1. Introduction

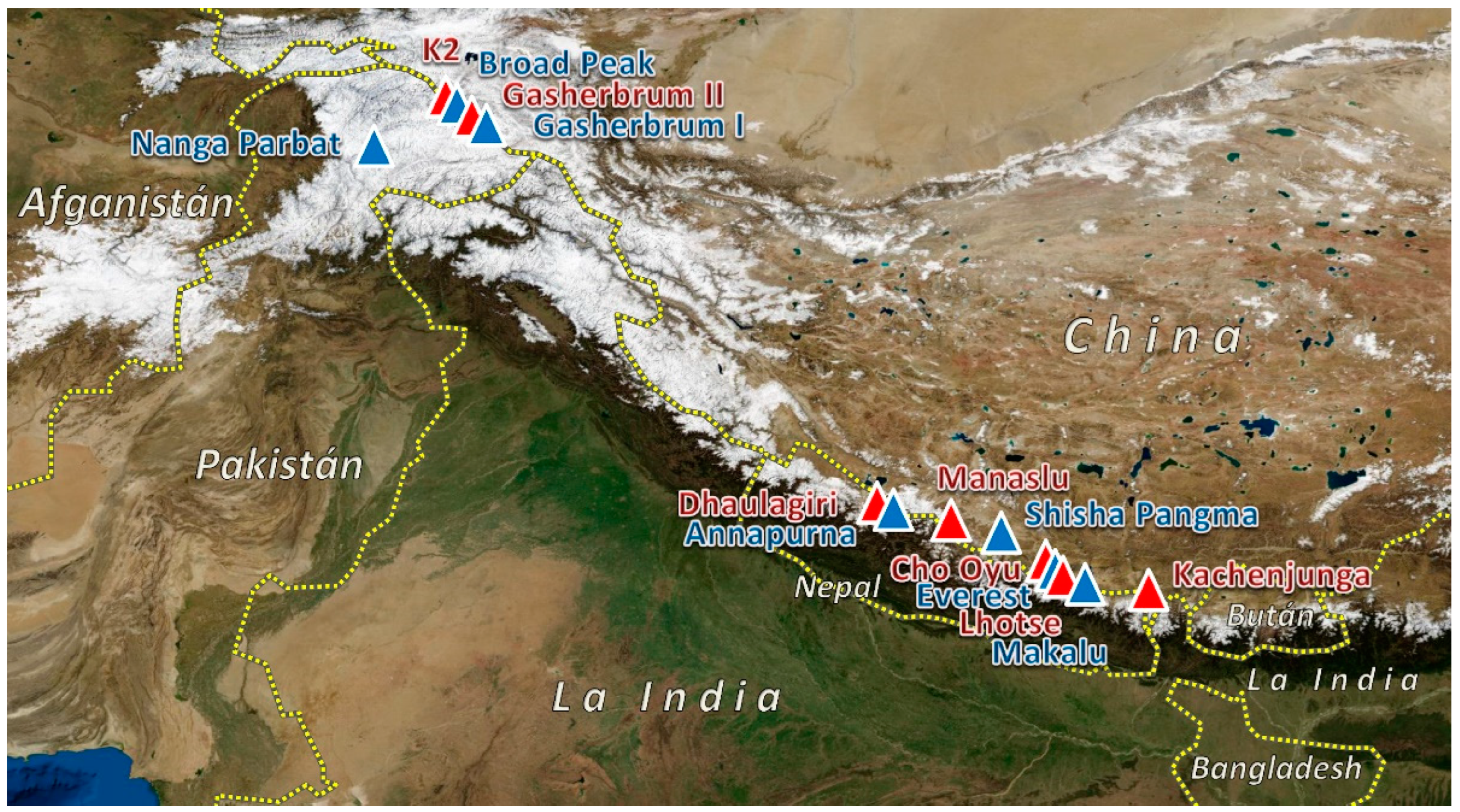

Uninhabitable and hostile to humans, high altitude ecosystems (above 8000 m) have been protected from human influence until very recently. In 1895, the first recorded attempt to climb an 8000 m peak was both fatal and unsuccessful as the British climber Albert Mummery had no knowledge of the low oxygen concentration and low pressure at high-altitude (Horrell, 2015). In the 1950s, the first successful ascents of 8000m mountains were achieved. The first by French climbers Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal summiting Annapurna I. did not make headline news outside of the mountaineering community. The 1953 Everest/Sagarmatha/Chomolungma ascent by Tenzing Norgay of Nepal, and Edmund Hillary of New Zealand was next and the most famous ascent. Since then, barriers have been continuously broken, and now over 40 mountaineers have summited all fourteen 8000m peaks shown in

Figure 1).

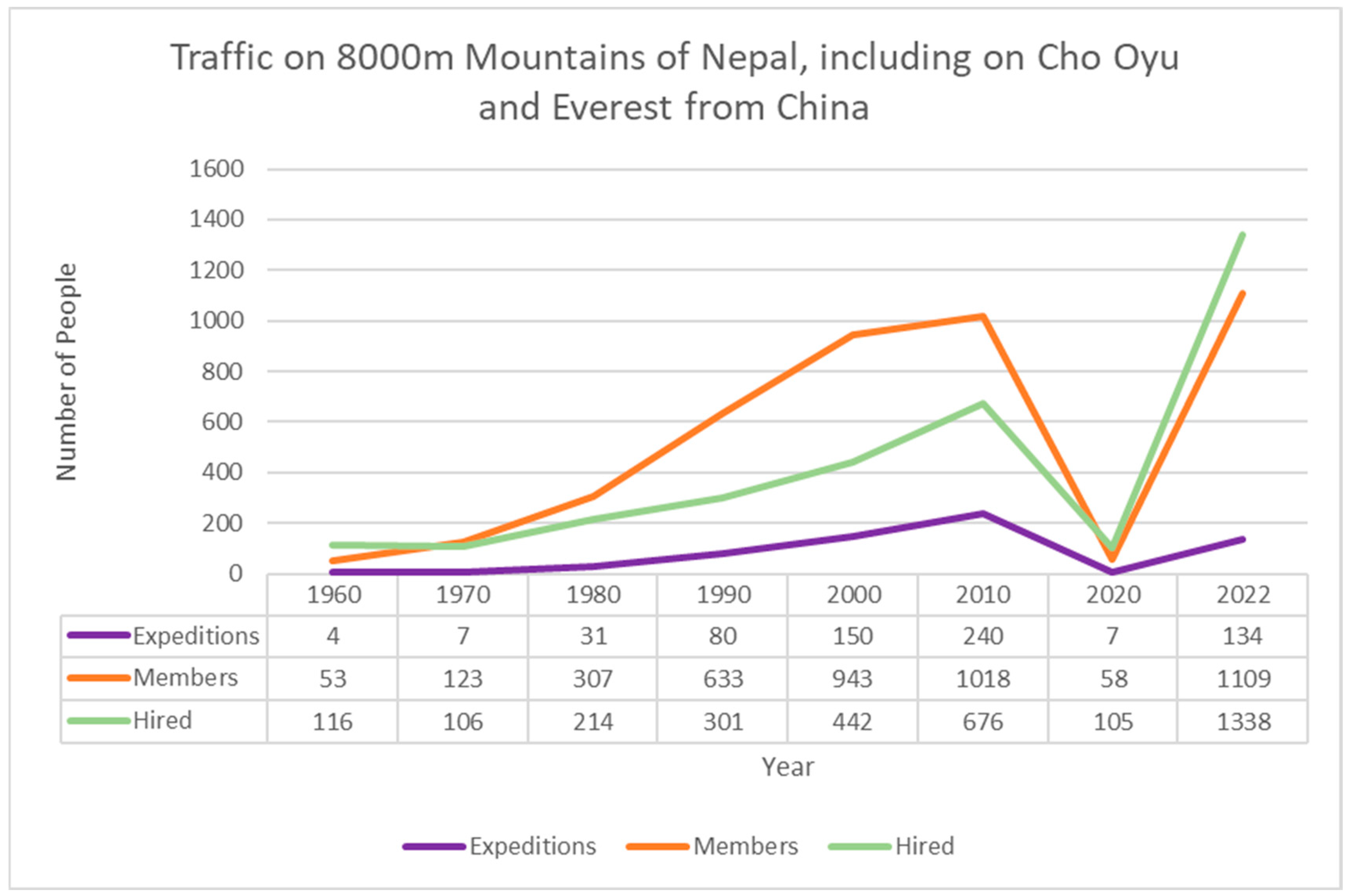

In under 100 years, the sport has gone from a few participants to thousands of people visiting these mountains. The abrupt increase of visitors to Nepal and Everest, specifically for high-altitude mountaineering is evident in

Figure 2.

As with the early adventurers, many mountaineers come from Europe, North America or Oceania, whilst the fourteen 8000 m mountains in the world are part of the Himalaya and Korakoram mountain ranges and fall across Nepal, Pakistan, and Tibet as shown in

Figure 3. Therefore, most mountaineers travel distances from 6,000 to over 12,000 km. In addition, mountaineers often have time constraints, and thus take many internal flights instead of trekking, or using other land-based transport. In 2019, there were 2,153,245 international flight movements in Nepal, in addition to 94,640 domestic flights (Nepal Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation, 2020). From 2011 to 2019, international flight movement in and out of Nepal has risen 42% and is likely to continue to rise. Whilst not exclusively tourist flights, tourism accounts for a significant proportion. Particularly alarming, since calculations accounting for all emissions demonstrate that the ‘warming footprint’ of aviation is twice the carbon footprint; therefore, earlier research underestimated the contribution of air travel to climate change (Klöwer et al. 2021). Moreover, the emission of black carbon particulate matter has detrimental impacts to human health and the natural environment from local to global scales (Brewer, 2019; CCAC, 2016).

An increase in international adventurers directly conflicts with calls to reduce air travel due to the climate crisis. The earliest impacts of climate change include those to the delicate ecosystems of high-altitude mountainous regions (Beniston, 2003 and Palomo, 2017). Moreover, reduced snow and ice cover from permafrost degradation increases the risk of avalanches creating an even more perilous sport (Haeberli and Whiteman, 2015). The sport already takes place in the so-called ‘death zone’, one of the most inhospitable places on earth, where human life cannot be sustained (Huey and Eguskitza, 2001). Therefore, a feedback occurs as mountaineers’ travel contributes to climate change, while climate change creates greater risks for high altitude mountaineers. The consequences of the risk to life and potential decrease in the ability to act sustainably along with the consequences of a substantial increase in the number of individuals on the mountains have received very little research attention.

Additionally, a complex relationship exists between mountaineers, climate change and the consequences to the social, economic and environmental sustainability of local communities. The ice reserves of the Himalayan glaciers alone constitute a volume of 3,735 km3 (Liu and Rasul, 2007) so any temperature increases and subsequent melting of the ice reserves will have severe and dramatic implications on nearby communities. Moreover, some 500 million inhabitants rely on the Himalayan ice reserves as a water source (IPCC, 2007). Palomo (2017) expressed concern about the future security of high mountain communities, given the likelihood of increased natural hazards such as landslides, glacial lake outburst floods and extreme weather events. Most of the research on the Himalaya and Korakoram focuses on environmental science (Wiltshire, 2014; Azam et al., 2021; Hasson, 2016), with little attention given to the equally important social and economic sustainability. Based on environmental impacts alone, one might suggest discontinuing the sport of high-altitude mountaineering. However, for those living in high-mountain communities this would further reduce the already limited employment options thereby decreasing their current low adaptive capacity (Maraseni, 2012).

The focus of the research is primarily on the perspectives and experiences of high-altitude mountaineers as their activities create this sustainability dilemma. This paper emphasises the complex relationship between climate change, risk and sustainable behaviour, whilst also drawing attention to the potential trade-offs for the environmental, social and the economic sustainability of local communities. This research has exposed a plethora of sustainability issues and a large attitude behaviour gap regarding sustainability in 8000m mountaineering. The results also revealed specific solutions to sustainability issues identified, these include portable waste management solutions, carbon offsetting, investment in the local area and clean-up operations.

2. Literature Review

Despite this history and expansive growth, only a few related studies have been conducted on high-altitude sport. Musa, Hall and Higham, 2004 and Basnet, 1993 focussed on the sustainability of eco-tourism in high-altitude trekking in the Sagarmatha (Everest) National Park. These studies have limited comparability as trekking does not present the same risk-behaviour scenario. Bateman (2019) and Taylor and Komissarov (2019) (The authors intended that their work be disseminated using knowledge exchange articles and research reports, rather than traditional academic journals (S. Taylor, 2021, personal communication, 14th November 2021). Taylor and Komissarov’s approach was intended to have practical applications, and did lead to a subsequent clean-up operation, whereby 6.5 tonnes of waste was removed based upon the study’s recommendation (S. Taylor, 2021, personal communication, 14th November 2021).) provide more comparable studies to this research; however neither paper has been peer-reviewed. While not specific to high-altitude mountaineering, the focus on “Identifying and Addressing the Environmental Impacts of Mountaineering” (Bateman, 2019, p52) provides details helpful in guiding this research and Taylor and Komissarov (2019) demonstrate the value of context-specific research in their study of high-altitude mountaineering at Lenin Peak in Kyrgyzstan.

Bateman (2019, p54) draws attention to the challenges mountaineering can bring in terms of “carbon emissions from travel, improper waste disposal, including human waste, erosion, and infrastructure development”, but at the same time limits sustainability to a purely environmental concept. Bateman (2019) focuses on the issue of human waste, noting that it poses numerous issues, including lack of decomposition of faeces at high altitude, a high prevalence of diarrhoea amongst high-altitude mountaineers, and disposal of waste in glaciers contaminating water sources. High prevalence of diarrhoea presents sustainability issues in several ways, loss of fluids due to diarrhoea can exacerbate the risk of AMS, acute mountain sickness, (Anand, Sashindran and Mohan, 2006) and this in turn increases the likelihood of rescue evacuations by air (Dawadi, Pandey and Pradhan, 2020). Furthermore, mountaineers using the top layer of snow as their water source can cause gastrointestinal infections and diarrhoea, and as a result a vicious cycle ensues (Bateman, 2019).

Solutions offered by Bateman (2019) include the raising of awareness, carbon offsetting, encouraging commercial outfitters to pursue sustainability, developing the sustainability advising role of mountaineering associations and the role of governments as environmental stewards particularly via permits and fees, as well as human waste management.

Whereas Bateman (2019) provides generalised issues and solutions, Taylor and Komissarov (2019) conducted a highly detailed and location specific study, thus providing a successful framework for a critical assessment of issues in high-altitude mountaineering. Taylor and Komissarov (2019) evaluated the sustainability conditions on each camp of Lenin Peak, as well as the specific hazards. This overview “helped establish the basis for ensuring sustainable tourism” (Taylor and Komissarov, 2019, p35). Interestingly, Taylor and Komissarov (2019) identified the threat to sustainability posed by safety issues; they sought to indirectly improve the sustainability situation by increasing safety measures. It must however be noted that the specific safety issues on Lenin Peak are greatly amplified on the 8000m mountains. For comparison, the summit of Lenin Peak is 7,134m (Britannica, 2021), whereas the mountains studied in this paper range from 8,027m to 8,848m. The effective oxygen percentage on the summit of Lenin Peak is around 8.6%, whereas on the summit of Everest (8839m) it is only 6.9% (Wild Safe, 2022). By contrast the oxygen percentage at sea level is 20.9% (Mile High Training, 2022).

There is undoubtedly a significant research gap regarding sustainability in 8000m mountaineering and how the high risks of 8000m mountaineering affect human capacity to act sustainably. Whilst this research has context specific practical outcomes for high altitude mountaineering, it also contributes to wider debates related to sustainability tradeoffs and the sustainability of outdoor sports and travel. The next sections detail the wider literature related to these debates.

2.1 Sustainable Development of Tourism

Sustainable development is often referred to as a single, united principle, but in practice it is often a paradox (Latouche, 2003). Tarlock (2001) illustrated the paradox via his critique of the Brundtland Commission’s claim of symbiosis between development and environmental protection; so called ‘sustainable development’. There are countless examples of environmental sustainability resulting in trade-offs with economic and social development (Sandker, Ruiz-Perez, and Campbell, 2012; McShane et al., 2011; Hirsch, Brosius, and Gagnon, 2013). The case of high mountain areas of the Korakoram and Himalaya ranges are no exception. High-altitude mountaineering undoubtedly creates and exacerbates environmental issues but brings wide economic and social benefits. Tourism was the fourth largest industry by employment in Nepal in 2019 (Kathmandu Post, 2021). Mountain tourism alone generated $724million (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2020). The increase in tourism has been beneficial in helping Nepal move from a Least Economically Developed Country to a Developing Country (UNDP, 2019). Mountain tourism in Nepal has been particularly beneficial for the Sherpa communities. In 2020 a Sherpa Sirdar (lead mountain guide) was able to earn between $10,000 to $25,000 a year (Arnette, 2022) which is far greater than the average salary in Nepal of $3,204 (BDEX, 2022). This has however undoubtedly come at an environmental cost to these areas. Apollo and Andreychouk (2020) claim that mountaineering always has a positive impact on populated areas, but above populated areas, the impact is almost always negative.

2.2. Outdoor Sports and Sustainability

Outdoor sports and sustainability also have a paradoxical relationship. Outdoor recreationalists rely on nature to provide intrinsic value, but these outdoor activities frequently degrade the resources on which they depend. There is widespread evidence of this, ranging from large numbers of hikers degrading footpaths in national parks (Fidelus-Orzechowska et al., 2021), to reduced plant cover and species richness as a result of rock climbing (Lorite et al., 2017). Fortunately, people engaging in outdoor sports frequently feel compelled to participate in efforts to ensure sustainability (Ministry of Environment, 2016; Porter and Bright, 2003; Høyem, 2020, Ives et al., 2018). However, Høyem (2020) claims that outdoor recreationists tend to be more concerned about environmental problems in areas they frequent, rather than wider environmental challenges.

2.3. Last Chance Tourism

The Himalayas, and to a lesser extent the Korakoram have long been revered as the epitome of beauty in nature. The 8000m peaks have fragile weather systems, and therefore, are especially vulnerable to climate change (Wiltshire, 2014). Tourist demand to these places can increase when tourists act on their desire to experience these places before they are irreversibly changed, a phenomenon termed ‘last chance tourism’ (Dawson et al., 2011). Tourists often accelerate the rate of change, due to the frequent use of carbon intensive, long-distance travel (Dawson et al., 2011), and applying additional pressures to local infrastructure and causing physical erosion of landscapes (Clark and Johnston, 2017)). Considerable research supports Dawson et al. (2011) claim that human travel decisions centre around individual self-interest, rather than long term considerations for the planet and people (Hindley and Font, 2014; Fennell, 2019; Canavan, 2017). The Himalaya and Korakoram ranges have reached a critical stage where rapid deterioration must be prevented through management of the issues. Unfortunately, as Margolis (2006) aptly points out, people often only act when the situation becomes increasingly dire. Dawson et al.’s (2011) theory of ‘last chance tourism’ demonstrates the importance of this study at this critical stage.

In summary, the paradox of sustainable development, the relationship between outdoor sports and sustainability, and last chance tourism illustrate:

Why sustainability cannot be easily defined.

Why there are sustainability issues with high altitude mountaineering.

Why research into the sustainability of high-altitude mountaineering is increasingly important.

Therefore this research aims to identify the sustainability values and behaviour of high altitude mountaineers within the context of the high risk environment of their sport by addressing the following research objectives:

Assess what sustainability means to climbers in the high-altitude mountaineering context.

Examine sustainability issues associated with high-altitude mountaineering on 8000 m mountains.

Investigate the potential relationship between risk to human life and capacity to act sustainably on the mountains.

Explore existing and potential solutions to the complex sustainability issues presented by death zone mountaineering.

3. Methods

Pragmatic and epistemological reasoning dictated the research approach. Qualitative research was selected for this study as it is commonly used where there is little existing research, a new perspective is being considered, or current knowledge is fragmented (Kyngäs, 2020). Defining the target population as high-altitude mountaineers means the participant pool was both very small relative to the general population and globally dispersed. The primary concern was to gather a range of perspectives that reflected the international diversity of the high-altitude mountaineering ‘community’ and not to be concerned with representativeness of the sample. This study used an inductive qualitative approach involving a small number of participants due to these considerations (Reeves, Kuper and Hodges, 2008). Use of a questionnaire was a pragmatic decision due to the difficulty with conducting only interviews with members of the target population. The questionnaires consisted of open-ended questions generating qualitative data similar to an interview.

3.1. Participant Outreach

Participant recruitment was also challenging due to the frequent expeditions of mountaineers, involving long periods with limited internet connection. Therefore, a convenience purposive sampling hybrid was deemed the most feasible strategy for both the pilot and main questionnaire (Andrade, 2021). In total approximately 100 messages were sent to expedition companies, mountaineers’ personal social media accounts, Facebook mountain groups, mountaineers’ websites, and Reddit mountaineering threads. From the messages sent, 11 pilot survey responses and 16 main survey responses were collected. One participant withdrew early due to their lack of confidence in the English language. Language skills may have deterred other potential participants, thus reducing the pool of available participants.

3.2. Pilot Questionnaire

A pilot survey was conducted to assess how well participants would engage with the survey questions and whether the questions were suitable in eliciting responses that addressed the research objectives.

Eleven mountaineers responded to the pilot survey. The sample pool was high-altitude mountaineers but was not limited to only those with experience of 8000m peaks. This sample was selected to avoid using exclusively the same pool as the main survey but ensured that the questions were still applicable and therefore achieving their desired purpose of testing the suitability of the survey.

The pilot questionnaire consisted of three parts: participant informed consent, the main body, and background information. The main body consisted of eight open-ended questions, and a snowball sampling question, asking if participants knew any high-altitude mountaineers who would be interested. The eleven responses received provided sufficient data to interpret the effectiveness of the questionnaire, since saturation was reached at this point as additional responses did not bring new insights (Fusch and Ness, 2015).

On the basis of the pilot survey, the following changes were made to the main questionnaire: one question was removed (Question 7,

Appendix A) as it received repetitious answers duplicating the subsequent question (Question 8,

Appendix A). One additional open-ended question was added to determine existing sustainability measures that participants thought were particularly successful (Question 9,

Appendix B). Participants answered yes/no to a question that was intended to elicit a longer response, and so “please explain your answer” was added (Question 6,

Appendix B). Two additional background questions were also added in order to explore whether nationality impacted perception of the sustainability situation and to understand any variation across different 8000m mountains (Questions 13 and 18,

Appendix B). Both the pilot questionnaire and main questionnaire were organised into an order that established sustainability and the core of the project, and then progressed onto more personal insights and experiences.

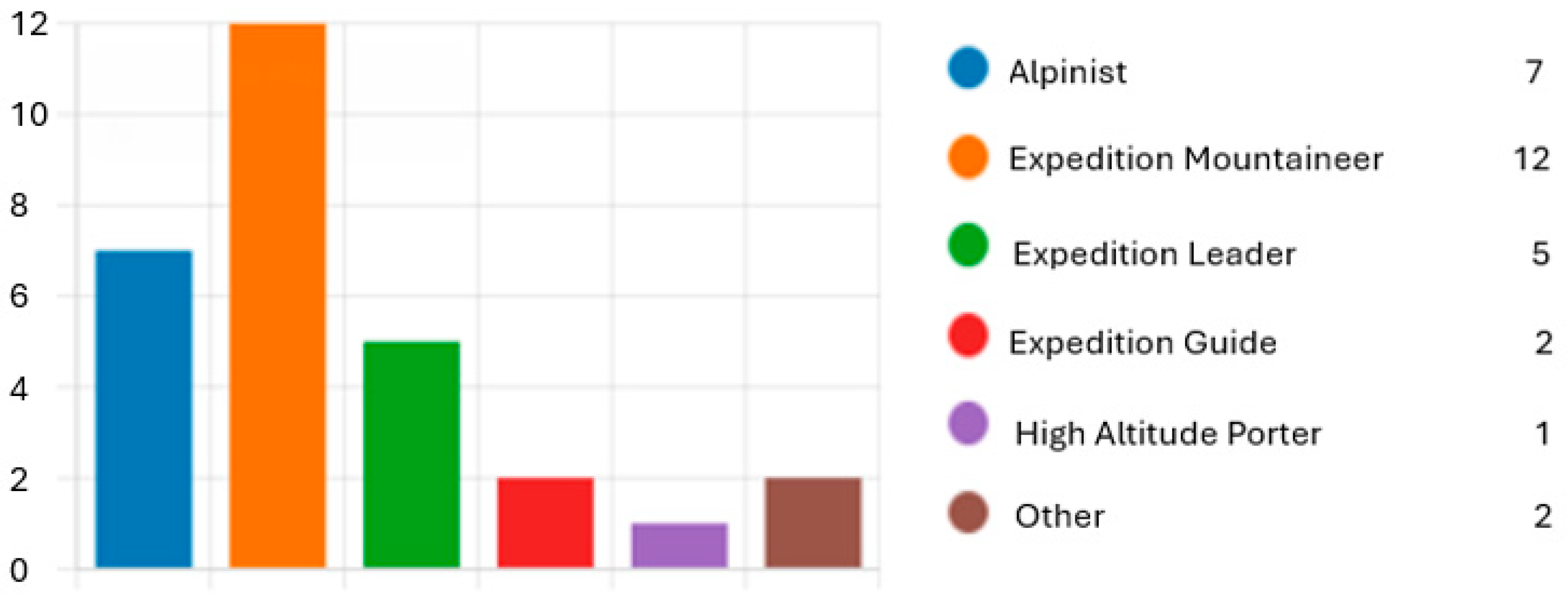

3.3. Main Questionnaire

The final survey received sixteen responses from mountaineers with experience of 8000m peaks. At this point theoretical saturation was reached, since additional responses were producing repetitive data (Saunders et al., 2018). It was significantly more difficult to find participants for the main survey than the pilot, due to the narrow sampling criteria of people with experience of 8000m mountaineering. The sixteen participants were from a variety of mountaineering roles (see

Figure 4).

The questionnaire was again comprised of three parts: participant informed consent, the main body, and background information; largely replicating the framework of the pilot study. The questionnaire began by focusing on the meaning of sustainability as this established the primacy of the concept (Questions 3 and 4,

Appendix B). The survey structure was informed by the serial position effect and primacy theory, which dictate that the first question receives the most attention (Feigenbaum and Simon, 1962). The first questions of the main body (Questions 4,5 and 6,

Appendix B) were ordered with the intention of constructing a timeline of sustainability in the high-altitude mountaineering context, as there is limited existing data on the topic. This was followed by questions requiring more judgement and personal insight, such as “the greatest challenges” and possible solutions. The main body of the questionnaire concluded with a question on how sustainability could be improved. This was again due to the serial position effect, whereby emphasis is placed on the last question (Neath, 1993). A limitation of the sequence of questions was however the risk of priming due to the question on the effect of commercialisation (Lundh and Czyzykow-Czarnocka, 2001). By mentioning commercialisation there was a risk of influencing the responses to subsequent questions such as “what are the greatest sustainability challenges”. The commercialisation question did however receive some useful responses, and it was phrased neutrally, and so there remains sufficient justification for its inclusion.

3.4. Interviews

A total of five semi-structured individual interviews were conducted on Microsoft Teams, and were recorded and auto-transcribed using Microsoft Teams. These interviews were with questionnaire participants who had provided their details in order to arrange a follow-up interview.

Interviews were selected for this study as comparable studies (Taylor and Komissarov, 2019) successfully answered their research objectives through interviews with mountaineers. Individual interviews were selected over focus groups due to the personality traits of high-altitude mountaineers, namely assertiveness and extraversion (Crust, 2020). The decision to conduct individual interviews was therefore deemed to be more successful in eliciting deep, personal responses in this study. Additionally, individual interviews offer valuable opportunities for rapport building (Barriball and While, 1994), which in this context could provide enhancements in data collection. Semi-structured interviews were selected as they are well suited to small-scale research and allow for flexibility to explore any interesting themes that may arise (Drever, 1995).

The interviews consisted of a total of seven questions (see

Appendix C), with additional unscripted questions added as appropriate. The interviews were intended to take between thirty and forty minutes, allowing for significant data collection and thorough understanding of participants’ perspectives (Mears, 2012). In general participants of both the surveys and the interviews were enthusiastic about participating in the project and gave good feedback on the research topic, and the importance of improving understanding of sustainability in the sport and in the region.

3.5. Data Analysis

Data analysis occurred after all the interviews had taken place, and their transcripts had been cleaned. Constructivist grounded theory informed this qualitative data analysis as there was little existing research on the topic, an open and exploratory method of analysis was well suited to the study (Charmaz, 2017). Coding consisted of three distinct phases: open, axial and selective coding (Strauss and Corbin, 1997; Walker and Myrick, 2006; Danaeifard and Emami, 2007).

Within grounded theory, this study used a bottom-up approach of inductive line-by-line coding. Line-by-line coding was well suited to a small dataset and allowed depth, without being unfeasibly labour intensive (Timonen, Foley and Conlon, 2018). This approach began by reading the transcripts and selecting small sections of data which were then labelled into codes, using an open coding. This was followed by axial coding, which sought relationships and broader categories within the data. Finally, selective coding was conducted, which discovered one overarching theme that connected to almost all codes (Saldaña, 2021). Analysing all the data together had numerous benefits, especially at the selective coding stage. The overarching theme of ‘leave no trace’ was more apparent given a review of the entire dataset than it might have been with more periodical analysis. The choice of inductive line-by-line coding provided an intimate connection between the data and the researcher which was particularly useful in the context of this study, where there was little existing research.

The codes were narrowed into 12 broader categories through axial coding, and these categories were used as subsections in response to each research objective. Finally, the codes and categories clearly highlighted the one overarching theme within the data of ‘leave no trace’.

3.6. Ethics

This study strictly adhered to ethical guidelines in data collection. At the core of ethical research is informed consent. The participant informed consent formed the first section of the questionnaires, via an information page and then two questions confirming that participants both read and agreed to the information provided (Questions 1 and 2,

Appendix A and Appendix B). In the interviews, information was read to the participants regarding anonymity and recording consent, which were granted before the interviews commenced. All participants in the questionnaire and the interviews were guaranteed anonymity, this was principally for ease of ethics approval, but when participants later disclosed sensitive information such as illegal activities, this proved to be advantageous. In addition, every effort was made to ensure neutrality and prevent leading questions, in both the questionnaires and the interviews. This study complies with the General Data Protection Regulations of 2018 and does not divulge any personal information without prior consent. Finally, it should be noted that high-altitude mountaineering is a very high-risk sport, as a result, any study engaging with the discipline poses ethical questions. This study, however, draws upon previous experiences and does not encourage participants to engage in further high-risk behaviour, therefore attempting to stifle any ethical implications.

4. Results

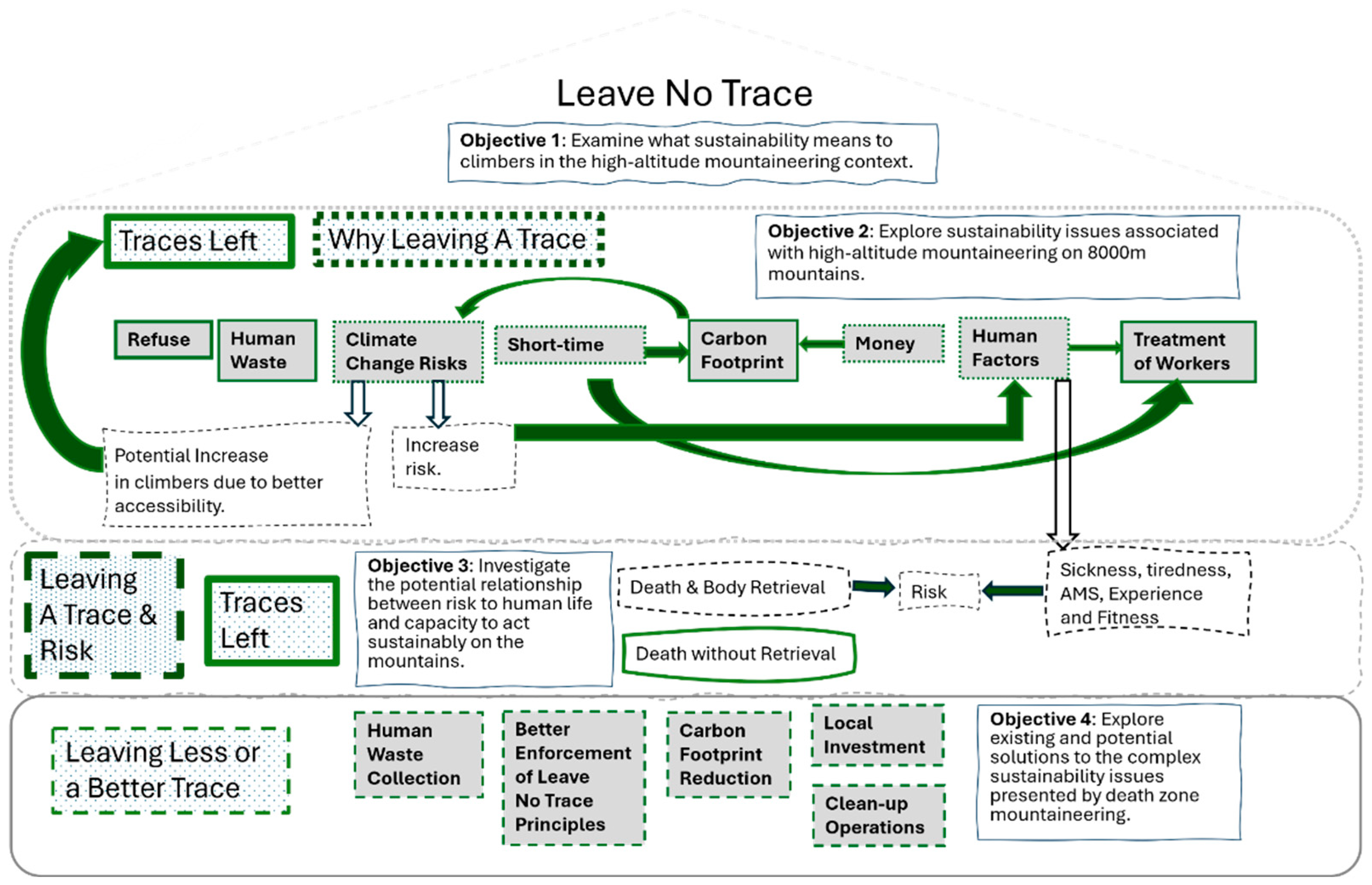

The results of open coding revealed over 50 codes (see appendix D). This was later narrowed to 12 broader categories, through axial coding, and finally into one overarching theme of ‘leave no trace’ through selective coding. The overarching theme encompassed all codes and corresponded to the research objectives in the following ways:

Examine what sustainability means to climbers in the high-altitude mountaineering context: almost all participants strongly associated sustainability with the principles of ‘leave no trace’(4.1).

Explore sustainability issues associated with high-altitude mountaineering on 8000m mountains: the issues raised by participants were contraventions of ‘leave no trace’ principles along with explanations as to why ‘leave no trace’ principles were not followed (4.2).

Investigate the potential relationship between risk to human life and capacity to act sustainably on the mountains: most participants viewed tiredness, sickness, and hazardous conditions on the mountains as contributing to lack of mental capacity to act sustainably and follow ‘leave no trace’ principles (4.3).

Explore existing and potential solutions to the complex sustainability issues presented by death zone mountaineering: there were mentions of Vinson, Denali and Aconcagua as examples of more successful sustainability measures in a similar context. Participants also suggested increasing environmental regulation and mandatory sustainability responsibility for expedition firms to ‘leave no trace’. Local investment provides an example of ‘leaving a better trace’ (4.4).

The following results section will be structured according to the research objectives and within research objectives structured according to the broader categories.

Figure 5 provides a graphic representation of the results with each research objective.

4.1. Objective 1: Examine what sustainability means to climbers in the high-altitude mountaineering context

Sustainability is often academically perceived as three pillars: environmental, social and economic (Scott, 2003). In this study, participants tended to focus more on the environmental aspect of sustainability, concentrating on principles such as “leave no trace” (participant from France) and “limit[ing] carbon footprint” (participant from the Netherlands). The focus on sustainability as “leave no trace” was particularly consistent amongst European and North American participants, this is perhaps due to framing in Western media. As this was the first question in the survey, and the project title was worded neutrally, it is highly unlikely that the study itself elicited any framing. Several participants interpreted sustainability as ensuring that the high mountain environments remain preserved for future generations of climbers. This can be seen through participants’ statements such as the “ability for future generations to enjoy the same benefits of climbing high-altitude mountains” (participant from Ukraine) and “keep[ing] the mountains alive for future generations” (participant from India). Interestingly, participants living in nations near the Himalaya and Korakoram ranges described sustainability as a more intimate concept: referring to “respect” (participant living in Nepal) and “mother earth” (participant living in India). The results revealed differences in attitudes towards sustainability between cultures. Western approaches focused on the practical applications of environmental sustainability, whereas people of Eastern nationalities who participated in the study perceived sustainability as an aspect of wider values, rather than a value in itself. Whilst respondents differed in their interpretations, there was a shared belief that the mountains should be affected as little as possible by the mountaineers who use and enjoy them. The next sections detail the reality of how and why this ideal is not achieved at high altitudes.

4.2. Objective 2: Explore Sustainability Issues Associated with High-Altitude Mountaineering on 8000m Mountains

Many of the sustainability issues cited by participants in both the survey and interview, were contraventions of ‘leave no trace’ principles. Participants cited a wide variety of sustainability issues in 8000m mountaineering. Key issues were refuse, human waste, risks from climate change, short time, carbon footprint, money’s effect on sustainability, the treatment of high-altitude workers, and physical and emotional human factors. The following section will be structured according to these issues.

Refuse

One of the key issues cited by almost all participants was “trash” left on the mountain. Refuse has been highlighted as an issue by the international media and indeed the code “trash” was mentioned 29 times in the data. Examples of types of refuse cited in the survey include oxygen canisters, tents, plastic and faeces. Oxygen canisters provided an interesting case as it appears to be an issue resolving itself. Historically, oxygen canisters littered the mountains, but now they are “actually quite valuable” (Swiss participant) and so there is rising incentive to recover them. Other results from the data were less optimistic. Old tents for example were frequently cited as a challenging issue as over time they become “ingrained in the snow and ice” (Swiss participant). There was widespread concern that gear, and tents are often completely concealed and extremely heavy due to snow and ice covering. This makes them difficult and dangerous to recover. Two participants also expressed concern about the prevalence of “burning trash” in Nepal.

Human Waste

Most participants were highly concerned about insufficient human waste management on the 8000m peaks. A German and a Swiss participant both emphasised the importance of preventing accumulation of faeces in basin areas where “it will stay there forever” without any decomposition due to the extremely low temperatures. Many participants viewed the human waste situation on 8000m peaks as an environmental and public health hazard. A French participant strongly advised that human waste management and recovery should be prioritised to prevent contamination of drinking water sources. Several participants also felt that human excrement was a threat to the ecosystems of the surrounding areas, such as the valleys below these high mountain areas. Only one participant thought human waste was not a major problem, except “very, very locally” (Dutch participant).

Risks from Climate Change

Participants perceived climate change as a threat to the future security of high-altitude mountaineering. Participants widely agreed that ice coverage of the mountains was decreasing, creating “increased objective risks” (South African participant) and “more dangerous [climbing] because of the rockfall and the permafrost” (Swiss participant). Melting seracs (a pinnacle of ice formed by intersecting glacial crevasses) were also frequently cited as a cause for concern. Seracs can collapse without warning and pose high risks to climbers (Zoladek, 2014). A Swiss participant mentioned several high-altitude areas in Nepal where climate change has already changed the nature of mountaineering. The participant said Mera, Lobuche and Island Peak, which have traditionally been used as ‘beginner’ peaks, used to test mountaineers’ response to high altitude, have become more technical and higher risk climbs. As a result, these are no longer ‘beginner peaks’ (Swiss participant). There was widespread concern about the increasing dangers and high avalanche risks which are amplifying already significant risks to climbers. As it is not possible to mitigate these risks mountaineers are likely to face higher mortality rates on the 8000m mountains in the future. Conversely, a French participant explored the idea that decreased ice coverage could create more accessible and less technical high mountain environments. This participant also cited the possibility that climate change could further increase the number of climbers on the 8000m mountains. However, the same participant did also predict “increased risk of rockfalls”.

Short Time

The short length of time mountaineers designate for modern expeditions was recognised by research participants as a significant and increasing threat to sustainability. A Swiss participant provided the example of an American climber who travelled from California, summited Everest, and returned to California within two weeks. Streamlining expeditions is aided by reliance on air travel such as international flights and domestic flights as well as the relatively new development of using helicopters to get to base camps. Moreover, people are also now using “oxygen chambers to sleep in high-altitude” (British participant), allowing them to fly directly to base camp pre-acclimatised. Participants noted these strategies are now commonplace with one participant asserting that 95% of mountaineers on Manaslu are flown directly to base camp, despite the acclimatisation value of trekking. A German participant thought short holiday times are often the cause, particularly citing the USA where vacation allowance can be as little as two weeks. One participant was also wary of the dissociation between climber and environment that occurs with pre-acclimatisation and minimal time on the mountain stating “I’d hate to be only a few days on expedition”. The impact of commercialisation was also frequently mentioned in regard to expedition length. In the early years of 8000m mountaineering, the only climbers were professional mountaineers, whereas now most climbers are hobbyists, paying commercial guiding companies to lead them.

Money/Commercialisation

Participants believed the vast amounts of money associated with high-altitude mountaineering expeditions was having a negative impact on sustainability. One participant felt that recent major commercialisation has led to “a whole new sport. It’s not climbing anymore” (Swiss participant). Some participants thought that there was environmental and economic sustainability conflict, especially in Nepal, an LDC (UN, 2021). Most participants agreed “[sustainability] has gotten worse as the money has gotten bigger” (USA participant), but one offered a contrasting view citing “probably a little positive change” (Czech participant). Luxury on the mountains was seen as a key example of this with mentions of “lavish base camp setups” (British participant), with one expedition even bringing a “pool table to base camp” (Dutch participant). Participants emphasised the unnecessary nature of excessive commercialisation and cited it as an easily avoidable sustainability issue. As well, participants thought the heavy reliance on air travel was another example of money adversely impacting environmental sustainability.

Treatment of High-Altitude Workers

The results indicated that the treatment of High-Altitude Porters and Sherpas frequently presented social sustainability issues. A German participant expressed concern that Sherpas and High-Altitude Porters are driven to high-risk behaviour on the mountains due to pressures from their employers, again often related to short amounts of time for expeditions. This participant cited the death of 16 High-Altitude Porters in the 2014 Khumbu Icefall tragedy as a poignant example. He asserted that they were in the Icefall too late in the day, when the sun amplifies the risk of avalanches, which had fatal consequences. Several participants were also troubled by the undervaluing of High-Altitude Porters in what is an extremely high-risk job. Participants conveyed that there is a widespread sentiment that a Western, or perhaps any paying client’s life, is worth more than that of a Sherpa or Porter (Dutch, Belgian and Indian participants).

Physical and Emotional Human Factors

The poor treatment of workers could also relate to illness and exhaustion of mountaineers. A remarkable series of codes that arose from the data were physical and emotional human factors, such as fitness, sickness and tiredness. These intrinsic factors resulted in egocentric behaviour as a result of human self-preservation instincts. This individualistic behaviour was widely accepted to be detrimental to sustainability. Several participants even admitted that they themselves had personally been guilty of sacrificing sustainability, and contravening ‘leave no trace’ principles. One participant admitted leaving behind oxygen canisters and then deceiving officials in order to bypass the refuse management regulations in place. It was clear from the data that the physical and mental challenges of high-altitude mountaineering resulted in behaviours that defied personal values of sustainability. The link between risk, death and sustainability is further described in the next section.

4.3. Objective 3: Investigate the Potential Relationship between Risk to Human Life and Capacity to Act Sustainably on the Mountains

Death and sustainability were intertwined in the unfortunate event of climbers dying on the mountains. Many participants felt very strongly that bodies should be left on the mountain until they eventually “wash down the glacier” (German participant). A French participant believed that “[body] recovery operations generate more damage” and so bodies should be left on the mountain to avoid causing further sustainability issues. Most of the mountaineers strongly believed that lives should not be risked for a dead body. However, many participants noted that there are important factors to be considered, such as closure for families, and religious factors, as most Sherpas belong to the Nyingmapa sect of Tibetan Buddhism who believe death is of major religious significance (Spoon, 2014). This sect believe a cremation ceremony is crucial for the peace of a soul (The Associated Press, 2016). Participants observed strong correlation between the high risk of death, and lack of capacity to act sustainably.

Participants agreed that “you’ve got one main concern, and that’s getting off the mountain” (British participant). A Swiss participant expressed their commitment to sustainability in everyday life but conceded that on the mountain “you just couldn’t care less what you leave up there”. Some of the main factors causing environmentally detrimental behaviour were sickness, tiredness, AMS (acute mountain sickness), lack of experience and lack of fitness. These individual challenges resulted in focus solely on “personal sustainability” (Swiss participant). High altitude mountaineers’ frequent inability to be “concerned about the bigger picture” (British participant) results in threats to social sustainability via danger to those around them and increased strain on high-altitude porters and Sherpas. Refuse, discarded oxygen canisters and equipment also posed challenges to environmental sustainability. In almost all cases, participants agreed that this was an involuntary result of high altitude on sustainable behaviour. Participants frequently mentioned further qualification criteria for all 8000m mountains to prevent underqualified and underprepared climbers from exacerbating an already tenuous sustainability situation to begin to address this issue. The next section details other solutions raised by climbers.

4.4. Objective 4: Explore Existing and Potential Solutions to the Complex Sustainability Issues Presented by Death Zone Mountaineering

While sustainability issues in high-altitude mountaineering are complex with no simple solutions, participants explored some insightful measures. Before detailing these measures, it must be noted that many participants strongly asserted that the “best solution would be to refrain” (Dutch participant). A Swiss participant noted that we probably shouldn’t be in the hypoxic, hostile, unsustainable environments of 8000m mountains, but conceded people will likely continue mountaineering there for as long as possible. A potential compromise mentioned by participants was to reduce the numbers of climbers on the mountains by setting upper limits on the number of climbers per season or providing quotas for expedition companies.

Better Enforcement of ‘Leave No Trace’ Principles

Participants from the USA, Ukraine, Belgium and the UK recognised the successful enforcement of ‘leave no trace’ on Mount Denali in Alaska and Vinson in Antarctica. Participants stated that these successful measures included stringent monitoring of human waste, equipment and refuse. By contrast, many participants viewed the measures on 8000m mountains as insufficient and ineffective. In response to the issue, some participants suggested that expedition companies should have greater responsibility for upholding ‘leave no trace’ principles. Several participants from the UK, USA and Switzerland felt that expedition leaders and organisations should be legally responsible for ensuring ‘leave no trace’ principles are upheld to the highest degree, at least at base camps.

Human Waste Collections

It was widely accepted by participants that accumulation of human waste presents a sustainability and public health issue. Many participants also recognised that this was highly preventable, citing regulations in Aconcagua, Argentina as a valuable solution. In Aconcagua, climbers are required to collect human waste and present it to officials, who compare the actual weight, to their estimations based on the person, and the time spent on the mountain. A Swiss participant thought that personal waste collection devices were a particularly valuable solution and said they had personally used the system and that it was “really great to have”. This participant also recognised that these collection devices, often called ‘wag bags’ are not widely used in situations where it is not mandated. The measures enforced on Aconcagua were mentioned by several participants and were widely viewed as successful. The Aconcagua regulations could therefore offer a valuable model for the 8000m peaks in the Himalaya and Korakoram ranges.

Clean-Up Operations

Almost all participants thought clean-up operations were beneficial and successful, providing that risks were minimised beforehand, such as waiting for an optimal weather window. Many of these participants believed these operations should be dedicated solely to refuse collection, and not conducted in conjunction with guiding and leading clients. Many participants noted that it was significantly easier to recover refuse than a dead body, posing reduced risks to members of the clean-up operations. Several survey respondents said that they would like to see more clean-up operations in the future. A French participant did additionally note that a change in consumption behaviour is also needed as there is “a lot of non-recycled trash” on routes on and around the 8000m mountains.

Local Investment

Survey participants from the UK and South Africa suggested that investment and input into local areas was an opportunity to improve the social and economic sustainability of the areas surrounding the 8000m mountains. There were several mentions of the economic benefits of 8000m mountaineering upon local areas, mainly through employment opportunities. A Belgian participant was however concerned about the major responsibility and risk placed on Sherpas and high-altitude porters and felt that they should be paid more. A South African participant mentioned several local initiatives aimed at improving social sustainability, namely the Juniper Fund (2022), which supports mountain workers and their families, primarily in the event of injury or death. The Khumbu Climbing Centre helps to upskill Nepali climbers and promote their safety as mountain workers was another example mentioned. The Centre was founded by the family of American climber Alex Lowe after his death on Shishapangma (Alex Lowe Charitable Foundation, 2021). A South African participant also mentioned an environmental sustainability initiative, the Namche Bazaar solid-waste workshop which looks for innovative ways to deal with the waste of 60,000 trekkers and climbers, as well as their support staff (Nepali Times, 2019). The South African participant’s recognition of successful projects in the Everest region demonstrates the critical role of location specific, innovative research and development in improving the three pillars of sustainability.

5. Discussion

The discussion will be structured according to research objectives and relate the findings to the wider literature. As little research has been done on this topic, ideas for further research have been noted for each research objective.

5.1. Objective 1: Examine What Sustainability Means to CLIMBERS in the high-Altitude Mountaineering Context

It was clear that participants frequently adopted an environmental sustainability perspective, strongly correlating sustainability with ‘leave no trace’ principles. Bateman’s (2019) study investigating the sustainability challenges of mountaineering also identified ‘leave no trace’ as a significant theme. Participants from the Global West repeatedly defined sustainability as the practical application of ‘leave no trace’, whereas participants from further East tended to focus on sustainability as an aspect of wider values, adopting a more holistic approach. The results indicated a relationship between culture and sustainability values, which can be illustrated by the following interpretations:

Indian participant: “Keeping mother earth clean”.

Dutch participant: “I try to reduce my footprint as much as possible and to disturb the environment as little as possible”.

These differing views between the Global East and Global West have deep roots in history. Until relatively recently there was widespread sentiment in the West that humans were “quite separate and different from the natural world” (Nakamura, 1992, p127). As such the natural environment has often been perceived as merely a resource available for use. In mountaineering, this often translates to the idea of conquering a mountain, rather than being allowed passage, which is a belief upheld by Sherpa communities, who view the mountains as their Gods (Nepal, Mu and Lai, 2020). Nakamura (1992) argues that in the Global East, especially in India, nature has long represented natural beauty and been treasured as more than just a supply of resources. These cultural differences have resulted in a spectrum of views on sustainability, both in everyday life and high-altitude mountaineering. Lindsey (2008) suggests that sustainability can be categorised into four areas: individual, community, organisational and institutional. The contrast between individual and community are reflected in the cultural differences of participants of this research. The variation in views between people from different cultures is also likely to be influenced by the individualistic societies of the Global West and impacted by the higher prevalence of collectivism in the Global East. In order to promote positive growth of all three pillars of sustainability, it could be useful to promote the values of nature prevalent in the Global East to foster a more holistic understanding of sustainability.

5.2. Objective 2: Explore Sustainability Issues Associated with High-Altitude Mountaineering on 8000m Mountains

The results revealed that the core sustainability issues on 8000m mountains were similar to those cited by Bateman (2019) and Taylor and Komissarov (2019). These included refuse, human waste and the substantial carbon footprint of expeditions. Refuse is a widely recognised issue on the 8000m mountains, exacerbated due to the scale of waste produced during an 8000m expedition which can often last months. Participants in this study did not distinguish between refuse conditions on different mountains, or different camps within those mountains. This could have provided an interesting insight into a considerable research gap. Taylor and Komissarov (2019) investigated the refuse situation at each camp on Lenin Peak, including Base Camp, Advanced Base Camp, Camp 1, Camp 2 and Camp 3. Taylor and Komissarov (2019) found that the refuse accumulation was far worse in Camp 1 and above, largely due to the temporary nature of these camps, despite the fact that fewer climbers reach the higher camps. Taylor and Komissarov’s intimate study of Lenin Peak presented extensive data that had valuable practical applications. While this context-specific detail could not be undertaken in this study, their study provides a valuable foundation for subsequent studies by explaining the perspectives and experiences of high-altitude mountaineers in a variety of contexts.

Refuse

Participants mentioned that oxygen canisters had historically been a major problem, with bottles littering the higher camps. In recent years however, people have recognised the value (and reusability) of oxygen bottles, which ranges from €350 to €400 (Swiss participant). In addition, waste monitoring by local authorities has strengthened this, and as a result oxygen canisters no longer present a substantial waste issue on the 8000m mountains. The case of oxygen canisters presents a promising case, as their value has been harnessed to the advantage of sustainability. It would be interesting to try and apply the idea of harnessing value to other issues on 8000m peaks. For example reuse and resale of unclaimed and discarded equipment collected from the mountains.

Short Time

Unfortunately, mountaineers expect to successfully summit in a short period of time, which would not be possible without a heavy reliance on air travel. It is possible that this dissociation is a barrier to promoting a more intimate, collective approach to sustainability. Spending longer on expeditions, and incorporating more trekking and less air travel, could help foster a holistic approach to high-altitude mountaineering. Trekking would also improve fitness and acclimatisation leading to improved physical and mental wellbeing of the mountaineers, thus improving their capacity for sustainable behaviour. Having a longer expedition duration could also mean that mountaineers are less likely to attempt to summit with an insufficient weather window. This would reduce some of the safety risks and could again improve capacity for sustainable behaviour. This issue was briefly cited by Taylor and Komissarov (2019), who noted that allowing sufficient time for an expedition improves both safety and sustainability. Due to the popularity of shorter expeditions especially with hobbyist mountaineers, it is unlikely that there will be any changes without regulatory enforcement.

Climate Change

Participants were clearly concerned about the sustainability of the sport for future generations due to increasing dangers caused by climate change. This view is reinforced by the wider literature (Palomo, 2017; Kellerer-pirklbauer et al., 2012; Hock et al., 2019; Bürki, Elsasser and Abegg, 2003). Most participants thought that the 8000m peaks would become increasingly technical, rocky and avalanche prone and that 8000m mountains have already begun undergoing these profound changes. In this context, strong sustainability delimited as the non-substitutability of natural capital and acknowledging the complexity of ecosystems holds (Pellenc, Ballet and Dedeurwaerdere, 2015). Whilst briefly covered in this study, clearly more research on climate change in this context is required to bridge this research gap.

Treatment of High-Altitude Workers

The results indicated significant social sustainability issues within 8000m mountaineering that impact Sherpa communities in particular. Participants were concerned about the low social status of Sherpas and high-altitude porters within expeditions. Participants raised specific safety concerns about Sherpas and Porters being under pressure to take unnecessary risks, such as being encouraged to manoeuvre through the Khumbu Icefall during the dangerous, warmer daylight hours. The lower social status of Sherpa and porter communities has ramifications both on and off the mountains. On the mountains, Sherpas and porters face a high risk of death. One third of Everest deaths are from the Sherpa communities (NPR, 2018). Off the mountain, there is a lack of participatory engagement of the Sherpa and porter communities in discussion and implementation of climate change mitigation. Sherpa (2012) cites institutions’ undervaluing of Sherpa communities as a major issue in the response to climate change. Sherpa (2012) stated that measures taken without proper engagement of the local communities could be ineffective and even detrimental.

This research has covered a wide range of issues, in order to reduce a significant research gap. However, Taylor and Komissarov’s (2019) study illustrated that detailed analysis of issues on a case-by-case basis is necessary to develop practical solutions. If Taylor and Komissarov’s (2019) framework was applied to each 8000m mountain in individual studies, then strong context-specific recommendations could be made. Moreover, further research could help the high mountain areas around the 8000m mountains mitigate some of the growing threats to social, economic and environmental sustainability. This is particularly important since high mountain areas often have limited employment opportunities and low adaptive capacity (Maraseni, 2012).

5.3. Objective 3: Investigate the Potential Relationship between Risk to Human Life and Capacity to Act Sustainably on the Mountains

The results clearly signal a large attitude-behaviour gap. There was consensus amongst participants that a survival mind-set due to the dangers and risks of high-altitude mountaineering caused involuntary declines in sustainable behaviour. In order to reduce this unsustainable behaviour, it is clear that risk management and reduction are critical to preventing rapid degradation. This is however complex with no simple solutions. More research is undoubtedly needed to address this issue, and promote sustainable behaviour even in the hostile, hypoxic environments of 8000m peaks.

On the basis of the results of this study, some suggestions of further research can be made. In-person research could be conducted from the base camps of the 8000m mountains. This would allow an intimate relationship between the researchers and participants, which could be more effective in generating a deeper understanding of the issues. A study of this nature would pose some risk to the researchers as the base camps of 8000m mountains are subject to extreme weather conditions and hazards. As a result, any research of this nature would have ethical implications.

5.4. Objective 4: Explore Existing and Potential Solutions to the Complex Sustainability Issues Presented by Death Zone Mountaineering

The results of this research revealed several valuable solutions to sustainability issues in 8000m mountaineering. These include carbon offsetting, portable waste management solutions, and clean-up operations. These solutions offer an opportunity to improve sustainability in other extreme sports, not just on the 8000m mountains but in other dangerous and remote environments, such as the polar regions. Whilst not directly mentioned by respondents as a potential solution, as previously mentioned, this research found that allowing for more time for the acclimatisation component of the expedition, as well as possible fitness benefits would address several sustainability issues including the reduction of carbon footprints.

Enforce Leave No Trace

Refuse is one of the most widely discussed issues, perhaps as it has received media attention beyond the mountaineering community (ABC News, 2019; Forbes, 2019; New York Time, 2019). The Nepalese government has started to introduce regulation regarding this issue. This began in 2014 with a $4,000 deposit for Everest climbers, forfeited if climbers did not return with eighteen pounds of refuse. This was an important step for waste management in the region but was widely criticised by mountaineers due to the difficulty in reclaiming the deposit (Arnette, 2014). The waste deposit system was supposed to reflect the average amount of refuse per climber, but in practice monitoring and administration proved challenging and complex (Upadhyay, 2019). Waste management strategies on the 8000m mountains are changing every year, but it is clear that further development is required. Tibet, Nepal and Pakistan have taken different approaches to waste management, but all have become increasingly strict in recent years.

K2, Gasherbrum I and II, Broad Peak and Nanga Parbat (Pakistan): $68 environmental fee paid to the Central Korakoram National Park (Karim, 2020). This has been increased on K2 to $200 based on large amounts of waste present (Benavides, 2022).

Everest and Lhotse (Nepal): Each expedition member must pay a deposit of $4,000 and return with 8kg of waste, an inventory of all items required above base camp must be supplied, retrieval of bodies is the responsibility of the respective expedition company and a ‘garbage clearance letter’ will not be supplied if any bodies are not recovered and waste returned. Climbers are also required to carry a human waste management bag above base camp (Sherpa, 2024).

Manaslu, Kanchenjunga, Makalu, Cho Oyu, Annapurna I (Nepal): A deposit of $3,000 is required, which will be returned if waste is brought back (Nepal Tourism Department, 2024).

Everest (Tibet): $1,500 refuse collection fee, and a $5,000 deposit for each team forfeited if each member does not return with 8kg of refuse (Nestler, 2018).

Cho Oyu and Shishapangma (Tibet): $1,000 refuse collection fee, and a $5,000 deposit for each team forfeited if each member does not return with 8kg of refuse (Nestler, 2018)

Whilst any attempt to combat the refuse situation on the 8000m mountains denotes progress, more research should be done to determine best practice. Again, individual studies on each of the mountains in question would likely be the most beneficial in developing effective practical solutions. The regulation of this legislation is likely to be complex, but could also offer important sustainable employment opportunities.

Human Waste

While efforts have been made to target the refuse issue on 8000m peaks, human waste has been largely ignored. Outside Magazine (2015) note that only in recent years has Everest had an effective waste management system at Base Camp, and there remains no system at the higher camps. Bateman (2019) noted mountaineers produce human waste on surface snow thereby contaminating a water source. Fortunately, the results demonstrated that there are existing measures that could help improve the situation. Several participants mentioned ‘wag bags’ or ‘PETT’ (Portable Environmental Toilet) being used widely in other mountaineering contexts. These practices are often only implemented when mandated by regulation, so many participants felt that portable toilet systems should be required by regulation.

Clean-Up Operations

The research participants, and wider literature (SPCC, 2020; Nepali Times, 2021; National Geographic, 2020) both provide strong support for clean-up operations on 8000m mountains. Extreme Everest 2010 was the first clean-up expedition on an 8000m peak (The Guardian, 2010). Whilst providing obvious benefits, these expeditions pose extreme risk to those involved. In spite of this, clean-up operations have become increasingly popular, especially after the issue of refuse became headline news in 2019 (ABC News, 2019). There are now numerous non-profit organisations whose sole purpose is to promote improved waste management on the 8000m peaks, largely focused on Everest and the wider Khumbu region. Clean-up operations should not be a substitute for sustainable behaviour. Undoubtedly, more must be done to create improved infrastructure for waste management, to cope with the strains of rapidly growing mountaineering tourism.

Local Investment

There have been numerous instances of mountaineers ‘giving back’ to local communities through development projects. This investment in social and economic sustainability is helping to offset the negative environmental impacts imposed on the areas around the 8000m mountains. Høyem (2020) notes that people tend to engage with sustainability on a more local level, and it is therefore understandable that mountaineers forge an intimate connection with areas around the 8000m mountains. The root of this mountaineering philanthropy can be traced back to Edmund Hillary’s establishment of the Himalayan Trust and Tenzing Norgay’s foundation of the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute (National Geographic, 2012). Since then, there have been numerous non-profit organisations set up by climbers and their families in the wider Himalaya and Korakoram area. These projects are frequently effective as they are run by people who have an intimate knowledge and relationship to these areas. For example, Conrad Anker and Jennifer Lowe established the Khumbu Ice Climbing Centre as part of the Alex Lowe Foundation, in order to upskill mountain workers and increase their safety, as well as employing local climbing guides as teachers during the quiet winter season. This initiative improves sustainability economically, socially and environmentally. Improving the safety of mountain workers is likely to improve capacity to act sustainably. Incorporating sustainability awareness into these training programmes could help to create sustainability ambassadors. Another pertinent example of a successful project is the UIAA’s (2021) ongoing Everest Recycling Challenge, which generates sustainable jobs through the creation of innovative waste management solutions for the Himalayas. The allure of the Himalaya and to a lesser extent the Korakoram, mean that they attract substantial investment, which should be increasingly harnessed to foster sustainability growth. There is a research gap pertaining to the perspectives of local communities regarding high-altitude mountaineering. This would be an interesting insight to explore, but was outside the scope of this study and again this type of research should be specific to local contexts.

The Paradox of Sustainable Development

As previously mentioned, trade-offs between environmental sustainability and economic or social development happen frequently (Sandker, Ruiz-Perez, and Campbell, 2012; McShane et al., 2011; Hirsch, Brosius, and Gagnon, 2013). The 8000m mountains are no exception. If discussion and implementation engages the local community, high-altitude mountaineering offers a major economic stimulus to the regions, providing employment and investment in infrastructure, and thereby helping to develop social sustainability. This study has however shown that there are numerous environmental challenges presented by this sport, some unique due to the high risks and hostile environment, and some shared with outdoor sports and nature related tourism. Participants conceded that the only way to achieve true environmental sustainability on the 8000m mountains was to cease mountaineering completely. Thus, 8000m mountaineering provides an example of the three paradoxes of sustainable development, outdoor sport and sustainable tourism.

This paper investigated sustainability on all 8000m mountains. Everest has always attracted the most mountaineers, compared to the other 8000m mountains, which has resulted in a greater wealth of literature and information. This has resulted in a greater focus on Everest in this paper than the other mountains studied. This focus is perhaps reflective of the greater need for understanding of the sustainability issues and development of effective management.

6. Conclusions

This study has investigated how climbers perceive sustainability in the high-altitude mountaineering context, the potential relationship between risk to life and capacity to act sustainably, and sought solutions to these complex issues. All areas of research that have received scant attention. This research shows that the severe risks and challenges of 8000m mountaineering reduce mental capacity for sustainable behaviour. As a result, even the most conscientious climbers can demonstrate unsustainable behaviour.

The results of this study show that there are serious sustainability issues in 8000m mountaineering. The results demonstrate that climbers understand the profound implications that climate change is already beginning to have on the 8000m mountains. These changes are increasing the dangers associated with a sport that already takes place in a hypoxic, hostile environment, and is likely to make the sport even more unsustainable. In order to prevent further degradation of these delicate, high-altitude environments more must be done to improve sustainability.

Based on this study, some recommendations can be made. Mountaineers must have sufficient fitness and preparedness for expeditions, as well as allowing sufficient time to acclimatise. The shortened time of expeditions causes behaviours that exacerbate several sustainability issues including: increased likelihood of risky behaviour and pressure on workers to take risks ultimately leading to more injury, deaths, and bodies on the mountains, hasty behaviours that generate more waste, and increased air travel causing higher carbon emissions. Mountaineering needs to be a fast activity once on the mountain, but promoting slow acclimatisation would address the root cause of many sustainability problems.

Along those lines, it may also be beneficial to promote the more holistic values prevalent in the Global East, such as respect for nature and an understanding of the fragility and interconnectedness of ecosystems. Nonetheless, practical solutions to specific issues such as making personal human waste management compulsory, further enforcement of recovery and removal of refuse and equipment, and legislating for the reduction of expedition air travel should also be encouraged. Moreover, the purchase of equipment locally could benefit local communities economically and reduce carbon emissions in air shipment of freight. Further research would potentially allow a model of best practice for sustainability to be developed to be disseminated to foster positive change.

There is hope for the Himalaya and Korakoram ranges. Climbers are engaging with the discipline of sustainability within their sport. There are numerous examples of mountaineers engaging in projects to develop sustainability in the region, through non-profit organisations. There are growing attempts to create innovative waste management solutions and this and other challenging issues are now eliciting dialogue across the globe. In conclusion, despite the poor current state of sustainability on the 8000m peaks, there is cause for optimism. By drawing upon successful measures applied in similar contexts, and more focused further research, it is likely that sustainability on the 8000m peaks could be significantly improved.

Author Contributions

Mairead Morony undertook this research to fulfil the requirement of a dissertation for her undergraduate studies at the University of Leeds under the supervision of Dr Natalie Kopytko. Mairead Morony is responsible for conceptualization as the idea of gathering sustainability perspectives of mountaineers specifically in the high mountain environment belongs to her alone. Mairead Morony developed the methodology under the guidance of Dr Natalie Kopytko. Mairead Morony conducted formal analysis and data curation independently. The dissertation was written solely by Mairead Morony with feedback provided by Dr Natalie Kopytko. The current manuscript has been edited and reviewed by Dr Natalie Kopytko. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Leeds.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A: Pilot Questionnaire

Appendix B: Main Questionnaire

Appendix C: Interview Protocol

Hello, thank you for speaking to me today, I hope you’re well.

This is an interview following up on your survey responses and is seeking to gain a deeper understanding of sustainability issues in 8000m mountaineering.

Your interview responses will be treated according to the same participant information displayed in the survey. If you wish to withdraw at any time, please just email me. Or if you have any questions please feel free to drop me an email. Before we begin, do I have your permission to record this interview?

Do you have any questions before we begin?

What do you think are the three most significant factors affecting a mountaineer’s footprint on an 8000m peak? And what do you think can be done to mitigate this?

How do you think the heightened risk of death in 8000m mountaineering affects a climber’s capacity to act sustainably?

Clean-up operations and body recoveries are high risk operations, do you think the benefits outweigh the risks?

What are your thoughts on insurance companies funding clean-up operations if a climber does not make it off the mountain?

Do you think existing sustainability measures on the 8000m mountains go far enough? If not, what additional measures do you think would be particularly beneficial?

Climate change is causing glacial retreat and permafrost degradation, what impact do you think this will have on mountaineering on the 8000m mountains.

Do you have anything else to say on the topic?

Thank you for your time.

Appendix D: Table of Codes from the Data

Table A1.

Codes derived from the data.

Table A1.

Codes derived from the data.

| Codes |

|---|

| Avalanches |

Role of Expedition companies |

Luxury on the mountains |

Existing Sustainability Measures |

| Behaviour change |

Expedition Clean-Ups |

Generators |

Faeces |

| Bodies on the mountain |

Cheap Outfitters |

Medical practices |

Water |

| Burning trash |

Short Expedition Time |

Money vs sustainability |

Families and closure |

| Challenges of Policing Sustainability |

Sickness |

More Rescue Operations |

Fitness |

| Clean-up operations |

Solutions |

Offsetting |

Footprint |

| Climate change |

Sustainability |

Oxygen Cylinders |

Footprint of Flying |

| Sustainability Consciousness |

Tents |

Permafrost degradation |

Geology |

| Cost of rescue |

Tiredness |

Respect the mountains |

High Risk Behaviour of Porters and Sherpas |

| Denali Sustainability |

Sustainability Tokenism |

Risk and Death |

Increased Number of Climbers |

| Economic and social improvements |

Trash |

Logistics |

Insurance |

| Egocentricity |

Undervaluing of Sherpa |

Lack of Experience |

Lack of Skills |

| Ethics of recovery operations |

Why Climb an 8000er? |

Leave No Trace |

|

References

- ABC News, 2019, Mount Everest tackles 60,000-pound trash problem with campaign to clean up waste. [online] [accessed 5th January 2022] Available from: https://abcnews.go.com/International/mount-everest-tackles-60000-pound-trash-problem-campaign/story?id=62773297.

- Alex Lowe Charitable Foundation, 2021, The Khumbu Climbing Centre. [online] [accessed 14th February 2022] Available from: https://www.alexlowe.org/projects/kcc/.

- Anand, A.C., Sashindran, V.K. and Mohan, L., 2006. Gastrointestinal problems at high altitude. Tropical Gastroenterology, 27(4), p.147.

- Andrade, C., 2021. The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 43(1), pp.86-88. [CrossRef]

- Apollo, M. and Andreychouk, V., 2020. Mountaineering and the natural environment in developing countries: An insight to a comprehensive approach. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 77(6), p942-953. [CrossRef]

- Arnette, A., 2014, Everest 2014: Nepal Takes Control of Everest, and Climbers [online] [accessed 5th January 2022] Available from: https://www.alanarnette.com/blog/2014/03/04/everest-2014-nepal-takes-control-everest-climbers/.

- Arnette, A., 2022, How Much Does it Cost to Climb Mount Everest? [online] [accessed 15th February 2022] Available from: https://www.alanarnette.com/blog/2021/12/13/how-much-does-it-cost-to-climb-mount-everest-2022-edition/.

- Azam, M.F., Kargel, J.S., Shea, J.M., Nepal, S., Haritashya, U.K., Srivastava, S., Maussion, F., Qazi, N., Chevallier, P., Dimri, A.P. and Kulkarni, A.V., 2021. Glaciohydrology of the himalaya-karakoram. Science, 373(6557), p.eabf3668. [CrossRef]

- Barriball, K.L. and While, A., 1994. Collecting data using a semi-structured interview: a discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing-Institutional Subscription, 19(2), pp.328-335. [CrossRef]

- Basnet, K., 1993. Solid waste pollution versus sustainable development in high mountain environment: A case study of Sagarmatha National Park of Khumbu region, Nepal. Contributions to Nepalese Studies, 20(1), pp.131-139.

- Becken, Simmons and Frampton, 2003, Energy use associated with different travel choices. Tourism Management 24(3):267-277. [online] [accessed 2nd February 2022] Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/223473194_Energy_use_associated_with_different_travel_choices.

- Beniston, M., 2003. Climatic change in mountain regions: a review of possible impacts. Climate variability and change in high elevation regions: Past, present & future, pp.5-31. [CrossRef]

- Benavides, A., 2022, ExplorersWeb. K2 Garbage: Who Left It, Who Will Clean It Up and What Should Happen to Those Responsible? [online] [accessed 25th July 2024] Available from: https://explorersweb.com/k2-garbage-who-left-it-who-will-clean-it-up-and-what-should-happen-to-those-responsible/.

- Brewer, T.L., 2019. Black carbon emissions and regulatory policies in transportation. Energy Policy, 129, pp.1047-1055. [CrossRef]

- Britannica, 2021, Lenin Peak. Mountains and Volcanoes. [online] [accessed 28th February 2022] Available from: https://www.britannica.com/place/Lenin-Peak.

- Brundtland, 1987, Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, p16 [online] [Accessed 9th December 2021] http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf.

- Bürki, R., Elsasser, H. and Abegg, B., 2003, April. Climate change-impacts on the tourism industry in mountain areas. In 1st International Conference on Climate Change and Tourism (pp. 9-11).

- The Associated Press, 2016, Death on Mount Everest leads to risky effort to recover bodies. [online] [accessed 17th June 2022] Available from: https://www.denverpost.com/2016/05/28/death-on-everest-leads-to-risky-effort-to-recover-bodies/.

- Canavan, B., 2017. Narcissism normalisation: Tourism influences and sustainability implications. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(9), pp.1322-1337. [CrossRef]

- CCAC, 2016, Climate and Clean Air Coalition: Black carbon: key message. [online] [accessed 17th February 2022] Available from: http://www.ccacoalition.org/en/resources/factsheet-black-carbon-key-messages.

- Central Bureau of Statistics, 2021, Analytical Report Tourism. [online] [accessed 16th February 2022] Available from: https://cbs.gov.np/analytical-report-tourism-industry/.

- Charmaz, K. 2014, Constructing Grounded Theory. London: SAGE.

- Clark, G. and Johnston, E.L., 2017. Australia state of the environment 2016: coasts, independent report to the Australian Government Minister for Environment and Energy. Australian Government Department of the Environment and Energy, Canberra.

- Crust, L., 2020. Personality and mountaineering: A critical review and directions for future research. Personality and individual differences, 163, p.110073. [CrossRef]

- Danaeifard, H. and Emami, S.M., 2007. Strategies of qualitative research: a reflection on grounded theory. Strategic Management Thought, 1(2), pp.69-97.

- Dawadi, S., Pandey, P. and Pradhan, R., 2020. Helicopter evacuations in the Nepalese Himalayas (2016–2017). Journal of Travel Medicine, 27(2), p.taz103. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J., Johnston, M.J., Stewart, E.J., Lemieux, C.J., Lemelin, R.H., Maher, P.T. and Grimwood, B.S.R., 2011. Ethical considerations of last chance tourism. Journal of Ecotourism, 10(3), pp.250-265. [CrossRef]