Submitted:

07 August 2024

Posted:

08 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Recruitment and Data Collection

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.4. Survey Instrument

2.5. Statistical and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample Characteristics

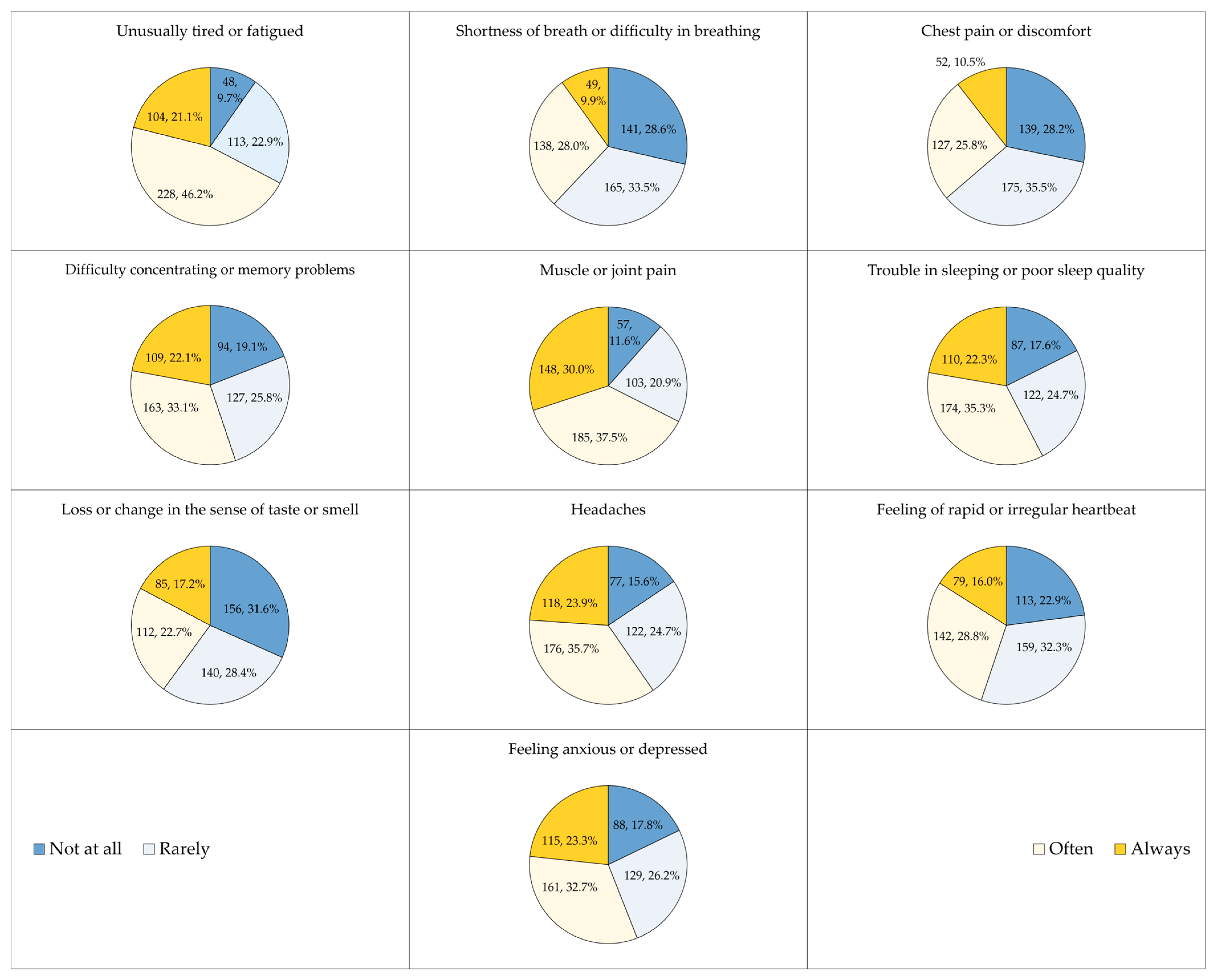

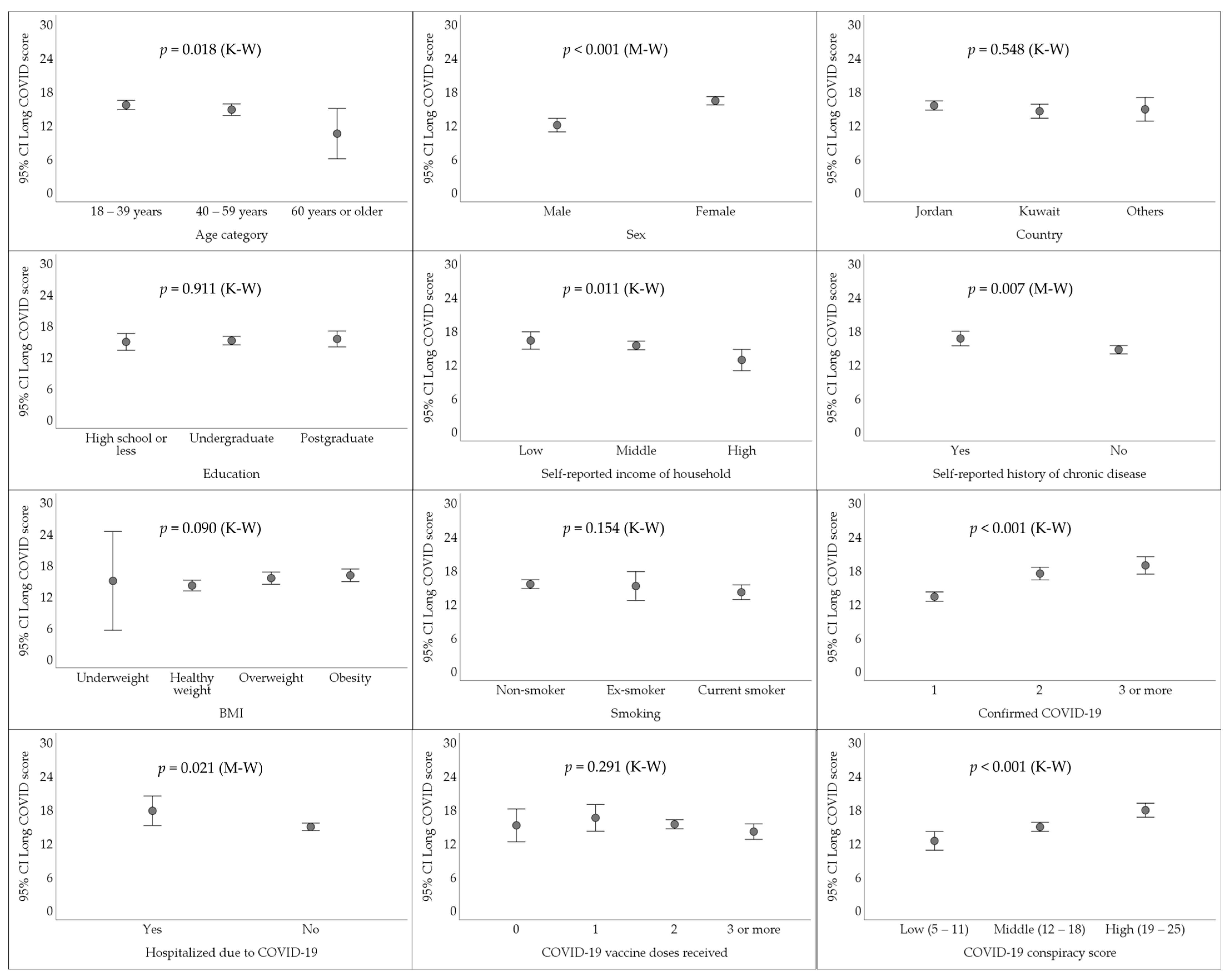

3.2. The Prevalence of Long COVID among Respondents Who Had Confirmed COVID-19 Diagnosis

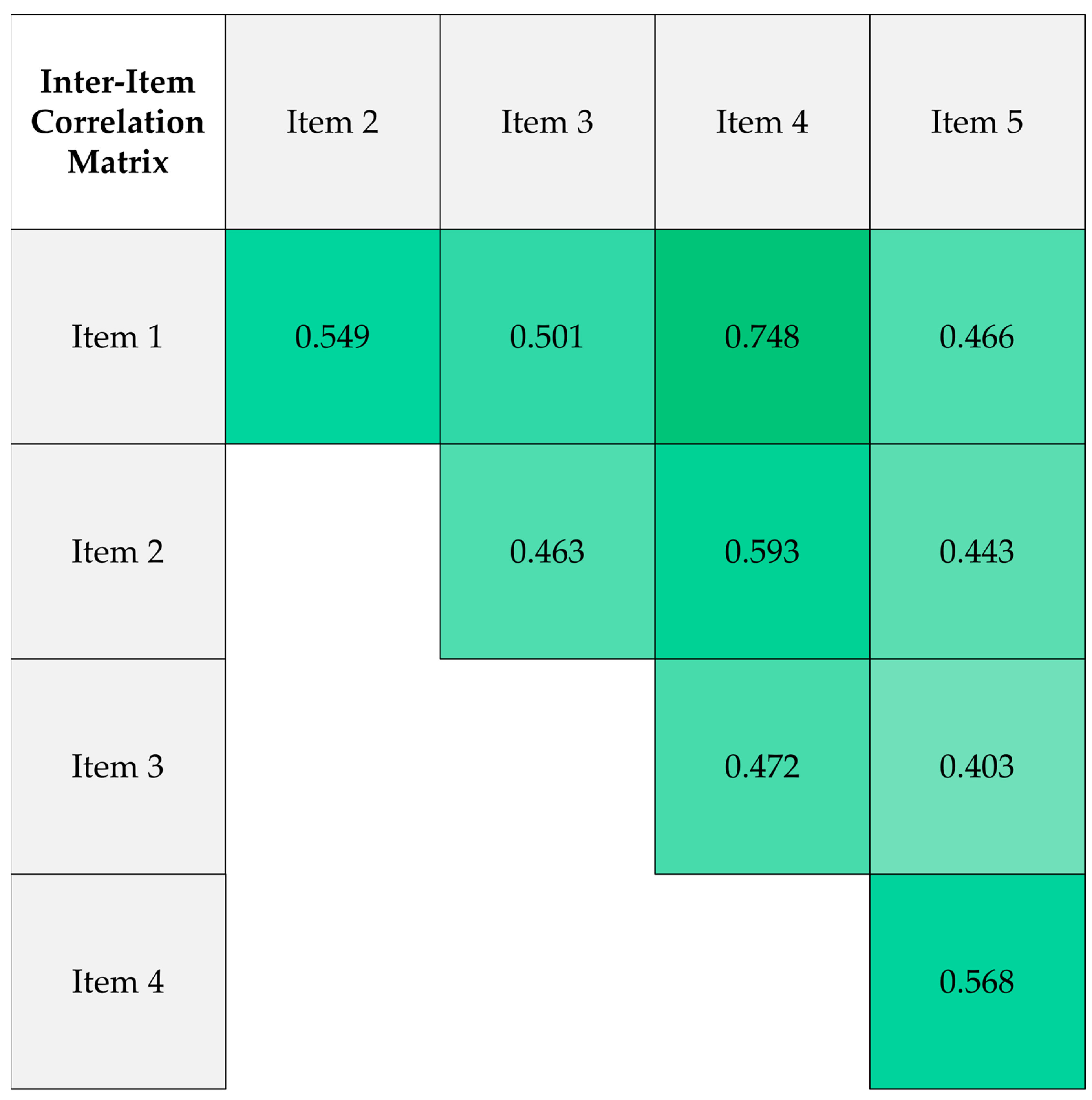

3.3. Reliability of the Conspiracy Belief Scale

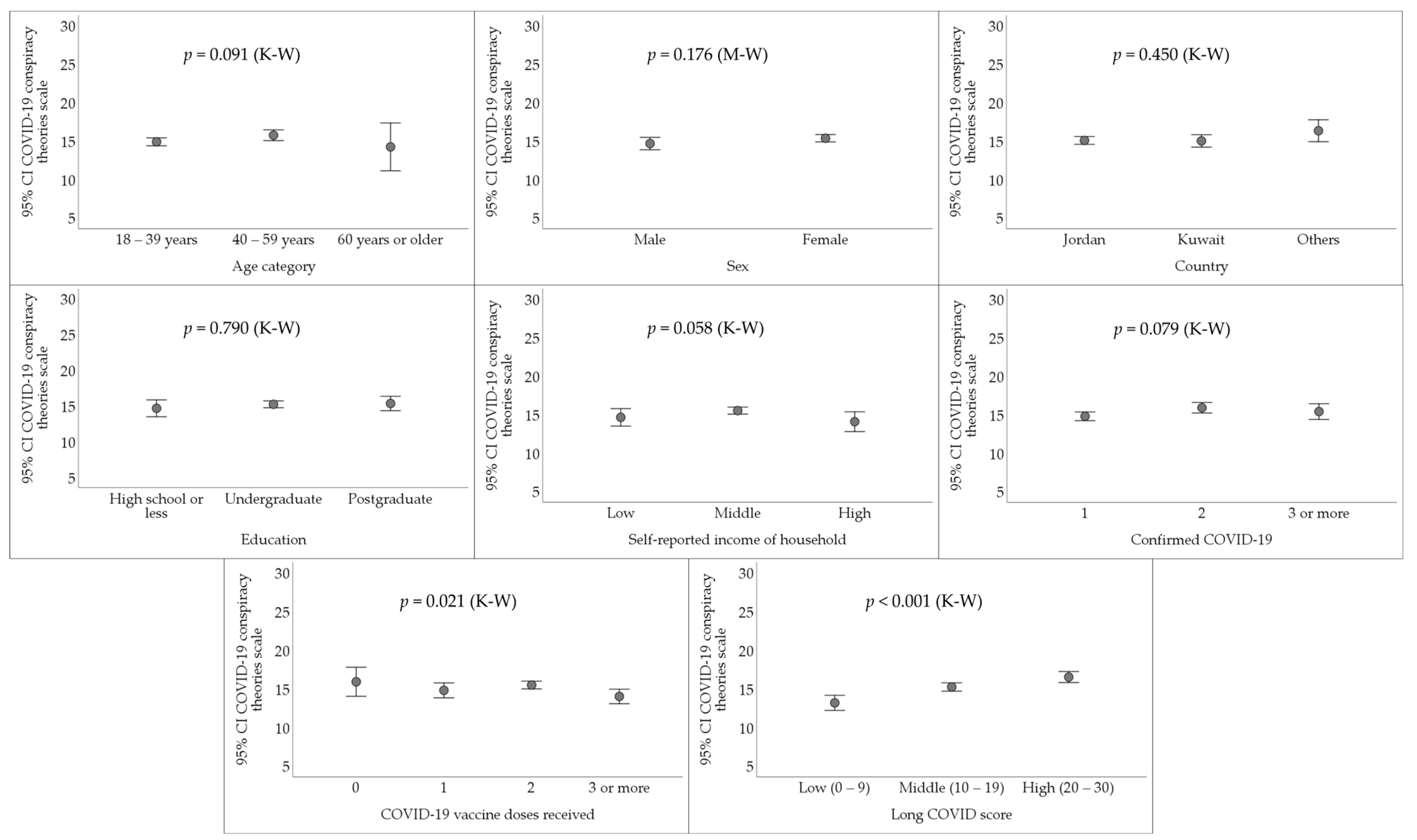

3.4. The Endorsement of COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories among Respondents Who Had Confirmed COVID-19 Diagnosis

3.5. Higher Reporting of Long COVID Manifestations Was Associated with the Endorsement of COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories in Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| aOR | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| COVID | Coronavirus disease |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| K-W | Kruskal-Wallis test |

| M-W | Mann-Whitney U test |

| NPI | Non-pharmaceutical intervention |

| PASC | Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| WHO | The World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 epidemiological update – 17 June 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-epidemiological-update-edition-168 (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Meyerowitz, E.A.; Scott, J.; Richterman, A.; Male, V.; Cevik, M. Clinical course and management of COVID-19 in the era of widespread population immunity. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2024, 22, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, H.; Sharifi, A.; Damanbagh, S.; Nazarnia, H.; Nazarnia, M. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the social sphere and lessons for crisis management: a literature review. Natural Hazards 2023, 117, 2139–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunal, K.; Choudhary, P.; Kumar, J.; Prakash, R.; Singh, A.; Kanchan, K. Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19–A Global Scenario. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, T.; Huang, Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, L. Research progress of post-acute sequelae after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Death & Disease 2024, 15, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, H.C.; Xiao, J.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, G. Long COVID and its Management. Int J Biol Sci 2022, 18, 4768–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jason, L.A.; Hansel, N. Conceptual and Methodological Barriers to Understanding Long COVID. COVID 2024, 4, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuka, J.K.; Nzioki, J.M.; Kelly, J.O.; Musangi, E.N.; Chebungei, L.C.; Nabaweesi, R.; Kiptoo, M.K. Prevalence and Predictors of Long COVID-19 and the Average Time to Diagnosis in the General Population: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. COVID 2024, 4, 968–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanares-Zapatero, D.; Chalon, P.; Kohn, L.; Dauvrin, M.; Detollenaere, J.; Maertens de Noordhout, C.; Primus-de Jong, C.; Cleemput, I.; Van den Heede, K. Pathophysiology and mechanism of long COVID: a comprehensive review. Ann Med 2022, 54, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, S.; Zayachkivska, O.; Hussain, A.; Muller, V. What is really 'Long COVID'? Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, B.; Wills, M.; Sithole, N. Long COVID: what is known and what gaps need to be addressed. Br Med Bull 2023, 147, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziolos, N.R.; Ioannou, P.; Baliou, S.; Kofteridis, D.P. Long COVID-19 Pathophysiology: What Do We Know So Far? Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, L.; Capotescu, C.; Eyal, G.; Finestone, G. Long covid and medical gaslighting: Dismissal, delayed diagnosis, and deferred treatment. SSM Qual Res Health 2022, 2, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, A.D.; Butler-Cole, B.F.; Tazare, J.; Tomlinson, L.A.; Marks, M.; Jit, M.; Briggs, A.; Lin, L.Y.; Carlile, O.; Bates, C.; et al. Clinical coding of long COVID in primary care 2020-2023 in a cohort of 19 million adults: an OpenSAFELY analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 72, 102638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaweethai, T.; Jolley, S.E.; Karlson, E.W.; Levitan, E.B.; Levy, B.; McComsey, G.A.; McCorkell, L.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Parthasarathy, S.; Singh, U.; et al. Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Jama 2023, 329, 1934–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danesh, V.; Arroliga, A.C.; Bourgeois, J.A.; Boehm, L.M.; McNeal, M.J.; Widmer, A.J.; McNeal, T.M.; Kesler, S.R. Symptom Clusters Seen in Adult COVID-19 Recovery Clinic Care Seekers. J Gen Intern Med 2023, 38, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re'em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Gu, X.; Kang, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet 2023, 401, e21–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, A.V.; Jayadevan, R.; Sashidharan, S. Long COVID: An overview. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2021, 15, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajani Mir, M. Brain Fog: a Narrative Review of the Most Common Mysterious Cognitive Disorder in COVID-19. Mol Neurobiol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, A.; Tagliaferro, A.; Balbi, F.; Bordo, A.; Bernardi, S.; Berta, G.; Trucco, L.; Perretta, E.; Gualco, E.; Zoccali, P.; et al. Screening of a Small Number of Italian COVID-19 Syndrome Survivors by Means of the Fatigue Assessment Scale: Long COVID Prevalence and the Role of Gender. COVID 2021, 1, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Michalopoulos, C.; Carpe, S.; Congrete, S.; Shahzad, H.; Reardon, J.; Wakefield, D.; Swart, C.; ZuWallack, R. Post-COVID-19 Condition and Health Status. COVID 2022, 2, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchian, M.-L.; Demeure, F.; Higny, J.; Berners, Y.; Henry, J.; Guedes, A.; Laurence, G.; Saidane, L.; Höcher, A.; Roosens, B.; et al. Three Years of COVID-19 Pandemic—Is the Heart Skipping a Beat? COVID 2023, 3, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tana, C.; Bentivegna, E.; Cho, S.J.; Harriott, A.M.; García-Azorín, D.; Labastida-Ramirez, A.; Ornello, R.; Raffaelli, B.; Beltrán, E.R.; Ruscheweyh, R.; et al. Long COVID headache. J Headache Pain 2022, 23, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zeng, N.; Liu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, S.; Ni, S.; Gong, Y.; et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and management of long COVID: an update. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 28, 4056–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID). Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Soriano, J.B.; Murthy, S.; Marshall, J.C.; Relan, P.; Diaz, J.V. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffrey, K.; Woolford, L.; Maini, R.; Basetti, S.; Batchelor, A.; Weatherill, D.; White, C.; Hammersley, V.; Millington, T.; Macdonald, C.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors for long COVID among adults in Scotland using electronic health records: a national, retrospective, observational cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 71, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, M.J.; Gonakoti, S.; Shariff, R.; Corpuz, C.; Acosta, R.A.H.; Chang, H.; Asemota, I.; Gobbi, E.; Rezai, K. Prevalence and Characteristics of Long COVID 7-12 Months After Hospitalization Among Patients From an Urban Safety-Net Hospital: A Pilot Study. AJPM Focus 2023, 2, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerne, K.; Filion, K.B.; Grad, R.; Ernst, P.; Gershon, A.S.; Eisenberg, M.J. Epidemiological and clinical perspectives of long COVID syndrome. Am J Med Open 2023, 9, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlis, R.H.; Santillana, M.; Ognyanova, K.; Safarpour, A.; Lunz Trujillo, K.; Simonson, M.D.; Green, J.; Quintana, A.; Druckman, J.; Baum, M.A.; et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Long COVID Symptoms Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2238804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangnin, R.; Ritruangroj, W.; Kittisupkajorn, S.; Sukeiam, P.; Inchai, J.; Maneeton, B.; Maneetorn, N.; Chaiard, J.; Theerakittikul, T. Long-COVID Prevalence and Its Association with Health Outcomes in the Post-Vaccine and Antiviral-Availability Era. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, C.E.; Lowe, D.J.; McAuley, A.; Mills, N.L.; Winter, A.J.; Black, C.; Scott, J.T.; O’Donnell, C.A.; Blane, D.N.; Browne, S.; et al. True prevalence of long-COVID in a nationwide, population cohort study. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 7892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, N.D.; Agedew, A.; Dalton, A.F.; Singleton, J.; Perrine, C.G.; Saydah, S. Notes from the Field: Long COVID Prevalence Among Adults - United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024, 73, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, E. US Survey: About 7% of Adults, 1% of Children Have Had Long COVID. Jama 2023, 330, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkodaymi, M.S.; Omrani, O.A.; Fawzy, N.A.; Shaar, B.A.; Almamlouk, R.; Riaz, M.; Obeidat, M.; Obeidat, Y.; Gerberi, D.; Taha, R.M.; et al. Prevalence of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome symptoms at different follow-up periods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022, 28, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Notarte, K.I.; Macasaet, R.; Velasco, J.V.; Catahay, J.A.; Ver, A.T.; Chung, W.; Valera-Calero, J.A.; Navarro-Santana, M. Persistence of post-COVID symptoms in the general population two years after SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2024, 88, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Torres-Macho, J.; Macasaet, R.; Velasco, J.V.; Ver, A.T.; Culasino Carandang, T.H.D.; Guerrero, J.J.; Franco-Moreno, A.; Chung, W.; Notarte, K.I. Presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in COVID-19 survivors with post-COVID symptoms: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Chem Lab Med 2024, 62, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, K.H.; Bao, Y.; Chen, S.; Bednarczyk, R.A.; Vasudevan, L.; Corlin, L. Prior COVID-19 Diagnosis, Severe Outcomes, and Long COVID among U.S. Adults, 2022. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsampasian, V.; Elghazaly, H.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Debski, M.; Naing, T.K.P.; Garg, P.; Clark, A.; Ntatsaki, E.; Vassiliou, V.S. Risk Factors Associated With Post-COVID-19 Condition: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2023, 183, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcaterra, V.; Zanelli, S.; Foppiani, A.; Verduci, E.; Benatti, B.; Bollina, R.; Bombaci, F.; Brucato, A.; Cammarata, S.; Calabrò, E.; et al. Long COVID in Children, Adults, and Vulnerable Populations: A Comprehensive Overview for an Integrated Approach. Diseases 2024, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Raveendran, A.V.; Giordano, R.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Long COVID or Post-COVID-19 Condition: Past, Present and Future Research Directions. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Nirantharakumar, K.; Hughes, S.; Myles, P.; Williams, T.; Gokhale, K.M.; Taverner, T.; Chandan, J.S.; Brown, K.; Simms-Williams, N.; et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat Med 2022, 28, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, E.; Simas, C.; Larson, H.J. An epidemic of uncertainty: rumors, conspiracy theories and vaccine hesitancy. Nature Medicine 2022, 28, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, K.H. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Social Science & Medicine 2020, 263, 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabkowski, P.; Domaradzki, J.; Baranowski, M. Exploring COVID-19 conspiracy theories: education, religiosity, trust in scientists, and political orientation in 26 European countries. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 18116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Mulukom, V.; Pummerer, L.J.; Alper, S.; Bai, H.; Čavojová, V.; Farias, J.; Kay, C.S.; Lazarevic, L.B.; Lobato, E.J.C.; Marinthe, G.; et al. Antecedents and consequences of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2022, 301, 114912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotakis, E.A.; Simou, E. Belief in COVID-19 related conspiracy theories around the globe: A systematic review. Health Policy 2023, 137, 104903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Waite, F.; Rosebrock, L.; Petit, A.; Causier, C.; East, A.; Jenner, L.; Teale, A.-L.; Carr, L.; Mulhall, S.; et al. Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychological Medicine 2022, 52, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Waite, F.; Larkin, M.; Lambe, S.; McShane, H.; Pollard, A.J.; Freeman, D. “It seems impossible that it’s been made so quickly”: a qualitative investigation of concerns about the speed of COVID-19 vaccine development and how these may be overcome. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2022, 18, 2004808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.P.; Efstratiou, A.; Komer, S.R.; Baxter, L.A.; Vasiljevic, M.; Leite, A.C. The impact of risk perceptions and belief in conspiracy theories on COVID-19 pandemic-related behaviours. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0263716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinazo-Calatayud, D.; Agut-Nieto, S.; Arahuete, L.; Peris, R.; Barros, A.; Vázquez-Rodríguez, C. The strength of conspiracy beliefs versus scientific information: the case of COVID 19 preventive behaviours. Frontiers in Psychology 2024, 15, 1325600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coninck, D.; Frissen, T.; Matthijs, K.; d’Haenens, L.; Lits, G.; Champagne-Poirier, O.; Carignan, M.-E.; David, M.D.; Pignard-Cheynel, N.; Salerno, S.; et al. Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories and Misinformation About COVID-19: Comparative Perspectives on the Role of Anxiety, Depression and Exposure to and Trust in Information Sources. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 646394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Campos, C.; Marinho, B.; Rocha, S.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Barbosa Rocha, N. What drives beliefs in COVID-19 conspiracy theories? The role of psychotic-like experiences and confinement-related factors. Soc Sci Med 2022, 292, 114611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Gay Juárez, F.; Khayyat, L.; Ronca, M.; Gold, I. Viral Belief: The Psychology of COVID Conspiracy Theories. 2024; pp. 53-79. [CrossRef]

- van Prooijen, J.W.; Douglas, K.M. Belief in conspiracy theories: Basic principles of an emerging research domain. Eur J Soc Psychol 2018, 48, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, T.K.; Marshall, M.; Stocks, T.V.A.; McKay, R.; Bennett, K.; Butter, S.; Gibson Miller, J.; Hyland, P.; Levita, L.; Martinez, A.P.; et al. Different Conspiracy Theories Have Different Psychological and Social Determinants: Comparison of Three Theories About the Origins of the COVID-19 Virus in a Representative Sample of the UK Population. Frontiers in Political Science 2021, 3, 642510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, M.S. SARS-CoV-2, Covid-19, and the debunking of conspiracy theories. Rev Med Virol 2021, 31, e2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, K.M. COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2021, 24, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsamakis, K.; Tsiptsios, D.; Stubbs, B.; Ma, R.; Romano, E.; Mueller, C.; Ahmad, A.; Triantafyllis, A.S.; Tsitsas, G.; Dragioti, E. Summarising data and factors associated with COVID-19 related conspiracy theories in the first year of the pandemic: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Psychol 2022, 10, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, R.; Lamberty, P. A Bioweapon or a Hoax? The Link Between Distinct Conspiracy Beliefs About the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak and Pandemic Behavior. Social Psychological and Personality Science 2020, 11, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Kamal, A.M.; Kabir, A.; Southern, D.L.; Khan, S.H.; Hasan, S.M.M.; Sarkar, T.; Sharmin, S.; Das, S.; Roy, T.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine rumors and conspiracy theories: The need for cognitive inoculation against misinformation to improve vaccine adherence. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0251605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanchich, M.; Sirota, M.; Jolles, D.; Whiley, L.A. Are COVID-19 conspiracies a threat to public health? Psychological characteristics and health protective behaviours of believers. Eur J Soc Psychol 2021, 51, 969–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierwiaczonek, K.; Gundersen, A.B.; Kunst, J.R. The role of conspiracy beliefs for COVID-19 health responses: A meta-analysis. Curr Opin Psychol 2022, 46, 101346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, E.L.; Ribeiro, C.J.; Santos, G.R.; Almeida, V.S.; Carvalho, H.E.; Schneider, G.; Vieira, L.G.; Alvim, A.L.; Pimenta, F.G.; Carneiro, L.M.; et al. Belief in Conspiracy Theories about COVID-19 Vaccines among Brazilians: A National Cross-Sectional Study. COVID 2024, 4, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Kareem, N.; Alkurtas, M. The negative impact of misinformation and vaccine conspiracy on COVID-19 vaccine uptake and attitudes among the general public in Iraq. Prev Med Rep 2024, 43, 102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsanafi, M.; Salim, N.A.; Sallam, M. Willingness to get HPV vaccination among female university students in Kuwait and its relation to vaccine conspiracy beliefs. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2023, 19, 2194772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Ghazy, R.M.; Al-Salahat, K.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; AlHadidi, N.M.; Eid, H.; Kareem, N.; Al-Ajlouni, E.; Batarseh, R.; Ababneh, N.A.; et al. The Role of Psychological Factors and Vaccine Conspiracy Beliefs in Influenza Vaccine Hesitancy and Uptake among Jordanian Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsanafi, M.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Sallam, M. Monkeypox Knowledge and Confidence in Diagnosis and Management with Evaluation of Emerging Virus Infection Conspiracies among Health Professionals in Kuwait. Pathogens 2022, 11, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Dababseh, D.; Eid, H.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Al-Haidar, A.; Taim, D.; Yaseen, A.; Ababneh, N.A.; Bakri, F.G.; Mahafzah, A. High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagliardi, L. The role of cognitive biases in conspiracy beliefs: A literature review. Journal of Economic Surveys 2023, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.M.; Sutton, R.M.; Callan, M.J.; Dawtry, R.J.; Harvey, A.J. Someone is pulling the strings: hypersensitive agency detection and belief in conspiracy theories. Thinking & Reasoning 2016, 22, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.M.; Sutton, R.M.; Cichocka, A. The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2017, 26, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, W.; Albarracín, D.; Eagly, A.H.; Brechan, I.; Lindberg, M.J.; Merrill, L. Feeling validated versus being correct: a meta-analysis of selective exposure to information. Psychol Bull 2009, 135, 555–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaanders, P.; Sepulveda, P.; Folke, T.; Ortoleva, P.; De Martino, B. Humans actively sample evidence to support prior beliefs. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kindred, R.; Bates, G.W. The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnahan, N.D.; Carter, M.M.; Sbrocco, T. Intolerance of Uncertainty, Looming Cognitive Style, and Avoidant Coping as Predictors of Anxiety and Depression During COVID-19: a Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy 2022, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehri, S.; Sallam, M. Vaccine conspiracy association with higher COVID-19 vaccination side effects and negative attitude towards booster COVID-19, influenza and monkeypox vaccines: A pilot study in Saudi Universities. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2023, 19, 2275962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M.; Abbasi, H.; Obeidat, R.J.; Badayneh, R.; Alkhashman, F.; Obeidat, A.; Oudeh, D.; Uqba, Z.; Mahafzah, A. Unraveling the association between vaccine attitude, vaccine conspiracies and self-reported side effects following COVID-19 vaccination among nurses and physicians in Jordan. Vaccine X 2023, 15, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaberi, M.A.; Al-Sharafi, M.A.; Uzir, M.U.H.; Sabah, A.; Ali, A.M.; Lee, K.H.; Alsalahi, A.; Noman, S.; Lin, C.Y. Psychological Toll of the COVID-19 Pandemic: An In-Depth Exploration of Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia and the Influence of Quarantine Measures on Daily Life. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafini, G.; Parmigiani, B.; Amerio, A.; Aguglia, A.; Sher, L.; Amore, M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. Qjm 2020, 113, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikebaier, S. COVID-19, new challenges to human safety: a global review. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1371238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidkova, R.; Malinakova, K.; van Dijk, J.P.; Tavel, P. The Coronavirus Pandemic and the Occurrence of Psychosomatic Symptoms: Are They Related? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaseth, K.; Grande, R.B.; Leiknes, K.A.; Benth, J.; Lundqvist, C.; Russell, M.B. Personality traits and psychological distress in persons with chronic tension-type headache. The Akershus study of chronic headache. Acta Neurol Scand 2011, 124, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, E.C. Myofascial pain--an overview. Ann Acad Med Singap 2007, 36, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemogne, C.; Gouraud, C.; Pitron, V.; Ranque, B. Why the hypothesis of psychological mechanisms in long COVID is worth considering. J Psychosom Res 2023, 165, 111135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leibovitz, T.; Shamblaw, A.L.; Rumas, R.; Best, M.W. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: Relations with anxiety, quality of life, and schemas. Pers Individ Dif 2021, 175, 110704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Eaton, L.A.; Kalichman, S.C.; Brousseau, N.M.; Hill, E.C.; Fox, A.B. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Transl Behav Med 2020, 10, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simione, L.; Vagni, M.; Gnagnarella, C.; Bersani, G.; Pajardi, D. Mistrust and Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories Differently Mediate the Effects of Psychological Factors on Propensity for COVID-19 Vaccine. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 683684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolley, D.; Marques, M.D.; Cookson, D. Shining a spotlight on the dangerous consequences of conspiracy theories. Curr Opin Psychol 2022, 47, 101363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Prooijen, J.W.; Etienne, T.W.; Kutiyski, Y.; Krouwel, A.P.M. Conspiracy beliefs prospectively predict health behavior and well-being during a pandemic. Psychol Med 2023, 53, 2514–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tselebis, A.; Sikaras, C.; Milionis, C.; Sideri, E.P.; Fytsilis, K.; Papageorgiou, S.M.; Ilias, I.; Pachi, A. A Moderated Mediation Model of the Influence of Cynical Distrust, Medical Mistrust, and Anger on Vaccination Hesitancy in Nursing Staff. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ 2023, 13, 2373–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogart, L.M.; Ojikutu, B.O.; Tyagi, K.; Klein, D.J.; Mutchler, M.G.; Dong, L.; Lawrence, S.J.; Thomas, D.R.; Kellman, S. COVID-19 Related Medical Mistrust, Health Impacts, and Potential Vaccine Hesitancy Among Black Americans Living With HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2021, 86, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivetti, M.; Paleari, F.-G.; Ertan, I.; Di Battista, S.; Ulukök, E. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and vaccinations: A conceptual replication study in Turkey. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology 2023, 17, 18344909231170097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.D.; Fu, Q.; Shrestha, S.; Nguyen, K.H.; Stopka, T.J.; Cuevas, A.; Corlin, L. Medical mistrust, discrimination, and COVID-19 vaccine behaviors among a national sample U.S. adults. SSM Popul Health 2022, 20, 101278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrieri, V.; Guthmuller, S.; Wübker, A. Trust and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 9245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regazzi, L.; Lontano, A.; Cadeddu, C.; Di Padova, P.; Rosano, A. Conspiracy beliefs, COVID-19 vaccine uptake and adherence to public health interventions during the pandemic in Europe. European Journal of Public Health 2023, 33, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, N.; Delfabbro, P.; Balzan, R. COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs and their relationship with perceived stress and pre-existing conspiracy beliefs. Pers Individ Dif 2020, 166, 110201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro-López-Menchero, P.; Martín-Sanz, M.B.; Fernandez-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Gómez-Sanchez, S.M.; Gil-Crujera, A.; Ceballos-García, L.; Escribano-Mediavilla, N.I.; Fuentes-Fuentes, M.V.; Palacios-Ceña, D. Living and Coping with Olfactory and Taste Disorders: A Qualitative Study of People with Long-COVID-19. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Guijarro, C.; Velasco-Arribas, M.; Torres-Macho, J.; Franco-Moreno, A.; Truini, A.; Pellicer-Valero, O.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Neuropathic post-COVID pain symptomatology is not associated with serological biomarkers at hospital admission and hospitalization treatment in COVID-19 survivors. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1301970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Ryan-Murua, P.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, J.; Palacios-Ceña, M.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Torres-Macho, J. Serological Biomarkers at Hospital Admission Are Not Related to Long-Term Post-COVID Fatigue and Dyspnea in COVID-19 Survivors. Respiration 2022, 101, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias-Guiu, J.A.; Delgado-Alonso, C.; Díez-Cirarda, M.; Martínez-Petit, Á.; Oliver-Mas, S.; Delgado-Álvarez, A.; Cuevas, C.; Valles-Salgado, M.; Gil, M.J.; Yus, M.; et al. Neuropsychological Predictors of Fatigue in Post-COVID Syndrome. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalbandian, A.; Sehgal, K.; Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; McGroder, C.; Stevens, J.S.; Cook, J.R.; Nordvig, A.S.; Shalev, D.; Sehrawat, T.S.; et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nature Medicine 2021, 27, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, J.; Bilasy, S.E.; Yang, C.; El-Shamy, A. Exploring the Complexities of Long COVID. Viruses 2024, 16, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Dababseh, D.; Yaseen, A.; Al-Haidar, A.; Taim, D.; Eid, H.; Ababneh, N.A.; Bakri, F.G.; Mahafzah, A. COVID-19 misinformation: Mere harmless delusions or much more? A knowledge and attitude cross-sectional study among the general public residing in Jordan. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0243264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, J.M.; Markey, J.C.; Ebert-May, D. The Other Half of the Story: Effect Size Analysis in Quantitative Research. CBE—Life Sciences Education 2013, 12, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Torres-Macho, J.; Ruiz-Ruigómez, M.; Arrieta-Ortubay, E.; Rodríguez-Rebollo, C.; Akasbi-Moltalvo, M.; Pardo-Guimerá, V.; Ryan-Murua, P.; Lumbreras-Bermejo, C.; Pellicer-Valero, O.J.; et al. Presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in COVID-19 survivors with post-COVID symptoms 2 years after hospitalization: The VIPER study. J Med Virol 2024, 96, e29676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Pellicer-Valero, O.J.; Martín-Guerrero, J.D.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Investigating the fluctuating nature of post-COVID pain symptoms in previously hospitalized COVID-19 survivors: the LONG-COVID-EXP multicenter study. PAIN Reports 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evcik, D. Musculoskeletal involvement: COVID-19 and post COVID 19. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil 2023, 69, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, R.S.; Nieters, A.; Kräusslich, H.G.; Brockmann, S.O.; Göpel, S.; Kindle, G.; Merle, U.; Steinacker, J.M.; Rothenbacher, D.; Kern, W.V. Post-acute sequelae of covid-19 six to 12 months after infection: population based study. Bmj 2022, 379, e071050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diar Bakerly, N.; Smith, N.; Darbyshire, J.L.; Kwon, J.; Bullock, E.; Baley, S.; Sivan, M.; Delaney, B. Pathophysiological Mechanisms in Long COVID: A Mixed Method Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, T.; Huang, Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, L. Research progress of post-acute sequelae after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, K.M.; Sutton, R.M.; Cichocka, A. The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2017, 26, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.-y.; Chan, H.-W.; Douglas, K.M. Conspiracy Theories about Infectious Diseases: An Introduction. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology 2021, 15, 18344909211057657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Haim, Y.; Lamy, D.; Pergamin, L.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; van, I.M.H. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychol Bull 2007, 133, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkovskis, P.; Warwick, H.; Deale, A. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for Severe and Persistent Health Anxiety (Hypochondriasis). Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 2003, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderman, N.; Ironson, G.; Siegel, S.D. Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2005, 1, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.C.; Chen, S.J.; Zhong, B.L. Sense of Alienation and Its Associations With Depressive Symptoms and Poor Sleep Quality in Older Adults Who Experienced the Lockdown in Wuhan, China, During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2022, 35, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Creed, F.H.; Ma, Y.L.; Leung, C.M. Somatic symptom burden and health anxiety in the population and their correlates. J Psychosom Res 2015, 78, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, G.; Starcevic, V.; Scalone, A.; Cavallo, J.; Musetti, A.; Schimmenti, A. The Doctor Is In(ternet): The Mediating Role of Health Anxiety in the Relationship between Somatic Symptoms and Cyberchondria. J Pers Med 2022, 12, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gay Juárez, F.; Solomonova, E.; Nephtali, E.; Gold, I. Conspiracies and contagion: Two patterns of COVID-19 related beliefs associated with distinct mental symptomatology. Psychiatry Research Communications 2024, 4, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorna, R.; MacDermott, N.; Rayner, C.; O'Hara, M.; Evans, S.; Agyen, L.; Nutland, W.; Rogers, N.; Hastie, C. Long COVID guidelines need to reflect lived experience. Lancet 2021, 397, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora-Romo, J. Health psychology on long COVID: Strategies based on NICE and WHO guidelines recommendations. Salud mental 2022, 45, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmer, T.; Borzikowsky, C.; Lieb, W.; Horn, A.; Krist, L.; Fricke, J.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Rabe, K.F.; Maetzler, W.; Maetzler, C.; et al. Severity, predictors and clinical correlates of Post-COVID syndrome (PCS) in Germany: A prospective, multi-centre, population-based cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 51, 101549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelmann, P.; Löwe, B.; Brehm, T.T.; Weigel, A.; Ullrich, F.; Addo, M.M.; Schulze Zur Wiesch, J.; Lohse, A.W.; Toussaint, A. Risk factors for worsening of somatic symptom burden in a prospective cohort during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 1022203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouraud, C.; Bottemanne, H.; Lahlou-Laforêt, K.; Blanchard, A.; Günther, S.; Batti, S.E.; Auclin, E.; Limosin, F.; Hulot, J.S.; Lebeaux, D.; et al. Association Between Psychological Distress, Cognitive Complaints, and Neuropsychological Status After a Severe COVID-19 Episode: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 725861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.N.; Ling, M.; Kerr, J.R.; Hill, S.R.; Marques, M.D.; Mawson, H.; Clarke, E.J.R. People do change their beliefs about conspiracy theories—but not often. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsky, A.J.; Peekna, H.M.; Borus, J.F. Somatic symptom reporting in women and men. J Gen Intern Med 2001, 16, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillingim, R.B. Sex, gender, and pain: women and men really are different. Curr Rev Pain 2000, 4, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M.; Prime, H.; Johnson, D.; May, S.S.; Jenkins, J.M.; Browne, D.T. The disparate impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of female and male caregivers. Soc Sci Med 2021, 275, 113801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, R.S.; Ayers, B.L.; Rowland, B.; Moore, R.; Hallgren, E.; McElfish, P.A. "Life is hard": How the COVID-19 pandemic affected daily stressors of women. Dialogues Health 2022, 1, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, C.E.; Lowe, D.J.; McAuley, A.; Winter, A.J.; Mills, N.L.; Black, C.; Scott, J.T.; O'Donnell, C.A.; Blane, D.N.; Browne, S.; et al. Outcomes among confirmed cases and a matched comparison group in the Long-COVID in Scotland study. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneller, M.C.; Liang, C.J.; Marques, A.R.; Chung, J.Y.; Shanbhag, S.M.; Fontana, J.R.; Raza, H.; Okeke, O.; Dewar, R.L.; Higgins, B.P.; et al. A Longitudinal Study of COVID-19 Sequelae and Immunity: Baseline Findings. Ann Intern Med 2022, 175, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.; van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. An intersectional analysis of long COVID prevalence. Int J Equity Health 2023, 22, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbesen, B.D.; Giordano, R.; Hedegaard, J.N.; Calero, J.A.V.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Rasmussen, B.S.; Nielsen, H.; Schiøttz-Christensen, B.; Petersen, P.L.; Castaldo, M.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Multitype Post-COVID Pain in a Cohort of Previously Hospitalized COVID-19 Survivors: A Danish Cross-Sectional Survey. The Journal of Pain. [CrossRef]

- Boufidou, F.; Medić, S.; Lampropoulou, V.; Siafakas, N.; Tsakris, A.; Anastassopoulou, C. SARS-CoV-2 Reinfections and Long COVID in the Post-Omicron Phase of the Pandemic. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 12962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Català, M.; Mercadé-Besora, N.; Kolde, R.; Trinh, N.T.H.; Roel, E.; Burn, E.; Rathod-Mistry, T.; Kostka, K.; Man, W.Y.; Delmestri, A.; et al. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines to prevent long COVID symptoms: staggered cohort study of data from the UK, Spain, and Estonia. Lancet Respir Med 2024, 12, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannock, M.D.; Chew, R.F.; Preiss, A.J.; Hadley, E.C.; Redfield, S.; McMurry, J.A.; Leese, P.J.; Girvin, A.T.; Crosskey, M.; Zhou, A.G.; et al. Long COVID risk and pre-COVID vaccination in an EHR-based cohort study from the RECOVER program. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, S.A.; Pollett, S.D.; Fries, A.C.; Berjohn, C.M.; Maves, R.C.; Lalani, T.; Smith, A.G.; Mody, R.M.; Ganesan, A.; Colombo, R.E.; et al. Persistent COVID-19 Symptoms at 6 Months After Onset and the Role of Vaccination Before or After SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2251360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Count (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age category | 18 – 39 years | 460 (60.9) |

| 40 – 59 years | 263 (34.8) | |

| 60 years or older | 32 (4.2) | |

| Sex | Male | 222 (29.4) |

| Female | 533 (70.6) | |

| Country | Jordan | 438 (58.0) |

| Kuwait | 245 (32.5) | |

| Others 2 | 72 (9.5) | |

| Education | High school or less | 163 (21.6) |

| Undergraduate | 464 (61.5) | |

| Postgraduate | 128 (17.0) | |

| Self-reported income of household | Low | 139 (18.4) |

| Middle | 512 (67.8) | |

| High | 104 (13.8) | |

| Self-reported history of chronic disease | Yes | 193 (25.6) |

| No | 562 (74.4) | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Underweight | 14 (1.9) |

| Healthy weight | 272 (36.0) | |

| Overweight | 255 (33.8) | |

| Obesity | 214 (28.3) | |

| Smoking | Non-smoker | 496 (65.7) |

| Ex-smoker | 58 (7.7) | |

| Current smoker | 201 (26.6) | |

| Confirmed COVID-19 1 | 0 | 262 (34.7) |

| 1 | 297 (39.3) | |

| 2 | 125 (16.6) | |

| 3 or more | 71 (9.4) | |

| Hospitalized due to COVID-19 | Yes | 39 (7.9) |

| No | 454 (92.1) | |

| COVID-19 vaccine doses received | 0 | 30 (6.1) |

| 1 | 28 (5.7) | |

| 2 | 329 (66.7) | |

| 3 or more | 106 (21.5) |

| Variable | Category | LongCOVID score | p value, χ2 | ||

| Low (0 – 9) | Middle (10 – 19) | High (20 – 30) | |||

| Count (%) | Count (%) | Count (%) | |||

| Age category | 18 – 39 years | 64 (20.8) | 143 (46.4) | 101 (32.8) | 0.026, 11.047 |

| 40 – 59 years | 38 (22.5) | 89 (52.7) | 42 (24.9) | ||

| 60 years or older | 8 (50.0) | 6 (37.5) | 2 (12.5) | ||

| Sex | Male | 49 (35.8) | 66 (48.2) | 22 (16.1) | <0.001, 26.894 |

| Female | 61 (17.1) | 172 (48.3) | 123 (34.6) | ||

| Country | Jordan | 62 (20.5) | 154 (50.8) | 87 (28.7) | 0.216, 5.786 |

| Kuwait | 38 (25.9) | 60 (40.8) | 49 (33.3) | ||

| Others 2 | 10 (23.3) | 24 (55.8) | 9 (20.9) | ||

| Education | High school or less | 21 (24.7) | 39 (45.9) | 25 (29.4) | 0.724, 2.064 |

| Undergraduate | 67 (21.4) | 158 (50.5) | 88 (28.1) | ||

| Postgraduate | 22 (23.2) | 41 (43.2) | 32 (33.7) | ||

| Self-reported income of household | Low | 12 (15.0) | 42 (52.5) | 26 (32.5) | <0.001, 23.387 |

| Middle | 67 (19.6) | 174 (50.9) | 101 (29.5) | ||

| High | 31 (43.7) | 22 (31.0) | 18 (25.4) | ||

| Self-reported history of chronic disease | Yes | 24 (18.6) | 58 (45.0) | 47 (36.4) | 0.111, 4.403 |

| No | 86 (23.6) | 180 (49.5) | 98 (26.9) | ||

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Underweight | 3 (37.5) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (37.5) | 0.123, 10.033 |

| Healthy weight | 46 (25.7) | 92 (51.4) | 41 (22.9) | ||

| Overweight | 31 (19.6) | 80 (50.6) | 47 (29.7) | ||

| Obesity | 30 (20.3) | 64 (43.2) | 54 (36.5) | ||

| Smoking | Non-smoker | 72 (21.6) | 157 (47.0) | 105 (31.4) | 0.558, 3.000 |

| Ex-smoker | 7 (18.4) | 20 (52.6) | 11 (28.9) | ||

| Current smoker | 31 (25.6) | 61 (50.4) | 29 (24.0) | ||

| Confirmed COVID-19 | 1 | 91 (30.6) | 141 (47.5) | 65 (21.9) | <0.001, 38.147 |

| 2 | 13 (10.4) | 63 (50.4) | 49 (39.2) | ||

| 3 | 6 (8.5) | 34 (47.9) | 31 (43.7) | ||

| Hospitalized due to COVID-19 | Yes | 5 (12.8) | 17 (43.6) | 17 (43.6) | 0.091, 4.797 |

| No | 105 (23.1) | 221 (48.7) | 128 (28.2) | ||

| COVID-19 vaccine doses received | 0 | 9 (30.0) | 11 (36.7) | 10 (33.3) | 0.256, 7.758 |

| 1 | 4 (14.3) | 14 (50.0) | 10 (35.7) | ||

| 2 | 67 (20.4) | 160 (48.6) | 102 (31.0) | ||

| 3 | 30 (28.3) | 53 (50.0) | 23 (21.7) | ||

| COVID-19 conspiracy score 1 | Low (5 – 11) | 38 (38.8) | 40 (40.8) | 20 (20.4) | <0.001, 34.989 |

| Middle (12 – 18) | 55 (20.1) | 148 (54.2) | 70 (25.6) | ||

| High (19 – 25) | 17 (13.9) | 50 (41.0) | 55 (45.1) | ||

| High long COVID score (20–30) vs. low long COVID score (0–9) | aOR1 (95% CI2) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Factors | ||

| COVID-19 conspiracy theories | ||

| High COVID-19 conspiracies score (19–25) vs. low COVID-19 conspiracies score (5–11) | 6.85 (2.90–16.13) | <0.001 |

| High COVID-19 conspiracies score (19 – 25) vs. middle COVID-19 conspiracies score (12–18) | 3.21 (1.56–6.58) | 0.002 |

| Age | ||

| 18 – 39 years vs. 60 years or older | 3.62 (0.65–20.32) | 0.144 |

| 40 – 59 years vs. 60 years or older | 2.09 (0.36–12.16) | 0.413 |

| Sex | ||

| Female vs. male | 5.15 (2.66–10.00) | <0.001 |

| Self-reported income of household | ||

| Low vs. high | 4.70 (1.65–13.40) | 0.004 |

| Middle vs. high | 2.40 (1.10–5.22) | 0.027 |

| Frequency of COVID-19 confirmed diagnosis | ||

| Three times or more vs. once | 10.31 (3.73–28.57) | <0.001 |

| Three times or more vs. twice | 1.90 (0.60–6.06) | 0.276 |

| History of hospitalization due to COVID-19 | ||

| Yes vs. no | 5.53 (1.66–18.46) | 0.005 |

| Middle long COVID score (10–19) vs. low long COVID score (0–9) | ||

| Factors | ||

| COVID-19 conspiracy theories | ||

| High COVID-19 conspiracies score (19–25) vs. low COVID-19 conspiracies score (5–11) | 2.82 (1.32–6.06) | 0.008 |

| High COVID-19 conspiracies score (19–25) vs. middle COVID-19 conspiracies score (12–18) | 1.23 (0.63–2.42) | 0.538 |

| Age | ||

| 18 – 39 years vs. 60 years or older | 1.80 (0.54–6.04) | 0.340 |

| 40 – 59 years vs. 60 years or older | 1.66 (0.48–5.76) | 0.423 |

| Sex | ||

| Female vs. male | 2.11 (1.26–3.55) | 0.005 |

| Self-reported income of household | ||

| Low vs. high | 5.10 (2.03–12.84) | 0.001 |

| Middle vs. high | 3.12 (1.60–6.06) | 0.001 |

| Frequency of COVID-19 confirmed diagnosis | ||

| Three times or more vs. once | 4.76 (1.81–12.50) | 0.002 |

| Three times or more vs. twice | 1.52 (0.50–4.63) | 0.466 |

| History of hospitalization due to COVID-19 | ||

| Yes vs. no | 2.69 (0.86–8.43) | 0.089 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).