Submitted:

08 August 2024

Posted:

09 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature and Hypothesis Development:

2.1. Independence of the Audit Committee

2.2. Experience of the Audit Committee

2.3. Number of AC Meetings (NACMs)

2.4. The Audit Committee’s Size

2.5. Moderating Effect of Family Control

3. Methodology

3.1. Population and Sample:

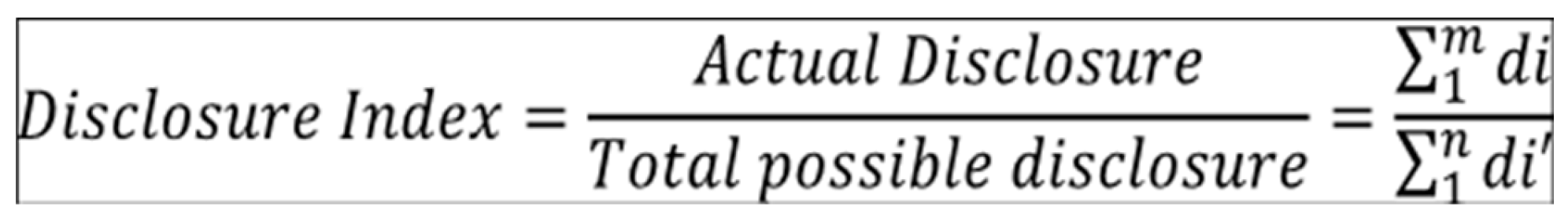

3.2. Measurement of Variables:

3.2. Independent Variable:

| Variable | Measurement | |

| The AC Independence | IND | measured as the percentage of independent audit committee members divided on the total number of audit committee member |

| The AC Experience | EXP | takes the value of 1 if all audit committee members are qualified (holding an undergraduate degree in accounting or finance), and at least one of them has an accounting professional qualification (as specified in the CG code for Jordan), and 0 otherwise |

| Number of AC Meetings | MEET | measured as the number of meetings of the audit committee held during full year |

| Size of the AC | SIZE | audit committee size is measured by the number of audit committee members reported in the firm’s annual financial reports |

| Family Control | FO | measured by the percentage of 5 percent or more of shares held by a family |

4. Result and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

| Variables | Measure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Max | Min | Stdev. | |

| DRISK | 0.566 | 0.793 | 0.172 | 0.122 |

| IND | 0.887 | 1.0 | 0.333 | 0.169 |

| EXP | 1.476 | 8.0 | 0.0 | 1.936 |

| MEET | 7.405 | 19.0 | 4.0 | 2.319 |

| SIZE | 3.953 | 8.0 | 3.0 | 1.221 |

| FO (After first difference) | 13.433 | 59.926 | 0.0 | 16.384 |

| DRISK: Voluntary risk disclosure, IND: Independence of the audit committee, EXP: Experience of the audit committee, MEET: Number of meetings of the audit committee, SIZE: Size of the audit committee, FO: Family ownership | ||||

- The mean of risk disclosure rate in the selected banks for (2017-2023) was (0.566), having the deviation (0.122). Besides, the highest observation recorded (0.793), while the value of the lowest observation was (0.172). The values indicate a difference between the selected banks in disclosing risks, which may be due to the difference in the banks’ internal policies related to disclosure, their difference in size, and their investment in technology and advanced information systems.

- The mean of Independence of the audit committee in the selected banks for (2017-2023) was (0.887), with a deviation of (0.169), and the value of the highest observation was (1.0), while the value of the lowest observation was (0.333). The values indicate a difference between the selected banks in the independence of the audit committee, which may be due to the difference in the size of those banks, size of their board of directors, the organizational structure followed by them, and the shareholders’ orientations in imposing oversight and accountability.

- The mean of experience of the audit committee in the selected banks for (2017-2023) was (1.476), with a deviation of (1.936), and the value of the highest observation was (8.0), while the value of the lowest observation was (0.0). The values indicate a difference between those banks in the experience of the audit committee, which may be due to the difference in the composition of the board of directors, and its inclusion of members who hold certificates, skills, and competencies in the field of accounting and finance.

- The mean of number of meetings held by the audit committee in those banks for the period (2017-2023) was (7.405), recording a deviation of (2.319). Besides, the value of the highest observation during the period was (19.0), while the value of the lowest observation was (4.0). The values indicate that there is a difference in the number of audit committee meetings, which is due to the difference in the size of commercial banks, the level of complexity in their activities and operations, the level and type of risks they deal with, and the difference in the organizational and administrative structure followed in the bank.

- The mean of size of the audit committee in those banks for the period (2017-2023) was (3.953), recording a deviation of (1.221). Furthermore, the highest observation’s value during the said period was (8.0). Contrastingly, the lowest observation’s value was (3.0). The values denote a difference between the selected banks in the size of the audit committee, and this may be due to the difference in the number of board members, the diversity in its activities and operations, the complexity of the financial services provided, and the extent of its commitment to governance standards regarding the size of audit committees.

- The mean of Family ownership in those banks for (2017-2023) was (13.433), recording the deviation (16.384). Besides, the highest observation’s level during the said period was (59.926), while the lowest observation’s level was (0.0). The values indicate a difference between the selected banks in family ownership, and this may be due to the difference in investment strategies in commercial banks and internal policies that encourage family participation.

4.2. Test of Multicollinearity:

| Variable | IND | EXP | MEET | SIZE | FO |

| IND | 1.000 | ||||

| EXP | -0.257** | 1.000 | |||

| MEET | 0.023 | 0.373** | 1.000 | ||

| SIZE | -0.253** | 0.667** | 0.147 | 1.000 | |

| FO | -0.155 | 0.240** | 0.056 | -0.022 | 1.000 |

|

IND: AC Independence, EXP: Experience of the AC, MEET: Number of meetings of the AC, SIZE: Size of the AC, FO: Family ownership. (**) Significant at 0.01 | |||||

| Variable | VIF |

| IND | 1.117 |

| EXP | 2.403 |

| MEET | 1.208 |

| SIZE | 2.008 |

| FO | 1.158 |

| IND: AC Independence, EXP: AC Experience, MEET: Number of meetings of the AC, SIZE: Size of the AC, FO: Family ownership. | |

4.3. Stationary Test:

| Variables | LLC-statistic | Prob. | Results |

| DRISK | -5.283 | 0.000 | Stationary at level |

| IND | -3.265 | 0.020 | Stationary at level |

| EXP | -2.967 | 0.042 | Stationary at level |

| MEET | -4.159 | 0.001 | Stationary at level |

| SIZE | -4.261 | 0.001 | Stationary at level |

| FO (After first difference) | -8.122 | 0.000 | Stationary at level |

| DRISK: Voluntary risk disclosure, IND: AC Independence, EXP: AC Experience, MEET: AC Number of meetings, SIZE: Size of the AC, FO: Family ownership | |||

4.4. Estimate the Model

- Pooled Regression Model (PRM)

- Fixed Effect Model (FEM)

- Random Effect Model (REM)

| Hypothesis | Lagrange Multiplier | Hausman | Appropriate Model | ||

| Chi2 | Sig. | Chi2 | Sig. | ||

| H1 | 101.041 | 0.004 | 3.992 | 0.407 | REM |

| H1-a | 106.071 | 0.001 | 2.190 | 0.139 | REM |

| H1-b | 114.976 | 0.000 | 2.211 | 0.137 | REM |

| H1-c | 105..045 | 0.002 | 0.051 | 0.821 | REM |

| H1-d | 112.082 | 0.000 | 1.971 | 0.160 | REM |

| H2 | 90.183 | 0.026 | 2.922 | 0.967 | REM |

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

| Variable | Co-eff | Std Error | T-value | P-value* | |

| IND | 0.035 | 0.006 | 5.697 | 0.000 | |

| EXP | 0.029 | 0.006 | 5.192 | 0.000 | |

| MEET | 0.006 | 0.005 | 1.168 | 0.246 | |

| SIZE | 0.005 | 0.002 | 2.745 | 0.008 | |

|

R-squared Adjusted R-squared F-statistic Prob*(F-statistic) D-W |

0.384 0.353 12.327 0.000 1.831 |

||||

| Variable | Co-eff | Std Error | T-value | P-value* | |

| IND | 0.007 | 0.014 | 0.480 | 0.633 | |

| EXP | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.944 | 0.348 | |

| MEET | 0.025 | 0.005 | 4.601 | 0.000 | |

| SIZE | 0.003 | 0.015 | 0.177 | 0.860 | |

| FO | 0.007 | 0.002 | 3.448 | 0.001 | |

| IND*FO | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.525 | 0.601 | |

| EXP*FO | 0.001 | 0.003 | 2.091 | 0.040 | |

| MEET*FO | 0.002 | 0.001 | 3.780 | 0.000 | |

| SIZE*FO | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.659 | 0.101 | |

|

R-squared Adjusted R-squared F-statistic Prob*(F-statistic) D-W |

0.388 0.313 5.210 0.000 1.706 |

||||

5. Conclusions

6. Limitation and Future Studies

References

- Adu Gyamfi, B. Public policy making and policy change: Ghana’s local governance, education and health policies in perspective. Public Policy 2023, 2023, 01-05. [CrossRef]

- Al-Najjar, B.; Abed, S. The association between disclosure of forward-looking information and corporate governance mechanisms: Evidence from the UK before the financial crisis period. Managerial Auditing Journal 2014, 29, 578-595. [CrossRef]

- Pacelli, J. Corporate Culture In Financial Markets. 2016.

- Saggar, R.; Singh, B. Corporate governance and risk reporting: Indian evidence. Managerial Auditing Journal 2017, 32, 378-405. [CrossRef]

- Talpur, S.; Lizam, M.; Zabri, S.M. Do audit committee structure increases influence the level of voluntary corporate governance disclosures? Property Management 2018, 36, 544.561-. [CrossRef]

- Saggar, R.; Singh, B. Drivers of corporate risk disclosure in Indian non-financial companies: a longitudinal approach. Management and Labour Studies 2019, 44, 303-325. [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A.; Al-Ajmi, J. The role of audit committee attributes in corporate sustainability reporting: Evidence from banks in the Gulf Cooperation Council. Journal of Applied Accounting Research 2020, 21, 249-264. [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Agency problems and residual claims. The journal of law and Economics 1983, 26, 327-349.

- Lin, J.W.; Hwang, M.I. Audit quality, corporate governance, and earnings management: A meta-analysis. International journal of auditing 2010, 14, 57-77. [CrossRef]

- Alqatamin, R.M. Audit committee effectiveness and company performance: Evidence from Jordan. Accounting and Finance Research 2018, 7, 48. [CrossRef]

- Abdullatif, M.; Ghanayem, H.; Ahmad-Amin, R.; Al-shelleh, S.; Sharaiha, L. The performance of audit committees in Jordanian public listed companies. Corporate Ownership and Control 2015, 13, 762-773.

- Saha, R. Corporate governance, voluntary disclosure and firm valuation relationship: evidence from top listed Indian firms. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 2024, 14, 187-219. [CrossRef]

- Allegrini, M.; Greco, G. Corporate boards, audit committees and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Italian listed companies. Journal of Management & Governance 2013, 1, 187-216. [CrossRef]

- Agyei-Mensah, B.K.; Buertey, S. Do culture and governance structure influence extent of corporate risk disclosure? International Journal of Managerial Finance 2019, 15, 315-334. [CrossRef]

- Elshandidy, T.; Elmassri, M.; Elsayed, M. Integrated reporting, textual risk disclosure and market value. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 2022, 22, 173-193. [CrossRef]

- Neifar, S.; Jarboui, A. Corporate governance and operational risk voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Islamic banks. Research in International Business and Finance 2018, 46, 43-54. [CrossRef]

- Fallan, E.; Fallan, L. Corporate tax behaviour and environmental disclosure: Strategic trade-offs across elements of CSR? Scandinavian Journal of Management 2019, 35, 101042.

- Elshandidy, T.; Shrives, P.J.; Bamber, M.; Abraham, S. Risk reporting: A review of the literature and implications for future research✩. Journal of Accounting Literature 2018, 40, 54-82. [CrossRef]

- Alfraih, M.M. The effectiveness of board of directors’ characteristics in mandatory disclosure compliance. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 2016, 24, 154-176. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, A.; Fattah, T.A. Corporate governance and initial compliance with IFRS in emerging markets: The case of income tax accounting in Egypt. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 2015, 24, 46-60. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Hasija, Y. Identification and screening of BACE1 inhibitors using Drug Repurposing: A Computational Approach. In Proceedings of 2023 3rd International Conference on Innovative Sustainable Computational Technologies (CISCT); pp. 1-5.

- Tsalavoutas, I.; Dionysiou, D. Value relevance of IFRS mandatory disclosure requirements. Journal of Applied Accounting Research 2014, 15, 22-42. [CrossRef]

- Al-Attar, K. The effect of accounting information system on corporate governance. Accounting 2021, 7, 99-110. [CrossRef]

- Khoshbakht, N.; Habibi, M.; Ghadiri, M. THE STUDY OF LAWS AND REGULATION ON LIFESTYLE (PRIVACY, SOCIAL SECURITY AND EMPLIOYMENT STATUS) IN HIV/AIDS PATIENTS. Revista Turismo Estudos e Práticas-RTEP/UERN 2019, 1-12.

- Al Sawalqa, F.A.; Al-Msiedeen, J. Importance and potential advantages of web-based corporate disclosure in Jordan: current status and future aspirations. Business and Management Horizons 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Tapanjeh, A.M. Corporate governance from the Islamic perspective: A comparative analysis with OECD principles. Critical Perspectives on accounting 2009, 20, 55.6-567. [CrossRef]

- Khorma, T. The myth of the Jordanian monarchy’s resilience to the Arab Spring: lack of genuine political reform undermines social base of monarchy. 2014.

- Al-Lozi, A.; Nielsen, S.S.; Hershey, T.; Birke, A.; Checkoway, H.; Criswell, S.R.; Racette, B.A. Cognitive control dysfunction in workers exposed to manganese-containing welding fume. American journal of industrial medicine 2017, 60, 181-188. [CrossRef]

- Hussainey, K.; Tahat, Y.; Aladwan, M. The impact of corporate governance on risk disclosure: Jordanian evidence. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal 2019, 23.

- Makhlouf, M.H.; Laili, N.H.; Ramli, N.A.; Al-Sufy, F.; Basah, M.Y. Board of directors, firm performance and the moderating role of family control in Jordan. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal 2018, 22, 1-15.

- Alkurdi, A.; Hussainey, K.; Tahat, Y.; Aladwan, M. The impact of corporate governance on risk disclosure: Jordanian evidence. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal 2019, 23, 1-16.

- Alhosban, A.A.; Al-Sharairi, M. Role of internal auditor in dealing with computer networks technology-Applied study in Islamic banks in Jordan. International Business Research 2017, 10, 259-269. [CrossRef]

- Harb, A.S.M. The Role of External Audit in View of Sudden Financial Collapses on the Jordanian Commercial Banks Sector. International Journal of Financial Research 2020, 11, 218-228. [CrossRef]

- Sartawi, I.I.M.; Hindawi, R.M.; Bsoul, R. Board composition, firm characteristics, and voluntary disclosure: The case of Jordanian firms listed on the Amman stock exchange. International Business Research 2014, 7, 67. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Dave, T. A study on the impact of corporate social responsibility on financial performance of companies in India. Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation 2020, 16, 229-237. [CrossRef]

- Elfeky, M.I. The extent of voluntary disclosure and its determinants in emerging markets: Evidence from Egypt. The Journal of Finance and Data Science 2017, 3, 45-59. [CrossRef]

- Dolinšek, T.; Tominc, P.; Lutar Skerbinjek, A. The determinants of internet financial reporting in Slovenia. Online Information Review 2014, 38, 842-860. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, W.A.W.; Percy, M.; Stewart, J. Determinants of voluntary corporate governance disclosure: Evidence from Islamic banks in the Southeast Asian and the Gulf Cooperation Council regions. Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics 2015, 11, 262-279. [CrossRef]

- de La Bruslerie, H.; Gabteni, H. Voluntary disclosure of financial information by French firms: Does the introduction of IFRS matter? Advances in Accounting 2014, 30, 367-380.

- Carvalho, A.O.; Rodrigues, L.L.; Branco, M.C. Factors influencing voluntary disclosure in the annual reports of Portuguese foundations. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 2017, 28, 2278-2311. [CrossRef]

- Aljifri, K.; Alzarouni, A.; Ng, C.; Tahir, M.I. The association between firm characteristics and corporate financial disclosures: evidence from UAE companies. The International Journal of Business and Finance Research 2014, 8, 101-123.

- Malak, S.S.D.A. The voluntary disclosure of Malaysian executive directors’ remuneration under an evolving regulatory framework. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2014, 164, 535-540. [CrossRef]

- Taleb, H.; Maddocks, S.E.; Morris, R.K.; Kanekanian, A.D. Chemical characterisation and the anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic and antibacterial properties of date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Journal of ethnopharmacology 2016, 194, 457-468. [CrossRef]

- Areiqat, A.Y.; Al-Ali, A.H.; Al-Yaseen, H.M. AGRICULTURAL SOCIO-ECONOMIC WINDOW IN ONE PROJECT PALM FRONDS RECYCLING IN JORDAN. 2024.

- Alodat, A.Y.; Al Amosh, H.; Khatib, S.F.; Mansour, M. Audit committee chair effectiveness and firm performance: The mediating role of sustainability disclosure. Cogent Business & Management 2023, 10, 2181156. [CrossRef]

- Karamanou, I.; Vafeas, N. The association between corporate boards, audit committees, and management earnings forecasts: An empirical analysis. Journal of Accounting research 2005, 43, 453-486. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.; Goodwin-Stewart, J.; Kent, P. Internal governance structures and earnings management. Accounting & Finance 2005, 45, 241-267. [CrossRef]

- Mangena, M.; Chamisa, E. Corporate governance and incidences of listing suspension by the JSE Securities Exchange of South Africa: An empirical analysis. The International Journal of Accounting 2008, 43, 28-44. [CrossRef]

- Mnif Sellami, Y.; Borgi Fendri, H. The effect of audit committee characteristics on compliance with IFRS for related party disclosures: Evidence from South Africa. Managerial Auditing Journal 2017, 32, 603-626.

- Venturelli, A.; Pizzi, S.; Caputo, F.; Leopizzi, R. Integrated reporting assurance: First evidences after the transposition of Directive 95/2014/EU. RIVISTA ITALIANA DI RAGIONERIA E DI ECONOMIA AZIENDALE 2019, 91-104.

- Abdullah, K.; Ahmad, M. Compliance to Islamic marketing practices among businesses in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Marketing 2010, 1(3), 286-297. [CrossRef]

- Madi, H.K.; Ishak, Z.; Manaf, N.A.A.M.A. Audit committee characteristics and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Malaysian listed firms. Terengganu International Finance and Economics Journal (TIFEJ) 2017, 3, 14-21.

- Ashfaq, K.; Rui, Z. Revisiting the relationship between corporate governance and corporate social and environmental disclosure practices in Pakistan. Social Responsibility Journal 2019, 15, 90-119. [CrossRef]

- Madi, H.K. Do Level of Audit Committee Independence and Types of Financial Expertise Affect Corporate Voluntary Disclosure: Evidence for an Emerging Economy. European Journal of Business and Management Research 2022, 7, 14-21. [CrossRef]

- Albitar, K. Firm characteristics, governance attributes and corporate voluntary disclosure: A study of Jordanian listed companies. International Business Research 2015, 8, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Basah, M.Y.A.The impact of Shariah approved companies on the relationship between corporate governance structure and voluntary disclosure of interim financial reporting in Jordan. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences 2015, 5, 66-85. [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A.M.; Hamdan, A.M.M.; Zureigat, Q.; Dhaen, E.S.A. Does voluntary disclosures contributed to the intellectual capital efficiency? International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital 2019, 16, 145-179.

- Al-Musali, M.A.; Qeshta, M.H.; Al-Attafi, M.A.; Al-Ebel, A.M. Ownership structure and audit committee effectiveness: evidence from top GCC capitalized firms. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 2019, 12, 407-425. [CrossRef]

- Md Zaini, S.; Sharma, U.; Samkin, G.; Davey, H. Impact of ownership structure on the level of voluntary disclosure: A study of listed family-controlled companies in Malaysia. In Proceedings of Accounting Forum; pp. 1-34.

- Akhtaruddin, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Hossain, M.; Yao, L. Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure in corporate annual reports of Malaysian listed firms. Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research 2009, 7, 1-19.

- Muttakin, M.B.; Subramaniam, N. Firm ownership and board characteristics: do they matter for corporate social responsibility disclosure of Indian companies? Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 2015, 6, 138-165. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).