Submitted:

17 August 2024

Posted:

19 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Period

2.2. Study Design and Sampling

2.3. Primary Culture, Isolation and Identification

2.4. Determination of MIC

2.4.1. Selection of Agar

2.4.2. Preparation of Stock Solution

2.4.3. Preparation of Working Solutions

2.4.4. Preparation of Bacterial Inoculum

2.4.5. Experimental Design

2.4.6. Reading of Results

2.5. Data Storage and Analysis

3. Results

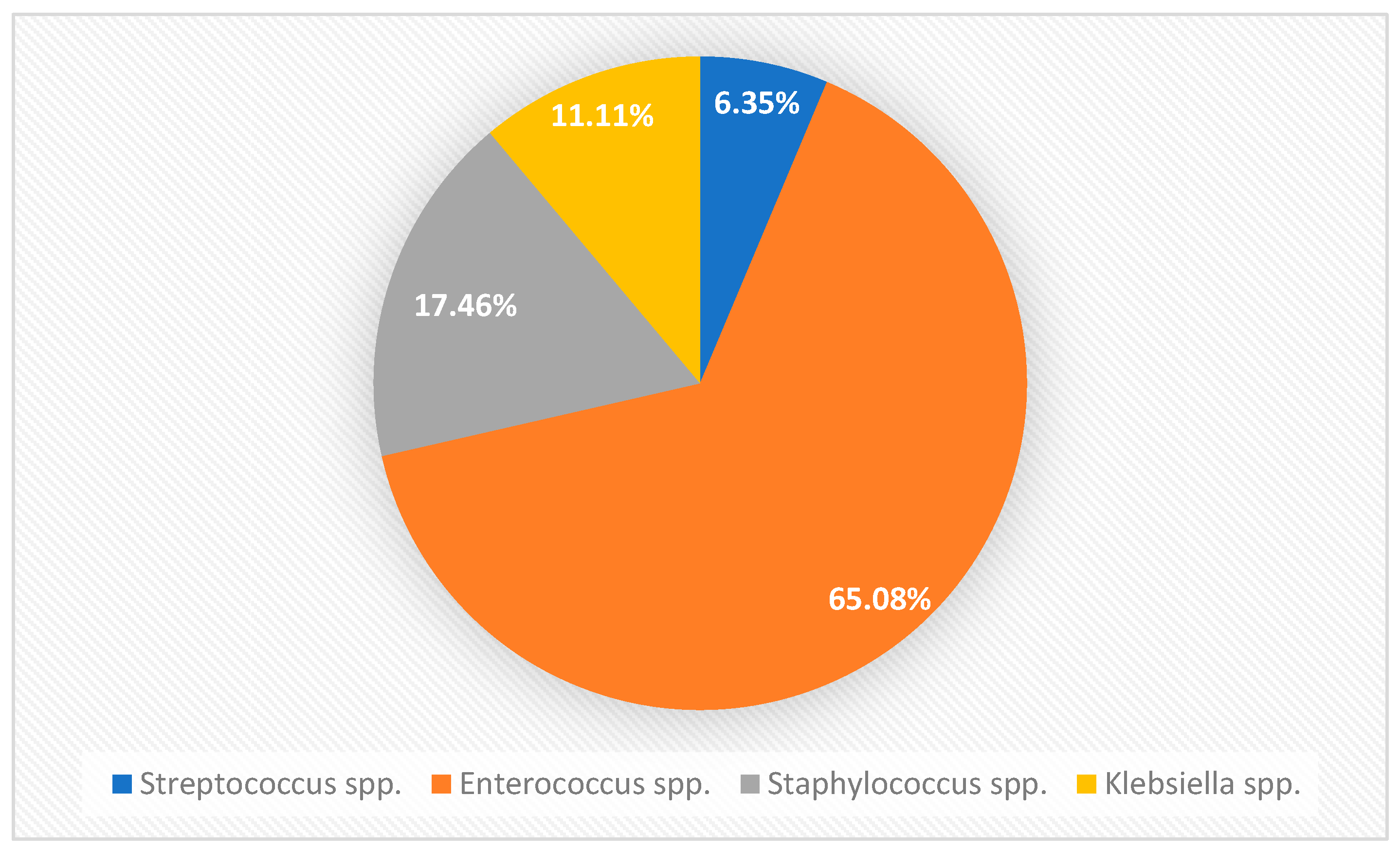

3.1. Prevalence of Bacterial Species

3.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) of Different Antibacterials against Bacterial pyometra Isolates

3.3. In Vitro Susceptibility and Potency Estimation of Bacteria pyometra Isolates to Different Antibiotics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical consideration statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aminov, R.I. A Brief History of the Antibiotic Era: Lessons Learned and Challenges for the Future. Front. Microbiol. 2010, 1, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.P.; Yates, K.A.; Romanowski, E.G.; Karenchak, L.M.; Mah, F.S.; Gordon, Y.J. An Ophthalmologist’s Guide to Understanding Antibiotic Susceptibility and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration Data. Ophthalmology 2005, 112, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.M. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 49, 1049–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska-Krochmal, B.; Dudek-Wicher, R. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Antibiotics: Methods, Interpretation, Clinical Relevance. Pathogens 2021, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, I.; Huang, L.; Hao, H.; Sanders, P.; Yuan, Z. Application of PK/PD Modeling in Veterinary Field: Dose Optimization and Drug Resistance Prediction. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 5465678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gascón, A.; Solinís, M.Á.; Isla, A. The Role of PK/PD Analysis in the Development and Evaluation of Antimicrobials. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egenvall, A.; Hagman, R.; Bonnett, B.N.; Hedhammar, A.; Olson, P.; Lagerstedt, A.S. Breed Risk of Pyometra in Insured Dogs in Sweden. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2001, 15, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marretta, S.M.; Matthiesen, D.T.; Nichols, R. Pyometra and Its Complications. Probl. Vet. Med. 1989, 1, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okano, S.; Tagawa, M.; Takase, K. Relationship of the Blood Endotoxin Concentration and Prognosis in Dogs with Pyometra. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1998, 60, 1265–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassessar, V.; Verma, Y.; Swamy, M. Antibiogram of Bacterial Species Isolated from Canine Pyometra. Vet. World 2013, 6, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, A.-T.; Huang, W.-H.; Wang, S.-L. BACTERIAL ISOLATION AND ANTIBIOTIC SELECTION AFTER OVARIOHYSTERECTOMY OF CANINE PYOMETRA: A RETROSPECTIVE STUDY OF 55 CASES. Taiwan Vet. J. 2020, 46, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, M.; Kafle, S.; Gompo, T.R.; Khatri, K.B.; Aryal, A. Microbiological and Hematological Aspects of Canine Pyometra and Associated Risk Factors. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robaj, A.; Sylejmani, I.; Hamidi, A. Occurrence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Bacterial Agents of Canine Pyometra. Indian J. Anim. Res. 2018, 52, 394–400. [Google Scholar]

- kumari Baithalu, R.; Maharana, B.R.; Mishra, C.; Sarangi, L.; Samal, L. Canine Pyometra. Vet. World 2010, 3, 340. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoskova, A.; Vitasek, R.; Leva, L.; Faldyna, M. Hysterectomy Leads to Fast Improvement of Haematological and Immunological Parameters in Bitches with Pyometra. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2007, 48, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagman, R. Pyometra in Small Animals 2.0. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2022, 52, 631–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkki, O.M.; Sunesson, K.W.; den Hertog, E.; Varjonen, K. Postoperative Complications and Antibiotic Use in Dogs with Pyometra: A Retrospective Review of 140 Cases (2019). Acta Vet. Scand. 2023, 65, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossum, T.W.; Duprey, L.P.; O’Connor, D. Small Animal Surgery; 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Boston, MA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-323-04439-4.

- Tobias, K.M.; Johnston, S.A. Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal. No Title 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine: Diseases of the Dog and the Cat; Ettinger, S.J., Feldman, E.C., Côté, E., Eds.; Eighth edition.; Elsevier: St. Louis, Missouri, 2017; ISBN 978-0-323-31211-0.

- Hagman, R. Canine Pyometra: What Is New? Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2017, 52, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fieni, F.; Topie, E.; Gogny, A. Medical Treatment for Pyometra in Dogs. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2014, 49, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavin, L.E.; Maki, L.C. Antimicrobial Use in the Surgical Treatment of Canine Pyometra: A Questionnaire Survey of Arizona-Licensed Veterinarians. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeff, D.; Brian Lucas, H. Canine Pyometra: Early Recognition and Diagnosis. Available online: https://www.dvm360.com/view/canine-pyometra-early-recognition-and-diagnosis (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Pomba, C.; Belas, A.; Menezes, J.; Marques, C. The Public Health Risk of Companion Animal to Human Transmission of Antimicrobial Resistance During Different Types of Animal Infection. In Proceedings of the Advances in Animal Health, Medicine and Production; Freitas Duarte, A., Lopes da Costa, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 265–278.

- Heffernan, A.J.; Sime, F.B.; Lipman, J.; Roberts, J.A. Individualising Therapy to Minimize Bacterial Multidrug Resistance. Drugs 2018, 78, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnidge, J.; Paterson, D.L. Setting and Revising Antibacterial Susceptibility Breakpoints. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 391–408, table of contents. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, M.; Heuer, C.; Hussein, H.; McDougall, S. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Selected Antimicrobials against Escherichia Coli and Trueperella Pyogenes of Bovine Uterine Origin. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 4427–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, K.P.; Wilson, R.T. Antimicrobial Resistance in Nepal. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantón, R.; Morosini, M.-I. Emergence and Spread of Antibiotic Resistance Following Exposure to Antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaidarous, M.; Alanazi, M.; Abdel-Hadi, A. Isolation, Identification, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Bacteria Associated with Waterpipe Contaminants in Selected Area of Saudi Arabia. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 8042603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegand, I.; Hilpert, K.; Hancock, R.E.W. Agar and Broth Dilution Methods to Determine the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of Antimicrobial Substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute: CLSI Guidelines. Available online: https://clsi.org/ (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Hasselmann, C. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) of Antibacterial Agents by Broth Dilution. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2003, 9. [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) of Antibacterial Agents by Broth Dilution. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2003, 9, ix–xv. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, S.; Silley, P.; Simjee, S.; Woodford, N.; van Duijkeren, E.; Johnson, A.P.; Gaastra, W. Assessing the Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Bacteria Obtained from Animals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, C.E.; De Carli, S.; Riboldi, C.I.; De Lorenzo, C.; Panziera, W.; Driemeier, D.; Siqueira, F.M. Pet Pyometra: Correlating Bacteria Pathogenicity to Endometrial Histological Changes. Pathog. Basel Switz. 2021, 10, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateus, L.; Henriques, S.; Merino, C.; Pomba, C.; Lopes da Costa, L.; Silva, E. Virulence Genotypes of Escherichia Coli Canine Isolates from Pyometra, Cystitis and Fecal Origin. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 166, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyaert, H.; Morrissey, I.; de Jong, A.; El Garch, F.; Klein, U.; Ludwig, C.; Thiry, J.; Youala, M. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Monitoring of Bacterial Pathogens Isolated from Urinary Tract Infections in Dogs and Cats Across Europe: ComPath Results. Microb. Drug Resist. Larchmt. N 2017, 23, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, C.-L.; Charlebois, A.; Masson, L.; Archambault, M. Characterization of Hospital-Associated Lineages of Ampicillin-Resistant Enterococcus Faecium from Clinical Cases in Dogs and Humans. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feßler, A.T.; Scholtzek, A.D.; Schug, A.R.; Kohn, B.; Weingart, C.; Hanke, D.; Schink, A.-K.; Bethe, A.; Lübke-Becker, A.; Schwarz, S. Antimicrobial and Biocide Resistance among Canine and Feline Enterococcus Faecalis, Enterococcus Faecium, Escherichia Coli, Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter Baumannii Isolates from Diagnostic Submissions. Antibiot. Basel Switz. 2022, 11, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanishi, I.; Iyori, K.; Také, A.; Asahina, R.; Tsunoi, M.; Hirano, R.; Uchiyama, J.; Toyoda, Y.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Hayashi, S. Antibiotic-Resistant Status and Pathogenic Clonal Complex of Canine Streptococcus Canis-Associated Deep Pyoderma. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinks, M.R.; Miller, E.J.; Diaz-Campos, D.; Mollenkopf, D.F.; Newbold, G.; Gemensky-Metzler, A.; Chandler, H.L. Using Minimum Inhibitory Concentration Values of Common Topical Antibiotics to Investigate Emerging Antibiotic Resistance: A Retrospective Study of 134 Dogs and 20 Horses with Ulcerative Keratitis. Vet. Ophthalmol. 2020, 23, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyfe, C.; Grossman, T.H.; Kerstein, K.; Sutcliffe, J. Resistance to Macrolide Antibiotics in Public Health Pathogens. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a025395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganière, J.P.; Médaille, C.; Limet, A.; Ruvoen, N.; André-Fontaine, G. Antimicrobial Activity of Enrofloxacin against Staphylococcus Intermedius Strains Isolated from Canine Pyodermas. Vet. Dermatol. 2001, 12, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awji, E.G.; Tassew, D.D.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, S.-J.; Choi, M.-J.; Reza, M.A.; Rhee, M.-H.; Kim, T.-H.; Park, S.-C. Comparative Mutant Prevention Concentration and Mechanism of Resistance to Veterinary Fluoroquinolones in Staphylococcus Pseudintermedius. Vet. Dermatol. 2012, 23, 376–380, e68-69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Dai, H.; Zhang, H.; Song, Y.; An, Q.; Wang, J.; Xia, Z. Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae Complex From Clinical Dogs and Cats in China: Molecular Characteristics, Phylogroups, and Hypervirulence-Associated Determinants. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 816415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadiya, H.D.; Patel, D.M.; Ghodasara, D.J.; Bhanderi, B.B. Canine Pyometra: Clinico-Diagnostic, Microbial, Gross and Histopathological Evaluation. Indian J. Vet. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 17, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- García-Solache, M.; Rice, L.B. The Enterococcus: A Model of Adaptability to Its Environment. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00058-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirichoat, A.; Flórez, A.B.; Vázquez, L.; Buppasiri, P.; Panya, M.; Lulitanond, V.; Mayo, B. Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiles of Lactic Acid Bacteria from the Human Vagina and Genetic Basis of Acquired Resistances. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, D.C.; Nahata, M.C.; Barson, W.J. Ceftriaxone: A Third-Generation Cephalosporin. Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm. 1985, 19, 900–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Ye, Y.; Lan, P.; Han, X.; Quan, J.; Zhou, M.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, Y. Prevalence and Characteristics of Ceftriaxone-Resistant Salmonella in Children’s Hospital in Hangzhou, China. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 764787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antimicrobial conc. In stock solution |

Volume of stock solution |

Volume of distilled water |

Antimicrobial concn. Obtained (mg/L) |

Final concentration after adding. 19 ml Agar |

| 10240 | 1 | 0 | 10240 | 512 |

| 10240 | 1 | 1 | 5120 | 256 |

| 10240 | 1 | 3 | 2560 | 128 |

| 2560 | 1 | 1 | 1280 | 64 |

| 2560 | 1 | 3 | 640 | 32 |

| 2560 | 1 | 7 | 320 | 16 |

| 320 | 1 | 1 | 160 | 8 |

| 320 | 1 | 3 | 80 | 4 |

| 320 | 1 | 7 | 40 | 2 |

| 40 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 1 |

| 40 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 0.5 |

| 40 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 0.25 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 2.5 | 0.125 |

| 5 | 1 | 3 | 1.25 | 0.06 |

| 5 | 1 | 7 | 0.625 | 0.03 |

| 0.625 | 1 | 1 | 0.3125 | 0.015 |

| 0.625 | 1 | 3 | 0.1562 | 0.008 |

| 0.625 | 1 | 7 | 0.0781 | 0.004 |

| Sulfadimidine+Trimethoprim (5:1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | n | MIC Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | Mean MIC rank* | CLSI Breakpoint | Resistivity |

| Enterococcus | 41 | 0.25-64 | 2 | 8 | 200.34 | ≤1 | 23(56.10%) |

| Klebsiella | 7 | 1 to 4 | 2 | 2 | 41.50 | ≤2 | 2(28.57%) |

| Staphylococcus | 11 | 1 to 16 | 2 | 4 | 66.36 | ≤2 | 5(45.45%) |

| Streptococcus | 4 | 0.25-8 | 0.25 | 8 | 21.13 | N/A | NA |

| Ampicillin | |||||||

| Enterococcus | 41 | 0.03-2 | 0.5 | 2 | 200.34 | ≤8 | 0(0%) |

| Klebsiella | 7 | 0.03-2 | 0.5 | 2 | 26.71 | ≤8 | 0(0%) |

| Staphylococcus | 11 | 0.25-1 | 0.25 | 1 | 44.94 | ≤0.12 | 11(100%) |

| Streptococcus | 4 | 0.015-0.5 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 9.00 | ≤0.25 | 1(25%) |

| Ceftriaxone | |||||||

| Enterococcus | 41 | 0.25-32 | 8 | 32 | 237.18 | ≤1 | 31(75.61%) |

| Klebsiella | 7 | 8-32 | 16 | 32 | 52.00 | ≤1 | 7(100%) |

| Staphylococcus | 11 | 2-64 | 64 | 64 | 79.64 | N/A | 11(100%) |

| Streptococcus | 4 | 1-64 | 8 | 64 | 28.50 | ≤0.5 | 4(100%) |

| Azithromycin | |||||||

| Enterococcus | 41 | 0.06-32 | 1 | 4 | 164.02 | ≤16 | 1(2.44%) |

| Klebsiella | 7 | 0.25-4 | 1 | 4 | 36.43 | ≤16 | 0(0%) |

| Staphylococcus | 11 | 0.125-8 | 0.5 | 8 | 52.18 | ≤2 | 3(27.27%) |

| Streptococcus | 4 | 0.5-4 | 0.5 | 2 | 21.63 | ≤0.5 | 2(50%) |

| Doxycycline | |||||||

| Enterococcus | 41 | 8-128 | 32 | 64 | 294.61 | ≤4 | 41(100%) |

| Klebsiella | 7 | 0.25-1 | 1 | 1 | 29.36 | ≤4 | 0(0%) |

| Staphylococcus | 11 | 1 to 4 | 1 | 4 | 59.25 | ≤4 | 0(0%) |

| Streptococcus | 4 | 1 to 4 | 1 | 4 | 24.25 | ≤2 | 0(0%) |

| Enrofloxacin | |||||||

| Enterococcus | 41 | 0.015-0.125 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 47.91 | ≤2 | 0(0%) |

| Klebsiella | 7 | 0.03-0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 9.86 | ≤2 | 0(0%) |

| Staphylococcus | 11 | 0.015-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 15.95 | ≤1 | 0(0%) |

| Streptococcus | 4 | 0.03-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 5.75 | N/A | 0(0%) |

| Amikacin | |||||||

| Enterococcus | 41 | 0.015-0.5 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 59.87 | ≤16 | 0(0%) |

| Klebsiella | 7 | 0.03-0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 8.71 | ≤16 | 0(0%) |

| Staphylococcus | 11 | 0.015-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 17.27 | N/A | 0(0%) |

| Streptococcus | 4 | 0.03-0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 7.13 | N/A | 0(0%) |

| Clindamycin | |||||||

| Enterococcus | 41 | 0.015-2 | 0.06 | 2 | 111.72 | N/A | NA |

| Klebsiella | 7 | 0.125-0.5 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 18.00 | N/A | NA |

| Staphylococcus | 11 | 0.03-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 17.77 | ≤0.5 | 0(0%) |

| Streptococcus | 4 | 0.06-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 14.63 | ≤0.25 | 2(50%) |

| Bacteria Isolated (n=tests) | Susceptibility | Potency |

|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus spp. (n=328) | E=AK=AP>AZ>ST>CR>D | E*>AK>C>AZ>AP=ST>CR>D* |

| Klebsiella spp. (n=56) | E=AK=AP=AZ=D>ST>CR | AK*>E>C>AP>D>AZ>ST>CR* |

| Staphylococcus spp. (n=88) | E=AK=C=D>AZ>ST>AP=CR | E*>AK>C>AP>AZ>D>ST>CR* |

| Streptococcus spp. (n=32) | E=AK>AP>C=D=AZ>CR | E*>AK>AP>C>ST>AZ>D>CR* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).