1. Introduction

One of the most significant and imminent threats to humanity's continued existence is climate change. It is imperative that significant contributions are made to the mitigation of universal threats if future development is to be sustainable. However, education, and particularly university education, seldom incorporates global perspectives or addresses complex transdisciplinary and general issues. Moreover, science is still largely regarded as the domain of experts educated at universities by specialists engaged in narrowly focused research.

As a first step towards the integration of global as well as transdisciplinary aspects into university education, the authors have developed a curriculum for a Master’s programme taught by academics from three branches of sciences—legal, natural, and social sciences—within the framework of a technical university that focuses on computer science. The main argument for why this curriculum should be institutionalised at a technical university is that technical studies are strongly linked with industry. In the contemporary era, the industry is increasingly inclined to present sustainability reports in order to document progress. Consequently, the fundamental assumption is that industry, as a significant stakeholder, particularly at technical universities, is the principal actor with an interest in sustainability. Therefore, it is assumed that the industry will support and foster efforts to establish a curriculum that addresses global risks and climate change. Furthermore, it is assumed that global risks cannot be controlled financially. Consequently, the industry will have to make a greater effort to manage these issues, which is where sustainability comes into play.

The core ideas behind this curriculum, its content, and the strategies for its implementation are explained in this article. In the absence of a universally accepted definition of the terms "climate change" and "global risk", this paper begins by defining and delineating the concepts that will be used throughout the text. At this juncture, the term "climate change" is employed to encompass both anthropogenic and natural risks. Global risks encompass both human-induced and naturally occurring threats and are characterised by high levels of interconnectedness. Moreover, the primary hypothesis of this study is that sustainability as an overarching objective necessitates a global perspective, as well as transdisciplinary education and research.

Transdisciplinarity here, according to its Latin etymology, means beyond disciplinarity. In consequence, it represents a research and teaching strategy that transcends the boundaries of numerous disciplines, thereby facilitating a holistic approach. Transdisciplinarity applies to research and teaching efforts focused on grand questions that cross the boundaries of multiple disciplines, such as climate change. Transdisciplinarity pertains to theories, concepts, and methodologies that were initially developed by one discipline but are now applied by various others; i.e., expert interviews, a qualitative empirical research method first developed in sociology but now frequently used by other disciplines. Regarding the content of the article, the term here specifically refers to a systematic scientific way of addressing climate change as the most pressing global risk facing humanity via a holistic approach and, by doing so, creating comprehensive knowledge beyond disciplines.

The envisioned Master’s programme should be taught by lecturers from three branches of sciences—legal, natural, and social sciences—in the framework of a technical university with a focus on computer science. The main argument for the given attention to computer science is evident: digital tools play a part in all mentioned branches of sciences. As such, new digital technologies are seen here as a key tool and as a cross-cutting topic in the context of the curriculum. Furthermore, various reports demonstrate the nexus between digitalisation, artificial intelligence, and global risks such as climate change. In this sense, the underlying idea of the curriculum is to provide a continuous and sustainable interlinking of legal, natural, and social scientific areas of knowledge with new digital technologies as a cross-cutting issue.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Global Landscape

Exponential population growth had led to approximately 2.5 billion people by the 1950s [

1] (p. 251), when the first warnings of global limits to growth were published by the physicist Charles Galton Darwin [

2] in 1953, the grandson of Charles Darwin. A more detailed discussion of the need to consider these limits was published just one year later by the chemist Harrison Brown [

3] in 1954. A major part of his book "The Challenge of Man's Future" is already devoted to the limited fossil fuel resources and the eventual need to "turn to the sun for the fulfilment of our energy requirements" [

3] (p. 182).

2.1.1. From Disasters to Global Existential Risks

Disasters are defined by the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC) as "serious disruptions to the functioning of a community that exceed its capacity to cope using its own resources" [

4]. Disasters can be natural or manmade. Global catastrophic risks are "hypothetical events" [

5] (p. 1), whereby global existential risks, as defined by Bostrom [

6] (p. 3), are the most catastrophic "where an adverse outcome would either annihilate Earth-originating intelligent life or permanently and drastically curtail its potential."

Throughout the history of the planet, several natural mass extinctions have reduced biodiversity, often due to natural climate change caused by variations in the Earth's orbit around the Sun. The most recent mass extinctions, between 450 and 60 million years ago, each killed more than 70% of all species living at the time [

7] (2011, p. 52). In most cases, climate change likely played a major role.

While natural disasters have occurred many times in human history, anthropogenic (man-made) global catastrophic or even existential risks began with the detonation of the first atomic bomb in 1945. According to an interview published in The American Weekly of 8 March 1959 by Pearl S. Buck with 1927 Nobel Prize winner Arthur Holly Compton, Chancellor of Washington University and former director of the Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb, in 1943, the leading scientists of the project could not rule out with certainty the possibility that the ignition of the nuclear fission reaction might lead to temperatures high enough to initiate the nuclear fusion of hydrogen (in the oceans) or nitrogen (in the atmosphere) and thus "vaporise the Earth". He quotes Compton as saying that if there was a three-in-a million chance that the Earth would be vaporised by the nuclear explosion, he would not have gone ahead with the project. The calculations revealed that the numbers were slightly lower, and the project continued [

8], leading to the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. In the same year, a number of scientists, including Albert Einstein and several who had developed the atomic bomb, founded a non-profit organisation and a journal called the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists of Chicago to inform the public about the threat of nuclear weapons. In 1947, it first displayed the iconic Doomsday Clock, set at eight minutes to midnight, symbolising the urgent need for action. Although initially focused solely on the spectre of nuclear annihilation, Eugene Rabinowitsch, the Bulletin's founding co-editor, warned that the atomic bomb would be "only the first of many dangerous presents from the Pandora’s Box of modern science" [

9] (p. 14).

The Bulletin's Doomsday Clock is a vivid symbol of global threats. Starting at eight minutes to midnight in 1947, it was moved to three and then two minutes to midnight when the Soviet Union tested its atomic bomb in 1949, and the US tested its first hydrogen (fusion) bomb in 1952. Global détente led to the handles being moved back to 12 minutes to midnight in 1963, following the signing of the Test Ban Treaty. In 1991, at 17 minutes to midnight, the hand reached its greatest distance from midnight after the end of the Cold War. Since then, hands have been moving closer to midnight, and since 2007, they have been driven ever faster by the growing risk of catastrophic climate change. In 2023, the time remaining until the designated point of no return was 90 seconds, representing the shortest interval ever recorded between such a juncture and the potential for global catastrophe. [

10].

The World Economic Forum (WEF), which was founded in 1971 to "demonstrate entrepreneurship in the global public interest" by developing "stakeholder responsibility" at the global level via a systemic (holistic) approach, began publishing Global Risks Reports in 2006 to summarise its efforts to assess and prioritise global risks [

11]. Starting with a list of six economic, six societal, four environmental, four technological, and three geopolitical risks, the Global Risks Report 2023 lists, discusses, and ranks 32 global risks [

11]. A "global risk" is "the possibility of the occurrence of an event or condition that, if it occurs, could cause significant negative impact for several countries or industries" [

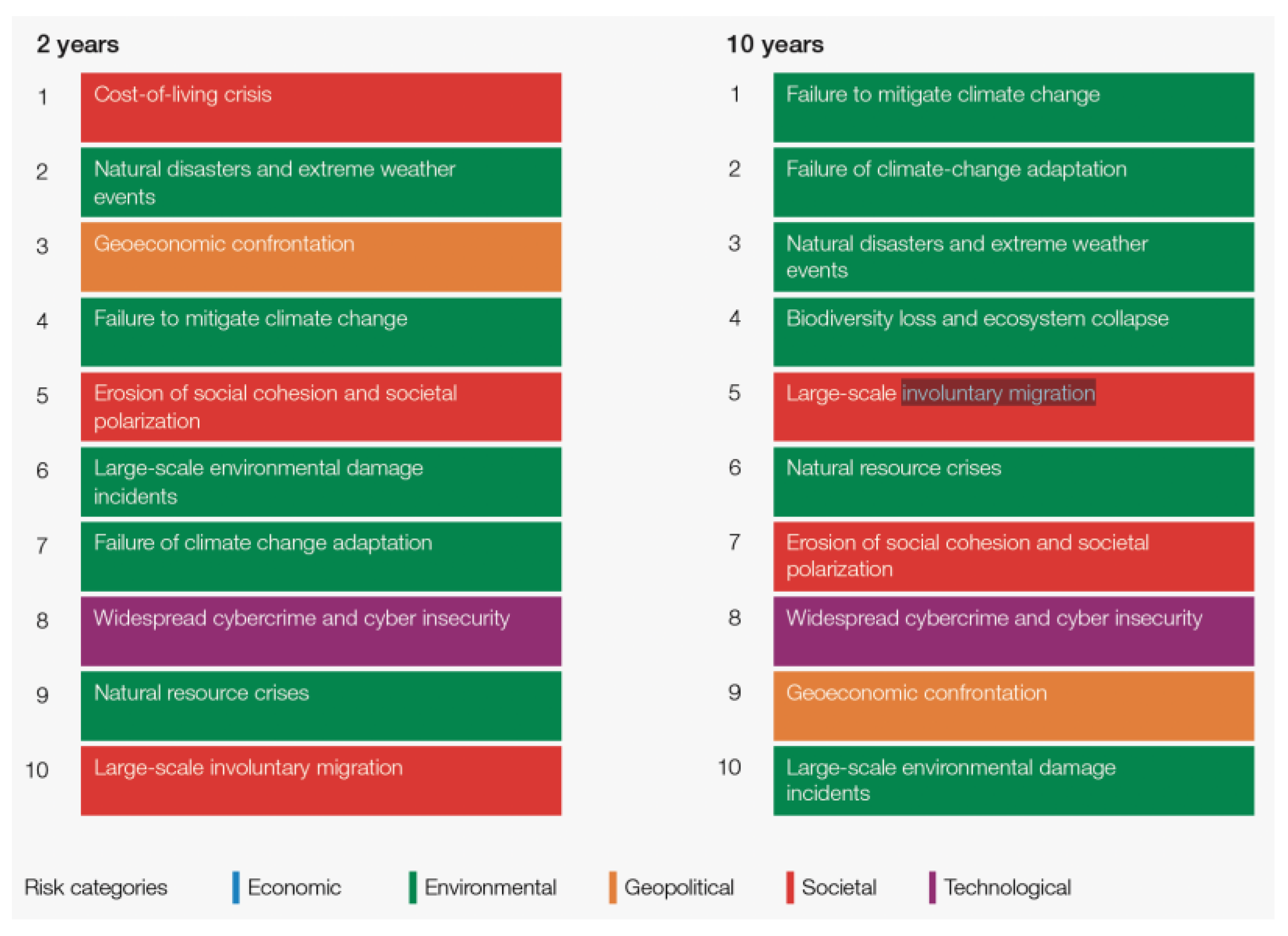

12]. Ranking the long-term (over the next 10 years) global risks by severity, three climate-related risks (failure to mitigate climate change, failure to adapt to climate change, and natural disasters and extreme weather events) are identified. Of the top 10 risks, six are environmental, with biodiversity loss in the top four after the three climate change risks, natural resource crises in sixth place, and major environmental incidents in tenth place (see

Figure 1). To quantify the different environmental risks to the stability of the Earth system, the Stockholm Resilience Centre, which was headed by Johan Rockström, developed the planetary boundaries concept [

13]. The latest update was published in 2015 by a large group of scientists [

14] but was further developed by several research groups [

15].

Most of the discussions on global threats have originated from the "hard" (natural) sciences. Early studies in "soft" sciences, mainly in sociology, are summarised in a paper by Centeno et al. [

16]. In a new article, Rockström et al. [

17] proposed integrating safety and justice criteria into the Earth system boundaries (ESBs) and identified hot spots of current ESB transgressions.

2.2. Understanding Global Complexity

2.2.1. Global Studies: A Transdisciplinary Endeavour

In general, Global Studies emerged as transdisciplinary endeavours exploring the many dimensions of globalisation in the late 1990s. Scholars working within the Global Studies framework employ transdisciplinarity strategies to understand global complexity [

18]. In this respect, Global Studies is more than the study of globalisation; at its core, it is driven by the search for global perspectives and aims to conceive approaches for transdisciplinary innovation and open-ended exploration.

Global Studies scholars discuss global contexts in transdisciplinary discourses, focussing on the overall framework of global contexts and issues. They take a holistic approach to science and education, transcending traditional disciplinary boundaries and recognising Aristotle's principle [

19]: "The whole is greater than the sum of its parts". Global Studies does not see itself as a complement to various disciplines, but the original disciplines themselves no longer play a role.

Although Global Studies has thus far succeeded in enabling a universal perspective in science and education and in enriching transdisciplinary discourses, it still lacks a connection to the legal and natural sciences. Starting from the central assumption that climate change is an issue that has been predominantly worked on and driven by natural scientists but that needs to be analysed from a global perspective and in a transdisciplinary way, the link between global risks and social sciences is evident.

2.2.2. The Nexus of Global Risks and Social Sciences

Global risks are universal issues that can be fully understood only in a transdisciplinary way and are therefore linked to the social sciences. This interface is illustrated by two aspects: first, the discussion of global models of society, and second, the elaboration of world political issues.

First, outside the narrow understanding of the equation of state and society, scholars have focused on social models in a global context. These include approaches of international society [20, 21, 22], which are derived from international relations scholars; transnational society [

23], which is discussed by political scientists; and global society [

24], and world society [25, 26, 27, 28, 29], which are rooted in sociological and sociopsychological discourses. Despite the differences in their theoretical foundations and methods, all of the aforementioned models of society concur that any comprehensive understanding of society must be contextualised within a global framework. In this context, any state-based understanding of society that equates society exclusively with the state is no longer a sufficient or appropriate means of understanding social and societal structures and relationships in the present era. A similar argument can be made with respect to climate change. It is not feasible to conduct a comprehensive analysis of this phenomenon within the confines of national or world-regional boundaries. It is therefore evident that there is considerable merit in pursuing a linkage between social models in a global context and climate change, both in the context of future research and teaching agendas.

The international community is increasingly aware that the greatest universal threats to humanity derive from common environmental risks. In recent decades, the proliferation of scientific knowledge about climate change (see, e.g., [30, 31, 32, 33, 34]), and planetary boundaries (see, e.g., [35, 36]), along with public awareness of ecological devastation, have been core drivers in shaping the discourse of climate-related science. Climate-related issues can only be fully understood from a global perspective. At this point, scholars debating global models of society can contribute insights into existing discourses on climate change. The concepts of world society offer promising avenues for joint research between social scientists and climate scientists. The link between environmental issues and the concepts of world society can be outlined through future scenarios of research collaboration [

37].

Second, matters of global governance [38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43] and multilateral cooperation are debated in political sciences and international relations. Global processes are changing the role of states, and climate change is reshaping issues of political power. Environmental risks challenge conventional forms of political power. No state in the world is unaffected by climate change, and no political regime can govern it alone. Climate change is bringing the state back into the stage of global political order. At the same time, it is clear that states must work together to find an effective and sustainable way of addressing this global risk. The steady growth of civil society organisations since the 1990s has also remained a global political trend. Just as civil society organisations have become active actors in addressing universal environmental issues, they have also become relevant actors in global politics. Civil society organisations around the world are playing the role of 'watchdogs' in the implementation of environmental multilateral treaties by governments, i.e., the implementation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (Paris Agreement) or the Sustainable Development Goals proclaimed by the UN [

45] and are perceived as relevant actors in world politics. With respect to civil society and the universal risk of climate change, people around the world are forming transnational political spaces and thus reshaping world politics. In view of the global risks posed by climate change and affecting citizens around the world, particularly issues of human security and the stability of political systems, linking teaching and research on climate change serves the long-term self-interest of states.

From this perspective, the collective discourse between social scientists and climate scientists, the impact of environmental degradation on human life and nature, the instigation of conflicts, the transformation of world politics, and global risks as universal human experiences in relation to world society and other global social models and global governance are seen as promising directions for future research and teaching.

3. Results

3.1. A New Curriculum: What and How

3.1.1. The Underlying Idea of the Curriculum

A mapping of the unprecedented crisis of climate change and universal risks that provides ideas for a new globally orientated and transdisciplinary science and education, as well as an innovative curriculum, clearly requires the representation of the nexus between legal, natural, and social sciences.

A transdisciplinary curriculum that addresses global risks and climate change must be designed with a holistic view of the planet and humanity. Global risk and climate change have three common features:

They require sustainable solution options. This consideration includes the development of future-orientated scenarios.

No state on its own can effectively cope with it. This aspect calls for global cooperation.

There is a genuine scientific dimension involved. This dimension is linked to the need to foster transdisciplinary research and teaching.

In other words, global risk and climate change do not stop at national borders; both can be effectively managed only through global cooperation, and both need to be analysed by different disciplines in collaborative research and teaching.

Science needs fundamental transformations to unite different branches under one umbrella, addressing global risk and broader scientific horizons. Transdisciplinary teaching and research are complex but effective, enabling humanity to address challenges and achieve sustainability goals.

A transdisciplinary approach to science can offer solutions to global challenges, such as climate change-related migration. Universal risks, such as environmental displacement and human security [

46], can only be adequately analysed by different disciplines in international scientific discourse. In 2020, 80 million people were displaced due to environmental degradation, the highest number since 1945 [

47]. This devastation will result in severe humanitarian crises and widespread displacement.

The United Nations International Organization for Migration [

48] predicts a rapid increase in the number of people worldwide who will be forced to move in the coming years in anticipation of, or in response to, environmental stress. This trend underscores the necessity for international cooperation to address the challenges posed by climate change effectively and the potential instability of political systems. The long-term self-interest of states in ensuring human security and the stability of the political system is evident in environmental displacement and human security.

The establishment of transdisciplinary research units at universities dealing with global risks and climate change can contribute to finding solutions to these common challenges facing humanity. Embedding science in international discourses through the establishment of such departments at universities serves the long-term self-interest of states. In this respect, science is seen here as a global public good [

49] and a source of what Joseph Nye [

50] calls soft power.

Given that no single academic discipline has all the theories, tools, and methodologies available to adequately understand and address contemporary global risks such as climate change, transdisciplinary graduate programmes and research units need to be established. Global perspectives, innovation, and transdisciplinarity combined with excellence in teaching and research are the guiding principles of this new curriculum. The criterion of transdisciplinarity can be met by the establishment of departments that operate beyond the boundaries of traditional disciplines and faculties. To facilitate this, new structures must be put in place at the institutional level within universities. The creation of transdisciplinary working departments covering a heterogeneous spectrum of disciplines such as law, natural and social sciences is fundamental to the promotion of innovation.

The subject of global risk and climate change is comprehensive and complex and covers legal, natural, and social sciences features. The presented curriculum may act as a point of reference in guiding the future efforts of universities in the fields of global risk and climate change. In general, addressing global risk and climate change requires a holistic approach to teaching and high-quality education for students. The curriculum, designed for four semesters, is described here with its basic components. As such, it is a broad guideline that can be enriched with detailed components depending on the local context of a given university. The programme concludes with a Master's thesis, and the language of instruction is English.

The thematic focus of the new transdisciplinary curriculum is global risk and climate change. Both themes are clearly interrelated and cover a wide range of subcontent. The following is an overview of global risk and climate change, followed by a discussion of the implications of global risk and climate change for teaching and research.

Risk, as stated by Ulrich Beck [

51] (p. 29), is the

anticipation of the disaster. The distinction between risk and disaster is defined by Beck ([

51] (p. 29; own translation) as follows:

"Risk is not equivocal with disaster. Risk refers to the anticipation of a disaster. Risks depend on the possibility of future events and developments; they represent a state of the world that does not (yet) exist. (…) Risks are always future events that potentially threaten us."

On the basis of the premise that global risk has a universal impact and can be effectively addressed only through the combined efforts of different disciplines, the contributions of the three scientific disciplines—legal, natural, and social sciences—are presented in an overview.

The legal sciences can bring to the curriculum an understanding of the multilateral treaties on climate change, international law, and environmental law.

The natural sciences can help raise awareness of global risks with evidence-based facts: if humanity continues on the path of overshooting planetary boundaries, the planet and humanity will experience severe and numerous disasters in the coming decades. They provide input to this curriculum with facts about planetary boundaries, limited resources, and innovative technologies to end the fossil fuel era.

The social sciences contribute by raising awareness of how to address future risk scenarios, discussing the stability of political systems, climate wars (see, e.g., [52, 53, 54, 55]), environmentally caused migration, and global governance.

The global impact of environmental, nuclear, and biodiversity risks is felt across all regions of the world and by all humanity. In his book, "World at Risk", Ulrich Beck [51, 56] draws attention to the emergence of transnational commonalities resulting from the aforementioned risks and the inability of conventional social research to adequately capture them.

Beck [

57] (pp. 84ff.) posits that conventional social categorisations are becoming less pertinent and that methodological cosmopolitanism [

58], [

51] (p. 365), [

59] (p. 124) is a requisite approach to address contemporary social dynamics and prospective developments. The field of social science has recently expanded its scope to encompass the study of global risks with social, economic, political, and environmental consequences. This shift in focus has led to the proposition that awareness of global risk may foster a sense of global citizenship, or what is popularly known as 'cosmopolitanism' (for an overview, see [60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65].

3.1.2. Implications of Global Risks for Teaching and Research

To guarantee a sustainable future, it is imperative that scientific solutions to global risks be developed through global collaboration, with input from international discourse and a novel conceptualisation of science and education. This must address social, political, economic, and environmental crises. The Global Risks and Climate Change curriculum is designed to address these issues through its transdisciplinary and global perspective in teaching and research.

Owing to the understanding that disciplinary solo efforts are not sufficient to effectively manage the teaching of global risks and climate change, the curriculum presented here is by definition transdisciplinary in content and scope. Transdisciplinarity goes beyond conventional teaching; it stands for innovation in the sense that lecturers themselves, most likely trained in specific disciplines, have to learn from teaching together with scholars from 'other' disciplines. Thus, teaching has to leave the "ivory tower" of a particular discipline. At this point, Global Studies scholars, with their long tradition of research and teaching across conventional disciplinary boundaries as outlined above, can clearly make a significant contribution to such a new curriculum.

3.1.3. Content of the Curriculum

The new curriculum consists of global risks, their likelihood, and their impact in relation to climate change. At the outset, there must be a clear overview of global risk and its interconnectedness, as outlined in the various annual Global Risks Reports published by the World Economic Forum (see, e.g., [11, 12, 66]). In recent years, environmental risks, such as climate change, have been identified as some of the most dangerous risks facing humanity. Since 2013, the World Economic Forum's [

12] Global Risks Report 2022 lists environmental risk as one of the top five global risks for humanity in terms of likelihood and impact.

In view of this priority, students should, as a matter of principle, learn about global risks, particularly environmental risks, and their interrelationship with legal, political, social, and technical aspects. Here, scholars from the legal, natural, and social sciences can address the global challenges related to environmental risk. Climate change, understood here as a concept of global risk awareness, cannot be fully analysed without reference to the notions of global warming and biodiversity loss. Each is clearly linked to the other.

Climate change has

legal implications; the most progressive environmental laws in one state will not be successful if they are not implemented in neighbouring states, world regions, or, ultimately, the entire world. Protracted negotiations have led to the signing of various multilateral treaties, such as the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit the global temperature increase to 1.5 K above preindustrial levels, or the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1997 (Kyoto Protocol) [

67]. Both multilateral treaties were signed by all countries in the world. In essence, the environmental conventions resulting from science diplomacy can be classified into two principal categories: those regulating the utilisation of natural resources and those governing the control of pollution. To date, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe [

68] has negotiated five multilateral environmental conventions, all of which are now in force. This means that students must gain expertise in legal affairs. Students should attain the ability to understand, anticipate, and integrate legal features related to global risks and climate change.

Natural scientists, who are at the forefront of gathering data and facts about climate change, offer optional solutions to urgent problems facing humanity, such as the end of fossil fuels and the switch to renewable forms of energy. Expertise in solar, wind and hydroelectric energy is needed to mitigate climate change. In this new curriculum, solar energy is seen as a key technology for reducing the negative impacts of climate change [

69].

The social sciences can contribute to political dimensions such as global governance, global models of society, and aspects of social relations. Equity is an important aspect here, as there is a link between climate change and equity. Although people in different regions of the world are affected differently by the global risk of climate change, there is a notion of shared responsibility for dealing with these challenges. Neither the impacts of climate change nor the policies to mitigate them can be fully addressed without analysing inequity within and between countries and regions.

Global Studies is a key component of the curriculum because of its long-standing expertise in transdisciplinary research and teaching. However, as mentioned above, it needs to be combined with and enriched by the legal and natural sciences. Global Studies can contribute to questions of global contexts and affairs as well as to discourses on global sustainable development (for the latter, see Wittmann et al. [

70]).

Science alone is not enough to limit the global risks associated with climate change. Scientific knowledge and expertise must be translated into policy. Given this interface between science and policy, the concept of

science diplomacy is also part of the new curriculum. In particular, environmental diplomacy (for an overview, see [71, 72, 73, 74]; [

75] (pp. 66ff.) As an integral part of science diplomacy, this study provides important insights for global politics and international relations to address climate change peacefully as a key challenge for humanity. Moreover, environmental diplomacy is understood as an area of global governance [

76] that will have a significant impact on shaping global politics, international relations, and human security as humanity is confronted with increasing environmental threats. At this point, science diplomacy can be an orchestrating factor at the intersection of environmental governance and global environmental governance. Diplomats are seen here as trained professionals who can achieve mutual understanding in complex and difficult political scenarios. They are also present, together with scientists, at United Nations conferences on climate change, for example, and can facilitate agreements between different stakeholders. Part of the curriculum is therefore dedicated to the acquisition of knowledge about the concept of science diplomacy.

Another important component of the curriculum is future-orientated teaching, which focusses on how humanity can cope with global risks caused by climate change in the coming decades. The development of future scenarios on global risks and climate change can help transform the present. Today's political decisions have far-reaching consequences for future generations. This idea is deeply rooted in the understanding of sustainability. Since the beginning of the sustainability discourse, the term has clearly referred to the notion of preserving the Earth as a livable place for humans within given planetary boundaries. Educating and motivating students to address the coming global challenges is another component of future-orientated teaching. Thus, identifying measures to increase human resilience to global challenges ahead is an integral part of this transdisciplinary area of research and teaching. The future education element of the curriculum aims to provide strategies for developing peaceful optional solutions for humanity.

The components of the programme focus on issues such as understanding global risks, climate change, environmental law and legal aspects, natural sciences and sustainable carbon-free energy solutions, social sciences and global models of society and (in)equity issues, as well as global governance, science diplomacy, and the development of future scenarios, including peaceful strategies for dealing with global risks.

The rationale for establishing this curriculum in technical universities with a focus on computing is based on the understanding that new digital technologies are a driving force for the future development of humanity and the planet and can be effectively used as tools to manage global risks and climate change.

3.2. Key Outcomes of the Curriculum for Students and Universities

The curriculum presented aims to increase the knowledge of lecturers in transdisciplinary research and teaching while enriching the holistic views of students.

The key learning outcomes for students are as follows:

Understanding the scientific basis of global risks and climate change.

Fostering global awareness and holistic views.

Forcing transdisciplinary educational outcomes throughout the curriculum.

Gaining expertise in the interconnectivity of global risks and climate change.

Understanding the basics of international law, environment-related laws, and multilateral treaties.

The skills of key technologies for the future, i.e., solar energy, should be strengthened.

Knowledge about global models of society, i.e., the framework of world society.

Understanding the system of global governance.

Awareness of the interface between science and policy via the concept of science diplomacy.

Creating resilience strategies for humanity.

Development of future scenarios for humanity and analysis of global trends.

Identifying local development needs to contribute to optional solutions to global risks.

The educational aim of the Master’s programme is to provide an academic university education for students that enables them to understand global risks and climate change on the basis of thoroughly applied transdisciplinary skills. Through the integrated teaching of general, core and specialist courses in law, the natural, and social sciences, and cross-cutting areas such as computer science, students acquire synergistic knowledge.

This innovative outcome-based curriculum, which emphasises global perspectives and transdisciplinarity, will prepare students for future scenarios related to global risks and climate change. Students will become familiar with current developments in global risk and climate change and acquire knowledge of skills and concepts to address universal environmental threats. They will gain expertise in concepts, tools, and global frameworks from the legal, natural and social sciences that will enable them to address the most urgent global risk facing the world today: climate change.

This new curriculum also aims to benefit universities. In this respect, the key outcomes for universities are as follows:

Sustainability needs transdisciplinary approaches. The transdisciplinary transfer of knowledge on sustainability relieves traditional disciplines from teaching sustainability content. Universities can outsource these topics to the transdisciplinary curriculum.

Academia offers a curriculum that meets contemporary needs for education and research. Universities that implement this curriculum can strengthen their role as designers of current international scientific debates and as actors in modern research and teaching.

Universities contribute to the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda. The establishment of the curriculum provides universities with a teaching and research area on universal challenges (climate change, migration, new digital technologies) and serves to implement the Sustainable Development Goals proposed by the UN.

Universities contribute to sustainability discourses. In terms of sustainability discourses, the curriculum can play a role in the management of global risk and provide insights into future scenarios for humanity. As such, universities can emphasise their role in responsible science for sustainability.

The establishment of the curriculum enables universities to enhance their collaboration with international organisations, regional supranational organisations, and the Federal Ministries for International Affairs. The academic community is engaged with these organisations through teaching and research, thereby facilitating the creation of synergies between politics, international policy, and academia.

Universities are well positioned to contribute to existing scientific cooperation and science diplomacy. Through teaching and research that aligns with the scientific foreign policy objectives of states and fosters scientific collaboration with the cultural agreements of states (science diplomacy), this curriculum provides states with insights for addressing global risks. It also facilitates sustainable synergy between science and the Federal Ministries for International Affairs, enhancing the integration of science and national foreign policy.

3.2.1. Strategies for Implementation

The implementation of the described curriculum is a difficult and complex task. The development of new curricula involves a variety of stakeholders and is embedded in a particular political environment and policy-making process.

The implementation of the proposed curriculum will be achieved through a process of communication with relevant stakeholders, including ministers, politicians, industry representatives, presidents, and vice-chancellors of universities. Any successful implementation of the new curriculum requires an enabling and supportive framework, both in the political and industrial spheres and at each individual university. Given these general conditions, the support of the management of a specific university for the establishment of the curriculum through institutional implementation is a conditio sine qua non for the successful realisation of the Master’s programme.

The second step can be the development of an appropriate curriculum, as outlined above, with key features. This should involve scientists from different backgrounds working together to develop a detailed curriculum that can also consider local needs for higher education. In this way, the curriculum outlined above, with its key components, can function as a central guideline that should be modified in the local context. The curriculum presented is in the tradition of a studium generale.

In terms of teaching staff, the curriculum requires lecturers who are already experienced in transdisciplinary teaching. This is a major challenge because most academics are trained along unidisciplinary lines. For successful implementation, a university must have open-minded lecturers who are willing to learn in the processes of transdisciplinary teaching.

The central assumption here is that universities that implement such a new, transdisciplinary curriculum will benefit in the long run. They attract more students than others because teaching is related to current and future global trends. Finally, the expertise gained by students in this Master’s programme can be used effectively by industry, due to the sustainability component in the programme, and by international organisations and realpolitik, due to the link between science and policy through the concept of science diplomacy.

4. Discussion

The management of global risks, most notably climate change, must be conducted in a sustainable manner. In this context, sustainability represents the antithesis of human activity, occupying a central position in the conceptual framework of education. Nevertheless, this subject is currently receiving insufficient attention in higher education. It is imperative that this situation be rectified.

Climate change is one of several global risks, albeit man-made and the most threatening to people and the planet and leads to the need to develop transdisciplinary innovation spaces at universities, as mentioned at the beginning. One tool for understanding how to mitigate global risks and climate change in a meaningful way and how to develop future strategies for addressing both in a sustainable way is education. In particular, academic courses provide insights into global risks and climate change and can help in the development of strategies for implementing sustainability. Guiding principles for a new curriculum on global risks and climate change have therefore been formulated. Adequate teaching of both issues requires transdisciplinary approaches as well as a global perspective.

A holistic view must be developed by classically trained specialists (legal, natural, and social scientists). This is a challenging task for research and teaching, which have become increasingly specialised in recent decades. A different perspective is needed to see the whole. Global Studies scholars are seen here as well trained for this purpose, since their research and teaching area clearly and by definition goes beyond traditional disciplines. It is therefore argued that Global Studies has much to contribute to a transdisciplinary Master's programme and is seen as an important component for its research and teaching.

The curriculum emphasises the importance of transdisciplinary collaboration and teamwork in addressing global risks and climate change. It encourages scholars from various fields to work together, focussing on a macro perspective rather than a micro perspective. The curriculum is not limited to a single discipline but aims to promote cooperation between legal, natural, and social sciences, fostering the development of new, groundbreaking optional solutions for sustainable development.

The content of the described curriculum includes components from the legal, natural, and social sciences in a transdisciplinary way. As such, the subjects should not be taught in isolation from each other but should be taught in joint classes. This requires openness on the part of the lecturers. Transdisciplinarity is more than adding one academic discipline to another. It goes far beyond that. Environmental risks and their interrelationship with social, political, technical, and legal aspects constitute the basic content of the curriculum. The development of future-orientated research and teaching, including the formulation of resilience strategies for humanity, has previously been identified as a key area of advanced study.

The implementation strategies are described here as the most challenging part of the proposed curriculum. Support from university managers is a prerequisite for any effective implementation of the curriculum. Implementation will require leaders with a global outlook and an awareness that research and teaching in the coming decades cannot be adequately undertaken with a parochial or provincial mindset. Conventional teaching and research along disciplinary boundaries are not capable of addressing global risks and climate change.

Science and education must develop pathways for the survival of humanity and the design of a sustainable future, replacing short-term and minor problems with universal threats. The presented transdisciplinary MSc curriculum on global risks and climate change is a key component of the impact of science for future scenarios. Education is a powerful tool for generating innovation and awareness of universal threats, creating resilience strategies for humanity to cope with global risks, and developing optional solutions for a more sustainable world.

Science-based facts about climate change require multilateralism and science diplomacy as tools for global policy to peacefully manage future risk scenarios. The timeframe for addressing the global risks posed by climate change is narrowing. In this context, a research article published in Science [

77] noted that "exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points", i.e., conditions beyond which changes in some parts of the climate system become self-sustaining. These changes could lead to sudden, irreversible, and dangerous impacts with severe consequences for humanity. In their analyses, the scientists believe that four tipping points—the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, the disappearance of tropical coral reefs, and the thawing of permafrost—will be reached for the global climate by 2030.

A unified approach to the interface between global risk and climate change is crucial, as a dystopian future is emerging with potential conflict scenarios and humanitarian crises. Climate wars are already occurring, and if unchecked, they could escalate into violent conflicts. The opportunity to mitigate these risks is limited.

In this context, education is seen as an appropriate tool for promoting peace and sustainability. Environmental and human security are critical cornerstones for the future of humanity and are increasingly becoming key issues in global politics and international relations. Climate change is not an issue of geopolitical competition; in contrast, it is an issue of the stability of political systems. It is therefore inherently a (human) security issue. From a global perspective and based on a normative approach, science diplomacy, as a component of the Master's programme presented here, can address the interplay of climate change and its connection to violent conflicts and peacebuilding. In this context, the common environmental risks associated with climate change can serve as catalysts for multilateral collaboration, thereby facilitating the mitigation of tensions, fostering confidence-building measures, and ultimately contributing to the promotion of global stability and sustainable peace (Wittmann, 2024). This will not be achievable without the presence of effective global institutions, the existence of global cooperation, and the provision of high-quality research and teaching. The input of students with global and transdisciplinary education, equipped with expertise in this field, is the optimal guarantee.

5. Conclusions

The global risks and climate change that affect all aspects of life around the world also present opportunities for the development of sustainable solution options. The fields of science and education clearly play an instrumental role in this regard.

It is imperative that sustainability be employed as a strategic concept in research and teaching rather than being utilised as a mere buzzword in academic programmes, as evidenced by instances of greenwashing. The implementation of transdisciplinarity in research and teaching is a complex undertaking that requires a certain degree of openness. The identification of universal interests and the reinforcement of the interconnectivity of global risks serve to advance the concept of cosmopolitanism.

To date, the international community has succeeded in establishing multilateral treaties to reduce global risks such as climate change, which threatens humanity. To prevent future generations from being exposed to the real hazards of mass extinction, a joint effort is needed by many stakeholders, i.e., scientists, diplomats, and politicians. The Master's programme on Global Risks and Climate Change presented here is one building block that universities can use to contribute to this effort.

Transdisciplinary teaching of global threats is a contingency plan, involving specialised experts as learners rather than trained experts. This approach offers a more expansive perspective for students. However, there is a risk of failure, as the outcome may be unfavourable. Teachers may face challenges in developing new teaching ideas and methods.

The teaching and lecturing roles within this Master's programme require scholars who are committed to entering a relatively new field of study. This will necessitate considerable discussion time between the various specialists. It will be necessary for lecturers to expand their knowledge base to teach within the broad framework provided by this programme. This whole process is complex and difficult, but it is absolutely necessary because of the urgency of dealing with existing global risks, given that the consequences of climate change are already manifesting themselves in all parts of the world.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: World Economic Forum Global Risks Perception Survey 2022-2023.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.W. and D.M.; methodology, V.W. and D.M..; software, V.W. and D.M.; validation, V.W. and D.M.; formal analysis, V.W. and D.M.; investigation, V.W. and D.M.; resources, V.W. and D.M.; data curation, V.W. and D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, V.W. and D.M.; writing—review and editing, V.W. and D.M.; visualization, D.M.; supervision, V.W. and D.M.; project administration, V.W. and D.M.; funding acquisition, V.W.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Johannes Kepler University Linz. Open access funding was provided by Johannes Kepler University Linz. Support by Johannes Kepler Open Access Publishing Fund and the federal state of Upper Austria.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All sources of data and information are given in the references.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Cronan, C. S. The Challenges of Human Population Growth. In Ecology and Ecosystem Analysis, Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 251-256. [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. G. The Next Million Years; Doubleday: Garden City, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H. The Challenge of Man's Future; Viking: New York, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- IFRC What is a disaster? 2023, May. Available online: https://www.ifrc.org/our-work/disasters-climate-and-crises/what-disaster (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Bostrom, N. & Cirkovic, M. Global Catastrophic Risks; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, N. Existential Risks: Analyzing Human Extinction Scenarios and Related Hazards. J Evol Technol 2002, 9, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Barnosky, A. , Matzke, N., Tomyia, S. et al. Has the Earth's sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature 2011, 471, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, P. S. The Bomb - The End of the World. The American Weekly of March 8, 1959, p. 8-11.

- Elder, R. K. & Gabel, J. C. Eds. The Doomsday Clock at 75; Hat & Beard: Los Angeles, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mecklin, J.; A time of unprecedented danger: It is 90 seconds to midnight - 2023 Doomsday Clock Statement. 2023, January 24, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Available online: https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/current-time/. (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report 2023. World Economic Forum, 2023. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report 2022. World Economic Forum, 2022. Available online: http://tatsigroup.com/fa/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/the-global-risks-report-2022.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Rockström, J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffen, W. et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347,1259855. https://10.1126/science.1259855.

- Richardson, K. et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Science Advances 2023, 9, eadh (2023), 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Centano, M et al. The Emergence of Global Systemic Risk. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J. et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature 2023, 619, 102-111. [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. B. Transdisciplinarity in Globalization Research: The Global Studies Framework. In Challenges of Globalization and Prospects for an Inter-civilizational World Order, I. Rossi, Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristotle. In Aristotle: Metaphysics Theta, S. Makin, Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006.

- Buzan, B. From International to World Society? English School Theory and the Social Structure of Globalization. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Buzan, B. An Introduction to the English School of International Relations: The Societal Approach, John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, USA, 2014.

- Bull, H. & Watson, A. The Expansion of International Society; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, K. Transnationale Politik. Zu einer Theorie der multinationalen Politik. In Die anachronistische

Souveränität. Zum Verhältnis von Innen- und Außenpolitik, E. Czempiel, Ed. ; Politische Vierteljahresschrift.

Westdeutscher Verlag: Köln/Opladen, Germany, 1969; Special Edition 1, pp. 80-109.

- Albrow, M. The Global Age: State and Society Beyond Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, J. W. World Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N. Theory of Society, Vol. 1.; Series: Cultural Memory in the Present. Translated by Rhodes Barrett. Stanford University Press: Stanford, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N. Theory of Society, Volume 2; Series: Cultural Memory in the Present. Translated by Rhodes Barrett. Stanford University Press: Stanford, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, V. Weltgesellschaft: Rekonstruktion eines wissenschaftlichen Diskurses. Studien zur Politischen Soziologie, Band 27, Nomos Verlag: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, V. Weltgesellschaft. In Kleines Lexikon der Politik, 6th ed.; D. Nohlen & F. Grotz, Ed.; C.H. Beck: München, Germany, 2015; pp. 734–736. [Google Scholar]

- Juniper, T. The Science of our Changing Planet: From Global Warming to Sustainable Development; DK: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, D. Net Zero: How We Stop Causing Climate Change; William Collins: London 2020.

- Rich, N. Losing Earth: The Decade We Could Have Stopped Climate Change; Picador: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hawken, P. Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming; Penguin Books: New York, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace-Wells, D. The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming; , Tim Duggan: New York, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. H. , Meadows, D. L., Randers, J. & Behrens, W. W III. The Limits to Growth. A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Potomac Associates–Universe Books: New York, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weizsäcker, Von E. U. & Wijkman, A. Come on! Capitalism, Short-termism, Population and the Destruction of the Planet; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, V. Global Warming and the Concepts of World Society. The Coincidence of Epistemological and Political Challenges. In After Globalization: The Future of World Society, 1st ed.; C. Suter & P. Ziltener, Eds.; World Society Foundation volume, 2024. World Society Studies, (22 pp. in press).

- Kennedy, P. , Messner, D. & Nuscheler, F. Global Trends and Global Governance; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, T. G. Global Governance: Why? What? Whither?; 1st ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, T. G. & Wilkinson, R. Eds. Global Governance Futures; Routledge: London and New York, UK and USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Claros, A. , Dahl, A. L. & Groff, M. Global Governance and the Emergence of Global Institutions for the 21st Century; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zürn, M. A Theory of Global Governance: Authority, Legitimacy, and Contestation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M. N. , Pevehouse, J. C. W. & Raustiala, K. Eds.. Global Governance in a World of Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Paris Agreement. 2015, December 12. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- UN. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. A/RES/70/1. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/291/89/PDF/N1529189.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU). Welt im Wandel - Sicherheitsrisiko Klimawandel. The Map of Future Conflict Scenarios, 2007, May. Available online: https://www.wbgu.de/fileadmin/user_upload/wbgu/publikationen/hauptgutachten/hg2007/pdf/wbgu_hg2007.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- UNHCR Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2020. Report by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2021. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/media/global-trends-forced-displacement-2020 (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- United Nations. Migration Data Portal. Types of migration. Environmental Migration, 2023, June 8. Available online: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/environmental_migration_and_statistics (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Boulton, G. S.; Science as a Global Public Good. International Science Council Position Paper. 2021, November. Available online: https://council.science/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ScienceAsAPublicGood-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Nye, J. S. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics; PublicAffairs: New York, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Weltrisikogesellschaft; Suhrkamp Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, G. Climate Wars. The Fight for Survival as the World Overheats; Oneworld Publications: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M. E. The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet; PublicAffairs: New York, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Welzer, H. Climate Wars: What People Will Be Killed in the Twenty-First Century; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G. Climate Wars. Policy, Politics, and the Environment; Council on Foreign Relations Press: New York, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. World at Risk; 1st ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008.

- Beck, U. Macht und Gegenmacht im globalen Zeitalter; Suhrkamp Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. , & Sznaider, N. Unpacking cosmopolitanism for the social sciences: a research agenda. Br J Sociol 2006, 57, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berking, H. Globalisierung. In Handbuch Soziologie, N. Baur, H. Korte, M. Löw & M. Schroer, Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008; pp. 117-137. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G. W. & Held, D. Eds. The Cosmopolitanism Reader; 1st ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty, D. , Bhaba, H. K., Pollock, S. & Breckenridge, C. A. Eds. Cosmopolitanism; Duke University Press: Durham and London, UK 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanty, G., Ed. Routledge Handbook of Cosmopolitanism Studies, ; 1st ed.; Routledge: London and New York, UK and USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Fine, R. Cosmopolitanism. Key Ideas; 1st ed.; Routledge: London and New York, UK and USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, G. , Woodward, I. & Skrbis, Z. The Sociology of Cosmopolitanism: Globalization, Identity, Culture and Government; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovisco, M. & Nowicka, M. Eds. The Ashgate Research Companion to Cosmopolitanism; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report 2024. World Economic Forum, 2024. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2024.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 1997, December 10, FCCC/CP/1997/L.7/Add.1. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/docs/cop3/l07a01.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- UNECE Multilateral environmental agreements. //UNECE – United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2023. Available online: https://unece.org/about-5 (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Wittmann, V. & Meissner, D. The Nexus of Energy for Free and World Society. Intern J Sust Energy Development 2019, 7, 384-391. [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, V., Arici, E. & Meissner, D. The Nexus of World Electricity and Global Sustainable Development. Energies 2021, 14:5843. [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. E. & Ali, S. H. Environmental Diplomacy: Negotiating More Effective Global Agreements; 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, F. & Spence, C. Eds. Heroes of Environmental Diplomacy: Profiles in Courage; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuokkanen, T. , Couzens, E., Honkonen, T. & Lewis, M. Eds. International Environmental Law-making and Diplomacy: Insights and Overviews; Routledge: London and New York, UK and USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, L. & Kallab, E. Effective Forms of Environmental Diplomacy; Routledge: London and New York, UK and USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjola, C. & Kornprobst, M. Understanding International Diplomacy: Theory, Practice and Ethics; 2nd ed.; Routledge: London and New York, UK and USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A. F. , Hocking, B. & Maley, W. Eds. Global Governance and Diplomacy. Worlds Apart? Studies in Diplomacy and International Relations; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong McKay, D. I. , Staal, A., Abrams, J. F., Winkelmann, R., Sakschewski, B., Loriani, S., Fetzer, I., Cornell, S. E., Rockström, J. & Lento, T. M. Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science 2022, 377, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).