Submitted:

23 August 2024

Posted:

26 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Jordan's Pledge to Sustainability

3. Amman Urban Law

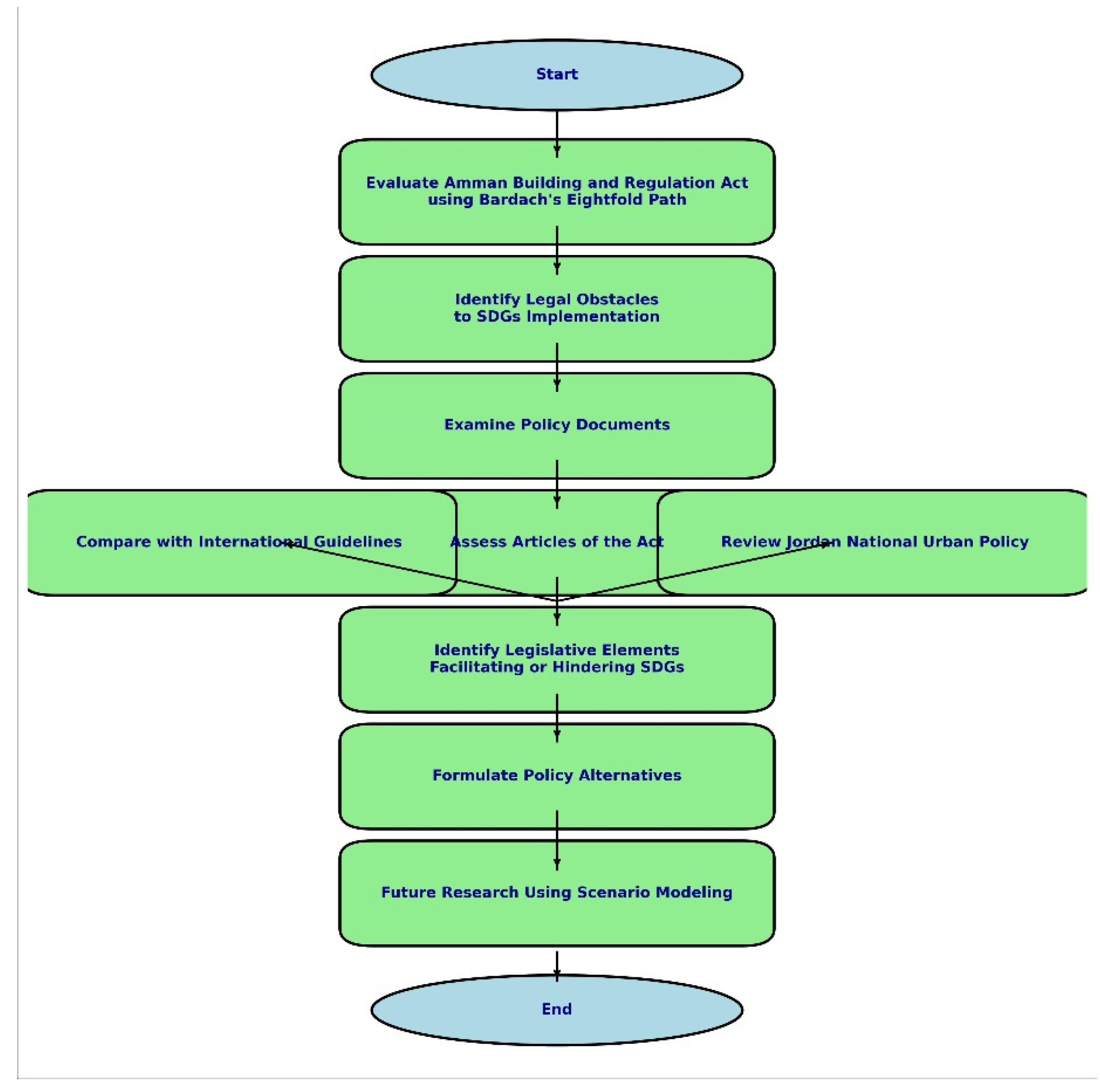

4. Material and Methods

4. Discussion

- Lack of public Inclusion and Empowerment

- Insufficient Advancement of Affordable and Clean Energy Utilization

- Imprudent Use of Natural Resources

- Deficit of Legislative Support for Sustainable Industrialization

- Insufficient Deployment of Green Infrastructure

- 6)

- >6) Underutilization of Sustainable Construction Material Practices

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. (2018). World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved from https://population.un.

- Rahaman, M. A., Kalam, A., & Al-Mamun, M. (2023). Unplanned urbanization and health risks of Dhaka City in Bangladesh: uncovering the associations between urban environment and public health. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1269362.

- Aliyu, A. A. , & Amadu, L. (2017). Urbanization, cities, and health: the challenges to Nigeria–a review. Annals of African medicine, 16(4), 149-158.

- Zhang, X. Q. (2016). The trends, promises and challenges of urbanisation in the world. Habitat international, 54, 241-252.

- Swan, A. (2010). How increased urbanisation has induced flooding problems in the UK: A lesson for African cities?. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 35(13-14), 643-647.

- Godfrey, R., & Julien, M. (2005). Urbanisation and health. Clinical Medicine, 5(2), 137. [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, M. (2003, January). Urbanization, urban environment and land use: challenges and opportunities. In Asia-Pacific Forum for Environment and Development, Expert Meeting (Vol. 23, pp. 1–14).

- Tsalis, T. A., Malamateniou, K. E., Koulouriotis, D., & Nikolaou, I. E. (2020). New challenges for corporate sustainability reporting: United Nations' 2030 Agenda for sustainable development and the sustainable development goals. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(4), 1617-1629.

- Boluk, K. A., Cavaliere, C. T., & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2019). A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism.

- Bebbington, J., & Unerman, J. (2018). Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: an enabling role for accounting research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(1), 2-24.

- Biermann, F., Kanie, N., & Kim, R. E. (2017). Global governance by goal-setting: the novel approach of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 26, 26-31.

- Di Baldassarre, G., Sivapalan, M., Rusca, M., Cudennec, C., Garcia, M., Kreibich, H.,... & Blöschl, G. (2019). Sociohydrology: scientific challenges in addressing the sustainable development goals. Water Resources Research, 55(8), 6327-6355.

- Morton, S., Pencheon, D., & Bickler, G. (2019). The sustainable development goals provide an important framework for addressing dangerous climate change and achieving wider public health benefits. Public Health, 174, 65-68. [CrossRef]

- Raub, S. P., & Martin-Rios, C. (2019). “Think sustainable, act local”–a stakeholder-filter-model for translating SDGs into sustainability initiatives with local impact. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(6), 2428-2447.

- Maher, R., Maher, M., Mann, S., & McAlpine, C. A. (2018). Integrating design thinking with sustainability science: a Research through Design approach. Sustainability science, 13, 1565-1587.

- Butcher, S., Acuto, M., & Trundle, A. (2021). Leaving no urban citizens behind: An urban equality framework for deploying the sustainable development goals. One Earth, 4(11), 1548-1556.

- Niyommaneerat, W., Suwanteep, K., & Chavalparit, O. (2023). Sustainability indicators to achieve a circular economy: A case study of renewable energy and plastic waste recycling corporate social responsibility (CSR) projects in Thailand. Journal of Cleaner Production, 391, 136203.

- Schwerhoff, G., & Sy, M. (2017). Financing renewable energy in Africa–Key challenge of the sustainable development goals. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 75, 393-401.

- Nazzal, M. (2005). Economic reform in Jordan: an analysis of structural adjustment and qualified industrial zones. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.554.

- UN News. (2023, October 31). UN calls for global action to turn cities into engines of sustainable development. Retrieved from https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/10/1132767.

- UN-Habitat. (2022). World Cities Report 2022. Retrieved from https://unhabitat.org/wcr2022.

- Zeadat, Z. F. (2023). Strategies toward Greater Youth Participation in Jordan’s Urban Policymaking. Journal of Sustainable Real Estate, 15(1), 2204534.

- Alomari, F., & Khataybeh, A. (2021). Understanding of sustainable development goals: The case for Yarmouk University Science students in Jordan. Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction, 11(2), 43-51.

- Boeren, E., & Field, J. (2019). 4th Global Report on Adult Learning and Education: Leave No One Behind--Participation, Equity and Inclusion. UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning.

- Fukuda-Parr, S., & Smaavik Hegstad, T. (2019). “Leaving no one behind” as a site of contestation and reinterpretation. Journal of Globalization and Development, 9(2), 20180037.

- Winkler, I. T., & Satterthwaite, M. L. (2018). Leaving no one behind? Persistent inequalities in the SDGs. In The Sustainable Development Goals and Human Rights (pp. 51-75). Routledge.

- Breuer, A., & Leininger, J. (2021). Horizontal accountability for SDG implementation: A comparative cross-national analysis of emerging national accountability regimes. Sustainability, 13(13), 7002.

- Bowen, K. J., Cradock-Henry, N. A., Koch, F., Patterson, J., Häyhä, T., Vogt, J., & Barbi, F. (2017). Implementing the “Sustainable Development Goals”: towards addressing three key governance challenges—collective action, trade-offs, and accountability. Current opinion in environmental sustainability, 26, 90-96.

- Donald, K., & Way, S. A. (2016). Accountability for the sustainable development goals: a lost opportunity?. Ethics & International Affairs, 30(2), 201-213.

- Sachs, J. D., Schmidt-Traub, G., Mazzucato, M., Messner, D., Nakicenovic, N., & Rockström, J. (2019). Six transformations to achieve the sustainable development goals. Nature sustainability, 2(9), 805-814.

- Nguyen, T. D. M., Mondal, S. R., & Das, S. (2022). Digital Entrepreunerial Transformation (DET) Powered by New Normal Sustainable Developmental Goals (n-SDGs): Elixir for Growth of Country's Economy. In Sustainable Development and Innovation of Digital Enterprises for Living with COVID-19 (pp. 69-84). Springer Nature Singapore.

- Iyengar, R., Mahal, A. R., Felicia, U. N. I., Aliyu, B., & Karim, A. (2015). Federal policy to local level decision-making: Data driven education planning in Nigeria. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 14(3), 76-93.

- Alnsour, J. (2016). Managing urban growth in the city of Amman, Jordan. Cities, 50, 93-99.

- Jarrar, N., & Jaradat, S. (2022). The de-industrialisation discourse and the loss of modern industrial heritage in the Arab world: Jordan as a case study. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development.

- Al-Dalal'a, J. (2023). Fight or Flight: The Many Ways of Tactical Participation Agency in Amman, Jordan. Repurposing Places, 153.

- Abu Murad, M. S., & Alshyab, N. (2019). Political instability and its impact on economic growth: the case of Jordan. International Journal of Development Issues, 18(3), 366-380.

- Awawdeh, M. M., Abuhadba, R. R., Jamhawi, M. M., Rawashdeh, A. I., Jawarneh, R. N., & Awawdeh, M. M. (2024). Urban expansion in Greater Irbid Municipality, Jordan: the spatial patterns and the driving factors. GeoJournal, 89(2), 43. [CrossRef]

- Doraï, K. (2018). Conflict and migration in the Middle East: Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon. Critical perspectives on migration in the twenty-first century, 113-126.

- Abu Hajar, H. A., Al-Qaraleh, L. A., Moqbel, S. Y., & Alhawarat, A. M. (2021). Prospects of sustainable waste management in developing countries: A case study from Jordan. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 193, 1-14.

- Abdeljawad, N., & Nagy, I. (2023). Thirty years of urban expansion in Amman city: urban sprawl drivers, environmental impact and its implications on sustainable urban development: A review Article. Res Militaris, 13(1), 1230-1250.

- Abdeljawad, N., Adedokun, V., & Nagy, I. (2023). Environmental Impacts Of Urban Sprawl Using Remote Sensing Indices: A Case Study Of Amman City–The Capital Of Jordan. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 46(1), 304-314.

- Abdeljawad, N., & Nagy, I. (2023). Thirty years of urban expansion in Amman city: urban sprawl drivers, environmental impact and its implications on sustainable urban development: A review Article. Res Militaris, 13(1), 1230-1250.

- Steele, W., & Rickards, L. (2022). Sustainable Development Goals and Urban Policy Innovation. In: Brears, R.C. (eds) The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Futures. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Ali, H. H., & Al Nsairat, S. F. (2009). Developing a green building assessment tool for developing countries–Case of Jordan. Building and environment, 44(5), 1053-1064.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Country cooperation strategy for WHO and Jordan 2021–2025.

- Dombrowsky, I.(2022). Implementing the 2030 agenda under resource scarcity: The case of WEF nexus governance in azraq/Jordan. In Governing the Interlinkages between the SDGs (pp. 124-139). Routledge.

- Alomari, F., & Khataybeh, A. (2021). Understanding of sustainable development goals: The case for Yarmouk University Science students in Jordan. Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction, 11(2), 43-51. [CrossRef]

- Anselmi, D., D’Adamo, I., Gastaldi, M., & Lombardi, G. V. (2023). A comparison of economic, environmental and social performance of European countries: a sustainable development goal index. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1-25.

- Bani Salameh, M. T., & Aldabbas, K. M. (2023). Electoral districts’ distribution in Jordan: Political geographical analysis. Asian Journal of Comparative Politics, 20578911231173599.

- Cervigni, R., & Naber, H. (2010). Achieving sustainable development in Jordan: country environmental analysis.

- Badrakhan, S. S. E., Mbaydeen, M. A., & Ogilat, O. (2022). The role private universities play in achieving academic, research, political, and economic sustainability in light of national strategy “Jordan's vision 2025” from the perspective of academicians. Sustainable Futures, 4, 100080.

- Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation. (2015). Jordan 2025: A National Vision and Strategy. Retrieved from https://www.mop.gov.jo/DetailsPage/Strategies (Accessed: 22 July 2024).

- Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation. (2021). Jordan's Progress on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Retrieved from https://mop.gov.jo/DetailsPage/SDGs (Accessed: 22 July 2024).

- United Nations. (2017). Jordan's Voluntary National Review 2017 on the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Retrieved July 21, 2024, from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/16289Jordan.pdf.

- Ababsa, M. (2019). Jordan National Urban Policy. Diagnostic Report (Doctoral dissertation, Ifpo-Institut français du Proche-Orient).

- Hajar, H. A. A., Tweissi, A., Hajar, Y. A. A., Al-Weshah, R., Shatanawi, K. M., Imam, R., ... & Hajer, M. A. A. (2020). Assessment of the municipal solid waste management sector development in Jordan towards green growth by sustainability window analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120539.

- Abu Hajar, H. A., Al-Qaraleh, L. A., Moqbel, S. Y., & Alhawarat, A. M. (2021). Prospects of sustainable waste management in developing countries: A case study from Jordan. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 193, 1-14.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), and Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments. Roadmap for Localizing the SDGs. United Nations, 2016. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/commitments/818_11195_commitment_ROADMAP%20LOCALIZING%20SDGS.pdf.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Donors' Mapping Report. 2018. Available at: https://www.undp.org/jordan/publications/donors-mapping-report.

- Qahwaji, Y. "Development Priorities in Jordan: Who Decides on What?" WANA Institute. 2017. Available at: https://wanainstitute.org/en/blog/development-priorities-jordan-who-decides-what.

- Jawarneh, R. N. (2021). Modeling past, present, and future urban growth impacts on primary agricultural land in Greater Irbid Municipality, Jordan using SLEUTH (1972–2050). ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 10(4), 212.

- Keswani, M. (2021). Exploring an integrated pathway for sustainable urban development of refugee camp cities and informal settlements. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, 253, 37-50.

- Klassert, C., Gawel, E., Sigel, K., & Klauer, B. (2018). Sustainable transformation of urban water infrastructure in Amman, Jordan–meeting residential water demand in the face of deficient public supply and alternative private water markets. Urban Transformations: Sustainable Urban Development through Resource Efficiency, Quality of Life and Resilience, 93-115.

- Alnsour, M. A. (2024). An Integrated Goal Programming Model Applied for Planning a National Policy of Sustainable Development: A Case of Jordan. Process Integration and Optimization for Sustainability, 1-27.

- Benito, B., Guillamón, M. D., & Ríos, A. M. (2023). What factors make a municipality more involved in meeting the Sustainable Development Goals? Empirical evidence. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1-24.

- Joint SDG Fund. "Building Blocks to Finance the SDGs in Jordan." Joint SDG Fund, October 30, 2023. Available at: https://jointsdgfund.org/article/building-blocks-finance-sdgs-jordan.

- Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation 2016: “Implementing the 2030 Agenda Through Policy Innovation and Integration”.

- UN-Habitat. Guidelines for Voluntary Local Reviews Volume 1: A Comparative Analysis of Existing VLRs. 2020. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/10/amman_vlr_-english_version-complete-out_for_print-_in_spreads_4.pdf.

- United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG). Guidelines for Voluntary Local Reviews Volume 2: Towards a New Generation of VLRs: Exploring the Local-National Link. 2022. Available at: https://learning.uclg.org/guidelines-for-voluntary-local-reviews.

- United Nations in Jordan. "Sustainable Development Goals | United Nations in Jordan." United Nations, 2024. Available at: https://jordan.un.org/en/sdgs (The United Nations in Jordan).

- Bardach, E., & Patashnik, E. M. (2019). A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving. http://www.gbv.de/dms/sub-hamburg/30636509X.pdf.

- Nazzal, M. (2005). Economic reform in Jordan: an analysis of structural adjustment and qualified industrial zones. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.554.3433&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

- Ndevu, Z., & Muller, K. (2017). A conceptual framework for improving service delivery at local government in South Africa. African Journal of Public Affairs, 9(7), 13-24.

- Mohieldin, M., Wahba, S., Gonzalez-Perez, M. A., & Shehata, M. (2022). The Role of Local and Regional Governments in the SDGs: The Localization Agenda. In Business, Government and the SDGs: The Role of Public-Private Engagement in Building a Sustainable Future (pp. 105-137). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Ben Hassen, T., & EI Bilali, H. (2022). Sustainable Development Goals in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: policy and governance. In SDGs in Africa and the Middle East Region (pp. 1-16). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- AidData. Cutting across contexts: Better evidence to link the SDGs with national planning. AidData, 2022. Available at: https://www.aiddata.org/blog/cutting-across-contexts-better-evidence-to-link-the-sdgs-with-national-planning.

- Arab Renaissance for Democracy and Development (ARDD). Civil Society Challenges in SDG Localization. ARDD, 2022. Available at: https://www.ardd.org/publications/civil-society-challenges-in-sdg-localization.

- Northrop, E., Biru, H., Lima, S., Bouye, M., & Song, R. (2016). Examining the alignment between the intended nationally determined contributions and sustainable development goals. World Resources Institute.

- Ortiz-Moya, F., Tan, Z., & Kataoka, Y. (2023). Follow-Up And Review Of The 2030 Agenda At The Local Level.

- Examining the alignment between the intended nationally determined contributions and sustainable development goals.

- Raub, S. P., & Martin-Rios, C. (2019). “Think sustainable, act local”–a stakeholder-filter-model for translating SDGs into sustainability initiatives with local impact. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(6), 2428-2447.

- Potter, R. B., Darmame, K., Barham, N., & Nortcliff, S. (2009). “Ever-growing Amman”, Jordan: urban expansion, social polarisation and contemporary urban planning issues. Habitat International, 33(1), 81-92.

- Potter, R. B., Darmame, K., Barham, N., Nortcliff, S., & Mannion, A. M. (2007). An introduction to the urban geography of Amman, Jordan. Reading Geographical Papers, 182, 1-29.

- Jalouqa, K. (2015). Amman, from Village to Metropolis. Transformation of the urban character of Arab Cities since the late last century, 23, 23.

- Gharaibeh, A. A., Al. Zu’bi, E. A. M., & Abuhassan, L. B. (2019). Amman (City of Waters); Policy, land use, and character changes. Land, 8(12), 195.

- Pilder, A. D. (2011). Urbanization and identity: The building of Amman in the twentieth century (Master's thesis, Miami University).

- Aldabbas, A. H. M., & Atiyat, A. D. I. (2016). The impact of population migrations in contemporary Amman city architecture. Arts and Design Stud, 49, 66-75.

- Aljafari, M. (2014). Emerging public spaces in the City of Amman, Jordan: An analysis of everyday life practices (Doctoral dissertation, Universitätsbibliothek Dortmund).

- Alnsour, J. A. (2016). Managing urban growth in the city of Amman, Jordan. Cities, 50, 93-99.

- Shamout, S. , Boarin, P., & Wilkinson, S. (2021). The shift from sustainability to resilience as a driver for policy change: A policy analysis for more resilient and sustainable cities in Jordan. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 25, 285-298.

- Sharaf, F. M.(2023). Assessment of Urban Sustainability—The Case of Amman City in Jordan. Sustainability, 15(7), 5875.

- Sharaf, F. M., Çinar, H. S., & Irmeili, G. A. (2023). Quality Evaluation of Public Pedestrian Spaces: The Case of Abdali Development in Amman City, Jordan. Civil Engineering and Architecture, 11(5).

- Daher, R. F. (2008). Amman: Disguised genealogy and recent urban restructuring and neoliberal threats. In The Evolving Arab City (pp. 51-82). Routledge.

- Al Rabady, R., & Abu-Khafajah, S. (2015). ‘Send in the clown’: Re-inventing Jordan’s downtowns in space and time, case of Amman. Urban Design International, 20, 1-11.

- Kamal, O. (2020). Temporary space in Amman: a co-creation of everyday activism and state flexibility (Doctoral dissertation, Newcastle University).

- Tawakkol, L. (2023). Capitalizing on crises: the EBRD, Jordanian state and joint infrastructure fixes. Review of International Political Economy, 1-25.

- Zeadat, Z. F. (2018). A critical institutionalist analysis of youth participation in Jordan's spatial planning the case of Amman 2025 (Doctoral dissertation, Heriot-Watt University).

- Radaideh, M. (2023). Environment Ministry launches 2023-2025 strategy. Jordan Times. Retrieved from https://www.jordantimes.com (Jordan Times).

- City of Amman. (2019). Amman Resilience Strategy. Resilient Cities Network. Retrieved from https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/downloadable_resources/Network/Amman-Resilience-Strategy-English.pdf.

- Twayej, H., & Al-Nasrawy, A. (2023, April). The decentralization and its impact on achieving sustainable development goals-A case study about Najaf governorate office. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 2776, No. 1). AIP Publishing.

- Municipalities are instrumental in addressing local development challenges and delivering essential services to citizens.

- Sibanda, M., Maleka, M., & Khalo, T. (2020). Dissecting the Role of Good Governance in Enhancing Service Delivery: A Case of Mnquma Municipality. Academy of Strategic Management Journal.

- Zeadat, Z. F. (2023). Strategies toward Greater Youth Participation in Jordan’s Urban Policymaking. Journal of Sustainable Real Estate, 15(1), 2204534.

- Ladan, M. T. (2018). Achieving sustainable development goals through effective domestic laws and policies on environment and climate change. Envtl. Pol'y & L., 48, 42.

- Meuleman, L. (2018). Metagovernance for sustainability: A framework for implementing the sustainable development goals. Routledge.

- Caiado, R. G. G., Leal Filho, W., Quelhas, O. L. G., de Mattos Nascimento, D. L., & Ávila, L. V. (2018). A literature-based review on potentials and constraints in the implementation of the sustainable development goals. Journal of cleaner production, 198, 1276-1288.

- Reddy, P. S. (2016). Localising the sustainable development goals (SDGs): the role of local government in context.

- Glass, L. M., & Newig, J. (2019). Governance for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: How important are participation, policy coherence, reflexivity, adaptation and democratic institutions?. Earth System Governance, 2, 100031.

- Ricciardelli, A. (2023). Governance, local communities, and citizens participation. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance (pp. 5977-5990). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Zhang, X. Q. (2016). The trends, promises and challenges of urbanisation in the world. Habitat international, 54, 241-252.

- Wells, E. C., Lehigh, G. R., & Vidmar, A. M. (2020). Stakeholder engagement for sustainable communities. The Palgrave handbook of global sustainability, 1-13.

- Ansell, C., Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2022). The key role of local governance in achieving the SDGs. In Co-creation for sustainability: the UN SDGs and the power of local partnership (pp. 9-22). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Glass, L. M., & Newig, J. (2019). Governance for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: How important are participation, policy coherence, reflexivity, adaptation and democratic institutions?. Earth System Governance, 2, 100031.

- Meadowcroft, J. (2004). Participation and sustainable development: modes of citizen, community and organisational involvement. Governance for sustainable development: The challenge of adapting form to function, 162-190.

- Archer, D. (2018). Community-led processes for inclusive urban development. In Routledge handbook of urbanization in Southeast Asia (pp. 459-468). Routledge.

- Szetey, K., Moallemi, E. A., Ashton, E., Butcher, M., Sprunt, B., & Bryan, B. A. (2021). Participatory planning for local sustainability guided by the Sustainable Development Goals. Ecology & Society, 26(3).

- McCollum, D., Gomez Echeverri, L., Riahi, K., & Parkinson, S. (2017). SDG7: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all. In D. J. Griggs, M. Nilsson, A.-S. Stevance, & D. McCollum (Eds.), A guide to SDG interactions: from science to implementation (pp. 127-173). International Council for Science, Paris. https://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/14621. [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, E., & Sriwannawit, P. (2015). Barriers to the adoption of photovoltaic systems: The state of the art. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 49, 60-66.

- Chapin, F. S., Matson, P. A., Mooney, H. A., & Vitousek, P. M. (2002). Principles of terrestrial ecosystem ecology.

- Foley, J. A., DeFries, R., Asner, G. P., Barford, C., Bonan, G., Carpenter, S. R., ... & Snyder, P. K. (2005). Global consequences of land use. science, 309(5734), 570-574.

- Foley, J. A., Ramankutty, N., Brauman, K. A., Cassidy, E. S., Gerber, J. S., Johnston, M., ... & Zaks, D. P. (2011). Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature, 478(7369), 337-342.

- Albrechts, L. (2004). Strategic (spatial) planning reexamined. Environment and Planning B: Planning and design, 31(5), 743-758.

- Wolfram, M., Hölscher, K., & Jansen, D. (2019). Perspectives on urban transformation research: transformations in, of, and by cities. Urban Transformations. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y. (2020). Urban flooding mitigation techniques: A systematic review and future studies. Water, 12(12), 3579.

- Al-Noaimi, M. A. (2020). SDG goal 6 monitoring in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Desalination and Water Treatment, 176, 406-427.

- Al-Jayyousi, O. R. (2003). Greywater reuse: towards sustainable water management. Desalination, 156(1-3), 181-192.

- Shanableh, A., Khalil, M. A., Abdallah, M., Darwish, N., Tayara, A., Mustafa, A., ... & Al Bardan, M. (2021). Assessment and reform of greywater reuse policies and practice: a case study from Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. Water Policy, 23(2), 376-396.

- Christova-Boal, D., Eden, R. E., & McFarlane, S. (1996). An investigation into greywater reuse for urban residential properties. Desalination, 106(1-3), 391-397.

- Chen, L., Chen, Z., Liu, Y., Lichtfouse, E., Jiang, Y., Hua, J., ... & Yap, P. S. (2024). Benefits and limitations of recycled water systems in the building sector: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 22(2), 785-814.

- Khademi, H., Gabarrón, M., Abbaspour, A., Martínez-Martínez, S., Faz, A., & Acosta, J. A. (2019). Environmental impact assessment of industrial activities on heavy metals distribution in street dust and soil. Chemosphere, 217, 695-705.

- Joseph, K., Eslamian, S., Ostad-Ali-Askari, K., Nekooei, M., Talebmorad, H., & Hasantabar-Amiri, A. (2019). Environmental Impact Assessment as a tool for sustainable development. Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education, 588-596.

- NEP. (2005). Environmental Impact Assessment and Strategic Environmental Assessment: Towards an Integrated Approach. United Nations Environment Programme. Retrieved from https://www.unep.org/resources/report/environmental-impact-assessment-and-strategic-environmental-assessment-towards.

- Vujovic, S., Haddad, B., Karaky, H., Sebaibi, N., & Boutouil, M. (2021). Urban heat island: Causes, consequences, and mitigation measures with emphasis on reflective and permeable pavements. CivilEng, 2(2), 459-484.

- Akpınar, M. V., & Sevin, S. (2018). Urban heat island effects of concrete road and asphalt pavement roads. The Role of Exergy in Energy and the Environment, 51-59.

- Zhao, H., He, H., Wang, J., Bai, C., & Zhang, C. (2018). Vegetation restoration and its environmental effects on the Loess Plateau. Sustainability, 10(12), 4676.

- Zeadat, Z. F. (2022). Urban green infrastructure in Jordan: A perceptive of hurdles and challenges. Journal of Sustainable Real Estate, 14(1), 21-41.

- Munaro, M. R., & Tavares, S. F. (2021). Materials passport's review: challenges and opportunities toward a circular economy building sector. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 11(4), 767-782.

- Hoosain, M. S., Paul, B. S., Raza, S. M., & Ramakrishna, S. (2021). Material passports and circular economy. An introduction to circular economy, 131-158.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).