Submitted:

25 August 2024

Posted:

26 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

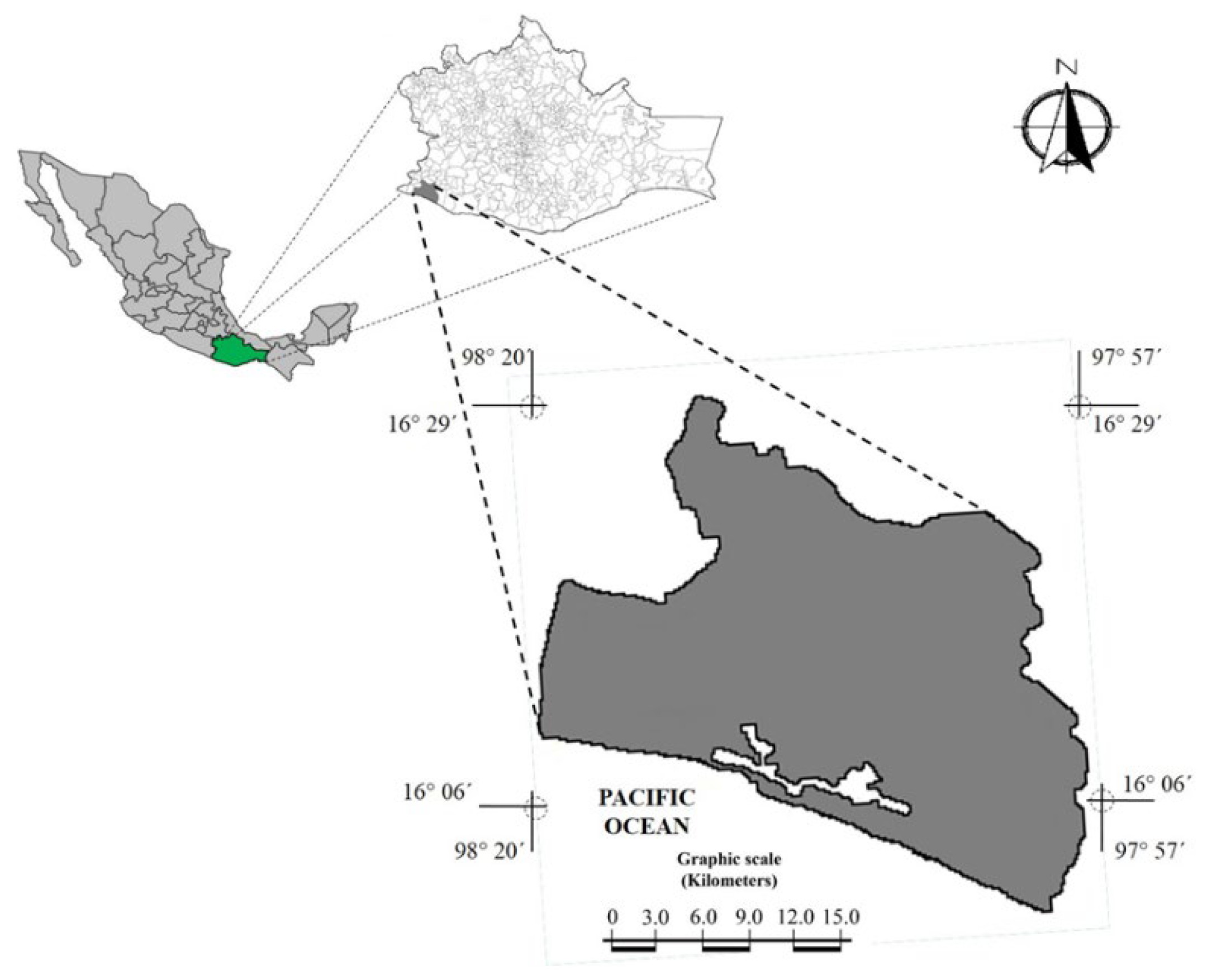

2.1. Location and Characteristics of the Study Area

2.2. Sampling and Information Gathering

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of the Social Actors

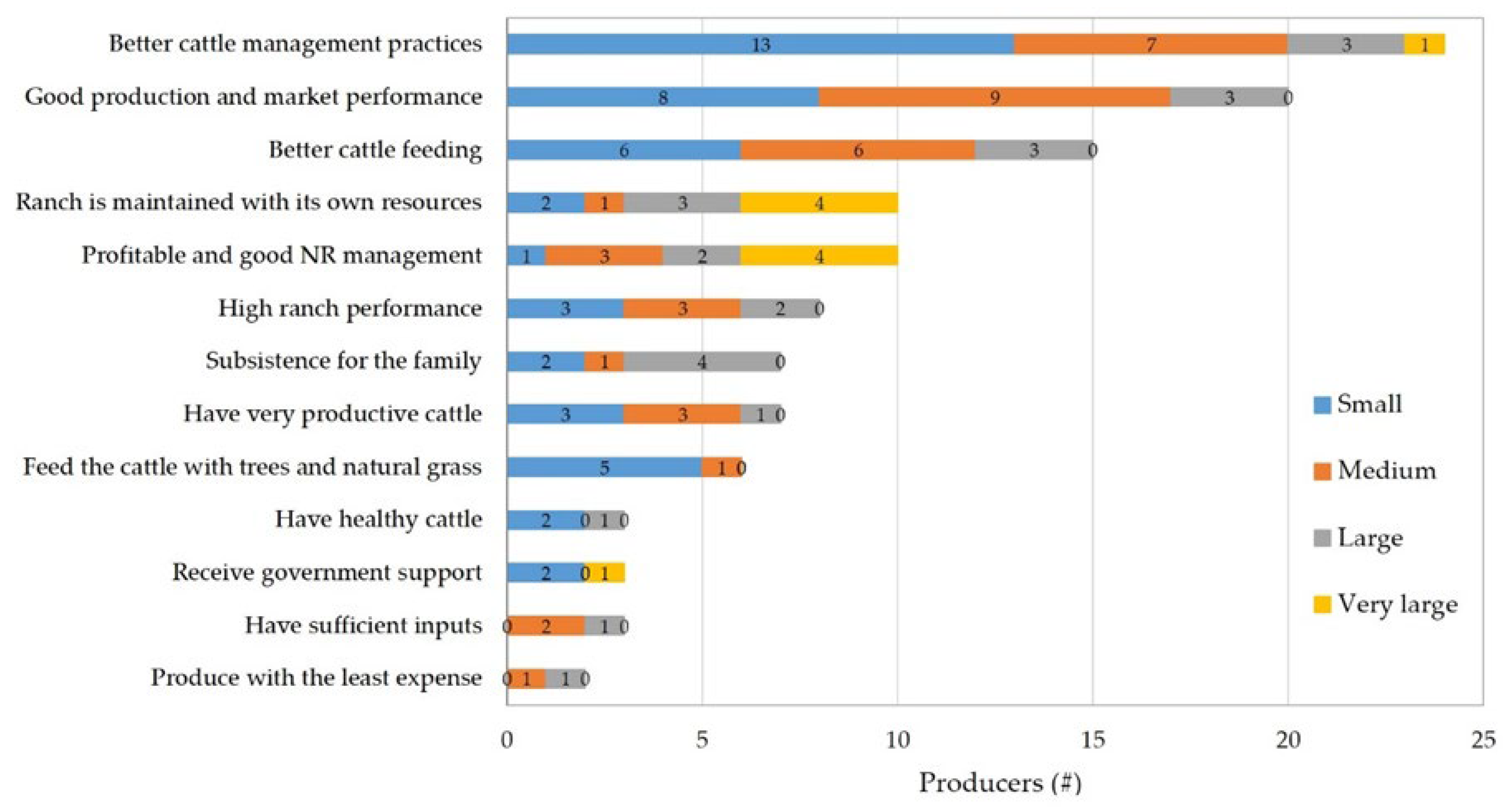

3.2. Perception of Sustainable Cattle Ranching (Idea)

- “That the farmer can be self-sufficient with better feeding practices”;

- “Milk the cows, make the cheese, sell it, take the meat. Everything will be alright with the cattle if you give them their vaccines and deworm them”;

- “Manage the cattle so that they do not damage the trees, and do not- use up all the pasture”;

- “Produce good quality food with the least possible use of antibiotics and pesticides, and use appropriate techniques to conserve the soil”;

- “Give cattle tree seeds that have vitamins”;

- “That you benefit, that it gives you the opportunity to live with dignity”;

- “Fix the well where the cattle drink water, take care of the environment and don’t burn because all the plants get burnt”;

- “Live off the cattle, from which I cover my expenses, make sure the cattle have enough to eat”;

- “That the cattle give me a little bit of food, that in the dry season I had a creek for the cattle’s water and the grass to also be able milk in the dry season”;

- “Cattle ranching that is sustained with the least transformation of nature, which does not alter nature with chemicals.

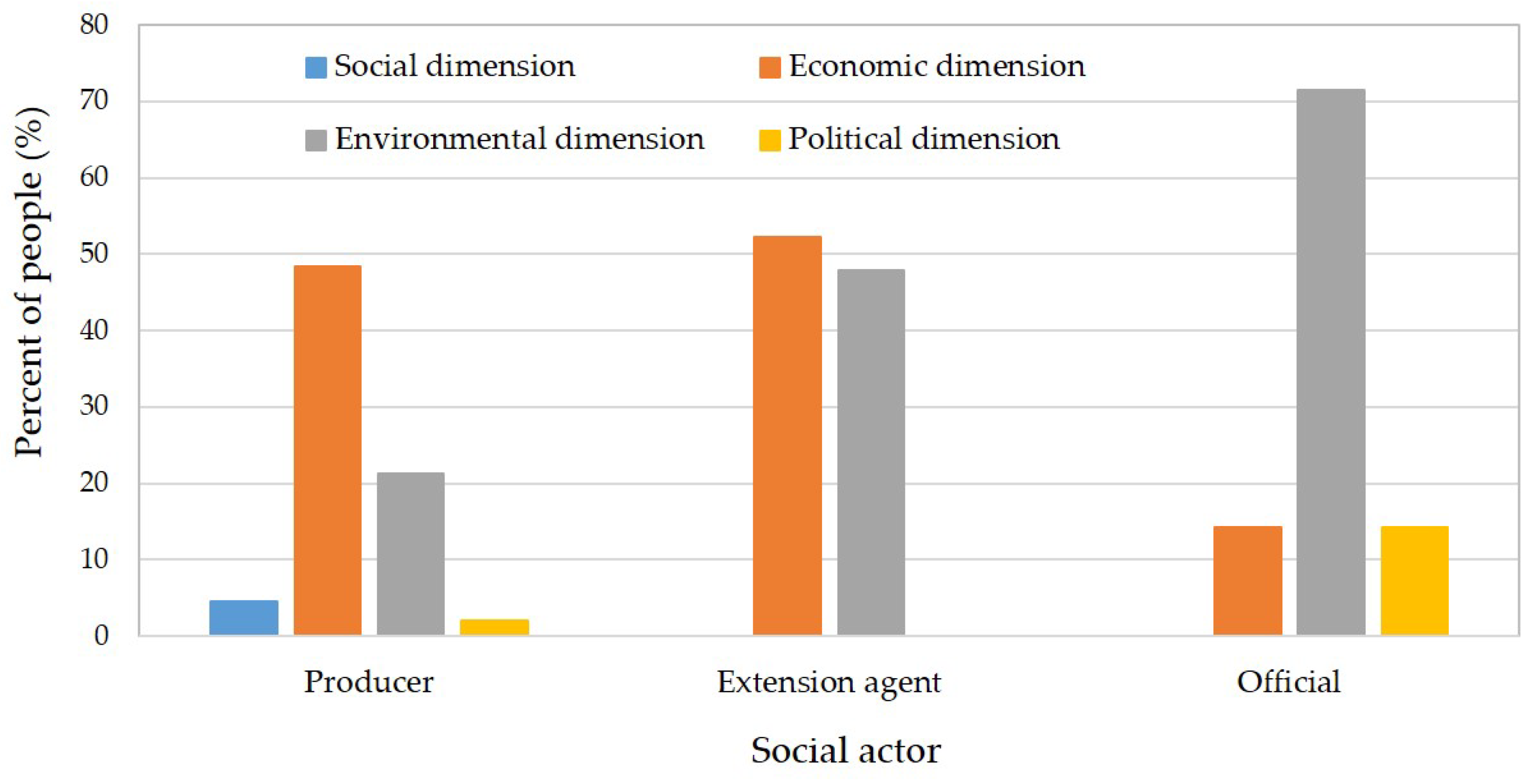

3.3. Perception of Sustainable Cattle Ranching (Assessment)

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The exchange rate used during the study was MEX 6 13.4 per US 6 1. |

References

- Singh, R.; Maiti, S.; Garai, S. Rachna Sustainable Intensification – Reaching Towards Climate Resilience Livestock Production System – A Review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2023, 23, 1037–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO World Food and Agriculture - Statistical Pocketbook 2022; FAO, 2022; ISBN 978-92-5-136931-9.

- Guevara-Hernandez, F.; Pinto, R.; Rodríguez, L.A.; Gómez, H.; Ortiz, R.; M, I.; Cruz, G. Local Perceptions of Degradation in Rangelands from a Livestock Farming Community in Chiapas, Mexico. Cuban J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Chávez-Fuentes, J.J.; Capobianco, A.; Barbušová, J.; Hutňan, M. Manure from Our Agricultural Animals: A Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis Focused on Biogas Production. Waste Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 1749–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, H.J.; Vega, A.; Martínez-Salinas, A.; Villanueva, C.; Jiménez-Trujillo, J.A.; Betanzos-Simon, J.E.; Pérez, E.; Ibrahim, M.; Sepúlveda L, C.J. The Carbon Footprint of Livestock Farms under Conventional Management and Silvopastoral Systems in Jalisco, Chiapas, and Campeche (Mexico). Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1363994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, M., V.; Bautista, V.Á.D.J.; Peláez, U.V.; Valenzuela, L.J.L.; Herrera, G.B.; Cisneros, S.P. A Comprehensive Case Study on the Sustainability of Tropical Dairy Cattle Farming in Oaxaca, Mexico. Ciênc. Rural 2023, 53, e20210026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.; Mackay, A.; Vibart, R.; Dodd, M.; McIvor, I.; McKenzie, C. Soil Carbon Stocks under Grazed Pasture and Pasture-Tree Systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 715, 136910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, S.S.; Catacutan, D.; Ajayi, O.C.; Sileshi, G.W.; Nieuwenhuis, M. The Role of Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions in the Uptake of Agricultural and Agroforestry Innovations among Smallholder Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2015, 13, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidano, A.; Gates, M.C.; Enticott, G. Farmers’ Decision Making on Livestock Trading Practices: Cowshed Culture and Behavioral Triggers Amongst New Zealand Dairy Farmers. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. The Significance and Ethics of Digital Livestock Farming. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 488–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Moheno, M.; Aide, T.M. Beyond Deforestation: Land Cover Transitions in Mexico. Agric. Syst. 2020, 178, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Alvarado, F.; Green, R.E.; Manica, A.; Phalan, B.; Balmford, A. Land-use Strategies to Balance Livestock Production, Biodiversity Conservation and Carbon Storage in Yucatán, Mexico. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 5260–5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Špirić, J.; Ramírez, M.I. Silvopastoral Systems in Local Livestock Landscapes in Hopelchén, Southern Mexico. Agrofor. Syst. 2024, 98, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Martínez, Y.; Espinosa-García, J.A.; Herrera-Haro, J.G.; Martínez-Castañeda, F.E.; Vaquera-Huerta, H.; Estrada-Drouaillet, B.; Granados-Rivera, L.D. Óptimos Técnicos Para La Producción de Leche y Carne En El Sistema Bovino de Doble Propósito Del Trópico Mexicano. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2019, 10, 933–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Reyes, V.; Loaiza, A.; Gutiérrez, O.; Buendía, G.; Rosales-Nieto, C. Typology of production units and livestock technologies for adaptation to drought in Sinaloa, Mexico. Rev. Fac. Agron. Univ. Zulia 2024, 41, e244106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos Utrera, Á.; Villagómez Amezcua Manjarrez, E.; Zárate Martínez, J.P.; Calderón Robles, R.C.; Vega Murillo, V.E. Análisis Reproductivo de Vacas Suizo Pardo x Cebú y Simmental x Cebú En Condiciones Tropicales. Rev. MVZ Córdoba 2019, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, J.; Perea, J.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Espinosa-García, J.A.; Mujica, P.T.; Feijoo, M.; Barba, C.; García, A. Structural and Technological Characterization of Tropical Smallholder Farms of Dual-Purpose Cattle in Mexico. Animals 2020, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel-Molina, O.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Barba, C.; Rangel, J.; García, A. Does Gender Impact Technology Adoption in Dual-Purpose Cattle in Mexico? Animals 2022, 12, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Márquez, I.; Toledo, V.M. Sustainability Science: A Paradigm in Crisis? Sustainability 2020, 12, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godde, C.M.; De Boer, I.J.M.; Ermgassen, E.Z.; Herrero, M.; Van Middelaar, C.E.; Muller, A.; Röös, E.; Schader, C.; Smith, P.; Van Zanten, H.H.E.; et al. Soil Carbon Sequestration in Grazing Systems: Managing Expectations. Clim. Change 2020, 161, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Saguilán, P.; Gallardo-López, F.; López-Ortíz, S.; Ruiz Rosado, O.; Herrera-Haro, J.G.; Hernández-Castro, E. Current Epistemological Perceptions of Sustainability and Its Application in the Study and Practice of Cattle Production: A Review. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2015, 39, 885–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebratu, D. Sustainability and Sustainable Development. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1998, 18, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.W. Is Agricultural Sustainability a Useful Concept? Agric. Syst. 1996, 50, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Cassman, K.G.; Matson, P.A.; Naylor, R.; Polasky, S. Agricultural Sustainability and Intensive Production Practices. Nature 2002, 418, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavra, M. Sustainability of Animal Production Systems: An Ecological Perspective. J. Anim. Sci. 1996, 74, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, B.K.; Mutegi, J.K.; Wironen, M.B.; Wood, S.A.; Peters, M.; Nyawira, S.S.; Misiko, M.T.; Dutta, S.K.; Zingore, S.; Oberthür, T.; et al. Livestock Solutions to Regenerate Soils and Landscapes for Sustainable Agri-Food Systems Transformation in Africa. Outlook Agric. 2023, 52, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitschmidt, R.K.; Short, R.E.; Grings, E.E. Ecosystems, Sustainability, and Animal Agriculture. J. Anim. Sci. 1996, 74, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltjen, J.W.; Beckett, J.L. Role of Ruminant Livestock in Sustainable Agricultural Systems. J. Anim. Sci. 1996, 74, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, S.; Dollinger, J. Silvopasture: A Sustainable Livestock Production System. Agrofor. Syst. 2019, 93, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovarelli, D.; Bacenetti, J.; Guarino, M. A Review on Dairy Cattle Farming: Is Precision Livestock Farming the Compromise for an Environmental, Economic and Social Sustainable Production? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, E.; Linnerud, K.; Banister, D. Sustainable Development: Our Common Future Revisited. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 26, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera-Méndez, P.; Molera, L.; Semitiel-García, M. The Role of Social Learning in Fostering Farmers’ pro-Environmental Values and Intentions. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 46, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.C.; Leviston, Z. Predicting Pro-Environmental Agricultural Practices: The Social, Psychological and Contextual Influences on Land Management. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 34, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Verbeke, W.; Van Poucke, E.; Tuyttens, F.A.M. Do Citizens and Farmers Interpret the Concept of Farm Animal Welfare Differently? Livest. Sci. 2008, 116, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marroquín-Pugas, O.; Montero-Solís, F.M.; Luis-Santiago, M.Y.; Cruz-Gallegos, E.; Cisneros-Saguilán, P. Limitantes y Oportunidades Para Implementar Sistemas Silvopastoriles En La Costa de Oaxaca, México. Rev. Mex. Agroecosistemas 2022, 9, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI Anuario estadístico y geográfico de Oaxaca 2016; 1a ed.; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geográfica: Aguascalientes, México, 2016; ISBN 978-607-739-966-7.

- INEGI Panorama sociodemográfico de Oaxaca - Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020; 1a ed.; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Aguascalientes, México, 2021.

- SIAP-SAGARPA Oaxaca Infografía Agroalimentaria 2016; 1a ed.; Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria: Ciudad de México, México, 2016.

- INEGI Principales resultados de la encuesta intercensal 2015; 1a ed.; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Aguascalientes, México, 2015.

- SIAP-SADER Sistema de Información Agroalimentaria de Consulta 2024.

- Martínez-Castro, C.J.; Ríos-Castillo, M.; Castillo-Leal, M.; Jiménez-Castañeda, J.C.; Cotera-Rivera, J. Sustentabilidad de Agroecosistemas En Regiones Tropicales de México. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosystems 2015, 18, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- SIAP-SADER Oaxaca, Infografía Agroalimentaria 2023; Infografías Agroalimentarias; 2023rd ed.; Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria: Ciudad de México, México, 2023.

- Arrieta-González, A.; Hernández-Beltrán, A.; Barrientos-Morales, M.; Martínez-Herrera, D.I.; Cervantes-Acosta, P.; Rodríguez-Andrade, A.; Dominguez-Mancera, B. Caracterización y Tipificación Tecnológica Del Sistema de Bovinos Doble Propósito de La Huasteca Veracruzana México. Rev. MVZ Córdoba 2022, 27, e2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIAP-SADER Sistema de Información Agroalimentaria de Consulta 2020.

- Scheaffer, R.L.; Mendenhall, W.; Lyman Ott, R. Elementos de Muestreo; 6a ed.; Ediciones Paraninfo, SA: España, 2007; ISBN 84-9732-493-5.

- Noy, C. Sampling Knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogaard, B.K.; Oosting, S.J.; Bock, B.B. Elements of Societal Perception of Farm Animal Welfare: A Quantitative Study in The Netherlands. Livest. Sci. 2006, 104, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, I.; Nicholson-Cole, S.; Whitmarsh, L. Barriers Perceived to Engaging with Climate Change among the UK Public and Their Policy Implications. Glob. Environ. Change 2007, 17, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, A.; Walker, S.; Cooper, T. Beyond Abundance: Self-Interest Motives for Sustainable Consumption in Relation to Product Perception and Preferences. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1431–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolisca, F.; McDaniel, J.M.; Teeter, L.D. Farmers’ Perceptions towards Forests: A Case Study from Haiti. For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, G.E.; Fassola, H.E.; Pachas, A.N.; Colcombet, L.; Lacorte, S.M.; Pérez, O.; Renkow, M.; Warren, S.T.; Cubbage, F.W. Perceptions of Silvopasture Systems among Adopters in Northeast Argentina. Agric. Syst. 2012, 105, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, M.; Therond, O. Livestock System Sustainability and Resilience in Intensive Production Zones: Which Form of Ecological Modernization? Reg. Environ. Change 2015, 15, 1651–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogaard, B.K.; Oosting, S.J.; Bock, B.B.; Wiskerke, J.S.C. The Sociocultural Sustainability of Livestock Farming: An Inquiry into Social Perceptions of Dairy Farming. Animal 2011, 5, 1458–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statsoft Inc Statistica 2003.

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgueitio, E. Incentivos Para Los Sistemas Silvopastoriles En América Latina. Av. En Investig. Agropecu. 2009, 13, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Petrzelka, P.; Korsching, P.F.; Malia, J.E. Farmers’ Attitudes and Behavior toward Sustainable Agriculture. J. Environ. Educ. 1996, 28, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.; Abramson, P.R. Measuring Postmaterialism. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1999, 93, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaefer, F.; Roper, J.; Sinha, P. A Software-Assisted Qualitative Content Analysis of News Articles: Example and Reflections. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2015; 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leos-Rodríguez, J.A.; Serrano-Páez, A.; Salas-González, J.M.; Ramírez-Moreno, P.P.; Sagarnaga-Villegas, M. Caracterización de Ganaderos y Unidades de Producción Pecuaria Beneficiarios Del Programa de Estímulos a La Productividad Ganadera (PROGAN) En México. Agric. Soc. Desarro. 2008, 5, 213–230. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI Anuario estadístico y geográfico de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos 2013; Anuario estadístico; 1a ed.; Instituo Nacional de Estadistica y Geografía: Aguascalientes, México, 2014.

- Mendez Cortes, V.; Mora Flores, J.S.; García Salazar, J.A.; Hernández Mendo, O.; García Mata, R.; García Sánchez, R.C. Tipología de Productores de Ganado Bovino En La Zona Norte de Veracruz. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosystems 2019, 22, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuquirima, R.D.; García, S.M.E.; Hidalgo, V.Y. Componentes Del Sistema de Producción de Bovinos Doble Propósito En Los Cantones Nangaritza y Palanda, Provincia Zamora Chinchipe, Ecuador. Rev. Investig. Vet. Perú 2023, 34, e23850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.G.M.; Dorward, P.; Rehman, T. Farm and Socio-Economic Characteristics of Smallholder Milk Producers and Their Influence on Technology Adoption in Central Mexico. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2012, 44, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarrán-Portillo, B.; García-Martínez, A.; Ortiz-Rodea, A.; Rojo-Rubio, R.; Vázquez-Armijo, J.F.; Arriaga-Jordán, C.M. Socioeconomic and Productive Characteristics of Dual Purpose Farms Based on Agrosilvopastoral Systems in Subtropical Highlands of Central Mexico. Agrofor. Syst. 2019, 93, 1939–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahyari, M.S.; Chizari, M.; Homaee, M. Perceptions of Iranian Agricultural Extension Professionals toward Sustainable Agriculture Concepts. J. Agric. Soc. Sci. 2008, 4, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Landini, F.; Bianqui, V. Socio-Demographic Profile of Different Samples of Latin American Rural Extensionists. Ciênc. Rural 2014, 44, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, J.I.; Eastwood, C.R.; Garcia, S.C.; Lyons, N.A. Dairy Farmers with Larger Herd Sizes Adopt More Precision Dairy Technologies. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 5466–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanin, A.; Dal Magro, C.B.; Kleinibing Bugalho, D.; Morlin, F.; Afonso, P.; Sztando, A. Driving Sustainability in Dairy Farming from a TBL Perspective: Insights from a Case Study in the West Region of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borroto, Pérez M.; Rodríguez, P. L.; Ramírez, A.R.; Vázquez, A.B.L. Percepción Ambiental En Dos Comunidades Cubanas. M Rev. Electrónica Medioambiente 2011, NA-NA.

- Orefice, J.; Smith, R.G.; Carroll, J.; Asbjornsen, H.; Howard, T. Forage Productivity and Profitability in Newly-Established Open Pasture, Silvopasture, and Thinned Forest Production Systems. Agrofor. Syst. 2019, 93, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Botero, I.C.; Villegas, D.M.; Montoya, A.; Mazabel, J.; Bastidas, M.; Ruden, A.; Gaviria, H.; Peláez, J.D.; Chará, J.; Murgueitio, E.; et al. Effect of a Silvopastoral System with Leucaena Diversifolia on Enteric Methane Emissions, Animal Performance, and Meat Fatty Acid Profile of Beef Steers. Agrofor. Syst. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia Salazar, S.S.; Piñeiro Vázquez, A.T.; Molina Botero, I.C.; Lazos Balbuena, F.J.; Uuh Narváez, J.J.; Segura Campos, M.R.; Ramírez Avilés, L.; Solorio Sánchez, F.J.; Ku Vera, J.C. Potential of Samanea Saman Pod Meal for Enteric Methane Mitigation in Crossbred Heifers Fed Low-Quality Tropical Grass. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 258, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.M.; Bentrup, G.; Kellerman, T.; MacFarland, K.; Straight, R.; Ameyaw, Lord; Stein, S. Silvopasture in the USA: A Systematic Review of Natural Resource Professional and Producer-Reported Benefits, Challenges, and Management Activities. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 326, 107818. [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, D.; Fioravanzi, M.; Donati, M. Farmer’s Motivation to Adopt Sustainable Agricultural Practices. Bio-Based Appl. Econ. 2015, 125-147 Pages. [CrossRef]

- Silici, L.; Bias, C.; Cavane, E. Sustainable Agriculture for Small-Scale Farmers in Mozambique. Int. Inst. Environ. Dev. Lond. UK 2015.

| Unit of analysis | Description |

|---|---|

| Producer | Producer of milk, meat or dual-purpose cattle |

| Extension agent | Extension technician (Veterinarian or Zootechnician Agronomist) who advises farmers in a private or governmental way. |

| Official | Executives of institutions related to cattle farming in the study area, for example SAGARPA, Rural Finance Authority, FIRA, Regional Social Development Module, ICAPET, UGRCO and AGL. |

| Stratum | No. de Producers |

Mean (No. of cattle) |

Standard deviation |

ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small (1 – 20) | 704 | 9.86 | 5.21 | 66 |

| Medium (21– 40) | 228 | 29.39 | 5.65 | 23 |

| Large (41– 100) | 130 | 66.49 | 18.32 | 43 |

| Very large (> 100) | 22 | 154.16 | 57.88 | 23 |

| Total/Average | 1084 | 64.97 | 21.76 | 155 |

| Dimension | Positive perception items | P | E | O |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | ||

| SCR meat and milk are healthier | 98.7 | 95.7 | 100 | |

| Social | Trees in paddocks provide shade and a pleasant climate to the cattle and producer |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| A sustainable ranch is more beautiful and orderly in its landscape |

98.1 |

87.0 |

100 |

|

| SCR is more profitable than conventional cattle ranching |

77.4 |

65.2 |

85.7 |

|

| Economic | Trees in paddocks provide fruits, forage, firewood and posts |

99.4 |

91.3 |

85.7 |

| SCR provides a diversity of income on the ranch | 87.1 | 82.6 | 100 | |

| Trees help control soil erosion and protect rivers | 98.1 | 100 | 85.7 | |

| Trees help clean the air | 97.4 | 100 | 100 | |

| Environmental | In SCR, wild animals and plants are conserved and increased | 92.9 |

95.7 |

100 |

| Dimension | Negative perception items | P | E | O |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | ||

| SCR requires more organization and training | 96.8 | 78.3 | 85.7 | |

| Social | Few technicians trained in SCR | 81.3 | 52.2 | 85.7 |

| In SCR, cattle management in more difficult | 33.5 | 30.4 | 57.1 | |

| SCR requires high capital investment | 73.5 | 13.0 | 28.6 | |

| Economic | Trees in paddocks limit the growth of the grass | 66.5 | 30.4 | 42.9 |

| With many trees on the ranch, people steal firewood fruits and wood | 76.1 | 65.2 | 28.6 | |

| With more trees in paddocks there are more pests and diseases on the ranch | 29.0 | 4.3 | 0.0 | |

| Environmental | With more trees in paddocks more snakes abound | 53.5 | 34.8 | 14.3 |

| Dry branches and trees fall and hurt the cattle | 59.4 | 34.8 | 28.6 |

| Net perception index |

Producer (n = 155) |

Extension agent (n = 23) |

Official (n = 7) |

|||||||||

| x̄ | SD | Min | Max | x̄ | SD | Min | Max | x̄ | SD | Min | Max | |

| Social* | 0.9b | 0.7 | -1.0 | 3.0 | 1.2a | 1.0 | -1.0 | 3.0 | 0.7b | 0.8 | 0.0 | 2.0 |

| Economic** | 0.5b | 1.1 | -2.0 | 3.0 | 1.3a | 1.3 | -1.0 | 3.0 | 1.7a | 1.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 |

| Environmental** | 1.5b | 1.1 | -2.0 | 3.0 | 2.2a | 1.0 | -1.0 | 3.0 | 2.4a | 0.5 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| ONPI** | 0.9b | 0.7 | -1.0 | 3.0 | 1.6a | 0.9 | -0.7 | 2.7 | 1.6a | 0.5 | 0.7 | 2.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).