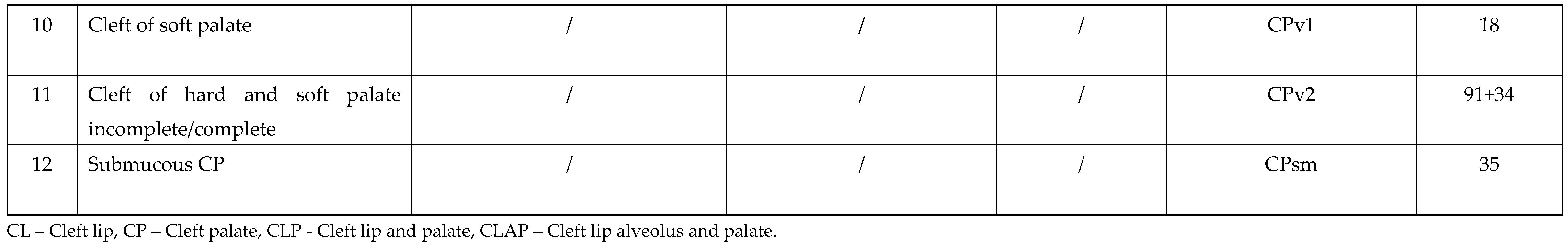

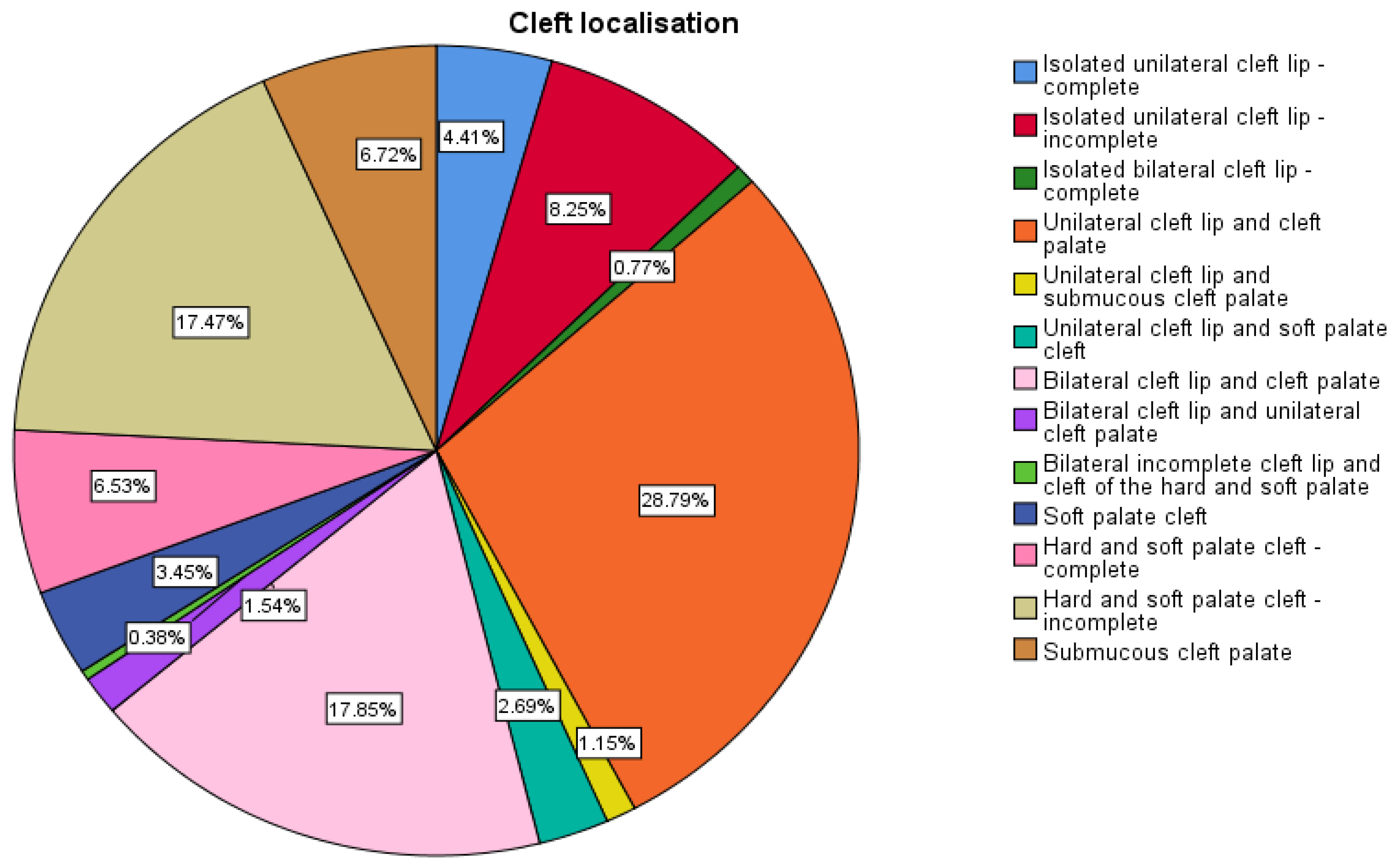

Clefts of the lip and palate (CL/P) are the most common congenital craniofacial anomalies, and the second most frequent birth defect, that constitute a heterogenous group of birth defects with multifactorial origin and various incidence among different races (1:600-1:1000) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Isolated cleft palate (CP) occurs in 1:2000 -1:2500 live births [

4,

5]. CL/P is the most common diagnosis, predominant in males, followed by isolated CP which is predominant in females [

2,

4,

5]. Unilateral clefts, involving left side are most common types of clefts, and majority of cleft lip (CL) (unilateral or bilateral) are associated with a CP [

1,

2,

4,

5,

6].

The causes of orofacial clefts remain largely unknown [

1,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Multiple environmental and genetic factors are involved in the genesis of CL/P [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

11]. Clefts can be classified as non-genetic, and genetic, which are classified as non-syndromic (70% of all clefts) and syndromic [

1,

4,

5]. They also can be classified as nonisolated (at least one unrelated defect is present), isolated (no major defects are present) and syndromic [

5,

6]. There are more than 350 Mendelian disorders associated with CLP (200 with CL and 400 with CP) [

1,

4,

5,

6,

11]. Genetic evaluation is recommended for individuals and families affected with orofacial clefts [

4,

5,

6,

7].

1.1. Treatment

Clefts represent a great burden for the patient, his family and society [

6]. Multidisciplinary approach in treatment of these patients is very important [

1,

5,

6,

7]. There is a significant difference in services and treatment protocols for children with CL/P between developed countries resulting the paucity of published randomized trials of cleft care [

4,

5,

6].

Feeding difficulties among cleft patients is well known, especially in cases with CP [

4,

5,

6]. Several cleft specific bottles (assisted-delivery-squeeze and rigid bottles) are available for cleft patients and families should use the one which works best for their child [

4,

5].

Presurgical infant orthopedics (PSIO) implies different techniques which facilitates the surgical treatment of children with clefts. [

1,

2,

5,

12,

13,

14]. The external taping is the simplest technique for presurgical molding used in combination with dental plate [

1,

5,

12,

13,

14]. Objectives of presurgical nasal and alveolar molding (PNAM) which (in most cases) is applied during 6 weeks after birth are active molding and repositioning of the nasal cartilages and alveolar processes, and lengthening of the deficient columella [

1,

5,

12,

13]. Presurgical infant orthopedics is classified as passive (by using of alveolar molding plate known as Liu’s and Grayson’s method) and active (which requires a surgical procedure to introduce the device and to remove it - Latham pinned coaxial screw appliance) [

1,

5]. Gingivoperiostoplasty (GPP) is a procedure used for correction of the cleft alveolar segments at the time of cleft lip repair [

1,

2,

5]. If the alveolar segments are appropriately aligned and <2 mm apart, then the infant is candidate for GPP, if this is not a case, then alveolar bone grafting should be performed [

1,

2,

5,

13].

The goal of any operative technique for CL is to restore normal appearance including lip and nasal deformity [

1,

2,

3,

5,

13,

14,

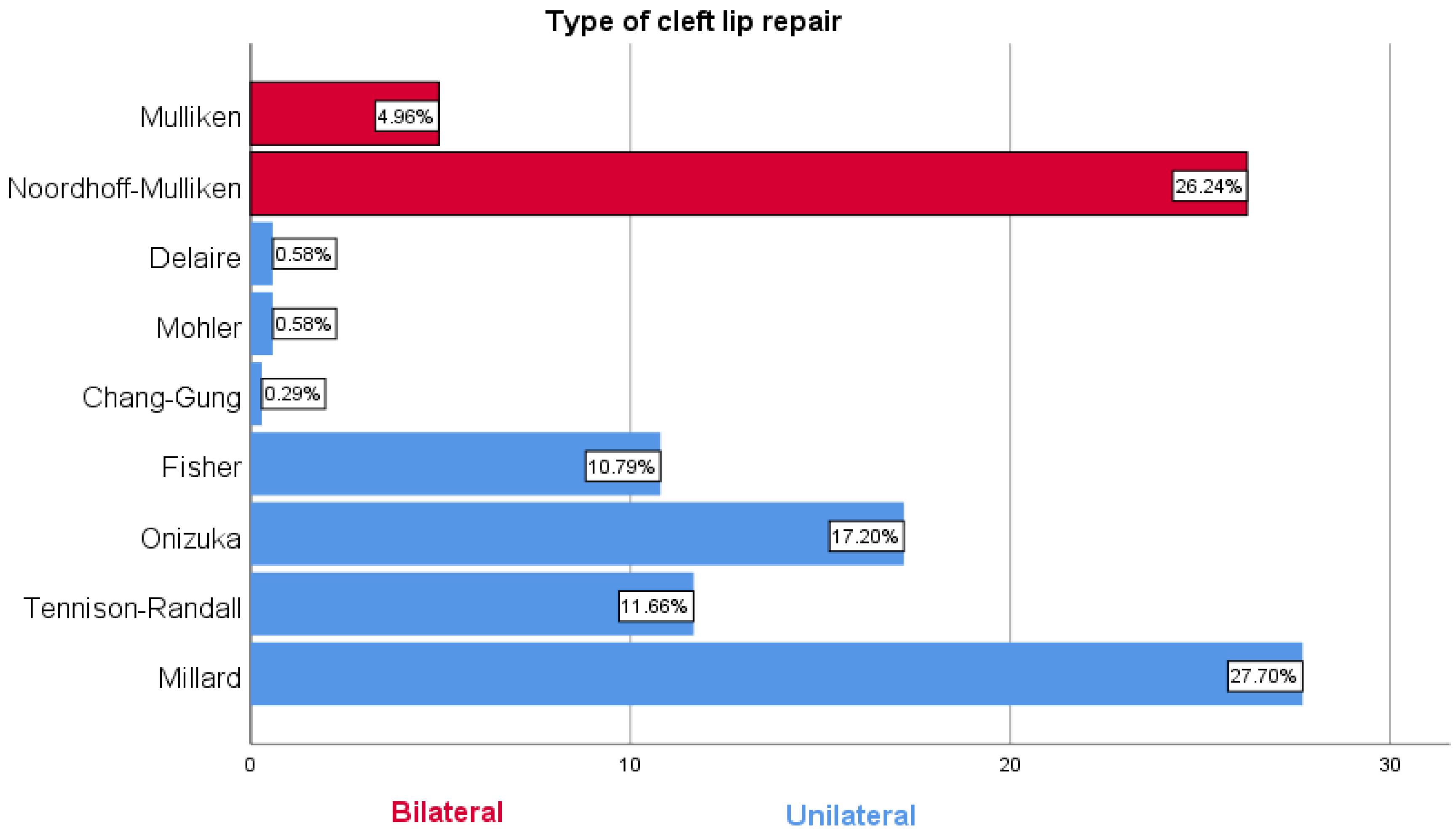

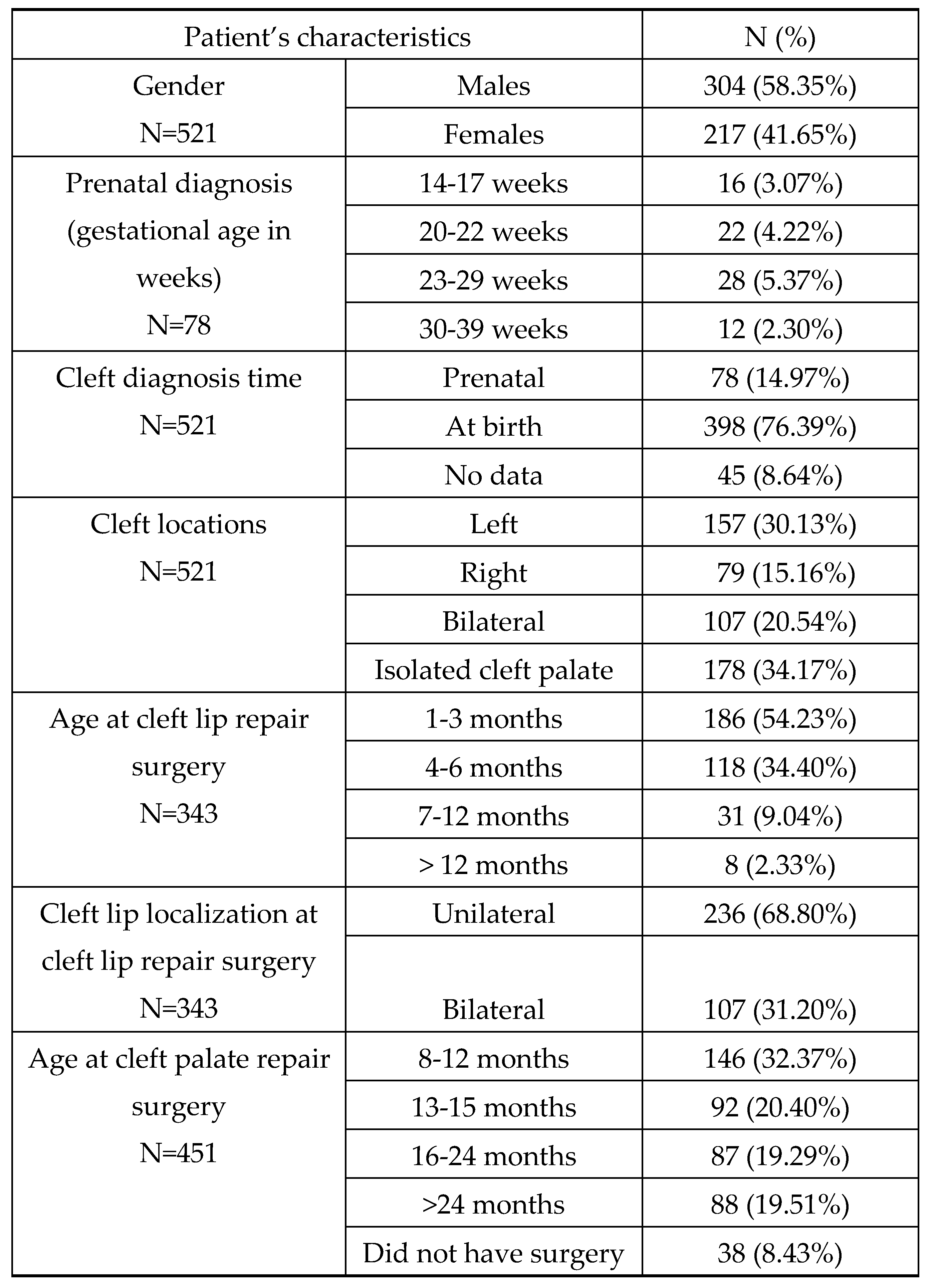

15]. The two most common techniques for unilateral CL repair are straight-line (Tennison) and rotation-advancement (Millard) repairs [

14,

15]. There are several other operative techniques such as: Noordhoff (Chang Gung), Mohler, Fisher etc. [

1,

2,

5,

14,

15]. The CL repair is scheduled when the patient is approximately 3 months of age and it’s performed in general anesthesia [

1,

14]. There are several techniques for bilateral cleft lip and nose repair (Mulliken, Chen-Noordhoff, McComb, Cutting,) with the similar goals of operative techniques as for the unilateral clefts [

1,

3,

5,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Currently two common approaches to the timing of cleft palate repair exists: one-stage repair, and two-stage repair [

1,

2,

6]. According to Woo, 88% of surgeons in the United States use one stage cleft palate repair between 6 and 14 months [

7,

14,

15].

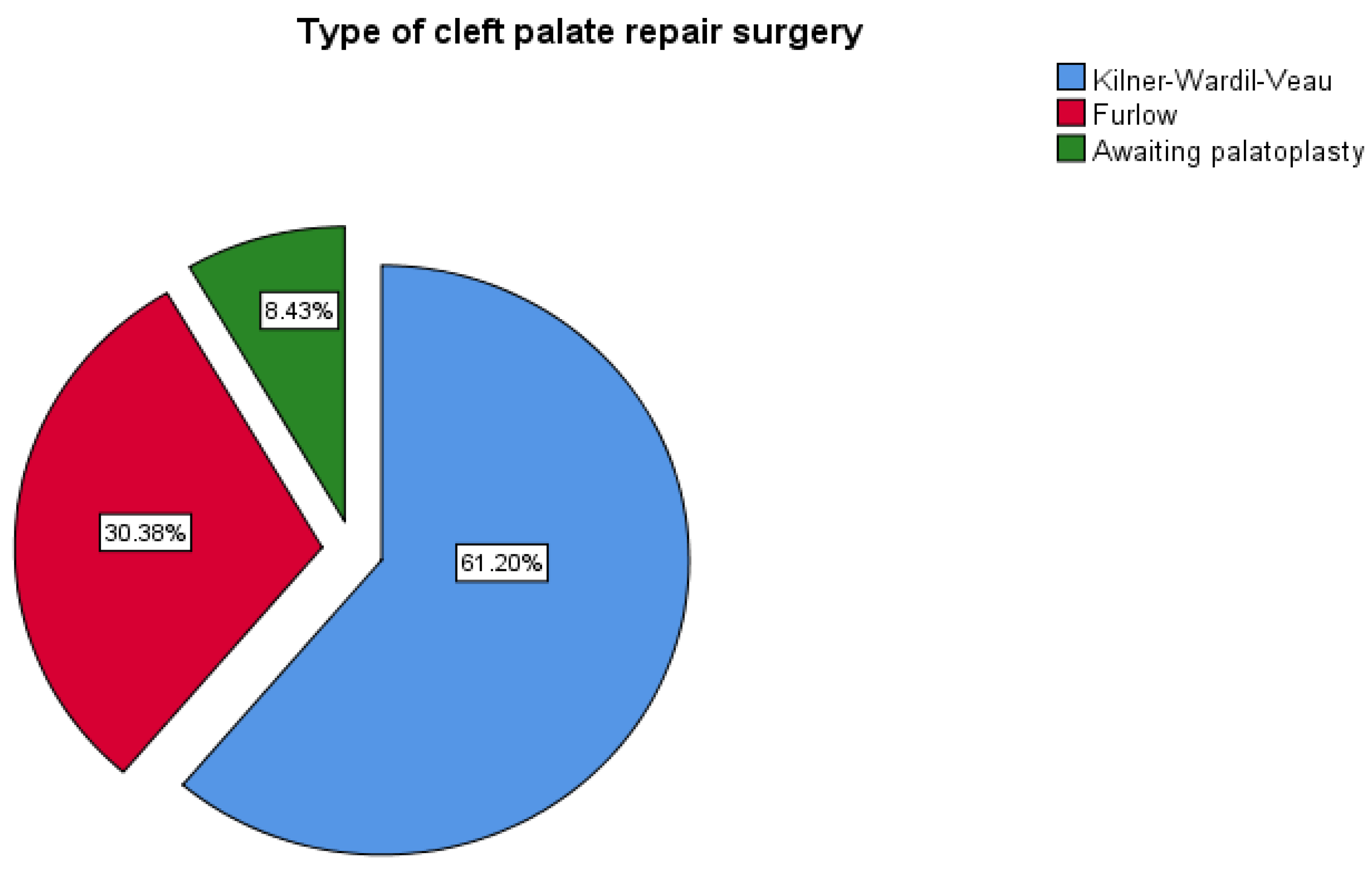

The most common techniques used for hard palate repair are Bardach two-flap palatoplasty, von Langenbeck bipedicle flaps, Veau-Wardill-Kilner pushback technique, with several other techniques such as buccal myomucosal flap or buccal fat pad flaps [

1,

2,

7,

13,

14]. In case of wide clefts vomerine flaps are used for closing nasal mucosa [

7].

For soft palate repair intravelar veloplasty, radical intravelar veloplasty, or Furlow double opposing “Z” plasty are most commonly used techniques [

1,

2,

5,

7,

15]. Sommerlad et al. promote the use of the operating microscope for cleft palate repair [

7,

15].

The primary goal of palatoplasty is normal speech, based on the ability of complete closing of the velopharyngeal sphincter [

2,

5,

13,

14,

15]. Velopharyngeal insufficiency presents the inability of closing the velopharyngeal sphincter and this is presented by hypernasality, nasal emission, and imprecise consonant production [

1,

2,

5,

15]. The diagnosis of VPI is made by subjective and objective means and treatment includes posterior pharyngeal wall augmentation, palatal lengthening, sphincter and pharyngeal flap pharyngoplasty etc. [

2,

5,

15]. Furlow technique can be also used to treat velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI) [

1,

2,

5,

7].

Hearing loss is a well-known complication of CP, and these patients need ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist and audiological surveillance [

1,

2,

5,

13]. Cleft palate closure significantly reduces the prevalence of audiological problems [

13]. Cleft lip and palate include various abnormal dental conditions [

10].

Additional surgery includes previously mentioned bone grafting, pharyngoplasty, fistuloraphy, rhinoplasty, and LeForte osteotomies (middle face retraction) and they are performed in different age of patients [

5,

16,

17]. Secondary deformities mostly depend of the severity of primary defect, effectiveness of orthodontic treatment, and the method of repair and there are several different techniques for treatment of secondary cleft deformities [

16,

17].

1.2. Classification

There are several classification systems of CL/P developed and implemented from the beginning of the last century [

1,

2,

5,

8,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Despite numerous attempts, there is still need for a universal and simple classification which would find clinical application [

8,

18,

30]. Houkes at al. stated that classifying clefts in a clear, easy to understand and concise manner is a key element of cleft care [

30].

Ritchie and Davis suggested the classification of CL/P at 1922 which gained wide acceptance [

2,

18,

20,

22,

25]. They have used the alveolar process as a line of division between lip and palate anomalies [

18].

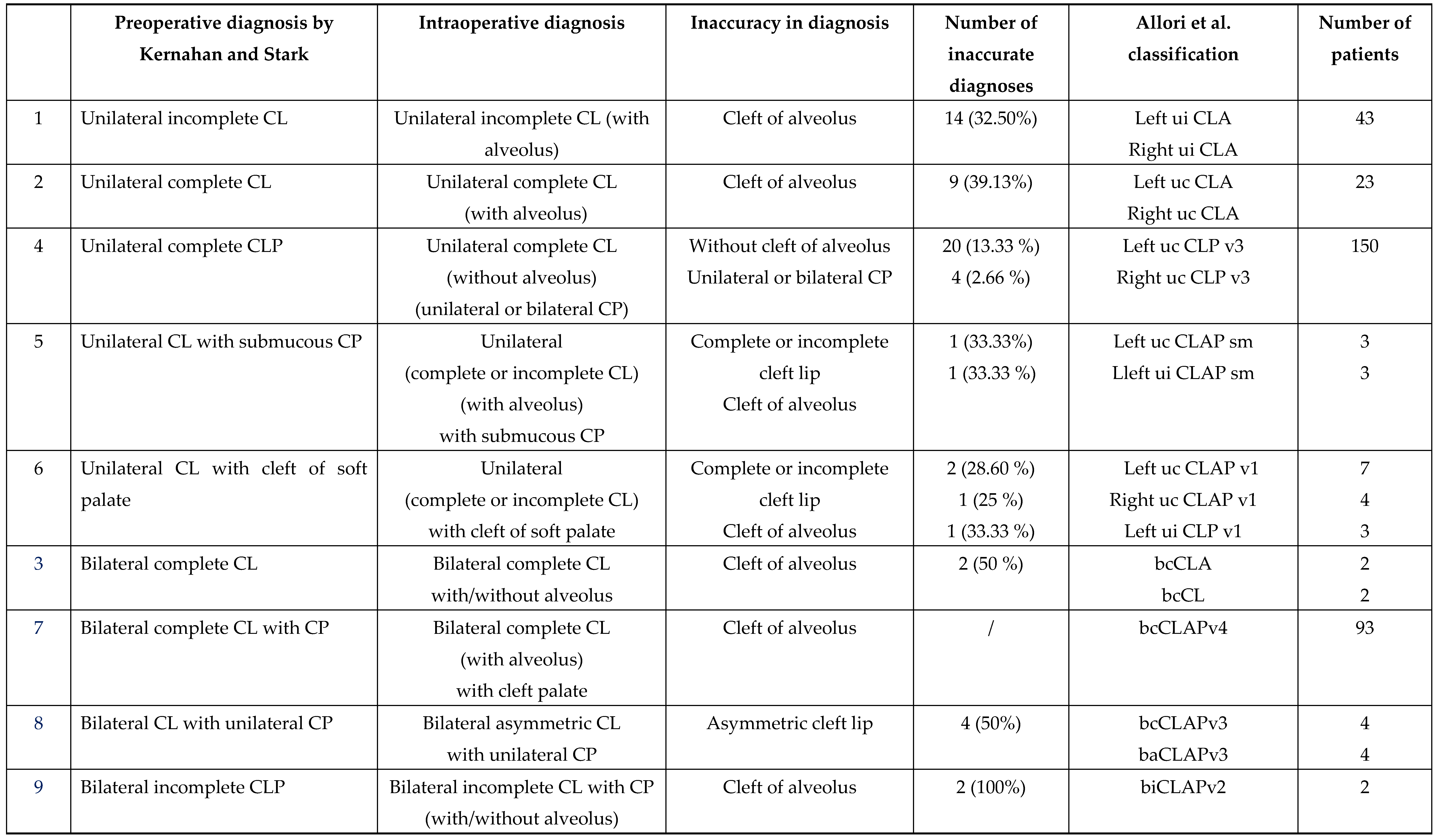

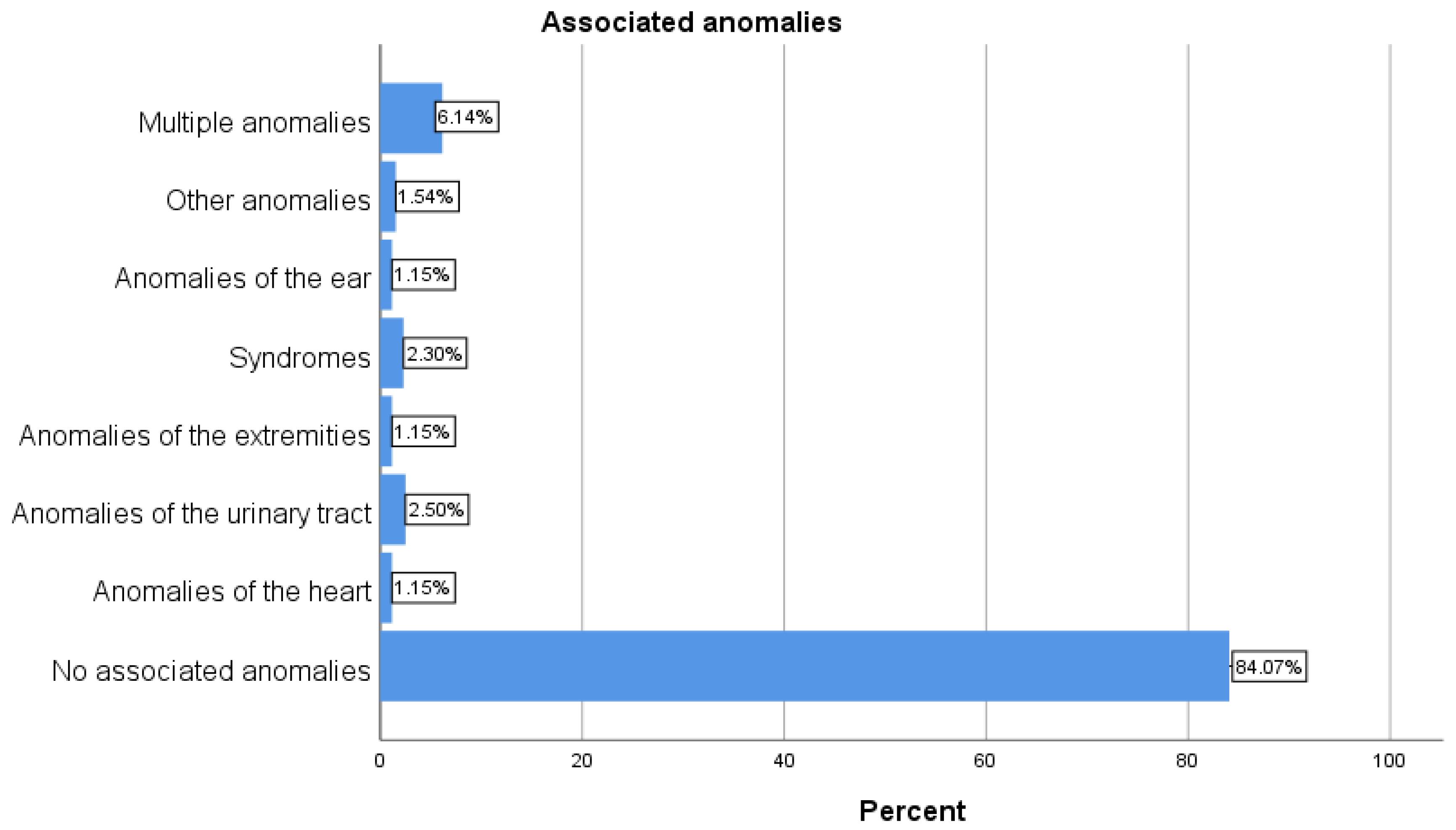

Kernahan and Stark presented new classification for CL/P in 1958 (on embryological basis), and they proposed that instead of alveolus, incisive foramen become dividing point between different groups of clefts including: cleft of primary palate (lip and premaxilla), cleft of secondary palate only, and clefts of primary and secondary palate [

1,

2,

8,

18]. After 15 years Kernahan stated that the size of charts of cleft patients is a problem especially that they don’t show the exact degree of clefts [

18]. At 1973 he proposed a “Y” shaped diagram where the upper limbs represent primary palate and lower limb represent hard and soft palate [

1,

2,

8,

11,

19,

20,

21,

22]. This was followed by several modifications of Kernahan “Y” classification by different authors. Elsahry at 1973 offered modified stripped “Y” classification [

22]. Sandham in 1985 modified Kernahan and Stark classification of CL/P by adding the group of rarer types of facial clefts [

20]. Friedman et al. in 1991 proposed a modification of Kernahan “Y” classification assigning the scale depending on the severity of clefts [

2,

26]. Smith at 1998 revised the Kernahan “Y” classification and proposed the system that allows a compact alphanumeric description of any cleft [

2,

25]. At 2013 Khan et al. revised Smiths modification of Kernahan striped “Y” classification by incorporating different subclasses of submucous cleft palate [

29].

Despite numerous modifications of Kernahan “Y” classification, there was still no classification that would satisfy all the necessary criteria for a universally accepted classification [

22]. Otto Kriens in 1989 proposed a system that used letters to present components and by this system every possible cleft form can be typed [

2,

21]. The acronym LAHSHAL denotes the bilateral anatomy of lip (L), alveolus (A), hard (H) and soft (S) palates [

2,

21,

22]. Capital letters indicate complete clefts, small one’s partial clefts, asterisks (*) noted the minimal clefting, the dot (.) means that anatomic feature is unaffected, and (+) sign can be placed for Simonart band in the L column [

1,

2,

8,

22,

30]. The right side is the left side of the patients and vice versa (like an x-ray formula) [

22]. According to Houkes et al. LAHSHAL could be the most suited universal classification system [

30].

Schwartz et al. in 1993 have reviewed existing classifications presented by Davis and Ritchie, Brophy, Veau, Fogh-Andersen, Pruzanski, Kernahan and Stark Harkins et al., Vilar-Sancho and Kernahan [

1,

2,

23,

30]. They conclude that 63 possible combinations of clefting may occur and by comparing description of the type of cleft by anatomic components and its modification presented by Kernahan, they developed their three-digit numerical system where the three limbs of “Y” present three-digit (RPL) [

23,

26].

Mortier et al. analyzed patients with partial unilateral incomplete clefts and they proposed the rating scheme which permits the comparison of postoperative results with the severity of the cleft [

24,

31]. Ortiz-Posadas et al. proposed a more precise modification of Mortier binary method by assigning a value to each one of the clefts [

2,

26].

According to Liu et al. an ideal system of classification would be easy to understand and to document, with the detailed information of the exact location and the extent of the deformities [

27]. They criticized Kernahan's classification stating that, among other things, it did not adequately describe asymmetric bilateral clefts and that the data from this classification could not be adequately computerized, and also analyzed Smith et al. and Schwartz et al. modification of Kernahan classification. Liu et al. stated that their LAPAL system (L-right lip, A-left alveolus and primary palate, P-secondary palate, A-left alveolus and primary palate, L- left lip, with the extent of cleft deformity presented by Arabic numerals 0 to 4) allows a numerical description of all kinds of clefts [

27].

Koul et al. analyzed following symbolic classifications: striped “Y” classification of Kernahan, RPL system of Schwartz, and the LAHSHAL system of Royal College of Surgeons and criticized them mainly for not defining the extent of the cleft in a particular unit. They stated that their classification of CL/P named “Expression System” that comprises two components: (1) anatomical nomenclature (text) and (2) symbols based on the phrase ‘‘lip and palate’’ is accurate and flexible to record the degree and variations of clefting of the lip and palate [

28].

Singh stated that classification scheme of the American Cleft Palate Association (ACPA) which is more complex compare to Kernahan and Stark classifications represent probably the best variable system based on embryological theory about the development of the face [

31].

At 2017 Allori et al. summarized the experience related to cleft classification systems and according to criteria for an “ideal classification scheme” offered their own classification that includes the laterality and severity of labial defect, description of an alveolar defect and a morphological characterization of the palatal defect, with exclusion of facial clefts.

Authors stated that:

a. Incisive foramen is surgically useful dividing point;

b. Integrity of alveolar process is critical detail;

c. Morphologic features of labial and palatal cleft should be described to degree relevant to treatment planning; and

d. High-level morphological details should be excluded from the classification, and by that complete description of CL/P should include the laterality and severity of the labial defect, acknowledgment of alveolar defect, and a morphological characterization of the palatal defect [

30,

32].

In order to avoid longhand notations authors developed complementary shorthand notation which is strictly structured according to a few rules and definition [

32]. Uppercase letters summarize anatomical involvement (C stands for the word cleft,

L for lip,

A for alveolus, and

P for palate, while lowercase prefix describes of the preforaminal and postforaminal component: the laterality (

u, unilateral;

b, bilateral;

med, median;) and severity (

c, complete;

i, incomplete;

m, lesser form [minor-form, microform, or mini-microform]; and

a, asymmetric (only for bilateral case) [

32]. For unilateral cases the terms

right and

left are not abbreviated. Morphology of the cleft palate is described as follows:

bu (bifid uvula),

sm (submucous cleft palate with/without bifid uvula,

v1,

v2,

v3,

v4 according to Veau classification of cleft palate The plus sign (+) means “and”, that is combination of two features, the plus or minus sign (±) mean “with/without” and the virgule / mean and/or [

32]. The author suggested that initial encounter describe the CL/P using longhand structured form and all the notes at subsequent encounters may simply reference the shorthand notation.

The primary aim of this study is to perform a review of the accuracy of the preoperative diagnoses for the patients with CL/P. Furthermore, we aimed to point out errors that occur when applying standard classifications, and to demonstrate the simplicity and comprehensiveness of the Allori et al. classification.