1. Introduction

Amidst the backdrop of globalization and urbanization, China's urban and rural development patterns, as well as landscape features, are undergoing profound transformations, indicating an inevitable shift. China emphasizes the integration of emotional bonds within urbanization strategies, advocating for a vision where residents can connect with their surroundings and recall nostalgic sentiments, thus enhancing the evaluative criteria of urban development quality. In efforts to drive rural revitalization through tourism, scholars have directed their attention towards various aspects such as the perception of rural tourism destination offerings, stakeholder involvement, and sustainable social and cultural development[

1,

2,

3]. However, there remains a relatively limited analysis of the emotional characteristics of indigenous populations within the context of reconstructing and transforming rural tourism destinations, with even less attention given to the psychological and emotional traits of original inhabitants in suburban historical and cultural villages. As suburban historical and cultural villages are being transformed into tourist destinations,, research on livelihoods, human-land conflicts, emotional attitudes, and community sustainability has become essential[

4]. The field of tourism studies is witnessing increasing sophistication in the exploration of the intricate "man-land" relationships among community residents, tourists, and spatial elements within the communal tourism landscape[

5,

6]. This progression sets a foundation for delving into the psychological cognitive mechanisms of community residents in suburban historical and cultural villages.

The update and spatial reconstruction of suburban historical and cultural villages resulting from urban expansion represent a global concern[

7]. The boundaries between urban and rural areas are increasingly blurred, giving rise to a distinctive structure that embodies functions and development features characteristic of both urban and rural areas. This phenomenon is commonly referred to in literature as off-town areas, rural-urban fringe or suburban villages[

8]. The update of suburban historical and cultural villages pertains to the modernization and reconstruction of their landscape, spatial environment or architectural design. Furthermore, the appeal and resilience of suburban rural tourist destinations are further bolstered through continuous updates in modern media operations and marketing methods[

4]. Against this backdrop, different rural tourism landscapes continue to collide and merge, leading to the transplantation of rural tourism landscape imagery and the transformation of place landscape culture. Despite the voices from various sectors calling for the preservation of place landscape culture[

9,

10], what are the residents' emotional responses to the changes in rural tourism landscapes and tourism effects? What are the characteristics of their psychological cognitive mechanisms and processes? This necessitates a profound and meticulous examination. Therefore, this article takes the suburban historical and cultural village in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia as an example, using a more rigorous experimental and questionnaire method combined research approach, by constructing a model of residents' nostalgia, collective memory, subjective well-being, tourism effects and place identity, to explore the emotional characteristics and cognitive mechanisms of residents in the suburban historical and cultural village, thereby sparking reflection on the traditional spatial reconstruction of suburban rural tourist destinations, with the aim of providing theoretical basis and practical reference for the spatial reshaping of rural tourist destinations and the evolution of tourism landscape culture.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Nostalgia and Collective Memory

Nostalgia refers to an individual's emotional attachment to past experiences, including people, places, and events from their youth[

11]. With the current trend in nostalgia research, there is a growing focus on exploring its connection to outer space. Lowenthal (1975) pioneered the conceptualization of "nostalgia" through the lens of geography[

12]. British psychologists regard nostalgia as a multifaceted emotional tapestry woven from an individual's poignant ties to past individuals, locales, and experiences pivotal to their development[

11]. Subsequent scholarly work has underscored the pivotal role that space and place play in the construction of nostalgia, solidifying its standing as a critical domain within the realm of cultural geography[

13]. The exploration of nostalgia in modern and contemporary China has progressed through various stages, consistently set against the backdrop of rapid urbanization. This reflects a profound contemplation on the quality and pace of urbanization[

14].

In the mid-19th century, with the rapid progression of urban-rural migration, the collective spatial migration behavior of indigenous people became a focal point in studies on nostalgia. Nostalgic landscapes have been demonstrated to play a significant role in shaping collective memory[

15]. Collective memory, alternatively known as group memory, encapsulates the memories that are both generated and communally shared within a group[

16]. It acts as a central emotional nexus for individual memories that span across past and present, harmoniously merging temporal and spatial dimensions and fulfilling contemporary societal requirements[

17]. The environment can evoke memories among residents in communities of tourism destination; however, this association extends beyond mere "home" evoking the genuine essence of "home" within individuals[

18]. Nostalgia and memory are somewhat contradictory; while nostalgia represents forgetting aspects of the past, memory is continuously constructing and influencing our consciousness and relationships with both present circumstances and future prospects[

19,

20]. In situations where individuals' recollections of their living environments and upbringing are fragmented, there exists a unified nature between subject's nostalgia and collective memory. This cohesion accentuates the positive correlation between them[

21]. Grounded in this understanding, the subsequent hypothesis is posited:

H1: A positive correlation exists between the nostalgia and collective memory of residents in tourist destinations.

2.2. Collective Memory, Subjective Well-Being and Place Identity

2.2.1. Collective Memory and Subjective Well-Being

Diverse academic fields offer varied interpretations of subjective well-being, a multifaceted construct that includes elements of happiness, life quality and satisfaction[

22]. Shin & Johnson articulated subjective well-being as an all-encompassing evaluation of life quality through personally relevant criteria, a definition that has been expanded and refined by subsequent research[

23]. According to Diener[

24], subjective well-being is an individual's holistic and relatively stable evaluation of their own life quality against self-defined standards. Subjective well-being has emerged as a significant focus in the study of tourism and leisure behavior models and serves as a crucial dimension for evaluating the quality of tourism development. The connotation of subjective well-being includes a tendency towards individualism; however, the prevailing perspective on subjective well-being tends to shift from individual perception to collective perception[

25,

26]. Consequently, collective emotions and behaviors underpin and shape the subjective well-being of residents. Research indicates that past life events and environments can impact an individual's subjective well-being[

27,

28], with positive experiences leading to positive emotional outcomes while negative events result in negative emotional responses. Individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds exhibit varying perceptions and evaluations regarding subjective well-being[

29]. Subjective well-being aligns with individuals' emotional inclinations such as sense of accomplishment and satisfaction. Under specific conditions, it can yield positive effects through memory activation[

30]. Grounded in these insights, the ensuing hypothesis is introduced:

H2: A robust positive correlation exists between the collective memory and subjective well-being of residents in tourist destinations.

2.2.2. Collective Memory and Place Identity

Place identity is a multi-dimensional construct that encapsulates the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral facets of an individual's bond with their physical environment[

31]. The evolution of place identity is rooted in the concept of "place," which signifies the emotional significance attributed to locations, emphasizing a subjective evaluation of place[

32]. It underscores the significance of proactive individual participation in host-guest dynamics, indicating that place identity is reflective of the emotional attachment individuals extend to particular places[

33].

Memory retrieval serves as the cornerstone of place perception, forming the essential basis for developing cognition and attitudes towards a specific place[

34]. The study of collective memory is intricately linked to the establishment of place identity and national identity[

35]. Fortierposits that collective memory not only integrates individuals into a broader social context but also encompasses aspects such as past experiences, present perceptions, sense of place, nostalgia and belonging[

36]. Withers contends that collective memory is deeply rooted in place and closely associated with place identity[

37]. In their investigation on the collective memory and place identity among residents affected by disasters, the concept of "place displacement" is explored which refers to how changes in local environments threaten collective memory, thereby revealing latent aspects of place identity. The Activation of collective memory can evoke feelings related to one's connection with a specific place[

38]. Qian et al. further argue that collective memory acts as both a source and influencing factor for shaping place identity[

15]. Certain studies have explicitly identified collective memory as a precursor to both place attachment and the development of place identity[

39]. On the basis of this foundation, the subsequent hypothesis is introduced:

H3: Collective memory exerts a significant influence on the place identity of residents within tourist destinations.

2.2.3. Subjective Well-Being and Place Identity

Individuals are inclined to seek out and visit places that resonate with their personal affinities and identities, thereby enhancing their well-being through introspection and self-regulation [

22,

40]. Consequently, subjective well-being and place identity are driven by the same underlying factors. Maricchiolo et al. proposed that place identity and social relationships play a positive mediating role in social identity and happiness by examining the emotional characteristics of community residents[

41]. Theodori affirmed that higher levels of attachment among tourists lead to greater subjective well-being[

42]. Furthermore, a robust sense of attachment, intimacy and belongingness to their preferred personal or collective places (emotional components of place identity) are linked with elevated levels of subjective well-being. Knez & Eliasson also highlighted that place identity influences subjective well-being through both emotional and cognitive dimensions, even being capable of predicting happiness based on place identity[

43]. In a confirmatory analysis conducted by Wang & Bai[

44], in their case study on Xi'an Huifang validated the positive influence of place identity on subjective well-being. Similarly, more and more studies have proved through empirical studies that tourists' psychological well-being and subjective well-being will directly affect place identity[

45,

46]. Grounded in this evidence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Subjective well-being substantially influences the sense of belonging among residents in tourist destinations.

2.3. Tourism Effects, Collective Memory, Subjective Well-Being and Place Identity

Tourism is recognized as a method for creating collective memory at destinations, however, collective memory serves as a crucial tool for interpreting tourist destinations. The interplay between the impacts of tourism and collective memory is reciprocal[

47]. Tourism effects encompass various stakeholder groups, while collective memory represents a multidimensional construction process[

48]. The interaction between tourism and collective memory involves the activation, awakening, construction, and reinforcement of memories within the context of tourism. Additionally, it incorporates processes related to concealment, forgetting, and underlying mechanisms[

15]. Furthermore, tourism effects lead to alterations in the spatial structure of locations and can stimulate the collective memory among residents in tourist destinations[

49].

Subjective well-being, a construct influenced by emotions and cognition, unfolds in a manner that transcends the tangible aspects of an individual's environment, such as income, wealth and education, to reflect a more profound measure of one's overall well-being[

22,

50]. Well-being encompasses various aspects including psychological and emotional health as well as interpersonal relationships[

51]. The social benefits brought by tourism development are considered to be of great significance to the realization of the subject's emotional health and subjective well-being[

52]. Additionally, Darvishmotevali et al. propose that experiences related to learning, entertainment and aesthetics can further enhance individuals' sense of value thereby influencing their health and well-being[

53]. Leisure tourism not only enhances an individual's happiness but also contributes to the enhancement of tourists' subjective well-being while potentially improving the overall quality of life within the community[

54].

Amidst the phenomenon of "place dislocation", environmental transformations can jeopardize the bonds between individuals and their surroundings, thereby unmasking the intrinsic essence of place identity[

38]. People's emotional attachment to place meaning becomes stronger in response to environmental changes[

55]. Yang et al. have also delineated the attributes of place identity within the framework of tourism development in hometown by introducing the notion of "shopping cart" identity among overseas Chinese, wherein residents curate favorable elements from tourism development to shape their place identity[

56]. As tourism impacts materialize, there will be a heightened emotional attachment to residents' place identity. In light of these discussions above hypothesis is proposed:

H5: The effects of tourism development stimulate the collective memory of residents in tourist destinations.

H6: The effects of tourism development stimulate the subjective well-being of residents in tourist destinations.

H7: The effects of tourism development stimulate the sense of place identity among residents in tourist destinations.

2.4. Mediating and Chain Mediating Effect of Collective Memory and Subjective Well-Being

Memory is the result of social selection and place construction, embodying a vibrant and spatial manifestation of place and a spatialization of interpersonal relationships[

57]. Amidst the rapid spatial, communal and cultural shifts catalyzed by globalization, rural and urban environments are revered as vital vessels of collective memory[

15]. Collective memory acts as a pivotal intermediary, forging connections between the tangible realm of physical spaces and the intangible sphere of subjective perceptions. Moreover, subjective well-being is positively correlated with collective memory, both of which have a positive impact on place identity. Therefore, there is a structural mutual influence mechanism between nostalgia, tourism effects and place identity, mediated by collective memory and subjective well-being. Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H8: Subjective well-being plays a partial mediating role in the positive impact of collective memory on place identity;

H9: Collective memory plays a partial mediating role in the positive impact of subjective well-being on place identity;

H10: Collective memory plays a partial mediating role in the positive impact of tourism effects on place identity;

H11: Subjective well-being plays a partial mediating role in the positive impact of tourism effects on place identity;

H12: Collective memory and subjective well-being serve as chain mediators in the process of generating tourists' sense of place.

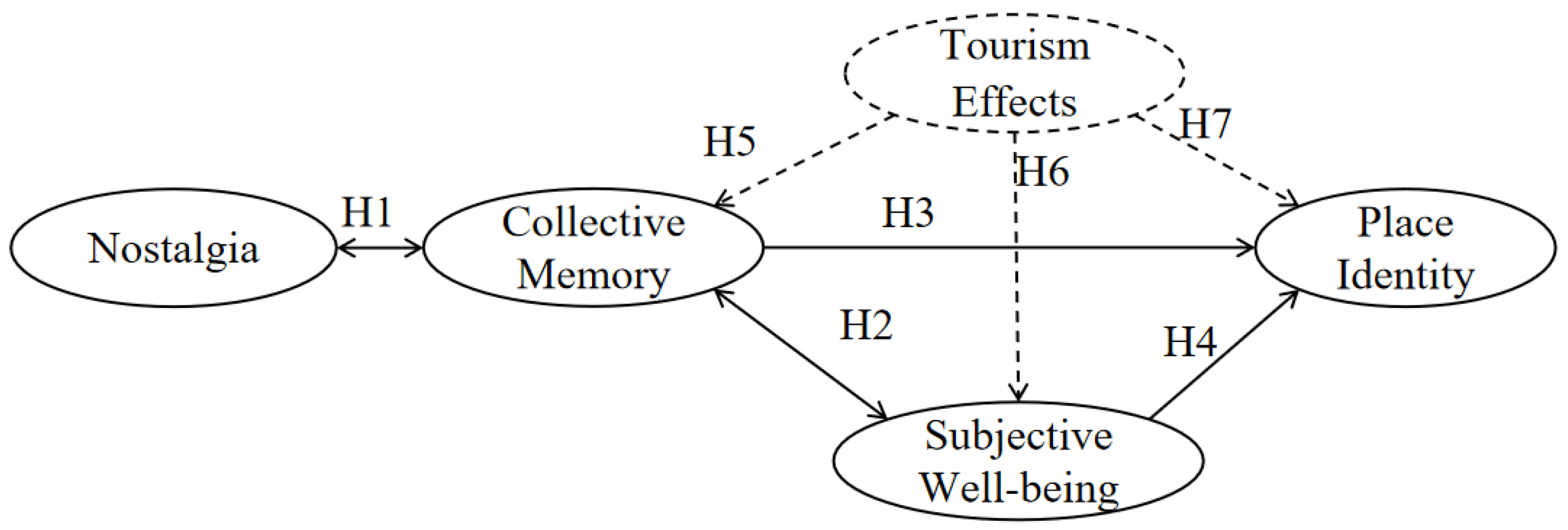

Figure 1.

Relationship model of nostalgia, collective memory , place identity and subjective well-being.

Figure 1.

Relationship model of nostalgia, collective memory , place identity and subjective well-being.

3. Research Design

3.1. Study Site

Naobao Village is situated in the suburbs of Hohhot, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China, covering an area of 9.8 square kilometers. It holds significance as one of the pivotal villages for China's new rural construction initiatives. Established by Han immigrants from Shanxi Province and local Mongolian residents, Naobao Village stands as a historical testament to ethnic integration and preservation of the rich culture inherent to both Mongolian and Shanxi regions. In recent years, with China's robust rural revitalization strategy gaining momentum, Naobao Village has introduced classical Chinese residential architecture alongside European architectural styles while transplanting elements of southern China's water towns' human landscape into northern arid region villages. Naobao Village has garnered rapid acclaim due to its burgeoning tourism sector. Its cultural and tourism industry platform generates annual revenue exceeding 1 billion yuan and attracts over 6 million tourists annually while creating more than 6,000 employment opportunities primarily for local community residents. The average annual income for villagers exceeds 50,000 yuan. In 2019, Naobao Village was selected among the inaugural batch of key rural tourism villages in China. Subsequently, it was recognized by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China as one of "China's Beautiful Leisure Villages" in 2022.

3.2. Research Design

Through interviews and field surveys in the case study area, it was discovered that significant changes had occurred in the living and landscape environment of residents in Nabao Village, evoking strong emotions related to the past, space and place while stimulating feelings of nostalgia and collective memory among residents. Under the combined effect of tourism and subjective well-being brought by the great change, residents continued to maintain a high level of place identity towards the new landscape environment. Nonetheless, to advance scientifically rigorous inquiry, this study seeks to verify: ① Whether landscape changes incite nostalgia and collective memory among residents; ② Whether such alterations promote an escalation in residents' subjective happiness; ③ Whether landscape modifications cultivate a positive sense of place, superseding negative emotional responses.

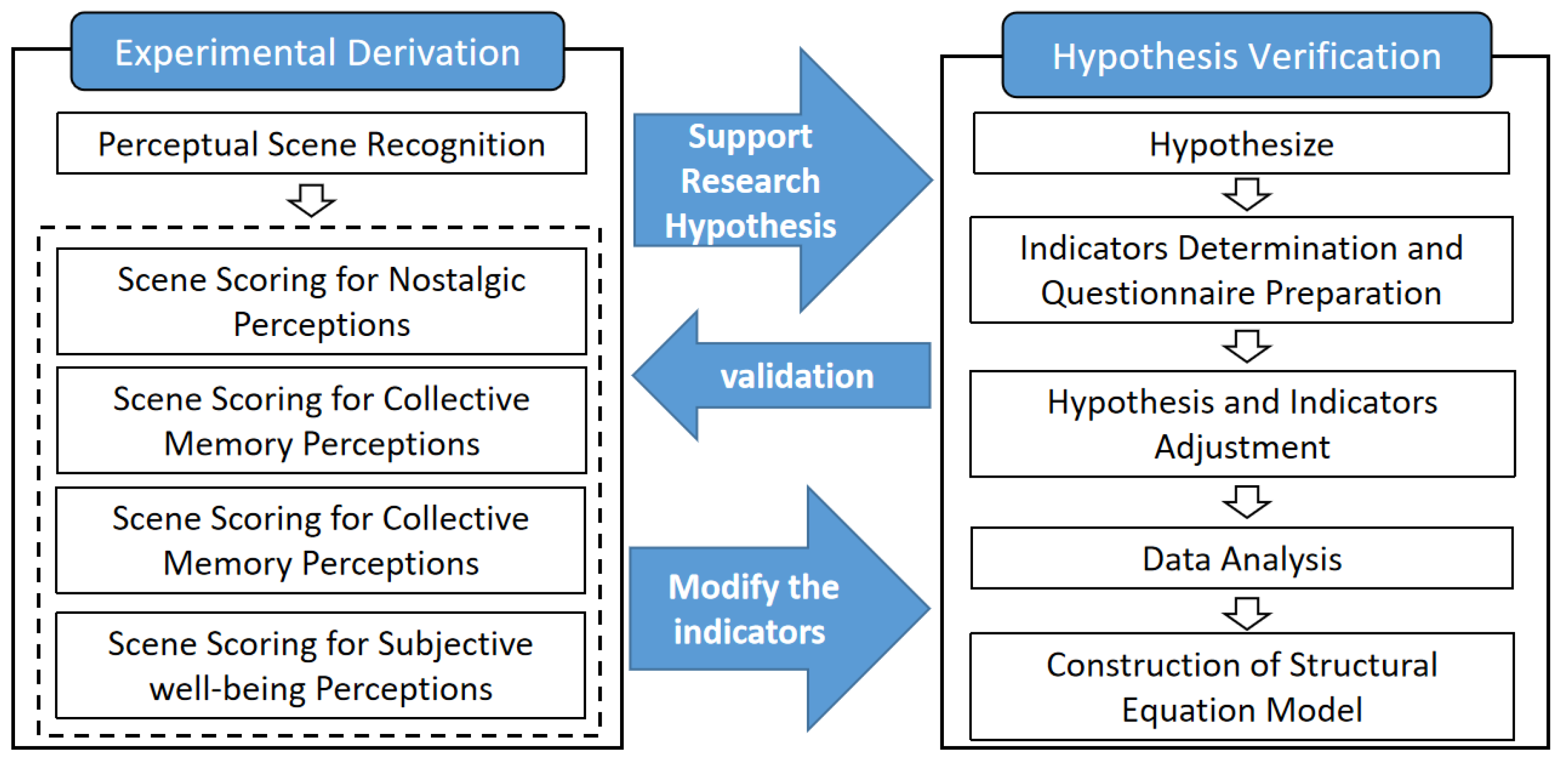

Consequently, this study is conducted through two steps. Firstly, an experimental method involving assigning scores to specific scenes is utilized to validate hypotheses' rationality while gaining initial insights into overall characteristics and spatial distribution of resident's nostalgia, collective memory, subjective well-being and place identity, which sets the foundation for Questionnaire design, hypothesis proposal and structural equation model construction. Secondly based on prior research findings along with experimental survey results questionnaire indicators were structured revised hypotheses proposed leading to construction of a structural equation model (

Figure 2).

3.3. Validation of the Hypothesis Background

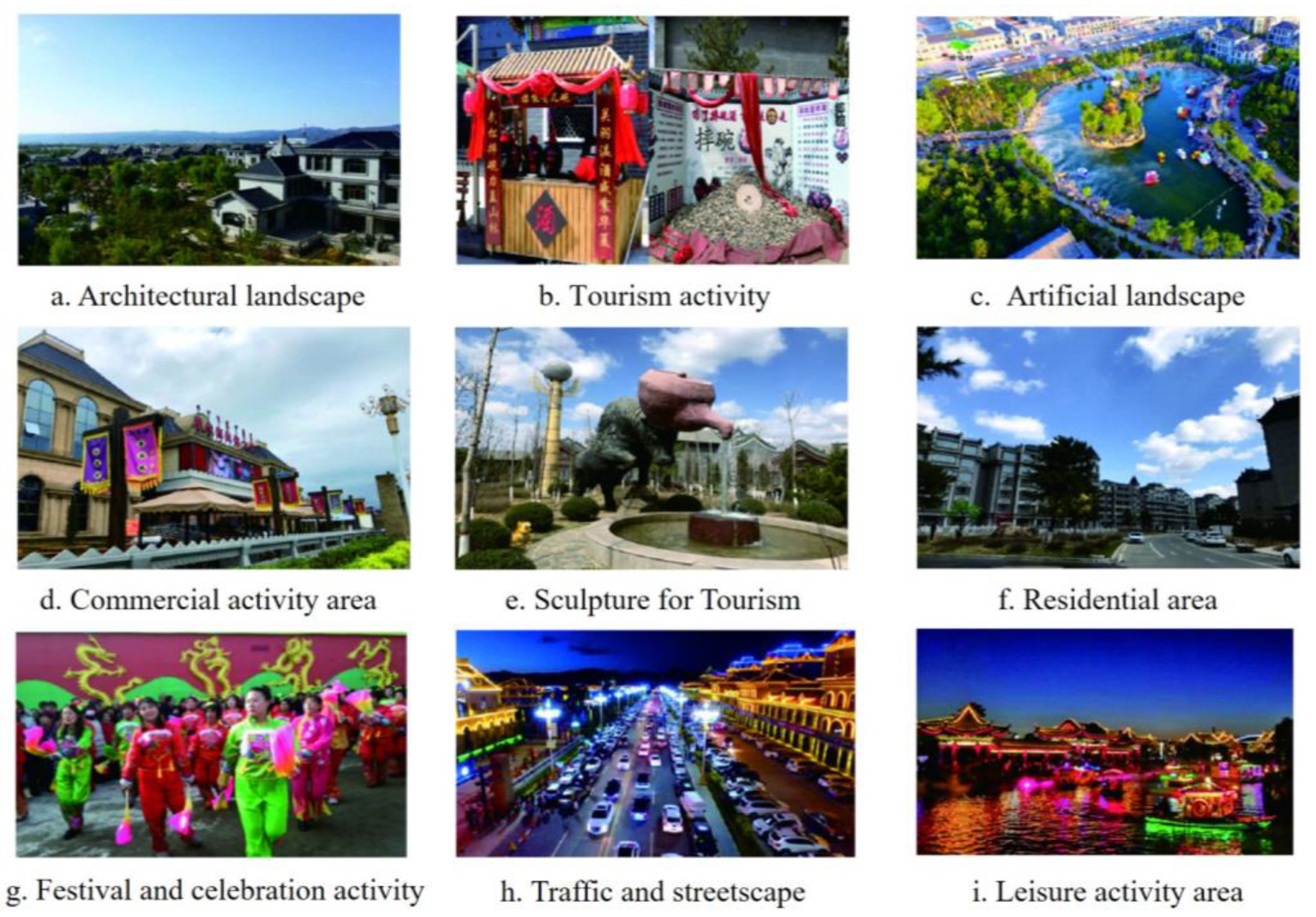

Perceptual scene identification: Relevant images of "Naobao Village" tourism were sought on the authoritative social media platform Weibo, and subsequently subjected to a refinement process. A total of 820 images were preserved and individually coded. These images underwent primary and secondary encoding based on their main subject matter and central theme. Ultimately, nine distinct perceptual scenes were delineated, encompassing architectural landscapes, specialized tourism activity settings, artificial scenic environments, commercial zones, symbolic representations, residential areas, festival venues, transportation thoroughfares, as well as recreational spaces (

Figure 3).

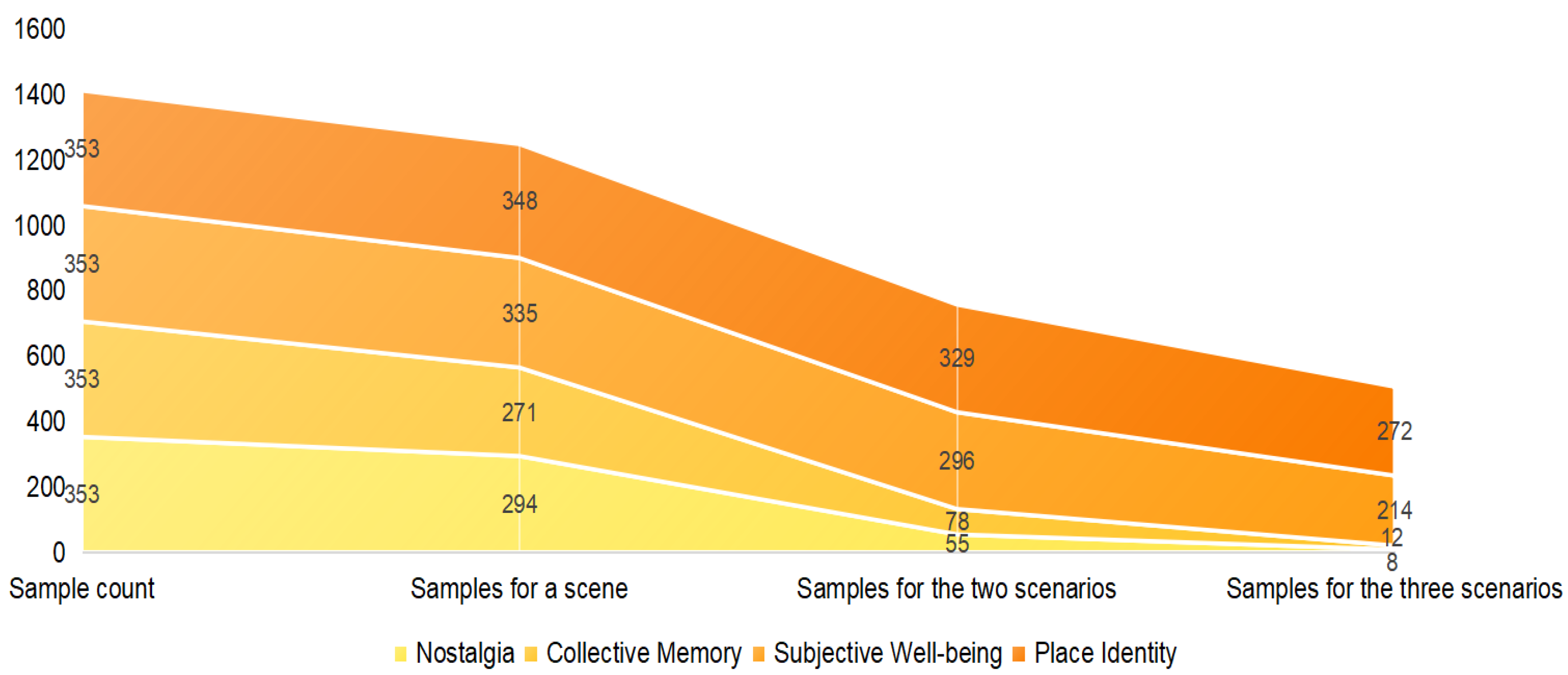

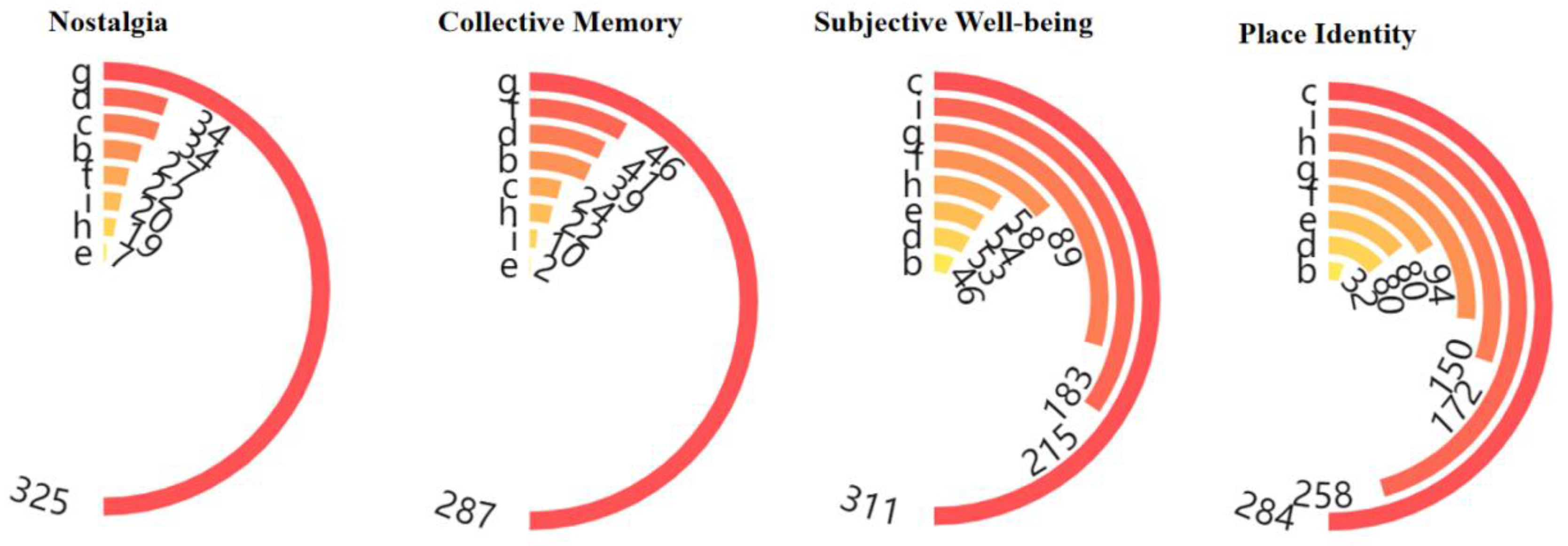

Scene-based rating experiment: Proposed four corresponding topics related to "Nostalgia" "Collective Memory" "Subjective Well-being" and "Place Identity" Each participant was asked to select 1-3 scenes for each question, with one point being awarded for each selected scene. Additionally, the experiment conducted statistical analysis on individual difference variables such as age, gender, ethnicity, monthly income, occupation and length of residence in Brainbao Village. A total of 353 residents from Brainbao Village took part in the scene-based rating experiment.

Results of experiment: 353 participants engaged in the experiment with participation rates of 95.47%, 92.92%, 94.90%, 98.60% across the dimensions of "Nostalgia" "Collective Memory" "Subjective Well-being" and "Place Identity" respectively. The findings indicated that within the dimensions of "Nostalgia" and "Collective Memory", most participants chose only one scene (the festival scene), while over 60% selected three scenes within the dimensions of “Subjective Well-being” and “Place Identity”. It shows that the change of landscape style in the case site has cut off the spatial carrying basis of residents' nostalgia and collective memory and the two emotions of "subjective well-being" and "place identity" are reflected by non-material cultural carriers. In this context, residents exhibited relatively high levels of subjective well-being and place identification which supports our hypothesis regarding how landscape changes stimulate residents' nostalgia, collective memory, subjective well-being and place identy.

In addition, through the statistical analysis of sample individual information, it is found that: Under the background of individual differences such as gender, age, income, education level and living time in Naobao Village, although the sample selection preferences are different, the overall selection trend is relatively concentrated, and the individual differences of different samples will not interfere with the analysis and research of the four psychological and emotional dimensions. This indicates scientific feasibility conducting questionnaire survey these four dimensions Naobao Village.

Figure 4.

Statistics of the number of scene selections from different perspectives.

Figure 4.

Statistics of the number of scene selections from different perspectives.

Figure 5.

Statistics of the types of scene selection from different perspectives.

Figure 5.

Statistics of the types of scene selection from different perspectives.

3.4. Research Methodology and Data Sources

Drawing from the experimental scoring outcomes related to nostalgia, collective memory, place identity, and subjective well-being across 9 scenarios, a survey questionnaire was formulated. The Likert 5-point scale was employed for measurement, with values ranging from 1 to 5 (representing complete disagreement to complete agreement). The first section assesses nostalgia based on the research of Gao et al. (2020)[

58], Batcho (1995) [

59]and Li (2015)[

60]. The second part evaluates collective memory drawing from the works of Stone & Jay (2019)[

61], Qian et al. (2019)[

38], Kong & Zhuang (2017) [

62]among others. The third segment gauges subjective well-being by integrating elements from the classic life satisfaction scale in conjunction with findings from Du et al. (2020)[

29] and Xing (2002)[

63]. Additionally,the fourth part examines place identity derived from studies by Davis(2016)[

64], Zhao & Wu (2017)[

65] and others.The fifth section evaluates tourism effects through economic, social and cultural perspectives while the sixth part focuses on demographic characteristics.

During the period from 2020 to 2023, a total of 5 field surveys, experimental data collection, questionnaire distribution, and supplementary research were conducted in Naobao Village, Huhhot, collecting a total of 353 experimental data. A total of 450 questionnaires were distributed, with 411 effective questionnaires, with an effective rate of 91.11%. And the questionnaire data was analyzed by SPSS 25.0 and AMOS 22 software. First, the reliability and validity of the questionnaire data were analyzed, followed by a normal distribution test. Then, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted, followed by model fitness testing, SEM hypothesis path testing and modification, and finally, based on the SEM path coefficients, the results of the hypothesis test were analyzed.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Validity of Questionnaire Samples

Upon examining the reliability of the 41 indicators in the scale, 1 abnormal item was excluded. The findings indicate that the reliability coefficients (Cronbach's α) for nostalgia, collective memory, subjective well-being, place identity, and tourism effects all exceed 0.7. Additionally, the combined reliability coefficients (CR) for all variables are also greater than 0.7 (see

Table 1), signifying strong data reliability. Factor axis rotation using the maximum variance method revealed factor loadings exceeding 0.5 for each factor. Moreover, with a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of 0.886 (>0.7) and a Bartlett's sphericity test approximate chi-square value of 5532.157 (P=0.000), it is evident that the sample data demonstrates robust structural validity.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

4.2.1. Structural Equation Model Testing

Upon testing the model fitness for the sample using goodness-of-fit indices, the results (

Table 3) indicate that the absolute fit index CMIN/DF is 4.543; GFI is 0.877, AGFI is 0.822; RMR is 0.047. The parsimonious fit index PGFI is 0.697, and the normed fit index NFI is 0.739. Additionally, the relative fit index CFI is 0.919, and the incremental fit index IFI is 0.826.These findings suggest that overall, the model demonstrates acceptable and well-fitted characteristics.

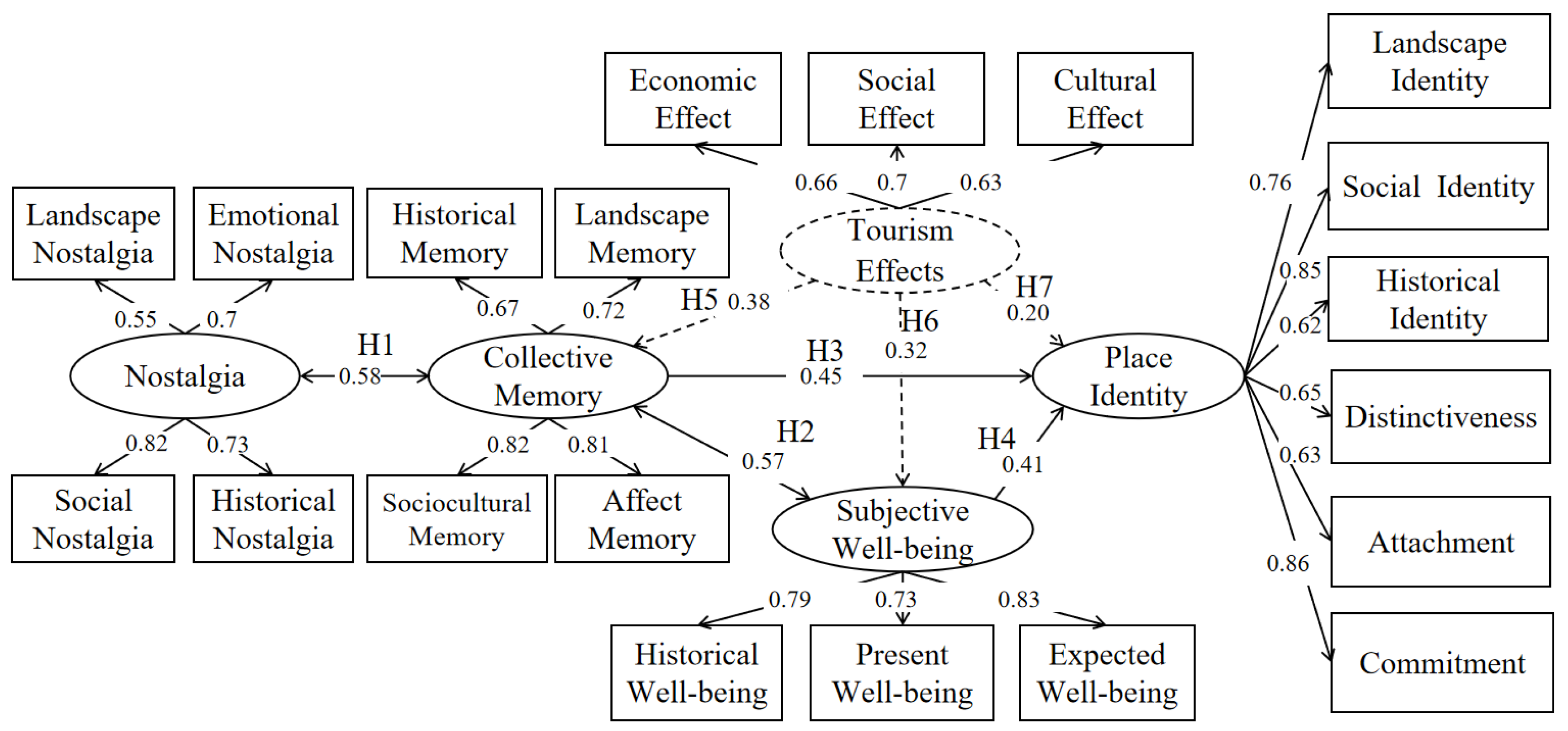

4.2.2. Results of Structural Equation Modeling

First, the study tested H1-H7. In the context of introducing exotic landscapes and generating positive tourism effects, a significant positive correlation was found between nostalgia and collective memory (STD=0.575, P<0.01), H1 is verified. Additionally, there was a notable positive correlation between collective memory and subjective well-being (STD=0.574, P<0.001), H2 is verified. Furthermore, it was observed that collective memory had a substantial positive influence on place identity (STD=0.452,P< 0 .001), H3 is verified. While subjective well-being also exhibited a significant positive impact on place identity (STD = 418 ,P < 0.001), H4 is verified. Tourism effect on collective memory, subjective well-being and place identity have significant positive effects (STD=0.384, P < 0.001, STD=0.201, P < 0.05, STD=0.324, P < 0.001), so H5, H6 and H7 are accepted (

Table 4).

4.2.3. Mediation Effect Test

The mediation effect of the model was tested using the Bias-corrected Percentile Bootstrap method (repeated sampling 5000 times, 95% confidence interval). The indirect effects were through collective memory --> subjective well-being --> place identity (standardized coefficient=0.274), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.197, 0.362]; subjective well-being --> collective memory --> place identity (standardized coefficient=0.315), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.242, 0.370]; tourism effects --> collective memory --> place identity (standardized coefficient=0.309), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.233, 0.359]; tourism effects --> subjective well-being --> place identity (standardized coefficient=0.417), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.346, 0.473]; tourism effects --> collective memory --> subjective well-being --> place identity (standardized coefficient=0.176), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.082, 0.248]; nostalgia --> collective memory --> subjective well-being --> place identity (standardized coefficient=0.058), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.023, 0.078]. All six mediating paths were found to be significant, and all six hypothesized mediating processes were confirmed (

Table 5).

Figure 6.

Model of the Relationship Between Nostalgia, Collective Memory, Place Identity, and Subjective Well-being.

Figure 6.

Model of the Relationship Between Nostalgia, Collective Memory, Place Identity, and Subjective Well-being.

5. Conclusion and Discussion

The article delves into the psychological cognitive mechanisms of inhabitants within the framework of suburban historical and cultural village renewal. A theoretical model outlining the residents' psychological cognitive generation mechanism was developed and validated through experimental and questionnaire methods using structural equation modeling. The results revealed: (1) There is a significant positive correlation between residents' nostalgia and collective memory. Collective memory is positively correlated with subjective well-being, significantly influencing place identity. Subjective well-being among tourists has a notable positive impact on place identity as well. Furthermore, the tourism effects emerge as a pivotal factor affecting residents' perception of their living environment, exerting a significant positive influence on collective memory, subjective well-being and place identity. (2) Both subjective well-being and collective memory play crucial mediating roles; subjective well-being partially mediates the positive impact of collective memory on place identity while collective memory also partially mediates the positive impact of subjective well-being on place identity. Additionally, it was found that collective memory plays a partial mediating role in the positive impact of tourism effects on place identity; meanwhile both collective memory and subjective well-being jointly play a chain mediating role in generating place identification among tourists.

5.1. Discussion

First, This study examines current spatial reconstruction concepts and approaches in suburban rural tourism destinations. Through an analysis of nostalgia, collective memory, place identity, tourism effects and subjective well-being interplay, it validates the initial hypothesis that residents can maintain a strong sense of place identity despite significant changes in their living space and landscape due to a substantial influx of exogenous landscapes[

49]. This observation suggests that the mainstream academic viewpoint, which promotes maintaining the authenticity of rural landscapes and adheres to the principle of "repairing old as before" may not be a one-size-fits-all solution for the spatial reconfiguration of tourist destinations in rural areas[

9,

66]. Consequently, this study introduces new perspectives. The theoretical framework and scientific considerations related to the transformation and reconstruction of suburban rural tourism destinations should encompass a broader range of evaluation dimensions and cognitive viewpoints while integrating them with man-land relationship characteristics at tourist destinations[

5], thereby scientifically formulating novel development pathways for rural tourism destinations[

66]

Second, the research findings elucidate the inherent logical relationships between various measurement dimensions. Firstly, the findings demonstrate a positive correlation between nostalgia and collective memory, which aligns with prior academic perspectives and research outcomes[

11,

13]. Particularly within the specific context of the case study location, this correlation is notably pronounced in relation to tourism effects, indicating that tourism development may act as a catalyst for fostering residents' connections and reflections between past and present[

38]. Additionally, the research establishes a positive correlation between collective memory among residents of the case study area and their subjective well-being, further supporting the constructive role of collective memory in enhancing individual and societal well-being[

16,

17]. Moreover, it confirms a substantial influence of collective memory and subjective well-being on place identity—a finding consistent with Proshansky et al.[

31]. Lastly, the study demonstrates that tourism development not only impacts residents' perceptions of their living environment but also indirectly strengthens their place identity by stimulating collective memory and enhancing subjective well-being[

53,

56]. This underscores that tourism's impact on destinations is multi-dimensional and complex—prompting reconsideration of its influence mechanisms on related concepts from a human geography perspective.

Third, by incorporating the mediating variables of collective memory and subjective well-being, this study has advanced the understanding of the causal relationship between nostalgia, collective memory and place identity. It has also established a theoretical framework for residents' psychological cognition mechanisms. While previous studies have examined the interaction between nostalgic and subjective well-being[

58,

67], as well as the interplay between nostalgia and collective memory[

68], there was a lack of systematic review on the intrinsic logical connection among these concepts possibly due to biased representativeness in different research cases. This study serves as an extension and complement to prior research efforts. It delves into exploring how nostalgia, collective memory, subjective well-being and place identity interact within a distinctive context of rural tourism destination transformation. The study validates strong interactions among these diverse concepts while constructing a theoretical model for understanding the psychological cognition generation mechanism among residents in suburban rural tourism destination transformation[

49,

69]. The aim is not only to elucidate interactive relationships among various emotional characteristics but also to clarify processes and formation mechanisms underlying psychological and emotional changes in suburban historical and cultural villages integrating deductive reasoning principles into social phenomena analysis.

In addition, this study integrated a scene-based rating experiment and questionnaire survey to provide robust support and validation for the structural equation model's pathways, indicators selection and the reliability of these hypotheses. Both research methods have demonstrated that within the context of the renewal of suburban historical and cultural village, there is a positive correlation observed in residents' nostalgia, collective memory, subjective well-being and place identity. The scene-based rating experiment validated the background conditions proposed by the hypotheses and laid a solid foundation for the model. Meanwhile, the questionnaire survey unveiled causal pathways and theoretical models pertaining to residents' psychological cognitive mechanisms. Traditional applications of structural equation models often involve literature review and subjective judgment to formulate research hypotheses subsequent to identifying scientific issues[

70]. Additionally, numerous studies have constructed theoretical frameworks based on grounded theory analysis of textual materials[

71]. However, this study conducted pre-research and verified hypothesis backgrounds using scene-based rating experiment prior to constructing a theoretical framework—thereby strengthening the basis for hypothesis formulation[

72]. Building upon this approach led to revisions in experimental results while determining specific content for the questionnaire survey. Consequently enhancing both rigor and scientific validity in reasoning processes. Furthermore, the results from the questionnaire survey served as additional evidence complementing those obtained from experiments, facilitating an analysis of interactive relationships between concepts through quantitative indicators.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study integrates foundational theoretical concepts from tourism geography, emotional geography, memory behavior, and psychological science to propose a multidimensional theoretical model and analytical framework for investigating the psychological cognitive processes of residents in suburban historical and cultural villages[

4]. This interdisciplinary exploration offers a fresh perspective for comprehending the impact of tourism development on residents' emotional dispositions. Furthermore, it systematically delineates the interplay between nostalgia, collective memory, subjective well-being and place identity within the context of tourism effects. It innovatively synthesizes existing literature on the psychological cognitive mechanisms of residents in tourism destinations[

15,

19,

30], contributing to a novel theoretical framework for future research.

This study conducted a comprehensive analysis of two mediating variables, collective memory and subjective well-being, to elucidate the influence of tourism on residents' place identity through psychological mediation[

30,

53]. Through empirical research, it expands the connotations and operational principles of related concepts such as nostalgia, collective memory and subjective well-being from a tourism perspective, offering new empirical support for the advancement of associated theories[

49]. Additionally, Chen et al. and Nien-Te et al. underscored the multi-dimensional impact of tourism effects on residents' emotional attitudes within economic, social, and cultural contexts[

73,

74]. This discovery holds significant implications for understanding the intrinsic mechanisms of tourism effects and the socio-cultural impacts on spatial reconstruction in rural tourist destinations[

48,

75].

The study has demonstrated an innovative application of methodology. The scientific and comprehensive use of methods has been a prevailing trend in tourism studies for many years[

76]. While the questionnaire survey method and experimental method have been widely employed in social sciences, psychology, and other disciplines focusing on cognitive behavior[

77], their specific combined applications vary due to differences in research objectives and subjects. This study creatively integrates scene-based rating experiment with structural equation model research, establishing a robust empirical foundation for constructing structural equation models and interpreting scene-based rating experiment results. This enhances the scholarly rigor of the study while introducing novel ideas for methodological applications in future research.

5.3. Practical Contributions

The research can offer insights for the development planning and practical implementation of rural tourism landscape reconstruction in suburban historical and cultural villages. It verifies the objective reality that local residents in suburban historical and cultural villages still strongly identify with the reconstructed tourism landscape within the context of renewal. This suggests the necessity to preserve and develop local cultural characteristics, as well as to innovatively integrate culturally distinctive and appealing landscape elements during the process of updating the planning and reconstruction of suburban historical and cultural villages and rural tourism landscapes[

78]. The integration of diverse landscape cultures is essential for promoting the preservation, development and innovation of rural landscape culture during destination development, planning and reconstruction.

The study offers an evaluative perspective from the standpoint of residents in suburban historical and cultural villages to validate the quality of tourism destination development. Residents are key stakeholders in rural tourism destinations and serve as significant attractions for tourists. The study examines the psychological cognitive processes experienced by residents in rural tourism areas when confronted with reconstructing their landscapes within a context influenced by tourism effects. This analysis holds important implications for better reconciling contradictions between tourism development and community progress, ultimately enhancing the well-being of residents.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has certain limitations that should be addressed in future research. Firstly, the selection of specific case areas and research perspectives to validate the initial research hypotheses may not fully capture the diversity of situations across other suburban rural tourism destinations. Future studies could employ a multi-case comparative approach to enhance the generalizability of findings. Secondly, regarding research methodology, while the scene-based rating experiment focused solely on residents' visual perception, incorporating embodied theory for a comprehensive assessment of residents' emotional inclinations may offer a more systematic and precise understanding. Additionally, there is potential for further integration of experimental methods and questionnaire surveys in future research to establish a more standardized research paradigm. Furthermore, it's worth noting that the academic concepts utilized in explaining residents' psychological cognitive mechanisms were primarily derived from relevant literature studies and subjective analyses of objective phenomena. However, there may be additional critical factors influencing this mechanism yet to be uncovered, representing an avenue for future in-depth exploration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M. L., C. T., and L. Z.; Methodology, M. L. J. W. and T. W.; Investigation, M. L. and R. Y.; Writing - original draft, M. L., T. W., L. Z. and C. T.; Writing - review & editing, M. L., L. Z., J.W. and R. Y.; Resources, T. W.; Supervision, L. Z. and C. T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by National Social Science Foundation of China (20BMZ131), Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia (2019MS04019).

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from Meng Li on reasonable request, and his email address is limeng202@mails.ucas.ac.cn.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Part I: Place a "√" on the option for the level of consent you approve, depending on how you feel. (1 = very disagree, 5 = very agree, the higher the score, the more you agree).

| Nostalgia |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| I miss the natural scenery and natural landscape of the former Naobao village |

|

|

|

|

|

| I miss the buildings, the courtyards, the streets and so on of the old village |

|

|

|

|

|

| I can recall my former relatives and friends in the village of Naobao |

|

|

|

|

|

| Being in the village of Naobao can remind me of happy or sad things in my past |

|

|

|

|

|

| I miss the neighbors I used to have |

|

|

|

|

|

| I miss the lively atmosphere when friends and family gathered together |

|

|

|

|

|

| I miss where I used to live |

|

|

|

|

|

| I miss the way I used to live |

|

|

|

|

|

| Place identification |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| I think the natural environment and climatic conditions of Naobao Village are suitable for living |

|

|

|

|

|

| I think the landscape of the village is very beautiful. I like the present landscape very much |

|

|

|

|

|

| I think the life in Naobao village is very convenient, all kinds of living facilities are very perfect |

|

|

|

|

|

| I think the residents of Naobao Village are very warm and friendly, and the social order is very good |

|

|

|

|

|

| I think Naobao village has better protected the local regional culture |

|

|

|

|

|

| In my opinion, Naobao Village has better preserved and inherited the local landscape style |

|

|

|

|

|

| I think the folk activities and festivals in Naobao Village can reflect the local traditional culture |

|

|

|

|

|

| I feel that I am a part of the Naobao Village, and I will be proud to be a Naobao Village resident |

|

|

|

|

|

| I think Naobao Village has many advantages that other villages do not have |

|

|

|

|

|

| Living in Naobao village gave me a strong sense of belonging |

|

|

|

|

|

| The village of Naobao and its people are of great significance to me |

|

|

|

|

|

| I think the future development of Naobao village is closely related to me |

|

|

|

|

|

| I would like to contribute to the future development of the village |

|

|

|

|

|

| I very much agree with the current Naobao village |

|

|

|

|

|

| Collective memory |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| I was able to point out exactly where the village of Naobao used to be |

|

|

|

|

|

| I know very well the local character of the village of Naobao in the past |

|

|

|

|

|

| I remember very well the former natural scenery and scenery of the village of Naobao |

|

|

|

|

|

| I remember very well the old buildings, the courtyards, the streets, etc |

|

|

|

|

|

| I remember very well the intercourse between the old neighbors of the village of Naobao |

|

|

|

|

|

| I remember very well the festivals, performances, customs and so on in the past |

|

|

|

|

|

| I remember very clearly the life that my family and I lived in the village of Naobao |

|

|

|

|

|

| I remember very well the happy and sad things that I used to experience in the village of Naobao |

|

|

|

|

|

| I miss my past village very much, often with the feeling of not giving up |

|

|

|

|

|

| I have a deep memory of the village of Naobao in the past |

|

|

|

|

|

| Subjective Well-being |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| If I could live my life over again, I would change almost nothing |

|

|

|

|

|

| The living conditions I have been living in Naobao Village have been very good |

|

|

|

|

|

| I'm happy with my life right now |

|

|

|

|

|

| I've got the most important thing I ever wanted in life |

|

|

|

|

|

| My life in Naobao village is close to my ideal life in the future |

|

|

|

|

|

| I believe I will live a happier life in Naobao Village |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tourism effects

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Tourism development has promoted the economic development of Naobao village |

|

|

|

|

|

| The development of tourism has promoted the social development of Naobao village |

|

|

|

|

|

| The development of tourism has promoted the cultural development of Naobao village |

|

|

|

|

|

Part II: Personal basic information

1. Your age: _____; Your gender: ① male ② female; Your nationality is ________;

Are you living in Naobao Village now?

① Yes ② No; Did you grow up in the village of Libao? ① Yes ② No;

You have lived in the village:

① less than 1 year ②1-5 years ③6-10 years ④11-15 years ⑤ more than 15 years.

2. Your education level: ① junior high school and below ② high school and secondary school ③ junior college and undergraduate ④ postgraduate

Your average monthly income (Yuan) : ①≤2000 ②2001-3000 ③3001-5000 ④>5000

4. Your occupation: ① civil servant ② enterprise staff ③ professional/cultural and educational technical personnel ④ service sales business personnel

⑤ Workers ⑥ farmers ⑦ soldiers ⑧ students ⑨ retirees _______

References

- Maziliauske, E. Innovation for sustainability through co-creation by SMEs: Socio-cultural sustainability benefits to rural destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 50, 101201. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Y.; Xie, J.; Xu, X.Y. Facilitating "migrant-local" tacit knowledge transfer in rural tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2024, 100, 104836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Wen, R.Y.; Zeng, Y.Y.; Ye, K.; Khotphat, T. Seasonality's impact on rural tourism livelihood sustainability. Sustain. 2022, 14, 10572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ismail, M.A.; Aminuddin, A. Rural tourism's influence on traditional village sustainable development. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25627. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, X.T.; Huang, Z.F.; Zhang, H.M.; Pan, R.; Jin, J. Rural tourism destination rurality changes in China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 04. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.K.; Wu, T.H.; Tang, W.Y. Tourism virtual community member participation and behavior. Resour. Sci 2019, 1734–1746. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Olczak, B.; Wilkosz-Mamcarczyk, M.; Prus, B. , et al. Building cohesion method in suburban historical landscape planning. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biłozor, A.; Czyż, S.; Bajerowski, T. Transitional zone identification between urban and rural areas. Sustain. 2019, 11, 7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomopoulou, E.; Delegou, E.T.; Sayas, J.; Vythoulka, A.; Moropoulou, A. Cultural landscape preservation for rural development. Land 2023, 12, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.L. "Preserving nostalgia" in new urbanization construction. Geogr. Res. 2015, 34, 1205–1212. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Lasaleta, J.D.; Sedikides, C.; Vohs, K.D. Nostalgia weakens the desire for money. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. Past time, present place: landscape and memory. Geogr. Rev. 1975, 65, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.P.; Gorman-Murray, A. Nostalgia in black and white: photography and the geographies of memory. Aust. Geogr. 2023, 54, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.G.; Chen, T.; Lin, M.S.; Wang, S.K. Progress and enlightenment of domestic and foreign research on nostalgia. Hum. Geogr 2018, 1–11. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Qian, L.L.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, C.H.; Liu, P.X.; Zhang, J.R.; Zhang, H.L. A review of studies on collective memory from the perspective of geography. Hum. Geogr 2015, 7–12. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, M. On Collective Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Zhao, Y.; Fan, J.H. The presentation and construction of collective memory in nostalgic films. Contemp. Cinema 2019, 112–115. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Blunt, A. Collective memory and productive nostalgia: Anglo-Indian homemaking at McCluskieganj. Environ. Plan. D: Soc. Space 2003, 21, 717–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, O.; Tavani, J.L.; Collange, J. A preliminary experimental test of the crossed influences between the valence of collective memory and collective future thinking. Memory 2024, 32, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, P. Evoking nostalgia: graffiti as medium in urban space. Sage Open 2023, 13, 21582440231216600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yang, J.B.; Huang, W. The evolution of urban nostalgic spaces and the construction of multiple subjects: A case study of Tongji Bridge in Foshan City. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 30, 29–37. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Busseri, M.A. Evaluating the structure of subjective well-being: Evidence from three large-scale, long-term, national longitudinal studies. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2024. Early Access.

- Shin, D.C.; Johnson, D.M. Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 1978, 5, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Diener, M.; Diener, C. Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 851–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawa, N.E.; Yamagishi, N. Distinct associations between gratitude, self-esteem, and optimism with subjective and psychological well-being among Japanese individuals. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and emotion. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heady, F.; Wearing, A. Personality life events and subjective well-being: Toward a dynamic equilibrium model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G.Q.; Cai, R.; Li, Y. Factors influencing residents' subjective well-being at world heritage sites. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Lyu, H.C.; Li, X.B. Social class and subjective well-being in Chinese adults: The mediating role of present fatalistic time perspective. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 41, 5412–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Yan, X.; Jie, C.W.; Zhou, P.Y. The chain mechanism of subjective happiness of red tourists. Arid Zone Resour. Environ 2023, 178–185. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.K. Terrae incognitae: The place of imagination in geography. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1947, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.J.; Liu, A.L. Research progress on the connotation dimensions and influencing factors of place identity. Prog. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 38, 662–674. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Marschall, S. Tourism and memory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 2216–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.L.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, C.H.; Zhang, H.L.; Guo, Y.R.; Yan, B.J. Space reconstruction of the old town of Beichuan after the earthquake based on collective memory. Hum. Geogr. 2018, 53–61. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Fortier, A.M. Re-membering places and the performance of belonging(s). Theory Cult. Soc. 1999, 16, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, C.W. Landscape, memory, history: Gloomy memories and the 19th century Scottish highlands. Scott. Geogr. J. 2005, 121, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.L.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, C.H.; Guo, Y.R. The relationships among post-disaster collective memory, place identity, and place protection intention of local residents: A case study of Wenchuan earthquake ruined town of Beichuan. Geogr. Res 2019, 988–1002. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.F.; Nie, X.Y. The mechanism of collective memory in cultural tourism destinations affecting tourists' place attachment: A case study of Wuzhen, Pingyao Ancient City, and Fenghuang Ancient City. Areal Res. Dev. 2018, 37, 95–100. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Korpela, K.M. Place-identity as a product of environmental self-regulation. J. Environ. Psychol. 1989, 9, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricchiolo, F.; Mosca, O.; Paolini, D.; Fornara, F. The Mediating Role of Place Attachment Dimensions in the Relationship Between Local Social Identity and Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 645648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodori, G.L. Examining the effects of community satisfaction and attachment on individual well-being. Rural Sociol. 2001, 66, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, I.; Eliasson, I. Relationships between Personal and Collective Place Identity and Well-Being in Mountain Communities. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Bai, K. Place attachment and happiness of Xi'an Huifang tourism labor migrants. Tourism Tribune 2017, 32, 12–27. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Vada, S.; Prentice, C.; Hsiao, A. The influence of tourism experience and well-being on place attachment. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A. Size and type of places, geographical region, satisfaction with life, age, sex and place attachment. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 47, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, M.M.; Xiao, H.G. Construction of collective memory and national identity through homeland visits: Narratives from Chinese immigrants. Tourism Tribune 2022, 37, 46–61. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ankholmes, A.; Mckercher, B. Rethinking slavery heritage tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2015, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, T.H.; Zhong, L.S. Characteristics and interactive relationships of nostalgia, collective memory, and place identity among residents of internet-famous "Red Tourism Villages": A case study of Naobao Village, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2022, 42, 1799–1806. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Layard, R. The case for psychological treatment centres. Br. Med. J. 2006, 332, 1030–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagerty, M.R.; Cummins, R.A.; Ferriss, A.L.; Land, K.; Michalos, A.C.; Peterson, M.; Sharpe, A.; Sirgy, M.J.; Vogel, J. Quality of Life Indexes for National Policy: Review and Agenda for Research. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001, 55, 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupinski, J. Health and Quality of Life. Soc. Sci. Med. 1980, 14(3A), 203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Tajeddini, K.; Altinay, L. Experiential Festival Attributes, Perceived Value, Cultural Exploration, and Behavioral Intentions to Visit a Food Festival. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2023, 24, 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.; Johnson, S. The Happiness Factor in Tourism: Subjective Well-Being and Social Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 41, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, M.J. Interactional Past and Potential: The Social Construction of Place Attachment. Symb. Interact. 1998, 21, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Sun, Q. The Superposition of Place Meaning and Place Identity of Qiaoxiang in the Context of Tourism Development: A Case Study of Wulin, Jinjiang, Quanzhou. Trop. Geogr. 2022, 42, 29–42. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.Y.; Zhang, Z.S.; Niu, S.Y. Amnesia and Reconstruction of Collective Memory of Intangible Cultural Heritage in the South China Sea "Genglu Book". Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 2281–2294. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Lin, S.T.; Zhang, C.Z. Authenticity, Involvement, and Nostalgia: Understanding Visitor Satisfaction with an Adaptive Reuse Heritage Site in Urban China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batcho, K.I. Nostalgia: A Psychological Perspective. Percept. Mot. Skills 1995, 80, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Theorizing “Nostalgia” and Its Implications on Cultural Heritage Preservation of Rural and Urban China. J. Beijing Union Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2015, 13, 51–57. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Stone, C.B.; Jay, A.C.V. From the Individual to the Collective: The Emergence of a Psychological Approach to Collective Memory. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2019, 33, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Zhuo, F.Y. Roles of Cultural Landscapes in the Construction of Local Collective Memory: A Case Study of Chengkan Village. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2017, 37, 110–117. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Z.J. A Review of Research on the Measurement of Subjective Well-Being. Psychol. Sci 2002, 336-338+342. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A. Experiential Places or Places of Experience? Place Identity and Place Attachment as Mechanisms for Creating Festival Environment. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.J.; Wu, B.H. A Study on the Place Identity Model Based on Leisure Temporal-Spatial Involvement. Tourism Tribune 2017, 32, 95–106. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, C.A.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Adamov, T.; Ciolac, R. The Impact of Agritourism Activity on the Rural Environment: Findings from an Authentic Agritourist Area - Bukovina, Romania. Sustain. 2023, 15, 10294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, D.; Ramkissoon, H. Nostalgic Emotions, Meaning in Life, Subjective Well-Being and Revisit Intentions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 48, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungselius, B.; Weilenmann, A. Keeping Memories Alive: A Decennial Study of Social Media Reminiscing, Memories, and Nostalgia. Soc. Media Soc. 2023, 9, 20563051231207850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.M.; Qu, Y.; Yang, Q. The Formation Process of Tourist Attachment to a Destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Chowdhury, M.; Prajogo, D.; Mariani, M.; Guizzardi, A. Residents' Perceptions of Environmental Certification, Environmental Impacts and Support for the World Expo 2015: The Moderating Effect of Place Attachment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 34, 1204–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiras, A.; Eusébio, C. Perceived Image of Accessible Tourism Destinations: A Data Mining Analysis of Google Maps Reviews. Curr. Issues Tour 2023, 07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Koo, C.; Yang, S.B. Spatial and Social Distances Between US Domestic Travelers in Restaurant Review Assessment. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lehto, X.Y.; Cai, L.P. Vacation and Well-Being: A Study of Chinese Tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 284–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nien-Te, K.; Cheng, Y.S.; Chang, K.C.; Hu, S.M. How Social Capital Affects Support Intention: The Mediating Role of Place Identity. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, C.J.; Liu, Z.W.; Yang, L.S.; Wang, L. Evaluation of Spatial Reconstruction and Driving Factors of Tourism-Based Countryside. Land 2022, 11, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Cortes, G. Research on Literacy in Tourism: A Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2024, 34, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.Y.; Hsu, Y.S.; Chen, H.S. Choice Experiment Method for Sustainable Tourism in Theme Parks. Sustain. 2021, 13, 7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmafitria, F.; Pearce, P.L.; Oktadiana, H.; Putro, H.P.H. Tourism Planning and Planning Theory: Historical Roots and Contemporary Alignment. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 35, 100703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).