1. Introduction

Coronavirus (COVID-19) has already caused tremendous health and socio-economic challenges worldwide. As there is no treatment available till now, preventing COVID-19 with a safe and effective vaccine has been given the most importance (Wang et al., 2021), which is considered the most successful public health intervention throughout the last century (Hajj Hussein et al., 2015). Even with safe and effective vaccines, the vaccination coverage program’s success relies on several other factors, such as willingness to vaccinate and for the vaccine (Harapan et al., 2020; Neumann-Böhme et al., 2020). The intention to be vaccinated and the success of vaccination coverage programs has been influenced by the economic considerations of mass people (Cerda & García, 2021; Sarker et al., 2020). In this regard, willingness to pay (WTP) emerged as a concept where it is defined as the maximum amount of money an individual is willing to pay for a vaccine, health services, or technology (Kim et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2020).

To battle against the vulnerability caused by COVID-19, the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) has launched its largest-ever vaccination program, providing vaccines free of charge. However, sustaining this free vaccination program is challenging (McQuestion et al., 2011) for a developing country with a large population like Bangladesh. On the other hand, from the demand side perspective, individual health out-of-pocket expenditure in Bangladesh is already 74%, and 24.3% of the total population living behind the poverty line. (BBS, 2019; MoHFW, 2015), leading to paying fully for vaccines, an impossible task. Assessing (WTP) can offer insights into public demand and guide GoB’s future pricing and payment strategies in this regard. (Harapan et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021).

Several studies in Bangladesh have measured WTP in the non-COVID situation (Ahmed et al., 2016; Islam et al., 2015; Sarker et al., 2020), and there is much evidence of assessing WTP in COVID-19 context in various countries (Sallam et al., 2022; Dias-Godói et al., 2021; Berghea et al., 2020; García & Cerda, 2020; Lin et al., 2020). WTP, both in COVID and non-COVID contexts, is determined by socio-economic and demographic factors (Harapan et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Mudatsir et al., 2020; Rajamoorthy et al., 2019; Sarker et al., 2020), health-related factors, knowledge about the disease and vaccine (García & Cerda, 2020), different constructs of health belief model and behavioral factors (Wong et al., 2020).

However, there is scanty evidence regarding WTP toward the COVID-19 vaccine in Bangladesh. Existing studies only showed the prevalence and median WTP toward the COVID-19 vaccine (Kabir et al., 2021) and associated factors (Banik et al., 2021) but lacked representativeness of the Bangladeshi population as the study was only online based. Thus, our study initiated a nationwide survey to assess the prevalence of WTP regarding the COVID-19 vaccine and its associated correlates. It has important public health policy implications to identify vulnerable groups and determine a strategy to create an optimum situation where government and individual health expenditures balance.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

A cross-sectional research design was adopted in this study. The calculated sample size was 1635 using (Z2pq/e2)*Deff*NR- formula. Where Z- score for 95% confidence interval was 1.96, the prevalence of willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine from an earlier study, p= 32.5% (M. Ali & Hossain, 2021). We used a margin of error, e= 0.03, for sampling variation design effect (Deff) = 1.6 and a 10% non-response rate.

As GoB intended to initiate a mass vaccination program from February 7, we fixed 1 to February 7 for data collection time. Data were collected online and through face-to-face interviews through Google Forms using Bengali. The survey form link was circulated within the networks of research team members through E-mail, Facebook, WhatsApp, and other platforms. Respondents were also requested to share the link with their networks to reach maximum people. After three days, data were checked for the divisional and age-sex-specific distribution. Then, face-to-face interviews were started to determine the population’s national representation in terms of age, sex, residence, division, and marital status using quota sampling. Data were collected from randomly selected two districts of each of the eight divisions. Four days were allocated to collect data from face-to-face interviews, and interviewers maintained proper health measures while conducting interviews.

For offline data collection, the selection criteria to participate in this study were to be at least 18 years old and know about the vaccine of COVID-19—another additional criterion for the online respondents’ reading and writing ability. During the interview, 112 respondents did not consent, and another 26 did not know about the COVID-19 vaccine. Therefore, the final sample size was 1497.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome Variables

Two questions were used to assess the respondents’ WTP. The first question was, "Would you like to pay for the COVID-19 vaccine?" with a binary response (Yes/ No). If the response to the first question was ‘yes,’ then the second question was “What is the maximum amount you are willing to pay for the COVID-19 vaccine?”.

2.2.2. Independent Variables

Several socio-economic and demographic variables, such as age, sex, religion, marital status, place of residence, household income, and occupation, were used as independent variables in this study.

Respondents’ self-health status (3 categories), self-morbidity status (10 binary questions), and infection status from COVID-19 of self, family members, and friends (3 binary questions) were used as respondents’ health-related independent variables.

Knowledge of the COVID-19 vaccine was assessed using four Likert-type items. It ranged between 1 and 20 scores, with a higher score indicating higher knowledge where the Cronbach alpha (α) was 0.643.

Six binary (yes=1, no=0) questions were used to measure knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccination process where Cronbach alpha (α) was 0.765 with good internal consistency. The higher the scores indicate a better knowledge.

Nine Likert-type items were used to assess conspiracy related to the COVID-19 vaccine (α=0.716), ranging between 9 and 45 scores, where a higher score indicates higher conspiracy toward the COVID-19 vaccine.

Preventive behavioral practices related to COVID-19 were measured using three items, ranging between 1 and 12, with a higher score indicating better preventive practices with the Cronbach alpha (α=0.857).

Attitude towards COVID-19 Vaccine: Six Likert-type items were used to assess COVID-19 vaccine-related attitudes (α=0.739), ranging between 6 and 30 scores. A higher score on this scale directs higher negative attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine.

Subjective Norm: Subjective norm toward the COVID-19 vaccine was assessed using one 5-point item: I believe my family members will support me in getting vaccinated against COVID-19.

Perceived Behavioral Control: It was measured using one 5-point item: If I want, I can register for COVID-19 vaccination.

Anticipated Regret: The regret of not getting vaccinated was assessed using one 5-point item: If I do not get a COVID-19 vaccine and end up getting Coronavirus, I will regret not getting the vaccination.

The Health Belief Model was constructed by four components: Perceived Susceptibility, Perceived Severity, Perceived Benefits, and Perceived Barriers.

Perceived Susceptibility: Perceived Susceptibility of COVID-19 was measured by two 5-point Likert scale questions where Cronbach alpha, α is 0.657.

Perceived Severity: Two 5-point Likert-type items were used to measure the perceived severity of COVID-19 where Cronbach alpha, α is 0.612.

Perceived Benefits: Three 5-point Likert scale questions were used to measure perceived benefits of the COVID-19 vaccination where Cronbach alpha, α is 0.841.

Perceived Barriers: The perceived barriers (α=0.739) of getting the COVID-19 vaccination were measured using five 5-point Likert scale questions.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

We first employed univariate descriptive statistics (Percentage, mean, standard deviation-SD) for all the variables. At the bivariate level for WTP, the Chi-square test and point Bi-serial Correlation were employed, and then statistically significant variables (P≤0.05) at the bivariate level were entered into a hierarchical logistic regression model to assess WTP determinants. We used only descriptive analysis (mean and Median) for WTP’s highest amount of money. Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 26.

2.4. Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was taken from the Bangladesh Medical Research Council-BMRC (Registration No. 39131012021). There was involuntary participation in the research, and no incentives were provided to the participants. Firstly, the aims, objectives, potential scopes, and implications of the findings of this study were communicated to the participants, and then the participants provided their consent. After that, the respondents participated in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Background Characteristics of the Participants

The mean age of the respondents was 33.67 (SD=12.94), where more than half of the respondents (53.8%) were male (

Table 1). About 86.9% of the respondents were Muslim, and nearly two-thirds (61.6%) were married. Most respondents (79.2%) had at least secondary and higher secondary education. Almost two-thirds (64.3%) of respondents were from rural areas, and the highest percentage of respondents (31.9%) were from the Dhaka division (

Table 1). One-third (31.6%) of the respondents were students and unemployed. The respondents’ mean number of household members was 4.95, and they had a mean collective family income of 37,627 BDT. About 58.7% of the respondents identified themselves as having good health status. The mean score of knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine, vaccine process, vaccine conspiracy, and behavioral practice were 11.40, 2.84, 12.65, and 8.80, respectively (

Table 1).

3.2. The Prevalence of Willingness to Pay (WTP) for the COVID-19 Vaccine

The prevalence of willingness to pay for the COVID-19 vaccine was 50.9%. However, almost half of the respondents (48.1%) refused to pay any money for the COVID-19 vaccine.

3.3. Differentials of WTP for COVID-19 Vaccine

WTP was statistically significantly (P

0.05) varied by age, religion, marital status, education, place of residence, administrative division of Bangladesh, occupation, the coronavirus infection status of self, family & friends, household size, and household income (

Table 1). Knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine and vaccination process, COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, behavioral practice, attitude toward a vaccine, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, anticipated regret, perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, and barriers were statistically significantly correlated with WTP.

3.4. Correlates of WTP for COVID-19 Vaccine

The significant variables at the bivariate level were entered into a hierarchical logistic regression model to assess correlates of WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine. We produced three models in this study. The first model was constructed with variables such as socio-economic and demographic, knowledge of COVID-19 vaccine and vaccination process, COVID-19 Vaccine Conspiracy, and preventive behavioral practices related to COVID-19. The second model was constructed with the variables of the first model and components of the theory of planned behavior. Furthermore, the final model included all second and health belief model variables (perceived susceptibility, severity, barrier, benefits, and health-related variables). The final model showed that religion, education, administrative division of Bangladesh, household income, knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine & vaccination process, behavioral practice, attitude toward a vaccine, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, anticipated regret, and barriers were statistically significant (P

0.05) predictors of WTP (

Table 2).

According to the final model, respondents of other religions were 50% more likely to pay for the COVID-19 vaccine than Muslims (P= 0.037). Similarly, education was a statistically significant (P= 0.008) predictor of WTP, where respondents who had Graduate (aOR= 2.2, P= 0.007), Masters & MPhil/PhD (aOR= 2.0, P= 0.030) degrees had higher WTP than respondents who had no education (

Table 2). Regional variation of WTP was found and division was a significant predictor of WTP (P<0.001), which showed respondents from Chattogram (aOR=2.5, P=0.001), Dhaka (aOR=2.3, P=0.001), Khulna (aOR=2.5, P=0.003), Rajshahi (aOR=2.7, P=0.001), Rangpur (aOR=2.4, P=0.005) and Sylhet (aOR= 4.1, P<0.001) had higher WTP than respondents from Barisal (

Table 2). Our results showed that WTP increased with household income (aOR=1.0, P=0.039). Findings showed that with increasing level of knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine (P=0.003), Behavioral preventive practices (P<0.001), higher subjective norm (P=0.009), higher anticipated regret (P=0.005) and increasing perceived benefit from the vaccine (P=0.029) WTP increased by 10%, 10%, 20%, and 10% respectively (

Table 2). On the other hand, a higher negative attitude toward the COVID-19 vaccine (P<0.001) and higher difficulty in registration (P=0.006) decreased WTP by 10% and 10%, respectively. (

Table 2).

3.5. Willingness to Pay the Highest Amount of Money

Mean and Median of the willingness to pay the highest amount of money among the respondents was 754.55 BDT (US$ 8.93) and 300 BDT (US$ 3.55) for COVID-19 vaccine. Nearly half of the respondents (48.1%) were unwilling to pay for vaccines. The willingness to pay the highest amount of money ranged from the lowest of 1 BDT (US$ 0.012) to the highest of 30,000 BDT (US$ 353.73).

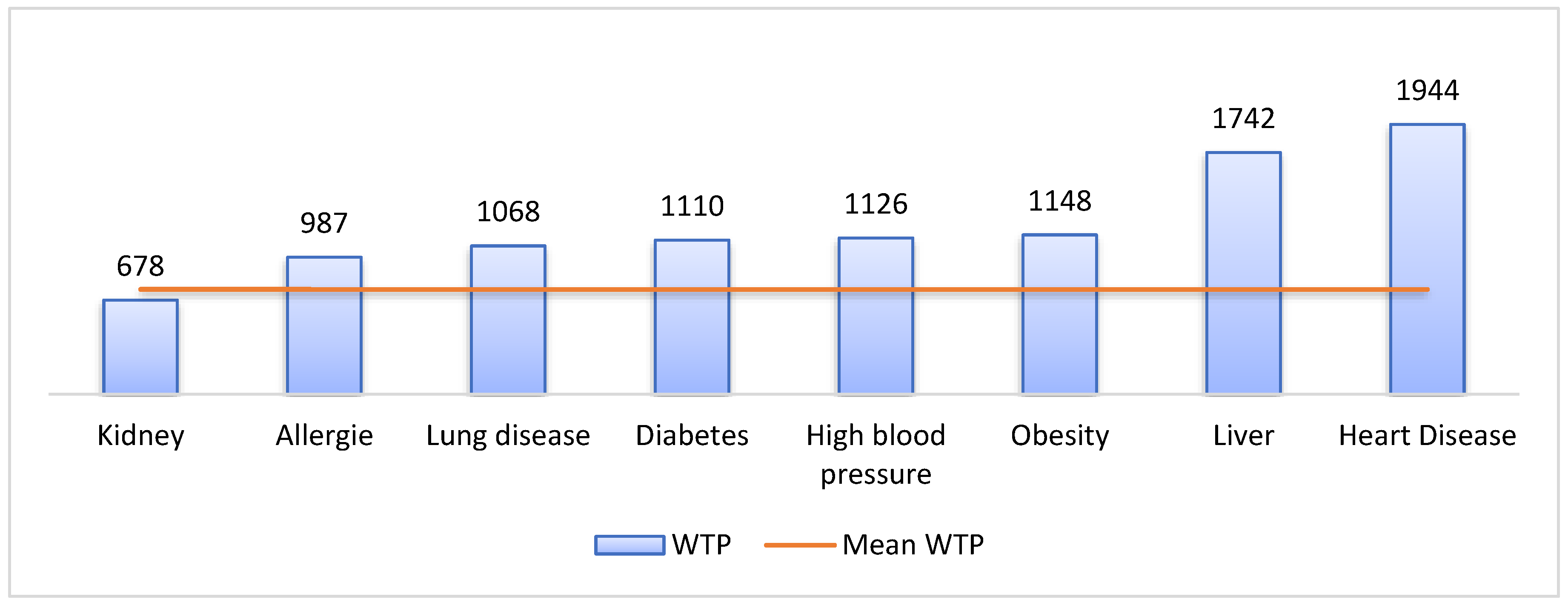

Figure 1 explains that the mean WTP varied by the specific morbid condition of the respondents, and it also explains that the mean WTP by the morbid condition of the respondents (except WTP by respondents who had kidney disease) was higher than population mean WTP (754.55 BDT). Respondents with heart disease wanted to pay an average of 1944 BDT (US

$ 22.94), whereas those with kidney disease had a mean WTP of 678 BDT (US

$ 8).

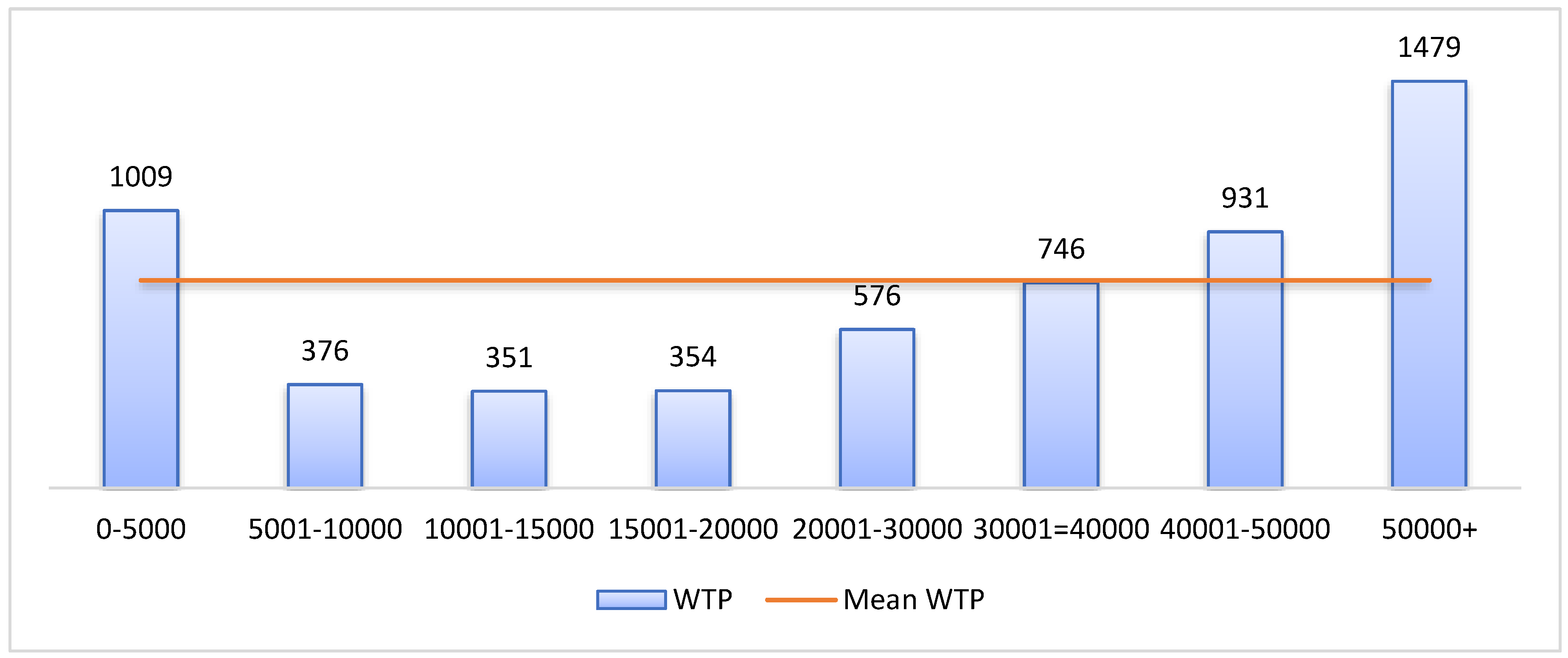

Figure 2 explains that mean WTP varied by household income. There was an increasing trend of WTP with increasing income except for the lowest income category (0-5000 BDT). Respondents from the 5001-10000 BDT income group had a mean WTP of 376 BDT (US

$ 4.44). On the other hand, the mean WTP of 50000+ BDT income group was 1479 BDT (US

$17.45).

4. Discussion

A successful vaccination program depends not only on safe and effective vaccines but also on vaccine hesitancy, willingness to pay etc. Our study objective was to explore the WTP toward the COVID-19 vaccine and its associated factors to identify the vulnerable groups and possible interventions. In this regard, Our study demonstrated that half of the respondents (50.9 %) willingly paid for the COVID-19 vaccine in Bangladesh. The mean and median WTP were 754.55 BDT (US$ 8.93) and 300 BDT (US$ 3.55). However, an existing online survey on WTP found a greater prevalence of WTP (68.4%) toward the COVID-19 vaccine than our study, and even the median WTP (U.S. $ 7.08) was also found to be higher than our findings (Kabir et al., 2021). These differences might be attributed to the variation in the study population selection of the two studies. The existing study collected data through an online platform, thus leading to selection bias of the study population, but our study collected data from online and face-to-face interviews. Several studies were also found in the world context with higher prevalence and higher mean and Median of WTP than our study (Berghea et al., 2020; Harapan et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020). As there is a concern about vaccine resistance and budgetary limitation, which creates an expectation that the government would fully subsidize the vaccine, this kind of expectation contributes to the lower willingness to accept and pay for the vaccine(Catma & Varol, 2021). However the lower prevalence of WTP is a concerning issue to attain herd immunity because there is an estimated that perhaps 60% of the population needs to be under an immunization system to ensure the effectiveness of any vaccine(Harapan et al., 2020).

Our study findings found that religion significantly predicts WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine in Bangladesh. Muslims had significantly lower WTP than other religions (Hindu, Christian, and Buddhism), and the existing literature supports the findings(Harapan et al., 2020). The Muslim community is known for its fatalistic view about health and appreciation, acceptance & patience for their current situation(Ali, 2020; Elbarazi et al., 2017). In Bangladesh, the majority of the population is Muslim. Muslims have various religion-related conspiracy beliefs, lower perception and level of knowledge regarding health and vaccines, and trust issues on the vaccines of other non-Muslim countries, which may influence their decision to purchase a vaccine and ultimately interplay for lower WTP toward COVID-19 vaccine(de Figueiredo et al., 2020; Larson et al., 2015; Sallam et al., 2021; Sulaiman, 2014).

Our study shows that education significantly predicts WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine (Mudatsir et al., 2020; Rajamoorthy et al., 2019). In our study, respondents who had Graduate and Masters & MPhil/PhD level education had higher WTP than respondents who had no education. Educated people are more likely to be conscious about health and more willing to prevent diseases through preventive care such as vaccination(Lu et al., 2017; Mora & Trapero-Bertran, 2018; Zajacova & Lawrence, 2018). Education also determines the knowledge of health & vaccines, and those with a low level of knowledge cannot grow willingness to pay for vaccines (Mora & Trapero-Bertran, 2018; Worasathit et al., 2015). Educated people are more likely to have higher incomes, giving them higher purchasing power.

In our study, household income was positively associated with WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine in Bangladesh. Income has proved to be the most influencing factor for determining WTP both in COVID and non-COVID vaccines (Sallam et al., 2022; Harapan et al., 2020; Sarker et al., 2020; Rajamoorthy et al., 2019). Those from higher income groups have the higher purchasing power to invest more in health and practice healthier behaviors such as WTP toward vaccines(Sarker et al., 2020; Zajacova & Lawrence, 2018). Similarly, wealthier families want to pay more to the health sector to avoid the fatality of diseases and are more interested in improving their immune system through vaccination(Rezaei et al., 2020). Again, higher-income individuals tend to be educated, making them conscious about health.

The study findings revealed a divisional disparity regarding willingness to pay (WTP) for the COVID-19 vaccine in Bangladesh. There is a lack of evidence of regional variation with WTP for vaccines. However, there is evidence of socio-economic and demographic contextual variation among divisions in Bangladesh (BBS, 2018). Barisal and Rangpur are the two divisions with the highest poverty headcount ratio, whereas Sylhet, Dhaka, Khulna, and Chattogram have much lower poverty headcount ratios (BBS, 2019). Comparative poor households in Barisal and Rangpur may lead to lower willingness to pay (WTP) for the COVID-19 vaccine.

Apart from the socio-economic and demographic status, the knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine and preventive behavioral practices were associated with higher WTP, and the literature supports the present study’s findings (García & Cerda, 2020; Harapan et al., 2017). Increased knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine indicates more reliable knowledge regarding vaccine’s safety and effectiveness, which increases trust in the vaccine; thus, WTP may increase. Again, people with higher preventive behavioral practices tend to be educated and health conscious, so they are expected to have higher WTP towards any vaccine (Hossain et al., 2021).

The study findings show that the Theory of Planned behavior components were statistically significant predictors of WTP. The main argument of TPB is that behavior intention is the most important determinant of health behavior, in this case, WTP (National Cancer Institute, 2005). Our study findings found that respondents with a higher negative attitude toward vaccines also had lower WTP. Attitude acts as a personal evaluation of a behavior; as a result, the intention to WTP decreases with a higher negative attitude. Similarly, perceived behavioral control indicates that performing health behavior is not solely on the respondent’s hand; in this case, it is difficult to register. In our study, difficulty in online registration acts as a structural barrier that reduces WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine. On the other hand, subjective norms and anticipated regret in our study findings positively associated with WTP for the vaccine. In our study, respondents whose family members approved their decision to take the vaccine and highly regretted getting Coronavirus disease had higher WTP, and it is also a part of subjective norms because it acts as permission from family members or friends toward a health behavior(National Cancer Institute, 2005). Thus, intention toward a health behavior regarding a disease or vaccine is driven by attitude toward the disease or vaccine, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control etc. (Ajzen, 1991; National Cancer Institute, 2005).

Our study found Perceived benefits from vaccines as a significant predictor of WTP. When people perceive that the disease will be responsible for high vulnerability regarding their health and economic condition and getting a vaccine can eliminate that cost (the cost of the disease, both health and economic, is higher), they are more willing to pay (WTP) for the vaccine and helps to increase WTP (National Cancer Institute, 2005).

Similarly, our findings revealed that those who are experiencing severe morbid conditions, are more likely to pay a high amount of money for the COVID-19 vaccine. The severity of the disease is associated with a higher intention to pay because those who are already going through the morbid situation are not confident about their immune system to protect from disease and are more likely to pay for an effective vaccine (Hou et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2014).

This study intends to explore the prevalence and associated factors of WTP for a COVID-19 vaccine in Bangladesh, which will help GoB and policymakers promote a successful vaccination program at a larger scale among the mass population by eliminating economic challenges. However some limitations should be taken for granted before accepting our findings. Our study adopted a cross-sectional study design, which is limited to properly generating causal inference due to temporal issues. Again, we used non-probability sampling to reach our study population. We collected self-reported data on health status and other socio-demographic variables, which may suffer from recall bias. Finally, our study is almost nationally representative in terms of age, sex, religion, residence, and marital status in the context of Bangladesh, but could not represent in terms of education, occupation, or income status.

5. Conclusion

The study findings propose that health promotion materials and awareness campaigns as a part of the Behavior Change Communication (BCC) program should be developed to increase the knowledge level about the COVID-19 vaccine. It will also increase preventive behavioral practices and reduce negative attitudes towards vaccines and vaccine-related conspiracy beliefs. Here, mass media can be an effective platform to circulate the accurate message of the COVID-19 vaccine, and religious leaders can also be incorporated to mitigate religion-related mistrust and misconception. Policymakers should rethink the online registration procedure for vaccine uptake because it stands as a structural barrier to WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine. Regarding our findings an alternative easy system should be introduced with the mass-population to achieve sustainability of the vaccination program. Authors suggest that policymakers should think of a subsidization program considering socio-economic stratification and where lower-income groups should be highlighted to reduce the catastrophic income challenge regarding WTP for the COVID-19 vaccine. Otherwise, a reasonable price regarding our findings should be fixed for the COVID-19 vaccine to be affordable for all, which helps achieve the the highest vaccine coverage and run a successful vaccination program without economic hardship.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Mohammad Bellal Hossain, Md. Zakiul Alam, Md. Syful Islam, Shafayat Sultan, Md. Mahir Faysal, Sharmin Rima, Md. Anwer Hossain, Abdullah Al Mamun. Data curation: Mohammad Bellal Hossain, Md. Zakiul Alam, Shafayat Sultan, Md. Mahir Faysal, Sharmin Rima, Md. Anwer Hossain, Abdullah Al Mamun. Formal analysis: Mohammad Bellal Hossain, Md. Zakiul Alam, Shafayat Sultan. Investigation: Mohammad Bellal Hossain, Md. Zakiul Alam, Md. Syful Islam, Shafayat Sultan, Md. Mahir Faysal, Sharmin Rima, Md. Anwer Hossain, Abdullah Al Mamun. Methodology: Mohammad Bellal Hossain, Md. Zakiul Alam, Md. Syful Islam, Shafayat Sultan, Md. Mahir Faysal, Sharmin Rima, Md. Anwer Hossain, Abdullah Al Mamun. Project administration: Mohammad Bellal Hossain, Md. Zakiul Alam, Md. Syful Islam, Shafayat Sultan, Md. Mahir Faysal, Sharmin Rima, Md. Anwer Hossain, Abdullah Al Mamun. Resources: Mohammad Bellal Hossain, Md. Zakiul Alam, Md. Syful Islam, Shafayat Sultan, Md. Mahir Faysal, Sharmin Rima, Md. Anwer Hossain, Abdullah Al Mamun. Software: Md. Zakiul Alam, Abdullah Al Mamun. Supervision: Mohammad Bellal Hossain, Md. Zakiul Alam, Md. Syful Islam, Shafayat Sultan, Md. Mahir Faysal, Sharmin Rima, Md. Anwer Hossain, Abdullah Al Mamun. Validation: Mohammad Bellal Hossain, Md. Zakiul Alam, Shafayat Sultan. Visualization: Mohammad Bellal Hossain, Md. Zakiul Alam, Shafayat Sultan. Writing – original draft: Mohammad Bellal Hossain, Md. Zakiul Alam, Shafayat Sultan. Writing – review & editing: Mohammad Bellal Hossain, Md. Zakiul Alam, Md. Syful Islam, Shafayat Sultan, Md. Mahir Faysal, Sharmin Rima, Md. Anwer Hossain, Abdullah Al Mamun.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bangladesh Medical Research Council-BMRC (Registration No. 39131012021).

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all the study participants.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will make the raw data supporting this article’s conclusions available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants in this study and the data collectors for their contributions during the challenging COVID-19 pandemic.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmed, S. Hoque, M. E., Sarker, A. R., Sultana, M., Islam, Z., Gazi, R., & Khan, J. A. M. Willingness-to-pay for community-based health insurance among informal workers in urban bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Making Sense of Rumor and Fear. Medical Anthropology 2020, 39, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M. & Hossain, A. What is the extent of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh? : A cross-sectional rapid national survey. MedRxiv 2121. medRxiv:2021.02.17.21251917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, R. Islam, M. S., Pranta, M. U. R., Rahman, Q. M., Rahman, M., Pardhan, S., Driscoll, R., Hossain, S., & Sikder, M. T. Understanding the determinants of COVID-19 vaccination intention and willingness to pay: findings from a population-based survey in Bangladesh. BMC Infectious Diseases 2021, 21, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBS. Report on Bangladesh Sample Vital Statistics. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- BBS. Final Report On Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2016.

- Berghea, F., Berghea, C. E., Abobului, M., & Vlad, V. M. Willingness to Pay for a for a Potential Vaccine Against SARS-CoV-2 / COVID-19 Among Adult Persons. Research Square 2020, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, T. Mahmud, I., & Alam, B. Usability Analysis of Sms Alert System for Immunization in the Context of Bangladesh. International Journal of Research in Engineering and Technology 2013, 02, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catma, S. & Varol, S. Willingness to Pay for a Hypothetical COVID-19 Vaccine in the United States: A Contingent Valuation Approach. Vaccines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, A.A. García, L.Y. Willingness to Pay for a COVID-19 Vaccine. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2021, 19, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, A. Simas, C., Karafillakis, E., Paterson, P., & Larson, H. J. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: a large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. The Lancet 2020, 396, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Godói, I. P. Tadeu Rocha Sarmento, T., Afonso Reis, E., Peres Gargano, L., Godman, B., de Assis Acurcio, F., … Mariano Ruas, C. Acceptability and willingness to pay for a hypothetical vaccine against SARS CoV-2 by the Brazilian consumer: a cross-sectional study and the implications. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research 2021, 22, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbarazi, I. Devlin, N. J., Katsaiti, M. S., Papadimitropoulos, E. A., Shah, K. K., & Blair, I. The effect of religion on the perception of health states among adults in the United Arab Emirates: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L. Y. & Cerda, A. A. Contingent assessment of the COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccine 2020, 38, 5424–5429. [Google Scholar]

- Hajj Hussein, I. Chams, N., Chams, S., El Sayegh, S., Badran, R., Raad, M., Gerges-Geagea, A., Leone, A., & Jurjus, A. Vaccines Through Centuries: Major Cornerstones of Global Health. Frontiers in Public Health 2015, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harapan, H. Fajar, J. K., Sasmono, R. T., & Kuch, U. Dengue vaccine acceptance and willingness to pay. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics 2017, 13, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harapan, H. Wagner, A. L., Yufika, A., Winardi, W., Anwar, S., Gan, A. K., Setiawan, A. M., Rajamoorthy, Y., Sofyan, H., Vo, T. Q., Hadisoemarto, P. F., Müller, R., Groneberg, D. A., & Mudatsir, M. Willingness-to-pay for a COVID-19 vaccine and its associated determinants in Indonesia. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics 2020, 16, 3074–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. B. Alam, M. Z., Islam, M. S., Sultan, S., Faysal, M. M., Rima, S., Hossain, M. A., Mahmood, M. M., Kashfi, S. S., Mamun, A. Al, Monia, H. T., & Shoma, S. S. Population-Level Preparedness About Preventive Practices Against Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Adults in Bangladesh. Frontiers in Public Health 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z. Chang, J., Yue, D., Fang, H., Meng, Q., & Zhang, Y. Determinants of willingness to pay for self-paid vaccines in China. Vaccine 2014, 32, 4471–4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute, N. C. Theory at a Glance: A Guide For Health Promotion Practice 2005, 5. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24443779.

- Islam, S. M. S., Lechner, A., Ferrari, U., Seissler, J., Holle, R., & Niessen, L. W. Mobile phone use and willingness to pay for SMS for diabetes in Bangladesh. Journal of Public Health (United Kingdom) 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, R. Mahmud, I., Chowdhury, M. T. H., Vinnakota, D., Jahan, S. S., Siddika, N., Isha, S. N., Nath, S. K., & Apu, E. H. COVID-19 vaccination intent and willingness to pay in Bangladesh : a cross-sectional study. Vaccines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-Y. Sagiraju, H. K. R., Russell, L. B., & Sinha, A. Willingness-To-Pay for Vaccines in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Annals of Vaccines and Immunization 2014, 1, 1001. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, H. J. Schulz, W. S., Tucker, J. D., & Smith, D. M. D. Measuring Vaccine Confidence : Introducing a Global Vaccine Confidence Index. PLOS Currents Outbreaks 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. Hu, Z., Zhao, Q., Alias, H., Danaee, M., & Wong, L. P. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: A nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2020, 14, e0008961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P. O’Halloran, A., Kennedy, E. D., Williams, W. W., Kim, D., Fiebelkorn, A. P., Donahue, S., & Bridges, C. B. Awareness among adults of vaccine-preventable diseases and recommended vaccinations, United States, 2015. Vaccine 2017, 35, 3104–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuestion, M. Gnawali, D., Kamara, C., Kizza, D., Mambu-Ma-Disu, H., Mbwangue, J., & Quadros, C. Creating Sustainable Financing And Support For Immunization Programs In Fifteen Developing Countries. Health Affairs 2011, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoHFW. Bangladesh National Health Accounts 1997-2012; 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, T. & Trapero-Bertran, M. The influence of education on the access to childhood immunization: The case of Spain. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudatsir, M. Anwar, S., Fajar, J. K., Yufika, A., Ferdian, M. N., Salwiyadi, S., Imanda, A. S., Azhars, R., Ilham, D., Timur, A. U., Sahputri, J., Yordani, R., Pramana, S., Rajamoorthy, Y., Wagner, A. L., Jamil, K. F., & Harapan, H. Willingness-to-pay for a hypothetical Ebola vaccine in Indonesia: A cross-sectional study in Aceh. F1000Research 2020, 8, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann-Böhme, S. Varghese, N. E., Sabat, I., Barros, P. P., Brouwer, W., van Exel, J., Schreyögg, J., & Stargardt, T. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. European Journal of Health Economics 2020, 21, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamoorthy, Y. Radam, A., Taib, N. M., Rahim, K. A., Munusamy, S., Wagner, A. L., Mudatsir, M., Bazrbachi, A., & Harapan, H. Willingness to pay for hepatitis B vaccination in Selangor, Malaysia: A cross-sectional household survey. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S. Woldemichael, A., Mirzaei, M., Mohammadi, S., & Karami Matin, B. Mothers’ willingness to accept and pay for vaccines to their children in western Iran: A contingent valuation study. BMC Pediatrics 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam M, Anwar S, Yufika A, Fahriani M, Husnah M, Kusuma HI, Raad R, Khiri NM, Abdalla RY, Adam RY, Ismaeil MI, Ismail AY, Kacem W, Teyeb Z, Aloui K, Hafsi M, Dahman NBH, Ferjani M, Deeb D, Emad D, Sami FS, Abbas KS, Monib FA, R S, Panchawagh S, Sharun K, Anandu S, Gachabayov M, Haque MA, Emran TB, Wendt GW, Ferreto LE, Castillo-Briones MF, Inostroza-Morales RB, Lazcano-Díaz SA, Ordóñez-Aburto JT, Troncoso-Rojas JE, Balogun EO, Yomi AR, Durosinmi A, Adejumo EN, Ezigbo ED, Arab-Zozani M, Babadi E, Kakemam E, Ullah I, Malik NI, Dababseh D, Rosiello F, Enitan SS. Willingness-to-pay for COVID-19 vaccine in ten low-middle-income countries in Asia, Africa and South America: A cross-sectional study. Narra J. 2022, 2, e74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M. Dababseh, D., Eid, H., Al-Mahzoum, K., Al-Haidar, A., Taim, D., Yaseen, A., Ababneh, N. A., Bakri, F. G., & Mahafzah, A. High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries. Vaccines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, A. R. Islam, Z., Sultana, M., Sheikh, N., Mahumud, R. A., Taufiqul Islam, M., Van Der Meer, R., Morton, A., Khan, A. I., Clemens, J. D., Qadri, F., & Khan, J. A. M. Willingness to pay for oral cholera vaccines in urban Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, K.-D. O. An Assessment of Muslims Reactions to The Immunization of Children in Northern Nigeria. Medical Journal of Islamic World Academy of Sciences 2014, 22, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Lyu, Y., Zhang, H., Jing, R., Lai, X., Feng, H., Knoll, M. D., & Fang, H. Willingness to pay and financing preferences for COVID-19 vaccination in China. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1968–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L. P. Alias, H., Wong, P. F., Lee, H. Y., & AbuBakar, S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics 2020, 16, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worasathit, R. Wattana, W., Okanurak, K., Songthap, A., Dhitavat, J., & Pitisuttithum, P. Health education and factors influencing acceptance of and willingness to pay for influenza vaccination among older adults. BMC Geriatrics 2015, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajacova, A. & Lawrence, E. M. The Relationship between Education and Health: Reducing Disparities Through a Contextual Approach. Annual Review of Public Health 2018, 39, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).