1. Introduction

In an era of intense industrialization, rapid technological development, and globalization, employees are required to work more intensely and deliver higher performance. This constant pressure for efficiency and productivity can lead to prolonged exposure to stress, which in turn reduces an individual's effectiveness and can cause negative consequences for their health, family, and social life. However, not every instance of stress is connected to the workplace. Work-related stress can be caused by various factors, and some professions are inherently more stressful than others. Professions that require human contact and quick decision-making, especially when these decisions have serious economic, social, or other impacts, are among the most stressful [

1]. Work affects health in various ways, as workplace strain is the second most common health problem, affecting approximately one-third of employees in the European Union [

2,

3].

Workplace strain includes various factors such as physical fatigue, mental pressure, work-related stress, and emotional exhaustion. These factors can lead to serious impacts on both the physical and mental health of employees. At the organizational or business level, the negative consequences may include poor overall business performance, increased absenteeism, presenteeism (cases where employees show up to work while sick and cannot function effectively), and higher rates of accidents and injuries [

4].

According to the World Health Organization, health is defined as a state of complete well-being that encompasses the physical, mental, and social dimensions of a person. It is not limited to merely the absence of disease or disability but extends to an overall sense of well-being and functionality. Health is considered a multifaceted phenomenon that integrates biological needs, mental balance, and social integration and participation [

5,

6].

With this new approach, it is understood that health is not only a matter of medical care but also a broader framework that includes psychosocial support and social justice, aiming to promote the overall well-being of individuals and communities [

7].

The nursing profession is internationally characterized by high levels of mental and physical strain, accompanied by high rates of occupational diseases and injuries. The conditions of the work environment play a crucial role in the health and safety of nurses, making this profession particularly demanding and hazardous [

8,

9].

The factors contributing to the high strain on nurses include the physical labor required for moving and caring for patients, long working hours without adequate breaks, and the constant stress associated with handling emergency situations and critical conditions. These working conditions not only increase the risk of physical injuries, such as musculoskeletal problems, but also burden the mental health of nurses, leading to higher rates of anxiety, depression, and professional burnout [

10].

Some of the most significant risks they are exposed to are psychosocial hazards, which include Work Strain [

11], Bullying [

12], Burn-Out [

13], Emotional Strain [

14], Work Life Balance) [

15], Job Satisfaction [

16], Intention to Leave [

17], Mental Health Issues [

13] and other factors that lurk in the modern work environment.

Nurses are often victims of verbal and physical violence from patients or their relatives. These experiences create a sense of insecurity and can have long-term effects on their mental health. Workplace violence is a significant psychosocial hazard that requires immediate attention and support [

18,

19]. Achieving a work-life balance is often difficult for nurses. Long shifts and the need for overtime limit the time they can dedicate to their personal lives, creating additional stress and frustration [

20,

21].

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the psychosocial risks faced by nurses. The increased demand for healthcare services, the fear of infection, and the need for heightened patient care in critical conditions further burdened the mental and physical health of nurses [

22,

23,

24,

25].

It should be noted that the presence of psychosocial risks significantly affects patient safety. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines patient safety as "the prevention of errors and adverse effects to patients associated with healthcare." There are millions of patients worldwide who suffer from disabilities, injuries, or death each year due to unsafe medical practices [

26].

The relationship between patient safety, staff well-being, and organizational culture has been recognized as vital. Understanding and improving this relationship can provide significant benefits for both patients and healthcare staff [

27,

28,

29]. The study of organizational culture can be conducted in two main ways: by approaching the organization as a whole or by analyzing the culture at different hierarchical levels or professional groups within the organization. These approaches can reveal valuable insights into how healthcare systems operate and how they can be improved to achieve better outcomes [

30,

31].

When approaching the organization as a whole, we focus on the overall prevailing culture. This approach examines the shared values, perceptions, and behavior patterns that shape the work environment. Organizational culture influences employee performance, the quality of services, and the general atmosphere within the organization [

32,

33,

34,

35]. In the healthcare sector, a positive organizational culture can encourage open communication, collaboration, and continuous improvement, thus contributing to patient safety and staff well-being [

36,

37,

38,

39].

Additionally, psychosocial risks are also linked to medication errors. More specifically, medication errors are one of the most common types of errors that occur in healthcare institutions. Morbidity from medication errors leads to high economic costs for healthcare institutions and adversely affects the quality of life of patients [

40]. In the literature, many definitions have been given for medication errors. The first definition of a medication error was recorded in 1954 by the American Hospital Association and is as follows: "The administration of the wrong drug or dose of a drug, diagnostic or therapeutic substance, to the wrong patient or at the wrong time, or the failure to administer these substances at a specific time or in the manner prescribed or considered as accepted practice." The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCCMERP) defines a medication error as: "Any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of a healthcare professional, patient, or consumer [

41,

42]. In 1960, Safren and Chapanis published the first study recording the types of medication errors, which they classified into seven categories (wrong patient, wrong time, wrong dose, omission of dose, administration of an extra dose, wrong drug, wrong route of administration) and the causes that led to them, which they classified into ten categories (failure to follow control procedures, illegible medical orders, errors in copying orders, misclassification of orders, errors in dose calculation, improvisations, wrong drug labels, assignment of patients to two nurses simultaneously, poor verbal communication, various others [

43,

44,

45,

46].

Later, a medication error is defined as a deviation from the medical order in the patient's record [

47], or any error that occurs during the medication administration process [

48]. This includes prescribing the wrong dosage, administering the wrong dose of a prescribed medication, and the healthcare provider's failure to manage or the patient's inability to swallow a medication. In addition to these categories of errors, others have been reported by various authors, including mathematical miscalculations, failure to adjust doses to prevent kidney and liver damage, failure to take an accurate history that identifies any allergies to medications, and failure to predict the interaction of two or more medications and further disseminate this information to healthcare professionals [

49].

Traditionally, nurses have been trained to use the five rights of medication administration. Specifically, these are the right medication, the right dose, the right route, the right time, and the right patient. Although these rules are generally considered basic guidelines for safe medication practice, nurses still make several errors during administration, even when following all five rights [

50,

51]. This occurs because the five rights offer limited guidance regarding medication administration. Specifically, while they provide a useful check, they focus on the performance of nurses during the final stage of medication administration and do not address the responsibility and accountability associated with medication administration or the interdisciplinary approaches to medication management [

52]. Indeed, the five rights do not focus on the complexity of the act of medication administration, significantly limiting critical thinking. Additionally, for a nurse to verify the five rights, it requires legible prescriptions, a favorable environment without constant interruptions, and adequate staffing [

53]. The consequences of medication errors can include prolonged hospitalization, the need for additional interventions, or even threaten the patient's life and lead to death [

54,

55]. In the study by Bates et al. (1997), each medication-related error was responsible for an average of 2.2 additional days of stay in the ICU [

56]. The prevention of medication errors should be a priority for professionals who either give the instructions for their administration or administer them, as their occurrence can lead to the worsening of the patient's condition, with all that entails, or even to the patient's death [

57,

58]. Studies have reported the causes of medication errors as those related to the system and those related to the individual/healthcare professional [

59,

60].

The aim of this study is to investigate the psychosocial risks experienced by nurses in tertiary hospitals in Greece and their association with their attitudes towards safety and the occurrence of medication errors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional study, based on a self-reported questionnaire, was conducted at General University Hospital Of Larissa, General Hospital of Thessaloniki G. Papanikolaou, General Hospital of Nice Agios Panteleimon - General Hospital of Western Attica Agia Varvara and Athens General Hospital O Evangelismos from September 30, 2022, to December 31, 2023.

The selection of the aforementioned hospitals was carried out by initially identifying all tertiary hospitals throughout Greece, from which those with more than 500 beds were selected. Additionally, the number of hospitalized patients exceeded 28,000 annually, and the days of hospitalization exceeded 100,000 per year. Based on the aforementioned criteria, we created three zones. Zone A included hospitals with more than 500 beds, more than 60,000 hospitalized patients per year, and more than 200,000 days of hospitalization per year. Zone B included hospitals with more than 500 beds, 28,000 to 35,000 hospitalized patients per year, and more than 100,000 days of hospitalization per year. Zone C included hospitals with more than 500 beds, 35,000 to 70,000 hospitalized patients per year, and 100,000 to 200,000 days of hospitalization per year.

Based on these created zones, the largest and smallest hospitals of each Health Region were identified, followed by their final selection for participation in the study. It should be noted that in Greece, there are seven Health Regions (Attica, Piraeus and the Aegean, Macedonia, Macedonia and Thrace, Thessaly and Central Greece, Peloponnese/Ionian Islands/Epirus/Western Greece, Crete), each encompassing all the healthcare services of the country.

The hospitals selected for the study belong to the following Zones and Health Regions: a. Evangelismos Hospital belongs to the 1st Health Region and meets the criteria of Zone A. b. Nikaia Hospital belongs to the 2nd Health Region and meets the criteria of Zone B. c. Papanikolaou Hospital belongs to the 3rd Health Region and meets the criteria of Zone C. d. The University Hospital of Larissa belongs to the 5th Health Region and meets the criteria of Zone C.

The final selection was made considering the geographical location of each hospital as well as ensuring the participation of the majority of Health Regions, with four out of the seven Health Regions participating in the study. Additionally, the hospitals selected are also the largest in their respective health regions.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The participants were nurses who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. More specifically, the inclusion criteria included: being a nurse, working in their current position for at least 12 months, being able to read and understand the Greek language, and being aged between 20 and 67 years.

The exclusion criteria were defined as: working in the hospital for a period of less than 12 months, being nursing students, being over 67 years old or under 20 years old, and not understanding the Greek language.

2.3. Data Collection / Instrument

Data collection is carried out through the completion of questionnaires by nursing staff who meet the participation criteria. The questionnaire is provided to participants in both printed and electronic form (Google Forms) at their workplace. It includes demographics of nursing staff (age, gender, marital status, work experience, level of education), characteristics of the nursing unit (pathology, surgical clinic, years of service, Intensive Care Unit), the COPSOQ III questionnaire (Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire Version III) [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65] the HSOPSC (Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture) questionnaire [

66,

67,

68], and the questionnaire for investigating nursing errors in drug administration. Additionally, a website (

https://vasileiostzen.wixsite.com/psycosocial-risks) has been created exclusively for the purposes of the study, where each participant has their own separate profile and can access details about the subject as well as the progress of the research. The collection of questionnaires was carried out during the years 2022 and 2023.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean values (Standard Deviation) and as median (interquantile range), while categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies.

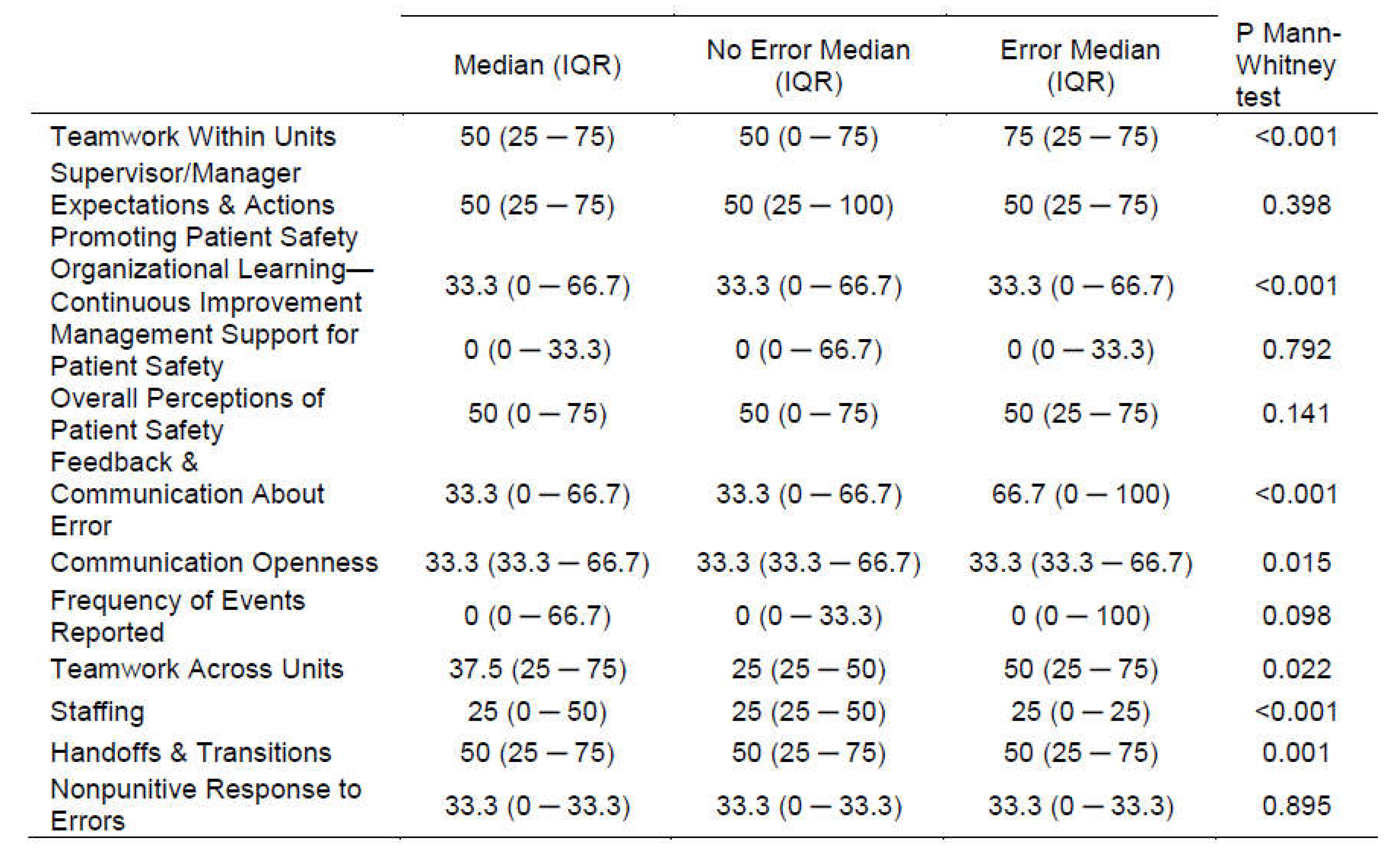

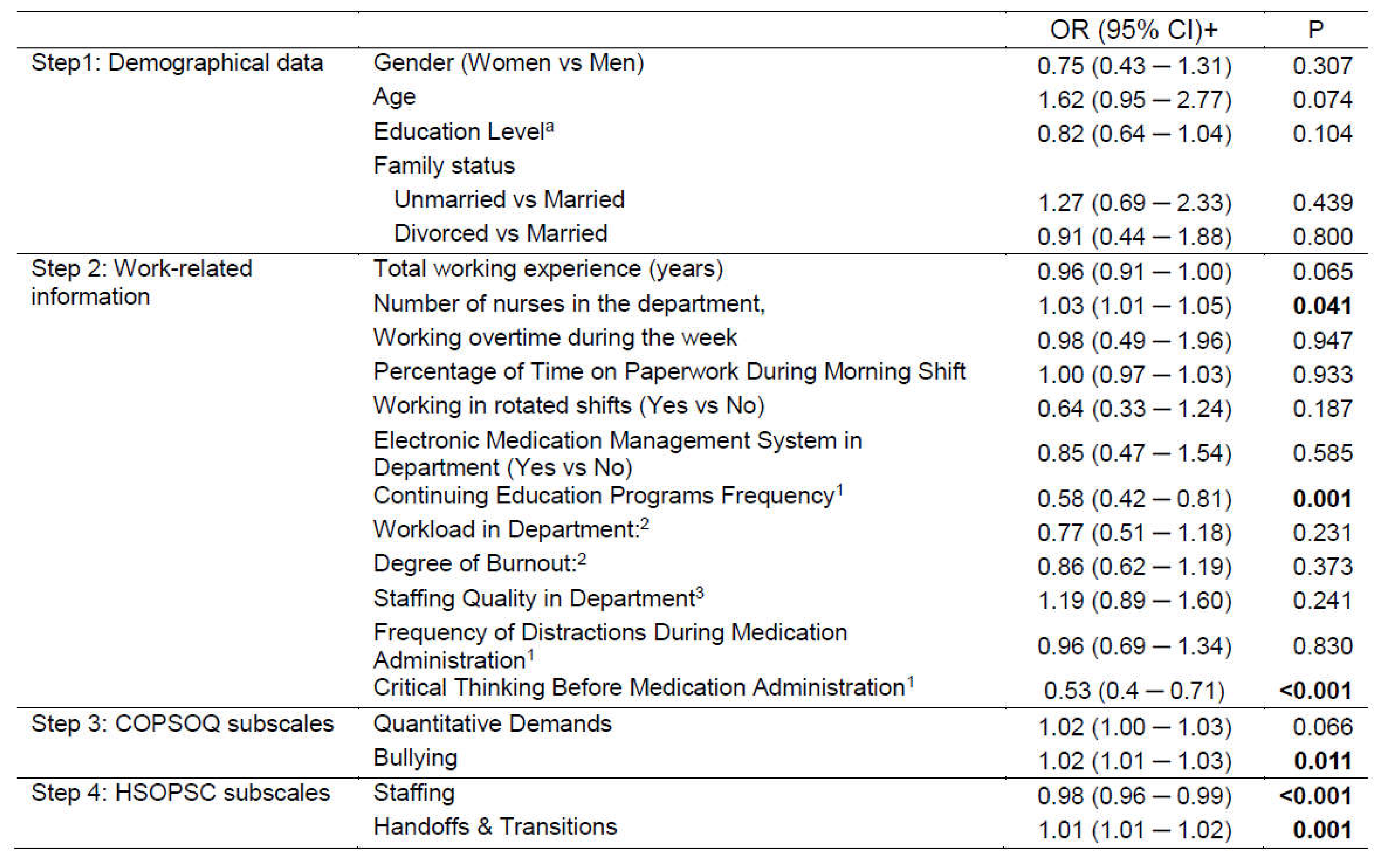

Mann-Whitney test was used for the comparison of HSOPSC and COPSOQ III subscales between participants who had realized that they had done an error in medication administration and those who had not done such an error.

A hierarchical logarithmic regression was performed with whether participants perceived they had made a mistake as the dependent variable. In the 1st step of the analysis, the demographic data of the participants was entered, using the enter method. In the 2nd step, job-related factors were entered, using the enter method. In the 3rd step, the dimensions of the psychosocial risks scale were entered, using the stepwise method (p for entry 0.05, p for removal 0.10). In the 4th step, the dimensions of the safety scale were entered, using the stepwise method (p for entry 0.05, p for removal 0.10). Odds ratios (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were computed from the results of the logistic regression analyses.

For the investigation of the mediating role of safety in the association between psychosocial risk factors and realizing that an error in medication administration had occurred, SPSS PROCESS macro was used following Hayes guidelines [

69]. A 5000-sample bootstrap procedure was used to estimate bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to test the significance of indirect effect of the relationships. Mediation is presented when the indirect effect is significant, i.e. if confidence intervals do not contain zero. According to Hayes and colleagues [

69,

70] as well as Preacher et al [

71,

72] this bootstrapping procedure overcomes the limitations of the approaches highlighted by Baron et al. [

73] and Sobel [

74] yielding results that are more accurate and less affected by sample size. Full mediation is presented when the direct effect is not significant, while partial mediation is presented when the direct effect is significant.

All reported p values are two-tailed. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 and analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software (version 26.0).

3. Results

The sample consists of 514 nurses, whose characteristics are presented in

Table 1. Females made up 74% of the participants, and 42.2% were aged 26-35 years. Additionally, 63.2% of the participants were married, and 17.4% held an MSc degree. Moreover, 52.3% of the participants worked in rotating shifts. An electronic medication management system was present in the department of 52.3% of the participants. According to 37.4% of the participants, in-hospital continuing education programs were often implemented, while 35.6% reported that such programs were rarely implemented. The workload for 53.9% of the sample was very heavy, and 42% experienced a high degree of burnout. Average staffing was reported by 40.3% of the participants, while 20.6% indicated poor staffing levels.

Regarding medication administration errors in the past year, 64.4% of the sample realized they had made an error. More specifically, 55.4% of the participants reported that they had rarely recognized making such a mistake in the past 12 months (

Table 2). Additionally, 33.7% of the participants believed that medication errors were related to administering the wrong drug, and 16% attributed errors to the wrong dose. Furthermore, 62.1% of the participants had never reported an actual medication error in the past 12 months. A total of 34.0% believed that most mistakes occurred during the afternoon shift, while 26.1% felt there was no difference between shifts. Moreover, 52.3% of participants reported the error to the physician, and 29.6% to the supervisor. A total of 54.7% of participants addressed their errors by trying to improve their training. Errors were typically dealt with through discussions, both with supervisors (77.6%) and colleagues (73%). Additionally, 41.9% of participants hid their mistakes due to fear of negative comments, and 59% because of feeling guilty.

Table 3 presents the scores on COPSOQ III dimensions for the total sample and according to whether or not they realized they had made a medication error in the past 12 months. Scores on the dimensions 'Quantitative Demands', 'Bullying', 'Gossip and Slander', 'Conflicts and Quarrels', 'Sexual Harassment', 'Physical Violence', 'Sense of Community at Work', and 'Physical Work Environment' were significantly higher in participants who realized they had made a medication error in the past 12 months. Conversely, scores on the dimensions 'Variation of Work', 'Meaning of Work', 'Predictability', 'Social Support from Colleagues', 'Bullying from Customers (External Persons)', and 'Work Engagement' were significantly lower in participants who had realized they had made a medication error in the past 12 months.

Table 4 presents the scores on the dimensions of the HSOPSC scale for the total sample and according to whether or not they realized they had made a medication error in the past 12 months. Scores on the dimensions 'Teamwork Within Units', 'Organizational Learning—Continuous Improvement', 'Feedback & Communication About Error', 'Communication Openness', 'Teamwork Across Units', and 'Handoffs & Transitions' were significantly higher in participants who realized they had made a medication error in the past 12 months. In contrast, the score on the 'Staffing' dimension was significantly lower in participants who realized they had made a medication error in the past 12 months.

Demographics were not found to be significantly related to whether participants perceived they had made a mistake (

Table 5). From the work-related information, it was found that the more nurses there were, the more likely they were to realize they had made a mistake in medication administration (OR=1.03, p=0.041). Additionally, the more frequently continuing education programs were implemented in the hospital, the lower the probability of making a mistake (OR=0.58, p=0.001), and the less often they engaged in critical thinking before executing medical medication instructions, the lower the probability of error (OR=0.53, p<0.001). In the third step, the dimensions 'Quantitative Demands' (OR=1.02, p=0.015) and 'Bullying' (OR=1.02, p=0.005) were identified as significant psychosocial risk factors, indicating that higher risks in these areas increased the likelihood of medication errors. However, when 'Staffing' and 'Handoffs & Transitions' were introduced as significant safety factors in the fourth step, the psychosocial risk factor 'Quantitative Demands' lost its significance, while 'Bullying' remained significant. The final conclusion regarding psychosocial risks and safety factors is that a higher risk of Bullying is associated with a greater probability of a medication error (OR=1.02, p=0.011), more safety in Staffing is associated with a lower likelihood of a medication error (OR=0.98, p<0.001), and more safety in Handoffs & Transitions is associated with a greater likelihood of a medication error (OR=1.01, p=0.001).

Through the PROCESS procedure, which investigates the mediating role of safety in the relationship between psychosocial risks and medication errors, it was found that the safety factors 'Staffing' and 'Handoffs & Transitions' partially mediate the relationship between 'Quantitative Demands' and medication error occurrence (significant indirect effect 'Staffing'=0.0074 with 95% CI: 0.0030 – 0.0125, significant indirect effect 'Handoffs & Transitions'=-0.0037 with 95% CI: -0.0063 – -0.0018, and significant direct effect=0.0279 with 95% CI: 0.0162 – 0.0397). However, there is no mediation in the relationship between 'Bullying' and medication errors (non-significant indirect effect of 'Staffing'=0.0004 with 95% CI: -0.0024 – 0.0037, non-significant indirect effect of 'Handoffs & Transitions'=0.0000 with 95% CI: -0.0017 – 0.0016, and significant direct effect=0.0265 with 95% CI: 0.0139 – 0.0392).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the psychosocial risks experienced by nurses in tertiary hospitals in Greece and their association with attitudes towards safety and the occurrence of medication errors. The results of our study underscore several critical findings that significantly contribute to the existing body of literature on occupational health in healthcare settings.

Primarily, the analysis indicated that nurses exposed to elevated levels of psychosocial risks, including 'Quantitative Demands', 'Bullying', 'Gossip and Slander', 'Conflicts and Quarrels', 'Sexual Harassment', 'Physical Violence', 'Sense of Community at Work', and 'Physical Work Environment', exhibited a higher propensity to report medication errors. These findings are consistent with prior research, which suggests that high-stress environments and adverse workplace interactions can markedly impair cognitive functioning and decision-making processes, thereby leading to an increased incidence of errors [

75].

Conversely, dimensions such as 'Variation of Work', 'Meaning of Work', 'Predictability', 'Social Support from Colleagues', 'Bullying from Customers (External Persons)', and 'Work Engagement' were markedly lower among participants who reported medication errors. This suggests that a supportive and predictable work environment, where nurses derive meaning from their work and receive sufficient social support, is paramount in minimizing errors. These findings corroborate the theoretical framework positing that job satisfaction and a positive work environment are fundamental to the provision of high-quality healthcare [

16,

17].

The study also determined that organizational factors play a significant role in influencing medication errors. Participants who perceived higher levels of 'Teamwork Within Units', 'Organizational Learning—Continuous Improvement', 'Feedback and Communication About Error', 'Communication Openness', 'Teamwork Across Units', and 'Handoffs and Transitions' were less likely to report errors. These findings underscore the importance of fostering a collaborative and open communication culture within healthcare settings to enhance patient safety [

76,

77].

Interestingly, the dimension of 'Staffing' was found to be significantly lower among those who reported errors, suggesting that inadequate staffing levels are a critical risk factor for medication errors. This finding is consistent with numerous studies that have shown a direct correlation between nurse staffing levels and patient safety outcomes [

78].

Through hierarchical logistic regression analysis, 'Quantitative Demands' and 'Bullying' emerged as significant psychosocial risk factors. However, when 'Staffing' and 'Handoffs and Transitions' were incorporated as safety factors, 'Quantitative Demands' lost its significance, whereas 'Bullying' remained significant. This indicates that, although workload is an important factor, the impact of bullying is more pervasive and enduring. Consequently, targeted interventions are required to address workplace bullying and promote a safe and supportive environment [

12].

The mediation analysis further elucidated the complex interplay between psychosocial risks and safety factors. 'Staffing' and 'Handoffs & Transitions' were found to partially mediate the relationship between 'Quantitative Demands' and medication error occurrence, underscoring the multifaceted nature of these issues. Effective management of staffing and transitions can mitigate the adverse effects of high work demands on error rates [

79].

Overall, the findings of this study underscore the critical need for comprehensive strategies that simultaneously address psychosocial risks and organizational safety factors to enhance both patient safety and nurse well-being. Implementing policies that ensure adequate staffing levels is paramount, as insufficient staffing has been directly linked to increased error rates and diminished quality of care. Promoting teamwork within and across units is equally essential; fostering a collaborative environment where nurses can rely on their colleagues for support can significantly reduce stress and prevent errors.

Continuous education and professional development programs are vital to keep nursing staff updated on the latest best practices and advancements in healthcare, thereby enhancing their competence and confidence in medication administration. Additionally, fostering a positive organizational culture that prioritizes open communication, mutual respect, and employee well-being is crucial. Such a culture not only enhances job satisfaction and reduces turnover rates but also improves overall patient care quality.

Further research is warranted to explore the longitudinal effects of these interventions. Long-term studies could provide valuable insights into how sustained improvements in these areas impact nurse outcomes, such as job satisfaction, mental health, and professional performance, as well as patient care quality, including error rates, patient satisfaction, and overall health outcomes. This comprehensive approach, combining immediate interventions with ongoing research, can help create safer, more effective healthcare environments for both patients and healthcare providers.

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the critical influence of psychosocial risks and organizational safety factors on the occurrence of medication errors among nurses in tertiary hospitals in Greece. The findings demonstrate that high levels of workplace stressors, such as quantitative demands and bullying, significantly correlate with an increased incidence of medication errors. Conversely, supportive and well-structured work environments characterized by effective teamwork, continuous learning, and open communication are associated with a reduction in these errors.

The necessity for comprehensive strategies that address both psychosocial and organizational aspects of the healthcare environment is evident. Ensuring adequate staffing levels is paramount, as it directly affects the workload and stress experienced by nurses. High workloads and inadequate staffing can lead to burnout and decreased vigilance, thereby increasing the likelihood of errors. By maintaining appropriate staffing levels, hospitals can alleviate some of the stressors that contribute to medication errors.

Moreover, fostering a positive organizational culture that promotes teamwork and open communication is essential. When nurses feel supported by their colleagues and have the opportunity to engage in continuous professional development, they are better equipped to handle the demands of their job effectively. This supportive environment not only improves job satisfaction and reduces turnover rates but also enhances the overall quality of patient care. Implementing policies that encourage open dialogue about errors without fear of retribution can lead to a more transparent and learning-focused culture, ultimately improving patient safety.

Interventions to mitigate workplace bullying are also crucial. Bullying creates a hostile work environment that can significantly impact mental health and job performance. Addressing bullying through targeted interventions can help create a safer and more supportive environment, reducing the occurrence of medication errors.

Future research should explore the long-term effects of these interventions on both nurse outcomes and patient care quality. Longitudinal studies could provide valuable insights into how sustained improvements in workplace conditions impact job satisfaction, mental health, and professional performance of nurses, as well as patient safety and care quality. Understanding these long-term impacts can inform the development of more effective policies and practices that promote both nurse well-being and high-quality patient care.

In conclusion, this study highlights the multifaceted nature of the challenges faced by nurses in tertiary hospitals. Addressing both psychosocial risks and organizational safety factors through comprehensive strategies is essential for enhancing patient safety and nurse well-being. By focusing on adequate staffing, promoting a positive organizational culture, and mitigating workplace bullying, healthcare institutions can create safer and more effective work environments that benefit both healthcare providers and patients.