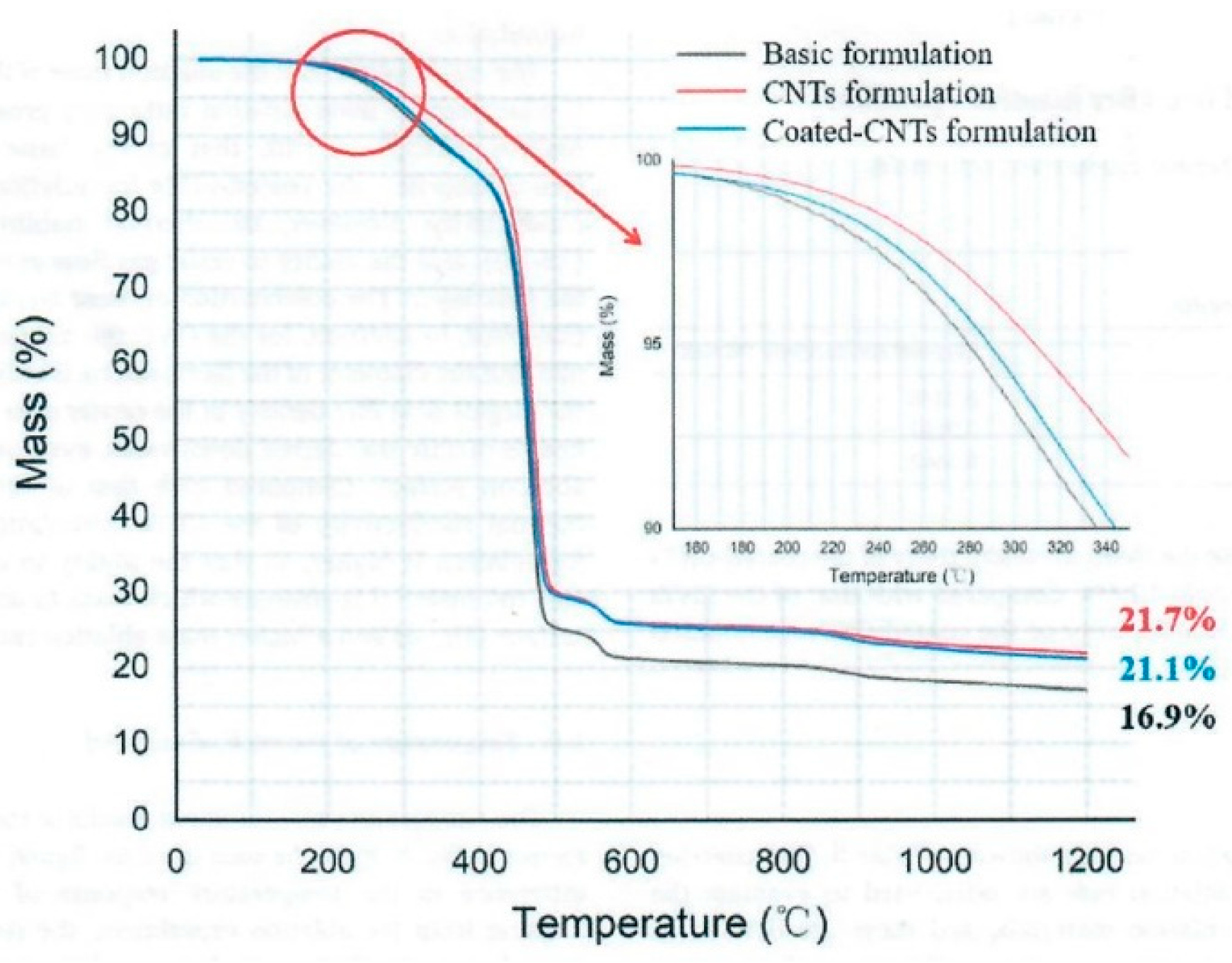

As a nanoporous material with ultralow conductivity, aerogels have attracted considerable interest in applying the technique to TPS for aerospace. Aerogels encompass a wide range of compositions such as, 1) Inorganic oxide aerogels and composites for thermal protection – SiO2, Al2O3, ZrO2, multi-oxide like Al2O3/SiO2, ZrO2·SiO2 some of which have been examined in aerospace applications. 2) Organic aerogels and composites for thermal protection – phenolic resin and polyimide. 3) Carbon aerogels and composites for thermal protection. 4) Carbide (SiC and other carbides) aerogels and composites for thermal protection. However, SiO2, silicon oxy carbide, phenolic resin and/or silica hybrids, and carbon aerogel will be discussed as aerogel components.

The NCF-PR aerogel composite possesses relatively high compressive strength (1.48 to 11.02 and 0.83 to 4.90 MPa in xy and z directions, respectively), and low thermal conductivity [0.131 to 0.230 and 0.093 to 0.180 W/(m-K) in the xy and z directions, respectively]. More importantly the NCF-PR aerogel composite exhibits good thermal insulation and ablation performance in an arc jet wind tunnel simulated environment [heat flux of 1.5 MW/m2 (115 W/cm2) for 33 s] with a low linear ablation rate (sample NCF-PR1/2 exhibited a linear ablation rate value of 0.029 mm/s and the lowest of all samples), internal temperature peaks below 90°C at 38 mm in-depth thermocouple position when the surface temperature exceeds 2,000°C. Thus, this early publication of a carbon fiber felt/phenolic resin composite aerogel suggested anticipated further publications with aerogel structural modification of the fiber reinforced composite systems with expected improved ablation performance.

The ablation performance of HARLEM was determined via arc jet testing. Cold-wall heat flux of 5.4 MW/m2 (540 W/cm2) for 30 s was used and a recession rate of 48 µm/s. was measured in-situ by photogrammetry. The authors developed a relationship that considers the effective heat of ablation (heff) as it relates to cold-wall heat flux value divided by the product of the apparent density of HARLEM (0.27 g/cc) and the surface recession rate. An effective heat of ablation value of 417 MJ/kg was determined for HARLEM. Other effective heats of ablation for a variety of carbon-phenolic ablators tested in air at plasma wind tunnel facilities are tabulated by the authors and include ASTERM with values ranging from 65.7 to 182.6 MJ/kg as well as PICA with a wide range of values from a low of 43.5 to a high of 382.7 MJ/kg. PICA surface recession rates were higher than surface recession rates for ASTERM and HARLEM despite low densities of the carbon-phenolic ablators.

4.2. Phenolic Silicon Interpenetrating Aerogels

An unusual proposed interpenetrating aerogel nanocomposite based on silicon-oxy-carbide (SiOC) and phenolic resin was reported by the Zhang group [

30]. The objective of the Jin et al. study was the improvement of the oxidation resistance of PICA like ablators due to the 3D interconnection of composite microstructure of those carbon containing materials, such as carbon fiber and phenolic resin which are susceptible to oxidation. A unique multiscale needled carbon fiber felt reinforced by silicon-oxy-carbide/phenolic interpenetrating aerogel nanocomposite was proposed as follows: the needled CF felt (NCF) was reinforced by SiOC by the sol-gel in-situ method on the felt. Phenolic aerogel was prepared and introduced into the voids of the felt-SiOC by vacuum impregnation and sol-gel phase separation induced by high temperature. The overall process is shown in

Figure 18.

The preparation of SiOC aerogels involved the addition of methyltrimethoxysilane (MTMS) to dimethyldiethoxysilane (DMDES) in ethanol with various proportions of MTMS to DMDES with distilled water and ammonia. Needled carbon fiber felt was impregnated with the SiOC aerogel solution, placed in a sealed vessel, and heated to 70°C in an oven for 14 hours for curing and crosslinking. After drying at 100°C, the SiCF felt aerogel was obtained. The SiCF felt aerogel was immersed in a PF, HMTA, and EG solution. Weight ratio of PR, HMTA, and EG was 1:0.075:5. The sealed vessel with intermittent vacuum between 0.10 and 0.01MPa was applied 3 times, by maintaining 60 minutes each time for satisfactory vacuum impregnation. Cure conditions were from 120°C to 180°C for multiple hours. The SiCF/PR wet gel was air dried for 72 hours at 25°C. The authors claim that the SiCF/PR aerogel method is a robust multistage strategy based on sol-gel and polymerization induced phase separation (PIPS) methods (

Figure 18, (a)-(c)). The attractive features of NCF as reinforcement were the low density of 0.20 g/cc, 86.7% high porosity, excellent heat resistance, and thermal insulation in the z direction due to the anisotropic structure of NCF (

Figure 18 (a)). The SiOC was prepared in-situ in the NCF via impregnation of the precursor sol, crosslinking, curing and drying (

Figure 18 (b)). The PR sol was vacuum impregnated into the prepared SiCF followed by in-situ sol-gel polymerization reaction, curing, solvent replacement and drying for the formation of the phenolic aerogel that finally resulted in the successful preparation of SiCF/PF with a multiscale structure (

Figure 18 (c)-(d)). The multiscale architecture of the SiCF/PR can be seen in

Figure 18 (f)-(h). The authors maintain the hierarchical SiOC-PR interpenetrating aerogels are uniformly inserted within the NCF and infiltrate the fiber surface due to multiple vacuum impregnation procedures and the relatively small particle size of the SiOC and PR ranging from 1µm to 70 nm.

The SiOC aerogel possesses a microscale bi-continuous framework and grape-like microstructure composed of primary silicon microspheres. The resulting aerogel network consists of micron sized silicon particles and nanoscale phenolic gel particles filling the gap and covering the surface of the NCF by vacuum infiltration. TGA char analyses of the SiCF/PR conducted at a rate of 5°C/min increased with increased amount of silane and indicated that the SiOC segment improved the thermal stability of the composites. TGA char residue (5°C/min to 1,000°C in argon) for phenolic aerogel NCF to SiOC-PR NCF interpenetrating aerogels increased from 75.96% to 80.59%, respectively. The multiscale nanocomposites exhibit excellent compression strength properties with the values approaching 5.83 and 4.57 MPa in xy and z directions, respectively while maintaining 81% of the maximum stress after 100 cycles and a low thermal conductivity of 0.068 W/(m-K). OTB ablation conditions involved a heat flux of 1.5 MW/m2 (150 W/cm2) for 300 s with the following results: the linear ablation rate dropped from 0.0282 to 0.0109 mm/s with the introduction of the SiOC aerogel leading to a remarkable 61.35% reduction whereas the mass loss rates exhibited less of a decrease of 0.0186 to 0.0157 g/s. It is apparent that the SiOC greatly enhances the oxidation ablation performance of the phenolic aerogel NCF.

The Zhang group of the Harbin Institute applied a similar multiscale nanocomposite type procedure using needled quartz fiber felt [

31] rather than needled carbon fiber felt [

30]. The SiOC aerogel was introduced into needled quartz fiber felt (QF) with a density of 0.20 g/cc and high porosity of 90.9% using similar SiOC aerogel conditions as in earlier publication [

31]. The SiOC aerogel was prepared using methyltrimethoxysilane and dimethyldiethoxysilane in ethanol followed by distilled water and ammonia. The resulting SiOC aerogel mixed solution was vacuum impregnated into the needled quartz fiber felt, transferred into a sealed container and oven heated at 70°C for 14 hours for crosslinking and curing. The SiQF aerogel was immersed into a mold containing phenolic resin composition consisting of phenolic resin (PR), hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA), and ethylene glycol (EG). The mold was sealed, cyclically vacuumed from 0.100 to 0.010 MPa and held for 30 minutes. Then the mold was heated from 120°C to 180°C for multiple hours yielding SiQF/PR aerogel with interpenetrating SiOC-phenolic aerogel nanocomposite.

The authors claim that the texture of the SiQF/PR nanocomposite is uniform and the SiOC aerogel microspheres have uniformly filled the quartz fiber felt with a typical size of 1 µm and a final density of 0.30-0.35 g/cc. Further the PR aerogel nanoparticles are uniformly distributed in the SiQF aerogel with a size of 70 nm that completely penetrate the surfaces of the fiber and the SiOC microspheres. Hence the multiscale network of the SiQF/PR nanocomposite is homogeneous from the macroscopic scale to the nanoscale. SEM results indicate that the particle size increased from 0.289 to 1.442 µm as the SiOC composition was increased. The SiQF/PR exhibited excellent mechanical properties, such as compressive strength of 4.20 and 3.34 MPa in the xy and z directions, respectively. Thermal stability of SiQF/PR via TGA (RT to 1,200°C at 5°C/min in argon and air, respectively) exhibited char residues of 82.7% in argon and 66.3% in air. Flame-retardant performance conditions using oxyacetylene flame with a heat flux of 1.8 MW/m2 (180 W/cm2) for 120 s showed a surface temperature of 1,954°C and a backside temperature of 108°C (30 mm thermocouple depth) for QF/PR (quartz felt phenolic aerogel solely) while SiQF/PR exhibited surface temperature of 1,896°C and a backside temperature of 56°C (30 mm thermocouple depth). The authors mention that the linear ablation rate reduces from 0.029 mm/s for QF/PR to 0.023 mm/s SiQF/PR under these modified OTB conditions. These ablation temperature values, and ablation rates do not compare as favorably with the recent OTB ablation data of SiCF/PR (needled carbon fiber felt with SiOC – phenolic interpenetrating aerogel nanocomposite) reported by the Zhang group earlier.

Wang and co-workers [

32,

33] treated needled quartz fiber felt (NQF) possessing a density of 0.20 g/cc with 3 kinds of ceramic particles, such as ZrB

2 (500-800 nm), SiO

2 (20-50 nm), and glass melt flux ultrasonically mixed in phenolic resin. The needle quartz fiber felt was surface impregnated with the ceramic phenolic resin mixture to a depth of 3 mm of the felt and cured at 150°C/3hr. The upper portion of the surface treated NQF was infused with phenolic resin (PR), hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA), and ethylene glycol (EG) solution and placed in a Teflon mold. The mold was sealed, cured from 100°C to 175°C for multiple hours. The gel with NQF/CR fabric was heated to 70°C for 72 hours followed by repeated washing with ethanol several hours to remove EG. It was dried at RT to a constant dry weight.

Figure 19 shows the overall process with a lower layer containing dense layer of ceramic resin and the upper layer containing phenolic aerogel.

The NQF/CR/PR composites possessed densities that ranged from 0.62 g/cc to 0.70 g/cc for densified and graded structure. The phenolic aerogel network was uniformly embedded on the surface of the upper portion of the quartz fiber felt. The composite is proposed as possessing an anisotropic structure due to the direction of the interior fibers. Most fibers are random and disorderly distributed perpendicular to the thickness direction with only a few needle-like fiber bundles being parallel to the thickness direction. The dense layer provided ablation resistance while the lightweight layer with phenolic aerogel maintained reduced weight and attractive thermal insulation for the composite. SEM images of

Figure 20 (b) to e provide microstructures of NQF, dense surface layer, internal layer, and phenolic aerogel. TGA data (TGA conditions: 25°C to 1,000°C at 5°C/min in argon) for the dense layer was 71.35% residual char while the internal lightweight layer char was 80.69%. The dual layer graded structure contained a dense layer by impregnating with ceramic particles to improve ablation resistance while the lightweight layer by impregnating the other areas of the felt with the aerogel precursor solution maintained “lightweight-ness” and thermal insulation of the composite. The tensile and bending strength for the dense layer is 39.2 MPa and 57.2 MPa; values attributable to the dense layer in the xy direction. OTB data for the dual layer system [1.5 MW/m

2 (150 W/cm

2) for 90 s] with linear and mass rates of 0.010 mm/s and 0.020 g/s, respectively at a high temperature exceeding 1,700°C. Backside temperature peaks at 52°C within 3 minutes and 127°C within 5 min when the surface temperature exceeded 1,100°C. The resulting dual layer quartz exhibited excellent thermal insulative and ablation resistant properties under OTB conditions.

Studies by Wang and co-workers [

34] considered a similar multi-layer composite construction as the previous paper whereby ablation resistant ZrB

2 and radiation resistant SiC particles are ultrasonically stirred in phenolic resin by preparing the following samples in

Table 5.

The mixed ceramic particles in phenolic resin (PR) were used to prepare a surface densified layer by surface impregnating Quartz felt (QF) possessing a density of 0.14 g/cc and needled punched in the thickness direction. ZrB

2 (0.8-1 µm) and SiC (500-800 nm) were used to impregnate the QF felt to a depth of 3 mm and curing for 4 hours at 120°C. Phenolic formulation consisting of PR to ethylene glycol (EG) was 1:5, followed by added hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA), and (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES) to impregnate the upper layered felt by the phenolic formulation. The total resin system with quartz felt was sealed in a Teflon mold, cured at 100°C to 175°C for multiple hours. The resulting composite densities varied from 0.368 to 0.400 g/cc depending on CR

x used (

Table 5). TGA data (TGA conditions: 25°C to 1,100°C under argon atmosphere but no heating rate reported). The dual layered aerogel composite QFPS with CR1 or QFPS1 exhibited a residual weight of 82.1% at 1,100°C. The tensile and bending strengths of the dual layered composites were 11.2 and 16.2 MPa, respectively with a volumetric rebound compressive strength of 0.48 MPa. The thermal conductivity of the internal lightweight layer was below 0.03W/(m-K) at 100°C. OTB testing [1.5 MW/m

2 (150 W/cm

2) for 90 s] resulted in a linear recession rate of 0.003 mm/s and a mass loss rate of 0.016 g/s. A backside temperature was below 70°C. via OTB conditions for 90 s. The values for linear recession and mass loss are much lower for the dual layer quartz felt as compared to the previous paper by the Hong group. SiC instead of SiO

2 was used in the lower layer as well as APTES silane for co-reaction with phenolic resin in forming a higher cross-linked aerogel. Both the use of SiC and silane forming a higher cross-linked aerogel contributed to the excellent OTB results.

The Harbin Institute group [

35] proposed that although the mechanical properties and ablation resistance of PICA-like materials are improved by selective ceramic additives, the radiation resistance of PICA remains to be improved. The authors developed a nano-TiO

2 coated needled carbon fiber reinforced phenolic resin (PR) aerogel composite with low density, excellent heat-insulating and infrared radiation shielding performance.

Figure 20 shows the procedure used by the authors.

The Titanium coated carbon fiber composition,

Figure 20 (b), TiCF/PR nanocomposite was prepared by a 2-step method as shown in

Figure 20 (a - c). Needled carbon fiber felt, density of 0.24 g/cc fiber with high porosity of 90.3% is the reinforcing agent. To enhance infrared radiation resistance, nano-TiO

2 was in-situ situated on the surface of carbon fibers after undergoing hydrolysis, nucleation, and calcination as shown in

Figure 20 (b). Then the PR aerogel generated from PR, hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA), ethylene glycol (EG), and γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES, KH-550) was prepared by the sol-gel method within the TiCF preform with the KH-550 strengthening the PR chemical bonding network,

Figure 20 (c). The lower portion of

Figure 20 shows the chemical structures of the main components and products in each preparation step.

Figure 20 (d) represents the carbon fiber structure.

Figure 20 (e) shows the transformation of tetrabutyltitanate (TBOT), deionized water (DI) and ethanol in solution to coat the CF. The TiCF preform was calcinated at 500°C for 2 hr, washed with DI, and heated at 120°C to a constant weight.

Figure 20 (f) shows the formation of the phenolic aerogel. The macro/micro morphologies that correspond to the different preparation stages are illustrated in

Figure 20 (g - j). Nano-TiO

2 adhered well to CF,

Figure 20 (g). The small TiO

2 nanoparticles (~32 nm) uniformly covered the CF surface and formed a ceramic coating after being sintered as shown in

Figure 20 (h) and the inset. The PR aerogel covered the TiCF and filled the bulk of the felt as a porous matrix

Figure 20 (i). Macro photograph of TiCF/PR is shown in

Figure 20 (j).

The microscopic morphology of TiCF/PR and TiCF shown in

Figure 21 (a) and (b) exhibits the TiO

2 coating completely enclosing the CF surface along with PR aerogel nanoparticles in (a) while (b) distinguishes solely the TiO

2 coating on CF for TiCF composition. The nano- TiO

2 is formed by a compact accumulation of nanoparticles in the size of 35 nm (

Figure 21 (c), during hydrolysis of and sintering of TBOT.

Figure 21 (d) illustrates the molar ratios of C, O, and Ti as 80%, 14%, and 3%, respectively via inset of EDS and the good interfacial contact between the nano-TiO

2 coating and the phenolic aerogel. It shows the phenolic aerogel grew directly on the coating surface and filled the coating fissures. Further the PR aerogel consisted of nanoparticle aggregates and many tiny pores due to vacuum immersion and solvation/thermal methods. SEM images shown in

Figure 21 (e) and (f) indicate pore size of 20 nm-1 µm. the CF, TiO

2 coating, and porous PR aerogel synergistically constructed the ternary TiCF/PR IR radiation –resistant composite.

The resulting aerogel possessed a low density of 0.30-0.32 g/cc, low thermal conductivity of 0.034 and 0.312 W/(m-K) in the z and xy direction and excellent thermal stability with 13.9% residual weight at 1,300°C in air. As expected, the TiCF/PR composite exhibited excellent antioxidant ablation and IR radiation shielding performance in a high temperature heated environment. OTB at 1.5 MW/m2 (150 W/cm2) for 150 s, resulted in linear ablation rate was 26.2 µm/s and the mass loss rate was 8.4 mg/s with the backside temperature of 179.1°C. The novel TiCF/PR aerogel composite with low density and excellent heat insulation met the objective of providing IR radiation resistance for Thermal Protective material.

To further improve TiO

2 coated needled carbon fiber felt (density of 0.20 g/cc and 85% porosity), Wang and co-workers [

34] (Wang et al., 2023) used a co-gelation method by combining tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) and tetrabutyl titanate (TBOT) raw materials to prepare TiO

2-SiO

2 composite aerogels through co-gelation. The authors consider the co-gelation method the most promising way to strengthen the cross-linked structure and achieve microstructural modulation, overcoming the defect of weak chemical bonding of TiO

2. The TiO

2-SiO

2 provides a low thermal conductivity of 0.024 W/m-K for acceptable thermal insulation performance. The insertion of Si-O bonds (bond energy of 452 kJ/mol) in the coupling network improved the mechanical strength of the material. The co-gel method allowed the homogeneous introduction of TiO

2, and its synergistic cross-linking strategy enabled the adoption of other stronger covalent bonds in the Ti – O framework to improve the structural strength and heat resistance of the matrix. As shown in

Figure 22 (a) – (b) the fabrication of TiO

2-SiO

2 was supported by the co-gel methodology (d). Combining TEOS, TBOT and Methyltrimethoxysilane (MTMS) in aqueous ethanol with a small amount of acetic acid was carried out. Acetic acid slows down individual gelation reactions and allows the desired slow mixing and co-gelation. The resulting solution is placed in a PTFE coated vessel. The needled CF felt was inserted into the vessel and impregnated under a vacuum of 0.1 MPa for 30 minutes followed by heating from 80°C to 120°C for multiple hours. After curing, the sample was dried at 80°C, calcined in a muffle furnace at 400°C for 2 hours at a heating rate of 2°C/min.

The resulting C

f/TS was identified as C-

x-t with its microscopic structure displayed in

Figure 22 (g) where

x denotes the molar ratio of the TEOS component (0.25);

t denotes the heat treatment (calcination) temperature (400°C). The TiO

2-SiO

2 aerogel was identified as TS-

x-t or TiO

2-SiO

2 -0.25-400. Next, the phenolic resin composition [phenolic resin (PR), hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA), and ethylene glycol (EG)] is introduced into the PTFE lined vessel containing needled carbon felt with TiO

2-SiO

2 (C

f/TS), vacuum impregnated for 30 min, sealed, and cured from 120°C to 180°C for multiple hours. Removal of EG and drying at 80°C is shown in

Figure 22 (c) and (e). The final needled carbon felt with TiO

2-SiO

2 impregnated with phenolic aerogel (C

f/TS-PR) was named CP-

x-t, Figure 22 (f), and the microstructure of the synthesized C

f/TS-PR composite is shown as

Figure 22 (h).

Microscopic morphology of different calcination temperatures indicated that to fully utilize the antioxidant and radiation resistance of TiO2-SiO2 coating, a temperature of 400°C is adequate for a suitable thickness and defect free coating. Characterization of the Cf/TS-PR composites begin with the structure of the TiO2-SiO2 coating surrounding the CF structure. It remains intact while the nanoscale PR aerogel filled in the voids of the fiber skeleton and encapsulated the TiO2-SiO2 coating surface as well as most crack defects facilitated by vacuum-assisted process. FTIR showed characteristic peaks for Ti-O and Ti – O – Si bonds indicating the incorporation of TEOS to introduce the Si –O – Si bonds to the original TiO2 structure. It indicates that the TiO2-SiO2 coating with Ti –O bonds as the main network with Si – O bonds as the minor component was successfully accomplished through the sol-gel method.

Furthermore, the Cf/TS-PR exhibited a similar pattern compared to PR indicating that the PR aerogel inside the Cf/TS maintained its original chemical structure. The Cf/TS-PR composites exhibited desirable mechanical properties, a low thermal conductivity of 0.0756 W/(m-K), remarkable thermal stability and outstanding ablation resistance. Linear ablation rates are as low as 0.004 and 0.003 mm/s at 1.0 (100 W/cm2) and 1.5 MW/m2 (150 W/cm2) for 240 s, respectively. Mass loss rates are similarly low as 0.006 and 0.009 g/s for 1.0 (100 W/cm2) and 1.5 MW/m2 (150 W/cm2) for 240 s, respectively. A low backside temperature of 108°C at 120 s for heat flux of 1.5 MW/m2 (150 W/cm2) was observed when the surface temperature was 1,400°C. These outstanding ablation resistance properties of the generic Cf/TS-PR are identified with CP-0.25-400 composite with ratio of CF felt with 0.25 molar ratio of TEOS and 400°C, temperature of calcination with 20 parts of PR in the CP-0.25-400 composite. This Ti-Si binary modified carbon felt/phenolic aerogel composition exhibited the best ablation resistance to date as compared to several lightweight ablative materials reported previously by several global investigators.

4.3. Phenolic Aerogel without Reinforcement

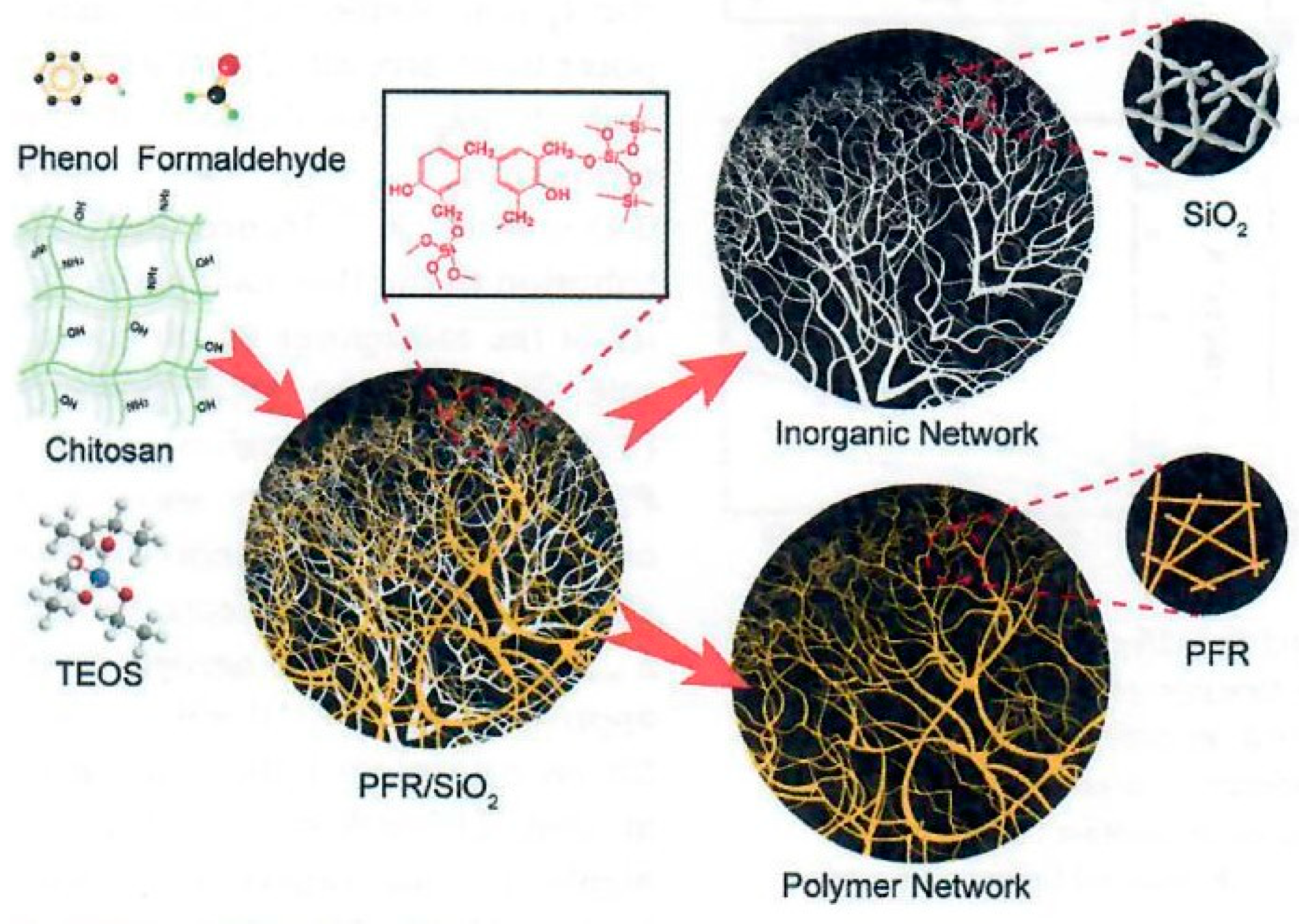

Xiong and Zhang with their co-workers [

36,

37] decided to strengthen the Benzoxazine (Bz) precursor aerogel by the addition of inorganic nanoparticles, such as SiO

2 to Bz aerogel to improve thermal stability, mechanical properties, and ablation resistance. Two types of Polybenzoxazine (PBz) aerogels containing nano-silica were prepared by different routes. One method involved the use of tetraortho silicate (TEOS) into the PBz solution as a silica source, hydrolyze, and copolymerize to form polybenzoxazine/silica aerogels (PSAs) after an ambient drying process. The other is to add chitosan chains to the PBz/silica system and copolymerize to form polybenzoxazine/silica/chitosan aerogels (PSCAs). The two aerogels exhibited a 3D nanoporous network structure, light weight, self-extinguishing properties, thermal stability, and excellent mechanical strength. The PSAs possess better thermal stability and mechanical strength, but poor thermal insulation compared with PSCAs. The PSAs and PSCAs were prepared by the introduction of silica organic phases using different chemical routes by the sol-gel method and ambient pressure drying process.

Bz was dissolved in DMF, deacetylated chitosan in ethanol/water with 2% acetic acid (only for PCSAs) was added followed by TEOS. Subsequently the composition was mixed, transferred to a sealed vessel, and heated to 60°C. Once the gel formed, solvent exchange with ethanol (8 times) for DMF removal, dried to obtain PSAs and PSCAs aerogels. The density of PSAs was 0.40 g/cc while PSCAs were lower in density or 0.26 g/cc. The pore size distribution of the 2 samples is mainly in the nanoscale range of 5-35 nm. Thermal conductivity of PSAs and PCSAs are 0.064 and 0.037 W/(m-K), respectively at RT. Compressive strength or the PSAs is reported to be 3.62 – 7.74 MPa depending on % strain. PCSAs compressive strength is much lower. No OTB data was reported for the PBz/Silica hybrid aerogels other than self-extinguishing fire resistance performance. The PBz/Silica hybrid aerogels with CF or Quartz felt reinforcement are suggested as the next steps in determining whether PBz/Silica hybrid aerogel has merit in TPS area.

An improved process for phenolic aerogel preparation using combined interfacial polymerization and sol-gel conditions was reported by Wu and co-workers [

38]. These studies are conducted without any reinforcing fiber or felt material. The resulting aerogels known as “Phenolic resin aerogel water-assisted method” (PRAW) exhibited porous structural features with a mesoporous diameter of 80 nm attributable to the stacking of the thick-connected nanoparticles. The authors claim that the overall process is facile, environmentally friendly, moderate in cost, and involves a relatively short cycle resulting in PRAWs with superior mechanical performance with compressive strength of 18.33 MPa at 50% strain and attributable to the thick-connected nanoparticles construction of the PRAWs. The authors implied that previous phenolic aerogels were relatively thin in cellular structure and moderately fragile resulting in aerogel fracture and ultimately disintegrate into powder. The overall method is shown in

Figure 23.

The nanostructured composite occurs through water assisted sol-gel polymerization for the PRAWs with superior mechanical properties and excellent thermal insulation. The PRAWs were prepared through a phase-interface reaction like interfacial polymerization with the reaction scheme shown in

Figure 23. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), deionized water (DIW) followed by γ-(2,3-epoxypropoxy) propyltrimethoxysilane (KH-560) mixed in a reactor followed by added phenolic resin (PR). The resulting mixture was transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated from 80°C to 180°C for multiple hours. The final PRAW was washed with DIW, heated at 50°C/5hr to remove SDS. Finally, PRAW was obtained after drying at 110°C for 12hrs. Different PRAWs are obtained depending on the amount of KH-560 added. The lower portion of

Figure 23 suggests the mechanism of preparing phenolic aerogel via phase separation polymerization involving the co-reaction of phenolic resin with KH-560 and the resulting proposed structure of the PR-epoxy network.

The authors state that curing with the epoxy KH-560 endows PR with a high crosslinking density and high molecular weight resulting in the high strength of the PRAWs. SEM of the PRAWs reveals a porous framework consisting of spherical particles with diameter of 80 nm forming a continuous structure of both micropores and mesopores or a “bead string” structure. Phenolic particles are homogeneous with an average size of 90 nm. Mechanical properties of the PRAWs displayed maximum compressive strength varying from 2.4 MPa to 18.3MPa, when compressed to disintegration. The corresponding compressive modulus is from 23.1 MPa to 78.2 MPa for the PRAWs. According to the authors none of the samples exhibits brittle failure due to the deformation space inside the nanopore structure of the material. Compared with “thin-connected” traditional phenolic aerogels, the “thick-connected” phenolic aerogel PRAWs can reduce stress concentration during compression. Benchmarking the performance by considering specific compressive modulus versus specific compressive strength of the “thick-connected” of the PRAWs versus other “thin-connected” phenolic aerogels reported in the literature, PRAWs exceeded all other phenolic aerogels in performance.

The authors viewed the preparation of normal organic aerogels linked necks occurs during the condensation of polymer particles during slow gelation and increase to a specific size through the dissolution and re-precipitation of polymer agglomerates during aging. In the current work [

38], the slow polymerization of PR with KH-560 in deionized water facilitated the formation of large polymer clusters and compacted particle connections to further increase the strength of the internal skeleton structure. Thus, the resulting material, PRAW, was endowed with outstanding mechanical properties, especially PRAW with intermediate amount of KH-560 that can be compressed by 50% without catastrophic collapse due to the favored deformation space provided in this material. Remarkably PRAW can be dried in ambient pressure due to a combined strong nanostructure configuration and the presence of macro-pores which effectively resist capillary forces during ambient pressure drying.

The thermal stability of the PRAWs was studied by TGA and a carbon residue of greater than 55% is observed for the PRAWs and consistent with phenolic thermal performance for TPS. Thermal conductivity of the PRAWs varied from 0.0617 to 0.0718 W/(m-K) with PRAW (intermediate amount of KH-560) exhibiting the lowest value of 0.0617 W/(m-K). These low thermal conductivity values are attributable to the inherent porous structures and low densities of the aerogels. The superior insulation properties are based on a balance between solid-phase heat transfer through the framework and gas-phase heat transfer through the porous structure. Without reinforcing fiber or felt, no OTB ablation data is reported except PRAW exhibited excellent dynamic thermal insulation performance for a thickness of 20 mm, as well as high temperature resistance (1,200°C) with a final backside temperature of 57.7°C after 5 minutes. It will be interesting to determine whether these attractive ablation characteristics carry over when the same chemical transformation occurs when a carbon fiber felt reinforcing component is used.