Submitted:

16 August 2024

Posted:

16 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area: The City of Madrid

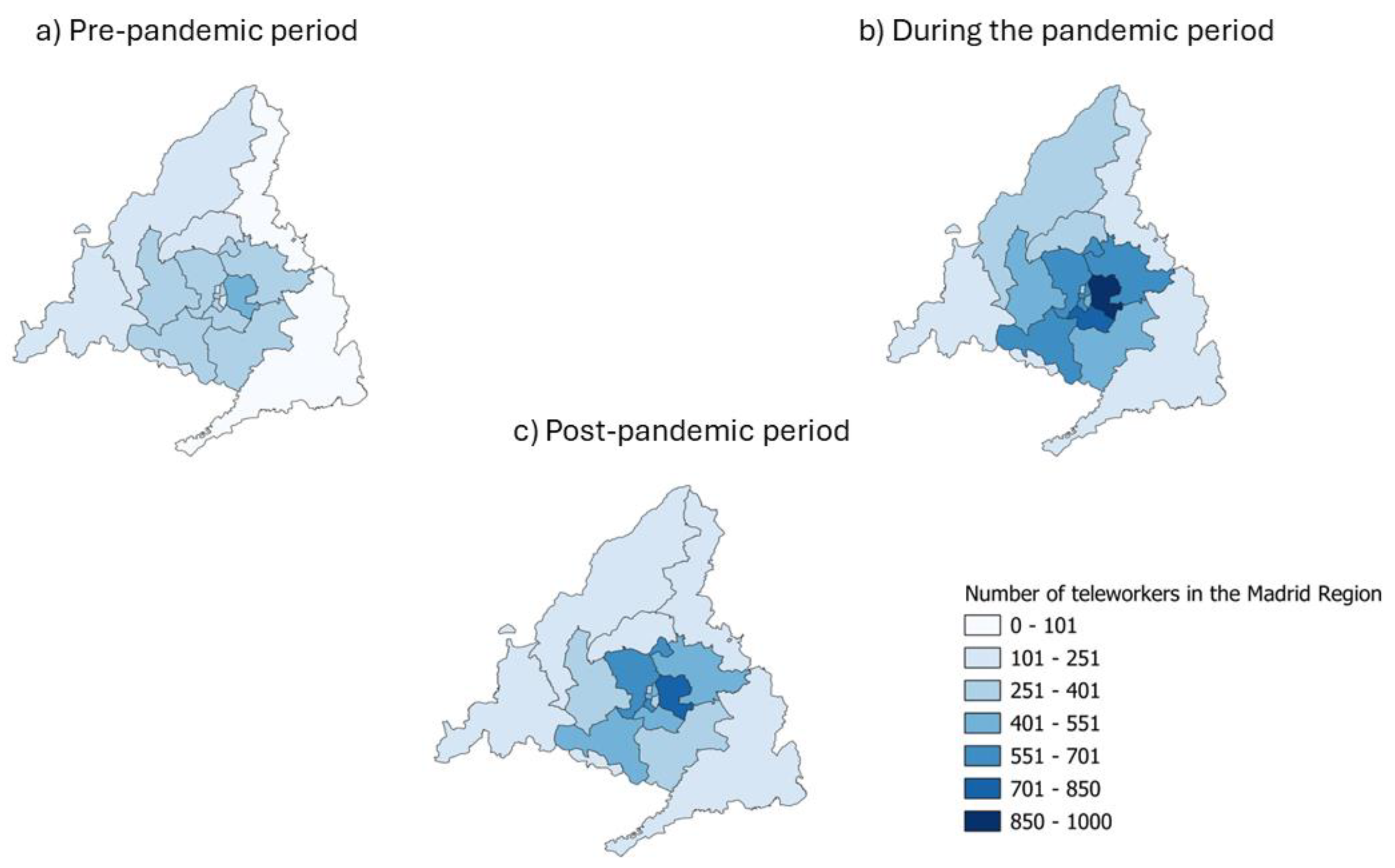

2.2. Who Teleworks in the Madrid Region? A Teleworker Profile

2.3. Methods

2.4. Data Collection

3. Results

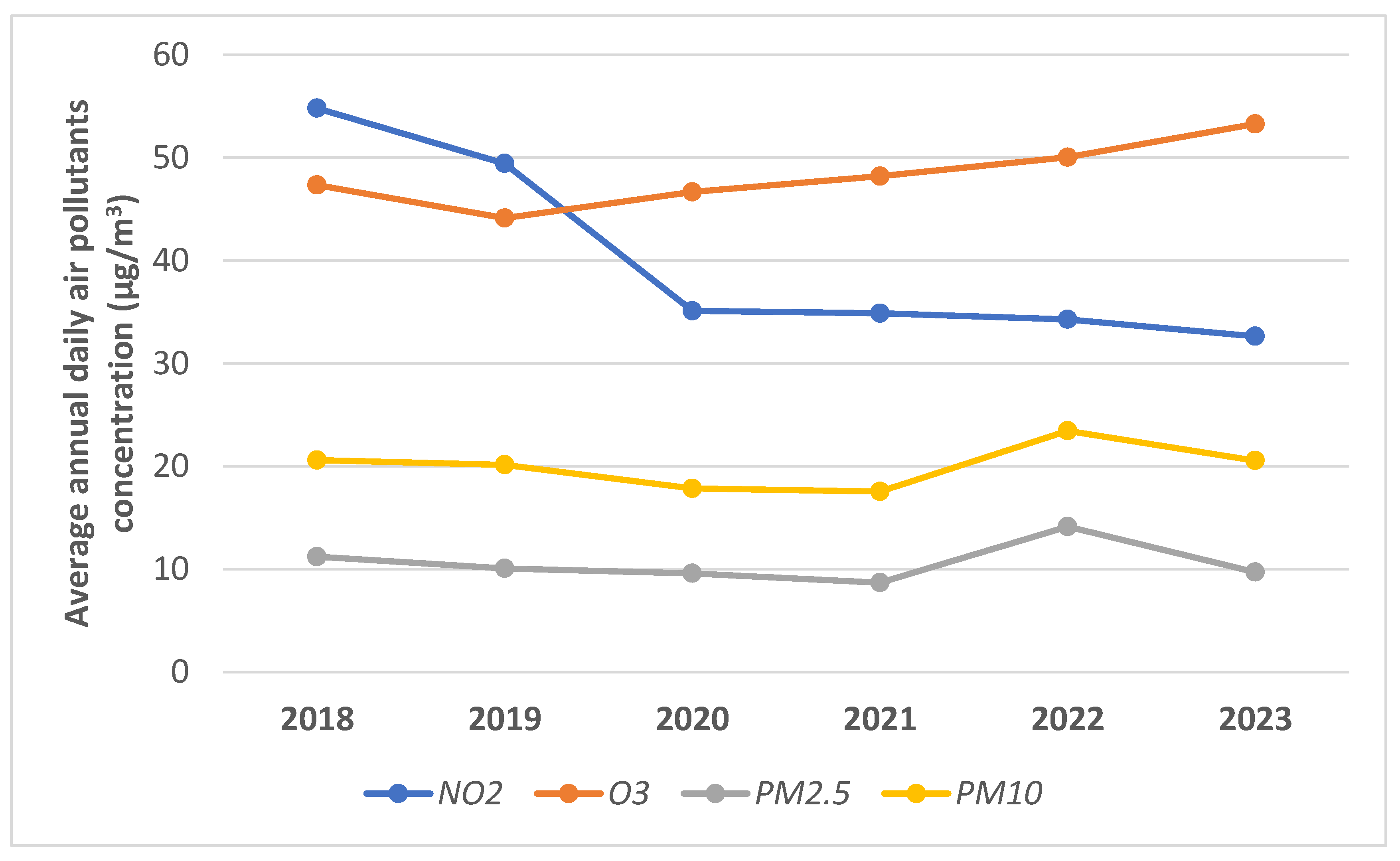

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Correlation Analysis

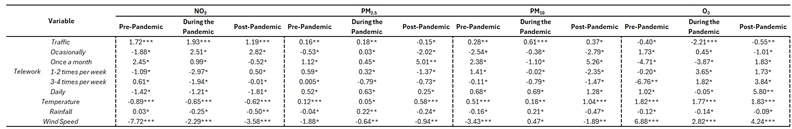

3.3. Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EEA Europe’s Air Quality Status 2023. 2023.

- Ramacher, M.O.P.; Badeke, R.; Fink, L.; Quante, M.; Karl, M.; Oppo, S.; Lenartz, F.; Dury, M.; Matthias, V. Assessing the Effects of Significant Activity Changes on Urban-Scale Air Quality across Three European Cities. Atmos. Environ. X 2024, 22, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Sousa, P.M.; Durão, R.M.; Ramos, A.M.; Salvador, P.; Linares, C.; Díaz, J.; Trigo, R.M. Saharan Dust Intrusions in the Iberian Peninsula: Predominant Synoptic Conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis, J.E.; Morales, J.R.; Zaror, C.A.; Inzunza, J.C. A Study of the Particulate Matter PM10 Composition in the Atmosphere of Chillán, Chile. Chemosphere 2004, 54, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Viana, M.M.; Rodriguez, S.; Artiñano, B.; Salvador, P.; Garcia Do Santos, S.; Fernandez Patier, R.; Ruiz, C.R.; De La Rosa, J.; et al. Speciation and Origin of PM10 and PM2.5 in Spain. J. Aerosol Sci. 2004, 35, 1151–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Qian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, N. Analyzing the Contribution of Human Mobility to Changes in Air Pollutants: Insights from the COVID-19 Lockdown in Wuhan. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, N.; Arce, R. Understanding Per-Trip Commuting CO2 Emissions: A Case Study of the Technical University of Madrid. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 96, 102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shi, B.; Shi, Y.; Marvin, S.; Zheng, Y.; Xia, G. Air Pollution Dispersal in High Density Urban Areas: Research on the Triadic Relation of Wind, Air Pollution, and Urban Form. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 54, 101941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urso, P.; Cattaneo, A.; Garramone, G.; Peruzzo, C.; Cavallo, D.M.; Carrer, P. Identification of Particulate Matter Determinants in Residential Homes. Build. Environ. 2015, 86, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J. Tropospheric Ozone: Seasonal Behavior, Trends, and Anthropogenic Influence. In Journal of Geophysical Research; 1985; Vol. 90, pp. 463–482.

- Jacob, D.J.; Heikes, B.G.; Fan, S.M.; Logan, J.A.; Mauzerall, D.L.; Bradshaw, J.D.; Singh, H.B.; Gregory, G.L.; Talbot, R.W.; Blake, D.R.; et al. Origin of Ozone and NOx in the Tropical Troposphere: A Photochemical Analysis of Aircraft Observations over the South Atlantic Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1996, 101, 24235–24250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hak, C.; Larssen, S.; Randall, S.; Guerreiro, C.; Denby, B.; Horálek, J. Traffic and Air Quality - Contribution of Traffic to Urban Air Quality in European Cities. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kampa, M.; Castanas, E. Human Health Effects of Air Pollution. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 151, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Batterman, S. Air Pollution and Health Risks Due to Vehicle Traffic. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 450–451, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehm, J.; Room, R.; Monteiro, M.; Gmel, G.; Graham, K.; Rehn, N.; Sempos, C.T.; Frick, U.; Jernigan, D.; Ezzati, M.; et al. World Health Organization Report Report Part Title: Comparative Quantification of Health Risks Report Subtitle: Global and Regional Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risk Factors Report Editor(S). World Heal. Organ. 2004, 729. [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri, G.; Crisci, A.; Tartaglia, M.; Toscano, P.; Gioli, B. A Statistical Model to Assess Air Quality Levels at Urban Sites. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 2015, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, I.A.; García, M.Á.; Sánchez, M.L.; Pardo, N.; Fernández-Duque, B. Key Points in Air Pollution Meteorology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, J.G.; Williams, M.L. Acid Rain: Chemistry and Transport. Environ. Pollut. 1988, 50, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrid City Council Action Protocol for Episodes of Nitrogen Dioxide Pollution in the City of Madrid; 2016; Vol. 36;

- Bailey, D.E.; Kurland, N.B. A Review of Telework Research: Findings, New Directions, and Lessons for the Study of Modern Work. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A. Teleworking in the Context of the Covid-19 Crisis. Sustain. 2020, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOE Royal Decree 463/2020, of March 14, Declaring a State of Alarm for the Management of the Health Crisis Situation Caused by COVID-19. Off. State Gazzette 2020, 67, 25390–25400.

- Bhatti, A.; Akram, H.; Basit, H.M.; Khan, A.U.; Naqvi, S.M.R.; Bilal, M. E-Commerce Trends During Covid-19. Int. J. Futur. Gener. Commun. Netw. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat E-Commerce Statistics for Individuals Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=E-commerce_statistics_for_individuals.

- MINECO Teleworking in Spain before, during and after the Pandemic. Available online: https://www.ontsi.es/es/publicaciones/el-teletrabajo-en-espana (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- BOE Law 10/2021, of July 2, of Remote Working. Boletín Of. del Estado, 2021; 82540–82583.

- Metz, D. The Myth of Travel Time Saving. Transp. Rev. 2008, 28, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.P.; Sánchez, A.M.; De Luis Carnicer, M.P.; Jiménez, M.J.V. The Environmental Impacts of Teleworking: A Model of Urban Analysis and a Case Study. Manag. Environ. Qual. An Int. J. 2004, 15, 656–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvile, R.N.; Hutchinson, E.J.; Mindell, J.S.; Warren, R.F. The Transport Sector as a Source of Air Pollution. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 1537–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, J.P. Analysing Road Traffic Influences on Air Pollution: How to Achieve Sustainable Urban Development. Transp. Rev. 2000, 20, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, R.; Neeta, S.; Geeta, G. Air Pollution Due to Road Transportation in India: A Review on Assessment and Reduction Strategies. J. Environ. Res. Dev. 2013, 8, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Forehead, H.; Huynh, N. Review of Modelling Air Pollution from Traffic at Street-Level - The State of the Science. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 241, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañuelos-Gimeno, J.; Sobrino, N.; Arce, R. Effects of Mobility Restrictions on Air Pollution in the Madrid Region during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Post-Pandemic Periods. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.T.; Branco, P.T.B.S.; Sousa, S.I.V. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Air Quality: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurostat Rise in EU Population Working from Home Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20221108-1.

- Sampath, S.; Saxena, S.; Mokhtarian, P.L. The Effectiveness of Telecommuting as a Transportation Control Measure. UC Berkeley Univ. Calif. Transp. Cent. 1991, 15, 250–260. [Google Scholar]

- Ravalet, E.; Rérat, P. Teleworking: Decreasing Mobility or Increasing Tolerance of Commuting Distances? Built Environ. 2019, 45, 582–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitou, E.; Horvath, A. Transportation Choices and Air Pollution Effects of Telework. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2006, 12, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, S.; Mokhtarian, P.L.; Salomon, I. Does Telecommuting Reduce Vehicle-Miles Traveled? An Aggregate Time Series Analysis for the U.S. Transportation (Amst). 2005, 32, 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, M.; Safirova, E. A Review of the Literature on Telecommuting and Its Implications for Vehicle Travel and Emissions. Resour. Futur. 2004, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, B.E.; Henderson, D.K.; Mokhtarian, P.L. The Travel and Emissions Impacts of Telecommuting for the State of California Telecommuting Pilot Project. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 1996, 4, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, A.; Langemeyer, J.; Codina, X.; Gilabert, J.; Guilera, N.; Vidal, V.; Segura, R.; Vives, M.; Villalba, G. A Take-Home Message from COVID-19 on Urban Air Pollution Reduction through Mobility Limitations and Teleworking. npj Urban Sustain. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, E.D.V.; Motte-Baumvol, B.; Chevallier, L.B.; Bonin, O. Does Working from Home Reduce CO2 Emissions? An Analysis of Travel Patterns as Dictated by Workplaces. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 83, 102338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparrós Ruiz, A. Factors Determining Teleworking before and during COVID-19: Some Evidence from Spain and Andalusia. Appl. Econ. Anal. 2022, 30, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anik, M.A.H.; Habib, M.A. COVID-19 and Teleworking: Lessons, Current Issues and Future Directions for Transport and Land-Use Planning. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostettler Macias, L.; Ravalet, E.; Rérat, P. Potential Rebound Effects of Teleworking on Residential and Daily Mobility. Geogr. Compass 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akioui, A.; Monzon, A. Teleworking and Its Impacts on Mobility in the Region of Madrid. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 71, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2024.

- CRTM Regional Transport Consortium of the Community of Madrid Available online:. Available online: https://www.crtm.es/ (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- OMM Report of the Metropolitan Mobility Observatory for 2020 and Progress 2021. 2020.

- Madrid City Council Air Quality Annual Report 2019. Madrid City Counc. 2019, 1, 81.

- Levinson, D.M.; Kumar, A. Density and the Journey to Work. Growth Change 1997, 28, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarriño-Ortiz, J.; Gómez, J.; Soria-Lara, J.A.; Vassallo, J.M. Analyzing the Impact of Low Emission Zones on Modal Shift. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckerman, B.; Jerrett, M.; Brook, J.R.; Verma, D.K.; Arain, M.A.; Finkelstein, M.M. Correlation of Nitrogen Dioxide with Other Traffic Pollutants near a Major Expressway. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente, C. Otra Vez La Calima: Vuelve La Lluvia de “Barro” a Andalucía En Un Cierre de Marzo Muy Húmedo. eldiario.es 2022.

- Transport Research Centre (TRANSyT-UPM), E.; MORES-CM Project. Strategies for a Resilient and Sustainable Mobility of Passengers and Goods Post-COVID in the Community of Madrid. Available online: http://e.mores-cm.transyt-projects.es/ (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- INE Survey on Equipment and Use of Information and Communication Technologies in Households 2021. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dynt3/inebase/index.htm?padre=8320&capsel=8320 (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Mukaka, M.M. Statistics Corner: A Guide to Appropriate Use of Correlation Coefficient in Medical Research. Malawi Med. J. 2012, 24, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J. Changes in the Relationship between Particulate Matter and Surface Temperature in Seoul from 2002-2017. Atmosphere (Basel). 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, Z.H.; Kim, K.H.; Song, S.K. Long-Term Trend in NO2 and NOx Levels and Their Emission Ratio in Relation to Road Traffic Activities in East Asia. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 3120–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hak, C.; Larssen, S.; Randall, S.; Guerreiro, C.; Denby, B.; Horálek, J. Traffic and Air Quality - Contribution of Traffic to Urban Air Quality in European Cities. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- von Schneidemesser, E.; Sibiya, B.; Caseiro, A.; Butler, T.; Lawrence, M.G.; Leitao, J.; Lupascu, A.; Salvador, P. Learning from the COVID-19 Lockdown in Berlin: Observations and Modelling to Support Understanding Policies to Reduce NO2. Atmos. Environ. X 2021, 12, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañuelos-Gimeno, J.; Blanco, A.; Díaz, J.; Linares, C.; López, J.A.; Navas, M.A.; Sánchez-Martínez, G.; Luna, Y.; Hervella, B.; Belda, F.; et al. Air Pollution and Meteorological Variables’ Effects on COVID-19 First and Second Waves in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 20, 2869–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañuelos-Gimeno, J.; Sobrino, N.; Arce, R. Efectos Del Tráfico En La Contaminación Atmosférica. In Evidencia Empírica En Las Olas de COVID-19 En La Ciudad de Madrid. In Proceedings of the Congreso de Ingenieria del Transporte CIT: Revolucionando el transporte; 2023; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- New Zeland Ministry of Environment Nitrogen Dioxide. Available online: https://environment.govt.nz/facts-and-science/air/air-pollutants/nitrogen-dioxide-effects-health/ (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Querol, X.; Viana, M.; Alastuey, A.; Amato, F.; Moreno, T.; Castillo, S.; Pey, J.; de la Rosa, J.; Sánchez de la Campa, A.; Artíñano, B.; et al. Source Origin of Trace Elements in PM from Regional Background, Urban and Industrial Sites of Spain. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 7219–7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheel, H.E.; Areskoug, H.; Geiß, H.; Gomiscek, B.; Granby, K.; Haszpra, L.; Klasinc, L.; Kley, D.; Laurila, T.; Lindskog, A.; et al. On the Spatial Distribution and Seasonal Variation of Lower-Troposphere Ozone over Europe. J. Atmos. Chem. 1997, 28, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodakarami, J.; Ghobadi, P. Urban Pollution and Solar Radiation Impacts. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.N.; Sobrino, N.; Vassallo, J.M. Considering the City Context in Weighting Sustainability Criteria for Last-Mile Logistics Solutions. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akioui, A.; Monzon, A. Teleworking and Its Impacts on Mobility in the Region of Madrid. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 71, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, F. Gaining the Air Quality and Climate Benefit for Telework. World Resour. Inst. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kitou, E.; Horvath, A.; Masanet, E.; Student, G.; Professor, A. Putting in Perspective the Contribution of Transportation to the Environmental Effects of Telework. In Proceedings of the 81st Transportation Research Board Conference; 2002; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Cools, M.; Moons, E.; Wets, G. Assessing the Impact of Weather on Traffic Intensity. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2010, 2, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Tamurejo, A.; Herraez, B.R.; Agudo, M.L.M. Telework and the Limited Impact on Traffic Reduction – Case Study Madrid (Spain). Acta Logist. 2023, 10, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pre-pandemic | During the pandemic | Post-Pandemic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage* (%) | 26.41% | 48.47% | 39.07% |

| Age (mean, years) | 44.57 | 43.16 | 42.36 |

| Gender | Mostly male M: 54.23% F: 45.77% |

Mostly female M: 48.33% F: 51.67% |

Equal distribution M: 49.75% F: 50.25% |

| Income | Medium 1,500 € - 3,000 € |

Medium 1,500 € - 3,000 € |

Medium 1,500 € - 3,000 € |

| Employment | Employee | Employee | Employee |

| House type | Apartment | Apartment | Apartment |

| Variable | Period | Daily Mean | Std. Deviation | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic (per thousand of vehicles) |

Pre-Pandemic | 17.60 | 2.91 | 10 | 23 |

| During the Pandemic | 13.76 | 3.08 | 6 | 19 | |

| After the Pandemic | 16.33 | 2.49 | 8 | 20 | |

| NO2 (µg/m3) |

Pre-Pandemic | 52.12 | 14.74 | 15 | 99 |

| During the Pandemic | 34.99 | 12.56 | 10 | 78.5 | |

| After the Pandemic | 33.45 | 10.82 | 14.5 | 71 | |

| PM2.5 (µg/m3) |

Pre-Pandemic | 10.64 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 25 |

| During the Pandemic | 9.13 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 27.5 | |

| After the Pandemic | 11.92 | 8.9 | 2.5 | 74 | |

| PM10 (µg/m3) |

Pre-Pandemic | 20.36 | 8.2 | 7 | 49.5 |

| During the Pandemic | 17.69 | 8.2 | 3 | 53.5 | |

| After the Pandemic | 22.00 | 14.35 | 5 | 125.5 | |

| O3 (µg/m3) |

Pre-Pandemic | 45.73 | 19.6 | 4.5 | 92 |

| During the Pandemic | 47.43 | 18.73 | 4.5 | 88.5 | |

| After the Pandemic | 51.66 | 19.68 | 6.29 | 90.08 | |

| Temperature (oC) | Pre-Pandemic | 15.9 | 7.51 | 4 | 31 |

| During the Pandemic | 15.8 | 7.17 | 0 | 30 | |

| After the Pandemic | 16.8 | 7.67 | 5 | 32 | |

| Rainfall (L/m2) |

Pre-Pandemic | 1.3 | 2.81 | 0 | 19 |

| During the Pandemic | 1.5 | 3.86 | 0 | 34 | |

| After the Pandemic | 0.98 | 2.49 | 0 | 19 | |

| Wind Speed (m/s) | Pre-Pandemic | 2.00 | 0.75 | 0 | 4 |

| During the Pandemic | 1.98 | 0.89 | 0 | 6 | |

| After the Pandemic | 2.12 | 0.97 | 1 | 6 |

| Traffic | NO2 | PM2.5 | PM10 | O3 | Temperature | Rainfall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic | 1.0000 | ||||||

| NO2 | 0.4500 | 1.0000 | |||||

| PM2.5 | -0.1997 | 0.2563 | 1.0000 | ||||

| PM10 | -0.0804 | 0.2153 | 0.8478 | 1.0000 | |||

| O3 | -0.2588 | -0.6031 | -0.0166 | 0.0857 | 1.0000 | ||

| Temperature | -0.3199 | -0.5424 | 0.2618 | 0.4692 | 0.6951 | 1.0000 | |

| Rainfall | 0.0632 | 0.0668 | -0.0926 | -0.1796 | -0.1222 | -0.1932 | 1.0000 |

| Wind speed | 0.0981 | -0.3361 | -0.3516 | -0.3470 | 0.2139 | -0.0592 | 0.1269 |

| Traffic | NO2 | PM2.5 | PM10 | O3 | Temperature | Rainfall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic | 1.0000 | ||||||

| NO2 | 0.5410 | 1.0000 | |||||

| PM2.5 | 0.1150 | 0.3078 | 1.0000 | ||||

| PM10 | 0.2017 | 0.3381 | 0.7928 | 1.0000 | |||

| O3 | -0.4633 | -0.7163 | -0.2152 | -0.1041 | 1.0000 | ||

| Temperature | -0.1338 | -0.4438 | 0.0430 | 0.1153 | 0.7392 | 1.0000 | |

| Rainfall | -0.0511 | -0.0701 | 0.2006 | 0.0747 | -0.0615 | -0.0703 | 1.0000 |

| Wind speed | -0.0728 | -0.2378 | -0.1381 | -0.0446 | 0.2323 | 0.1121 | -0.0185 |

| Traffic | NO2 | PM2.5 | PM10 | O3 | Temperature | Rainfall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic | 1.0000 | ||||||

| NO2 | 0.3888 | 1.0000 | |||||

| PM2.5 | -0.1824 | -0.0575 | 1.0000 | ||||

| PM10 | -0.0944 | -0.0050 | 0.9134 | 1.0000 | |||

| O3 | -0.2560 | -0.7390 | 0.2781 | 0.3111 | 1.0000 | ||

| Temperature | -0.2545 | -0.5082 | 0.5107 | 0.5454 | 0.7496 | 1.0000 | |

| Rainfall | 0.0686 | 0.0032 | -0.1214 | 0.1343 | -0.1392 | -0.1302 | 1.0000 |

| Wind speed | -0.0104 | -0.3295 | -0.0686 | -0.0931 | 0.2368 | 0.0276 | -0.1154 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).