Submitted:

20 August 2024

Posted:

20 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

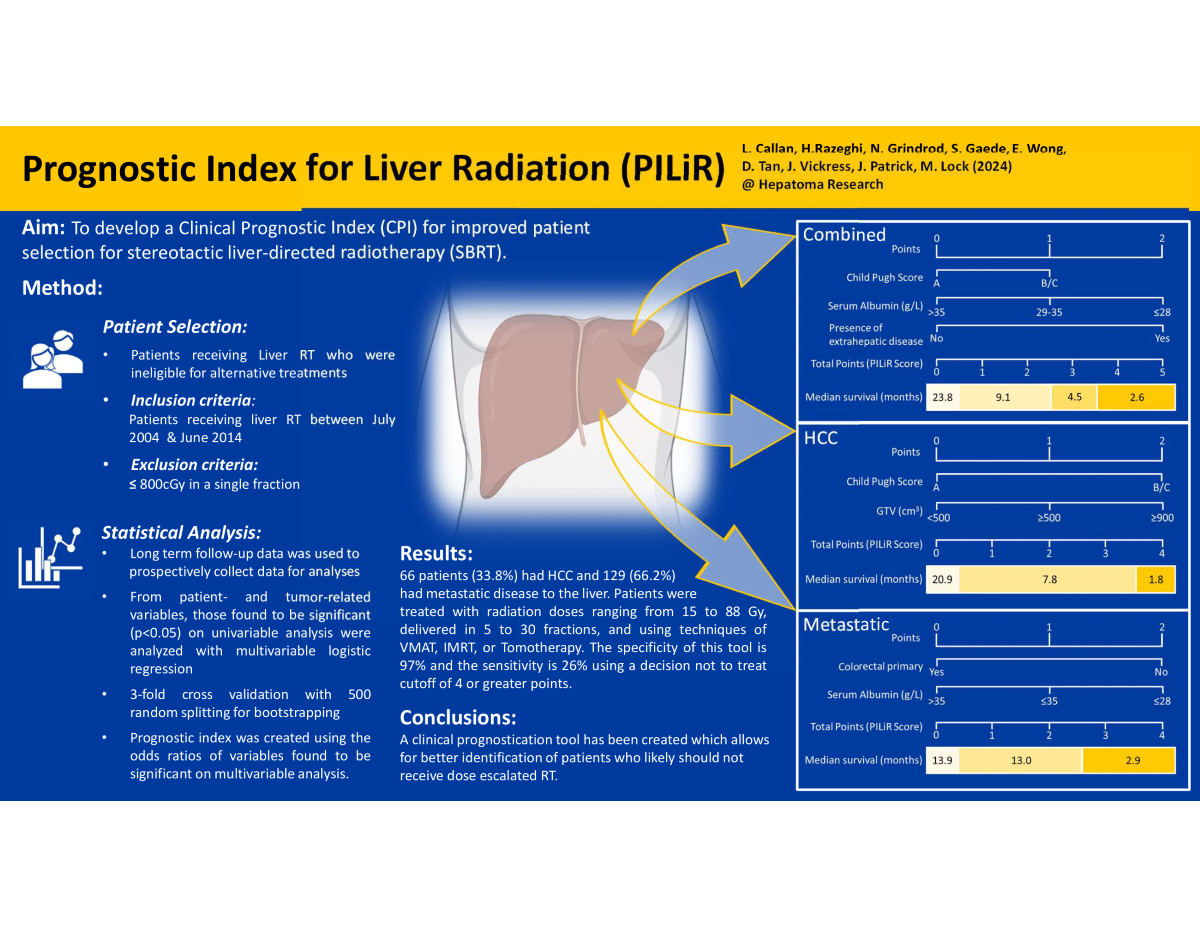

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

Study Design and Statistical Analysis

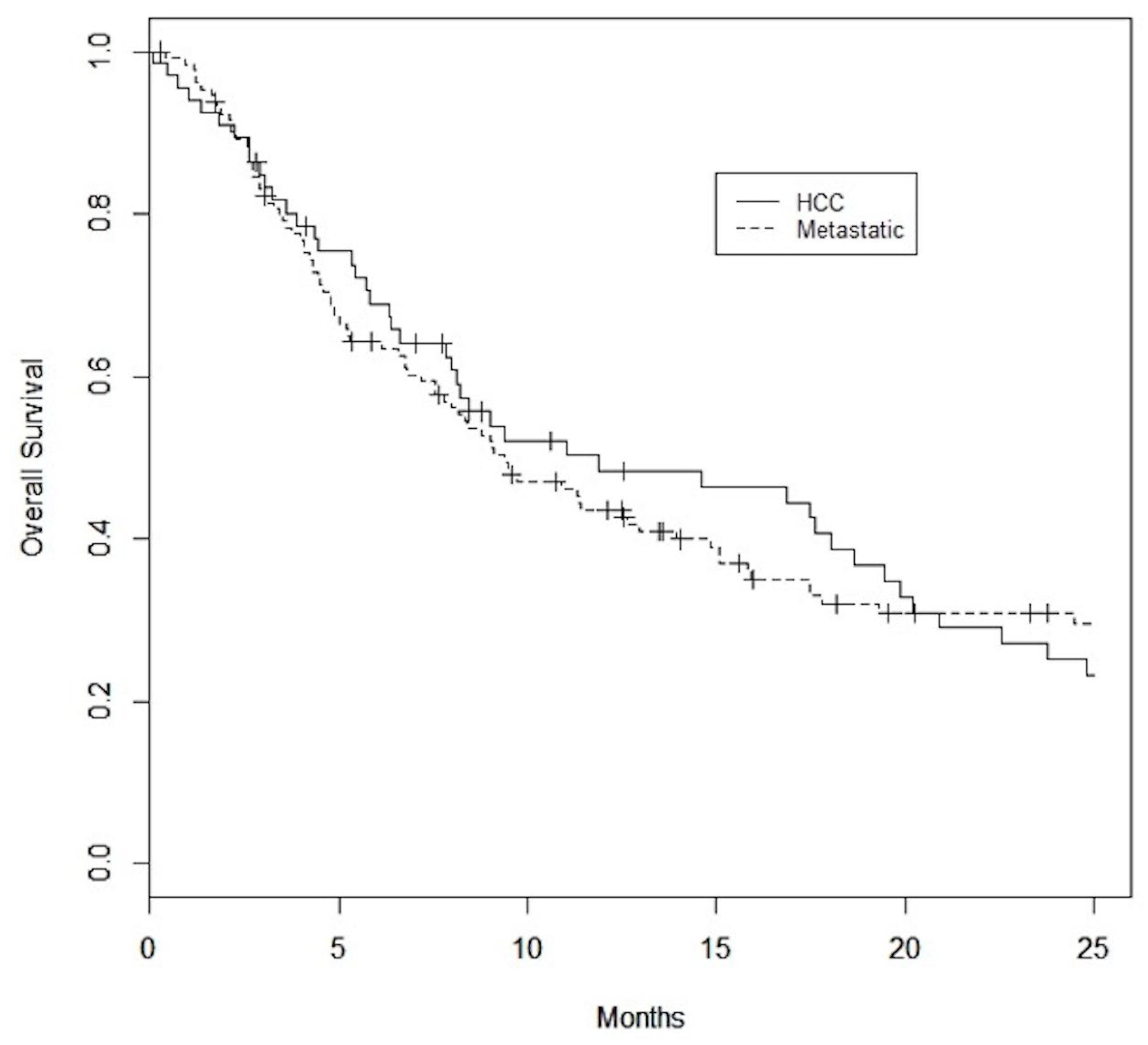

3. Results

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

Prognostic Factors

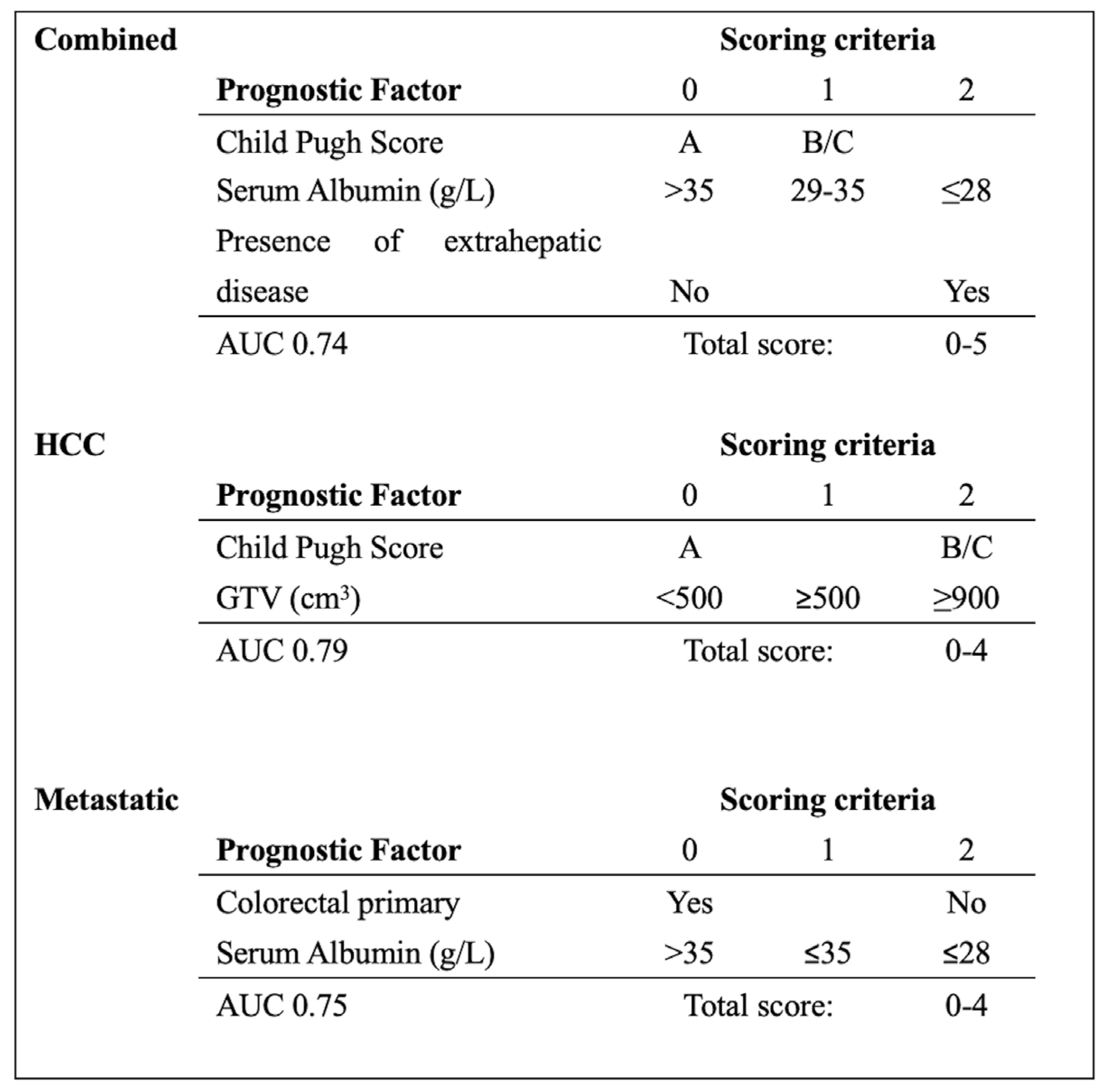

Combined Dataset

Hepatocellular Carcinoma Dataset

Metastatic Dataset

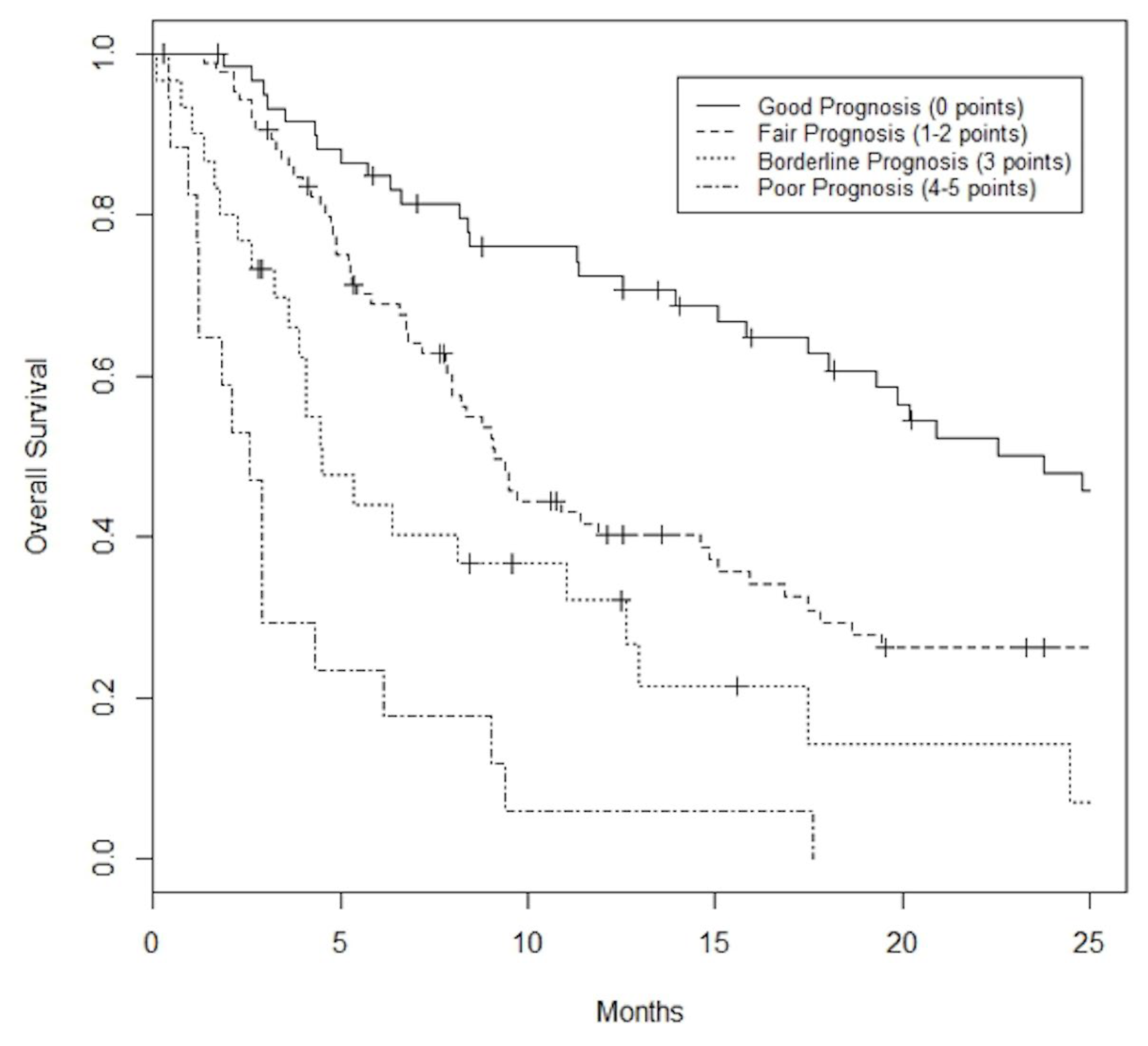

PILiR Score

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J, Group B-CLC. The Barcelona approach: Diagnosis, staging, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2004, 10, S115–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, Liu CL, Lam CM, Poon TP; et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2002, 35, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J; et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002, 359, 1734–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl DR, Stenmark MH, Tao Y, Pollom EL, Caoili EM, Lawrence TS; et al. Outcomes After Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy or Radiofrequency Ablation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2016, 34, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein J, Dawson LA, Jiang H, Kim J, Dinniwell R, Brierley J; et al. Prospective Longitudinal Assessment of Quality of Life for Liver Cancer Patients Treated With Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015, 93, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 1973, 60, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, Peine CJ, Rank J, ter Borg PJ; et al. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology 2000, 31, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C, Satomura S, Teng M, Reeves HL; et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol 2015, 33, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo CH, Liu MY, Lee MS, Yang JF, Jen YM, Lin CS; et al. Comparison Between Child-Turcotte-Pugh and Albumin-Bilirubin Scores in Assessing the Prognosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Stereotactic Ablative Radiation Therapy. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics 2017, 99, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson LA, Normolle D, Balter JM, McGinn CJ, Lawrence TS, Tenhaken RK. Analysis of radiation-induced liver disease using the Lyman NTCP model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phy 2002, 53, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress MA, Collins BT, Collins SP, Dritschilo A, Gagnon G, Unger K. Scoring system predictive of survival for patients undergoing stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver tumors. Radiat Oncol 2012, 7, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan G, Peng H, Zhou L, Jin L, Xie X, He Y; et al. A web-based nomogram model for predicting the overall survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with external beam radiation therapy: A population study based on SEER database and a Chinese cohort. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1070396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang WY, Tsai CL, Que JY, Lo CH, Lin YJ, Dai YH; et al. Development and Validation of a Nomogram for Patients with Nonmetastatic BCLC Stage C Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy. Liver Cancer 2020, 9, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li X, Ye Z, Lin S, Pang, H. Predictive factors for survival following stereotactic body radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumour thrombosis and construction of a nomogram. BMC cancer 2021, 21, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long M, Li J, He M, Qiu J, Zhang R, Liu Y; et al. Establishment and validation of a prognostic pomogram in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with intensity modulated radiotherapy: A real world study. Radiat Oncol 2023, 18, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Dewas S, Bibault JE, Mirabel X, Fumagalli I, Kramar A, Jarraya H; et al. Prognostic factors affecting local control of hepatic tumors treated by Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy. Radiation oncology (London, England) 2012, 7, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang K, Tao C, Wu F, Wu J, Rong W. A practical nomogram from the SEER database to predict the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with lymph node metastasis. Ann Palliat Med 2021, 10, 3847–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li F, Zheng T, Gu X. Prognostic risk factor analysis and nomogram construction for primary liver cancer in elderly patients based on SEER database. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e051946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Chen J, Jiang Y, Wang J, Chen S. Prognostic nomogram for hepatocellular carcinoma with fibrosis of varying degrees: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Transl Med 2020, 8, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim N, Yu JI, Park HC, Hong JY, Lim HY, Goh MJ; et al. Nomogram for predicting overall survival in patients with large (>5 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma based on real-world practice. J Liver Cancer. 2023, 23, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Zhou X, Ma J, Zhang W, Yan Z, Luo J. Nomogram for Predicting the Prognosis of Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Presenting with Pulmonary Metastasis. Cancer Manag Res 2021, 13, 2083–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendler WP, Ilhan H, Paprottka PM, Jakobs TF, Heinemann V, Bartenstein P; et al. Nomogram including pretherapeutic parameters for prediction of survival after SIRT of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Eur Radiol 2015, 25, 2693–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan QZ, Wang QJ, Dan JQ, Pan K, Li YQ, Zhang YJ; et al. A nomogram for predicting the benefit of adjuvant cytokine-induced killer cell immunotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 9202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee CW, Kim K, Chie EK, Yu SJ, Kim YJ, Yoon JH. Prognostic stratification and nomogram for survival prediction in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with radiotherapy for lymph node metastasis. Br J Radiol 2016, 89, 20160383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiner B, Pomej K, Kirstein MM, Hucke F, Finkelmeier F, Waidmann O; et al. Prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with immunotherapy – development and validation of the CRAFITY score. Journal of hepatology. 2022, 76, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco D, Oneto L. Computational intelligence identifies alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and hemoglobin levels as most predictive survival factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. Health informatics journal 2021, 27, 1460458220984205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuai L, Zhang Y, Luo Y, Li W, Li XD, Zhang HP; et al. Prognostic Nomogram for Liver Metastatic Colon Cancer Based on Histological Type, Tumor Differentiation, and Tumor Deposit: A TRIPOD Compliant Large-Scale Survival Study. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 604882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Hu C, Huang J, Xiang K, Li Z, Qu J; et al. A Prognostic Nomogram of Colon Cancer With Liver Metastasis: A Study of the US SEER Database and a Chinese Cohort. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 591009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao J, Chen Q, Deng Y, Zhao J, Bi X, Li Z; et al. Nomograms predicting primary lymph node metastases and prognosis for synchronous colorectal liver metastasis with simultaneous resection of colorectal cancer and liver metastases. Ann Palliat Med 2021, 10, 4220–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi H, Li X, Chen Z, Jiang W, Dong S, He R; et al. Nomograms for Predicting the Risk and Prognosis of Liver Metastases in Pancreatic Cancer: A Population-Based Analysis. J Pers Med 2023, 13, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ao BY, Tong F, Zhang LT, Kang YX, Wu CC, Wang QQ; et al. Risk factors, prognostic predictors, and nomograms for pancreatic cancer patients with initially diagnosed synchronous liver metastasis. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2023, 15, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao R, Dai Y, Li X, Zhu C. Construction and validation of a nomogram for non small cell lung cancer patients with liver metastases based on a population analysis. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong H, Hu D, Li M, Chen T, Jiang W, Xiang Z. Epidemiology and prognostic nomogram for esophageal cancer with liver metastasis based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Soliman H, Ringash J, Jiang H, Singh K, Kim J, Dinniwell R; et al. Phase II trial of palliative radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma and liver metastases. J Clin Oncol 2013, 31, 3980–3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson LA, Fairchild AM, Dennis K, Mahmud A, Stuckless TL, Vincent F; et al. Canadian Cancer Trials Group HE.1: A phase III study of palliative radiotherapy for symptomatic hepatocellular carcinoma and liver metastases. J Clin Oncol 2023, 41, LBA492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Pool AE, Méndez Romero A, Wunderink W, Heijmen BJ, Levendag PC, Verhoef C; et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg 2010, 97, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz AW, Carey-Sampson M, Muhs AG, Milano MT, Schell MC, Okunieff P. Hypofractionated stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for limited hepatic metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007, 67, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusthoven KE, Kavanagh BD, Gaspar LE, Schefter TE, Cardenes H, Stieber VW; et al. Multi-institutional phase I/II trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy for liver metastases. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27, 1572–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee MT, Kim JJ, Dawson LA, Dinniwell R, Brierley J, Lockwood G; et al. Phase I study of individualized stereotactic body radiotherapy of liver metastases. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27, 1585–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickress J, Lock M, Lo S, Gaede S, Leung A, Cao J; et al. A multivariable model to predict survival for patients with hepatic carcinoma or liver metastasis receiving radiotherapy. Future Oncol 2017, 13, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeridi MA, Zygogianni A, Kyrgias G, Kouvaris J, Chatziioannou S, Kelekis N; et al. Role of radiotherapy in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review. World J Hepatol 2015, 7, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperduto PW, Kased N, Bhatt A, Jensen AW, Brown PD, Shih H; et al. Summary report on the graded prognostic assessment: An accurate and facile diagnosis-specific tool to estimate survival for patients with brain metastases. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | HCC | Mets |

|---|---|---|

| (N = 66) | (N = 129) | |

| Age (years) | 70 ± 12 | 65 ± 12 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 56 (85%) | 67 (52%) |

| Female | 10 (15%) | 62 (48%) |

| Gross Tumor Volume (cm3) | 384±447 | 351±870 |

| Number of Lesions | ||

| 1 | 45 (68%) | 65 (50%) |

| 2 | 7 (11%) | 32 (25%) |

| 3 | 10 (15%) | 19 (15%) |

| >3 | 4 (6%) | 13 (10%) |

| Child-Pugh Score | ||

| A | 42 (64%) | 99 (77%) |

| B | 22 (33%) | 28 (22%) |

| C | 2 (3%) | 2 (1%) |

| Bilirubin (umol/L) | 21.6±29 | 17±32.7 |

| Serum Albumin (g/L) | 35±6 | 38±6 |

| INR | 1.36±0.79 | 1.22±0.47 |

| Extrahepatic Disease | ||

| Y | 16 (24.2%) | 73 (56.6%) |

| N | 50 (75.8%) | 56 (43.4%) |

| Ascites | ||

| Y | 19 (29%) | 12 (9%) |

| N | 47 (71%) | 117 (91%) |

| Primary Site (N = 129) | ||

| colorectal carcinoma | 52 (40%) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 22 (17%) | |

| neuroendocrine carcinoma | 10 (8%) | |

| breast carcinoma | 10 (8%) | |

| non-small cell lung carcinoma | 10 (8%) | |

| pancreatic carcinoma | 7 (5%) | |

| renal cell carcinoma | 3 (2%) | |

| metastatic melanoma | 3 (2%) | |

| gastric carcinoma | 3 (2%) | |

| esophageal | 3 (2%) | |

| Other | 6 (4%) | |

| Previous Treatments | ||

| chemo embolization | 17 (26%) | 7 (5%) |

| I-131 lipiodol | 7 (11%) | 6 (5%) |

| radiofrequency ablation | 3 (5%) | 9 (7%) |

| chemotherapy | 6 (9%) | 95 (74%) |

| liver resection | 5 (8%) | 32 (25%) |

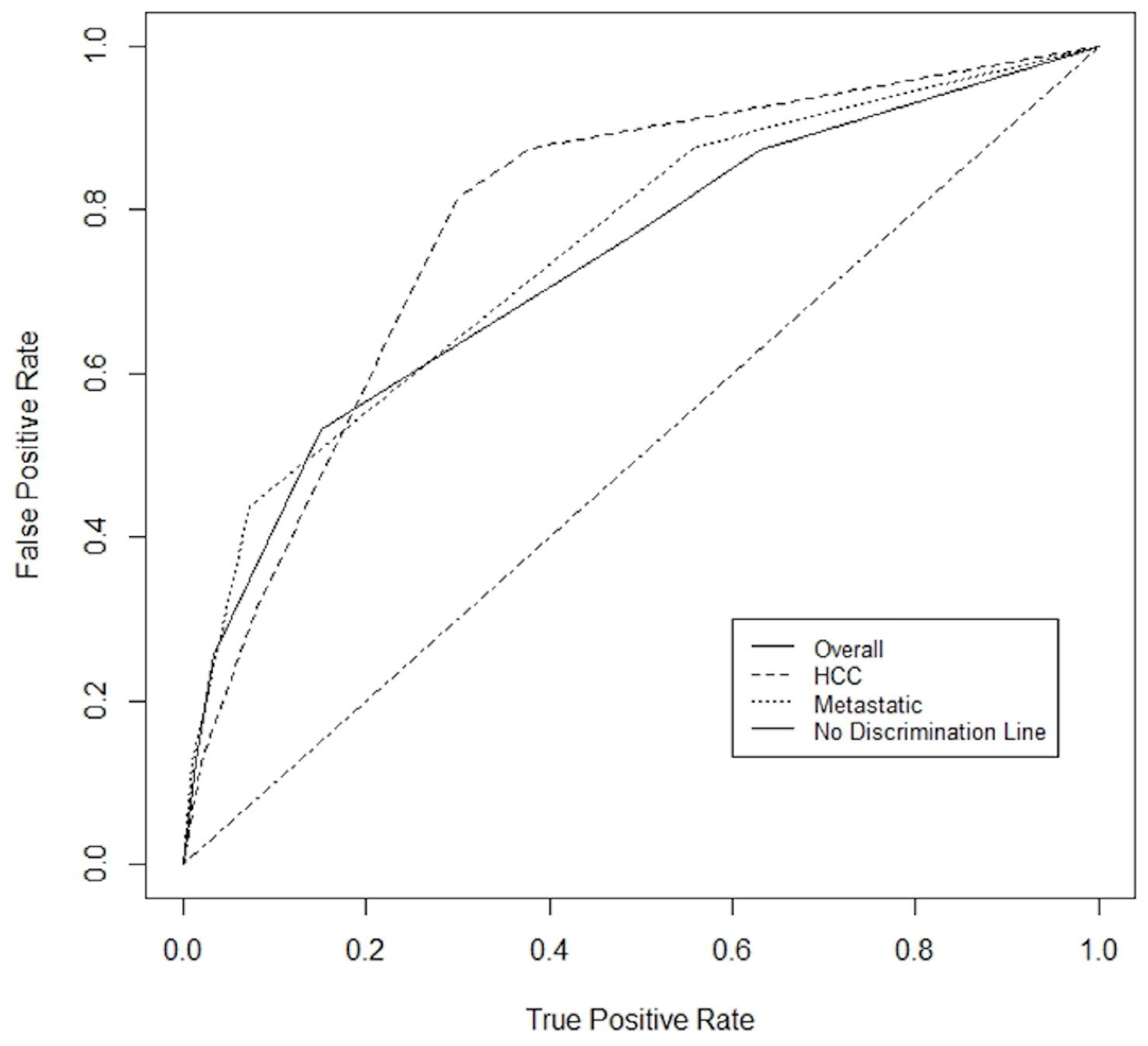

| Combined | Parameter | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Pugh Score | 0.6 | [0.40-0.82] | 0.002 | |

| Serum Albumin (g/L) | 1.1 | [1.00-1.18] | 0.039 | |

| Extrahepatic disease | 0.4 | [0.16-0.80] | 0.012 | |

| AUC 0.78 | ||||

| HCC | Parameter | OR | 95% CI | p value |

| Child Pugh Score | 0.4 | [0.22-0.66] | <0.001 | |

| GTV (100 cm3) | 0.8 | [0.70-0.96] | 0.013 | |

| AUC 0.84 | ||||

| Metastatic | Parameter | OR | 95% CI | p value |

| Serum Albumin (g/L) | 1.2 | [1.11-1.36] | <0.001 | |

| Colorectal primary | 6.7 | [1.90-23.46] | 0.003 | |

| AUC 0.80 | ||||

| Combined | Score | N | Median survival (months) | Percent living past 4 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 60 | 23.8 | 90.0 | |

| 1 | 26 | 9.0 | 80.1 | |

| 2 | 60 | 9.4 | 81.7 | |

| 3 | 30 | 4.5 | 56.7 | |

| 4 5 |

9 8 |

1.8 2.7 |

33.3 25.0 |

|

| HCC | Score | N | Median survival (months) | Percent living past 4 months |

| 0 | 33 | 20.9 | 93.9 | |

| 1 | 5 | 7.8 | 80.0 | |

| 2 | 19 | 5.7 | 57.9 | |

| 3 | 6 | 8.1 | 50.0 | |

| 4 | 3 | 1.8 | 33.3 | |

| Metastatic | Score | N | Median survival (months) | Percent living past 4 months |

| 0 | 36 | 13.9 | 91.7 | |

| 1 | 11 | 9.4 | 90.9 | |

| 2 | 61 | 14.9 | 77.0 | |

| 3 | 16 | 3.7 | 37.5 | |

| 4 | 5 | 2.1 | 20.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).