1. Introduction

The risk of developing ovarian cancer is low, approximately 1%. Nevertheless, only 20% of the patients are diagnosed at an early stage [

1]. The prognosis of early stage disease is significantly better from advanced stages with a 5-year survival around 90% [

2]. The importance of comprehensive staging in early ovarian cancer was described by Young et al. in 1983 [

3] and was confirmed by later studies [

4,

5,

6], where upstaging of the disease ranged from 30% to 50% of the cases. The high prognostic value of a complete staging procedure on patients’ outcomes has been verified by several studies [

7,

8,

9]. Furthermore, data about recurrence in early stage ovarian cancer revealed that 25 – 28% of these patients will experience a relapse [

10]. Concerning the site of first recurrence, the majority of them will occur at the peritoneum suggesting that more efforts should be directed towards an extensive and radical surgery at the peritoneum. [

11]. However, the recommendation for peritoneal staging, when no macroscopic disease is present, remains to perform blind biopsies of the vesicouterine pouch, the pouch of Douglas, the paracolic gutters and the hemidiaphragms [

12,

13].

Douglasectomy is defined as the removal of the entire peritoneum of the pouch of Douglas. This procedure is not routinely performed in gynecologic surgery, since it requires recognition and dissection of vital structures in the pelvis: ureters, hypogastric plexus, rectosigmoid. Intraoperative injury of the abovementioned structures can lead to increased morbidity and mortality. Douglasectomy is often used for benign conditions in gynecology, such as deeply infiltrative endometriosis of the rectovaginal septum [

14] or painful uterine retroversion [

15], with excellent results concerning safety and quality of life. Moreover, the en-block removal of the whole pelvic peritoneum, including the pouch of Douglas, in order to achieve complete removal of the tumor burden in cases of locally advanced ovarian cancer was firstly described by Hudson in 1968 [

16].

On the other hand, there are no reports in the literature for role of douglasectomy in presumed FIGO stage I ovarian cancer. Thus, leaving simple hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy as the standard of care in the pelvis. The question arises about the implementation of douglasectomy instead of random blind biopsies from the normal appearing pelvis. The rationale behind this is that isolated microscopic cancer cells might disseminate from the ovaries and implant to their neighboring pelvic peritoneum. So, the en-block removal of the peritoneum of the pouch of Douglas with the uterus is the goal. This type of procedure was step-by-step analyzed [

17] for the treatment of locally advanced disease: bilateral retroperitoneal exposure, development of the paravesical and pararectal spaces, uterolysis, completion of the typical steps of a simple hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, round colpotomy from anterior to posterior and retrograde dissection of the rectovaginal septum until the complete removal of the peritoneum of the pouch of Douglas. The aim of this study is to investigate the safety and feasibility of douglasectomy and its impact on the survival rates of patients with early ovarian cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Characteristics

Retrospective analysis of women with newly diagnosed early ovarian cancer, who underwent surgery in the 1st Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, AUTh, “Papageorgiou” General Hospital, from 1 January 2012 until 31 December 2022. After careful review of the operative and the final pathology report patients with disease confined to the ovaries with or without positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes were included in the study. So, the population consists of patients with presumed FIGO stage I ovarian cancer, because of the inclusion of those that were final upstaged to FIGO Stage IIIA1 due to microscopically lymph node involvement. In these patients the disease was macroscopically confined to the ovaries with no visible bulky retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, but the final pathology report revealed positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

The definitive diagnosis of malignancy was established in the final pathology report, while the suspicion of ovarian cancer was set by imaging (MRI scan, vaginal ultrasound with IOTA score) and was confirmed by the intraoperative frozen section biopsy of the adnexal mass. The total number of patients retrieved in this period was 110. A written approval was received from the Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Patients

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Prior surgery in the pelvis

Recurrent ovarian cancer.

Missing important registry data.

As a result of the above-mentioned criteria, 17 out of the 110 women with early ovarian cancer were excluded due to non-epithelial histopathological diagnosis or as a recurrence of early ovarian cancer. Moreover, 3 women were excluded, because they were missing important registry data and 2 due to prior surgery in the pouch of Douglas. Hence, finally 88 women with presumed FIGO stage I ovarian cancer were identified as eligible for further analysis, with no duplicate data and important missing values. Patients were divided into 2 groups: Group A that underwent en-block hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and douglasectomy, Group B (control) that underwent simple hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and random pelvic biopsies. Patients in both groups underwent also staging surgery with infracolic omentectomy, pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy and peritoneal biopsies from the vesicouterine pouch, the paracolic gutters and the hemidiaphragms.

2.3. Data Collection

Data was collected during a period of one month. Our Gynecological – Oncology Unit has an online registry with all the relevant data of the patient’s medical records. In order to avoid inconsistencies among different dates of data collection, a uniform data collection sheet (excel file) was used, during the retrospective mining of the patient’s medical records. The data sheet included the following information:

-

Patient’s identifiers:

- ◦

Name

- ◦

Hospital identification number

Patient’s age

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)

FIGO stage

Tumor marker CA-125 preoperative value

Histopathology

Intraoperative blood loss

Surgery duration

Type of surgery: douglasectomy or random peritoneal biopsies

Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission

Clavien-Dindo classification for post-operative complications

Hospital stay

-

Time related data:

- ◦

Date of surgery

- ◦

Date of recurrence

- ◦

Date of last follow-up or death

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We analyzed data using R statistical software (R Project for Statistical Computing), version 4.3.0. For descriptive statistics of qualitative variables, the frequency distribution procedure was run with calculation of the number of cases and percentages. Test of normality was conducted using Shapiro–Wilk or Kolmogorov– Smirnov tests. On the other hand, for descriptive statistics of quantitative variables, the mean, median, range, and standard deviation were used to describe central tendency and dispersion. Disease-free (DFS) and overall survival (OS) analyses were performed using the Kaplan – Meier curves and groups were compared using the log-rank test. Disease-free survival was defined as the time interval between date of surgery and date of first recurrence, while overall survival as the time interval from diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. All reported p-values were two-tailed at a 5% significance level.

3. Results

This retrospective cohort study included 110 women with early ovarian cancer that were treated in the Gynecological – Oncology Unit, 1st Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, “Papageorgiou” General Hospital. After screening of the patients based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 88 patients were eligible for further analysis in this study.

The population of the study was divided into two groups based on the removal of the peritoneum of the pouch of Douglas. So, Group A included 27 (30.7%) patients that underwent douglasectomy and Group B included 61 (69.3%) patients with random pelvic biopsies. Patients’ characteristics of the two groups are outlined in

Table 1. The two groups were similar concerning age, BMI and comorbidities, which were measured with Charlson Comorbidity Index. Our patients were approximately 55 years old, with a median BMI of 28 (overweighted) and with mild comorbidities. Moreover, no difference was observed in terms of the histopathological subtypes, with the majority of the patients suffering from high grade serous neoplasms. Also, there was no significant difference in the intraoperative blood loss (300cc) and the need for ICU admission after surgery. On the other hand, patients that underwent en-block hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and douglasectomy had a significantly higher pre-operative CA-125 (Group A: 192.5 vs. Group B: 48.5) (p=0.018) and a significantly longer surgery duration (Group A: 270 min vs. Group B: 180 min) (p <0.01) and hospital stay (Group A: 8 days vs. Group B: 7 days) (p <0.01). Furthermore, patients that underwent douglasectomy had a significantly higher rate of postoperative complications, which was measured with Clavien-Dindo classification (Group A: 17.3 vs. Group B: 15) (p=0.033), but with no grade 3 complications.

Analyzing the distribution of the FIGO staging system of the study’s population the majority of the patients were FIGO stage IA (n=74, 84.1%) and only a fraction of patients (n=14, 15.9%) were upstaged to FIGO stage IIIA

1. There was no statistically significant difference in the FIGO sub-stages between the two groups and specifically FIGO stage IIIA

1 patients were evenly divided in Group A and B (7 patients each). The aforementioned data are analyzed in

Table 2.

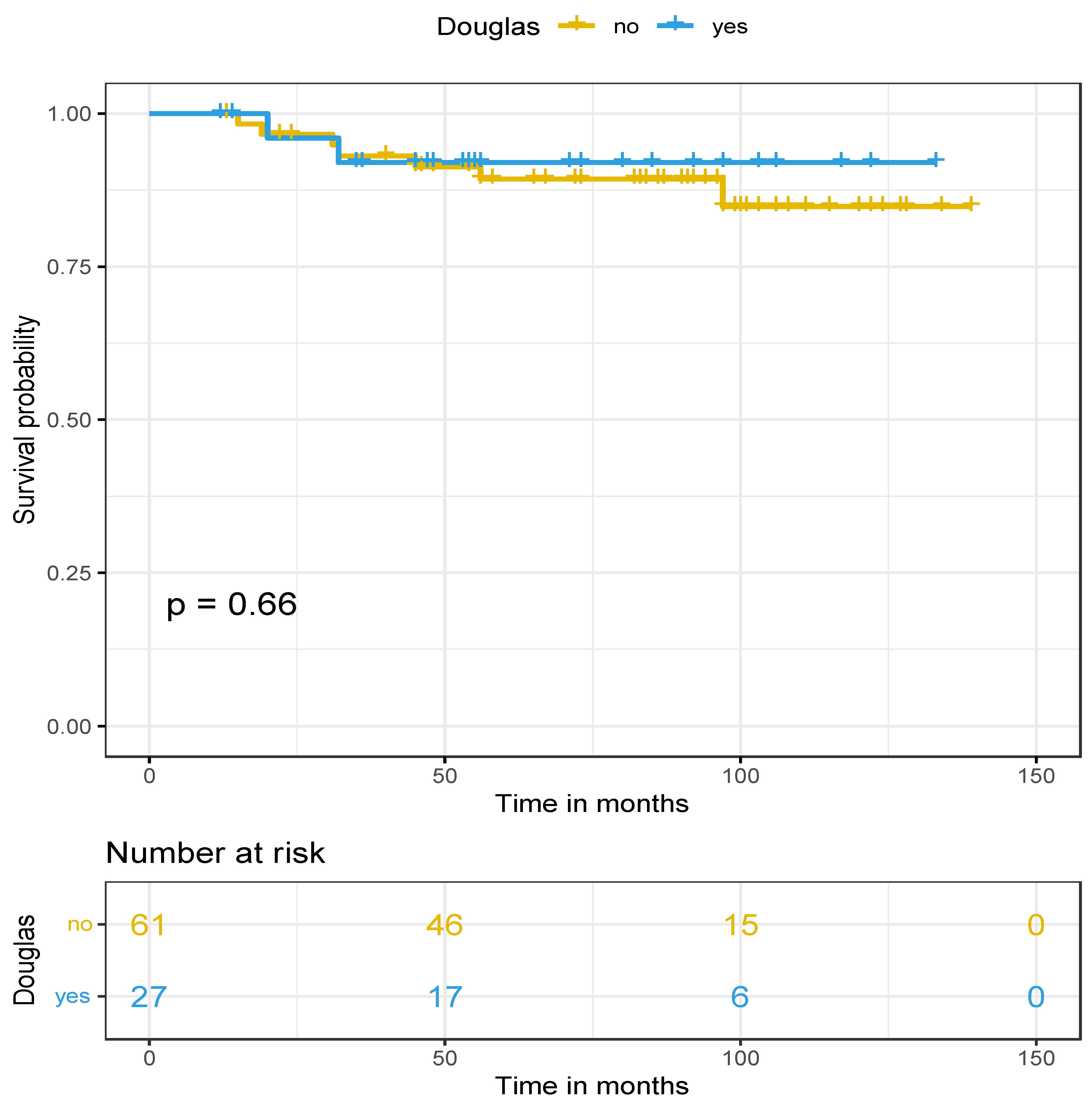

The median follow-up of the cohort was 83.4 months with an IQR: 49-100.7. Regarding survival rates, there was a significant difference in disease-free survival (p=0.033) in favor of the douglasectomy group, with the median DFS in Group A at 47 months and at Group B at 19 months. Concerning the first recurrence site in both groups, no relapse was found in the pelvis and especially in the pouch of douglas in the douglasectomy group (Group A). However, 4 out of the 7 cases of recurrence concerned retroperitoneal lymph nodes and all patients were initially FIGO stage IIIA

1. In contrary, in 4 cases out of 7 in the random pelvic biopsies group (Group B) a nodule in the pelvic peritoneum was presented as the first recurrence site and only 2 cases of a retroperitoneal lymph node relapse, who also were initially FIGO stage IIIA

1. Last but not least, no difference was observed in the overall survival (p=0.66) between the two groups (median OS >141 months). Nevertheless, a trend for a better overall survival was observed in favor of the douglasectomy group, because 10-year OS was approximately 92% for Group A and 85% for Group B. Survival data are presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 for DFS and OS, respectively.

4. Discussion

The primary objective of our study was binary. We investigated the safety and feasibility of douglasectomy in presumed FIGO stage I and its impact on disease-free and overall survival. The rationale for this out-of-the-box procedure is that epithelial ovarian cancer tumor cells passively exfoliate from the primary site to the adjacent peritoneal cavity, which is the pouch of Douglas. We performed a retrospective analysis of the operative and final pathology report from all consecutive patients with early ovarian cancer and selected those with FIGO stage I and IIIA1. Then, we divided the population of the study into two groups based on the removal of the whole peritoneum of the pouch of Douglas en-block with the uterus or not: Group A with douglasectomy and Group B with random pelvic biopsies.

Eighty-eight patients were finally included in the study. From them, only a small proportion (n=15, 15.9%) was upstaged at the final pathology report to FIGO stage IIIA1. Group A included 27 (30.7%) and Group B 61 (69.3%) patients, respectively. Even though the population in the two groups was not balanced in terms of numbers, they had similar demographic and disease characteristics (age, BMI, comorbidities, histology, FIGO staging) therefore minimizing possible selection bias. Furthermore, the was no difference between the two groups for the intraoperative blood loss and the need for ICU admission after surgery, showing the douglasectomy, in the hands of a well-trained gynecologist-oncologists with good knowledge of the anatomical landmarks of the pelvis, is a safe and feasible procedure. On the other hand, there was a significant difference between the two groups concerning pre-operative CA-125 values, surgery duration, post-operative complications and hospital stay. Patients that underwent douglasectomy had longer surgery duration, by approximately 90 minutes and longer hospital stay, by one day. This could be explained by the fact that in order to perform a douglasectomy, careful recognition and dissection of vital structures (ureters, hypogastric plexus, rectosigmoid, etc.) is needed. The rate of post-operative complications was higher at the douglasectomy group. However, no grade 3 complication was documented, a fact that empowers the idea that douglasectomy is a safe and feasible procedure.

Investigating the impact of douglasectomy on the survival rates, a long follow-up period was crucial in order to extract safe and robust results. A significant higher DFS in favor of the douglasectomy group was found (medina DFS in Group A: 47 months vs. in Group B: 19 months). Specifically, when looking at the first recurrence site, no relapse in the pelvis (especially the pouch of Douglas) occurred at the douglasectomy group (Group A), while four cases of peritoneal recurrence presented as nodule in the pouch of Douglas at the control group with random pelvic biopsies only (Group B). These promising data highlight the possible important role of douglasectomy in limiting peritoneal recurrences and improving local disease control. In contrast, no difference was observed in OS between the two groups, even though a trend for a better overall survival in favor of the douglasectomy group was observed after 10 years in follow-up.

To our best knowledge this is the only study in the literature that investigates the role of douglasectomy in early ovarian cancer. Recent studies [

18,

19,

20] focusing on the development of peritoneal carcinomatosis highlight the role of the adjacent peritoneum near the primary tumor site. The idea is based on the “seed and soil” theory that was first described in 1989 form Paget [

21,

22], where the “seeds” are the peeled epithelial cancer cells and the peritoneum the “soil”. The first two steps of peritoneal carcinomatosis are the detachment of epithelial ovarian cancer cells from the primary tumor into the pelvic peritoneum and the dissemination of these cells in the peritoneal cavity with the peritoneal fluid between the visceral and parietal peritoneum. Gravity, respiratory and bowel movements create an intra-abdominal flow that transfers the peritoneal fluid in a repetitive pattern from the lower to the upper abdomen [

23]. So, the removal of the whole peritoneum of the pouch of Douglas can stop this process at each initial phase, preventing future peritoneal carcinomatosis.

A retrospective study [

11] investigating the patterns of recurrence in ovarian cancer, included some (n=13, 18%) FIGO stage I patients. The sites of first recurrence, 6 in total, were all in the peritoneum. This finding shows the important role of the peritoneum in tumor dissemination. Moreover, another retrospective cohort study [

6], where FIGO stage IA and IIIA patients (n=35) were reoperated after a median time period of approximately 2 months, with a range almost up to 12 months. The authors found that 12 (34%) patients had metastases to the pelvic peritoneum, when in the primary surgery no evidence of disease was described in that anatomical area.

This is the first study in the literature that investigates the role of douglasectomy in the surgical treatment of early ovarian cancer. All the required parameters were collected from an online system, therefore minimizing the percentage of missing important data. It is of high importance to state that the dataset, on which this study was conducted, comes from an ESGO certified center for Advanced Ovarian Cancer Surgery for over a decade, thus ensuring the high-quality of the data. Nevertheless, the main limitation of our study is the low number of the population, especially at the douglasectomy group, included in the final analysis and its retrospective nature.

The results of our study could have a huge impact in every-day clinical practice, because douglasectomy seems to improve DFS in early ovarian cancer patients, while being a safe and feasible procedure. Further prospective studies are imperative to validate these promising results, before douglasectomy is established in the algorithm of early ovarian cancer staging procedure.

5. Conclusions

En-block douglasectomy with the uterus in early ovarian cancer patients seems to be a safe and feasible procedure that has a huge impact in the disease-free survival. The rationale about this out-of-the-box procedure can be explained by the theory of peritoneal carcinomatosis development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Z. and D.T.; methodology, P.T.; software, D.Z.; validation, M.T., E.T. and D.T.; formal analysis, I.S and T.K..; investigation, P.T. and D.Z..; resources, V.T. and D.T.; data curation, K.C. and T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Z. and P.T.; writing—review and editing, D.T.; visualization, G.G.; supervision, D.T., E.T., G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board) of PAPAGEORGIOU General Hospital (Νο. 7241/06/03/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to fact that this was retrospective study and no change in the treatment of the patients was made

Data Availability Statement

In accordance with the journal’s guidelines, the data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author for the reproducibility of this study if such is requested.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ovarian Cancer — Cancer Stat Facts Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html.

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.C.; Decker, D.G.; Wharton, J.T.; Piver, M.S.; Sindelar, W.F.; Edwards, B.K.; Smith, J.P. Staging Laparotomy in Early Ovarian Cancer. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1983, 250, 3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, E.A.; Barakat, R.R.; Curtin, J.P.; Brown, C.L.; Jones, W.B.; Hoskins, W.J. Laparotomy to complete staging of presumed early ovarian cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 87, 737–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soper, J.T.; Johnson, P.; Johnson, V.; Berchuck, A.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comprehensive restaging laparotomy in women with apparent early ovarian carcinoma. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992, 80, 949–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grabowski, J.P.; Harter, P.; Buhrmann, C.; Lorenz, D.; Hils, R.; Kommoss, S.; Traut, A.; du Bois, A. Re-operation outcome in patients referred to a gynecologic oncology center with presumed ovarian cancer FIGO I-IIIA after sub-standard initial surgery. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 21, 31–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimbos, J.B.; Vergote, I.; Bolis, G.; Vermorken, J.B.; Mangioni, C.; Madronal, C.; Franchi, M.; Tateo, S.; Zanetta, G.; Scarfone, G.; et al. Impact of Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Surgical Staging in Early-Stage Ovarian Carcinoma: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Adjuvant ChemoTherapy in Ovarian Neoplasm Trial. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bristow, R.E.; Santillan, A.; Diaz-Montes, T.P.; Gardner, G.J.; Giuntoli, R.L.; Meisner, B.C.; Frick, K.D.; Armstrong, D.K. Centralization of care for patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Cancer 2007, 109, 1513–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, M.J.A.; Kos, H.E.; Willemse, P.H.B.; Aalders, J.G.; de Vries, E.G.E.; Schaapveld, M.; Otter, R.; van der Zee, A.G.J. Surgery by consultant gynecologic oncologists improves survival in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Cancer 2006, 106, 589–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, M.D.; O’malley, D.M.; Haight, P.J.; Senter, L.; Wagner, V.; Bixel, K.L.; Cohn, D.E.; Copeland, L.J.; Cosgrove, C.M.; Mclaughlin, E.M.; et al. Recurrence rate in early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer: Is there a role for upfront maintenance with PARP inhibitors in stages I and II? Gynecol. Oncol. Reports 2023, 46, 2352–5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amate, P.; Huchon, C.; Dessapt, A.L.; Bensaid, C.; Medioni, J.; Le Frère Belda, M.-A.; Bats, A.-S.; Lécuru, F.R. Ovarian cancer: sites of recurrence. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2013, 23, 1590–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.K.; Alvarez, R.D.; Backes, F.J.; Bakkum-Gamez, J.N.; Barroilhet, L.; Behbakht, K.; Berchuck, A.; Chen, L.-M.; Chitiyo, V.C.; Cristea, M.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Ovarian Cancer, Version 3.2022. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2022, 20, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Querleu, D.; Planchamp, F.; Chiva, L.; Fotopoulou, C.; Barton, D.; Cibula, D.; Aletti, G.; Carinelli, S.; Creutzberg, C.; Davidson, B.; et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO) Guidelines for Ovarian Cancer Surgery. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 1534–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, D.G.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, Y.H.; Chong, G.O.; Cho, Y.L.; Lee, Y.S. Safety and effect on quality of life of laparoscopic Douglasectomy with radical excision for deeply infiltrating endometriosis in the cul-de-sac. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2014, 24, 165–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Theobald, P.; Barjot, P.; Levy, G. Laparoscopic douglasectomy in the treatment of painful uterine retroversion. Surg. Endosc. 1997, 11, 639–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, C.N. A radical operation for fixed ovarian tumours. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Br. Commonw. 1968, 75, 1155–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeles, M.A.; Martínez-Gómez, C.; Martinez, A.; Ferron, G. En bloc pelvic resection for ovarian carcinomatosis: Hudson procedure in 10 steps. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 153, 209–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Baal, J.O.A.M.; van Noorden, C.J.F.; Nieuwland, R.; Van de Vijver, K.K.; Sturk, A.; van Driel, W.J.; Kenter, G.G.; Lok, C.A.R. Development of Peritoneal Carcinomatosis in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: A Review. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2018, 66, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, T.; Murphy, B.; Zhang, N. Intraperitoneal metastasis of ovarian cancer: new insights on resident macrophages in the peritoneal cavity. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1104694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Chen, Y. Tumor microenvironment in ovarian cancer peritoneal metastasis. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidler, I.J. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the “seed and soil” hypothesis revisited. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 453–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paget, S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Lancet 1889, 133, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raptopoulos, V.; Gourtsoyiannis, N. Peritoneal carcinomatosis. Eur. Radiol. 2001, 11, 2195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).