1. Introduction

In recent years, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic led numerous countries to close their borders and implement social distancing measures. This resulted in significant changes in people’s lifestyles and had substantial social and economic repercussions worldwide. In the sports industry, the United Kingdom government temporarily suspended outdoor sporting events, and the Premier League had to resume its matches without spectators in the stadium [

1]. Additionally, several local governments in the United States recommended not holding professional sporting events, resulting in the suspension or delay of ongoing seasons in the NHL, NBA, MLB, and MLS [

2].

This adversity extended beyond local sporting events and affected mega sporting events, as exemplified by the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic Games (Beijing 2022). The Beijing 2022 organising committee decided not to sell tickets to spectators from outside mainland China, aligning with China’s zero COVID-19 policies [

3], and an integrated cluster system was introduced to ensure the separation of Beijing 2022 participants from local residents [

4]. To some extent, the goals of these preventive measures were achieved. However, because of the strict protocols enforced during the Games, no one from outside the closed loop could enter and no one from inside could exit, meaning that there were no interactions between the participants and the local community [

5]. By relying primarily on media coverage, Beijing 2022 encountered physical limitations in its endeavours to promote tourism, culture, and Olympic values to the world, contrary to initial expectations.

The international exposure, spread of culture, and promotion of peaceful values in sports make the Olympics a valuable instrument for nations to leverage soft power in pursuit of both national and international objectives while enhancing their global image [

6]. Mega sporting events have served as significant catalysts for transformation at the local, regional, and national levels [

7,

8]. In particular, mega sporting events play a pivotal role in enabling host cities to stimulate urban regeneration and improvement [

9,

10,

11]. However, as Anholt [

12] noted, building a destination image requires more than just hosting sporting events; policies, products, people, culture, tourism, and businesses must collaborate to enhance the city’s reputation.

A destination image is defined as the aggregate of a person’s cognitive beliefs, ideas, and impressions related to a specific destination [

13]. As the formation of a city image is the result of a bilateral process involving both the observer and the environment [

14], public images are collective mental representations shared by many local residents. Thus, city image plays a crucial role in city brand development and requires consideration from the perspectives of two groups: tourists and residents [

15].

Some scholars suggest that city image is an interactive system of thoughts, opinions, and intentions concerning a city [

16]. Garnering resident support is crucial for the development, planning, successful operation, and sustainability of cities. Additionally, examining the residents’ loyalty and satisfaction with the city helps to ensure that hosting a mega sporting event does not cause a decline in residents’ quality of life, which could erode their support of the event.

In the context of the sports industry, studies have considered city image, satisfaction, and loyalty as key indicators when investigating the causality and impacts of the values of sporting events [

17,

18,

19]. Consistent findings indicate that hosting sporting events creates a positive impact on these indicators by endorsing city policies [

20], fostering sustainable development [

21], and encouraging voluntary citizen participation [

22].

Ensuring city satisfaction and loyalty are essential intangible values that contribute to supporting city policies, stimulating cooperative intentions and voluntary engagement, and improving the quality of life. Furthermore, the perceived psychological benefits experienced by residents represent an intangible outcome of sporting events and can enhance city satisfaction with the quality of life [

23]. However, despite progress in clarifying the role of these variables in consumer behaviour, further validation is required, particularly when accounting for exceptional circumstances.

As mega sporting events are exposed to various internal and external risks, including terrorism (e.g., during the 1972 and 1996 Olympics) and financial crises (e.g., during the 1976 and 2004 Olympics), significant interdisciplinary research has been conducted on security [

24,

25,

26] and economic crises [

27,

28,

29]. Meanwhile, even though mega sporting events have recently been threatened by infectious disease outbreaks, such as the Zika virus at the 2016 Olympics and the MERS virus at the 2015 Summer Universiade, the threats posed to mega sporting events by epidemics have received less attention, and there is limited research on the impact of epidemics on hosting mega sporting events.

As a completely different type of risk, COVID-19 has emerged as a potential watershed moment due to its unprecedented global spread and the stringent containment measures implemented worldwide [

30,

31]. This makes it imperative to conduct further research on the effects of hosting mega sporting events when tourist participation is limited. Therefore, this study examines the effects of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic Games on the perceived benefits, including those related to the economy, sociocultural aspects, environment, and tourism in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study investigated the correlation between perceived benefits and city assessment factors, such as city image, satisfaction, and loyalty, from the perspective of local residents, who can be regarded as the primary beneficiaries or key stakeholders of mega sporting events. Considering the elevated potential for future pandemics, this study provides substantial value for mitigating the risks associated with hosting mega sporting events that necessitate significant financial investment in the event of an infectious disease threat.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Social Exchange and Expectancy-Value Theories

Research examining the behaviour of residents in the context of tourism development and events primarily draws upon the principles of Social Exchange Theory (SET) (e.g., [

32,

33,

34,

35]). SET has proven effective in explaining resident support as it can accommodate different perspectives influenced by experiential and psychological consequences [

36]. The primary components of the social exchange process are economic, environmental, and sociocultural benefits [

37].

Such reciprocity varies as a function of social exchange, including instrumental and emotional support, which is influenced by an individual’s role relations and the content of their exchanges [

38]. SET can explain how residents perceive the economic, environmental, and sociocultural impacts of tourism development and other related initiatives pursued by local authorities. According to SET, individuals are likely to engage in an exchange when they anticipate gaining advantages without incurring unacceptable expenses [

39].

The concept of SET can be understood within the context of process theories of motivation, which delve into how different factors affect motivation and behaviour. Expectancy-value theory is one of the most widely employed in this area [

40]. This theory states that motivation relies on three aspects: an individual’s belief in the feasibility of a particular expectation, appeal of the outcome, and anticipation of achieving the outcome [

41].

Modern expectancy-value theories [

42,

43] are based on Atkinson [

44], which pertains achievement performance, persistence, and choices to individuals’ beliefs about expectancy and task value. Atkinson proposed that achievement behaviours are shaped by achievement motives, expectations of success, and the attractiveness of the incentives. He defined incentive value as the measure of how attractive it is to succeed in a particular achievement task and pointed out that this incentive value decreases as the likelihood of success diminishes.

In this study, the object is ‘perceived benefits arising from hosting Beijing 2022’, and the resulting outcome is city brand values. Several studies have successfully applied the expectancy-value model in tourism and sport research (e.g., [

41,

45]). The theoretical framework for this study was formulated based on the literature review, as illustrated below.

2.2. Perceived Benefits of Mega-Events on Host City Image

Studies show that hosting mega sporting events can yield both economic benefits and positive impacts by enhancing the city’s brand image, increasing international status, and generating significant ripple effects for the host nation or city [

46,

47]. Horne and Manzenreiter [

48] argued that mega sporting events can lead to substantial spillover effects. Specifically, with respect to Beijing 2022, there was a critical need to raise awareness of the winter sports industry in China, elevate the country’s brand value, and enhance its political and social image to garner greater favourability.

Furthermore, mega sporting events can have a more profound impact on regional development and city image enhancement than domestic events, serving as symbolic landmarks for the host country or region [

49]. Such events can serve as potent tools for regional development policies, acting as a form of place marketing that enhances the city’s image while also stimulating tourism and investments in public services, accommodations, and infrastructure [

50].

Thomson et al. [

51] suggested that hosting mega sporting events can result in both tangible and intangible benefits, including regional economic effects, improved quality of life, heightened recognition for the host city, and the development of local infrastructure. Yang et al. [

52] discovered that local residents believe that major events improve the city’s image, infrastructure, tourism, job opportunities, and cultural interactions. In another study, Liang et al. [

53] found that social, economic, and environmental benefits significantly influenced sustainable urban development.

Despite these positive effects, conflicts may arise when the destination image perceived by residents differs from that observed by external stakeholders, potentially leading to internal discord. Discrepancies between the externally projected image and the reality experienced by residents, or an overly standardised image, can lead to dissatisfaction among residents, reducing their willingness to support tourism promotion and hindering destination development [

54]. Therefore, aligning residents’ perceived benefits with external perspectives and government investments is crucial for establishing a positive city image.

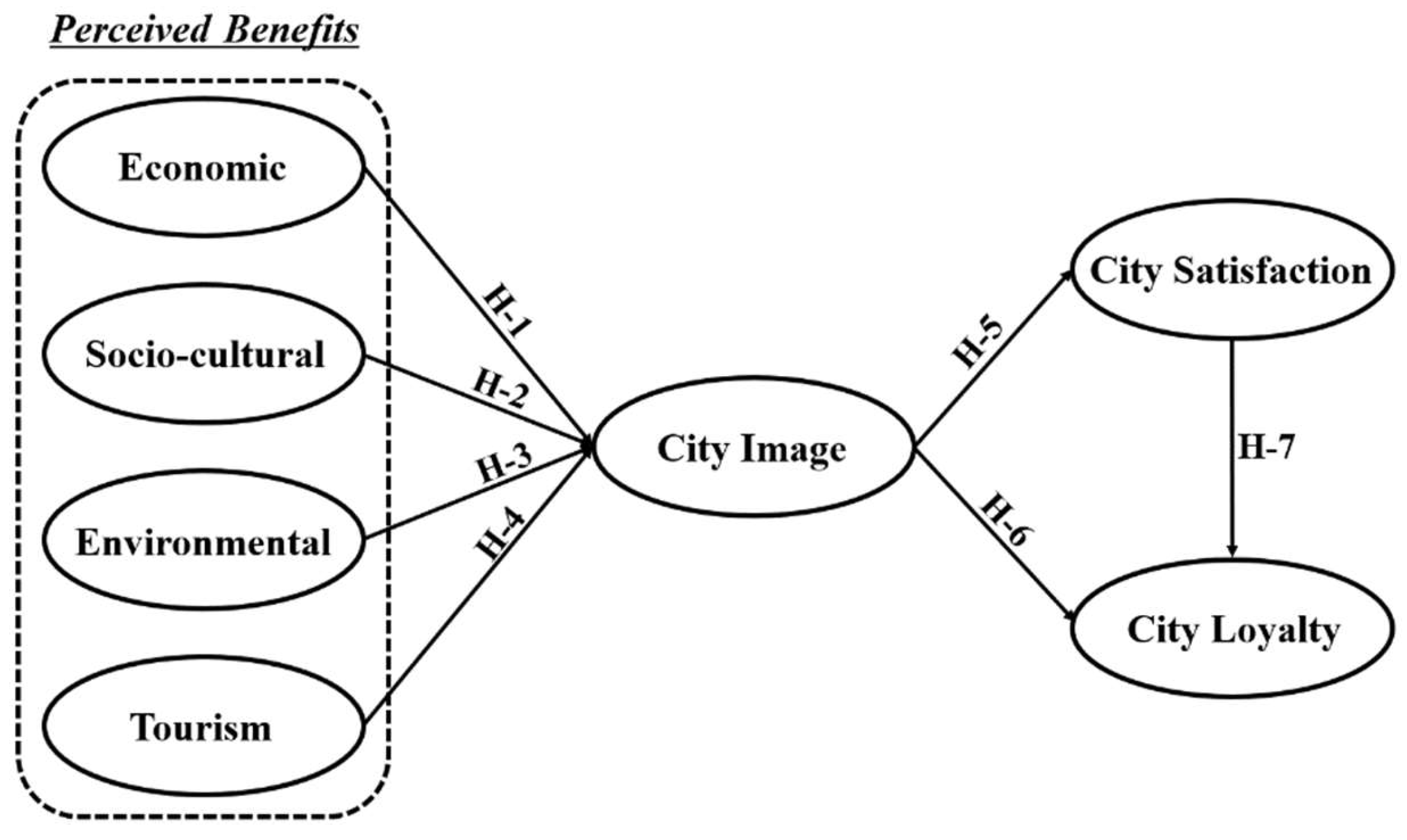

Based on empirical evidence from the literature, the proposed hypotheses focus on the correlation between perceived benefits (economic, sociocultural, environmental, and tourism impacts) and destination image. These hypotheses aim to shed light on the complex interplay between the various factors shaping city image and the outcomes of hosting mega sporting events.

H1.

Perceived economic benefits positively affect city image.

H2.

Perceived sociocultural benefits positively affect city image.

H3.

Perceived environmental benefits positively affect city image.

H4.

Perceived tourism benefits positively affect city image.

2.3. Relationship between City Image, Satisfaction, and Loyalty

Studies have explored the relationship between city image and loyalty from various perspectives and at various scopes. Lindblom et al. [

55] suggested that city image established through regional festivals can influence loyalty. Other researchers have highlighted significant connections between different variables, such as the link between tourism destination image and loyalty [

56,

57], brand image and loyalty [

58], place marketing and customer satisfaction [

59], and national image and loyalty [

60].

Lobo et al. [

22], as well as other studies, have found a strong correlation between the overall city image and loyalty towards the city as a tourism destination. Lobo et al. [

22] found that a positive city image was correlated with a higher likelihood of recommending the city in promotional efforts, leading to increased satisfaction and loyalty.

The primary objective of city marketing is to enhance both the city image and satisfaction levels. City marketing aims to boost city image and satisfaction to ultimately increase city loyalty. To achieve this, city development policies should focus on dispelling negative or ambiguous perceptions among residents, investors, and visitors, while fostering high levels of satisfaction and pride. Based on this theoretical background, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5.

City image positively affects city satisfaction.

H6. City image positively affects city loyalty.

2.4. Relationship between City Satisfaction and Loyalty

Duan and Wu [

61] found that the selection of sports events influences the local brand image and the intention to revisit, while Oshimi and Harada [

62] found that creating shared value in urban sports events positively affects the local image and loyalty of residents. Aleshinloye et al. [

63] discovered that loyalty affects intimacy, attachment to a region, and dependence. Furthermore, residents’ attitudes towards tourism policies are more positive when they have a high level of attachment to their community [

64]. Research has shown that city satisfaction as perceived by citizens directly affects city loyalty [

65].

In the tourism industry, brand satisfaction has been linked to brand loyalty and image [

66]. Ritchie et al. [

67] argued that international sports events contribute to city awareness and image, which are antecedents of city loyalty. Consumer behaviour research has consistently shown that satisfaction is a crucial factor in brand loyalty [

68]. Therefore, this study aims to analyse the relationship between city satisfaction and loyalty as perceived by residents. Based on this theoretical background, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H7.

City satisfaction positively affects city loyalty.

Figure 1.

Proposed model for the study.

Figure 1.

Proposed model for the study.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Procedure

The study data were collected from local residents in Beijing and Zhangjiakou, the venues for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics. After an extensive literature review of the measurement items, the questionnaire was comprehensively reviewed by three professors in sports management, and further refinements were made based on their feedback. A pilot survey was conducted to develop an appropriate research instrument. Pilot data (n=52) were collected from Beijing residents who experienced the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic Games. The residents were selected based on specific criteria, including their duration (more than 10 years) of residence in Beijing and their direct involvement in or impact by the event. The questionnaires demonstrated a high level of internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.870, indicating a high degree of confidence [

69].

For data collection, the convenience sampling method, a non-probability sampling method, and a self-administered questionnaire were used. The survey was carried out from 27th February to 19th March 2022, immediately after the end of the Games. An online survey company (

www.sojump.com) was used to conduct the online research; respondents were asked to answer the questionnaire after confirming their place of residence. They were informed that their participation was entirely voluntary and assured of the privacy and confidentiality of the information they provided.

Table 1.

Demographics characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographics characteristics.

| Variables |

N |

(%) |

| Sex |

Male |

475 |

54.7 |

| Female |

393 |

45.3 |

| Age group(years old) |

20–29 |

270 |

31.1 |

| 30–39 |

293 |

33.8 |

| 40–49 |

198 |

22.8 |

| 50 or above |

107 |

12.3 |

| Place of residence |

Beijing |

467 |

53.8 |

| Zhangjiakou |

401 |

46.2 |

| Education |

Middle school |

27 |

3.1 |

| High school |

366 |

42.2 |

| College or university |

458 |

52.8 |

| Graduate school |

17 |

1.9 |

| Occupation |

Student |

207 |

23.8 |

| Public servant |

89 |

10.3 |

| Private company employee |

228 |

26.3 |

| Self-employed |

173 |

19.9 |

| Professional |

72 |

8.3 |

| Labour worker |

99 |

11.4 |

| Total |

868 |

100.0 |

For the final analysis, 868 samples were recruited and 41 incomplete responses were excluded from data analysis. Male participants accounted for 54.7% (n=475) of the sample, with 467 respondents from Beijing and 401 from Zhangjiakou. Two-thirds of the sample (31.1%) were in the age group of 20–29; another 33.8%, 22.8%, and 12.3% were in the age groups of 30–39, 40–49, and 50 or above, respectively. Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to determine whether the underlying structure could form a reliable measurement model for the construct, with adjustments and modifications when necessary. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was employed to examine the relationships between perceived benefits, city image, city satisfaction, and city loyalty. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0 and AMOS 29.0.

3.2. Instruments

The instrument comprised four main variables: perceived benefits, city image, city satisfaction, and city loyalty, along with demographic characteristics. All measures in this study were taken from previous literature and measured using a 5-point Likert scale (5=strongly agree; 1=strongly disagree), allowing respondents to express the extent to which they perceived the impact as either positive or negative [

70,

71]. Regarding the items measuring perceived benefits on economic, sociocultural, environmental, and tourism effects, 16 items were adapted from Chang et al. [

72], Duan et al. [

73], and Prayag et al. [

39]. City image was evaluated using four items derived from Artuğer et al. [

74], while four items each related to city satisfaction and loyalty were adapted from Artuğer et al. [

74] and Song et al. [

57].

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Test

Following the two-step approach proposed by Anderson and Gerbing [

75], a CFA was conducted to evaluate the measurement quality of each construct. Cronbach’s alpha and construct reliability (C.R.) values were used to assess internal consistency [

76]. As shown in

Table 2, the Cronbach’s alpha scores (between .868 and .980) and C.R. (between 0.950 and 0.980) for all constructs exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.70, as recommended by Nunnally [

77], indicating that the latent variables demonstrated adequate internal consistency. Standardised factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) were used to assess convergent validity. All standardised factor loadings (between .883 and .971) were above 0.5 [

78], and all AVE values (between .826 and .924) exceeded the threshold of 0.5 [

79].

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor loading results.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor loading results.

| Factor (scale sources): Items |

Standardised

coefficient |

Unstandardised

coefficient |

t |

C.R. |

AVE |

Cronbach’s α |

| Economic |

Regional economy promotion |

.889 |

1.000 |

- |

.950 |

.826 |

.949 |

| Income increase and improvement |

.919 |

1.180 |

42.524***

|

| Employment expansion |

.923 |

1.105 |

42.959***

|

| Local public finances’ expansion |

.905 |

1.090 |

40.991***

|

Socio

cultural |

Social and cultural development |

.931 |

1.000 |

- |

.962 |

.863 |

.961 |

| Cultural standards’ enhancement |

.937 |

1.002 |

53.364***

|

| Leisure activities’ increase |

.926 |

1.055 |

51.061***

|

| Public order improvement |

.922 |

1.045 |

50.345***

|

| Environmental |

Traffic system improvement |

.937 |

1.000 |

- |

.964 |

.869 |

.963 |

| Road infrastructure enhancement |

.954 |

.992 |

58.695***

|

| Living environment enhancement |

.895 |

1.000 |

46.424***

|

| City landscape (aesthetics) enhancement |

.942 |

.992 |

55.725***

|

| Tourism |

Tourism industry development |

.966 |

1.000 |

- |

.980 |

.924 |

.980 |

| Tourism resources development |

.962 |

1.009 |

74.428***

|

| Tourism revenue increase |

.971 |

1.018 |

79.341***

|

| Tourism image enhancement |

.946 |

.970 |

66.919***

|

City

Image |

The city I live in has a wide range of local amenities available. |

.935 |

1.000 |

- |

.964 |

.870 |

.964 |

| The city I live in provides convenient transportation options. |

.936 |

.997 |

53.873***

|

| The city I live in is attractive. |

.930 |

.966 |

52.513***

|

| The city I live in has beautiful natural scenery |

.931 |

1.008 |

52.694***

|

| City satisfaction |

I am proud of the city I live in. |

.927 |

1.000 |

- |

.971 |

.894 |

.868 |

| I am satisfied with the city I live in. |

.957 |

1.041 |

57.256***

|

| I am happy to live in my city. |

.946 |

1.101 |

54.493***

|

| I enjoy living in my city. |

.951 |

1.084 |

55.629***

|

City

Loyalty |

I would recommend my city to others |

.963 |

1.000 |

- |

.962 |

.865 |

.961 |

| I will share the positive aspects of my city with others. |

.954 |

.976 |

67.187***

|

| Even if I were to leave, I would consider returning to live in this city in the future. |

.917 |

1.019 |

55.416***

|

| This city is the most suitable city for work purposes. |

.883 |

1.051 |

48.013***

|

The structural model was examined through CFA with a validation sample (n=868) using maximum likelihood estimation. This analysis aimed to detect causal relationships between the constructs. The criteria for goodness-of-fit in the CFA were set as follows: RMSEA ≤ 0.08, NFI, TLI, and CFI ≥ 0.90, in accordance with Browne and Cudeck [

80]. The measurement model indicated an acceptable model fit, with χ

2=2015.713 (df=329, p=.000), RMR=.012, RMSEA=0.077, NFI=.951, TLI=.952, CFI=.958, which indicates that all figures met the criteria for goodness-of-fit.

4.2. Correlation Analysis

A correlation analysis was conducted to confirm the correlation between the factors. The analysis revealed significant correlations between each factor at the p<.001 level. All correlation coefficients remained below 0.91, ensuring discriminant validity among the factors, and the standard value for multicollinearity was below 0.80 [

81], indicating no issues between them. Research has suggested that discriminant validity is achieved when the AVE value exceeds the squared value of the correlation coefficient. In this study, we compared the largest squared correlation coefficient value with the smallest AVE value presented in

Table 3 and found that the highest correlation coefficient value was .905 (=.819), while the smallest AVE value was .826. This confirms that discriminability among the factors was effectively established [

79].

4.3. Hypothesis Tests

To test these hypotheses, SEM was conducted using AMOS 29.0. The measurement model (see

Table 4) showed that χ

2=2105.867 (df=337, p<.001), RMR=.018, RMSEA=.078, NFI=.948, TLI=.951, and CFI=.956. According to the path coefficients, economic (=.119

***, p<.001), environmental (=.164

***, p<.001), and tourism (=.374

***, p<.001) benefits had positive effects on city image, supporting Hypotheses 1, 3, and 4, respectively. Meanwhile, as shown in

Table 5, city image positively affected both city satisfaction (=.899

***, p<.001) and loyalty (=.375

**, p<.001), indicating that higher satisfaction with hosting a mega-event led to more favourable attitudes towards the city. Thus, Hypotheses 5 and 6 were supported. City satisfaction (=.551

***, p<.001) also positively affected city loyalty; therefore, Hypothesis 6 was supported. In contrast to the theoretical expectations, the perceived sociocultural benefits (=.173, p=.012) of city image were found to be statistically non-significant. As a result, Hypothesis 2 was not supported, as it failed to demonstrate a significant influence.

4.4. Mediation Effects

This study examines the mediating effect of city satisfaction on city image and loyalty. Given the complexity of testing the mediation effects in models, the impact of mediators is typically assessed through a systematic step-by-step process [

82]. Following the approach outlined by Alwin and Hauser [

83], which involves examining how the independent variable influences the dependent variable through a mediating variable,

Table 6 presents the analysis results.

The findings showed that both the standardised path coefficient and the path coefficient decreased in the overall analysis results compared to the individual path analysis results. Importantly, all paths demonstrated statistically significant results, indicating suitable conditions for mediating effects. Furthermore, the standardised indirect effect analysis revealed that city satisfaction (indirect effect=.585, p<.01) exhibited a statistically significant mediating effect on the relationship between city image and loyalty. These findings suggest that city satisfaction plays a crucial role in mediating the relationship between city image and loyalty, highlighting its importance in shaping perceptions and fostering residents’ loyalty towards the city.

5. Discussion

This study analysed the relationship between the perceived benefits of hosting sporting events and city brand values, such as city image, satisfaction, and loyalty. While numerous studies have examined the impact of mega sporting events from various perspectives, a noticeable gap remains in the literature concerning residents’ perceptions of such events. The existing body of literature on this topic is sparse, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this study attempts to bridge this research gap by establishing the relationship between various factors crucial to the perceived event benefits of local residents in Beijing in 2022.

5.1. Influence of Perceived Benefits of the Beijing 2022 on City Image

The findings demonstrated that the perceived benefits of hosting mega sporting events and the economic, environmental, and tourism effects had a significantly positive impact on city image. Factors such as economy, environment, and tourism elements served as prerequisites for cultivating a positive city image among the host city’s residents.

The Beijing 2022 Games heavily depended on domestic tourism as a result of the COVID-19 situation and China’s border control measures. During Beijing 2022, the restrictions imposed by COVID-19 may have minimised the economic impact on local residents. However, Waitt [

84] applied the SET to his study of the Sydney 2000 Olympics, emphasising that exchange relationships are not temporally static. Therefore, as economic benefits were generated through the development of infrastructure and sports facilities before the event started, and with pandemic restrictions gradually easing during the middle of the event, it is reasonable to suggest that residents’ economic expectations of the Olympics evolved in response to these changing circumstances.

The Chinese government utilised the Winter Olympics as a platform to invest in the underdeveloped mountainous regions in Northern China, resulting in the establishment of several ski resorts and skating rinks. The main objectives of this investment were to boost local economies, generate employment opportunities, and enhance domestic tourism. The primary focus was to support the development of the winter sports industry in China for domestic benefits and investments [

85]. As indicated by a recent study, Beijing 2022 increased tourists’ interest in ice and snow tourism [

86], indicating a correlation between perceived economic, environmental, and tourism benefits.

In essence, locals perceived the event’s wider economic benefits as outweighing their personal costs. This suggests a linear relationship, where a greater perception of the expected benefits of mega sporting events corresponds to a more favourable perception of city image. This relationship is consistent with studies that asserted that sporting events have a positive impact on regional images [

87]. Liang et al. [

53] identified social, economic, and environmental benefits as significant factors affecting sustainable urban development. Perceived benefits positively impact sustainable development, whereas sustainable growth potential generates positive emotional responses from local residents towards their communities [

88].

This study supports the findings of Knott and Tinaz [

50], Matheson [

49], and Yang et al. [

52], indicating that the positive effects of hosting sporting events can enhance city image. Studies have also highlighted the crucial role of city image in defining a city’s characteristics and serving as a representation of its physical, economic, and cultural aspects [

14]. The concept of image similarity, which reflects the alignment between events and the city image, is known to enhance the existing image of a city by associating it with events [

89]. Such events can be facilitated through social and cultural exchange.

However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, perceived sociocultural effects did not positively contribute to city image, as hypothesised. This could be linked to the limited mobility of residents and the absence of cultural exchanges with visitors resulting from the strict COVID-19 protocols [

5]. In contrast to prior research findings [

52,

53], constrained interactions between locals and visitors did not result in significant sociocultural benefits. This highlights a notable deviation between previous research findings and those observed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Beijing 2022 may not have achieved all of its initially planned objectives, but it seems to have brought positive economic, environmental, and tourism perceptions to local residents. This can be interpreted as a result of China’s fundamental focus on objectives such as enhancing local economies, creating employment opportunities, and promoting domestic tourism, as well as supporting the development of the winter sports industry in China for domestic benefits and investments. These efforts resulted in a certain level of impact and achievement.

5.2. Influence of City Image of Beijing 2022 on City Satisfaction and Loyalty

The findings indicate that the perception of city image by residents in areas where the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics were to be held positively influenced city loyalty. This result is consistent with those of previous studies. Keller [

90] suggested that brand image significantly affected brand loyalty. Similarly, Boo and Busser [

91] argued that changes in the image of a host city for events could alter loyalty outcomes such as the intention to recommend. Furthermore, Kavaratzis and Ashworth [

92] reported that city image affected not only the impressions people have but also loyalty behaviours, such as revisits and word-of-mouth, aligning with the context of similar structural research. Specifically, Zenker and Rütter [

93] proposed that a resident-friendly city image positively impacted city loyalty and that the development and implementation of policies for citizens can enhance city loyalty.

Many nations have invested substantial resources into hosting various mega sporting events as a strategy to secure positive national and city images and foster loyalty from external participants and countries. However, this study emphasises that the city image perceived by local residents is also an important factor in securing city loyalty. This assertion is supported by a comparison with previous research. Specifically, this study provides additional statistical evidence for the mediating role of city satisfaction in the relationship between city image and loyalty. In other words, it confirms that a more effective causal relationship is established when positive city satisfaction is ensured as a prerequisite in the relationship between city image and loyalty as perceived by local residents.

Recognising the foundational role of residents’ perceptions of city satisfaction, Sirgy et al. [

94] highlighted the importance of positive feedback from residents. Lee et al. [

95] further underscored the significance of resident satisfaction with city living as a key variable affecting city loyalty. This demonstrates the importance of actively enhancing the city’s image through strategic development, effective communication with locals, and continued engagement before and after sporting events to position it as an attractive destination.

This finding reinforces the notion that city image directly affects visitors’ behavioural intentions and perceptions of a region [

96]. Chen and Gursoy [

97] emphasised the impact of regional images on consumer intentions such as revisitation and word-of-mouth recommendations, illustrating a direct link between image perception and visitor actions. Kaplanidou and Vogt [

98] found similar results in their study on spectators of the Athens 2004 Olympic Games, confirming the positive influence of the host area’s image on intentions to revisit and recommend the location to others, aligning with this study’s findings.

Kim and Petrick [

99] examined how host communities’ perception of events influences the overall city image and the willingness to recommend both events and the city as a tourist destination. The findings revealed a strong correlation between the overall city image and the inclination to recommend it as a tourist destination, highlighting residents’ role as advocates for their city. Ahlbrandt [

100] suggested that local residents’ positive perceptions of the city serve as the foundation for city satisfaction. These results support the hypothesis that city image positively affects city loyalty.

This study found that local residents believed that, even though the Olympics were held under restricted conditions owing to COVID-19, the event had a positive impact by enhancing the city’s image. This enhancement of city image contributes to urban satisfaction and loyalty, serving as a prerequisite for both. Ultimately, this can be explained through social exchange and expectancy-value theories, which consider three aspects: an individual’s belief in the feasibility of achieving specific expectations, the attractiveness of the outcomes, and the anticipation of achieving those outcomes. These theories can elucidate how residents perceive the economic, environmental, and sociocultural impacts of tourism development and other initiatives pursued by local authorities.

Therefore, host cities holding mega sporting events during future global pandemics should prioritise the implementation of urban projects from a domestic and sustainable perspective. This approach should concentrate on the economic, environmental, and tourism benefits for local communities. To achieve this, enhancing urban infrastructure, securing tourism assets, and expanding the sports industry from the viewpoint of local residents are essential for establishing a significant level of city loyalty within the community.

5.3. Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, the survey was conducted after Beijing 2022, and the COVID-19 pandemic had nearly ended. The results may have varied if the survey had been conducted before or during the event. Second, owing to the different measures adopted by each country against the pandemic, there are limitations to regional characteristics and their generalisability. Third, this study is limited to presenting results related to city satisfaction and loyalty of local residents and does not directly address the actual connection to residents’ support for city policies. Therefore, future research should include variables related to civic engagement to explore the benefits perceived by residents of mega-events locations.

6. Conclusion

This study discusses the unique challenges faced in hosting a mega sporting event, considering increased geopolitical tension, the impact of the global financial crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Hosting such events has become increasingly problematic owing to reduced domestic public support and concerns about COVID-19. This study examined the relationship between residents’ perceptions of hosting effects at the Beijing 2022 Olympics during COVID-19 and city image, satisfaction, and loyalty. Empirical verification was conducted using data collected through a survey, providing novel theoretical and empirical perspectives, particularly in the context of hosting Beijing 2022.

Participants were residents of Beijing and Zhangjiakou. SEM using AMOS 29.0 was employed for statistical processing to derive the results. A total of 868 questionnaires were included in the final analysis. The main findings are as follows. First, among the perceived benefits of the Beijing 2022 Olympic Games, economic, environmental, and tourism benefits were shown to have a positive impact on city image, but sociocultural benefits were found to have no positive impact on city image. Second, city image positively affected city satisfaction and loyalty. Third, city satisfaction positively affected city loyalty.

In conclusion, the findings revealed that local residents did not perceive any sociocultural effects due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite strict restrictions, economic, environmental, and tourism benefits contributed to enhancing city image as perceived by local residents, which positively affected city satisfaction. Local residents considered economic value both before and after the Games. Ultimately, this indicates that although Beijing did not exhibit sociocultural effects owing to its closed-loop system, the remaining perceived benefits support previous studies’ findings. This demonstrates that the benefits perceived through mega-events were a highly effective development strategy for local residents despite the constraints imposed by COVID-19. This indicates that these benefits are major factors that directly influence city image and contribute to increasing city satisfaction and loyalty. Thus, in exceptional circumstances such as COVID-19, to enhance the city loyalty of local residents, local governments must focus on the development of infrastructure and tourism resources from a long-term perspective, thereby contributing to the sustainable development of the city.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S.K.; methodology, S.K.; software, L.Y.; validation, S.K. and L.Y.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, S.K.; resources, L.Y.; data curation, L.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.K.; visualization, S.K.; supervision, S.K.; project administration, L.Y.; funding acquisition, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea, grant number (NRF-2021S1A5C2A02089866).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hamilton T. Premier League’s home edge has gone in pandemic era: The impact of fan-less games in England and Europe. ESPN. 2021 Feb 13. Available online: https://www.espn.com/soccer/story/_/id/37613907/impact-fan-less-games-england-europe (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Calcaterra C. Major League Basketball suspends baseball operations indefinitely. NBC Sport. 12 March 2022. Available online: https://www.nbcsports.com/mlb/news/major-league-baseball-to-suspend-baseball-operations-indefinitely (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- International Olympic Committee (IOC). Beijing 2022 spectator policy finalized. Lausanne: IOC; 17 January 2022. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/news/beijing-2022-spectator-policy-finalised (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Huo D.; Shen Y.; Zhou T.; Yu T.; Lyu R.; Tong Y., et al. Case study of the Beijing 2022 Olympic Winter Games: Implications for global mass gathering events amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2023, 11.

- Kilgore A. The closed loop eliminated covid, and joy, from the Olympics. The Washington Post. 18 February 2022. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/olympics/2022/02/18/beijing-olympics-closed-loop/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Nye Jr. J.S. Public diplomacy and soft power. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2008, 616(1), 94-109.

- Essex S.; Chalkley B. Olympic Games: catalyst of urban change. Leis. Stud. 1998, 17, 187-206. [CrossRef]

- Chalkley B.; Essex S. Urban development through hosting international events: a history of the Olympic Games. Plan. Perspect. 1999, 14(4), 369-394. [CrossRef]

- Paddison R. City marketing, image reconstruction and urban regeneration. Urban Stud. 1993, 30, 339-349. [CrossRef]

- Kearns G.; Philo C, editors. Selling places: the city as cultural capital - past and present. Oxford, UK: Pergamon; 1993.

- He G.; Yeerkenbieke G.; Baninla Y. Public participation and information disclosure for environmental sustainability of 2022 winter Olympics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7712. [CrossRef]

- Anholt S. Places: Identity, image and reputation. Springer; 2016.

- Morgan N.; Pritchard A. Tourism, promotion and power: Creating images, creating identities. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 1998.

- Lynch K. The image of the city. Cambridge: The MIT Press; 15 June 1964.

- Kavaratzis M. From city marketing to city branding: Towards a theoretical framework for developing city brands. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2004, 1, 58-73. [CrossRef]

- Tasci A.D.; Gartner W.C.; Cavusgil S.T. Measurement of destination brand bias using a quasi-experimental design. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28(6), 1529-1540. [CrossRef]

- Moreira P.; Iao C. A longitudinal study on the factors of destination image, destination attraction and destination loyalty. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 90-112.

- Jeong Y.; Kim S. A study of event quality, destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction, and destination loyalty among sport tourists. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 940-960.

- Kusumah E.P.; Wahyudin N. Sporting event quality: Destination image, tourist satisfaction, and destination loyalty. Event Manag. 2023. 28, 59-74. [CrossRef]

- Boonsiritomachai W.; Phonthanukitithaworn C. Residents’ support for sports events tourism development in Beach City: The Role of Community’s Participation and Tourism Impacts. SAGE Open 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Getz D. Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 403-428. [CrossRef]

- Lobo C.; Costa R.A.; Chim-Miki A.F. Events image from the host-city residents’ perceptions: impacts on the overall city image and visit recommend intention. Int. J. Tour. Cities. 2023, 9, 875-893. [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou K.; Karadakis K.; Gibson H.; Thapa B.; Walker M.; Geldenhuys S., et al. Quality of life, event impacts, and mega-event support among South African residents before and after the 2010 FIFA World Cup. J. Travel Res.2013, 52, 631-645. [CrossRef]

- Cleland J. Sports fandom in the risk society: Analysing perceptions and experiences of risk, security and terrorism at elite sports events. Sociol. Sport J. 2019, 36, 144-151.

- Boyle P.; Haggerty K.D. Planning for the worst: risk, uncertainty and the Olympic Games. Br. J. Sociol. 2012, 63, 241-259. [CrossRef]

- Klauser F. The exemplification of ‘fan zones’: Mediating mechanisms in the reproduction of best practices for security and branding at Euro 2008. Urban Stud. 2011, 48(15), 3202-3221.

- Brunet F. An economic analysis of the Barcelona’92 Olympic Games: resources, financing and impact. The Keys of success: the social, sporting, economic and communications impact of Barcelona 1995, 92, 250-285.

- Scherer J. Olympic villages and large-scale urban development: Crises of capitalism, deficits of democracy?. Sociol. 2011, 45, 782-797. [CrossRef]

- Wills, J. The Economic Impact of Hosting the Olympics. Investopedia. 12 March 2024. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/articles/markets-economy/092416/what-economic-impact-hosting-olympics.asp (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Parnell D.; Widdop P.; Bond A.; Wilson R. COVID-19, networks and sport. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 27, 78-84.

- Stott C.; West O.; Harrison M. A turning point, securitization, and policing in the context of Covid-19: Building a new social contract between state and nation?. Polic-J. Policy Practic. 2020, 14, 574-578. [CrossRef]

- Andereck K.L.; Vogt C.A. The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. J. Travel Res.2000, 39, 27-36.

- Gursoy D.; Kendall K.W. Hosting mega events: modelling locals’ support. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 603-623.

- Nunkoo R.; Gursoy D. Residents’ support for tourism: an identity perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 243-268.

- Zhou Y.; Ap J. Residents’ perceptions towards the impacts of the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games. J. Travel Res.2009, 48(1), 78-91.

- Nunkoo R.; Ramkissoon H. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964-988. [CrossRef]

- Andriotis K.; Vaughan R.D. Urban residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: The case of Crete. J. Travel Res.2003, 42, 172-185. [CrossRef]

- Rook K.S. Reciprocity of social exchange and social satisfaction among older women. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 145-154.

- Prayag G.; Hosany S.; Nunkoo R.; Alders T. London residents’ support for the 2012 Olympic Games: The mediating effect of overall attitude. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 29-40. [CrossRef]

- Vroom V. Work and motivation. New York: Wiley; 1964.

- Correia A.; Moital M. Antecedents and consequences of prestige motivation in Tourism: An expectancy-value motivation. In: Handbook of tourist behavior - theory and practice, Routledge; 2009. p. 34-50.

- Pekrun R. A social-cognitive, control-value theory of achievement emotions. In J. Heckhausen (Ed.), Motivational psychology of human development: Developing motivation and motivating development. Elsevier Science; 2000, p. 143-163.

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. The development of competence beliefs, expectancies for success, and achievement values from childhood through adolescence. Dev. Achiev. Motiv. 2002, 91-120.

- Atkinson J.W. Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychol. Rev. 1957, 64, 359. [CrossRef]

- Sparks B. Planning a wine tourism vacation? Factors that help to predict tourist behavioural intentions. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1180-1192. [CrossRef]

- Long P.T.; Perdue R.R. The economic impact of rural festivals and special events: Assessing the spatial distribution of expenditures. J. Travel Res.1990, 28, 10-14.

- Getz D. Event management and event tourism. New York: Cognizant Communication Corporation; 1997.

- Horne J.; Manzenreiter W. An introduction to the sociology of sports mega-events. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 54, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Matheson V. Assessing the infrastructure impact of mega-events in emerging economies. Economics Department Working Papers. 2012; Paper 8. Available online: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/econ_working_papers/8.

- Knott B.; Tinaz C. The legacy of sport events for emerging nations. Front. Sports Act. Living2022, 4, 926334. [CrossRef]

- Thomson A.; Cuskelly G.; Toohey K.; Kennelly M.; Burton P.; Fredline L. Sport event legacy: A systematic quantitative review of literature. Sport Manag. Rev.2019, 22, 295-321. [CrossRef]

- Yang J.; Zeng X.; Gu Y. Local residents’ perceptions of the impact of 2010 EXPO. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2010, 11, 161-175.

- Liang Y.W.; Wang C.H.; Tsaur S.H.; Yen C.H.; Tu J.H. Mega-event and urban sustainable development. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2016, 7, 152-171.

- Bandyopadhyay R.; Morais D. Representative dissonance: India’s self and western image. Ann. Tour. Res.. 2005, 32, 1006-1021.

- Lindblom J.W.; Legg E.; Vogt C.A. Diving into a new era: The role of an international sport event in fostering peace in a post-conflict city. J. Sport Dev. 2022, 10, 72-88.

- Luong T.B. Destination image and loyalty: Examining satisfaction, place attachment, and perceived safety. J. Policy Res. Tour Leis. Events. 2023, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Song Z.; Su X.; Li L. The indirect effects of destination image on destination loyalty intention through tourist satisfaction and perceived value: The bootstrap approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 386-409.

- Astuti W.T. The influence of brand image, brand love, and brand trust on brand loyalty in local coffee shop brand names. J. Res. Soc. Sci. Econ. Manag. 2023, 2, 3021-3036. [CrossRef]

- Zenker S.; Martin N. Measuring success in place marketing and branding. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2011, 7, 32-41. [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves J.; Ferrando M.G. Public opinion, national integration and national identity in Spain: The case of the Barcelona Olympic Games. Nations Natl. 1997, 3, 65-87. [CrossRef]

- Duan Y.; Wu J. Sport tourist perceptions of destination image and revisit intentions: An adaption of Mehrabian-Russell’s environmental psychology model. Heliyon 2024, 10, E31810.

- Oshimi D.; Harada M. The effects of city image, event fit, and word-of-mouth intention towards the host city of an international sporting event. IJSMaRT 2016, 24, 76-96.

- Aleshinloye K.D.; Woosnam K.M.; Joo D. The influence of place attachment and emotional solidarity on residents’ involvement in tourism: perspectives from Orlando, Florida. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights. 2024, 7, 914-931. [CrossRef]

- Eusébio C.; Vieira A.L.; Lima S. Place attachment, host–tourist interactions, and residents’ attitudes towards tourism development: The case of Boa Vista Island in Cape Verde. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 890-909.

- Romero-Subia J.F.; Jimber-del Rio J.A.; Ochoa-Rico M.S.; Vergara-Romero A. Analysis of citizen satisfaction in municipal services. Economies 2022, 10, 225. [CrossRef]

- Wang H.; Yang Y.; He W. Does value lead to loyalty? Exploring the important role of the tourist–destination relationship. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 136.

- Ritchie B.W.; Shipway R.; Cleeve B. Resident perceptions of mega-sporting events: A non-host city perspective of the 2012 London Olympic Games. J. Sport Tour. 2009, 14, 143-167. [CrossRef]

- Ko E.K.; Kim K.H.; Kim S.H.; Li G.; Zou P.; Zhang H. The Relationship among Country of Origin, Brand Equity and Brand Loyalty: Comparison among USA, China and Korea. J. Glob. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 19, 47-58.

- Cronbach L.J. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297-334. [CrossRef]

- Andereck K.L.; Valentine K.M.; Knopf R.C.; Vogt C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056-1076. [CrossRef]

- Ap J.; Crompton J.L. Developing and testing a tourism impact scale. J. Travel Res.1998, 37, 120-130.

- Chang M.X.; Choong Y.O.; Ng L.P.; Seow A.N. The importance of support for sport tourism development among local residents: the mediating role of the perceived impacts of sport tourism. Leis. Stud. 2022, 41, 420-436.

- Duan Y.; Mastromartino B.; Zhang J.J.; Liu B. How do perceptions of non-mega sport events impact quality of life and support for the event among local residents?. Sport Soc..2020, 23, 1841-1860.

- Artuğer S.; Çetinsöz B.C.; Kılıç I. The effect of destination image on destination loyalty: An application in Alanya. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 124-136.

- Anderson J.C.; Gerbing D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411.

- Bagozzi R.P.; Yi Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74-94.

- Nunnally J.C. Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978.

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, Ullman JB. Using multivariate statistics (6th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson; 2013. p. 497-516.

- Fornell C.; Larcker D.F. Evaluation structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39-50.

- Browne M.W.; Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230-258. [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Cohen J.; Cohen P. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Taylor & Francis; 1983.

- Alwin D.F.; Hauser R.M. The decomposition of effects in path analysis. Am. Sociol. Rev.1975, 40, 37-47. [CrossRef]

- Waitt G. Social impacts of the Sydney Olympics. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 194-215. [CrossRef]

- Harcourt T. The Economic Impact of Hosting the Olympics. UTS. 2 February 2022. Available online: https://www.uts.edu.au/news/culture-sport/economics-beijing-winter-olympics-2022 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Liu S.; Guo Q. Image perception of ice and snow tourism in China and the impact of the Winter Olympics. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0287530.

- Cronin J.J. Jr; Taylor S.A. Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension. J. Mark 1992, 56, 55-68.

- Gursoy D.; Yolal M.; Ribeiro M.A.; Panosso Netto A. Impact of trust on local residents’ mega-event perceptions and their support. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 393-406. [CrossRef]

- Gwinner K.P.; Eaton J. Building brand image through event sponsorship: The role of image transfer. J. Advert. 1999, 28, 47-57. [CrossRef]

- Keller K.L. Strategic branding management: building, measuring, and managing brand equity. Prentice Hall; 2003.

- Boo S.; Busser J.A. Impact analysis of a tourism festival on tourists destination images. Event Manag. 2005, 9, 223-237.

- Kavaratzis M.; Ashworth G.J. City branding: An effective assertion of identity or a transitory marketing trick?. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2006, 2, 183-194. [CrossRef]

- Zenker S.; Rütter N. Is satisfaction the key? The role of citizen satisfaction, place attachment and place brand attitude on positive citizenship behavior. Cities 2014, 38, 11-17. [CrossRef]

- Sirgy M.J.; Gao T.; Young R.F. How does residents’ satisfaction with community services influence quality of life (QOL) outcomes?. Appl. Res. Qual. Life. 2000, 5, 159-172. [CrossRef]

- Lee S.W.; Seow C.W.; Xue K. Residents’ sustainable city evaluation, satisfaction and loyalty: Integrating importance-performance analysis and structural equation modelling. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6766.

- Chen C.F.; Tsai D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions?. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115-1122.

- Chen J.S.; Gursoy D. An investigation of tourists’ destination loyalty and preferences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 13, 79-85.

- Kaplanidou K.; Vogt C. The interrelationship between sport event and destination image and sport tourists’ behaviors. J. Sport Tour. 2007, 12, 183-206.

- Kim S.; Petrick J.F. Residents’ perception on impacts of the FIFA 2002 World Cup: The case of Seoul as a host city. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 25-38.

- Ahlbrandt R. Neighborhoods, people, and community. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).