaker. Thus, when someone is tired, for example, the frequency of the vibration of the vocal folds will decrease, which in turn causes a low pitch level and narrow pitch range. Besides, the tone group is unmarked and pronounced with low loudness and a slow tempo as well as groaning and moaning of tiredness.

4. //hər mrdni teda nəbi/ 5. /i:ʃałła dem// (Except for death, I'll come, God willing.) (1)

The whole utterance is a complex sentence that comprises two unmarked tone groups. The first tone group is the subordinate clause, and the second is the main clause. The utterance situation illustrates that the speaker is bored to death because he has been indirectly asked to pay rent, and he is annoyed. The speaker understands and boringly affirms that he will visit him to pay the rent.

Both tone groups have the same characteristics. The speaker uses a mid-fall tone to show his boredom. He also uses a low pre-head, a mid head, a mid key, in addition to a narrow pitch range. The speaker, here, employs tentative and silent pauses between the two tone groups to show his boredom and hesitation. Besides, the utterance is pronounced with a low loudness and a normal tempo. Finally, there are also wriggles on the part of the speaker and wrinkles on his face. Moreover, his eyes are partially closed.

6. /taqəti hi:tʃm njə/ (I do not have the desire to do anything.) (2)

One of the Agha’s (owner of real estate and the head of a village in the past in Kurdistan) men has come to take the speaker to Agha because the speaker’s brother has beaten one of the Agha’s sons. The speaker does not know about this. The utterance implies that the speaker dislikes Agha’s men, and by seeing them, he gets bored.

To demonstrate his boredom, the speaker uses a mid-level tone. The pitch of the tonic syllable neither descends nor ascends, but it stays on the same level. The pitch range is very narrow; the head and the key are mid. The tone group is marked to focus on the word /hi:tʃ/ “anything” and to increase the effect of boredom. The tone group is also produced with some degree of loudness and a rather rapid tempo. Besides, the speaker’s movements are abrupt and substantial.

7. //bəxwaj tankjəkəm pe dəɡwaztəwə// (I am sure she makes me move the oil tank) (4)

The speaker’s boredom comes from an action or a habit of the addressee, which is repetitive. Therefore, he gets bored and will be tired of the addressee’s repetitive commands. The speaker expresses his boredom by using a mid-fall tone. The pitch of the tonic syllable descends from mid to low. The pitch range is narrow, and the head and the key are mid, but the pre-head is low. The literal meaning of this unmarked tone group also suggests boredom. Low loudness and a normal tempo accompany the above factors to reinforce the conveyance of the emotion in question.

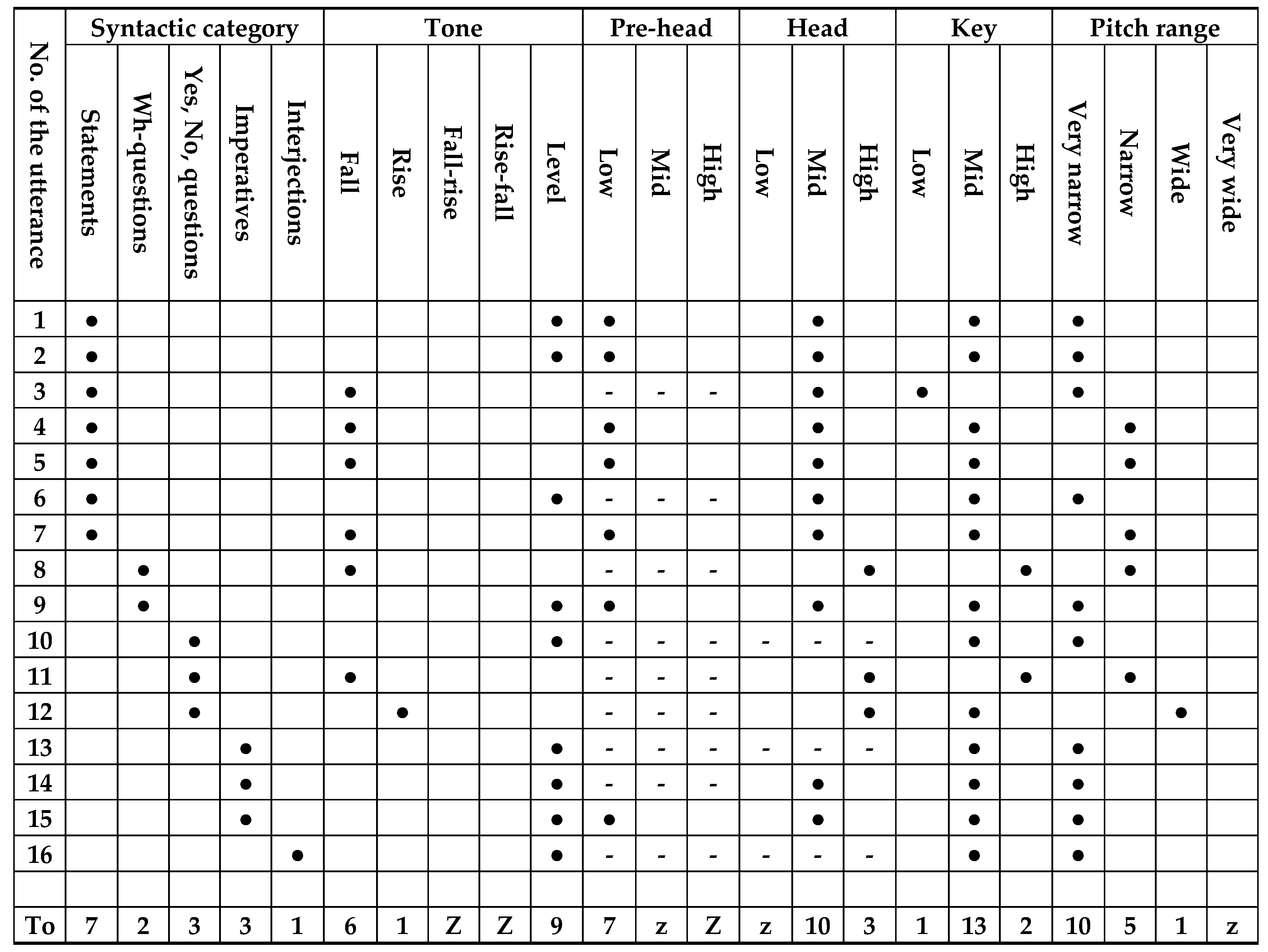

According to the above data and

Table 1, the statistics show the distribution of the parameters for analysing seven tone groups laden with the emotion in question in the following way. As far as tone is concerned with expressing boredom in statements, four of them (57.14%) are produced with mid-falling tones, and three (42.85%) are produced with mid-level tones. The data shows that the other tones are not familiar with this syntactic category to express boredom. As for pre-heads, the data show that five of the tone groups have low pre-heads, and the other two are pre-headless. The head also shows significant results; out of the seven statement tone groups with heads, six of them (85.71%) have midheads, but only one (14.28%) has a head below mid. The key also shows the same results as the head. It is mid in six (85.71) tone groups and below mid in only one (14.28%). It also clearly follows from the data that four (57.14%) tone-groups have a very narrow pitch range and the remaining three (42.85%) have a narrow pitch range.

Furthermore, most of the tone-groups (85.71%) are produced with low loudness except for one (14.28%), which is produced with some degree of loudness. Tempo, as another parameter, shows significant results; three (42.85%) tone groups are pronounced with a slow tempo, two (14.28%) with a rapid tempo and the remaining three (42.85%) with a normal tempo. Finally, according to the data analysed, the above factors are accompanied by several paralinguistic features such as slumped shoulders, half-closed eyes, wrinkles on the speaker’s face, groaning and moaning of tiredness, abrupt unsteady movements, and low active muscles of the vocal folds.

4.2. Wh-questions

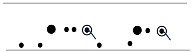

l8. //həwkə ʔətu: tʃɪt lə mɪn dəwe// (What do you want from me, now?) (2)

The boredom of this speech is since the addressee asks the speaker a series of questions, she will be annoyed by the addressee’s questions. The speaker uses the high to mid-fall tone to show her boredom because she wants to convey her most significant degree of boredom to the listener. The pitch of the tonic syllable descends from high to mid. This makes a narrow pitch range and a high key. The head is also high, which increases the degree of boredom. The tone-group is unmarked in terms of both tonality; the tone-group boundary coincides with the clause boundary and tonicity; because the interrogative word /tʃɪ/ is intoned, which is the most crucial word in the tone-group. The utterance is pronounced with low loudness, which also indicates boredom and a rather rapid tempo. Besides, the eyebrows are drawn together, and the speaker makes some erratic movements of the hand and body, in general. The utterance may show a kind of anger as well.

9. //ʔədi: tʃɪb kəm// (What shall I do then?) (3)

Here, the speaker gets bored because of the routines which occur in her life. The speaker is a woman, and she is busy with housework; she does the same things every day. Therefore, she is asked not to be very busy with the housework all the time and to enjoy herself sometimes. The speaker utilises a level tone to show her boredom. The pitch of the tonic syllable begins with mid and maintains the same level. The pitch range is very narrow, and the head and the key are mid, but the pre-head is low. The utterance is unmarked in terms of both tonality and tonicity. There is low loudness and a relatively slow tempo. Besides, her hands are separate, and there are sudden and unstable movements on the part of the speaker. These appearances show that the speaker is tired of the routines.

The above analysis and

Table 1 show two tone groups that have been selected to explicate this function in Wh-questions. The tonetic aspects and the pitch characteristics are as follows: One is produced with a falling tone, and the other with a level tone. The pre-head is low in one, and the other one is pre-headless. The head and the key are high in one tone group and mid in the remaining one. One tone group has a very narrow pitch range, and the other one has a narrow pitch range. Both tone groups are produced with low loudness. As for tempo, one tone group is pronounced with a rather slow tempo, but the rest is pronounced with a rather rapid tempo. Finally, there are abnormal hand and body movements, the eyebrows are drawn together and downwards, and the hands are pulled apart.

4.3. Yes, No, Questions

10. /səjda tʃətoj hinawə// (Did Sayda bring back Chato?) (2)

The speaker looks bored as he has been beaten, and suffers from pain in all his body. This makes him speak in a weary, monotonous, and tedious tone.

To show this feeling, the speaker employs the mid-level tone with a little bit rising. This results in a mid key and a very narrow pitch range. The tone group is pronounced with a very low loudness and a slow tempo. In terms of tonality, the tone group is unmarked, whereas, in terms of tonicity, it is marked to focus on the word /səjda/ and to know whether /tʃəto/ has been back or not. The use of the level tone with these syntactic structures is also marked because the utterance expresses boredom. Thus, the usual tone with Yes, No, questions in Kurdish is the rising tone, but since boredom is intended to be conveyed, a level tone is used here. Moaning is also used to express boredom here.

11. //ʔədi: xo mɪndari ʔaɣaj ləwi:ʃjan nadajə// (So, did the Agha’s children beat him, too?)

The speaker suffers from pain because he has been beaten to death by Agha. Now, he questions as to whether the Agha’s children have beaten his brother or not.

It sounds as if the utterance would contain three tone groups based on the clear pauses that exist between /ʔədi:/, /xo/, and /mɪndari: aɣaj ləwi:ʃjan nədajə/, but all of them compose only one tone-group. The word /ʔədi:/ in Kurdish is often used to begin with negative Yes, No, questions, and The word /xo/ is used in this utterance for addition, i.e., to add something to something else. The pauses that occur are due to the speaker’s physical and psychological state. The speaker has a lot of pain in his body, and he is bored with the social environment where he lives. The first two words of the utterance /ʔədi:/ and /xo/ are pronounced with lengthening and a rather level pitch, demonstrating the speaker’s inability to complete what he intends to say.

The tone that is used is the high fall tone. The pitch of the tonic syllable descends from high to mid. The head and the key are high, and the pitch range is narrow. The tone group is unmarked concerning tonality, tonicity, and tone. Besides, the tone group is produced with low loudness and a relatively slow tempo. There are also slow movements of the hand and the body as well as wrinkled face and moaning on the part of the speaker.

12. //bəran ʔəmɪn tʃma xami le nəxom//

(But is there anything left which I have not been sad for?) (3)

The speaker’s boredom is caused by having many problems and not being able to face them. The speaker uses a rising tone (glide-up). The tonic is below mid-rise. The pitch starts from below mid and goes up to nearly below high. The head is high, which decreases the tonic syllable's effect to manifest the strong attitudes like anger, surprise, and so on. The key is below mid, and the pitch range is rather wide. The tone-group is unmarked for tonality and tone, but it is marked in terms of tonicity because the speaker wants to express boredom by focusing on the word /tʃma/. It seems that the speaker’s sadness has been repetitive, and this causes boredom. Thus, one of the causes of boredom is the repetition of something. The utterance is also produced with low loudness and a rather slow tempo.

The above analysis and

Table 1 reveal that there is not only one tone in Kurdish associated with Yes, No, questions to indicate the present function. Out of three tone groups, one is produced with the level tone, one with the falling, and the other one with the rising tone. Besides, two tone groups have high heads, and one is headless. As for the keys, two have mid keys, and one has a high key. Furthermore, one tone group has a very narrow pitch range, one has a narrow pitch range, and the last one has a relatively wide pitch range. Concerning tonality, all the tone-groups are unmarked because the tone-group boundary coincides with the clause boundary in all of them. As for tonicity and tone, two tone groups are marked, and one is unmarked. Finally, all the tone-groups are pronounced with low loudness and a slow tempo as well as moaning, slow movements of the hand, and having wrinkles on the speakers’ faces.

4.4. Imperatives and commands

13. //waz bi:nə// (Stop crying and grieving) (2)

The speaker's boredom is due to his body pain since he has been beaten, and his fiancée cries for him. He tries to stop her. To show this, the speaker uses a level tone. The pitch of the tonic syllable begins with mid and remains on the same level. Accordingly, the pitch range is very narrow, and the key is mid. The tone group is unmarked concerning tonality, tonicity, and tone. In addition, it is produced with very low loudness and a languid tempo. Finally, the speaker pronounces the tone group with mumbling voice quality.

14. //ʔəre wazm le bi:nə// (I ask you to leave me) (2)

The boredom of this tone group is caused by repetition. The tone group has the same pitch characteristics as the previous one, i.e.; it is produced with the level tone. The head and the key are mid, and the pitch range is very narrow. The tone group is produced with low loudness and a slow tempo. Thus, the only difference between the present tone group and the preceding one is that this tone group has a mid head.

15. //ʔəj sɪndant leda ʔərewəła naxi:ndəwari/ (Do perish upon you, illiteracy!) (1)

The speaker cannot find one of the documents he needs because he is illiterate; therefore, he blames himself for not being literate. He gets bored of not finding the document and indirectly asks for illiteracy to be eradicated.

Here, the level tone is used with a bit falling, preceded by a mid-head and a low pre-head to indicate this feeling. The pitch maintains nearly the same level. The pitch range is very narrow, and the key is mid. The tone group is unmarked for tonality and tonicity but marked in terms of tone. It is also produced with low loudness and a very slow tempo. Besides, there are interruptions in the pitch of the speaker’s voice because of his psychological state. His eyes and mouth are partially closed, and there are wrinkles on his face. Moreover, his lips and organs of speech do not make regular movements. Finally, the speaker uses a creaky voice to express his boredom.

The above analysis and

Table 1 contain three examples representing boredom in imperatives, which are produced with level tones. Their key is mid, and their pitch range is very narrow. The second and the third tone groups contain a mid head, and all three tone groups are produced with low loudness and a slow tempo. They are unmarked with respect to tonality and tonicity. However, they are produced with a level tone to convey boredom. Sometimes, there are interruptions in the speaker’s pitch and voice qualities, such as mumbling and the use of creaky voice quality.

4.5. Interjections and Exclamations

16. /ku: pjawɪ korə dəkəj// (How you make people blind!) (1)

The speaker is illiterate. He cannot read and find the document that he needs. Therefore, he gets bored and blames himself and his illiteracy. The speech implies that the inability to read has occurred to him several times, and one of the causes of boredom is the repetition of something or an event.

The tone group is produced with the level tone; the tonic syllable pitch begins from mid and descends a little bit to below mid. The pitch range is very narrow, and the key is mid. The tone group has a long tail with monotonous stressed syllables. It is unmarked in terms of tonality and tonicity but marked in terms of tone because the level tone is used to convey boredom. The pitch of the tonic syllable starts from mid and descends to a bit below mid. Besides, the tone group is pronounced with low loudness, a plodding tempo, and creaky voice quality.

The above data and

Table 1 reveal the total results for expressing boredom in Kurdish as follows: Out of sixteen tone groups chosen for this function, seven (43.75%) are statements, two (12.5%) of them are Wh-questions, three (18.75%) are Yes, No, questions, three others (18.75%) are imperatives, and the remaining one (6.25%) is an interjection.

As for tone, nine (56.25%) tone groups are produced with the level tone, six (37.5%) are produced with the falling tone, and the remaining one (6.25%) is produced with the rising tone. Pre-head also shows significant results, which is usually low. Seven pre-heads (43.75%) are low, and the other nine (56.25%) are without pre-head. The heads are distributed this way: Ten heads are mid (62.5%), three are (18.75%) high, and the rest are without the head. The key is mid in thirteen (81.25%) tone groups, high in two (12.5%), and low in only one (6.25%) tone group. The pitch range is also essential for expressing boredom which is very narrow in ten (62.5%) tone-groups, narrow in five (31.25%), and wide in one (6.25%) tone-group.

Loudness and tempo play a vital role in conveying boredom. Within the entire set of the sixteen tone-groups, fifteen (93.75%) are produced with low loudness, and only one (6.25%) tone-group is produced with some degree of loudness. As regards tempo, eleven (68.75%) tone groups are pronounced with a slow tempo, three (18.75%) are produced with a rapid tempo, and the remaining two (12.5%) are produced with a normal tempo.

Other features were observed, during the analysis, that contribute to the expression of boredom such as facial expressions, gestures, body movements, and different voice qualities. These include the speaker’s partially closed eyes and mouth, wrinkles on his face, slumped shoulders, the muscles of the face and mouth are not actively involved in the production of the tone-groups, the speaker’s groaning and moaning, wriggly, abrupt and substantial movements of the body, drawing together of the eyebrows, separating hands, lengthening, mumbling and creaky voice qualities, and interruptions in the speaker’s pitch.

Above all, an ingressive air stream with friction at the rounded lips and a falling pitch produced by adjustment of the mouth cavity and by the movement of the tongue was noticed in the analysis that denoted boredom.

5. Comparisons and Conclusions

The present study tackled the role of intonation and other prosodic cues in expressing boredom in English and Kurdish. The English data was based on the literature available in English while the Kurdish data was based on the analysis given for sixteen tone groups in Kurdish. The following conclusions can be drawn from the analysis of the data in both languages.

1. According to the context of the utterances and the speakers` situations, boredom can best be defined as a low arousal emotional state caused by exhaustion, illness, pain or repetition.

2. To express or deal with boredom or any other emotion in any language, several factors should be taken into consideration simultaneously because one factor alone could not be considered a true reflection of the sentiment experienced. These factors can generally be classified into verbal cues and non-verbal cues, with each having vocal and non-vocal cues.

3. Boredom in English is communicated by low intonation contours. In other words, boring speech has a low monotonous flat style. To put it more clearly, low pitch, narrow pitch range, and less variability in pitch are common indicators of boredom. As far as tone is considered, the low falling tone with no head or a low head is used in both statements and Wh-questions. Besides, the low rising tone with a low head is employed in both statements and Yes, No, questions. Finally, the level tone is another tone which is used in English to convey boredom. Many other cues contribute to the expression of boredom such as, a tail which continues the pitch direction of a falling tonic syllable and then levels out, high unstressed syllables, flattened syllables in the tail, a slow tempo, and lax tension. In terms of acoustic features, low mean fundamental frequency, low variability in fundamental frequency, and low variability in intensity are other communicators of boredom.

5. The data analysis reveals that the level tone is the commonest tone used for conveying boredom in Kurdish. However, other tones, such as the falling tone, are also employed, especially in statements. The pitch of the falling tonic syllables usually dips from mid to low or to below mid. The rising tone is also used, especially in Yes, No, questions. The pre-head is typically low, the head and the key are usually mid, and the pitch range is very narrow, especially when the tone is level, and when the tone is falling, the pitch range is narrow. Besides, the pitch range may be wide if the tone is rising. The pitch range is never very wide here. Finally, slow speed, low loudness, lengthening and pauses accompany the above points.

6. As concerns paralinguistic features of the analysed data, it is observed that:

A. The speaker’s eyes and mouth are partially closed, and the face and mouth muscles are not actively involved in the production of the tone-groups. The speaker’s shoulders are slumped, his eyebrows are drawn together, and wrinkles are on his face.

B. The speakers produce the tone-groups with moaning and groaning, which is caused by restlessness. Mumbling and creaky voice qualities, and interruptions in the speaker’s pitch were also observed.

C. The speaker has wriggly, abrupt and substantial movements of the body and hands.

7. In both Kurdish and English, an ingressive air-stream with friction at the rounded lips and a falling pitch produced by different shapes of the oral cavity and the tongue's movement accompanied by some paralinguistic factors are also common for expressing boredom.

8. Both languages, Kurdish and English, are strikingly similar in several respects. Both use level, falling and rising tones, low pitch, narrow pitch range, and less variability in pitch to indicate boredom. Both use low loudness and a slow tempo. However, they are different in the pitch height of the head. In Kurdish, the head is usually mid, whereas in English, it is generally low.